“Stone Mattress” is a masterful short story written by Margaret Atwood, published in The New Yorker in 2011. You’ll also find this story in the Nine Wicked Tales collection.

Some years later, in 2018, author A.M. Homes discussed this story with Deborah Treisman via the New Yorker Fiction podcast, noting that this is (unfortunately) a timeless story.

How many rapists must we kill until men stop raping us?

Mona Eltahawy (and implied by Margaret Atwood)

HUMANS HAVE ALWAYS KILLED

Sophie Lewis, author of Full Surrogacy Now, argues that pro-choice feminists should accept that abortion is a form of killing rather than fighting against that. Once that aspect is acknowledged, she argues, forced-birthers will be left to make clear the next part of their argument: That pregnant people (mostly women) are being forced into labour. As part of that argument, she makes the following observation:

We humans do kill, when necessary: Victims of assault sometimes kill in self-defense, targets of persecution sometimes kill for justice—or just to reduce the number of their persecutors—and the colonized sometimes kill for liberation. Mothers living in unspeakable conditions (including chattel slavery) have been documented to kill their children as an act of mercy. Of course, these examples are instances of necessary violence, generated by the conditions for which we struggle to render extinct.

Sophie Lewis at The Nation

SETTING OF “STONE MATTRESS”

No matter when you first read “Stone Mattress” there will be a report circulating in the media about power, abuse and sexual assault, followed by commentary about all the things women and girls must do to stop men from assaulting women and girls (to say nothing of men invisibly assaulting other men).

Here’s today’s example (among others):

The Defence Department has told The Canberra Times that General Angus Campbell believed it was important for “young attractive people” to be aware of risk factors such as alcohol and being out and alone after midnight.

Defence chief General Angus Campbell criticised for warning young cadets against being out late to avoid sexual predators

On the day I first read “Stone Mattress,” Australia was waiting to learn which of our male sitting MPs was about to appear with his defamation lawyer to the nation and insist that no, he is not the perpetrator of a violent “historical” rape. (The word “historical” is standard terminology, though for victims, trauma does not live in the past.)

I often think of the time Egyptian-American feminist journalist Mona Eltahawy was invited onto the panel of a popular news talk show here in Australia. After airing this episode, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) received 250 complaints about the November 4, 2019 episode of Q&A, and removed the segment from all of the national broadcaster’s platforms.

“How many rapists must we kill until men stop raping us?” Eltahawy asked. Complainants considered this incitement of violence, heavily muddied with tone policing; Eltahawy uses taboo language mindfully and for political purpose. Many Australians don’t feel warm and fuzzy hearing a woman of colour using curse words on national television.

Eltahawy clarified afterwards, “I’m saying violence has been owned by the state, given by the stage, allowed to continue unchecked mostly by men and especially by privileged men. So how long do I have to wait to be safe?”

In effect, a woman talking about imaginary, hypothetical violence exacted against hypothetical men is more shocking to (enough) Australians than the real and present reality of men killing women.

When I read “Stone Mattress”, I realised Margaret Atwood conveys in this short story what Mona Eltahawy was saying on a panel. “How many rapists must we kill until men stop raping us?” the story asks.

Eltahawy was silenced; Atwood is not.

There are race issues here too, regarding who is allowed to speak in mainstream spaces and who the white patriarchy hopes to keep out. Still, this is an excellent case study into how it’s possible to explore via fiction ideas which are too often censored when presented in any other way.

PERIOD

The story takes place near time of publication (2011) but stretches back into the viewpoint character’s history as a young woman.

DURATION

The length of a holiday cruise.

LOCATION

According to Foucault, the ship is the standout example of a heterotopia, a space which runs parallel to the rest of human existence. Heterotopia is a ‘real world utopia’. A utopia has no real place. A utopia is a ‘perfect version’ of a real place — a society turned upside down. But heterotopias are fundamentally unreal.

There’s a well-known psychological phenomenon in which people go on holiday and do outlandish things. This is often used for comical effect in stories, or sometimes the shedding of one’s usual, repressed self requires the heterotopic setting of a holiday for the character to shed their mask and for that ‘real’ self to become permanent. (Shirley Valentine is a good example.)

ARENA

This story has the structure of a road trip, though the vehicle is a ship rather than a car or a van. The Arctic trip is expanded via flashbacks into Verna’s past. The cruise ship passengers stop off at various points along the way.

Notice how shipping metaphors affect the way Verna sees the world even before she embarks:

Little by little she jettisoned the crushed image of Bob that she still carried like a dried flower—incredibly!—next to her heart.

“Stone Mattress”

To ‘jettison’ is to throw or drop (something) from an aircraft or ship.

If you’re writing a work of fiction and you’re keen to flesh out your symbol web in a cohesive and interesting way, I highly recommend making use of the advanced features in the free online dictionary Onelook.

MANMADE SPACES

The cruise ship

NATURAL SETTINGS

The Arctic. This setting will return Verna to the horrible inciting incident of her adolescent life.

She has a picture of herself limping along the icy roadside with her bare feet stuck in her dyed-to-match ice-blue heels, dizzy and raw and shivering and—a further ridiculous humiliation—hiccupping.

“Stone Mattress”

WEATHER

There is some pathetic fallacy at work here: Verna has stone-cold resolve, hence a trip to The Arctic (the ultimate in chill weather).

The Arctic suits her: there’s something inherently calming in the vast cool sweeps of ice and rock and sea and sky, undisturbed by cities and highways and trees and the other distractions that clutter up the landscape to the south.

“Stone Mattress”

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The cruise, which is familiar to audiences even if we’ve never been on a cruise ourselves. We understand these to be packaged holidays where passengers expect the details of itinerary and daily living to be fully taken care of.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

In the wider world of the story, women with “historical” rape trauma have no recourse in the vast majority of cases. These assaults are avoided as topics of conversation, resulting in hermeneutical injustice of the most painful kind: People who have terrible things done unto them don’t have the words to describe it.

This state of affairs has changed over Verna’s lifetime. Today we call this ‘date rape’. Accessing the words has given Verna the power to do something with them. (We now also have a word for the arrangement Verna struck up with her first much older man: Sugaring.) When we don’t have the language to describe our experiences, this is known as hermeneutic injustice.

The power structures avenged in this story are as old as time itself, a fact underscored with the following description:

They’ll be privileged to see the world’s earliest fossilized stromatolites, clocking in at an astonishing 1.9 billion years old—before fish, before dinosaurs, before mammals—the very first preserved form of life on this planet.

“Stone Mattress”

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

A heterotopia is a place that represents society, but in a distorted way which calls to mind particular idealised aspects of the culture.

Up for discussion: Is Verna of “Stone Mattress” distorted in her thinking, or is she filled with a stone-cold, utterly logical resolve? Perhaps the distorted heterotopia of the cruise ship is precisely what allows Verna to see the ‘real’ world as it really is.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “STONE MATTRESS”

This is a story about an “unresolved moral situation, or one which is resolved unexpectedly”. Another way of saying this: The plot hinges upon a moral dilemma. Stories with strong moral dilemmas tend to be the most satisfying.

Here’s the key point about a satisfying moral dilemmas: There’s no good path. Here, doing something and not doing something are as bad for Verna as each other. Fictional moral dilemmas don’t work unless the storyteller can successfully convince an audience of that.

PARATEXT

epiTEXT

a light, comic, gothic story about a senior citizen having her revenge

Treisman

Water is patient. Dripping water wears away a stone. Remember that, my child. Remember you are half water. If you can’t go through an obstacle, go around it. Water does.

Atwood, elsewhere

THE TITLE of “Stone mattress”

Atwood refers to the stories in this collection as ‘tales’, suggesting they fit into the world of fairytale, folklore and parable. A.M. Homes would love Atwood to do her her own take on the Bible. (Treisman says this story feels like the Atwood “Samson and Delilah”.)

Atwood utilises ecological points-of-interest as motif across this short story, with the stone mattress at the centre.

Stone mattress: a fossilized cushion, formed by layer upon layer of blue-green algae building up into a mound or dome. It was this very same blue-green algae that created the oxygen they are now breathing.

I recently watched Little Fires Everywhere and noticed one sister calls the other “Jock Mattress” as an insult. Women who enjoy sex (or not) with a variety of partners have been compared to literal objects for centuries. “Town bike” is a common one I grew up with. When Atwood chooses “mattress” I suspect this is a macabre play on words as insult against women. Also:

Verna had made her own bed, and now she would have to lie in it.

Verna’s mother, “Stone Mattress”

When ‘mattress’ is paired with ‘stone’ we have an ironic and brand new concept.

As symbol and motif, stone is multivalent. There are literal rocks in this story, then there is a “stone cold bitch”. What might turn a woman into a “stone cold bitch”, anyway? That is the central question this story explores.

SHORTCOMING

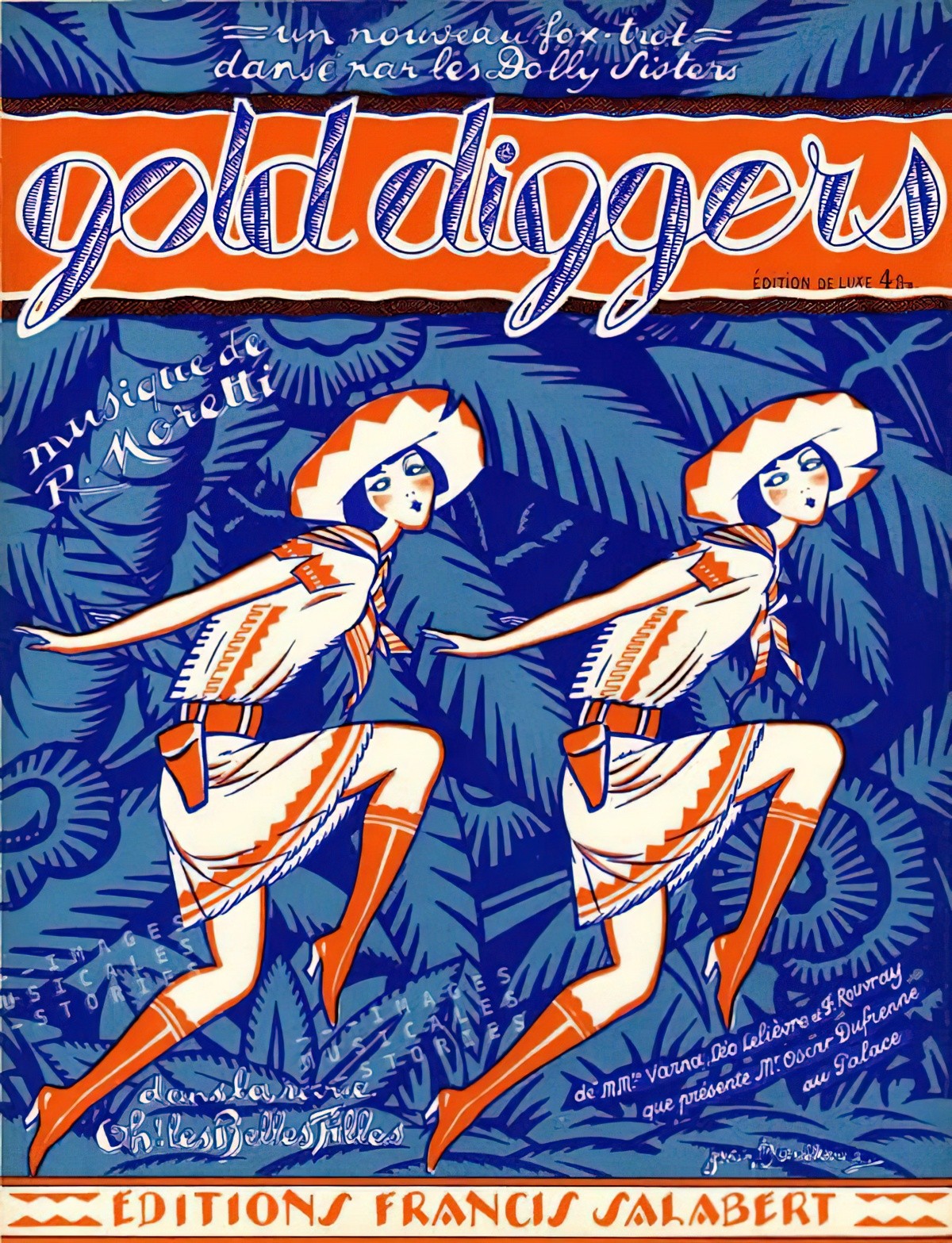

As the story opens, I feel Margaret Atwood is painting the picture of a so-called “gold-digger”.

She doesn’t need the cash, not anymore. She’s not extravagant or greedy, she tells herself: all she ever wanted was to be protected by layer upon layer of kind, soft, insulating money, so that nobody and nothing could get close enough to harm her. Surely she has at last achieved this modest goal.

“Stone Mattress”

Why is Verna regarding these male passengers with such cold, hard logic, I wonder. Why is she summing them up according to likely health? Does her calculation include the sum or richest plus most-likely-to-die?

The following magazine cover is from 1920, when men held 99.99% of the world’s economy and women, whose best chance at comfort was to marry into it, were labelled “gold-diggers”. The image below suggests humorous intent but the best humour also speaks to deeply held fears.

Under patriarchy, the fear of the gold-digger is a specifically masculine fear: That the most important woman in a man’s life is only with him for the money. In cultures without career options, birth control, higher education or social security for women, this is a somewhat warranted fear.

Atwood being Atwood, my gold-digger expectation is subverted.

she doesn’t want much more than her due, but she doesn’t want much less, either. She likes balanced accounts.

“Stone Mattress”

Verna is not after a man for his money. Ha, nope. Verna is so much worse than the men even imagined! She’s so bad, they don’t even see her coming.

Near the climax of the story, Verna notes that “Some [stromatolites] lost their tops, like eggs in the process of hatching.” Verna herself was still in the process of hatching when she had her dignity stripped from her. This trip will be her late-life coming-of-age story.

When Verna looks at her glammed-up trickster self in the mirror she quotes a line from “Ulysses” by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Another line from that poem rings true for Atwood’s story: “‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.” This feels like an old woman doing something to disrupt the highly disagreeable status quo before she shuffles off this mortal coil.

The narrator wants us to understand these poetic allusions. Atwood tells us that Verna’s ‘third husband had been a serial quotation freak with a special penchant for Tennyson.’ So what of the line, “Come into the garden, Maud” which drives her especially mad? “Maud” is an especially purple melodrama, the epitome of romance with transferred epithets galore. This poem juxtaposes comically with Verna’s aromanticism.

Verna has amassed a collection of quirky, knowing and darkly funny aphorisms. These are not things Verna’s ideals, but observations Verna has made about how the world really works:

- Discarded wives stick like burrs.

- A sneezing man is not an attentive man.

- A piggy, gobbling woman is not a creature of mysterious allure.

- On a cruise, word of mouth spreads like the flu.

These aphorisms juxtapose against the famous, Romantic poetry of the Great (Male) Poets Verna quotes (via her poetry loving former husband e.g.

- Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.

Tennyson and Keats are men and this is significant. Atwood is saying something about how men view the world in ridiculously optimistic terms, at times convincing themselves that everything is fine. They are so easily convinced, too. The Bob easily believes that Verna is upset only because food went down the wrong way. But it’s easy to coast along with romantic-coloured glasses on when, for your whole life, things have gone the right way.

Because these men are so optimistic and besotted, they technically kill themselves.

All she’d done was give them tacit permission to satisfy every forbidden desire: to eat artery-clogging foods, to drink as much as they liked, to return to their golf games too soon.

“Stone Mattress”

DESIRE

Surface desire

At the outset Verna had not intended to kill anyone. What she had in mind was a vacation, pure and simple. Take a breather, do some inner accounting, shed worn skin.

“Stone Mattress”, opening lines

While talking about that first line, let’s talk a little about Atwood’s distinctive narration.

The opening to “Stone Mattress” may remind you of the opening to Lady Oracle (1976), a novel by Margaret Atwood which parodies Gothic romances and fairy tales:

I planned my death carefully; unlike my life, which meandered along from one thing to another, despite my feeble attempts to control it…The trick was to disappear without a trace, leaving behind me a shadow of a corpse, a shadow everyuone would mistake for solid reality. At first I thought I’d managed it.

Lady Oracle

In content they juxtapose, of course: One narrator did not intend to kill anyone, the other planned death carefully (if not life). In Gothic Forms of Feminine Fictions, Susanne Becker has this to say about Lady Oracle, and the mode of narration she describes can also apply to “Stone Mattress”:

If Atwood rewrites the gothic in Lady Oracle, she does so with an ironic double-voice that allows for self-reflexivity and an implicit critique. That this voice has firstly a profound effect on the gothic’s ‘affective form’ and transforms it into a comedy, becomes clear from the novel’s opening […] This opening initiates the ironic play with the gothic pattern. While instantly evoking one basic emotion structuring the typical gothic romance, the fear of death, it works to undercut that emotion as it installs it. The idea of death as self-constructed and -controlled performance, does not evoke threat, but rather ridicule, an effect enhanced by the concluding hint that the performance might have failed.

Gothic Forms of Feminine Fictions, Susanne Becker

This voice, utilised by Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro and others writing the ‘female neo-gothic’ has been called an ironic double voice.

Parody is one weapon against marginalisation, which is probably why woman writers have become known for making use of the ironic double voice. You’ll come across this term reading about the female neo-gothic, especially in relation to Margaret Atwood.

WHAT IS IRONIC DOUBLE VOICE?

Ironic double voice, or ironic double address, is a Postmodern technique, encouraging a Postmodern reading of a work. In ironic double address, the narrator addresses both the character(s) in the story and also the reader, highlighting the contrast between the characters’ perceptions and the reality of the story.

The effect: An ironic double voice changes a story’s tone, from sublime and dark to comic Postmodern Gothic (which is no less dark, mind you).

What, exactly, is the ‘double-ness’ in Margaret Atwood’s ‘ironic double address’? Well, the narrator might be joking, or she might not be. That’s up to you. Is this a parody of a Miss Marple story? Who knows. Is it fantasy?

This narrative mode reflects the duplicity of the main character, Verna, of course, who appears one thing (a coquettish older woman) but who is in fact someone very different (a traumatised woman with murderous thoughts). This state of behaving according to the rules of femininity (while masking one’s real feelings) is recognisable to anyone with marginalised identities. In the case of women and femme-presenting people, the expectation is that women be polite and accommodating at all times, so Atwood’s ironic double address may be especially recognisable to femmes.

Contrast Atwood’s ironic double address with a similar technique, made famous by 20th century male children’s authors (who, no coincidence, also wrote for adults, or aspired to): Mark Twain, E.B. White and A.A. Milne. All of these men ‘winked’ at their adult audiences in stories which appealed, on another level, to children.

Margaret Atwood’s ‘wink’ is not designed to go over the heads of children; instead, it will go over the heads of readers who, today, might be described as ‘not quite woke‘. In fact, he may be quite angry about this fictional woman — the fictional, hypothetical woman evoked by Mona Eltahawy when she came to Australia and asked, on national TV, “How many men do we need to kill before men stop raping us?”

Deeper desire

By the end of the story, Verna wants to exact revenge.

Deepest desire

To feel better.

People say revenge doesn’t help.

Gina Baxter, Season One, Episode Five of Your Honor, whispered into the ear of her mob boss husband after he murders the entire family of a boy she thinks killed her son.

What you did, the move you made…

it won’t bring him back,

My heart will never heal.

Do I feel better?

Absolutely.

OPPONENT

Bob is a sexual predator but Atwood diminishes him by depicting him in late middle-age as a comic archetype. In later life, Verna has reached the point where certain types of men are interchangeable to her. (Men who don’t listen, men who wilfully disregard women, men who don’t see women as equals.)

Atwood calls these men ‘Bobs’.

Note the foreshadowing:

She notes the nametags: a Fred, a Dan, a Rick, a Norm, a Bob. Another Bob, then another: there are a lot of Bobs on this trip. Several appear to be flying solo. Bob: a name once of heavy significance to her, though surely she’s rid herself of that load of luggage by now.

“Stone Mattress”

How much is this man a predator and how much is he opportunist? If this historical rape were the sort of crime that made it to court, the evidence would be stacked against him: He already imbibed the liquor, he drove Verna to another place so he would not be disturbed, and he had picked a younger victim. This is a premeditated crime. If he hadn’t found Verna, he’d have found someone else to assault.

Atwood presents Verna as victim turned victimiser. In the opening paragraph Verna ‘sheds her skin’, in comparison to a snake or some other creepy animal. In a kinder reading, encouraged by the end, Verna has transformed like a butterfly.

However, near the beginning, when Atwood’s narrator tells us, ‘It’s the solitaries who interest her, the lurkers at the fringes,’ Verna is now the predator, as she was once predated upon. We don’t yet know why these men are her prey.

This same man goes on to experience love at first sight, he remains married and enjoys a brilliant career. (We don’t hear the wife’s side.)

Verna receives no assistance from the person whose job it is to care for her most.

Verna’s mother is presented as “an Aunt Lydia character” who upholds the patriarchy by functioning as the police of reproduction. (Aunt Lydia is the older woman in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale who finds her own powerful place in the patriarchy by oppressing other women.)

a strict Presbyterian with a mouth like a vise grip, who despised poetry and was unlikely to have been influenced by anything softer than a granite wall.

“Stone Mattress”. Note how Atwood unifies her motifs across the story. Even the mother is compared to a geological feature.

When Verna is raped (or at the very least coerced into sex) as a young woman and then becomes pregnant, Verna’s mother offers no comfort. Verna is the one punished. The rest of Verna’s life would have gone much differently had the mother been sympathetic.

PLAN

Notice the masterful way in which Atwood tells us matter-of-factly what’s happening, though we can’t be sure she’s not just tricking us, as well.

It was Bob who’d taught her that only the strong can win, that weakness should be mercilessly exploited. It was Bob who’d turned her into—why not say the word?—a murderer.

“Stone Mattress”

That paragraph precedes the double carriage return which time jumps us from Verna’s memory of rape to the day of Bob’s murder.

It turns out Verna gives Bob many opportunities to prove himself worthy of living, but he fails her tests.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Once Verna decides to kill him, she doesn’t waver from her path.

In woo-woo world, the number 222 is supposed to be a sign that you’re on the right path and that you’re about to start a new cycle in your life. I wonder if that’s why Atwood chose 222 as Bob’s room-number. (Other storytellers make use of it as well, e.g. in Your Honor, which the judge is blackmailed for $222,000.)

Verna uses a stromatolite (stone mattress) to kill Bob The Rapist.

What do you call the rhetorical device of ending a list with something unexpected?

It’s paltry. It’s vicious. It’s normal. It’s what happens in life.

“Stone Mattress”

Paraprosdokian. Greek for “beyond expectation”. Since surprise is at the base of humour, paraprosdokian mostly has a comic effect.

Significantly, Bob is happy to break the rules and go with Verna where they’re not supposed to go: out of sight. Verna already knows that Bob doesn’t care about rules. And laws. He is literally killing himself, in a way, via his very own shortcomings.

Following the murder, Atwood switches to the future tense (“will”) and future perfect (“will have”). We now have an example of sideshadowing. This is how things might go. But it might not.

ANAGNORISIS

Readers are left with the belief that if Bob the Rapist had showed just an iota of self-reflection and genuine attentiveness to Verna, who could be any attractive generic woman on a ship, then he would have been spared. But he did not.

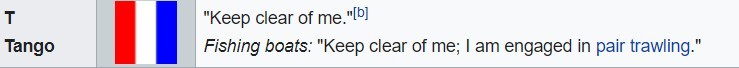

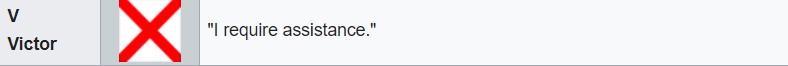

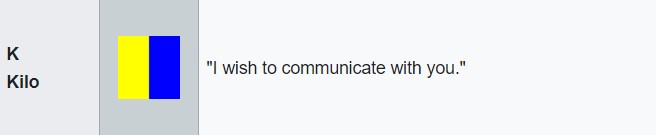

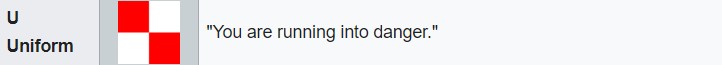

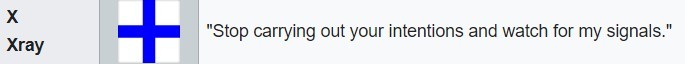

When I see this nautical flag, I always think of sexual assault:

Generation after generation of sailors have no trouble at all reading nautical flags. I don’t believe that teaching boys to ‘read the signals’ goes far enough in preventing sexual assault. I mean, it’s a start, if that’s the problem in the first place.

Every reader will bring their own experiences to this story. That’s always the case for lyrical short stories, though perhaps even more true for this one.

Like Verna, I’m at a place where I don’t believe ‘failure to read sexual signals’ is the problem. My worldview is a lot more weary these days. The issue that won’t budge: Predatory men simply don’t care about consent. We live in a gender hierarchy, and certain men very much enjoy their privilege sitting at the top of it.

Bigotry comes in various forms. Studies have shown that some types of bigotry are harder to shift than others. Racism is hard to shift and so is misogyny.

Misogyny is by its nature different from the bigotry directed at the rainbow community. LGBTQIA+ bigotry is (fortunately) of a different nature. While we still have a long way to go, the rainbow community has come a long way in the past 50 years. Attitudes shifted remarkably quickly on a sociological timescale, because bigots have nothing to personally lose when deciding to accept people with different gender identities and sexual orientations.

However, misogynistic bigots are a different type of bigot*. They know that if women were afforded genuine equality, power is still a zero sum game.

This is precisely why Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, in 2019, took the opportunity of International Women’s Day to say this: women should “rise” but not “on the basis of others doing worse”.

He understands that when a woman is Prime Minister, he himself is not Prime Minister.

In “Stone Mattress” Atwood offers no answers for how to correct this state of affairs. No one does, not even philosopher Kate Manne at the end of her wonderful book Down Girl. Instead, Atwood offers a sardonic take and a sorry imaginative end to a privileged Bob.

*For more on different types of bigotry, listen to the "Radically Normal" episode of Hidden Brain (March 9, 2021).

NEW SITUATION

Those Victorians always coupled sex with death.

“Stone Mattress”

The story has come full circle. For Verna, her first sexualised experience was done to her, not with her, and was itself a type of death.

Does revenge make us feel better? Here’s what the research says:

Getting revenge felt good. … “Revenge can feel really good in the moment,” he says, “but when we follow up with people five minutes, 10 minutes and 45 minutes later, they actually report feeling worse than they did before they sought revenge.”

Why Getting Even May Make You Feel Worse In The Long Run

Verna is fictional, so whether Verna feels worse is a moot point. What does not make us feel worse? Enjoying that momentary frisson of fictional revenge in a story.

For Verna, who will never get her untraumatised life back, this murder is a pyrrhic victory.

If he shows me any baby pictures, Verna thinks, I’ll hit him.

“Stone Mattress”. Verna herself has not had grandchildren.

Though Verna has displayed an exemplary memory for lines of poetry and the male poets who wrote them all through the story, at the end she cannot remember which of them coupled sex and death. (John Donne?)

Over Verna’s adult life, the Great Romantic poetry has been associated with men. She ‘can’t’ remember the poet because she no longer has to keep thinking about those men. ‘Her memory isn’t what it was’ not due to ageing and dementia, as we usually mean, but time iteself has shifted in the course of avenging a wrong done many deacades ago, but whose trauma has remained in her constant present.

‘But the details will come back to her later’ suggests that this moment of joy will be short-lived. That’s how vengeance works, and also, if trauma were healed so easily, more victims would surely do it.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Homes and Treisman of The New Yorker podcast ask instead, “Will Verna get away with this? Who’s looking for Bob?” They conclude the story itself is written in light-hearted manner, which suggests Verna will get away with it.

RESONANCE

After reading “Stone Mattress” I’m thinking about a retributive justice event in my home country which happened back in 1984. Six woman vigilantes kidnapped an Auckland University lecturer and assaulted him for allegedly functioning in a position of power as a serial sexual predator. There were no legal avenues supportive of victims of sexual assault in that era.

This incident triggered debates about gender politics and divided New Zealand. Retributive justice is out of fashion, and for good reason. Likewise, vigilante justice rarely goes well. Yet this is one of the standout incidents which led to social change.

There is now a documentary about it called Six Angry Women.

Works of the imagination, such as “Stone Mattress” can provide imaginative retribution even when, in the vast, vast majority of cases, no retribution at all will be found.♦

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

SIMILAR IN PLOT

The basic plot of “Stone Mattress” may remind you of a well-known story by Roald Dahl. Like Atwood, Dahl also wrote revenge fantasies for adults but, unlike Atwood, Dahl seemed to enjoy revenge for its own sake. He would drum up diegetic reasons for exacting revenge, so that the audience could then enjoy the spectacle of it.

The story I’m talking about is “Dip In The Pool“, also published in The New Yorker (1952). A man on a British cruise ship is about to lose a lot of money. He’s made a gamble about how fast the ship will be travelling, and, the ship is travelling too fast. So he decides to jump into the sea. His inevitable rescue will slow the journey, swinging the bet back in his favour. Dahl being Dahl, this trickster makes a grave error, and ends up drowning. Since he was trying to change a deal he’d already made, the audience feels no sympathy for him. The man is a hapless archetype.

In another Roald Dahl story, “Lamb To The Slaughter“, a wife kills her husband with a leg of lamb and then successfully encourages the policemen to eat the murder weapon. This plot point, too, is the very same Atwood utilises in “Stone Mattress”.

But when Margaret Atwood writes a revenge story, she is not simply offering her readers schadenfreude, catharsis, and the sweet, sweet taste of revenge. Atwood is delivering a political message, there for readers in a position to receive it.

SIMILAR IN COMEDY RECLAMATION

Although “Stone Mattress” turned out not to be a story about a gold-digger on a cruise, women have long since taken the gold-digger trope and used it for their own comedy ends. A tentpole example is the 1957 rom-com film How To Marry A Millionnaire.

1980s movie Dirty Rotten Scoundrels is cringe-worthy for its ableism but has since had a remake more clearly aimed at a female audience. A gold-digging trickster woman wins the day.

SIMILAR IN TONE AND SYMBOLISM

At The New Yorker, Treisman and Homes compare “Stone Mattress” to “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson. Both “appeal to a darkness that often goes unspoken.” “The Lottery” also features a stoning.

The symbolism of the stone is “classical, almost Biblical”. In John 8.7 Jesus tells people accusing a woman of adultery, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.”

In idiomatic English, ‘to cast the first stone’ means to act self-righteously; to accuse another person while ignoring one’s own indiscretions. Verna suffers this at the Home For Unwed Mothers.

In addition to their scouring and peeling chores, they were treated to bouts of prayer and self-righteous hectoring.

“Stone Mattress”

Homes and Treisman also recall one of Milton’s most famous lines: “calm of mind, all passion spent.” John Milton (1608-1674) was an English poet. The quote is from “Samson Agonistes” and is the final line of verse in a narrative about a ruthless conqueror finding respite after a great military struggle. Importantly for this comparison, the story of Samson Agonistes is of a man brought down by the woman in his life.

Other authors who also deal with deeply female concerns in their fiction “with strength, violence, passion and anger”:

- Patti Smith

- Joni Mitchell

- Angela Carter

- Grace Paley

SIMILAR CANADIAN ORIGIN

I want to add Alice Munro to their list, except Munro is too polite. Munro does come up in Homes and Treisman’s conversation, with the analogy being that both Munro and Atwood are Canadian, and both authors make use of geological features in their writing. The theory is that geology is more important to Canadians. (Homes says that Americans are more likely to be killed by pot holes, though I’m sure she’s not thinking of Annie Proulx when she says this.)

Header illustration: 1949 March cover of Fortune magazine by Arthur Lidov. This cross-cut image of a ship under construction almost looks like a horror face. It also says “Men of Shipping” as a caption, which is why I chose it. Men have historically owned certain spaces, both physical and mental.