Anagnorisis is a moment in a work of fiction when a character makes a critical discovery. Even for plotters rather than pantsers, this is the part of writing that often emerges in the process of storycrafting.

Aristotle thought a lot about how stories are structured and noticed that stories typically contain reversal and recognition. Reversal often means something different to storytellers these days, but Aristotle was talking about a main character’s reversal of fortune (e.g. in a rags to riches tale). By ‘recognition’, Aristotle meant the moment when a main character realises what has taken place (with horror or delight). The concept of anagnorisis has been around for a long time, and complete, satisfying stories still require this step.

Some people call it an epiphany, especially when talking about short stories.

It seemed to her that she had never known what the night was like before. Up till now it had been dark, silent, beautiful very often – oh yes – but mournful somehow. Solemn. And now it would never be like that again – it had opened dazzling bright.

Katherine Mansfield

Others call it a ‘leap’, as in a ‘leap of understanding’. Teachers talk of ‘aha moments’, scientists of the Eureka effect.

Oftentimes in story it is far more gentle than that, or happens fleetingly.

If you’re writing a piece of fiction, I’d urge you not to try to show anything—instead, try to discover something.

Ethan Canin

What is the purpose of writing? For me personally, it is really to explain the mystery of life, and the mystery of life includes, of course, the personal, the political, the forces that make us what we are while there’s another force from inside battling to make us something else.

Nadine Gordimer

The concept of anagnorisis links to a long human history of religious morality. Not surprisingly, storytelling is influenced by this way of viewing humanity, even in a non-religious modern story. The more common term ‘revelation’ is similar to the 2016 word ‘woke‘ — while it has its origin in religion, the concept is far wider than that.

Religions also differ in how they value personal epiphanies. LDS is a faith that places particular emphasis on feelings as a basis for knowing what to do or what decisions to make.

I had a grace descend down on me.

Bill Henrickson, Big Love

“Then came the most exquisite moment of her whole life passing a stone urn with flowers in it. Sally stopped; picked a flower; kissed her on the lips. The whole world might have turned upside down! The others disappeared; there she was alone with Sally. And she felt that she had been given a present, wrapped up, and told just to keep it, not to look at it — a diamond, something infinitely precious, wrapped up, which, as they walked (up and down, up and down), she uncovered, or the radiance burnt through, the revelation, the religious feeling!”

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Anyone immersed in Evangelical purity culture will recognise the constant references to healing, regeneration, renewal and rebirth. The story with the revelation is highly attractive to us, and can be repackaged for nefarious purposes.

He allowed himself to be swayed by his conviction that human beings are not born once and for all on the day their mothers give birth to them, but that life obliges them over and over again to give birth to themselves.

Love in the Time of Cholera, Gabriel García Márquez

THE RELIGIOUS ORIGIN OF REVELATION

Epiphany is a religious term and refers to the Twelfth Day of Christmas.

Religious thought from around the world has shaped our storytelling. A story which includes a anagnorisis is therefore a universal story.

Millions of people never analyze themselves. Mentally they are mechanical products of the factory of their environment, preoccupied with breakfast, lunch, and dinner, working and sleeping, and going here and there to be entertained. They don’t know what or why they are seeking, nor why they never realize complete happiness and lasting satisfaction. By evading self-analysis, people go on being robots, conditioned by their environment.

Paramahansa Yogananda (Indian guru and yogi)

Americans and Christians in particular will be familiar with The Redemption Story, which has its own specific story structure.

In movies, anagnorises are often shot on a hill, or in some other high place like the top floor of a building.

Damascene Moment: “A seminal moment, in reference to the conversion of Paul the Apostle on the road to Damascus.”

The film Contact features Jodi Foster sitting in an elevated spot in the desert at the end of the movie — she now has a much better view on the world and its place in the universe.

In Charlotte’s Web, for instance, the part where Wilbur gains his understanding of death occurs with the part where Fern is at the top of the Ferris wheel.

For more on this, see The Symbolism of Altitude. It all comes from Moses On The Mount, of course. Or maybe the Bible stories are based on much, much older storytelling conventions. Maybe there’s something about being up high which allows humans to see things differently. (Cats get it.)

True self-analysis is the greatest art of progress.

Paramahansa Yogananda (Indian guru and yogi)

The following demonstrates the close connection between death and enlightenment:

Since our consignment to heaven or hell was to be decided at the hour of death, the ‘good death’ became increasingly significant. Early Victorians idealised the notion of an end slow enough to give the dying the chance to say goodbye to their families and to prepare themselves spiritually for this all important moment. Families would cluster around bedsides, hoping to catch profound last words of their loved ones or witness religious raptures before death. Heavily edited stories of death scenes were expounded in Evangelical memoirs and journals, highlighting the dramatic battle of the dying in the days before death. The reality however was less romantic, leading many to comment on how rare that much romanticised rapture was. Indeed by the late Victorian period people had largely discarded these notions, hoping instead for quick, painless deaths over melodramatic, drawn out affairs.

Victorians and the Art of Dying

THE EMOTION OF AWE

The emotion most associated with the experience of anagnorisis is ‘awe’, which psychologists have been working to understand. According to Andy Tix, the transformative kind of ‘awe’ looks like this:

- It overwhelms individuals with something that transcends their current knowledge or understanding of the world.

- It immerses them in the process of trying to accommodate what previously was known with what currently is being experienced.

- It involves feelings of smallness or humility in the presence of something greater.

- It results in a profound change in thinking or behaviour, even in self-definition.

- The subject retains a vivid long-term memory of the event.

- Awe occurs very infrequently, maybe even only a few times in life.

ANAGNORISIS EXISTS ON A CONTINUUM

Just as there are strong desires and low-level desires, sometimes a character has a Eureka Moment (that’s what TV Tropes calls it), and at other times they realise something, sort of, in a nebulous kind of way.

Genre stories tend to have a stronger anagnorisis than more literary/lyrical stories, which can get away with revelations far more subtle. In some types of lyrical short stories the character almost has a revelation, then ignores it. Examples are plentiful in Katherine Mansfield’s modernist stories, but also in modern ones, such as Helen Simpson’s “In-flight Entertainment“.

THE ANTI EPIPHANY

I prefer to remain unenlightened, to better appreciate the dark.

Erin Morgenstern, from ‘The Night Circus’

“The more you realize, the more you realize there is nothing to realize,” she said. “The idea that there’s somewhere we have got to get to, and something we have to attain, is our basic delusion.”

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

Sometimes in a story there is opportunity for an epiphany, but the character suppresses the truth just revealed. Some people call this phase of story the antiepiphany. It often looks like a return to the quotidian mundanity of life.

Short stories don’t have time to dwell in the antiepiphany phrase. In his novels, Joyce takes his characters back to the mundane, but in his short stories end with the epiphany. Likewise, Mansfield doesn’t have time in a short story to show us the ordinary life Laura has woken up to the day after “The Garden Party”.

In some stories, the character has no revelation but the reader does, on their behalf.

Annie Proulx likes those ones.

There is only so much revealing one can do. For every self-revelation, there has to be a self-concealment.

from an interview between Susan Sontag and Geoffrey Movius

In Japanese, the concept of yūgen has been used to describe the gap where an ephiphanic moment might otherwise be. Michael Myers talks about yūgen in a paper comparing a story by Flannery O’Connor (Wise Blood) to a story by Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki (Portrait of Shunkin):

O’Connor’s use of a yūgen-type image differ in that the epiphanous moment, the explicit insight into beauty or spirituality, is lacking. It comes but is delayed until the end of the book.

“Wise” Blood and the Japanese yūgen Aesthetic in The Flannery O’Connor Bulletin

Vol. 21 (1992), pp. 58-72

Especially in the context of what might otherwise be a Christian sort of epiphany, the word ‘apostasy’ may come in handy. (Apostasy is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person.)

Psychologists call the absence of epiphany ‘denialism’.

As Richard Sennett has argued: “In practising social civility, you keep silent about things you know clearly but which you should not and do not say.”

Just as we can suppress some aspects of ourselves in our self-presentation to others, so we can do the same to ourselves in acknowledging or not acknowledging what we desire. Most of the time, we spare ourselves from the torture of recognising our baser yearnings. But when does this necessary private self-deception become harmful? When it becomes public dogma. In other words: when it becomes denialism.

Denialism: what drives people to reject the truth from The Guardian

But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, but can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty in it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties.”

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows

See also: We All Half Know Things. I offer examples of half-knowing from real life.

ANAGNORISIS AS COLLABORATION BETWEEN WRITER AND READER

A story on its own doesn’t offer any sort of emotional lesson. Instead, lyrical stories are a collaboration between writer and reader. Imagine three entities sitting around a table: character, narrator and reader. The literary work sits on a plate somewhere on the table.

At the anagnorisis part of the story, a reader can take a biscuit from that plate, or leave it.

Likewise, the writer can push the plate closer to the reader, urging readers to take from it.

The character can take a biscuit from the plate, which might encourage the reader’s mouth to water and reach for a biscuit themselves. Or, the character can look directly at the plate of biscuits and flip the table, in which case the reader learns something by negative example.

ANAGNORISIS IN MYTH

In Greek mythology, a phoenix is a long-lived bird that is cyclically regenerated or born again.

Associated with the Sun, a phoenix obtains new life by arising from the ashes of its predecessor. According to some sources, the phoenix dies in a show of flames and combustion, although there are other sources that claim that the legendary bird dies and simply decomposes before being born again.

Wikipedia

At the beginning of 2018, Uma Thurman opened up to the media about her experiences with Weinstein and Tarantino. Following in from this, Jessica Chastain said the following in a series of tweets: I keep imagining Tarantino spitting in Uma’s face and strangling her with a chain for KILL BILL. How many images of women in media do we celebrate that showcase abuse? When did this become normalized ‘entertainment’? When violence against women is used as a plot device to make the characters stronger then we have a problem. It is not empowering to be beaten and raped, yet so many films make it their ‘phoenix’ moment for women. We don’t need abuse in order to be powerful. We already are.

Jessica Chastain

PHOENIX MOMENT

Chastain’s phrase ‘phoenix moment‘ is a useful one. I consider this a subcategory of the anagnorisis phase in storytelling, and one which is highly problematic when used time and again with certain groups of people. It’s not the phoenix moment itself which is the problem, but the sequence of abuse scenes leading up to that moment.

CHERNOBYL MOMENT

In the wake of the Australian bushfires of 2019-20, the media talked also about ‘Chernobyl moment‘, as in, “will this be Australia’s Chernobyl moment” when we come to understanding the full impact of climate change?

ANAGNORISIS AND LYRICAL SHORT STORIES

The anagnorisis section is especially complex in lyrical short stories, which frequently present the mundane in a new way.

The daily papers talk of everything except the daily. The papers annoy me, they teach me nothing. What they recount doesn’t concern me, doesn’t ask me questions and doesn’t answer the questions I ask or would like to ask.

What’s really going on, what we’re experiencing, the rest, all the rest, where is it? How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs every day: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual?

To question the habitual. But that’s just it, we’re habituated to it. We don’t question it, it doesn’t question us, it doesn’t seem to pose a problem, we live it without thinking, as if it carried within it neither questions nor answers, as if it weren’t th bearer of any information. This is no longer even conditioning, it’s anaesthesia. We sleep through our lives in a dreamless sleep. … What’s needed perhaps is finally to found our own anthropology, one that will speak about us, will look in ourselves for what for so long we’ve been pillaging from others. Not the exotic any more, but the endotic.

To question what seems so much a matter of course that we’ve forgotten its origns. To rediscover something of the astonishment that Jules Verne or his readers may have felt faced with an apparatus capable of reproducing or transporting sounds. For that astonishment existed, along with thousands of others, and it’s they which have moulded us.

George Perec

DIFFERENT GENRES HAVE THEIR OWN KINDS OF SELF-REVELATIONS

As one example, romance genres require that at some point the main character/s realise they are in love. This love is usually of the romantic kind. (There are other kinds.)

Those epic big screen lip-locks aren’t just selling mouth pleasures, they’re selling Moments of Realization, too, when (at last!) everybody knows for sure that they’re in a love story.

Captain Awkward, who also does a great job of describing how a typical fictional romantic plot can unhelpfully shape our expectations of our relationships in real life.

ANAGNORISIS IN OTHER FORMS OF STORYTELLING

SHORT STORIES

In the world of short stories, this moment is often called an epiphany, a Joycean epiphany, or the epiphanic moment. The ‘A-ha Moment’. However, these other terms often feel too strong for many types of story.

KATHERINE MANSFIELD

As mentioned above, the Literary Impressionists such as Katherine Mansfield distinguished their form of storytelling by rejecting the epiphany, instead writing under the idea that people don’t really change all that much. And even when opportunities for change arise, characters often fail to heed the warnings, and keep plodding on as before — to their own detriment.

ALICE MUNRO

Ulrica Skagert (2008: Possibility-Space and Its Imaginative Variations in Alice Munro’s Short Stories) writes of “The Shock of Recognition” typical of a reading experience of Munro.

This phrase comes from Herman Melville who was talking about the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The Shock of Recognition refers to “an appearance of something that we have been unaware of so far, but that still lies dormant in us; it is something that we re-cognize in the act of discovering it”. (The hyphen in re-cognize is important.)

Skagert offers Alice Munro’s “Images” as an excellent example of a story which offers “The Shock of Recognition” at the Anagnorisis part of the narrative. Here’s what it looks like on the page. It won’t make much sense without the wrapper of story, but notice the image of the lightning bolt, which you also see in the language of cartoons:

People say that they have been paralyzed by fear, but I was transfixed, as if struck by lightning, and what hit me did not feel like fear so much as recognition. I was not surprised. This is the sight that does not surprise you, the thing you have always known was there that comes so naturally, moving delicately and contentedly and in no hurry, as if it was made, in the first place, from a wish of yours, a hope of something final, terrifying.

“Images” by Alice Munro

A satisfying ending is one that delivers on the promise, providing new insight or comfortable confirmation or vicarious happiness. Even when it’s surprising in some way, the ending feels inevitable, because it fulfils the promise of the story. And—this is important—the ending feels satisfying only because the beginning set up the implicit promise in the first place.

The ending must make use of those same forces and conflicts, with nothing important left out and nothing new suddenly appearing at the last minute.

Mr. Shakespeare: Every character in your story doesn’t need to know how everything works out for everybody as long as your reader knows. These final scenes are unnecessary and they slow down the action at the end because, frankly, we’ve all heard all of this explanation already. Sometimes twice already. So essentially the audience/reader is forced to sit through a summary of the action while all the characters get caught up.

The Literary Lab, Loose Endings

PRESTIGE TV

- Walter White has the opportunity to do the right thing and hand himself in when Hank discovers who he really is. But he decides to run instead. He does have a slow, hard-earned self-revelation, though. He acknowledges that he hasn’t been doing it all for his family, but for himself.

- Despite not changing much, Don Draper in Mad Men does face a number of moral dilemmas, mostly centred upon people finding out who he really is. He decides to continue living as Don Draper, but has regular lapses back into his old, less privileged life. When Don has his Joycean epiphany, that’s when the storytellers decided to leave him. (I imagine he becomes insufferable after that.)

- In Big Love, Barb, as first wife, has already faced a number of massive moral decisions at the beginning of the story. Backstory eventually reveals to the audience that Barb had the opportunity to leave Bill when he took on his second wife. Barb is constantly tested, especially when her natal family and her church reject her, leaving her isolated from the rest of the world. The most noticeable character arc in Big Love is the character of Margine, who is so young that she is the main character in a coming-of-age story. At the beginning she is a teenager (revealed in a later season to be younger than initially depicted), but in the end Margine is a self-actualised woman, and makes the best of her polygamist situation to live what is actually a pretty feminist life.

But a complete narrative does seem to require something akin to anagnorisis, even if that thing is a recognition of lack: Even when characters learn absolutely nothing, perhaps because they are irredeemably stupid or immoral, the audience needs to get something out of the story.

Dan Harmon outlines the basic skeleton of any good story:

- A character is in a zone of comfort (BUT THEY DO NEED A SHORTCOMING)

- But they want something (DESIRE)

- They enter an unfamiliar situation (OPPONENT)

- Adapt to it (PLAN)

- Get what they wanted (OR NOT, IN A TRAGEDY)

- Pay a heavy price for it (BIG STRUGGLE)

- Then return to their familiar situation (IN HOME-AWAY-HOME STORIES, WHICH NOT ALL OF THEM ARE)

- Having changed. (NEW SITUATION)

ANAGNORISIS IN COMEDY

Or, absence thereof…

We love comedic characters precisely because they never learn. Failing to learn from mistakes is a compulsory psychological shortcoming for a comedic character in an ongoing series.

In comedy — specifically ongoing comedy series, either sit-coms or novel series — there will be no Anagnorisis on the part of the main character. Comical characters are highly flawed, and if they were to learn from their experiences they would get boring and staid. George Costanza never learns from his errors. Nor does Greg Heffley. Even when a comedic character does have a minor Anagnorisis, they’ll have forgotten it by the beginning of the next story, arriving in statu nascendi.

If it’s a stand-alone comedy story, however, the main character is quite likely to learn a big lesson. Groundhog Day is one example.

What does happen, though, especially in comedies for children: The audience has a minor Anagnorisis. Spongebob Squarepants features characters who never learn, yet each episode is mock-didactic. For the viewer. (Didacticism is coded as mock-didacticism in comedy.) Episodes end like a Charles Perrault fairytale, with a summary of a moral lesson.

Likewise, in Courage The Cowardly Dog, the viewer is reminded of the exact same lesson over and over — be nice to others because they can help you out. (Listen to Courage because he’s always the first to detect baddies.)

TYPES OF ANAGNORISIS

CHARACTER LEARNS SOMETHING ABOUT THE PLOT

This is called a plot reveal. This will surprise the reader if not the character. Annie Proulx’s “In The Pit” is a good example of this kind of proxy-Anagnorisis. In a twist ending you’ll always have a big reveal (possibly with delayed decoding), and in this case you probably haven’t got a character driven story but a plot driven one. I’m arguing that where there is no Anagnorisis phase in a character driven story, the storyteller needs at least a proxy for that, otherwise the story will seem unfinished to the reader.

CHARACTER LEARNS SOMETHING TRUE ABOUT THEMSELVES

It’s a beautiful thing to be understood, but a powerful thing to understand yourself.

iambrillyant

This is the best outcome for a character and makes any pain endured across the story worth the effort.

In many stories, a character has a story about themselves which isn’t especially true. This is the case for all of us — there must always be a gap between who we think we are and how we really are. This is unavoidable, but in stories, characters uniformly do better when they understand who they really are, shortening the dramatic irony between who they are and who the audience can see them to be.

The job for the storyteller, then, is to establish that gap at the beginning of a story.

Episode one of season three of UK crime drama Happy Valley does this beautifully with the main character, Catherine Cahill, who is counting the months down to retirement after a 30-year, event-filled career. While enjoying a drink with her younger sister, she says:

CATHERINE: You know, most police officers die within five years of retirement.

CLARE: Why?

CATHERINE: Because they can’t let go. I don’t know. Cos they’ve got nothing better to think about. because the job’s made them all bitter and twisted. Whereas me, I’m counting the seconds. I mean, don’t get me wrong. I’m very proud of me 30 years. I’m the best copper that ever lived. But Code 11, job done. I think most of them think that’s it, end of. But me, I’m just becoming the person I’ve always wanted to be. Don’t take shit off anyone any more. I say it like it is. I know who I am, finally. And I now know the be-all and end-all in’t necessarily to get myself hitched to the first useless, flaky twat of a man who happens along.

CLARE: Mm. You’ve always been like that.

CATHERINE: Yeah, but I’m feeling it now.

CLARE: Rock on.

Happy Valley, E01 S03

The exchange above suggests Catherine Cahill has a devil-may-care attitude regarding what others think of her. But several scenes later, Catherine is in a different context. Work. Catherine’s workmate, Joyce, is trying to organise a retirement function for her.

The conversation between these two tells the audience that Catherine’s self-image does not line up perfectly with who she sees herself to be, or even who Catherine’s younger sister sees herself to be. There’s still growth to be had before Catherine gets to retire:

JOYCE: Oh, for God’s sake, what’s up with you?

CATHERINE: Well, you didn’t have a retirement do!

JOYCE: I haven’t retired!

CATHERINE: From being a copper, you did.

JOYCE: I think we had a little drinks do.

CATHERINE: But I’m not popular like you are. I’m not popular.

JOYCE: You are! In certain circles, you are. They’d probably all just turn up to take a pop and say good…

CATHERINE: What do you mean, in certain circles?

JOYCE: You are popular in certain circles.

CATHERINE: Well, in what circles am I not popular?

JOYCE: I don’t know. You tell me. You’re the one saying you’re not popular.

CATHERINE: Yeah, but who were you thinking of when…?

JOYCE: Nobody. When you said it? Nobody!

CATHERINE: Well, who was on your mind?

JOYCE: Well, there’s a few top brass you’ve p*ssed off over the years, aren’t there? There was that time that you told Mike Taylor to shove his pips up his a*se. Think that might have been a game-changer. Anyway, you’re very popular with… the troops, the gang, the rank and file, aren’t you? When you’re not upsetting them.

CATHERINE: I’ve just done my job. I’ve toughened them up. I’m sorry if that makes me unpopular.

JOYCE: You didn’t have a little drinks do. I did!

CATHERINE: Well, I don’t remember coming.

JOYCE: Were you sulking?

CATHERINE: It’s either that or you didn’t invite me.

JOYCE: Why would I not invite you? Of course I invited you.

CATHERINE: I don’t think you did, Joyce.

JOYCE: Oh… Just forget it.

CATHERINE: OK.

JOYCE: It’s a wonder you have any friends at all.

CATHERINE: Well, I don’t, according to you. According to you, I’m Billy fvcking No-Mates.

Happy Valley, E01 S03

CHARACTER ALMOST LEARNS SOMETHING ABOUT THEMSELVES

These stories are vexing tragedies for the audience, who experiences an “If only!” reaction. The Wrestler is a great example of this. Randy the Ram comes so close to learning something about himself. If only he’d seen what the audience had seen about him he could’ve improved his life.

“I make all my movies about pretty much the same thing. It’s ultimately death and being alone. It’s existentialism. The meaning of life. All of those big things that would seem obnoxious if I went on about them. And a lot of my characters go through this: There’s an inciting event in your life that shows you who you are and who you have always been, and it’s equally thrilling and repulsive to realize that and that you are entirely alone.”

Jodi Foster

Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Personal epiphanies feel great, but they fade within weeks. Upon having an epiphany, make a plan and start actually changing behavior.

Less Wrong

CHARACTER LEARNS SOMETHING UNTRUE ABOUT THEMSELVES

This isn’t usual, but sometimes a character learns something about themselves which isn’t really true about them. The reader is given enough information to know the veridical truth of their character. The unreliable narrator is useful for this. Stories like this tend to have in common themes about how we can never really know ourselves.

Alternatively, the narrator knowingly gives us enough information to make up our own minds. A good example of this technique is Annie Proulx’s short story “Heart Songs“. Importantly, this faux-self understanding comes before the Battle scene, not after it, where it’s usually placed. Since the character is wrong about himself, it is the very thing that plunges him into the Big Struggle, not what helps him out come of it. We know these characters will never change. That’s the whole point.

Starting out sure about something then becoming less sure is another riff on Anagnorisis.

SOMETIMES IT’S NOT THE MAIN CHARACTER WHO LEARNS SOMETHING ABOUT THEMSELVES

It’s not always easy to pick which character is the ‘main one’. Is is the character we see the most of? The focalising character? Or is it the one who undergoes the anagnorisis?

Larry McMurtry’s film/book Hud features a main character (called Hud) who refuses to change. But those all around him do change and he is left all alone, which is the point. Don Draper didn’t change until right at the end, in a tacked on, cheesy kind of hippie way (in my opinion). But all the characters around him changed, mostly Peggy.

As Caroline Framke points out at Vox, “Don Draper spent seven seasons refusing to change at all. But others changed all around him. Joan realised that she could work sexism to her advantage for a longterm better future for herself and her son, then pull away entirely, to run her own business. Peggy’s story was a coming-of-age story, from country-girl to Manhattan cosmopolitan who didn’t feel she had to pretend to be someone she was not. Peter had the Anagnorisis that family comes first. Roger reflected on his own life and realised how he’d gone wrong. Don Draper came up with a good idea for a Coca-Cola advertisement.”

If your main character (e.g. Don Draper) does not change, others around them must. (Exception for comedy series, see below.)

ANAGNORISIS IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

If you’re writing a contemporary children’s story, the Anagnorisis better be experienced by the child.

This hasn’t always been the case — The First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature was full of adult characters who went through the character arc helped along by the innocence and inherent goodness of the uncorrupted child.

Adults in children’s books are usually stuck with their characters and incapable of alteration or growth. If they are really unpleasant, the only thing that can rescue them is the natural goodness of the child.

Alison Lurie: The Subversive Power Of Children’s Literature

Lurie offers Mrs Burnett in Little Lord Fauntleroy as the classic example of an adult whose only hope is the goodness of a child.

Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert go through late-life emotional maturity with the addition of Anne Shirley to the household. At least in Anne of Green Gables, Anne has her own emotional journey alongside the adults.

But even today, you’ll still find stories in which the child character exists as a tool in the emotional awakening of an adjacent adult.

A particularly egregious example is a DreamWorks movie, which I talk about in my post on how girls are too often asked to play this role. Girls are assumed to be more emotionally mature than boys, giving rise to ‘The Female Maturity Formula’ of modern storytelling. In that film, Dakota Fanning’s character behaves like a miniature adult mother. The adult men in her company mend their ways, with her leading by example.

When examining a story for diversity, avoid a simple tally of gender and ethnicity. Look instead at who gets to have all the Anagnorises. That tells you who the ’rounded humans’ are considered to be.

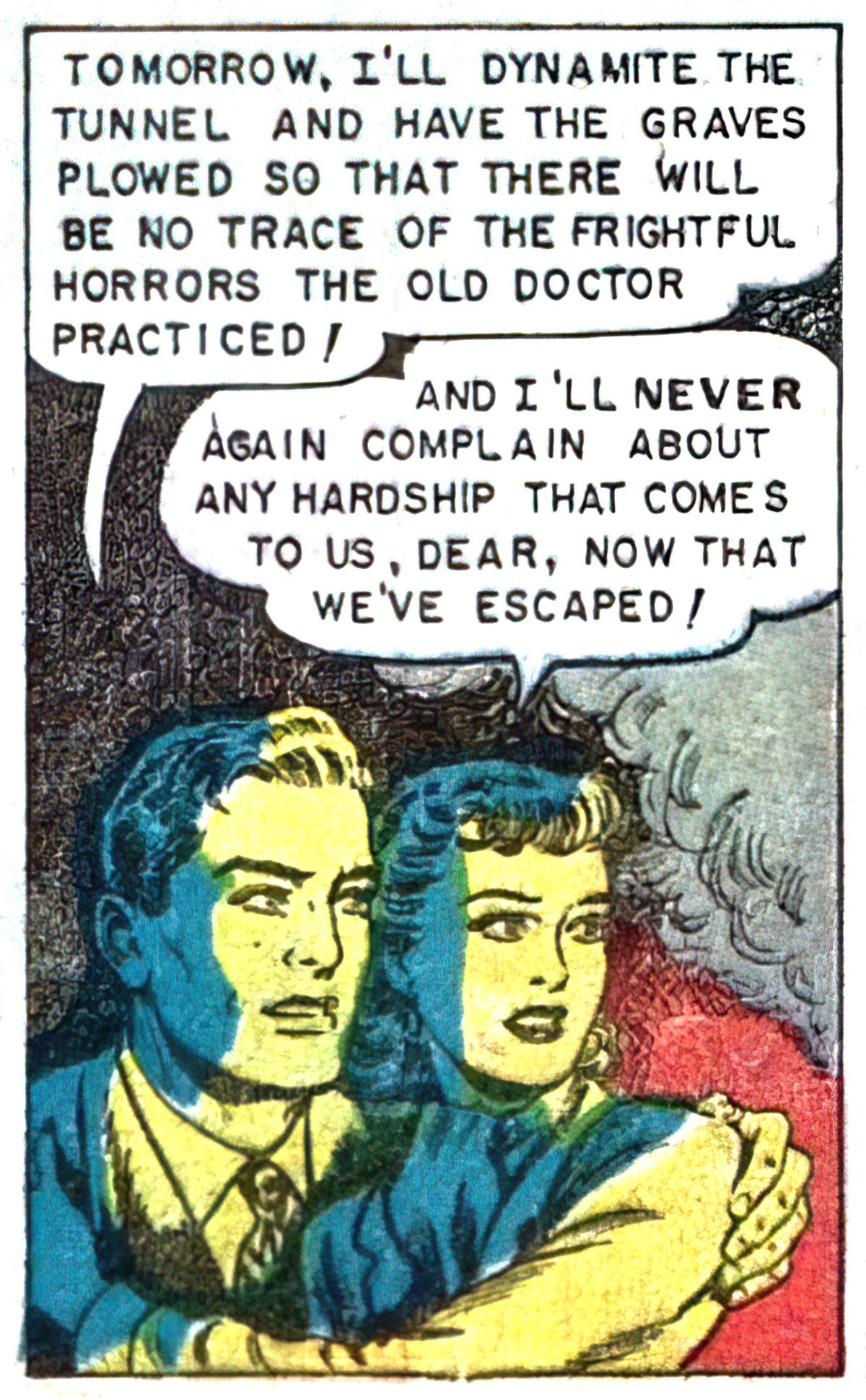

COMIC STRIPS

If you read comic strips, especially those from the mid 20th century, there will often be a panel with a very clearly expressed anagnorisis. Here: gratitude.

ANAGNORISIS AND THE LGBTQ SHORT STORY

The startling moment of recognition, understanding or disclosure that typifies the short story in general has particular salience for LGBTQ short narratives in which epiphany is structured by a character’s revelation of his or her LGBTQ identity, an act known as coming out. Such a revelation can not only provide the central moment of crisis in a story but, moreover, sometimes indicate a complete rupture of past and future for the LGBTQ character who comes out. […] Equally revelatory are moments in which characters discover unknown or unexpected LGBTQ friends, relatives, and communities.

LGBTQ America Today: An Encyclopedia Volume 3: P-Z edited by John C. Hawley, 2009

Related Terms

BREAKTHROUGH

After all these years, I have come to realise that I must go through a period of agony and torture before I have a breakthrough.

Hans Zimmer

CATHARSIS

the process of releasing, and thereby providing relief from, strong or repressed emotions. Catharsis is a subcategory of anagnorisis in which the audience empathises so keenly with the main character that they consciously or subconsciously connect the emotions to their own lives, feeling what the character feels. Removed by the filter of fiction, this can be revelatory and healing.

CATHEXIS

the concentration of mental energy on one particular person, idea, or object (especially to an unhealthy degree). Another modern word for this is monotropism. At the climax of a story mental energy becomes concentrated, in the empathetic character and ideally mirrored in the audience.

ERKENNTNIS AND WISSENSCHAFT

The German language usefully marks this as the distinction between tacit, incompletely articulated and intuitive knowledge (Erkenntnis) and knowledge that comes via science (Wissenschaft). The epiphany experienced by characters in stories is often of the Erkenntnis kind. English synonyms include: realization, recognition, insight, perception.

Erkenntnis relies on ‘interpretive’ knowledge. This is often what a storyteller is asking of the audience, also. If we experience epiphanies from reading, it’s probably because we’ve interpreted it ourselves rather than been told outright. Epiphanies are therefore often tacit, incompletely articulated and intuitive.

MIRROR MOMENT

A mirror moment is a moment in midpoint scene of a novel or screenplay when the character is forced to look within and reflect on who he is and who he must become in order to achieve his goal. If he decides to continue on as he always has, he will surely fail (tragedy).

If the story is not a tragedy, the hero realizes he must either a) become stronger to overcome the odds or b) transform, shedding his biggest flaws and become more open-minded to new ideas and beliefs. One way or the other, he must better himself in some way to step onto the path which will lead to success.

from Story Midpoint & Mirror Moment: Using Heroes’ Emotions To Transform Them

A successful ending must be tied not only to the author’s implicit promise and the forces dramatized in the middle, but also to the protagonist’s nature. A test for your ending is this question: If my protagonist were a radically different person, would this story still end the same way? The answer should be No.

Finding the right ending sometimes takes time. Once it took me thirteen years.

Nancy Kress, from Beginnings, Middles and Ends

What are epiphanies, and why do so many people so frequently experience them? Are they just transient phenomena in our brains, or are they the revelations of objective value that they very often seem to be? What do they tell us about the world, and about ourselves? How, if at all, do epiphanies fit in with our moral systems and our theories of how to live? And how do epiphanic experiences fit in with the rest of our lives?

These are Sophie Grace Chappell’s questions in this ground-breaking new study of an area of inquiry that has always been right under our noses, but remains surprisingly under-explored in contemporary philosophy.