Conflict: refers to the struggle or clash between two or more opposing forces or characters in a story.

This conflict can take many forms:

- a physical fight

- a battle of wits

- a clash of beliefs

- an internal struggle within a character

Conflict in storytelling creates tension, raises the stakes, and drives the plot forward. Conflict can also reveal important aspects of characters’ personalities, motivations, and values and, by extension, highlights the themes and messages of a work of literature.

Conflict requires two separate storytelling elements: Opposition and a Battle, or some other struggle.

Today I’ll talk about how writers set up opposition. For part two, see this post for discussion of the ‘battle’ or, as we might also call it, the big struggle.

KEY POINTS

- Every interesting main character in every story needs a worthy opponent.

- The main character learns through their opponent.

- The opponent attacks the main character’s great shortcoming.

- The main character deals with their own great shortcoming and grows as a result.

The cat sat on the mat is not a story. The cat sat on the other cat’s mat is a story.

John le Carre

Common writing advice: Stories need conflict. Every scene needs conflict. Without conflict your story will feel flat.

But what does conflict mean? It does not mean constant arguing.

Tension and Conflict Are Different

Tension and conflict are two different things. However, they work together, because tension is the anticipation or potential for conflict to happen. Conflict is the actual problem happening.

Writer Unboxed

I’ve also heard it said that every story has an apparent conflict and a discovered one.

I’ve come to believe that the whole concept of conflict is unnecessary so long as you’ve mastered the art of ‘opposition’. In other words, you need a character cast which includes a variety of opponents. You might have a classic villain, a friend who is secretly against you, a parent who is lovingly stopping you from reaching your goal, a monster in the woods, a helper who at first comes across as an enemy. If all these characters are in place, you won’t need to try to drum up conflict. Conflict will organically occur.

Surrogate Activities: The more we eliminate struggles from our lives, the more we create artificial struggles – sports, video games, culture wars – because the mind wants peace, but needs conflict.

@G_S_Bhogal

Too much conflict kills a story

It would be a disservice to all aspiring writers to say that all scenes need to have conflict to be emotionally engaging. [It’s important to] have an ebb and flow of tense versus relaxing scenes to maintain reader interest throughout your script. After a compelling crisis, the reader needs a scene of relaxation, relief, or humour, which is devoid of conflict. Too many dramatic scenes in a row will only lead to emotional exhaustion and possible desensitisation to additional conflict.

Granted, these types of scenes don’t have to be dramatic scenes, but you can still have a dramatic scene without conflict as long as you promise conflict through anticipation. (“Beware, the conflict will come soon” or rising tension (“Nothing is happening now, but it can come at any time, from anywhere”). Tension, especially the kind generated by dramatic irony in a previous scene, makes up for a lack of conflict. Hitchcock was the master of this, and North by Northwest is full of fascinating scenes devoid of conflict, which still could be considered dramatic, like the classic crop-duster scene. Even when Thornhill stands in the middle of nowhere, we are gripped. Why? Because the scene has dramatic irony from us knowing Eve has set him up and tension from what could happen at any time.

Writing For Emotional Impact, Karl Iglesias

Take what is negative, disguise it with a lie

Robert McKee has a tip for pushing conflict to its limit in a story:

You take what is negative—like hate. Then you do one of two things: Either you disguise it with a lie, so it becomes hatred masquerading as love—like in great films such as Ordinary People. Or you take what is normally directed at the world and turn it inward on the character, so hatred becomes self-hate.

Those are the two techniques to take what is common, everyday antagonism and conflict and push it one step further, to the limit of things. […]

You don’t just take hate and magnify it so there’s a lot of it—a volcano of it. It changes its quality. It becomes hatred masquerading as love. It becomes self-hate.

It does magnify the power of it, but not by being more and more of it—by changing the quality.

Robert McKee in this Vice interview

The usefulness of arguments

Another tip involving dialogue: If you want to give the audience some backstory via dialogue it can feel too ‘on the nose’ (too obvious). But it almost always feels less obvious if your characters are arguing with each other. Since I had that pointed out to me, I’ve noticed it a lot. “Oh, great, so you can sleep around with the woman two doors down but I can’t have my own bank account?” In this way, we accept more specificity when dialogue is argumentative? The exception is if you’ve had this technique pointed out to you, or noticed it yourself, in which case it no longer works.

Don’t avoid the big scene

Below, Melissa Hinshaw is telling writers not to avoid the Big Struggle stage of a story, which can never be left out.

I’ve been particularly pushy about this this year, but I want to see characters actually face and work through their conflict. There are a good number of stories I remember cutting because they ended at that moment right before something big happens—and I get that, as a writer, one hundred percent! That’s the moment where there’s all this great tension and you feel so much and you don’t wanna mess with it. But guess what? You have to. Because that’s how story happens. So that’s a big reason I pass on otherwise-great stories, and the next big reason is related to the step right after that: that moment of conflict. It’s very easy to be cliché in that moment of conflict, and it’s very easy to leave it like that because, well, you finally made it happen! Good job! But let the story sit for a couple of weeks, then come back and rework it so the dialogue or narration doesn’t sound exactly like every other moment of conflict in any other story. Successful moments of conflict contain the concretely-stated heart of the matter within this particular story, not an abstract commentary on how hard things are. They literally show you what’s at stake. They’re rarely actually subtle, but they also manage to feel subtle within the pace of the story.

Melissa Hinshaw

OPPONENT AS SUM TOTAL OF FORCES

So something happens to a central character that throws them off the beaten track and forces them into a world they’ve never seen. A beanstalk grows, a patient collapses, a murder is committed. All of these actions have consequences, which in turn provoke obstacles that are commonly dubbed forces of antagonism — the sum total of all the obstacles that obstruct a character in the pursuit of their desires. These forces accumulate from this initial moment as we head towards the climax of the story.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

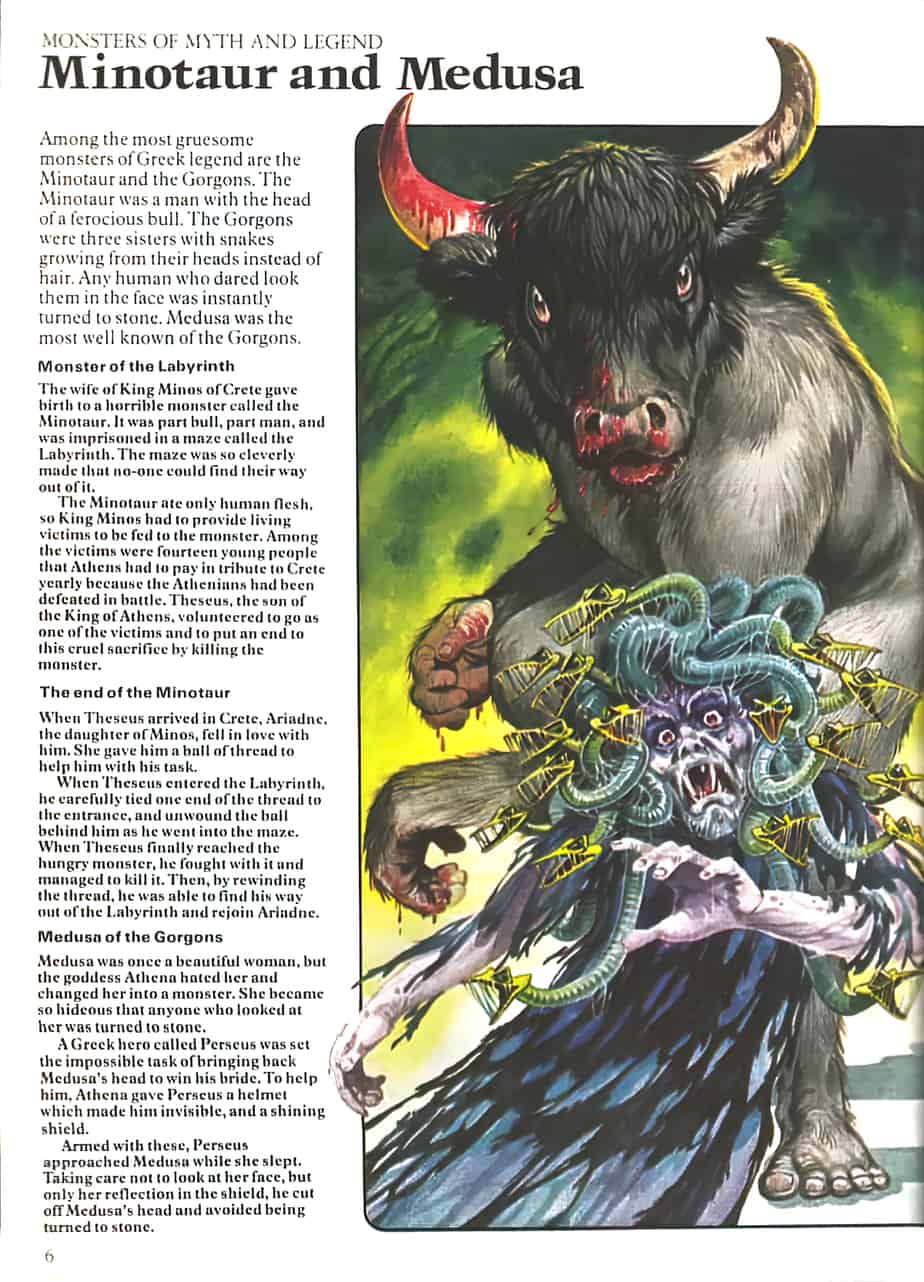

THE MINOTAUR VS HUMAN LAYERS OF OPPOSITION

The Minotaur is a really scary creature from Greek mythology — a part man, part bull monster who lives at the centre of a labyrinth. Because the Minotaur is so very scary, we can use him as a stand-in for any type of Big, Bad Baddie who threatens your main character’s very life.

Instead of the big bad opponent of Theseus, we might instead choose the bucentaur fought by Hercules or the dragon fought by Siegfried. Doesn’t matter. We’re talking about some kind of monster who stands in as the archetype of all mythic combat.

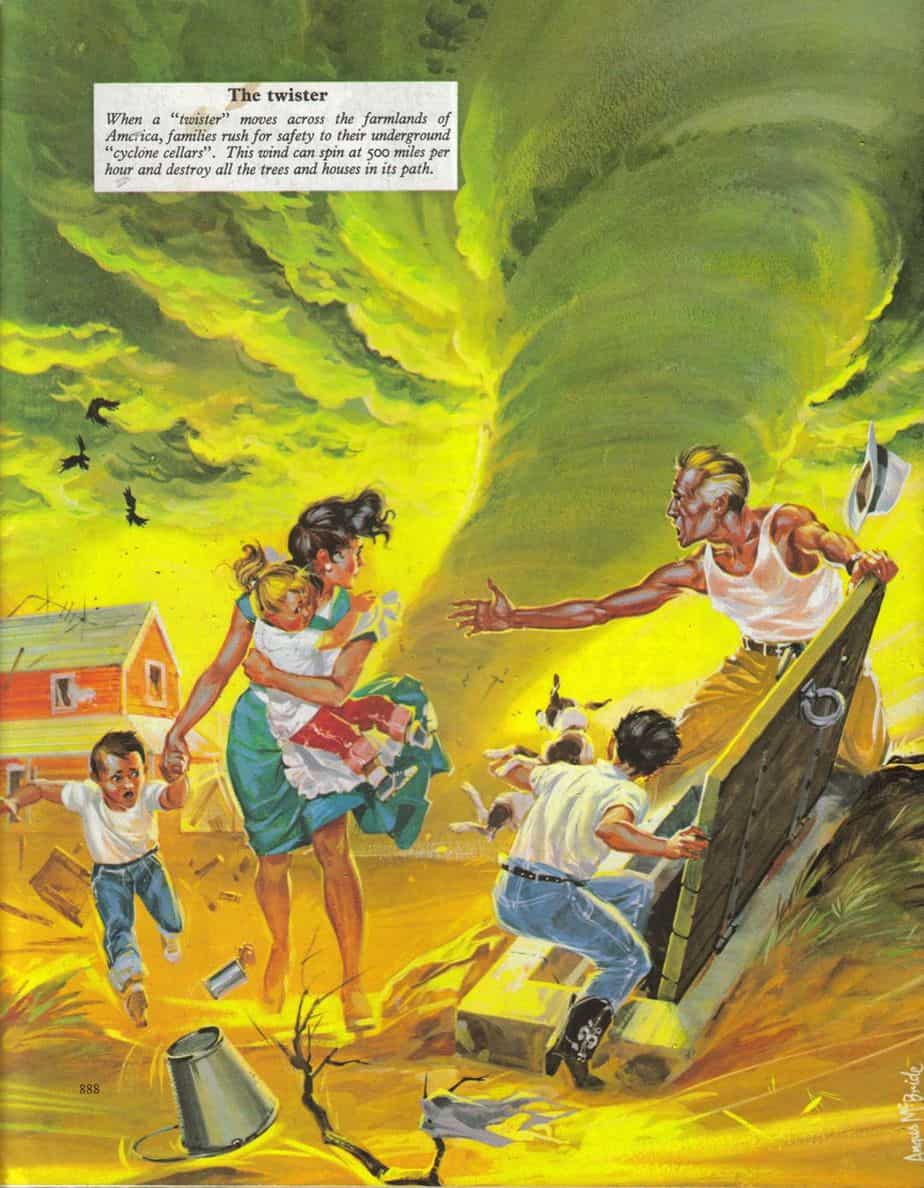

In most of the best stories the opponent will be another human but it can also be ‘nature’ (e.g. in a disaster movie). Where the opponent is ‘nature’, like in Twister, the Minotaur layer of opposition comes from the cyclone.

Three Days On A River In A Red Canoe by Vera B. Williams is a good example of a picture book narrative in which the main opponent is ‘nature’ rather than other characters: First it rains, thenthere is a gale, then the canoe almost overturns in the current of the river. Friction between the campers is hinted at, but they basically band together and fight against the opposition of weather and water current.

The problem with Minotaur opponents is that they aren’t inherently interesting. In fact one can easily be switched out for another — there is little to distinguish between a troll/ogre/tsunami/wolf or any number of mythical, archetypal villains.

The logline of It Follows sums up your archetypal Minotaur villain: It doesn’t think. It doesn’t feel. It doesn’t give up.

So what the storyteller needs, as well as the Minotaur, is a layer of human opposition. In the case of Twister, we have the rival storm chasers who serve as the humanised opponents.

In Arachnophobia, the spiders make for creepy but uninteresting opponents because their motivation isn’t to kill everyone — that just happens as default. They have no morals for us to judge. This is what makes Minotaurs (or spiders) uninteresting. Instead, the writers created a conflict between the old doctor and the bright young city slicker coming in to an unwelcoming community, where the older doctor refuses to step aside.

Importantly, not all stories contain a Minotaur layer of opposition. Traditional mythic stories do have this layer, but the new big struggle-free mythic form does not need one, because the main character thinks and feels their way through a difficult journey. She doesn’t fight a big, bad Minotaur.

Roger Ebert used the phrase ‘mad-dog killer’ to describe this kind of opponent.

Mad Slasher Movies: Movies starring a mad-dog killer who runs amok, slashing all of the other characters. The killer is frequently masked (as in “Halloween” and “Friday the 13th”), not because a serious actor would be ashamed to be seen in the role, but because then no actor at all is required; the only skills necessary are the ability to wear a mask and wield a machete. For additional reading, see Splatter Movies, by John (“mutilation is the message”) McCarty.

Ebert’s Guide to Practical Filmgoing: A Glossary of Terms for the Cinema of the ’80s

PROBLEMS WITH THE MINOTAUR OPPONENT

Part of the reason I believe these new big struggle-free mythic forms are so important is because the concept of the Minotaur Opponent speaks to an adaptive but problematic aspect of human psychology: We like to imagine uncontrollable events in humanised/monster-ised form.

An excellent example of this can be seen with the clarity of hindsight in early to mid-14th century Europe. This was the era when witch trials began. The concept of the witch’s sabbath came about for several other reasons, but what made the popular concept of the evil witch really take off? A little ice age. This created a climate crisis. No one could sow their crops let alone harvest them. This had a huge impact on social networks of the period, and no doubt had psychological effects, too. These days we might call it PTSD. Many people felt alienated from their communities.

Rather than feel helpless, people invented a scapegoat. In order for a scapegoat to work, first you need a narrative. Here’s why my crops are failing, my kids are starving and my livestock has foot rot: There are witches in my village.

This belief is easier to deal with psychologically than the belief that humans are utterly powerless under the forces of nature. It gives people something to do: Medieval Europeans could regain a sense of power by surrounding their houses in witch marks, by performing counter magic and coaxing witches down their chimneys so they could burn her in their cooking pots.

In short, the witch was a significant Minotaur Opponent of early to mid 14th century Europe. As we can see from just this one example, the Minotaur Opponent is an extremely powerful storytelling technique, to the point where such stories can influence people’s real world beliefs.

The Minotaur layer of opposition continues to work so nicely in stories today because it both drives ‘regular’ people apart as well as uniting them together.

But we do need to remain wary of our tendency to translate this Minotaur Opposition into real life, especially with another climate crisis hanging over our heads.

In everyday English we now use the word ‘bogeyman’ to describe a monster who is not the real monster.

CAN A CHARACTER BE THEIR OWN WORST ENEMY?

You might be asking yourself at this point, can the main character be ‘their own worst enemy’?

The antagonist is … the thing or person the protagonist must vanquish to achieve their goal. The detective and ‘monster’ templates illustrate this well, but antagonism can manifest itself in many different ways — most interestingly when it lies within the protagonist. Cowardice, drunkenness, lack of self-esteem — all will serve as internal obstacles that prevent a character reaching fulfilment.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

However, if your main character’s ONLY opponent is their own self, you’re in for a tough job. Sure — great stories can be created in which the main character is their own worst enemy. An excellent example is Larry McMurtry’s Hud, from his novel Horseman, Pass By. That said, McMurtry knew that in order to show the audience that the character of Hud is his own worst enemy he had to do it via conflict with other characters. He couldn’t just put him on a farm alone. Even in The Martian by Andy Weir, the story was improved with the addition of other people — the base back on Earth, and the backstory which included the other astronauts. The Martian environment is plenty oppositional enough, but doesn’t make for the best story.

In very short stories, such as children’s picture books, a main character can be their own worst enemy and the story works well. Two examples are After The Fall by Dan Santat (recent) and The Chicken Book by Garth Williams (classic).

Where the character is their own worst enemy, that part goes under the ‘psychological shortcoming’/’moral shortcoming’ banner, not under this one.

If you are writing a story in which the main character’s biggest enemy is themselves, you are writing what’s commonly known as a ‘Man vs. Self’ story. This article at Now Novel has some specific pointers on how to do it.

OPPONENTS AND GENRE

The opponent will depend on the genre/type of story you’re writing.

In the simple detective story they’re catalysed by the murder; in the medical drama the patient. […] In the simple thriller form the antagonist is marked out by their desire to control and dominate the lives of others. They don’t follow the moral codes of the community; more often than not they’re an embodiment of selfishness. They are also, historically, often marked by physical or mental deformity. Le Chiffre’s maladjusted tear duct in the film of Casino Royale is the modern equivalent of Dr No’s missing hands or Scaramanga’s third nipple in the Man With The Golden Gun.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

Since ‘nature’ makes an uninteresting opponent, even when the opponent is plenty strong enough the writers will concoct human antagonists. In Twister the hurricane is the main opposing force, but none of the characters are getting on with each other, either.

If there’s a killer or an evil mastermind bent on planetary domination then they are, obviously, the antagonists [often called ‘villains’]; the patient may not behave antagonistically, but they effectively embody the illness that will be the true enemy in the drama. The antagonist is thus the thing or person the protagonist must vanquish to achieve their goal.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

RULES OF FICTIONAL OPPONENTS

They call it a conflict and with my limited grasp of the English language, the prefix “con-” is bad. Why can’t we just have a “flict”?

EJ (@cottone120) November 29, 2019

An opponent is not necessarily an enemy.

I always felt like you had to be important to have enemies. Example: Historically, Germany has had more enemies than Luxembourg. Margo Roth Spiegelman was Germany. And Great Britain. And the United States. And tsarist Russia. Me, I’m Luxembourg. Just sitting around, tending sheep, and yodelling.

John Green, from Paper Towns

The opponent is the character who wants to prevent the main character from reaching her goal.

The relationship between opponent/main character is the most important in the story.

The best opponent is the necessary one. The opponent is the character who is best able to attack the great shortcoming of your main character.

The main character will either overcome that shortcoming or be destroyed.

Opponents and mystery are closely related because a mysterious opponent is more difficult to defeat. In average stories, the main character’s only task is to defeat the opponent. In good stories the main character has to:

- Uncover the opponent and

- then defeat them.

In thrillers and mysteries there has to be some kind of mystery set up to compensate for the missing opponent (who is there, but behind the scenes). Detective stories purposely hide their opponents until the end. Until then, the audience needs something to replace the ongoing conflict between main character and opponent. In this kind of story you introduce a mystery at about the time you would normally introduce the main opponent.

It pleases contemporary filmmakers and thus audiences to think they are much more sophisticated than this, but cruelty continues to be the mark of villains, the thing that lets the audience know who they are supposed to be against. […] Innocence is central to determining whether the behaviour is cruel or not.

Howard Suber

Other characters [apart from the main character] in a story can act heroically — not just the designated main character. Even villains and baddies can very effectively portray heroic qualities. Every rounded character should manifest a touch of each archetype (The Shadow In The Hero).

The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler

Frequently the main character and villain’s actions look very much alike. It’s what these actions are for that determines whether we think of the character as being obsessed or committed.

The Power Of Film, Howard Suber

It’s often said that the best cops would make the best criminals — by chance they’re working on the right side of the law. Crime drama makes the most of this. In The Wire, Jimmy McNulty is a good cop because he has an intuitive understanding of what motivates the criminals he’s working with. The audience sees Jimmy himself go against the rules and resisting the hierarchy that exists within the police force.

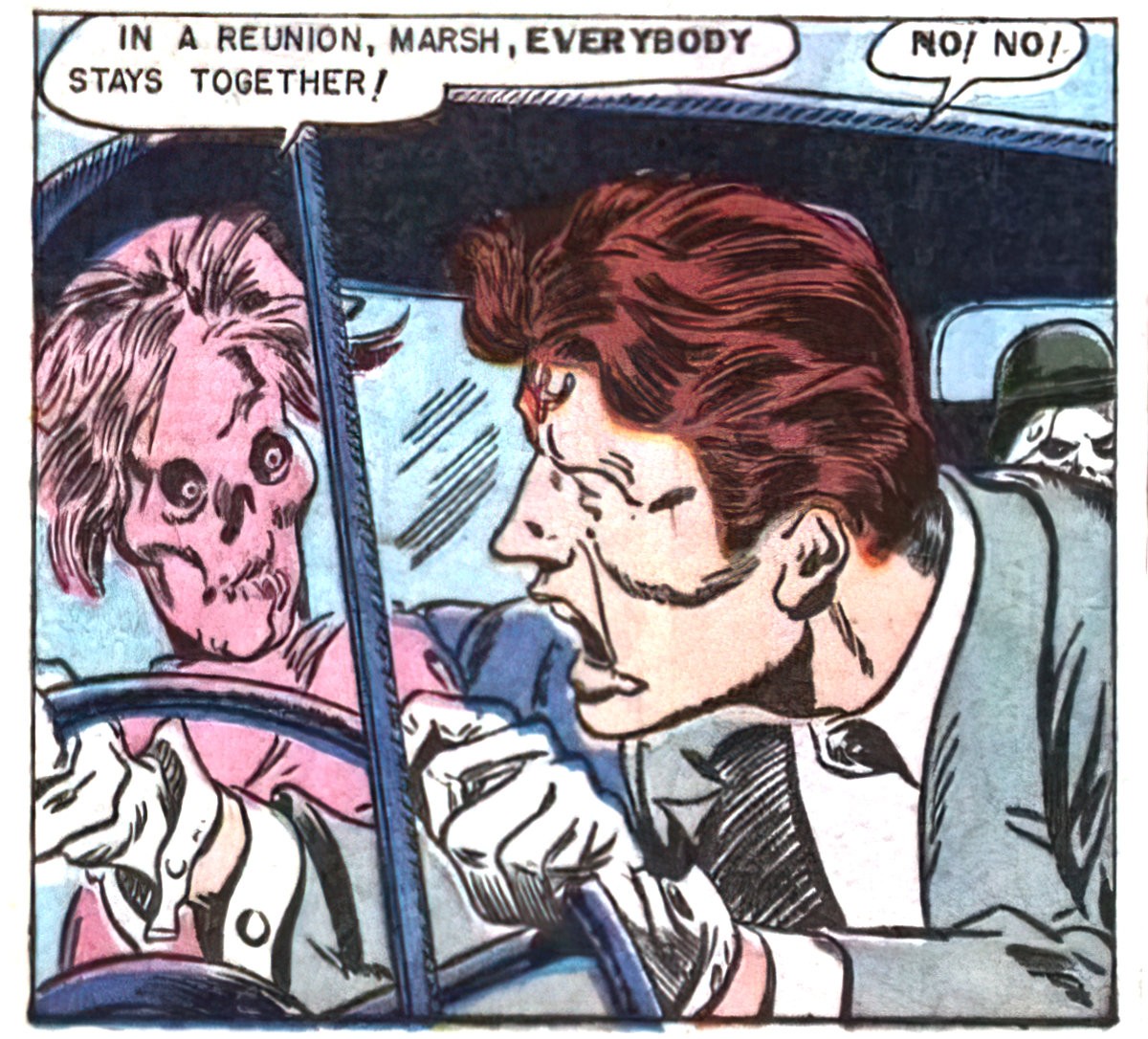

Keep the opponent AND main character TOGETHER

This goes against common sense, because when two people don’t like each other they tend to go in opposite directions. But if this happens in a story, the writer has great difficulty building conflict. The trick is to find a natural reason for the main character and opponent to stay in the same place during the course of the story.

In Pride and Prejudice, Lizzie is forced to spend time with Darcy when Mrs Bennett forces Jane to ride to Bingley’s mansion. There, she catches cold, and Lizzie must go and see her. Darcy happens to be there and flirting takes place after dinner, in which social convention dictates they share the same room.

The antagonist opposes the protagonist not just once but throughout. In this way the antagonist helps define the protagonist in the same way you invoke a shape by colouring in everything but that shape. Note that the antagonist needn’t be another character — it traditionally is, yes, but any persistent conflict can be truly antagonistic. A looming house foreclosure, a cancer diagnosis, a tornado made of biting squirrels.

Chuck Wendig

In memorable movies…the strongest guy around is not likely to be the main character.

Howard Suber

OPPONENT AND MAIN CHARACTER ARE EQUALLY POWERFUL

VILLAINS

A villain is a subcategory of opponent. An opponent equals anyone or anything that stands in the way of your main character getting what they want. A villain is ethically and morally bad. Villains tend to be power hungry, lazy, abusive, greedy — all of the seven deadly sins.

The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.

Alfred Hitchcock

In traditional main character stories there are ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ (better known to adults as main characters and adversaries, or protagonists and antagonists). The activities of the main characters are sanctioned by society whereas the activities of the adversaries are considered wrong. Apart from pickpockets/thieves, the following groups tend to be depicted as adversaries in stories, because their ways of making a living undermine our perceptions of how decent society works. For example:

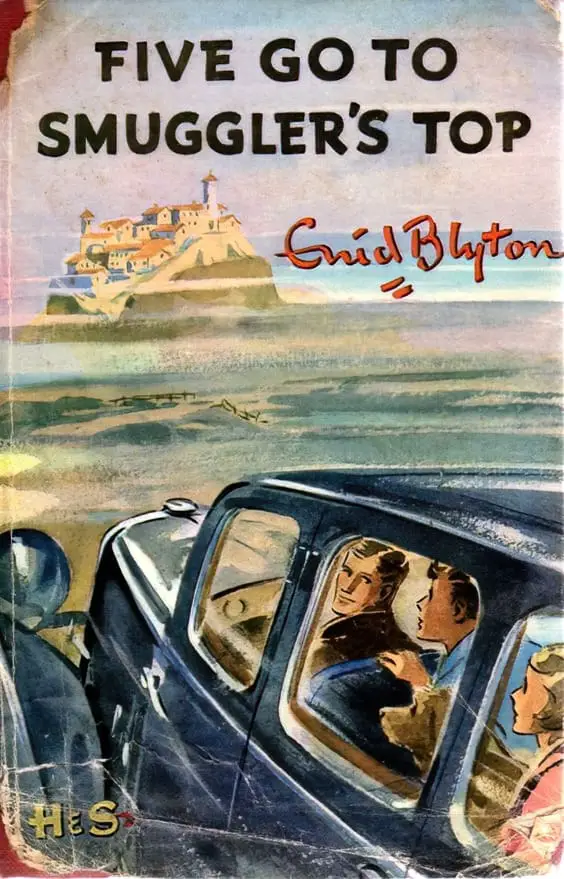

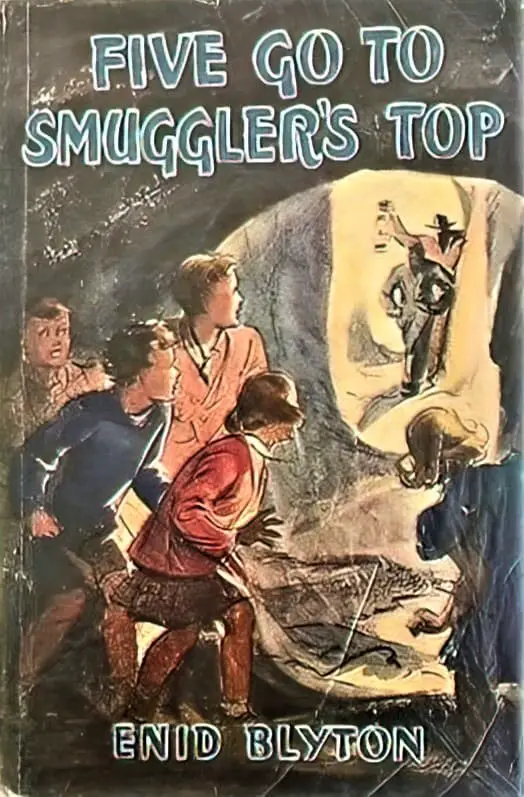

- Smugglers — e.g. from a Famous Five novel

- Pirates — in picture books pirates as just as often the sympathetic viewpoint characters, which is weird given that in real life they are criminals

- Gypsies — also oft-utilised by writers from the First Golden Age of children’s literature e.g. Enid Blyton

- Highwaymen — Julia Donaldson’s Highway Rat is a picture book example.

- Wolves — Since wolves became an endangered species recent stories often turn the wolf into the victimised character.

- Foxes — Straight out of Aesop, foxes are like wolves only more wily

- Witches and other supernatural, folkloric creatures

Note that only two genres require a villain: mystery and thriller.

I try to create sympathy for my characters, then turn the monsters loose.

Stephen King

What puzzled me about villains was why, when they were masquerading as respectable citizens, their essential no-goodness wasn’t as obvious to people on the screen as it was to me in the stalls. How could Pinnochio be so stupid as to be led astray by the patently wicked Fox, or Snow White not know the Queen was up to no good? Had the Queen been flesh and blood and not a cartoon she might well have been played by Joan Crawford, who was always something of an enigma to me. I never liked her, and with her gaunt face, protruding eyes and instinct for melodrama she seemed the embodiment of evil, yet she was often cast in the role of heroine… Claude Rains was another puzzle. He was determinedly silky and seldom unsmiling, sure signs that he was a baddy, though not always. […] Banal though the general fun of films was, I learned, as one learned in fairy stories, about good and evil and how to spot them: the good where one would expect only degradation and squalor, and treachery and cowardice to be traced in the haunts of respectability. I learned about the occasional kindness of villains an the regular intransigence of saints but the abiding lesson had to do with the perils of prominence… Films taught you to be happy that you were ordinary.

Alan Bennett, from Untold Stories

People have a need to believe that bad things are done by bad people. And what is bad? Isn’t this defined as anything outside the common good, which is further defined as whatever the majority see as good? Why must the villain wear a black hat? Because if he didn’t, how would we know he was the villain?

Stephen Dobyn, from The Church Of Dead Girls

Charlie Jane Anders has some counter advice to a popular chestnut given to writers when creating villains, and I agree it’s time we need to say this:

One piece of writing advice I hear a lot is, “Nobody thinks they’re the bad guy. Everyone’s the hero in their own story.” Which is true, I guess. But I worry people understand this to mean “every character needs to have sympathetic, relatable motivations.” Which is NOT true.

There’s no shortage of people in the world who enjoy being cruel to people who are more vulnerable than they are. There’s plenty of people who think of the world purely in terms of dominance and power, or who pride themselves on being able to “do what has to be done.”

In my writing, I’m very interested in the problem of evil, and a lot of my stuff features well-meaning people who make horrible choices. But I’m not interested in excusing destructive behaviour, or necessarily sympathizing with it. Not all villains have to be lovable/relatable.

George RR Martin is very good at showing the internal monologue of people who do monstrous things, without softening them at all. Meanwhile, Shakespeare famously has one of his villains declare his undying hatred, “yet I know not why.” Not everybody is equally introspective.

Bottom line: evil is real. Cruelty is real. We have to grapple with them in our fiction, whether it’s a lighthearted romp or a grimdark adventure. And I don’t feel like sympathetic evil is always the right choice, depending on the story. /END

@charliejane

Charlie Jane Anders also advises writers to avoid the following when creating villains:

- Villain who are passive until the last few minutes of the story

- Inversely, villains who are super powerful all through the story, then implausibly start making mistakes right at the end (allowing the hero to win)

- Villains whose behaviour make no sense, doing whatever the story requires them to do in the moment.

I would add that commercially successful blockbuster movies don’t go out of their way to avoid those traps. The clown of I.T. is number three to a tee, but that is one successful franchise.

Related Links On Villains

- A new study reveals that, given a choice, people will stare longer at the faces of people they’ve heard bad things about.

- Top 10 Sympathetic Supervillains from List Verse

- 50 Great Villains In Literature from Flavorwire

- 9 Villains In Literature And Film, And How To Make Yours Better from The Write Practice;

- Almost-Great Bad Guys For Almost-Adult Readers from Literacy Journal

- Writing Beyond The Good/Bad Dichotomy from LitReactor

- Wait, that’s not a super villain! from Free Thought Blogs

- The Women On House Of Cards Are Just As Evil As The Men, a refreshing change reported by Jezebel

- Gendering Monsters from Breaking The Glass Slipper podcast

- The Best Villains In Children’s Books from Imagination Soup

- Psychology Uncovers Sex Appeal of Dark Personalities from Scientific American

- Screw Princesses — Disney Villains Are the Real Role Models

- The Faceless Villain: What to do When Your Bad Guy Isn’t a Person from The Other Side Of The Story

- The 10 Most Badass Women In Fantasy Literature from Barnes and Noble

- Movie Villains Done Right, a YouTube video from Glowing Screens takes a deep dive into The Joker from the Batman movies. The Joker and Batman are similar characters, but on morally opposite sides. (This is known as Shadow In The Hero.) They also talk about Hal from 2001, A Space Odyssey, the epitome of cold and logical. Importantly, Hal thinks he’s the good guy, which is common to villains. Nothing is more scary than being able to see the villain’s point of view.

- Creating The Ultimate Antagonist is a YouTube video from Lessons From The Screenplay, also looking at The Joker from Batman. Everyone agrees that Heath Ledger played the Joker the best.

- A Reddit Thread started by someone who created a taxonomy of villains.

- Digital Spy thinks there haven’t been any decent villains in movies for the last ten years (counting back from 2018).

VILLAINS AND GENDER

Villains are traditionally gendered male. A female villain is seen as just that — a ‘female’ villain. Her gender is something extra. This means that decision makers can decide at any time that we’ve at ‘peak female villainy’.

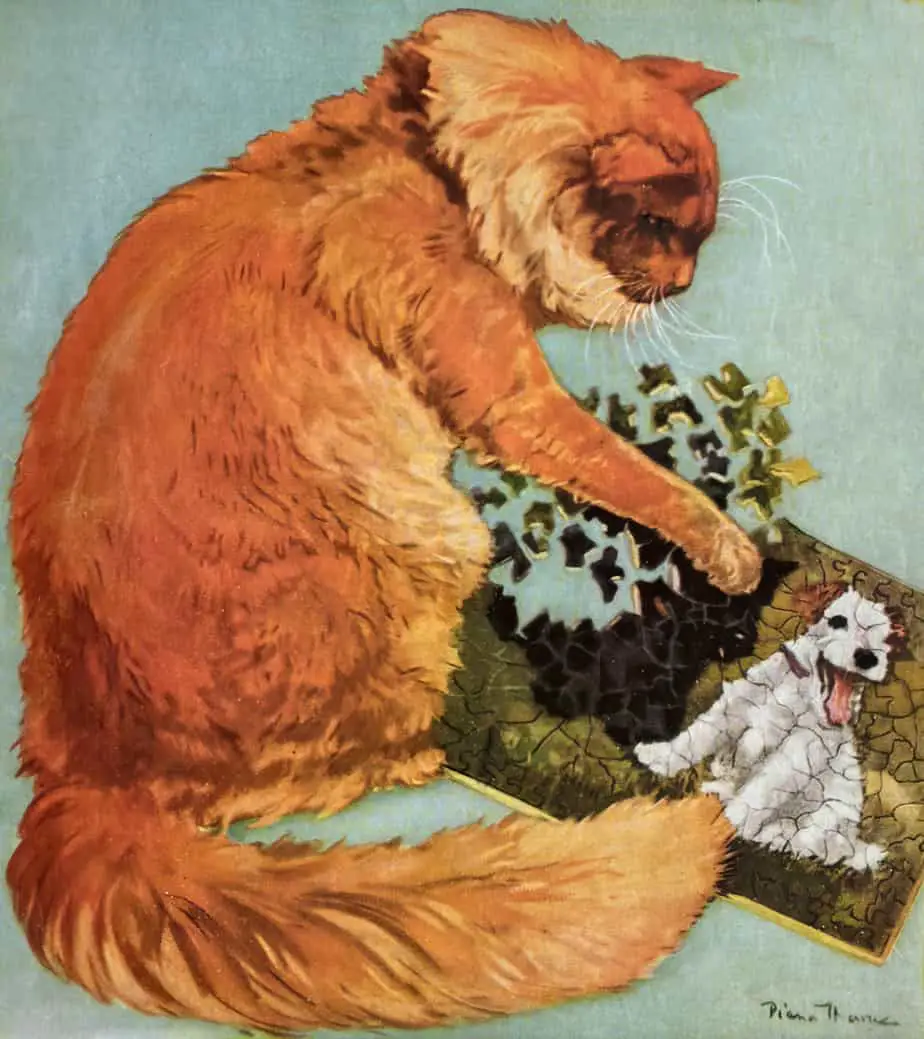

CHAOS RATHER THAN VILLAINY

Often it is chaos, rather than evil, that is the enemy.

Howard Suber

You’ll find those attributes (chaos and evil) are embodied in people, or — especially in children’s literature — as people stand-ins such as talking animals.

In other words, the opponent isn’t necessarily of evil intent. The opponent isn’t necessarily a ‘villain’. Case in point, the frenemy opponent. Someone who pretends they’re on your side, but they are not.

THE FRENEMY OPPONENT

Sometimes the opponent tries to fake as an ally to the main character but their wishes are at odds with the main character’s. This character exists partly to showcase a contrasting value system, for example, the main character is loyal, the frenemy is disloyal.

The frenemy opponent relies on a storytelling technique involving a mask. The mask of ‘friendship/mentorship’ will come off before the story is over.

OPPOSITION DOES NOT EQUAL THE APPEARANCE OF OPPOSITION

THORN OPPONENTS

‘The thorn in the side’ is a low-level opponent who doesn’t really have the power to fully stand in the main character’s way, and who can even make the audience side more fully with the designated main character.

Examples of thorns:

- The annoying kids in children’s book casts, such as Fregley in Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

- In a detective story it’s that member of the public who wants to get in on drama and offers theories and speculation as fact to the detective trying to solve the case.

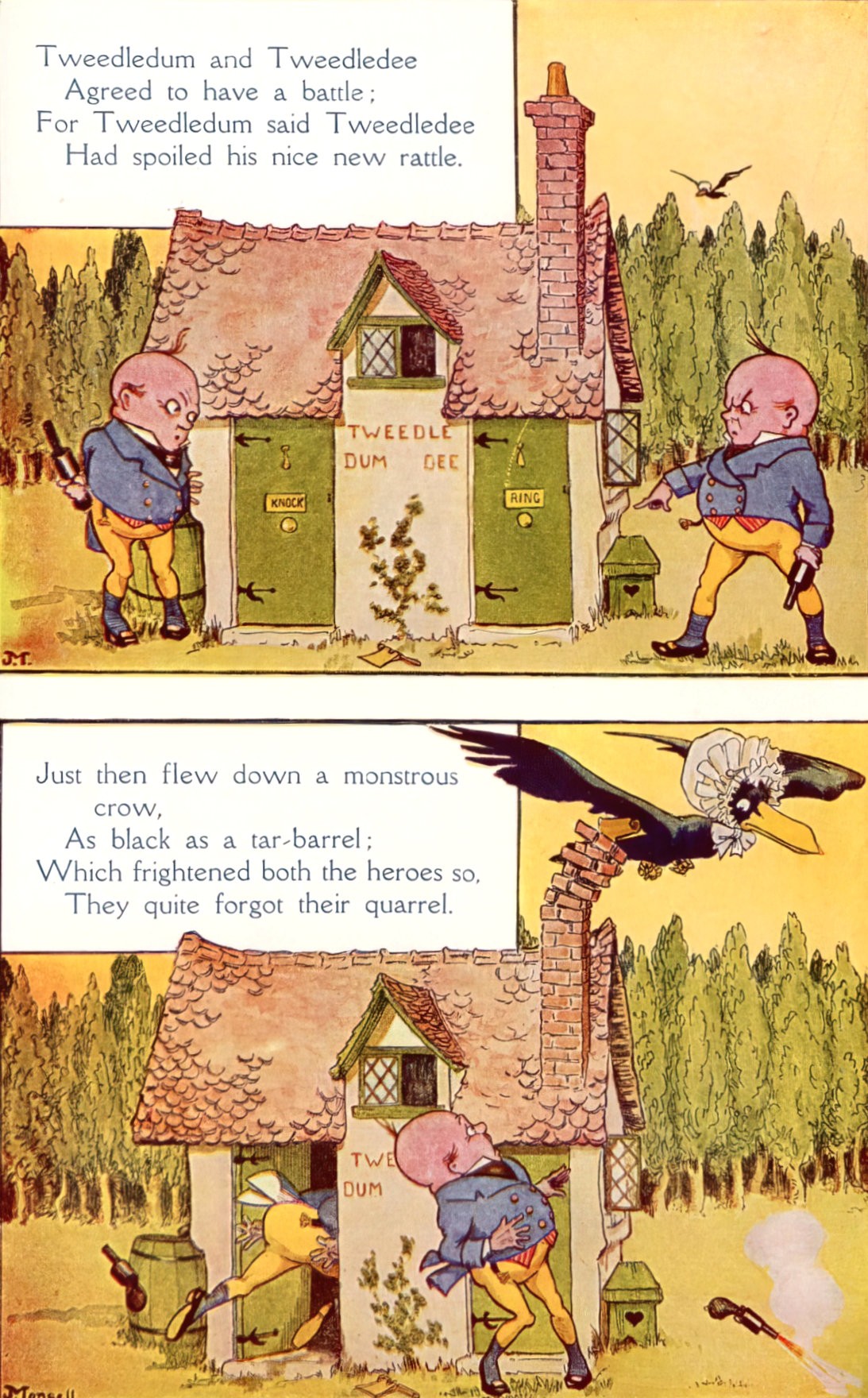

OPPOSITION CONVEYED IN PICTURE BOOKS

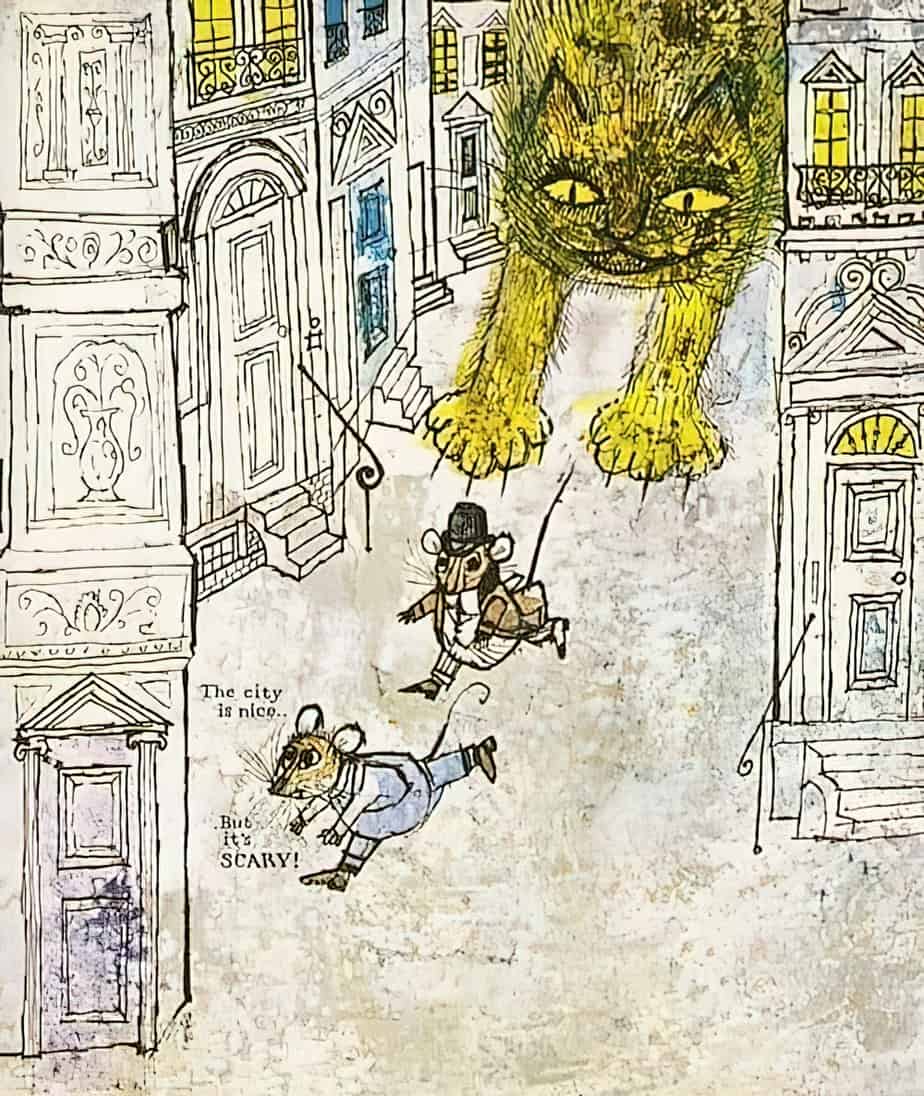

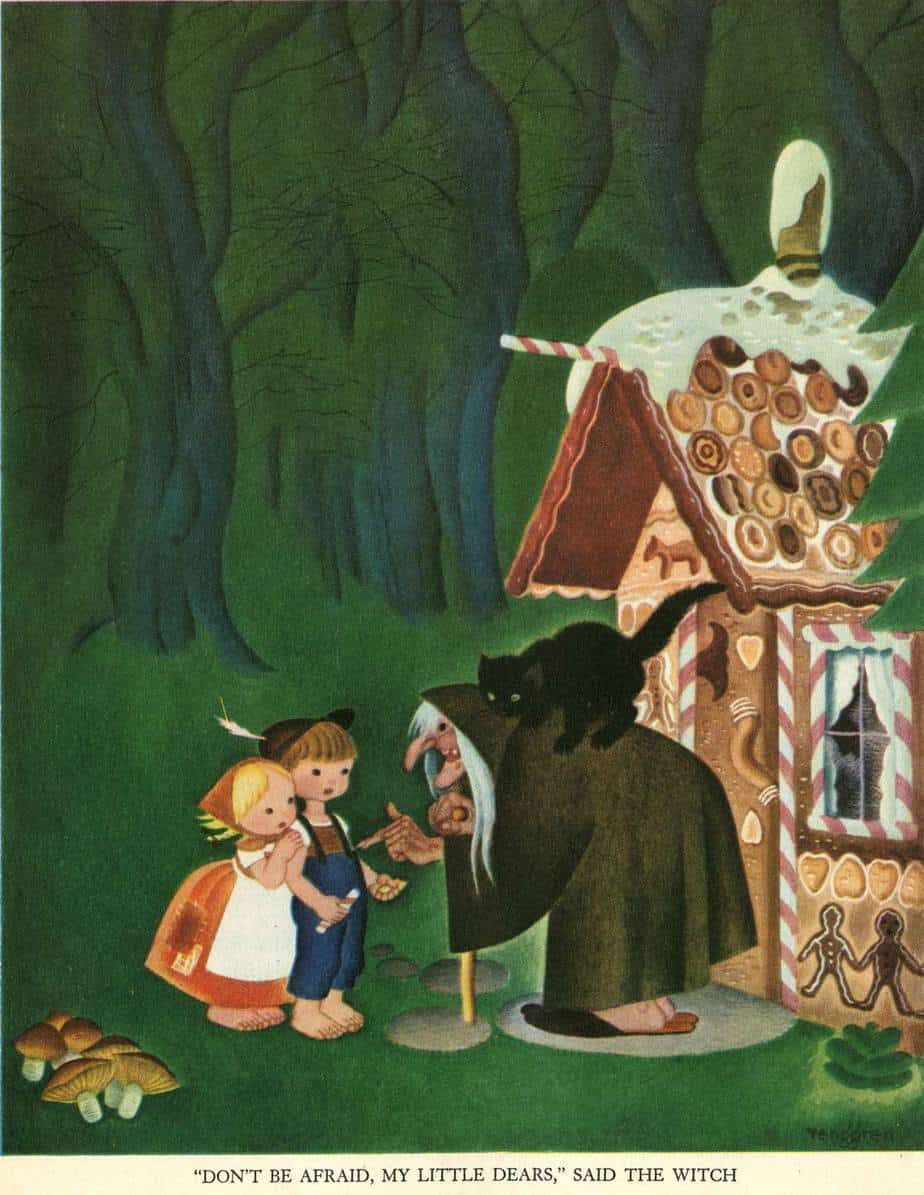

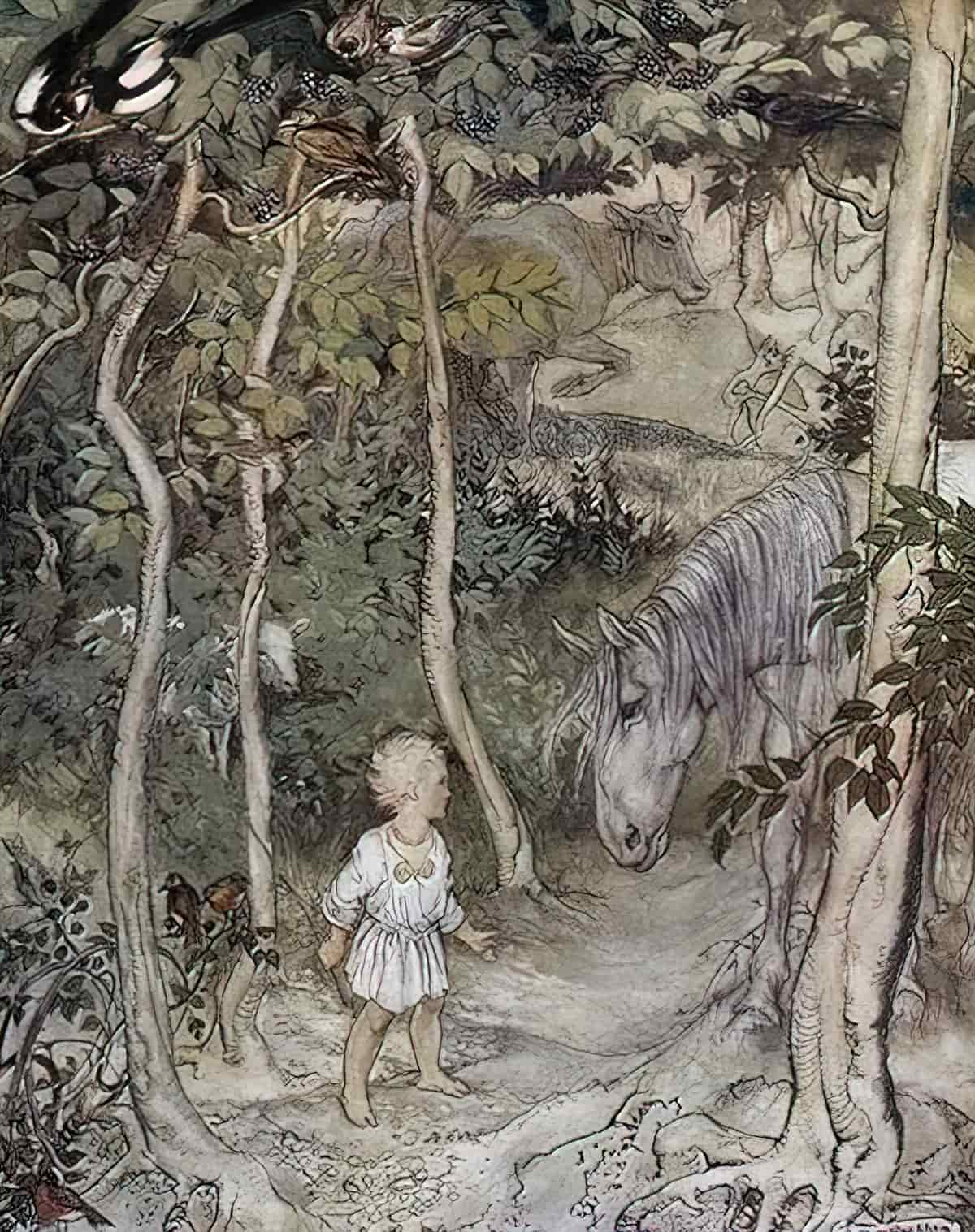

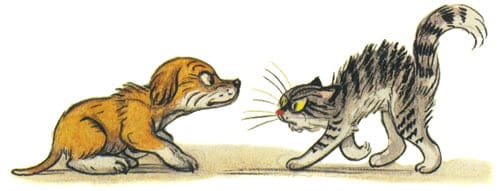

In an illustrated work, there will be an image in which the main character comes face to face with the opposition.

Take a look at the Hansel and Gretel illustrations below, by Gustaf Tenngren. Hansel and Gretel move through the book from left to right, absolutely typical for Western style literature. The witch is their opponent so she faces the other way.

But! When fortune is reversed and the children step forward to win the day, Tenngren reverses the direction of the witch. The children continue to face ‘forward’. Their mythic journey into the woods has not been stymied by that pesky witch.

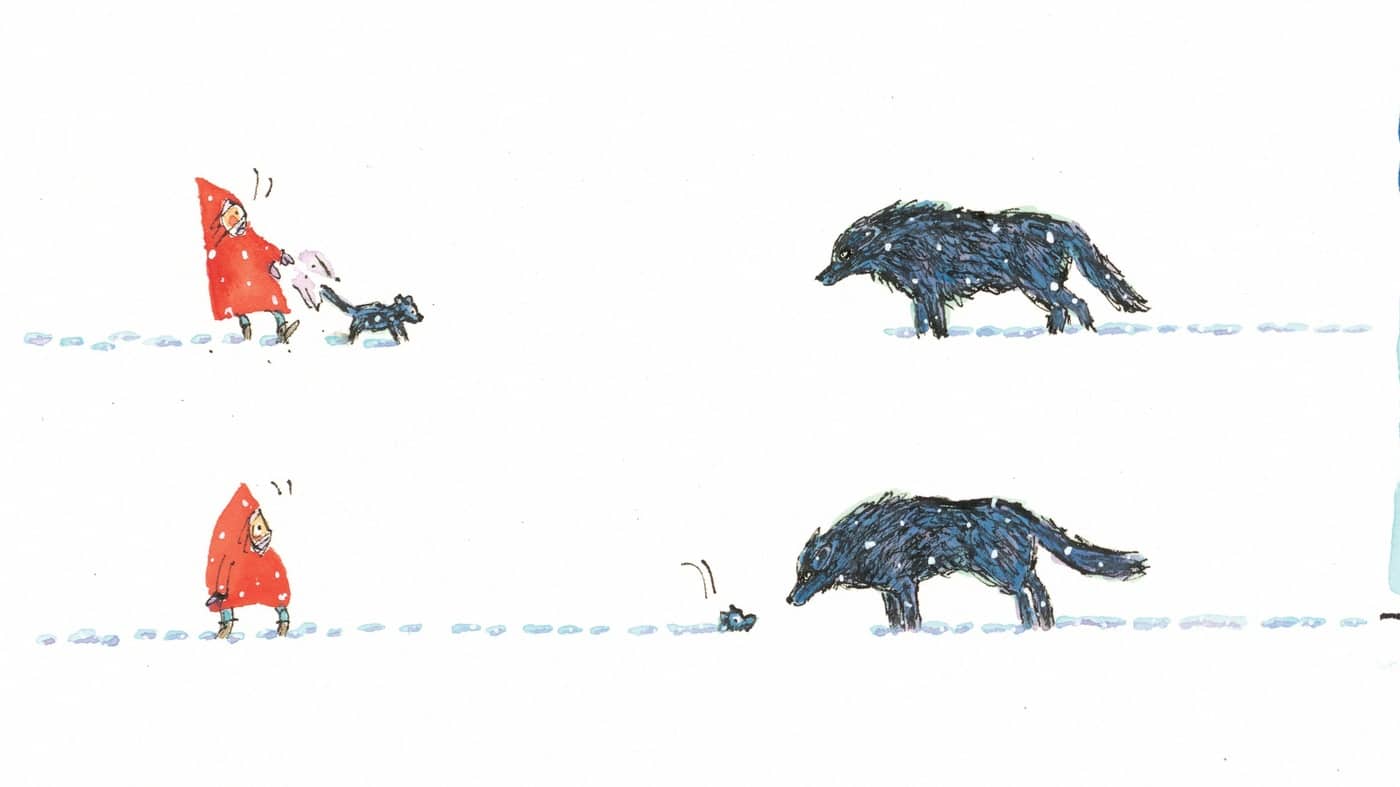

Below are some examples from Little Red Riding Hood.

Matthew Cordell’s Wolf In The Snow is a much more recent revisioning of Little Red Riding Hood, demonstrating that this layout is still very much used, because it is effective.

Gila Monsters Meet You At The Airport is an interesting example because these opponents exist to give the reader a parallactic view of two places, using two very different points of view. The effect is to help young readers challenge their own preconceptions.

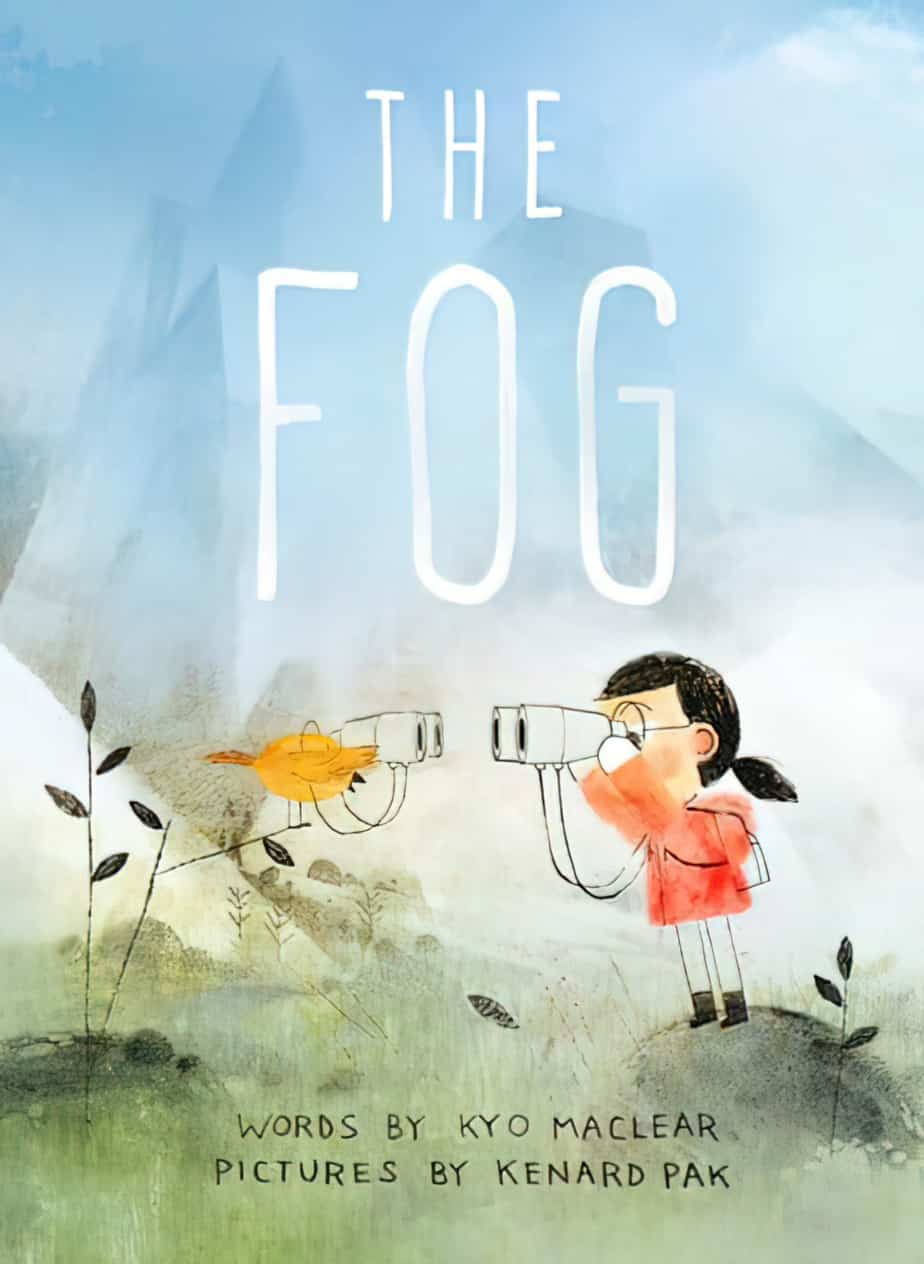

In The Fog, the scene where humanity really sees the importance of nature is so central to the story that it’s used for the front cover.

The scene where the mouse meets the Gruffalo is another example, but illustrator Axel Scheffler has made it look 3D with inclusion of the tapering path.

And here is an example from Blueberries For Sal.

FURTHER READING

Popular film culture has been using facial injury as a shorthand for evil for so long that many filmmakers no longer treat scars as injuries, but as decorative features.

Despite appearances, not all people with scarred faces are movie villains

Header painting: Henry Gillard Glindoni – The Tiff