Coming-of-age is a type of story in which a young person becomes an adult, or heads in that direction.

There are many children’s stories (or stories about children) about a child losing their innocence. When that character is a bit older (adolescent) then it’s called a coming-of-age story.

Sometimes people think they know you. They know a few facts about you, and they piece you together in a way that makes sense to them. And if you don’t know yourself very well, you might even believe that they are right. But the truth is, that isn’t you. That isn’t you at all.

Leila Sales

Horny Teenager Movies

I have a friend who swears she can’t stand any kind of coming-of-age story. Her definition is a little narrower than mine. She’s thinking of the genre typified by the likes of American Pie.

In one sense, all memorable stories are coming-of-age stories, if what we mean by the term is a story about someone who moves from one stage of development to a more advanced one. […] Films explicitly labelled a “coming-of-age story,” however, are often about nothing more than someone’s becoming aware of sex.

Howard Suber

Film critic Robert Ebert had a separate phrase to describe these movies:

Horny Teenager Movie: Any film primarily concerned with teenage sexual hungers, usually male. Replaced, to a degree, by Dead Teenager Movies (q.v.), but always popular with middle-age movie executives, who like to explain to their 17-year-old stars why the logic of the dramatic situation and the teachings of Strasberg and Stanislavsky require them to remove their brassieres.

Ebert’s Guide to Practical Filmgoing: A Glossary of Terms for the Cinema of the ’80s

See also: In Coming-of-Middle-Age Stories, Adults Grow Up, Too, an archived article at The New Yorker

IDEOLOGY IN TYPICAL COMING-OF-AGE STORIES FOR YOUNG ADULTS

The following appears to be the common message of coming-of-age stories for a young adult audience:

You’re not going to die. Here’s the white-hot truth: if you go bankrupt, you’ll still be okay. If you lose the gig, the lover, the house, you’ll still be okay. If you sing off-key, get beat by the competition, have your heart shattered, get fired… it’s not going to kill you. Ask anyone who’s been through it.

Danielle LaPorte, Canadian author

Features of a Coming-of-age Story

- Coming-of-age stories for adult audiences are often set in the past. Coming-of-age stories for young adult audiences are more often set in the present.

- What’s the upper age limit for a coming-of-age main character? There doesn’t seem to be a limit in years, but the main character remains childlike in some way. An example of a coming-of-age character in her late twenties is Ruth in I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore.

- A psychoanalytic reading of a coming-of-age story done badly might “pathologize” childhood. A storyteller might describe childhood as a symptom to be overcome in the journey to mature adulthood. This is why in a lot of coming-of-age tales, the child (adolescent) grows a bit, but at the end demonstrates that they haven’t given up on childhood completely. We see it, for instance, in Monster House. DJ decides to go trick-or-treating after all, despite eschewing all boyish things at the beginning of the story.

Coming-of-age Arcs Happen In Stories About Grown-Ass Adults

Potential has a shelf life.

Margaret Atwood

We find ‘coming-of-age’ arcs in all kinds of stories. Arctic Dreams is a travel adventure, but the following paragraph is all about coming-of-age. However, adults are learning different things. Coming-of-age stories about teenagers are often about the realisation of death, specifically the life stage Heidegger called Being-toward-death.

THE EXAMPLE OF ARCTIC DREAMS

Barry Lopez explores in Arctic Dreams the specifically adult arc of learning to live with paradox:

How is one to live a moral and compassionate existence when one is fully aware of the blood, the horror inherent in life, when one finds darkness not only in one’s culture but within oneself? If there is a stage at which an individual life becomes truly adult, it must be when one grasps the irony in its unfolding and accepts responsibility for a life lived in the midst of such paradox. One must live in the middle of contradiction, because if all contradiction were eliminated at once life would collapse. There are simply no answers to some of the great pressing questions. You continue to live them out, making your life a worthy expression of leaning into the light.

Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (1986)

This bestselling, groundbreaking exploration of the Far North is a classic of natural history, anthropology, and travel writing.

The Arctic is a perilous place. Only a few species of wild animals can survive its harsh climate. In this modern classic, Barry Lopez explores the many-faceted wonders of the Far North: its strangely stunted forest, its mesmerizing aurora borealis, its frozen seas. Musk oxen, polar bears, narwhal, and other exotic beasts of the region come alive through Lopez’s passionate and nuanced observations.

And, as he examines the history and culture of the indigenous people, along with parallel narratives of intrepid, often underprepared and subsequently doomed polar explorers, Lopez drives to the heart of why the austere and formidable Arctic is also a constant source of breathtaking beauty, beguilement, and wonder.

What Is A Bildungsroman?

My friend who can’t stand coming-of-age stories is probably fine with the bildungsroman. (The plural, by the way, is bildungsromane.) The German translates to ’novel of formation’ or ‘novel of education’.

The bildungsroman is a specific subgenre of coming-of-age story. It focuses on the main character’s psychological and moral growth. Character change is extremely important.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BILDUNGSROMANE

Originally ‘bildungsroman’ meant a romantic story but we’ve narrowed the definition right down. The word now refers to a type of story which follows a character as they grow from adolescence into adulthood.

The genre evolved from folklore tales of a dunce or youngest son going out in the world to seek his fortune.

Young adult novels evolved from the bildungsroman.

HOW TO SPOT A BILDUNGSROMAN

Usually in the beginning of the story there is an emotional loss which makes the main character leave on their journey.

The genre often features a main conflict between the main character and society. Typically, the values of society are gradually accepted by the main character and they, in turn, are ultimately accepted into society. The main character’s mistakes and disappointments are over. In some works, the main character is able to reach out and help others after having achieved maturity.

Harry Potter is very much a bildungsroman. Pride and Prejudice probably isn’t because it only takes place over the course of a single year. But Jane Austen’s classic does have a significant character arc. In Twilight, we follow Bella Swan from late adolescence into adulthood. The Twilight series is unambiguously a bildungsroman.

THE BILDUNGSROMAN AND ROMANCE

The goal is maturity. The main character achieves it gradually and with difficulty.

This makes the bildungsromane inherently Romantic. It has an optimistic ending which affirms the main character’s entry into adulthood.

Another Romantic idea: belief in the individual. Romanticism is all about the individual taking responsibility for themselves, living their own best life, finding one’s own place within society and so on.

New Adult Novels

In the early 2000s, a new category of literature looked fairly likely to take off: New Adult. However, New Adult stories didn’t really gain popularity. New adult stories tend to be about young people leaving home — around college age. But others have said New Adult isn’t about age so much as the ‘coming-of-ageness’ of it. New Adult was the name given to adult fiction which emphasised the coming-of-age aspect. People can experience a life-transforming development at any age. Coming-of-age experiences are not limited to youth.

ISN’T EVERY STORY ABOUT CHARACTER CHANGE?

In its broadest sense, every story is a bildungsroman, right down to toddlers who star in picture books. Doesn’t every character grow, outside those in series fiction (which Maria Nikolajeva calls ‘paraliterature’)? Some sort of character arc is a requirement for a full and complete narrative.

Some academics prefer to narrow the term to a more useful definition: Bildungsromane star characters who mature from childhood to adulthood. This, at least, is useful.

FROM CONFUSION TO CLARITY

The guy who came up with the word (Wilhelm Dilthey, 1870) meant it to refer to stories in which:

- There is a cultural goal

- Which is the complete unfolding of all the natural qualities

- Then there’s a clear path toward that goal

By this definition, the bildungsroman is a direct path from confusion to clarity.

BUCKLEY’S DEFINITION

Here’s another definition of the bildungsroman, by Jerome Buckley.

- A sensitive child grows up in a rural setting feeling confined by his entire family (but especially by the father), and the father can’t understand the boy’s imaginative life (because these stories are traditionally about boys).

- School proves restrictive so the boy leaves home to go into an urban centre.

- He will have at least two romantic experiences.

- One of those has the potential to corrupt him and the other has the potential to purify him. (Can you see how those sexist Betty and Veronica tropes are inherent to such stories? They divide all women into a binary of either wholesome or whore, marriageable or unmarriageable, Virgin or Madonna, and Mammy or Jezebel for Black women.)

- The young man’s initiation is complete when he does a bunch of soul-searching then triumphs over the trials he faces with his parents and/or money and/or women and accepts his own capacity for work and for love.

Which is probably a bit too specific. Also, in the traditional bildungsroman, the main character is setting out to deliberately become independent. He’s trying to cultivate himself via novel experience. These are quest narratives. The quest is ‘to find oneself and grow up’.

But have you heard of the Entwicklungsroman?

- Another type of story about the maturation process.

- This is a very broad category in which an adolescent character grows (some). It’s subtly different from a bildungsroman because in the bildungsroman, the adolescent matures to adulthood.

- Entwicklungsromane are novels of growth or development, whereas bildungsromane are coming-of-age novels, sometimes referred to as ‘apprenticeship novels’. (See also: School And Children’s Literature)

Entwicklungsromane or Bildungsromane?

I suspect many young adult novels are more Entwicklungsromane than Bildungsromane. A young adult character rarely seems like an adult at the end of the story. More likely they’ve overcome one particular problem but still have a lot of growing to do before they can exist in the world independently and happily. Then again, when does one become an adult?

Coming-of-age Stories and Horror

There’s an entrenched idea that children are ‘unfinished’ in relation to adults, who have reached ‘telos’. (Telos means ‘end’ in Greek, and refers to an ultimate object or aim.) Some stories — especially horror stories — subvert this idea of the finished/unfinished adult/child dichotomy by, for example, taking something from childhood then pushing it into the ostensibly realist adult world. (For a list of contemporary examples see this post.)

When children can see things adults can’t, that boundary between adulthood and childhood disappears. We realise it was never there in the first place. When adult and child worlds collide, this feels uncanny and unsettling.

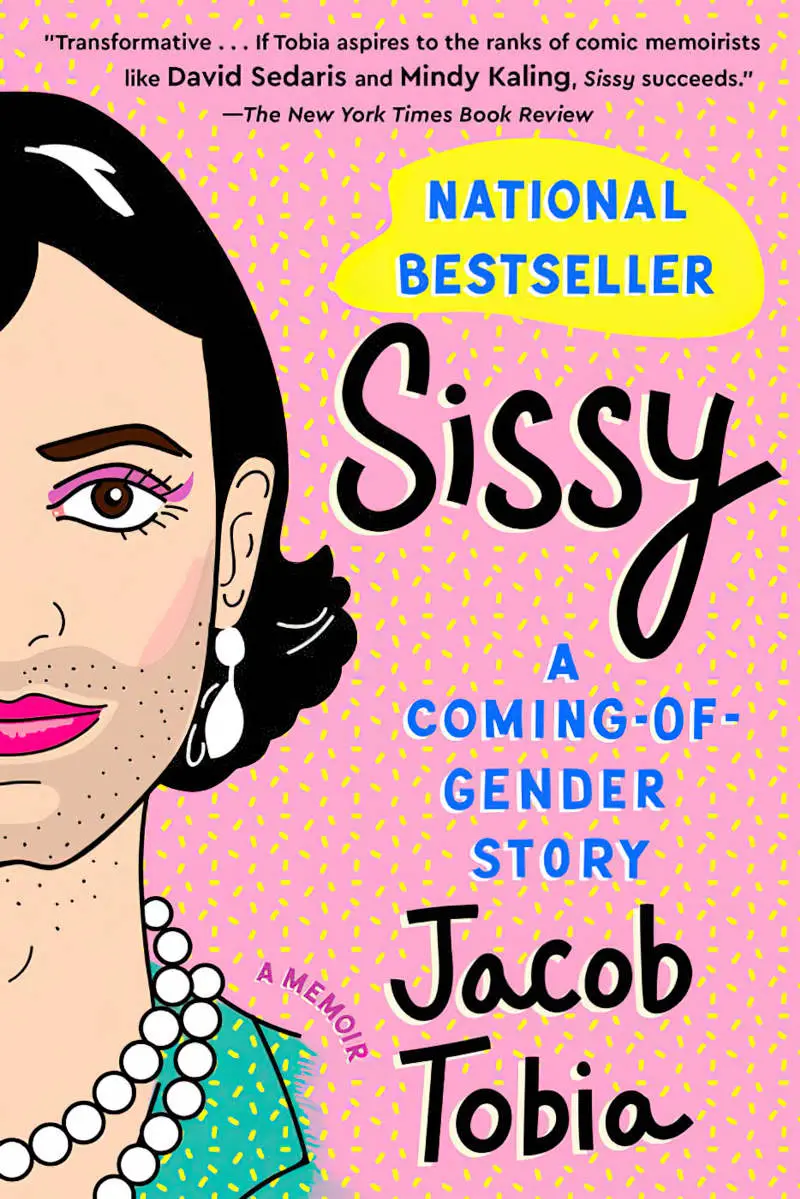

Bildungsromane and Gender Diversity

There’s no room in the traditional definition of Bildungsromane for female characters. If a story stars a young woman, it’s probably an Entwicklungsroman. Paraphrasing Annis Pratt, in Archetypal Patterns In Women’s Fiction, most authors throughout the history of literature consider growing up female as a choice between:

- auxiliary slash secondary personhood OR

- sacrificial victimisation slash madness and death

There’s no real psychological growth or maturity in stories which limit young women to these choices. See also my lengthy post about the Female Maturity Formula.

LYDDIE BY KATHERINE PATERSON AS CASE STUDY

That said, there are examples of female main characters who seem to fit the bildungsroman perfectly. Katherine Paterson’s Lyddie is one example.

She was no better than a slave, Lyddie thought. The debt-ridden farm had been let to neighbour, and she and her brother had been hired out. Was the end really near, as their mother had said when she fled with the babies after the hungry bear had broken into their Vermont farm house?

That winter of 1843, the two children had been left to fend for themselves. If their long-gone father would return and set things right. It is the promise of a new and better life that finally prompts Lyddie to journey to the mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts. As a factory girl, she will earn a wage—and be free. No matter that she has to live in a crowded boarding house, that the clatter of incessant looms is deafening, that the murky lint-filled air brings on fevers and wracking coughs. Despite the menacing overseer, Lyddie works long, exhausting hours to be able to pay off the debt and regain her beloved farm.

But does she jeopardize her job—and her family’s future—by being friends with the radical Diana and perhaps signing a petition for better conditions.

- Lyddie is emotionally orphaned by her father. Her mother is out of the picture, too.

- Though embarrassed about being illiterate she decides to journey from the family farm in Vermont. She eventually arrives in the mill town Lowell, Massachusetts.

- Co-workers Betsy and Diana educate her, in a straightforward literacy narrative.

- Lyddie has two sexualised encounters with men.

- The first is quite debasing. (The foreman harasses her.)

- The other is more like a purifying romance. (Lyddie’s neighbour wants to marry her because he loves her mind.)

- She returns to her home and recognises how much she has known.

- She decides to defer marrying Luke until she has graduated from Oberlin.

- Her initial reasons for leaving home have come from a self-conscious recognition that she needed to learn how to earn a place in the world.

- Her final decision is based on the epiphany that the only thing limiting her is her own self-image.

- She overcomes poverty, ignorance and personal pettiness. She learns to balance her own materialism with her love of others and love of learning.

Until very recently, female bildungsroman, or coming-of-age stories about girls,

Procrustean Motherhood: The Good Mother during Depression (1930s), War (1940s), and Prosperity (1950s)

invariably ended in this same manner: The main character married, and her narrative went blank. She lost dimension as she adopted the one-size-fits-all role of wife and mother. Her individuality turned into a monotonous story, indistinguishable from those of her neighbours.

How about the Künstlerroman?

Künstlerroman means “artist’s novel” in English. This is a narrative about an artist’s growth to maturity. Künstlerromane are typically about characters on the threshold of becoming a poet, musician or painter.

James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) is the tentpole example.

We might classify the Künstlerroman as a sub-category of Bildungsroman.

Further Examples of Coming-of-age Stories

THE BIG THREE NOVELS OF INFLUENCE

- Seventeenth Summer by Maureen Daly — First of the three big novels which define young adult literature.

- The Catcher In The Rye by J.D. Salinger — Second of the three big novels which define young adult literature.

- The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton — This is the third big novel to define young adult literature as we know it today. This book changed young adult literature forever. For starters, it was written by a teenager.

A SELECTION OF OTHERS

- The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

- The Wonder Years — an adolescent boy comes of age in 1960s America, an especially good setting for a coming-of-age series because that’s when America herself was going through some kind of ‘psychological growth’.

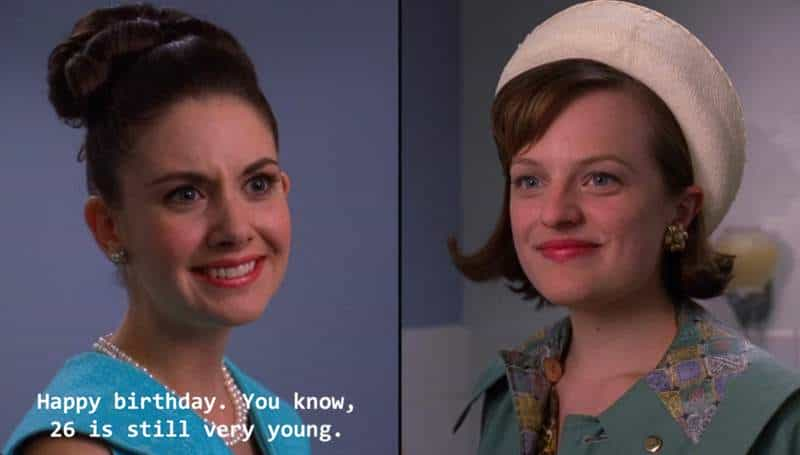

- Mad Men — in this American TV series a number of characters come of age. Peggy and Joan are the ‘secret main characters’, set against Don Draper who will never change much.

- Freaks and Geeks — a ‘Breaking Bad‘ kind of plot in which a good girl learns to break free of her nerdy reputation

- The Breakfast Club movie

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower — the book is far better than the film, and I’m not someone who always says that

- Malcolm In The Middle TV show

- Happy Days — the 1960s sit-com

- Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

- A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man — an example of Anglophone Bildungsroman

- Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence is about a sexual awakening.

- David Copperfield by Charles Dickens is another stand-out Anglophone example.

- The Mill In The Floss by George Eliot — There is no room in the original definition of Bildungsroman for female main characters, but this is definitely a coming-of-age example.

- What Maisie Knew by Henry James — Although Maisie is still very young she loses her childhood innocence.

- The Secret Life Of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd — Set in 1964, it’s a coming-of-age story about loss and betrayal.

- Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- About A Boy — in this case the main character is far too old to be living like a teenager and his young protégé is more emotionally aware than he is. This, of course, is the point of the story.

- Harry Potter — a boy learns how special he is, by a famous transphobic author

- Gone With The Wind — A 1939 American epic historical romance film adapted from the 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell. The main character is older and of marriageable age, but still pretty inward looking.

- Adventureland — The main character has just finished university. But as he says into the phone at the beginning of the story, he has been so focused on academics that he has no life experience to speak of.

- We Are The Best — a group of girls about 12 or 13 years old who go on a mythological journey.

- Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery — a well-known classic about an orphan who finds a home with two elderly siblings on Prince Edward Island. However, when adapted for screen by Sullivan, the story changed from a Bildungsroman into a romance.

- Fish Tank directed by Andrea Arnold

- American Honey, also directed by Andrea Arnold

Chrononormativity and Coming-of-Age

Chrononormativity refers to the expectation that certain things happen to people at certain times in their lives.

A good example is university education. Historically, the normative time to study at university is between the ages of 18 and 25. This is changing as more of us are required to become lifelong learners, but there remains a prejudice against so-called ‘mature students‘. (The prejudice is right there in the name — aren’t students just… students?)

If we’re expecting coming-of-age arcs to happen only to young people, we may be responding subconsciously to the chrononormativity of our culture.

Chrononormativity also affects single people who ‘still’ haven’t partnered up by a certain culturally prescribed age, or older people retraining from the bottom in brand new jobs under much younger managers, or people who come out as queer/trans in late middle age… The list goes on.

Coming-of-age stories can happen at any time in a person’s life. It is chrononormativity which leads us to expect coming-of-age narratives to feature young adults.

Recently there has been a spate of queer critical work on the ways in which, in a range of works, the queer child (or the child as a trope for the potential queerness of temporality itself) functions to disrupt teleological developmental narrative (oriented toward adulthood and heteronormative reproduction), even as s/he also functions as its best guarantor.

Yet it is the adolescent, rather than the child, who holds the key place in Western literature’s most influential narrative of development, the Bildungsroman. The Bildungsroman relies for its plotlines on the choices encountered by a young person on the verge of adulthood.

According to Franco Moretti, the central dynamic of the Bildungsroman is marked by a tension between a narrative drive towards a settled telos — adulthood, marriage, and vocation — and a contrasting urge to linger in present-centred, picaresque pleasures signaled by circulating capital and an aesthetic that in the nineteenth century became identified with the emotionally charged and experimental moment of modern youth.

Jed Esty has recently noted the ways in which many canonical modernist novels feature adolescents who fail to grow up, connecting this recurring anti-developmental plot to the placement of many of these novels in colonial contact zones, “where uneven development is a conspicuous fact of both personal and political life”.

Dead Boys and Adolescent Girls: Unjoining the Bildungsroman in Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding and Toni Morrison’s Sula by Pamela Thurschwell, University of Sussex.

Telos: an ultimate object or aim.

Youth is often thought of as something transient – something we pass through as we move onto becoming adults. Going from here to there, from A to B. In the UK, adulthood is assumed to involve moving from school to work, and for increasing numbers of young people completing university, as well as moving into owned, independent housing, starting a nuclear heterosexual family and changing leisure patterns.

These markers of adulthood are tied to notions of what cultural theorist Lauren Berlant called the social-democratic “good life”. This imaginary is not neutral and is wrapped up in classed, gendered, racial and sexual assumptions that foreground global Northern ideas of adulthood as a norm, rendering other forms of growing up “other”.

What adulting tells us about the politics of linearity by Isaac Hoff, April 5 2022

COMING-OF-AGE AND QUEER IDENTITY

Some people are growing tired of coming-out stories, a subcategory of coming-of-age narrative. However, there are still plenty of storytelling gaps for non-mainstream experiences of the world.

Our amatonormative, sex-normative world considers first kisses, first relationships, first fucks, moving in together, engagements, and marriages to be milestones of maturity. These events are laid out like dominos that you must knock over to be considered a full-fledged adult.

People who do not get married because their kind of partnership is not legally granted that privilege, people who do not bear children, people whose first kiss occurs after high school or not at all, etc, are all subjected to being considered not yet. They are not yet adults, not yet mature, but they are expected to reach that domino eventually, and are ostracized if they do not.

Sexuality and romanticism are tightly connected to adulthood – resulting in kids with non-allocishet identities being told they are too young to know, and many queer identities considered a phase that one will grow out of, and hysterical reactions to teenagers who date or have sex without parental permission. (Hetero) Sexuality and romanticism are meant for adults, but you will become an adult some day!

AZE Journal

Coming-out stories tend to have a binary and linear progression: You’re in the closet and unhappy. You’re out of the closet, find your family and you’re happy. Western audiences (and especially American audiences, perhaps) are drawn to the linear progression of personal growth (and treat the grieving process in the same way, hence the popularity of the Stages of Grief from 1969).

But in reality, coming out doesn’t work like that. It’s not binary and it’s not linear. This article talks about a concept known as minority stress, which doesn’t resolve after coming out.

John Pachankis, a stress researcher at Yale, says the real damage gets done in the five or so years between realizing your sexuality and starting to tell other people. Even relatively small stressors in this period have an outsized effect—not because they’re directly traumatic, but because we start to expect them. “No one has to call you queer for you to adjust your behavior to avoid being called that,” Salway says. […] Whether we recognize it or not, our bodies bring the closet with us into adulthood.

The Epidemic of Gay Loneliness

CAN THE HEROINE’S JOURNEY BE ADAPTED AS QUEER NARRATIVE?

For The Heroine’s Journey, see this post.

- A life changing event compels a queer individual to go on a quest to find their own identity separate from the expected life progression assimilated from the dominant culture and modelled by their family.

- At first they adopt allocishet behaviours thinking that they have repressed damage from the past and that this is what they need. This belief leads them to try to assimilate into the world of the allocishets.

- This life leaves them feeling hollow, until they are unable to keep living like this.

- Something external happens to lead them to question everything they thought they knew about themself and how to live a good life.

- Deeper self acceptance follows, alongside grief for the previous portion of life in which they lived inauthentically.

- They may distance themself from the mainstream world while dealing with that particular grief.

- Spiritually arid, they turn further inward, in search of their unique self. They examine their life until now, mining for memories that seem to reflect pieces of a lost but authentic self. This means casting off societal expectations that can never be fulfilled.

- Little by little or all at once they find within themself the consolations and outright advantages to being ace. They integrate this in their own particular way and begin to express the positive qualities of queerness.

- Instead of rejecting the dominant culture outright they integrate the side of themself that holds the power of their queerness. There is no longer duality between masked and authentic self. They end the misery of beliefs and behaviours not in harmony with their newly discovered self.

- They are integrated, renewed and healed.

I can imagine this journey adapted for neurodivergence as well.

COMING OF “MAGE” STORIES

A commenter on an Overly Sarcastic Productions YouTube video suggested “Magic Puberty” to describe stories in which a teenage character realises they have magical powers. Another commenter (perhaps several, separately) suggested Coming Of MAGE as the obvious name for this trope.

GATEKEEPING ADULTHOOD

FOR DISCUSSION

Maria Nikolajeva said in her book From Mythic to Linear:

It seems that in young adult novels, there may be only two ways to deal with growing up, death or self-denial.

Do you agree with this statement as it applies to modern young adult literature (and movies and TV)?

FURTHER READING

FEMALE COMING-OF-AGE STORIES AND THE PROSUMER

Contemporary Female Bildungsromans — Leisha Jones writes about Bildungsroman and the ‘prosumer‘, a new word which has come out after analysis of the Twilight series. Jones looks at how the modern stereotype of the girl in love is a carefully manufactured product marketed heavily toward its target audience. The target audience is starting to take control of that image, using fan fiction and blogs. Fans share their impressions of the story without that mediation of the commercial product (the prosumer — a proactive consumer).

CLOSED, SEMI-CLOSED AND UNRESOLVED

In 1994 Peter Hunt wrote of ‘closed—semi-closed—unresolved’ stories forming the backbone of literature. Children’s stories tend to be “closed”. Coming-of-age stories are “semi-closed”. “Unresolved” endings are more common in stories for adults.

Books about Growing Up from the University of Miami Picturebook Database

TEEN TV (2021)

Stefania Marghitu’s Teen TV (Routledge, 2021)explores the history of television’s relationship to teens as a desired, but elusive audience, and the ways in which television has embraced youth subcultures, tracing the shifts in American and global televisual and youth cultures. Organized chronologically, Teen TV starts with Baby Boomers and moves to Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z as a way to contextualize and discuss cultural and historical contexts of teen television and television audiences. The book examines a wide range of historical and contemporary programming: from the broadcast bottleneck, multi-channel era that included youth targeted spaces like MTV, the WB, and the CW, to the rise of streaming platforms and global crossovers.

It covers the thematic concerns and narrative structure of the coming-of-age story, and the prevalent genres of teen TV, and milestones faced by teen characters. The book also includes interviews with creators and showrunners of hit network television teen series, including Degrassi’s Linda Schulyer, and the costume designer that established a heightened turn in the significance of teen fashion on the small screen in Gossip Girl, Eric Daman. New Books Network