“The Home Girls” is a short story by Australian writer Olga Masters (1919 – 1986), and the first story of Masters’ 1982 collection, also called The Home Girls. I’m interested in Olga Masters partly because her fiction wasn’t published until she was in her 50s. Then, when she was published, she won a bunch of awards. The Home Girls won a National Book Council Award in 1983.

SETTING OF “THE HOME GIRLS”

WHAT IS A HOME GIRL?

THE CONTEMPORARY MEANING

Today, ‘home girl’ means a friend (homie). (Is the term borrowed from African American Vernacular English?)

GIRLS WHO LIVE IN AN ORPHANAGE

In Olga Masters’ story ‘home girls’ means something different. Home girls in 20th century Australia referred to girls who lived in orphanages. Some of them had been sent out from England on a child migration scheme.

In Australia, some non government orphanages relied upon the labour of children in their care to supplement income. The organisations running these institutions profited from the labour of children through commercial enterprises. The children were sent to work in farms and in laundries. The institutions received payment for this child labour, not the children themselves.

‘Homes’ referred to the orphanages. Therefore, ‘home work’ for an orphanage child did not mean study and unfinished schoolwork. It referred to the unpaid labour orphans were required to do outside school time. During school time, Catholic schools would generally be the place for a handful of ‘home-girls’ who all too often sat meekly apart from the other students, who were divided into boarders and day scholars, or commercial versus science and humanities streams, but were all above the station of ‘home girl’.

Government institutions were bound by rules preventing them from renting their children out to the highest bidders, but their orphans were still often used to perform the day-to-day labour of running the institution. Children assisted with kitchen, garden and other domestic duties. Some of the domestic duties were harsh and constant. The children did not enjoy days off or breaks. They were fed too little. The word ‘slavery’ is not too strong.

Girls have always been considered little mothers in training (even more so last century), so from the age of 10 were often used in nurseries. Girls were required to care for and clean the babies and required to put younger children to bed. So-called foster families knew this about ‘home girls’, and expected fully qualified and capable domestic servants when they asked to care for a child or two in their home.

For more on the history of institutional child abuse read Inquiry Into Children In Institutional Care (2004), a report for the Australian Senate.

CHILD LABOURERS FROM BRITAIN

In the English speaking colonies attached to Britain, ‘home’ referred to Britain. (Growing up in New Zealand, my Nana always said ‘Home’ and meant ‘Ireland’, though she never once made it to the Northern Hemisphere.)

In a slightly different but overlapping meaning, ‘home children’ were sent out to the colonies from Britain via a scheme started by Annie MacPherson in 1869. A few went to New Zealand, Southern Rhodesia and the Cape, but most went to Canada. (As many as 90,000 between 1869 and the 1920s.) A further 6-7,000 were sent to Australia in the 20th century, half of them after 1945.

Most children were between the ages of 8 and 14, though a few were even younger, sent to the other side of the world under the care of older siblings.

These children were conveniently thought to be orphans. But only a small proportion of the children involved in this ill-conceived child migration scheme were actually orphans:

From the late 1860s right up to 1948, over 100,000 children of all ages were emigrated right across Canada, from the United Kingdom, to be used as indentured farm workers and domestics. Believed by Canadians to be orphans, only approximately 12 percent truly were. These children were sent to Canada by over 50 organizations including the well-known and still working charities: Barnardo’s, The Salvation Army and Quarrier’s, to name a few.

Canadian British Home Children

Children sent to Canada tended to have a different experience from those sent to Australia. Those sent to Canada arrived at receiving homes and were then distributed mainly to farming folk in need of young workers. Few were adopted. Most were given bed and board and, as they got older, some wages. Canada realised earlier than Australia that this scheme was wrong. They stopped accepting home children, but this only meant more were sent to Australia.

Those sent to Australia in the 20th century were mostly contained and trained in residential schools until they were of employment age.

Many of these children did indeed end up in paid employment as adults. But as children they were hugely vulnerable. For many, there was a childhood of abuse, exploitation and neglect to be endured before enjoying the adult freedoms of their new countries. The great majority suffered trauma, which started before they were sent away.

Wherever there exist cultures without social security, or even birth control, children are routinely born into households which cannot care for them.

Heart breakingly, many of these 20th century home children were sent out as domestic servants only as a temporary solution to financial hardship, but there was always a risk of never getting your child back. Many were sent on somewhere else, and destitute parents never saw their children again.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE HOME GIRLS”

In this short story by Olga Masters, two so-called home girls take back some power by creating their own destiny. Masters thereby subverts the idea of home girls as mindless, inconsequential domestic slaves, considered inferior stock due only to family death or poverty.

SHORTCOMING

Throughout this story, the girls remain unnamed, identified only as the fat one and the thin one. Some contemporary readers feel indignant when this happens, subscribing to the view that the disenfranchised and powerless should at least be given names, as to name them is to model respect.

But there are good narrative reasons for not naming characters. In this story, these girls are never really known by anyone, and that is the point. They are generic ‘home girls’, who have been shoved from foster home to foster home. Adults talk about them as if they can’t even hear. Even as children, these girls are objectified. Their bodies — for domestic and beauty — are their only currency of value.

The other reason to avoid naming them: These home girls are more universalised. This is the story of many such girls of the mid 20th century.

DESIRE

It’s not clear the extent to which these girls have been used as domestic labour in this particular house, but when they automatically go to strip the bedclothes from their beds it’s clear that much has been expected of them in previous homes.

The children of this story don’t have much in the way of agency. It would be easy to assume that what these girls want is a stable family, and I think that’s a given, as a basic human need. That’s not the particular desire explored by this story, though.

OPPONENT

It’s interesting that Olga Masters gave the home girls not one but two temporary mothers in this story, when she could have telescoped it by including just the one.

This is a story of duplicates, and in this respect reminds me of “The Years Of My Birth” by Louise Erdrich. The beautiful adult foster mother (who owns the numerous lipsticks) has married and is economically secure living in her own house.

The detail of the hairs in the mole of her adult spinster sister (we assume, since she does not live in her own home) is designed to evoke in readers the fleshed out imagery of a contemporary witch-like character. Witch archetypes share a conglomeration of features: a hooked nose, a hunched back, thinness, emaciated breasts. The teacher in Fun With A Stranger by Richard Yates is a similar archetype, as is the skinny older sister next door in Kate diCamillo’s Mercy Watson series. We typically feel a little sorry for these women, even as we witness violence transferred from themselves onto the children who inevitably wind up in their orbit, if not under their direct care.

PLAN

Child characters in stories for children have agency. Where there are mysteries, there is a point at which the child decides to make some kind of a plan.

But where children exist in stories aimed at adults, the more realistic way in which children operate comes to the fore. Children, by and large, do not plan. They act impulsively. This is why it’s often fruitless demanding to know why a child did such-and-such stupid thing.

When the home girls discover the lipsticks, they use them to write graffiti because it is fun, because it is a sensory pleaure, because it is a form of dress up.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In the bathroom mirror, for a moment the home girls see their beautiful foster mother looking back at them. For the reader, at first it’s not clear whether the mother has actually appeared in the mirror behind them or whether her image is imagined. This results in a mini jump scare. But no, the girls see their foster mother in themselves, because they are wearing her lipstick. Or perhaps they see more adult versions of themselves, and this helps them to move from house to house. These girls don’t have the luxury of existing as dependent children.

Stories are often better when a showdown/fight/confrontation is avoided. These can be fun to watch in action scenes on screen, but it’s always far more interesting to see what leads to a battle and what comes after than the fight itself. The battle itself is often just a mandatory scene to complete the narrative and I prefer when it’s kept as succinct as possible.

Olga Masters avoids much of a showdown because the new foster parents have already arrived to pick up the girls. The current foster mother saying goodbye, with her ‘stretched smile’ does not want to cause a scene.

Now the story bifurcates. The home girls make themselves at home in the car, while the spinster sister shows the married sister what the girls have graffitied with her lipsticks in the bathroom. As viewpoint characters, it is satisfying for the reader that the girls have made their escape. We, too, feel we’ve gotten away with something.

ANAGNORISIS

The desire of these home girls becomes clear at this end of the story: They want to impress other children. Adults are irrelevant to them. They lost trust in adults years ago. The wish to impress the four children at the new house is of course part of their need to be accepted, and to find their own version of family.

We learn that these two home girls cope with their dire situation by living partly inside their imaginations, similar to Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables.

NEW SITUATION

The repeating nature of these girls’ lives has been emphasised across the story, and we can deduce they won’t be staying long at their new house, either. The wish to impress other children rather than adults doesn’t tend to get children very far.

The detail below, which shows the girls sinking into ready-made impressions, further suggests that these girls are used to getting into back seats in general.

The fat one and the thin one got in quickly and each sat in a corner of the back seat wriggling until the leather clutched them.

“Home Girls” by Olga Masters

These particular impressions in the leather weren’t made by their own backsides, but for story purposes, may as well have been.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The ending of this story reminds me of a film by Andrea Arnold called American Honey. In that story, too, a young woman with no stable home base ends up on a trip which, at the end of the story, we understand will never end. This is basically the Snowpiercer trope.

TV Tropes details a trope called ‘The Eternal Engine‘, seen most visually in a 1980s computer game, with pistons and traps which go on forever and ever. In these games, as in this story, the characters are never individuated.

RESONANCE

In literature we are still reckoning with our recent past of horrendous abuses done to children in state care. Alex Wheatle’s novel Home Girl uses the terminology of an earlier era to describe a contemporary situation.♦

FAT GIRL, THIN GIRL

Are stories in which two girls individuated mainly by their BMI problematic?

Here are some other examples.

NOVEL

Mary Gaitskill wrote a novel called Two Girls: One Fat, One Thin. Gaitskill does not shy away from topics which scare other writers. Gaitskill explores themes around body image, sexuality, and gendered power struggles. Gaitskill’s work subscribes to the view that in order to critique something you’re going to have to name it.

FILM

The French film Fat Girl (2001), written and directed by Catherine Breillat, is also about the experience of a girl considered specifically fat in comparison to her thin sister, but the French title is À ma sœur! (To My Sister). It was decided by English translators/marketers to centre the teenage main character’s weight as the most important part of her identity, and the main reason for why things happen to her.

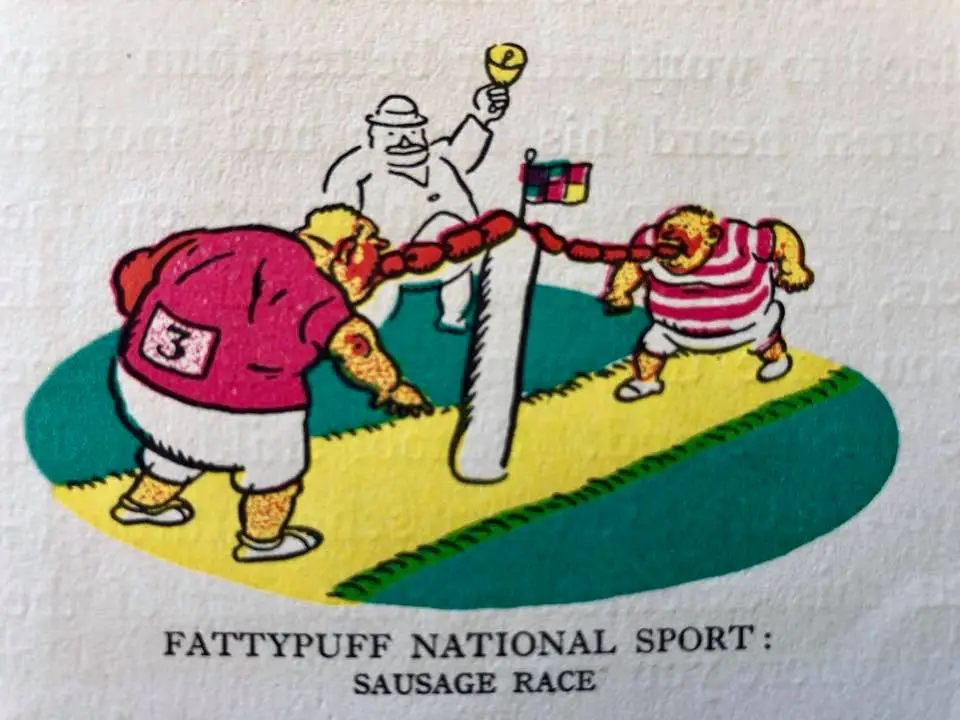

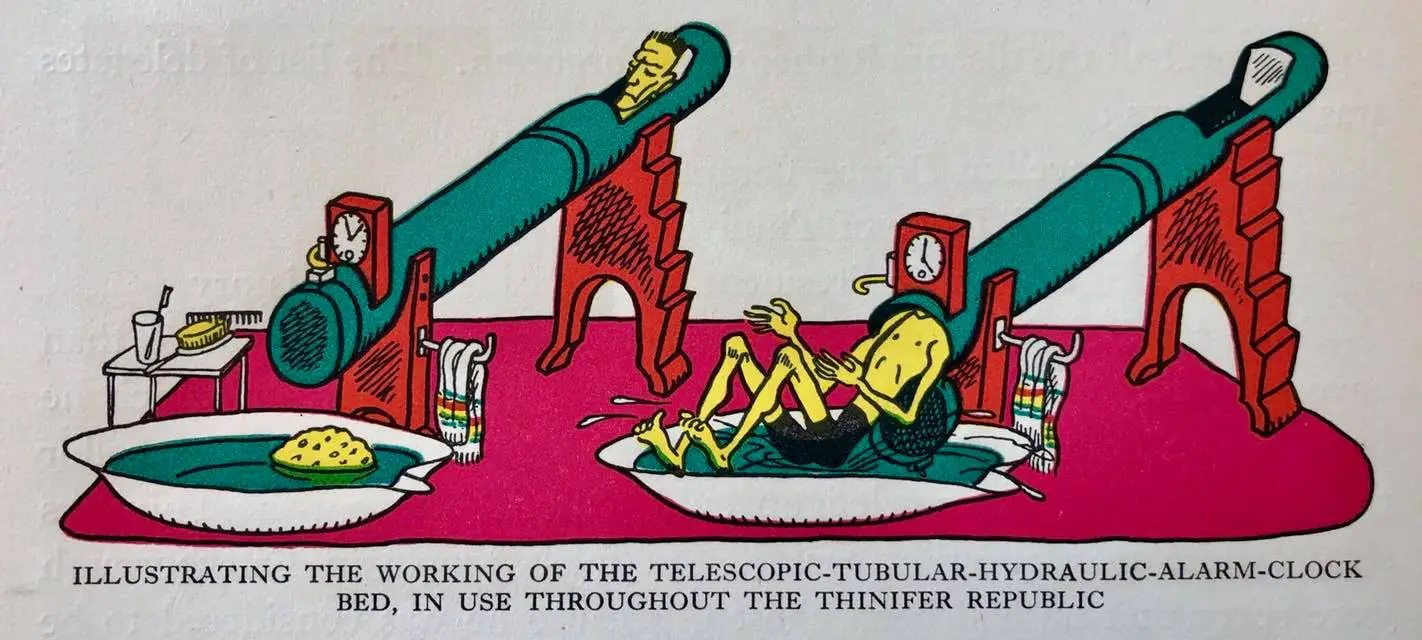

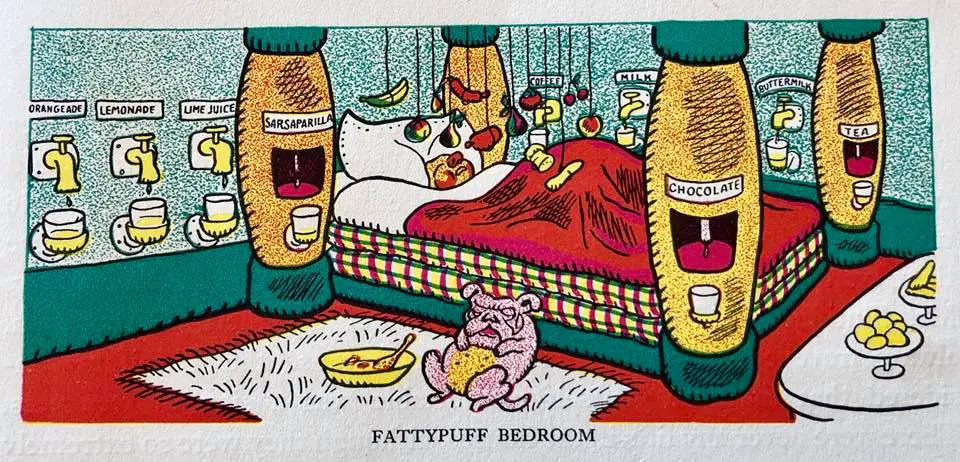

CHILDREN’S PICTURE BOOK

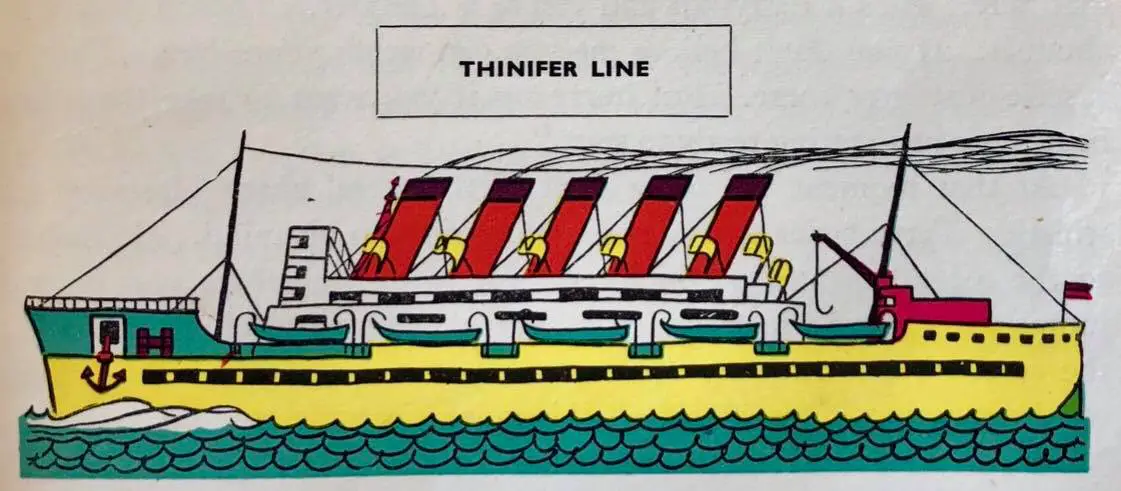

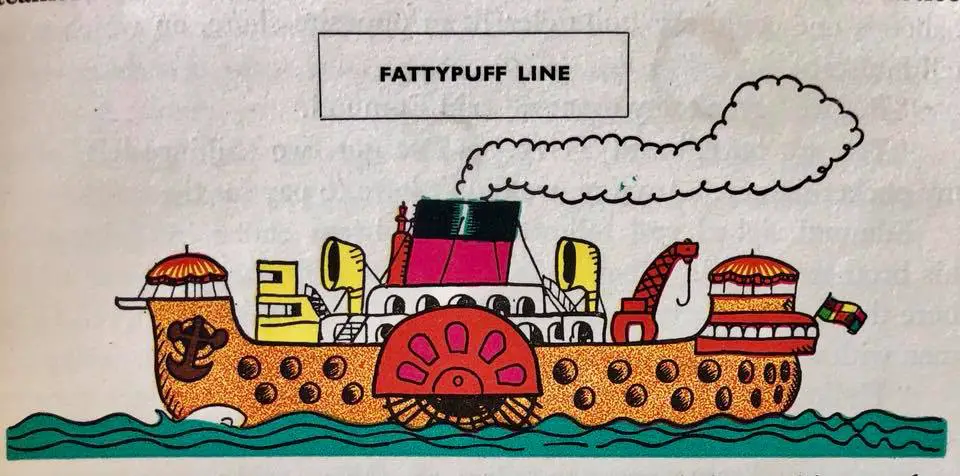

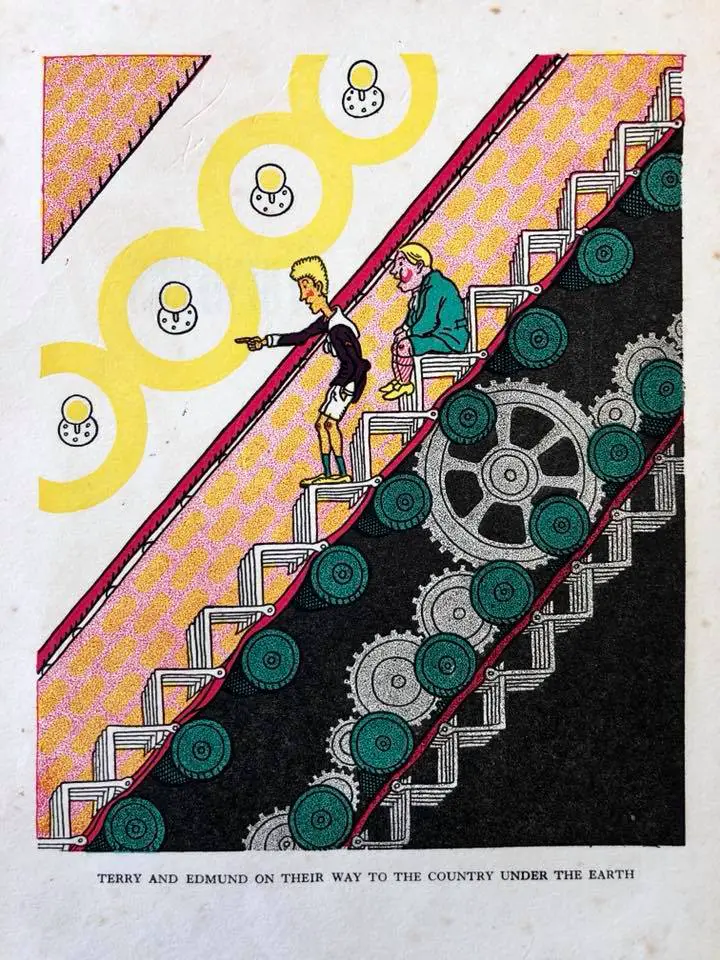

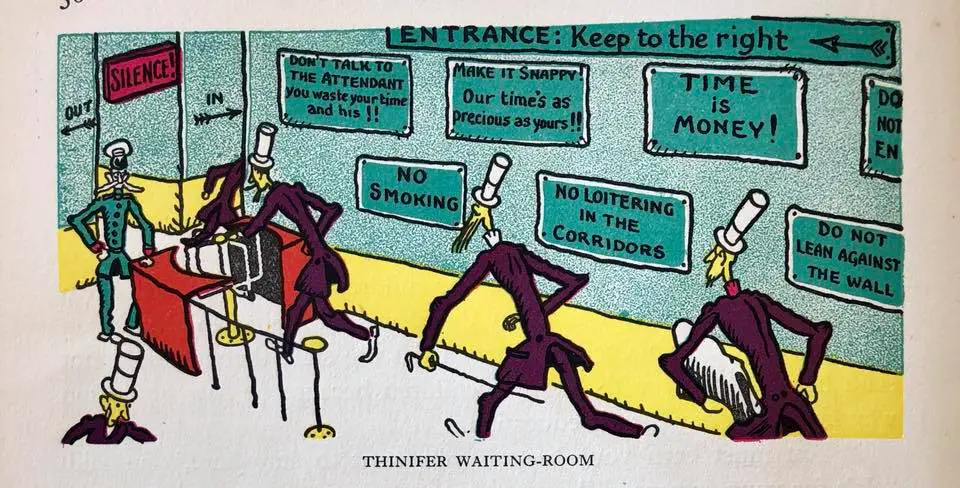

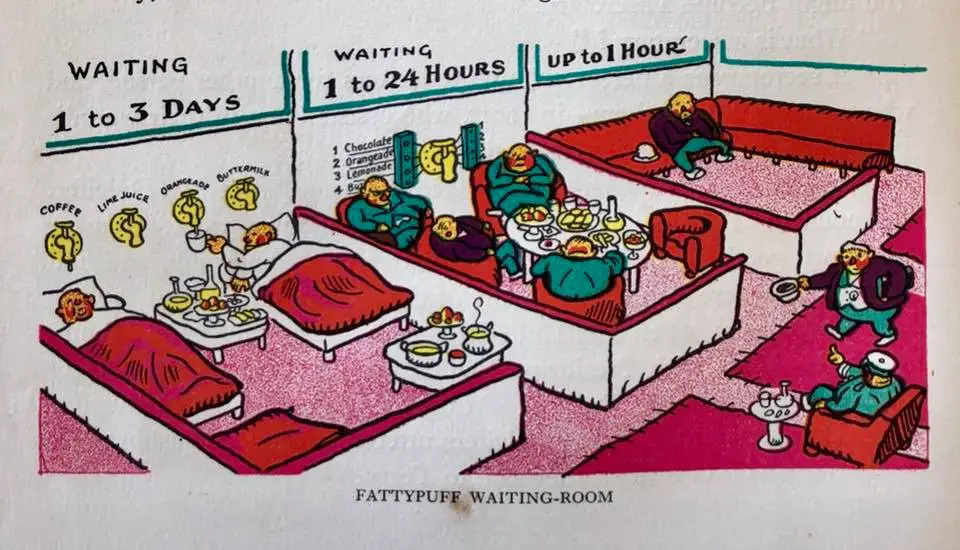

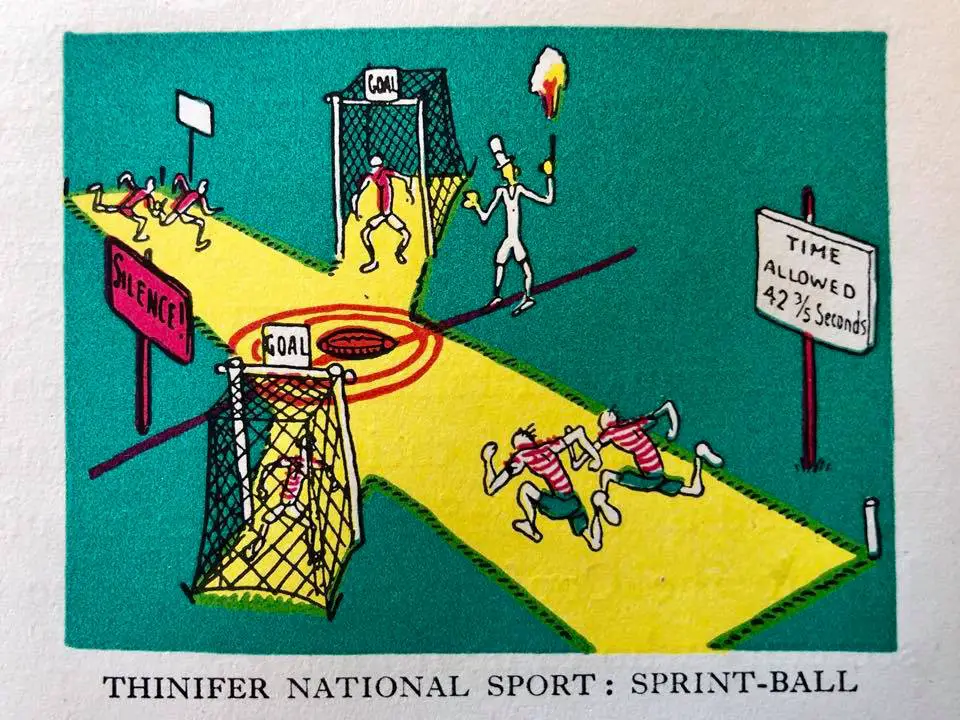

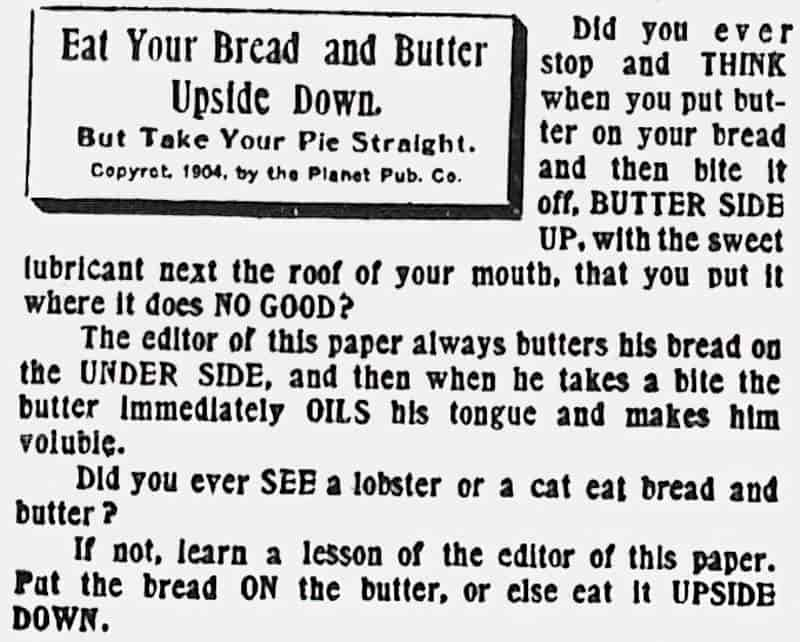

The illustrations below are by Jean Bruller from the 1941 English translation of Patapoufs et Filifers (1930) by André Maurois. The English title is Fattypuffs and Thinifers (1941). This children’s book is a little like The Butter Battle Book by Dr Seuss (1984), except instead of two warring tribes who butter bread on different sides (and fight about it), these two groups are separated by fatness vs thinness. The book uses language we wouldn’t see today.

The story starts with two brothers, one thin, one fat. They discover an underground world where a race of thin people and a race of fat people are constantly warring. The brothers become involved in a diplomatic capacity as the two declare war on each other and manage finally to help broker a peace between the two nations.

André Maurois was the French Official Observer attached to the British General Headquarters in WWII and had some personal experience of diplomacy between European nations in the run-up to and during the war.

The body types of the inhabitants reflect the setting: in one everything is sensuous, indulgent and plump. In the other where everything is harsh and emaciated.

SEE ALSO

The Ideology of Fatness In Children’s Stories

Why so many orphans in children’s literature?

Header painting: William Frederick Yeames – For the Poor