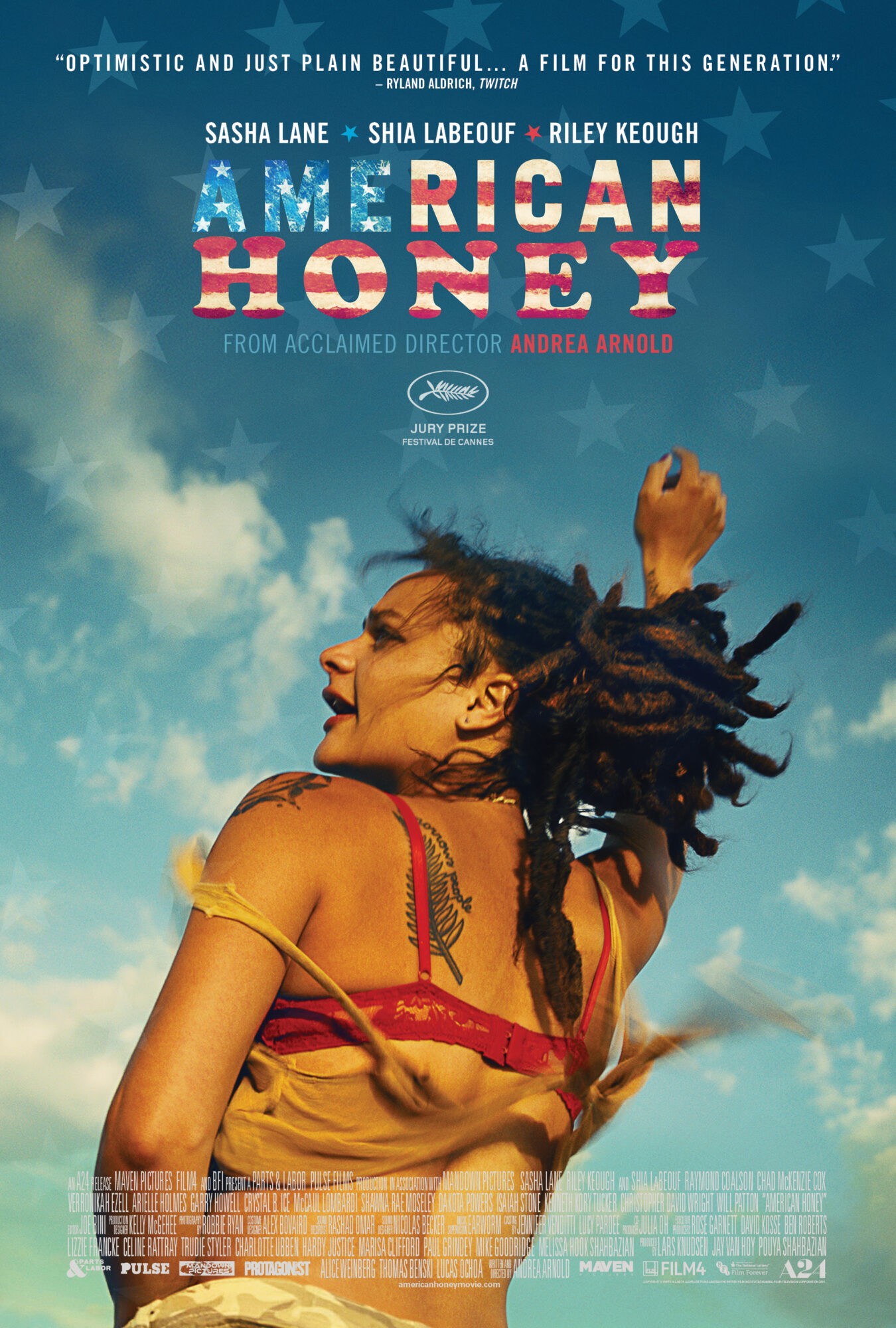

American Honey, directed by Andrea Arnold, is the granddaughter of Thelma and Louise — a road journey with classic mythic structure which follows the coming-of-age (or not) of an 18-year-old named Star. Star comes from a tough background — the classic orphaned underdog, with a mother who has overdosed, and an auntie(?) who requires Star to look after her young kids rather than looking after Star, who definitely needs protection, from the abusive guy she’s got hanging around.

Star has an allegorical name — an ironic name, because this kid will never be a starlet. Refreshingly, she doesn’t even want that. Star explains to Jake that her mother chose it because we’re all made of ‘Death Stars’. Now it’s not ironic. This is an example of Heidegger’s Being-toward-death — Star has already had this character arc. She’s lost her mother to meth. She’s faced death before. By this point in her 18-year-old life she’s learning to live with the fact that we’re all headed for the grave. This explains her hedonism. When Star explains her name to Jake, this is more of a revelation to the audience than to Star herself. Star has not fully come to terms with death — that takes some decades. She mulls it over on several occasions — when she realises the trucker she hitched with has been carrying a load of cattle, and when she accidentally steps in blood (or what looks like blood) in a ditch.

It’s inevitable that a disenfranchised kid like Star will fall into bad company, because most any company is better than what she’s starting out with. Bad company rolls into town as a band of magazine hawking troubadours in the guise of magazine salespeople, with a subculture reminiscent of Lord of the Flies. They’re headed to Kansas — synonymous to most outside Kansas with The Wizard of Oz — another mythical journey starring a girl. Arnold encourages the connection with a cut to a pair of sparkly red shoes which belong to Star’s little cousin. But this is no dreamland. This crew are outlaws with their own set of rules. They punish each other physically for coming last in their sales ranking system. This is headed by a matriarch rather than a patriarch, and reminds me of Alex Garland’s The Beach. The matriarch as villain is an interesting device in a feminist film, and at this cultural moment almost a necessary one, to avoid the hackneyed old ideas of women as one hundred percent victims of the patriarchy, or the dreaded Female Maturity Formula, in which girls have already been through their character arcs, existing only as models for boys to have theirs. We need more female villains. Krystal is wonderfully complex. We get just enough to wonder about her backstory.

Other reviewers have doubted the entire premise of this road trip — who buys magazines anymore? Andrea Arnold lampshades this by having Star ask it up front. What’s never clear is if there are any magazines. If there were, they wouldn’t make money. My interpretation is that there are no magazines. People are paying for a scam. The magazines exist only to justify the begging. Why else do they need to travel so far to get away from each town?

Freshly free of childcare responsibilities, Star’s road trip kicks off. Road trips are hard to write well. They tend to feel splintered — one damn encounter after another. The road trip is by nature a linear plot shape — a masculine plot shape. But when road trips star girls and women, they tend to look a little different. Star’s trip is circular, as they move through areas completely foreign (wealthy and built-up) back to a poor area which reminds Star of her own home. Female journeys are more likely than male journeys to be circular in this way.

We now get to see the childlike side of Star, who isn’t ready for the world of work. She plays the fool, gets high, and doesn’t know a violent man when she sees one. If Jake promises her ‘a present’, she’s putty in his hands. She’s come from nothing, so a present equals love. This movie is basically a love story — or can we call it that? It’s not a love tragedy, either. Like Arnold’s Fish Tank, this is the arc of an emotionally neglected teenage girl falling in with a bad older man, then finally making her escape, or not.

Arnold makes sure we empathise with Star by giving her numerous Save The Cat moments — twice she rescues an insect. Eventually she uses her sex work cash to buy groceries for neglected kids. Star has a strong moral code, in opposition to Jake’s. She has no time for lying and bullshit. Her reaction alone tells us a lot about her backstory — she’s had nothing but lies and bullshit her entire life. She’s also empathetic because she doesn’t want for much, and we see that as an endearing thing. She meets a trucker and tells him she wants lots of kids and her very own trailer. It never crosses Star’s mind that she could maybe have an actual house. The truck driver himself comes across as extremely empathetic — unlike the truck driver in Thelma and Louise, he’s not turned into the villain — he’s big into boats but despite driving miles for his job, he admits he’s never been to the ocean. He’s not young. We know he maybe never will. This could be Star in three decades’ time — it’s quite possible Star will live her life dreaming. And is dreaming enough? That’s where the symbolism of the magazines come in. If anyone wonders why people would still buy them, the trucker gives us the answer — the magazines are dreams — dreams that even poor people can hold in their hands. The trucker buys two subscriptions, and for him, that will have to satisfy his love for actual boats.

The film employs only a couple of professional actors — the rest are amateurs recruited from carnivals and suchlike. This feels like cinema verite. Each of them looks interesting and distinct. It feels like the actors were left to ad lib. You really feel like you’re in the bus with these young people, for better or for worse. If you’ve ever been on a bus trip, to summer camp, stayed in a hostel, flatted, or partied, you’ll get this.

There’s commentary about rich and poor in America as the bus travels from mega wealthy to poverty stricken areas, where the problems look different. When Star gets to the house of neglected children we’re given closeups of photos pasted without frames to the wall, a near empty fridge, Mountain Dew. This is how we’re shown, tis could be Star’s own house. She’s missing her little cousins and now she’s back in Texas, where she grew up with her meth-addicted mother, she’s come full circle. This is the beginning of her epiphany, though we never get to see what that epiphany is. Maybe she realises this is her entire lot in life, which is why she buys food for these strangers with her sex work money. Or maybe she realises she can use situations like these as a negative example, and start planning to get out of it. The overall message is egalitarian — echoed in the film credits, which list only names, with no distinction between actors and film crew. Krystal explains that poor people will buy magazines because they feel sorry for you, but rich people will buy them because they feel guilty for being rich. Krystal’s take on life may or may not be accurate, but this is how Arnold encourages to view the rich and poor as basically the same, only with different angles on the same societal problem of late stage capitalism.

There’s commentary about homophobia — it’s subtle, but one of the gay characters doubts he can go door to door in redneck country. Subtext reading: he’s not safe here. There’s little commentary on race — this is not Andrea Arnold’s story to write. Our main girl is a woman of colour, but this is a story about white America. It’s clear these white kids identify with Black culture — they have a love for rap and call each other the n-word. It’s left up to us to decide why these kids align themselves with a culture that’s not entirely their own.

The ending is left open for the viewer to extrapolate. Jake gives Star the turtle and she sets the turtle free. Then she joins the turtle in the water. One interpretation: Star is now free like the turtle, having experienced a revelation. Meanwhile, the others dance over a fire to Raury’s tribalistic anthem ‘God’s Whisper’. If that’s not religious imagery of rebirth, I don’t know what is. Then again, Star has given away Jake’s (stolen ring) present before — is this the part where Star finally sees this violent, coercively controlling man for what he is? Maybe. But if she doesn’t see it now, she never will. Take a close look at the lyrics to God’s Whisper, though — you may need to look them up because the song feels morphed and warped in the film — and it’s clear Star has realised who Jake really is:

I won’t compromise

I won’t live a life

On my knees

You think I am nothing

I am nothing

You’ve got something coming

Something coming because I hear God’s whisper

Calling my name

It’s in the wind

I am the savior

(Sing it again!)

Savior

Savior

(I can’t hear you! What?)

Savior (What?)

Savior

The outro music is “I Hate Hate” by Razzy Bailey — an ironically breezy tune with children backing up in the chorus.

That’s why I’m singing now

I hate hate, everybody sing it with me

I hate hate, let’s all get together now

I hate hate, the good Lord above

Don’t you know I love love

Oh, you got to have love

“I Hate Hate” can be interpreted in two ways. The singer either despises ‘hatred’, or they really, really hate something (with the double ‘hate’ serving to emphasise). I interpret this choice of song as Star’s acknowledging to herself that she hates this man, but this experience isn’t going to stop her from living life to the full. It’s okay to acknowledge the bad stuff, and that’s how we move on. Mind you, the irony could have a darker side. She could acknowledge this guy’s terrible and yet choose to stay with him.

For us, Star’s journey ends here. Does she use this newfound hatred to escape? For all we know, this young woman could keep traveling these American highways forever, trapped in a hot bus with a bad man and a stifling, drug-addled rag-tag crew who don’t seem to see abuse when it’s right in front of them. This is the water they swim in, and this is how abuse works. Streetwise matriarch Krystal does see it, but she’s toxic and ignores it. She may even revel in watching it play out, accepting the abuser back when she promised his victim he was gone.

Why do girls fall for these guys? Many outsiders have wondered that about women who stay with bad men. Star’s journey in American Honey affords us a view of destructive attraction from the inside, because Shia Labeouf makes an excellent job of him. He’s been well-written, too. We should now be left with a little insight for how these relationships happen, and empathy for the girls involved.

Although American Honey is comparable to Thelma and Louise, I make the comparison mainly because there are so few road trips starring women. Arnold avoids the problematic, overdone trope which concludes Thelma and Louise — that in order to achieve perfect freedom, a female character must pay the ultimate sacrifice: her life. (In stories about men, it’s more often the male best friend who pays with his life.) I am left hoping for the very best for Star. I think she might be okay now that she’s a little more worldly. More importantly, the real-life audience might be a bit more okay, too. Watch this with your young adult daughters and discuss with your sons.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Red Road was Andrea Arnold’s debut.

I’m also a big fan of Fish Tank, which won a BAFTA.