Time travel! Romance! Japan! If you love the films out of Studio Ghibli you’ll love The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, too.

ARC PHRASE

An arc word/phrase is also known as a ‘leitwort’, which literally means ‘lead word’. In order to be an arc phrase and not just a catch phrase the phrase must help define the tone of the entire work, or at least the plot arc.

‘Time Waits For No One’ is a fairly cliched English phrase, but perhaps a Japanese audience finds it a little more exotic, like we find Chinese characters exotic when we tattoo ourselves with them. This idiomatic expression is written across the black board, presumably after an English language lesson, and explains the basic message of this tale: Even if you had the ability to go back in time and change things, you wouldn’t be able to do anything about the basic nature of fate.

The magic in a very early Twilight Zone episode called One For The Angels (in fact this is the second episode ever) is such that even if you yourself manage to avoid death, the fate must be transferred to someone else.

Proud of having outsmarted Mr. Death and now virtually assured of immortality, Lou is informed by Mr. Death that “other arrangements” must now be made, that someone else will have to take his place. Mr. Death chooses a little girl, one of Lou’s good friends who lives in the same building. When she is hit by a truck Lou immediately offers to go with Mr. Death but is told it is too late.

Wikipedia

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a Japanese anime from 2006 directed by Mamoru Hosada, who is also known for my daughter’s favourite Wolf Children and the long but engrossing Summer Wars. This film based on the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui, which was originally published way back in 1967. It has been adapted many times.

For example, there was another (non-anime) film adaptation of this novel made several years later in 2010, but reception wasn’t as good. (Yasutaka Tsutsui also wrote the book Paprika, another well-known anime adaptation.) After the novel The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was adapted into film, it was then adapted back into book form, this time as a graphic novel.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time has elements of a portal fantasy.

What Is Portal Fantasy?

If the story takes place in a world other than our own, it is fantasy.

If the story starts in the real world but the characters enter a new one in the story, that is called a Portal Fantasy.

Classic fantasy takes a single main character from mundane world to fantasy world and back to the mundane. So, classic fantasy is also portal fantasy.

A passageway is normally used in a story only when two subworlds are extremely different. We see this most often in the fantasy genre when the character must pass from the mundane world to the fantastic.

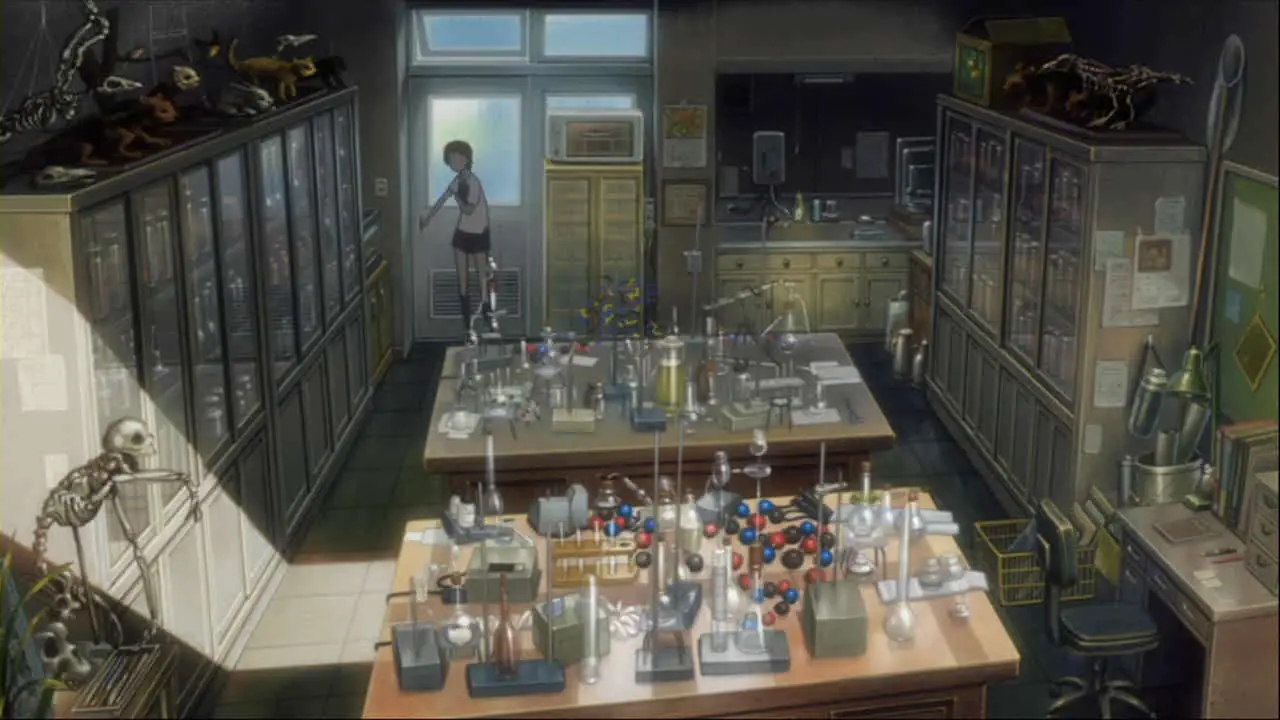

The room into the science lab beside the classroom is treated as a kind of portal, with the camera lingering on the door, with a shadow forming a cross over the door. Inside there is a kind of witch’s lair. The mother has already mentioned a ‘witch’ in jest when saying goodbye to Makoto in the morning. She finds something magical on the floor. The colour scheme switches to blues as we accompany her through time, with images of mustangs running across plains and something like the inside of a computer.

This is also a coming-of-age story.

What Is A Coming-of-age Story?

A coming-of-age is film genre that focuses on psychological and moral growth of a protagonist who is growing from youth to adulthood. Personal growth is the most important characteristic in this genre; it relies on emotional responses and dialogue, rather than action.

After finding the time-leaping device Makoto visits her auntie witch who works at an art gallery. Auntie exists to explain the magic/science of time travel and it often happens to girls your age. This marks the motif of the time-leaping device as a metaphor for growing up and its confusion, as well as the almost universal desire to have do-overs after you’ve reflected on a mortifying scene in your teenage life and performed less well than you would’ve liked.

I would also argue that this story is an example of magical realism.

What Is Magical Realism?

Magical realist stories are basically set in the ordinary, everyday world we all share but there is a little bit of magic, unexplained to the audience. We just know that it’s there and accept it. In the case of this story, Makoto’s mother wishes her goodbye in the morning and makes a reference to her going to see her ‘Witch Auntie’. We don’t know exactly why this woman is a witch, but we accept that witches exist in this world.

If the mother had not mentioned the witch auntie I would be more confident in calling this magical realism, because ideally there should be some doubt in the reader’s mind about whether the fantastic elements are real or not. If they mother hadn’t been ‘in on it’ the visits to the witch auntie might well have taken place entirely in Makoto’s mind.

FEMALE RELATIONSHIPS

In the West it can be difficult to find good stories about girls who are friends, without being ‘frenemies’ or without fighting over a boy, or over who looks the prettiest. The abundance of mean girl tropes is frustrating because it’s simply not how female relationships work, and it paints girls out to be nothing but bitchy. To find some excellent stories about female relationships we can instead go to Japan, where we’ll find stories such as this one, with its more nuanced female character web.

IS THIS A FEMINIST STORY?

The film poster itself is a shot of a high school girl who seems to be dressed from the male gaze. By Western standards, the school skirt is far too short. I’ve yet to work out though if Japanese culture sexualises legs to the extent that Western culture does. Short skirts in Japanese schools — at least those that don’t rule otherwise — are very short, and I believe it comes from the fact that legs look longer if skirts are shorter. (An optical illusion as much as an expression of sexuality.) What I am quite sure of, though, is that this female main characters in Western animations are not designed with such short skirts unless that character is the designated hot mean girl.

There are a number of diehard tropes that come out of Japan. One of them is the sharing of the umbrella as a way of striking up a relationship with a stranger you meet on the street. Which is fine. It’s the classic ‘meet cute’ scene, and is common in the West as well.

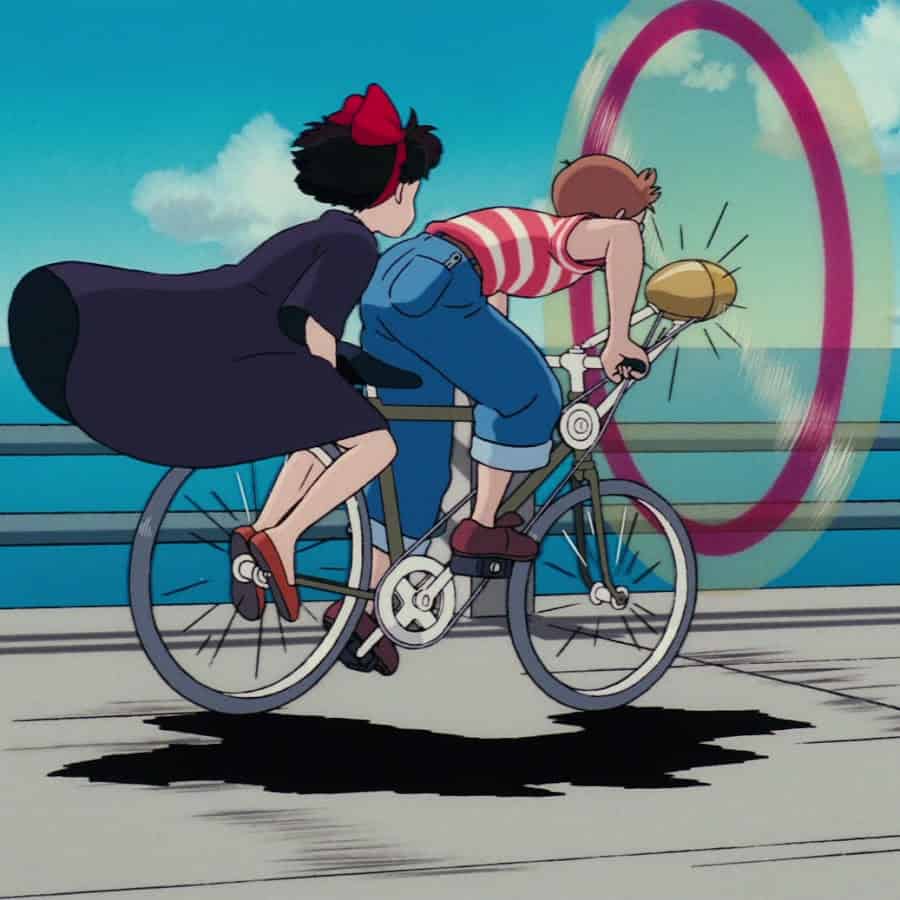

Another is the ‘riding bitch’ trope, in which we see a boy give a girl a ride home on his bicycle, him leading the way.

This trope is popular in Studio Ghibli animations also.

Is there anything wrong with the riding bitch scene? When it happens over and over again it tells boys they must take the lead and girls that they must submit. The real problem is that we never see the gender reversed. That’s when you know it’s a problem.

There is a danger in ‘tomboy’ stories that they border on femme phobic. The empathetic female protagonist has short hair, a unisex name, likes to play baseball and hangs out with guys. She could easily become your classic ‘guy’s gal’, the kind who would say things like, “You know, I really just prefer guys over gals because gals are waaay too much drama.” (Internalised misogyny.) This film avoids that because Makoto doesn’t only have guy friends, she is also close to a girl, and she has a slightly dramatic but loving relationship with her sister, too.

Another thing I like about this story is that the girls are allowed to eat. Makoto works up a ravenous appetite by extending her days time-leaping. She raids the fridge in the way most often attributed to teenage boys.

THIS STORY AS AN INSIGHT INTO JAPANESE CULTURE

When Makoto falls asleep in class her teacher drops a book on her head. While unacceptable in the West, I have seen this sort of interaction happen in Japanese classrooms in this general era — male teachers in particular can sometimes slap students about the head and come down heavy with the ruler right next to someone’s hand. This sort of intimidation is no longer acceptable in many countries.

The ‘purin’ that Makoto’s little sister eats is a loanword from English ‘pudding’ but refers to a specific product. The purin is as much a part of Japanese childhood food culture as the Twinkie seems to be in America. It’s basically set custard that you eat cold out of the fridge in summer.

In the fridge you can also see cans of Asahi beer, almost certainly for the father’s consumption. They eat teppanyaki one night, which the more feminine younger sister has helped the mother to prepare. Japanese housewives spend a lot of time in the kitchen, as traditional Japanese meals require a lot of preparation time. (Similar to Indian food in that regard.)

Japanese high schools don’t employ cleaners. It’s up to the students to clean their own classrooms daily, and at the end of each term there is an entire afternoon spent on ‘Big Cleaning’, in which students scrub the corridors and toilet floors. It’s therefore quite normal that Makoto would be doing the errand of delivering the stack of books to the science lab, even though in my Western high school this room was full of dangerous chemicals and equipment, and therefore off-limits to all students unless a teacher was present.

Story Structure of Up On Poppy Hill

Anagnorisis, need, desire

Makoto Konno is the classic loveable heroine: clumsy and nondescript (like Bella Swan) who describes herself as average in ability. This is a story of an ordinary girl in an extraordinary situation. I mention above that she is a Japanese ‘tomboy’. Her body language is masculine. In Japan it’s frowned upon for girls to cross their legs while sitting on the couch. When laughing you cover your mouth. But Makoto’s body language is wide and expressive and when she laughs she throws her head back and her mouth becomes comically huge. If you listen to the original Japanese she speaks in a much more masculine manner than the English dub would lead us to believe, even referring to herself as ‘ore’, which is slang for the first person pronoun and generally used only by boys.

Even the name Makoto is more commonly given to boys in Japan (though it’s reasonably popular among girls, too).

Symbolic names work best in comedy and children’s literature.

真琴 is the kanji used for Makoto’s name in this story. When written like this it’s generally a given name for boys. The ‘koto’ refers to the traditional Japanese stringed instrument. ‘Ma’ means ‘truth’.

(The first name of the original 1967 novel was Kazuko is now an out-of-date sounding name, because it was very popular after WW2. In that era girls were given ‘peace’ names, and Kazuko is often written as ‘Peace Child’. It’s therefore reminiscent of grandmothers (and great grandmothers).

Makoto, phonetically, means ‘truth’, which makes this an allegorical name, or an ‘aptronym’ — Makoto must learn to be truthful rather than mucking people around, using time travel to play with their emotions.

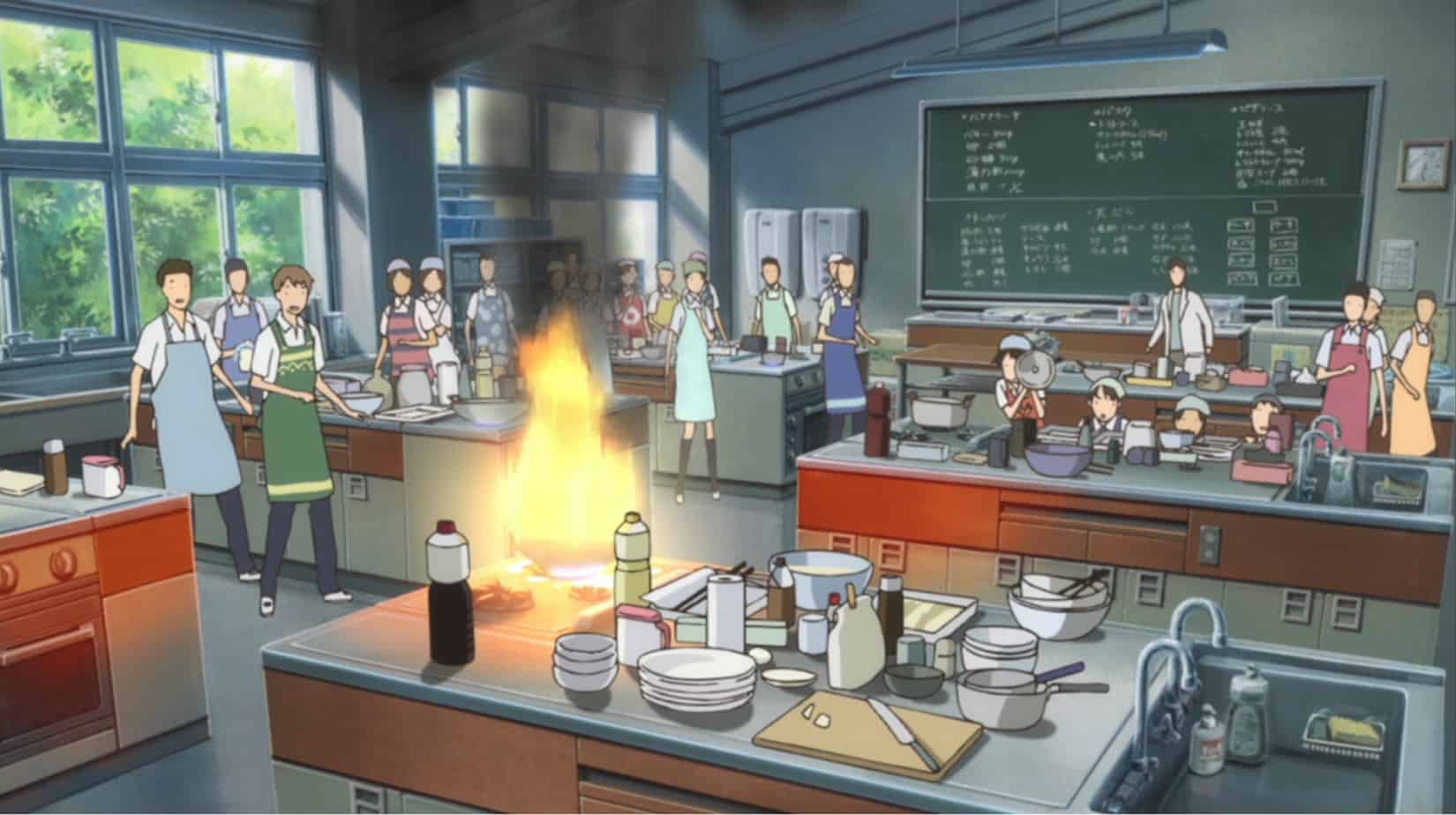

Makoto is always leaving disaster in her wake, like setting fire to a pan in cooking class. She tells us via the storyteller narration that she has no real skill in anything and doesn’t even know if she’s going into arts or sciences in senior high school. This is a very important decision in her Japanese life in her third year of middle school because she’s about to enter the ‘study hard’ years. She jokes with her friends that she’ll be a media tycoon or maybe an oil baron. ‘You need to take life more seriously,’ she is told.

This is a specifically Japanese psychological need for a main character –- in Hollywood you’re more likely to find a main character who needs to lighten up a bit, especially when it comes to teenage girls, who often have their glasses removed as part of their character arc.

Ghost (backstory)

The ghost is something that happened to a character in the past that explains their motivations and reactions. The ghost will be revealed at some point in the story, often quite late.

Since Makoto is depicted as the ‘every girl’ (with a tomboyish nature to make her more endearing) there is nothing really unique about her. A Japanese audience (especially girls, perhaps) will be able to imagine themselves in her position, in this generic Japanese suburb. Therefore, Makoto doesn’t have her own ghost.

The ghost instead belongs to the mysterious Chiaki, who has a secret — where did he come from? Chiaki even gets a ghostlike sequence when he disappears in the ‘statue’ scene, where he and Makoto walk through the frozen crowd. First his body disappears, then Makoto can hear his voice, then he fades away to nothing as if slipping into death.

Setting

Place

This story is set in a middle-class Japanese suburb and high school — Shitamachi in Tokyo, which is closely connected to the area of Yamanote. (Shitamachi means Under City.)

This is more like the residences you’ll find in Shitamachi these days. (Google street view.)

Any standalone house in Tokyo is very expensive. This is an affluent family and although Makoto needs to watch her purin to make sure her little sister doesn’t nab it first, things like money and starvation are never an issue. This is a Wind in the Willows type of utopia, where the necessities of life just are. All that’s left is to worry about the social aspect. Even the news announcer is talking about a day which has been designated as a celebration of nice. Makoto runs to school saying ‘Good morning!’ to everyone.

Japanese high school students spend long hours in school and more than in Hollywood high school dramas, this high school feels homelike, with the characters trusted to relax inside the classroom, gazing through windows as if from their own living rooms.

The house where the main character lives is ‘cottage-like’ insofar as a Japanese suburban house can be described as such – there are vines growing attractively across the front.

This suburb is almost a kind of utopia — people are basically kind to each other and there is no real feeling of physical danger.

Among this suburban utopia though, commuter trains running through suburbia present a vague threatening presence; there is just an inadequate safety bar between pedestrians and instant death. Trains are the opponent in nature, the forest equivalent would be a hungry wolf, leaping from behind bushes.

In the vicinity of the train line in the shopping district is a town clock featuring creepy elves. Childhood images equal horror symbols in Japan as in the West, with our clowns, night-time playgrounds and ice-cream van music.

The river running through the suburb is where Makoto goes to practise her time-leaping, and is also a universal metaphor for the inevitable passage of time — the message in this story is that, try as you might, you’ll never really alter the inevitability of getting older, and you can never truly go back. This is demonstrated when Makoto tries to replay things, but finds they are never exactly the same second time around.

The crossroads where Makoto meets with her two friends (time and again) have a sign which says ‘koko kara’, meaning ‘from here’. I haven’t seen this road sign in Japan so I don’t know if it’s a real thing, or a motif designed specifically for this movie. The sign seems to be asking the question: Which road will you choose from here?

Time

The story is set in the modern era – the flip phones give us a guide as to exactly when. (That said, flip phones seem to be making a bit of a comeback.) Housewives put dinner on the table. Fathers go to work. Children are given full autonomy to conduct their own school lives during the day. This is no doubt partly due to the fact this is based on a 1967 novel, in which mothers almost always stayed at home and suburbs were almost always safe.

It is July – the height of summer, and they are in the middle of a heat wave. We hear lots of cicadas, which for mainland Japanese mean heat. Our story starts on July 13. Time is important to the plot so we’re told the exact dates and times of events. Clocks are everywhere, in every form — on phones, announced on the TV, digital and analogue clocks. The main characters are planning what they’ll do during their upcoming summer vacation – they discuss attending the fireworks festival together wearing yukata (summer kimono) or going to the beach.

Shortcoming & Need (Problem)

Makoto’s childhood is about to be left behind because she is preparing to enter senior high school, which in Japan is a really tough undertaking. Once Japanese students get into good universities they are permitted to slack off a bit, but those three years of senior high school definitely mark the end of childhood. (In the West I argue that the age of 12 marks the end of true childhood, at least in children’s stories.) This is symbolised by Makoto being required to choose either the arts or sciences track but having no idea. This is a big problem for her.

That said, high school — at least, the high school in this story — is a kind of utopia. High schools as depicted by Hollywood are so often cold, hard places, and always have the symbolic locker scene, and the running of the gauntlet down the hallway, planning routes to avoid bullies. Bleachers are scary places where bad things can happen. Locker rooms even more so. But this Japanese high school, which looks exactly like a fantasy-enhanced version of the Japanese high school I attended on exchange in the mid nineties, is utopian in nature.

Utopias in Young Adult Literature

It’s significant that this film is based on a young adult novel from the 1960s because we have since entered an age (and I include Japan in this) of the ‘snail under the leaf setting’, in which everything seems hunky dory, but scratch the surface and you’ll see the horror and the rot.

In Sweden, a critic [Sonja Svensson] has coined the notion of idyllophobia, a fear of presenting the world of childhood as idyllic. Children’s and juvenile literature becomes more and more violent, not necessarily in actual depictions of violence, but in the general attitude toward the essence of childhood. The narrative strategies which writers use, most often the autodiegetic unreliable young narrator, amplify the tone of the novels as uncertain, insecure and chaotic. In many novels, notably Cormier’s I Am The Cheese, we see a total disintegration of character, narrative and structure. YA novel as a narrative which goes beyond the point of no return to idyll also transgresses all conventions which are normally ascribed to children’s fiction.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

So Makoto needs to make some big decisions in her life about her future but she is no good academically and has no idea what she wants to do. Most kids her age would at least know whether they are of a science or literature bent, but Makoto needs more time to grow up before facing these decisions. One way around that, of course, is to play around with time. Her days are about to become much longer and jam-packed, because she’ll be reliving the same day over and over until she gets it right, in a Japanese version of Groundhog Day.

Many high school aged main characters are outsiders. I don’t get the feeling that Makoto is an outsider at the beginning of the story. Rather, her magical experiences turn her into a kind of outsider as the events progress.

Inciting Incident

At the beginning of a coming-of-age story, childhood has already been left behind, and the hero has concluded that the world is not a safe or blissful place. An event that occurred prior to the beginning of the story, or the hero’s overall situation, has made the hero feel lost or stuck in a world over which she has little or no control.

After the hero’s introduction in the setup of the story, she is presented with an Opportunity that will either make life even worse, or will hold the promise of some escape from his pain. In response, these heroes’ outer motivations are declared, and their pursuit of those goals begins.

The Opportunity Makoto gets is the magical ability to leap through time and have do-overs. This is made possible by the discovery of the time-leaping device, and with practice she learns how to make use of it.

In the original novel, the protagonist is cleaning the science lab and is overcome with the overwhelming scent of lavender. She wakes up three days later, therefore spending significant time in the portal. In the film, too, the screenwriters make sure to linger on the science lab. First we have the door. (The portal is literally a door in this story.) The shadow moves to form a cross on the door knob, as if daring Makoto to enter. The lab is chock full of equipment which gleams in the shaft of light coming through a window — this is a beautiful depiction of a science lab and invites the eye to linger. It’s more like a witch’s lair than a school equipment room.

Desire

At the beginning of the story Makoto only desires to be left alone in her childlike state, playing baseball with her friends after school, planning fun things to do over the summer holidays, singing karaoke.

There is no oft-mentioned ‘Call to Adventure’. I don’t think many modern stories operate on that basis. It’s only ever young men pumped up on testosterone who have had the desire to go out and save the world of their own volitio n, and those stories now seem old-fashioned.

Ally/Allies

Chiaki has reddish hair to mark him out as distinct from Kousuke, in a classic red-devil, blue-devil trope. The coloured hair also makes Chiaki seem more alluring and mysterious. Kousuke, in his sexy glasses, is the brains while Chiaki is more brawn, but is later revealed to have a sensitive, artistic side when it is revealed he came back in time to see a painting.

Auntie Witch – This character understands what time leaps are, and in the narrative she functions as the character who explains to the viewers how the science works in this story. In fact, to a modern audience, this form of exposition feels like a bit of a hack once you’ve given it a bit of thought. But it’s far from unusual in film.Michael Caine functions this way in Interstellar and various other films by that filmmaker.

In the film it is not explained how Makoto even knows the Auntie Witch. This is where it helps to have some background on this classic Japanese story — the Auntie Witch is meant to be the protagonist of the original 1967 novel (though she does look a little young… She should be the age of a grandmother by 2006.)

Opponent

If this were a Hollywood production I’ve no doubt the group of airhead junior girls — the volunteer club — would have been depicted as clearcut love rivals in the mean girls tradition. The Japanese dynamics are a lot more nuanced and, in my opinion, more realistic. The girls in this story are not outright rivals — they are interested in the same boys (for varying reasons) but they cheer each other on and take their share of ‘love hits’. Theirs is a spirit of sharing and caring for each other. In this story, Makoto finally declares her interest in Chiaki and her love rival backs off before her crush even begins. All of this is far more interesting than your usual mean girls crap.

But the writers of the Pixar film Inside Out, a hugely successful story, say that the most relatable villain is yourself, or nature:

I came on Inside Out, Pete [Docter] was not leaning towards any villains. I think at one point there was the idea floated that those Forgetters are villainous in trying to grab the core memories so Riley would forget them. But it just never really caught Pete’s imagination and it really wasn’t what he wanted to focus on. And as a storyteller, I love that more complex idea. And so Pete Sohn [the director of The Good Dinosaur] decided very early that you’ll have characters that Arlo will come into conflict with and challenge him for sure. The villain is, if there is one, you want it to be nature. The movement of nature and the idea that nature is something to be respected—that was the antagonist of this movie.

Interview with Pixar writer

Who is the villain in a Japanese high school story, in which the bullies versus the good kids tends to be less stark? Could it be that the villain in this story is time itself, or the nature of the magic inside the time-leaping device?

Mystery

In this film the romantic mystery is presented quite late. Until we overhear some speculation between students we have no idea that Chiaki is new to the school and that no one has any idea where he came from.

The magical part of the mystery is: What is this little device Makoto found in the science lab, how does it work and what can it do? We watch her figure it out.

Changed desire and motive

When the story began Makoto just wanted to remain childlike, but after almost being (almost?) killed by the train Makoto realises something weird is happening. She wants to find out what.

First revelation and decision

Her aunt who works at the art gallery clears everything up for her. Makoto can put this tool to good use and help her to arrange her life in such a way that she is ready to move on.

Plan

Makoto will use this time-leaping skill firstly for inconsequential things, like getting more time in the karaoke booth and avoiding embarrassing situations socially at school, and redoing maths quizzes. The Witch Auntie is glad that she’s only using her ability for inconsequential things, but asks Makoto — and therefore also asks the viewer — if the outcome of changing time is really as inconsequential as it seems.

Gazing out onto the river she realizes she can do anything with this trick. The setting of the river is a metaphorical juxtaposition — in fact, you can’t stop the flow of time. At least, you can’t stop things happening to people, even if the victim is not you.

If you keep track of the timeline, or even just the set pieces, you will realize that Makoto discovered her powers, got asked out by Chiaki, and had her heartfelt goodbye at the exact same spot at the river, at the exact same sunset. In fact, the entire movie never progressed beyond that last sunset until that last goodbye, which is when everyone finally moves on and the Airplane of Love beautifully tops off the ingenious Three Parts of the Story created by Makoto’s choices at this single junction in time.

TV Tropes

Opponent’s plan and main counterattack

The opponent is the magic itself, which does not always do what Makoto hopes it will.

When Makoto saves herself in cooking class, another boy gets into trouble instead, and this leads to a whole lot of bullying. Makoto can deflect disaster from herself, but it seems someone still needs to be sacrificed, according to the laws of this magic.

Drive

Makoto is determined to make the time-leaping work. Sometimes it means trying time-leaps again and again to get a situation right, and sometimes it means leaping back much further than she has energy for. This is basically a version of the very Japanese trait of trying again and again until you get it perfect (a la The Karate Kid).

Attack by ally

Auntie Witch continuously asks Makoto questions which lead to Makoto’s character arc. She’s talking to Auntie Witch, and tells her everything in her life has been fixed. Auntie, in her greater wisdom, asks if someone else may be suffering due to her good fortune.

After these trifling time leaps turn into something more serious — Chiaki’s declaration of love — Makoto talks to her witch auntie about her love life. The auntie advises her to be honest with Chiaki rather than ignore that he ever told her how he feels about her.

Later in the film auntie witch advises Makoto to go out with Kousuke, since he’s always the one helping her out. Auntie Witch points out that Makoto has ‘been playing all sorts of mind games with people.’

Auntie says, “I wonder who was able to create such a beautiful painting when it must have seemed like the world was coming to an end.”

I can’t be bothered putting them all in order, but each time Makoto has a revelation, it happens in Auntie Witch’s office, or as a direct result of her sage advice.

Apparent defeat

The crossroads/riding bitch scenes replayed over and over teach Makoto that she can’t change Chiaki’s feelings for her. She leaps back through time in order to give herself time to think of a good response and get out of the awkward romantic situation. To her disappointment it’s not as straightforward as she’d thought because the conversation is slightly different each run through. In the end, she leaps back to the crossroads and refuses to be dubbed home at all.

Things are going wrong now – Chiaki is blamed for the fire in food technology class and Makoto knows Chiaki likes her now, though Chiaki has no recollection of having told her he likes her (because he hasn’t). He wonders what’s up with her avoiding his gaze.

Now she avoids him entirely. (Montage sequence)

Chiaki looks for Makoto in vain and concludes he’s pissed her off.

Obsessive drive, changed drive, and motive

Makoto decides to use her time leaping for good.

Second revelation and decision

Magical revelation: She works out her time leaps are limited in number. That’s what the number on her flesh means.

Plans Never Go To Plan

The important thing about plans made by main characters in stories: The plan never works out the way they expected.

Audience revelation

Chiaki reveals that he came from the future.

There is a series of montage stills with muted colours and lots of muted red, including a red balloon in the sky.

He explains that he had a device that let him time leap but he lost it. He eventually found it in the science lab but it was all used up.

He came back because there was a painting he desperately wanted to see “White Plum Two Camellias’. In his time the painting has already been destroyed. This is the only place he can find it.

Now he’s unable to go back to his future time. He used up all his time leaps stealing the bike Kousuke was supposed to ride.

Kousuke and the girl did die once at the train crossing. He had to come back because Makoto was sobbing and blaming herself for it.

Chiaki has decided to stay here because being with Kousuke and Makoto has been so much fun. He rode a bike for the first time, discovered how enormous the sky was, and has never seen a place with so many people.

Makoto asks about the painting and its connection to the future. As they walk through the statue crowd, Chiaki explains that the painting is getting restored and he’ll be able to see it soon. She wants to take him to see it, with Kousuke.

But he’s not meant to tell anyone in the past about time leaps.

Third revelation and decision

Magical revelation: Makoto ponders this one at home then realizes one of her leaps has come back (from the number on her arm.)

She’s now convinced if she goes back far enough, Chiaki can get a leap back too. (I don’t quite understand this logic.)

We see a montage of times the three of them have spent together, with a staticky filter in muted colours. There’s a Japanese love song playing.

She’s back in the science lab with the notebooks and refinds the time leaping device. This time she doesn’t use up the device. This time she tells Yuri she really likes Chiaki a lot. Yuri is disappointed but says she thought so. She advises Chiaki to go see Chiaki and tells her, ‘Time waits for no one.’ This time she invites the volunteer club to play ball with them, so Kousuke can organically get to know the girl.

Plan to stop anyone from getting killed on her bike: She says he can’t borrow her bike unless he pays her five thousand yen. There is a scene where we see her running flat out. A lot of films show this scene when the main character has had a revelation. It’s meant to show that they’re resolving to do something, forming a plan, and that this plan is going to take a lot of effort to achieve.

Romantic revelation: She realises she likes Chiaki as more than a friend and if she doesn’t tell him, she’ll lose him.

“Why couldn’t I take what he said more seriously? He wanted to have a difficult conversation and I couldn’t handle it.” She goes to the roof and cries (a classic Moses scene) because big revelations in films often take place somewhere high.

Gate, gauntlet, visit to death

Makoto’s time leaps need to get really dangerous as she jumps from higher places in order to leap further back in time to change ever having used up the leaps in Chiaki’s device.

But the real visit to death is the near death experience of Kousuke and Yuri as Kousuke takes Yuri on his bike to get an X-ray after one of the horsing-around kids lands on her (instead of on Makoto, as happened earlier.)

Her number has changed to zero. She realizes she’s used up all her leaps. But just then he zooms past. She drops the phone. “I need to borrow your bike a bit longer!”

Now the situation is dire – she can’t catch the two of them. She falls over trying, and is covered in scratches and bruises. Kousuke and his new gf are thrown into the path of the train.

We see the image from the very beginning of the film, with the red numbers on black. (Symbolic colours — red = blood, black = death.)

Makoto yells ‘stop!’ and everything does freeze. The only two people who haven’t frozen are Makoto and Chiaki, who has her bike with its broken brake. It turns out Chiaki can time leap too.

Battle

I’ve noticed that although films always have a big struggle scene, the big struggle is often a transferred one. I mean, the big struggle Makoto faces is an inner psychological big struggle. But the literal fight the audience sees played out on the screen in front of us is actually the fight between the boy who ended up setting fire to his pan in food technology after Makoto changed her own fate, and the boys who have decided to taunt him because of it, taunting him with the fire hose. Finally this boy retaliates — goes off the edge — and in the first round of reality the bullied boy, Takase, who has a bowl of noodles on his head, throws the fire extinguisher at Makoto. Chiaki steps in front of her to save her. Makoto leaps back through time so the situation plays out differently, and Takase ends up throwing the extinguisher at Yuri, injuring her shoulder instead.

Anagnorisis

Makoto feels very bad that by changing fate she has lead to the injury of her best friend. Not only that, Chiaki is now going out with her best friend instead of her. She realises that this would never have happened had she accepted Chiaki’s declaration of love in the first place.

(Makoto promises Yuri if the incident leaves a scar she’ll fix things, but doesn’t explain how. Perhaps this is where Chiaki realises Makoto knows all about time leaping.)

Moral decision

Kousuke and Chiaki are playing baseball together. Makoto has told Kousuke Chiaki has gone to study abroad. We know this isn’t true because it was Makoto’s plan for herself.

Makoto has made a decision about her future. “It’s a secret.” She looks up at the towering cloud. I hope she’s not pinning her hopes and dreams on a future with a boy. (It’s possible that in the 1967 novel, that’s exactly the track the female protagonist will take, and in the setting of respected housewives, it’s not such a bad one, either.) But we never get told whether our young, modern Makoto chosen the arts or science track, or is just going to hang about waiting until she can reunite with the boy.

Makoto changes time until she can meet Chiaki in the baseball field. She hands Chiaki the device he dropped. She gives Chiaki back the device and when it explodes in the palm of his hand he gets an extra leap appear on his arm.

Makoto tells Chiaki she’ll work out a way to preserve the special painting he loves – “It’s not going to get lost or burned.”

Chiaki says goodbye. He tells her not to get herself hurt by jumping out in front of things. “The old look before leap thing definitely works.”

Chiaki disappears and by coincidence a couple who look very much like them on a bike sails past. She cries alone with the sunset in the background but then Chiaki rejoins her and gives her a hug. “I’ll be waiting for you.”

“Okay, I won’t be long. I’ll come running.”

A jet leaves a contrail across the sky in a long shot then fades to black, with red numbers.

New situation

Makoto is now playing baseball with the volunteer club juniors, and the audience surmises that she will be friends with them rather than almost-rivals. The audience knows that Kousuke will end up going out with Kaho (pronounced incorrectly as ‘Ka-who’ in the English dub), the girl with the crush on him, so he is sorted romantically for now.