The Wind In The Willows is an Edwardian (1908) novel by Scottish born British writer Kenneth Grahame. This book is an example of a story from the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Idyllic settings were popular at the time. Idylls remained popular up to and including A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh books (written 1924-1928).

WHO IS THE AUDIENCE?

Peter Hunt argues that The Wind In The Willows , despite its talking animals, isn’t a children’s book. For starters, we’re not really meant to read these animals as animals.

“That? O, that’s just the Wild Wood,” said the Rat shortly. “We don’t go there very much, we river-bankers.”

The Wind In The Willows

“Aren’t they — aren’t they very nice people in there?” said the Mole, a trifle nervously.

Toad is not a toad, Toad has hair. It’s mentioned a couple of times.

He shook himself and combed the dry leaves out of his hair with his fingers; and, his toilet complete, marched forth into the comfortable morning sun, cold but confident, hungry but hopeful, all nervous terrors of yesterday dispelled by rest and sleep and frank and heartening sunshine. […]

[Toad] sang this very loud, with great unction and expression; and when he had done, he sang it all over again.

Then he heaved a deep sigh; a long, long, long sigh.

Then he dipped his hairbrush in the water-jug, parted his hair in the middle, and plastered it down very straight and sleek on each side of his face; and, unlocking the door, went quietly down the stairs to greet his guests, who he knew must be assembling in the drawing-room.

The Wind In The Willows

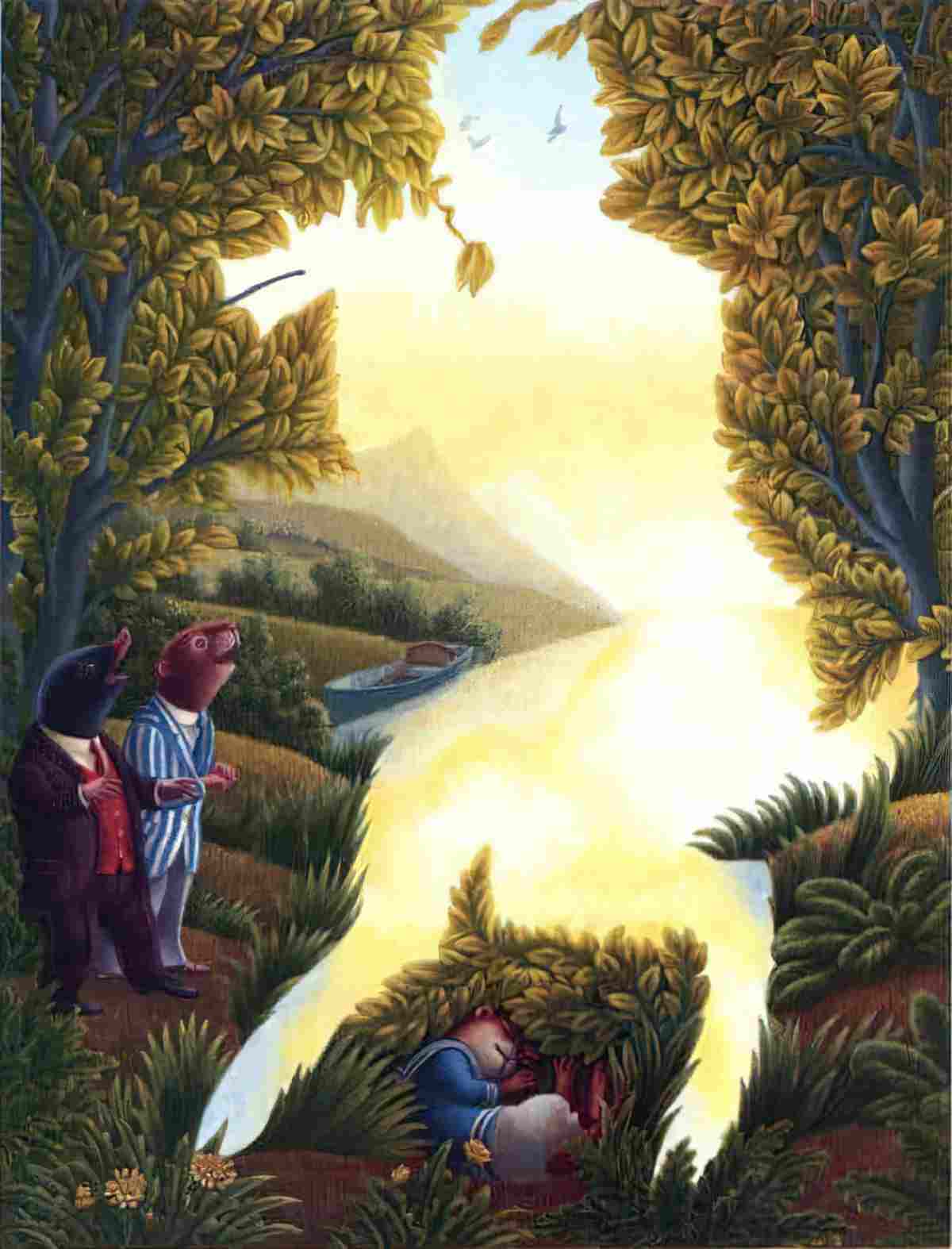

Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows asks the same question – person or animal? – but the evidence is more complicated. The story of Mole and Water Rat begins with characters that are clearly animal, and it only slowly dawns upon the reader that it’s the other way around. The animals here are stand-ins for people, and very recognizable people, at that. Otter is the scrappy, cockney city chap; Badger your introverted, gruff old country fellow; Toad the landed gentry whose money has gone to his indulgent head. And Mole lives in his under-hill home, which is no muddy animal lodging,but instead a tidy, thoughtfully-decorated . . . well, let’s be honest: hobbit hole.

Rebecca D. Martin

The unseen narrator positions himself as ‘Other’ to the characters in this work, without actually calling readers ‘people’. If he speaks of the animals as ‘people’, this may be considered a slip up on his part. (At other times he clearly refers to the animals as animals.)

We others, who have long lost the more subtle of the physical senses, have not even proper terms to express an animal’s inter-communications with his surroundings, living or otherwise, and have only the word ‘smell’, for instance, to include the whole range of delicate thrills which murmur in the nose of the animal night and day, summoning, warning, inciting, repelling.

The Wind In The Willows

Animal-or-person question aside, in line with Hunt’s assessment about the ideal audience of this work, I didn’t appreciate The Wind In The Willows as a child. These animals have childlike qualities, but they are adult archetypes, recognised best by adults.

Mole is not really animal, but the Every Man, a low mimetic hero to use Northrop Frye’s terminology.

My love for The Wind In The Willows began as an older teenager, when our mother took us to see the play. A.A. Milne (of Winnie-the-Pooh fame) adapted part of it for stage as Toad of Toad Hall back in 1929 and it’s very funny. As you can tell from the title, the character of Toad takes centre stage. He’s a wonderfully camp character. I guess this makes this story ‘collegiate’.

I have come to believe The Wind In The Willows has two separate strands, one for (Edwardian) children (used to a slower pace), the other metaphorical, which only a post-adolescent audience will appreciate. The Wind In The Willows is your ultimate dual audience work, which partly explains its longevity.

Other works ‘children’s stories’ with a ‘kid’ layer and a ‘sophisticated’ layer:

THE UTOPIAN SETTING OF THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

In common with Charlotte’s Web, The Wind in the Willows takes place in a pastoral, Arcadian setting. Arcadian/pastoral stories commonly contain a message about the brevity of life as a subtext.

Modern commentators extrapolate that Kenneth Grahame was gay (or bi- or pan-). The first to publish the idea that Kenneth Grahame was gay: Graham Robb. Peter Hunt agreed (possible paywall). We’ll never know for sure sure, partly because Grahame’s only son died young, leaving no descendants.

Here’s what we do know: Kenneth didn’t live with his wife and son. Instead he lived in London with an artist and set designer named Waldford Graham Robertson, who was close friends with Oscar Wilde. Another LGBTQ+ connection, Constance Smedley, helped see Wind In The Willows to publication.

I’m wary of reading too much biography into fictional work, but this does lead to the theory that Kenneth Grahame created Wind in the Willows as a cosy gay haven in which male characters could enjoy intimacy with each other free of bigotry and strictly enforced gender binaries. This knowledge of Grahame’s living arrangement has indeed altered my adult reading of The Wind In The Willows. (For the better.)

Some commentators have pointed out similarities between Wind and the Willows and Frog and Toad, by Arnold Lobel. Through a modern lens, frog and toad are clearly intimate. (Audiences at the time probably took a Winnie-the-Pooh approach and coded the animal characters as genderless and non-sexual.) But through a queer lens, I would like everyone to consider the split attraction model if considering the characterisation in stories such as Frog and Toad and The Wind in the Willows. We need to open space in our view of human relationships for queerplatonic relationships.

CLASS ISSUES

Both Lobel and Grahame created a similar homosocial (possibly homosexual) utopia in their children’s books, but some have said that’s where similarities end. If Grahame is creating a genuine utopia — itself debatable — Grahame’s idea of the perfect refuge seems aristocratic and classist. This interpretation of the text suggests that even in Grahame’s imagination, rich men must inevitably control poor men. But is it really the case that Grahame wasn’t able to think outside the economic caste of the real world, immersed as he was in the Edwardian glitterati of London?

COSINESS AND THE HOME

Perhaps the reader is partly responsible for a classist take. Perhaps the kind of resources which create cosiness just happen to be the kind of resources only afforded to aristocratic Britons. This story world is undoubtedly hygge by any definition, and when Badger says ‘You’re entirely your own master’, does Grahame not mean that for everyone? Sure, Grahame has created a utopia with class distinctions, but in order to critique a system, an artist must first show it:

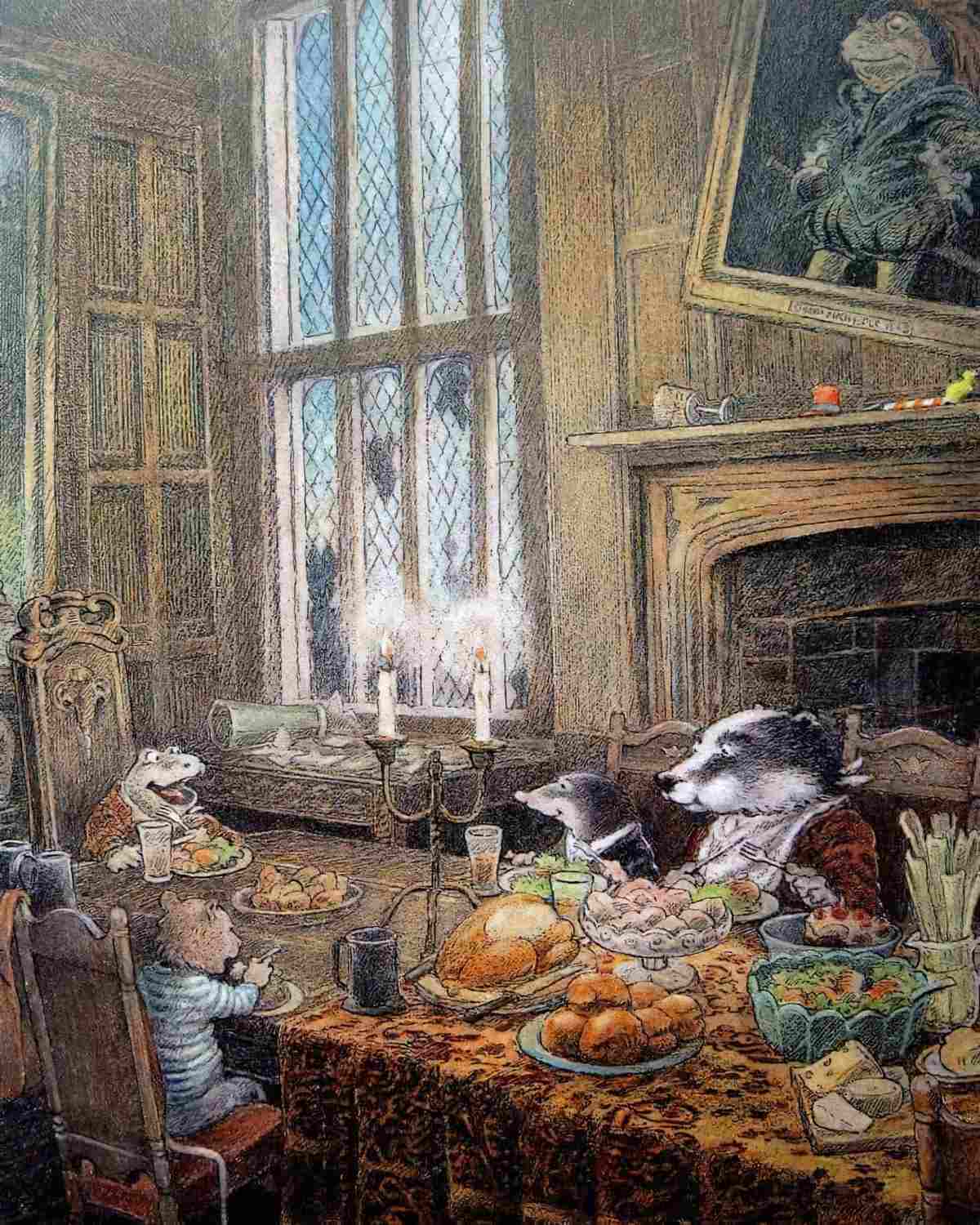

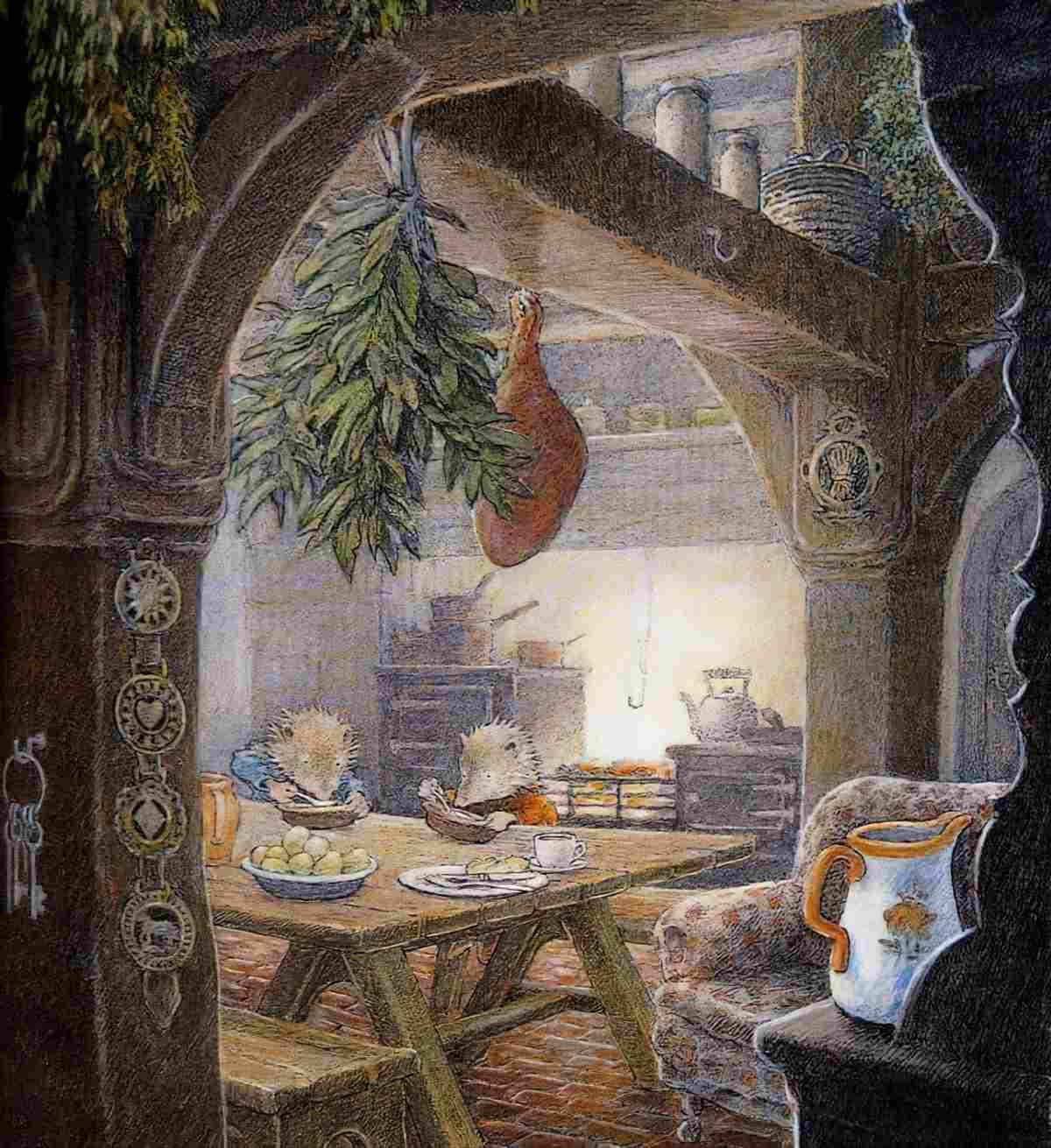

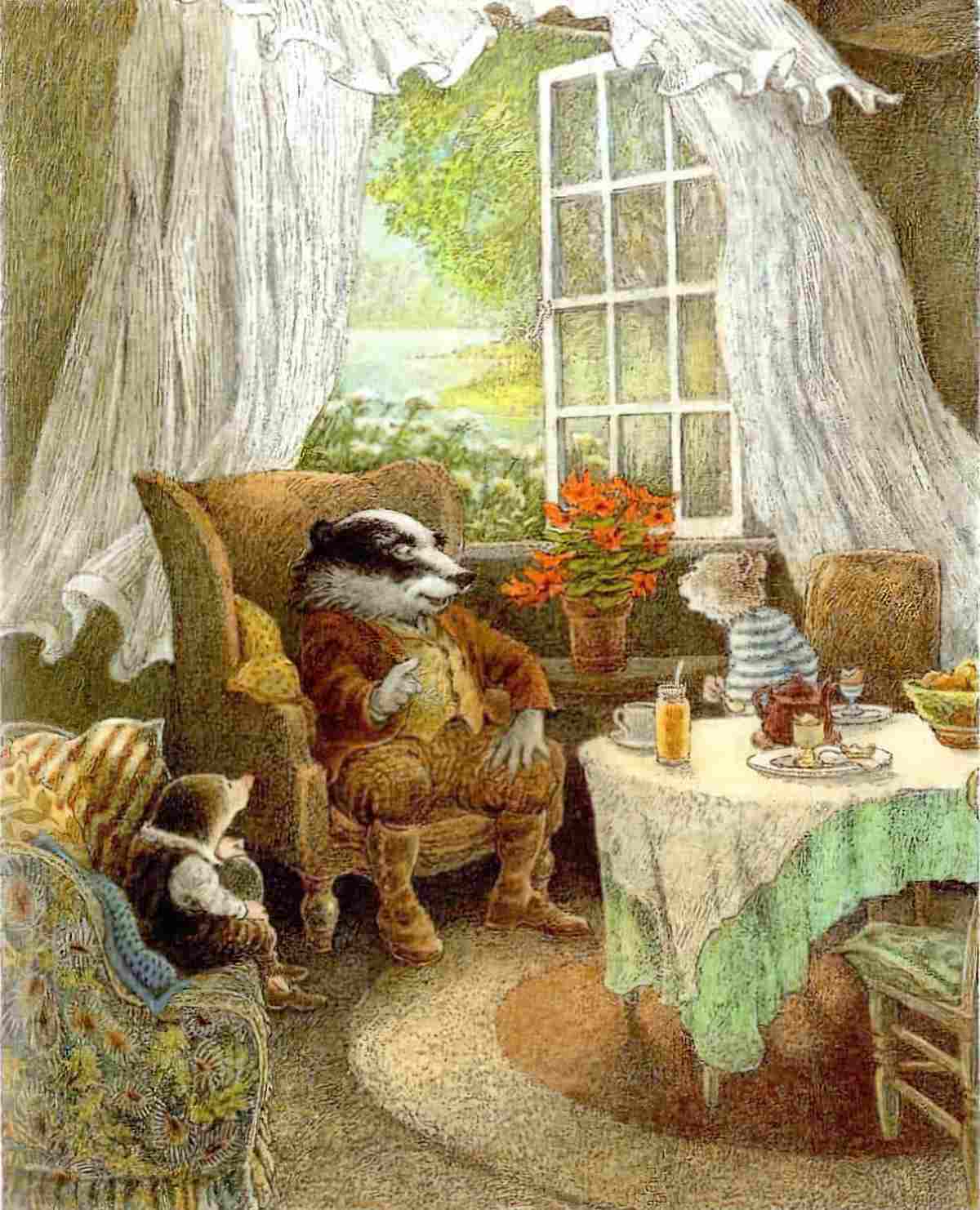

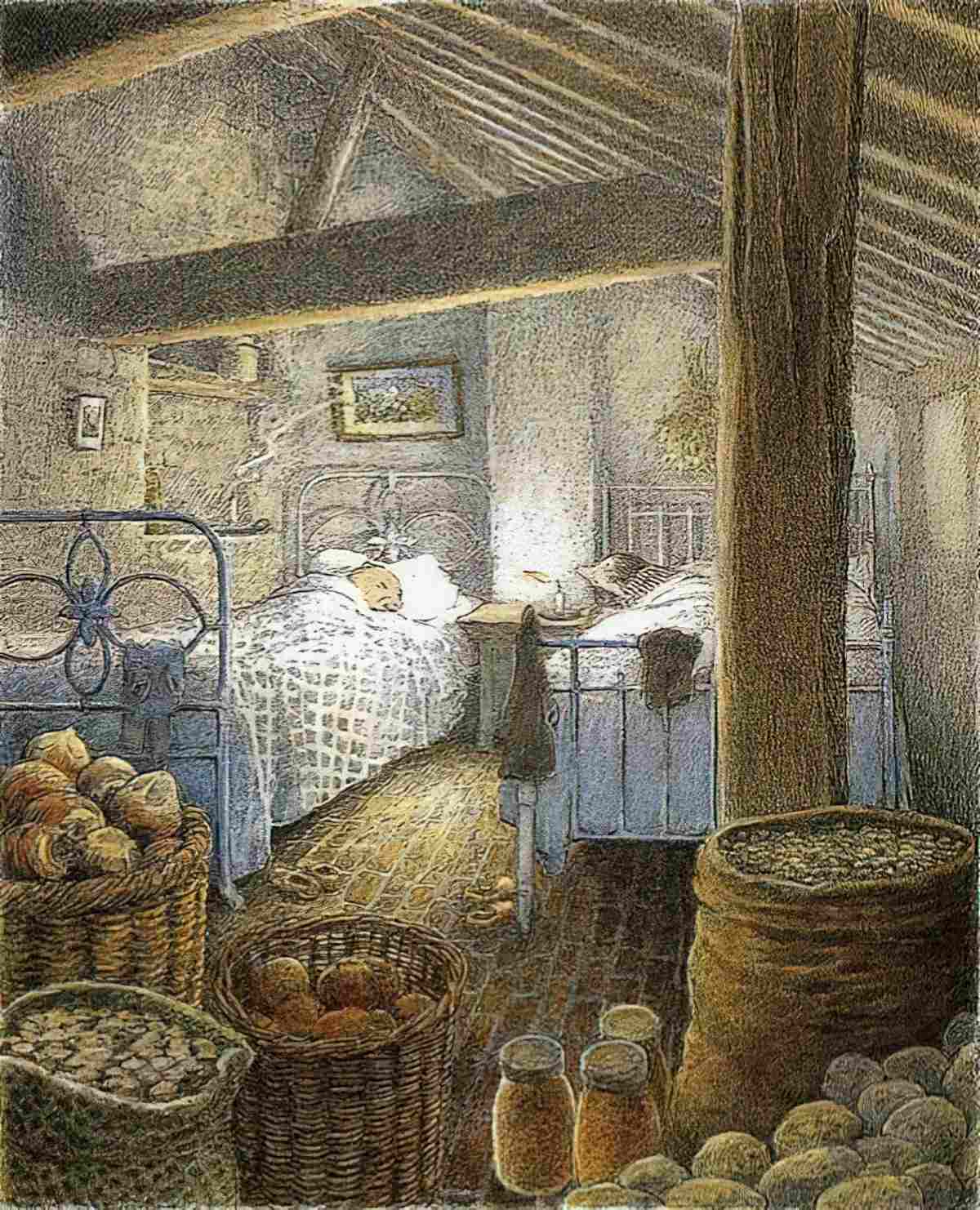

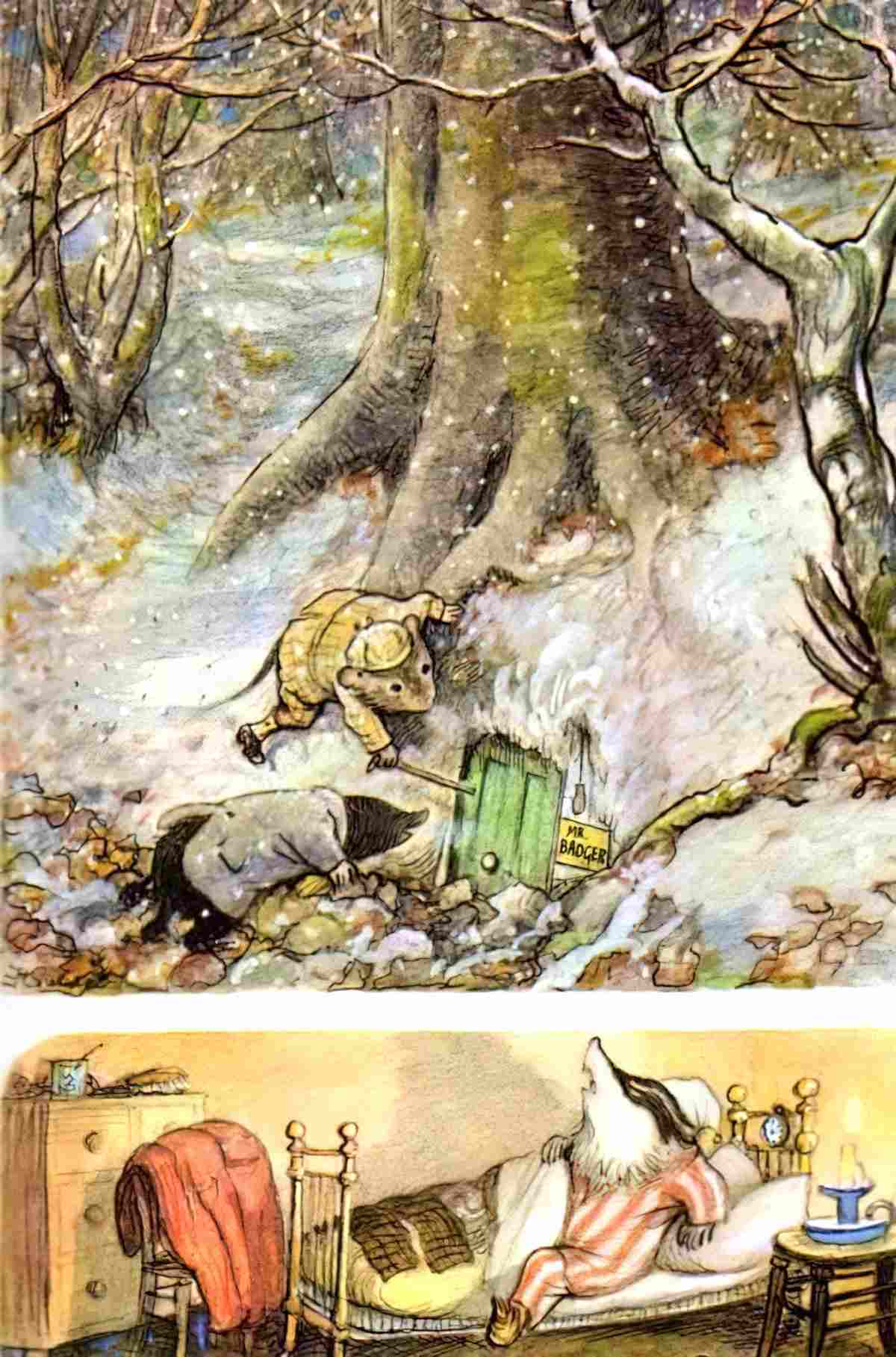

One of the real great examples of snugness occurs in The Wind in the Willows when Mole, after having been lost and snowbound in the Wild Woods, finally finds his way to Badger’s cozy, underground abode. The vision Kenneth Grahame gives us of Badger’s welcoming kitchen, the merry fire that greets the shivering Mole, that simple but welcoming place with its baskets of eggs and smiling plates—all these suggest the very picture of the snug abode and how snugness is a kind of friendly patina laid down on top of brute objects, how snugness is a spiritualization of feelings added to a place.

Felicitous space is often enclosed and protected; sounding very much like Robinson Crusoe talking about his stockade, Badger says of his underground home: “Nothing can happen to you, and nothing can get at you. You’re entirely your own master.” You might also think, in this regard, of the familiar childhood drawing of the “happy house”: a squat home very much rooted in the world, with eye-like windows, a welcoming door, and a chimney with smoke pouring out to indicate it is inhabited; and, of course, the sun happily shining on all of this.

Jerry Griswold

THE WEIRD ANIMAL HUMAN COMBO

Kenneth Grahame sets up a world which seems, at first, to be entirely inhabited by talking animals. But then — surprise! — Grahame springs humans on us. For some readers, this jars. Weren’t these animals meant to be the humans, like in Planet of the Apes? I mean, these ‘animals’ keep a bird in a cage, which is weird… animals keeping animals. Ahem. Look at that ham hanging from the rafter. Toad thinks the gaoler’s daughter might even fall in love with him, making this cross species thing a bit too much for some.

The story works best if you’re able to accept this strangely ‘peopled’ world, and laugh at the inherent humour of toads who grow hair, and who are animal one minute, human the next.

I do find the following passage a bit strange. The writer in me thinks Grahame may have originally intended to ‘people’ his world with only talking animals, but that actual humans were too useful for the plot. He may have subsequently forgotten to edit this passage out:

[V]ery long ago, on the spot where the Wild Wood waves now, before ever it had planted itself and grown up to what it now is, there was a city—a city of people…”

“But what has become of them all?” asked the Mole.

“Who can tell?” said the Badger. “People come—they stay for a while, they flourish, they build—and they go. It is their way. But we remain…”

Then again, Kenneth Grahame may have meant absolutely every word that was published. He absolutely meant to leave in chapter six, when subsequent editors often nix it. (I’m not in favour of willy-nilly nixing, even if I do happen to suspect something may have been left in by mistake.) Also, I’m sure others have theories about what that passage means. Probably something to do with the four stages of social evolution — humans came out of the trees, we’re all part of one big evolutionary experiment. That sort of thing. I guess it could mean that.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by science journalist and author Gaia Vince to talk about her newest book, “Transcendence: How Humans Evolved Through Fire, Language, Beauty, and Time.” They discuss the importance of viewing the human evolutionary story as one that is inextricably linked with culture and kinship, and so much more.

Social Evolution w/ Gaia Vince

The Wind In The Willows may feel universal to Westerners now, but this story is to other cultures unusual at first meeting:

1 June: When Jeremy Sams directed The Wind in the Willows in Tokyo he had many practical problems … the cast were anxious to know about other characters like their own – other Moles, for instances, other Toads. ‘But there are no others,’ explained Jeremy. This the actors were unable to grasp or the fact that The Wind in the Willows was not compared. All the plays in Japanese theatres are genre plays, variations on a theme or set of themes; the idea that a play might be unique seemed to them very strange indeed.

Alan Bennett, from a diary entry, excerpted from Untold Stories

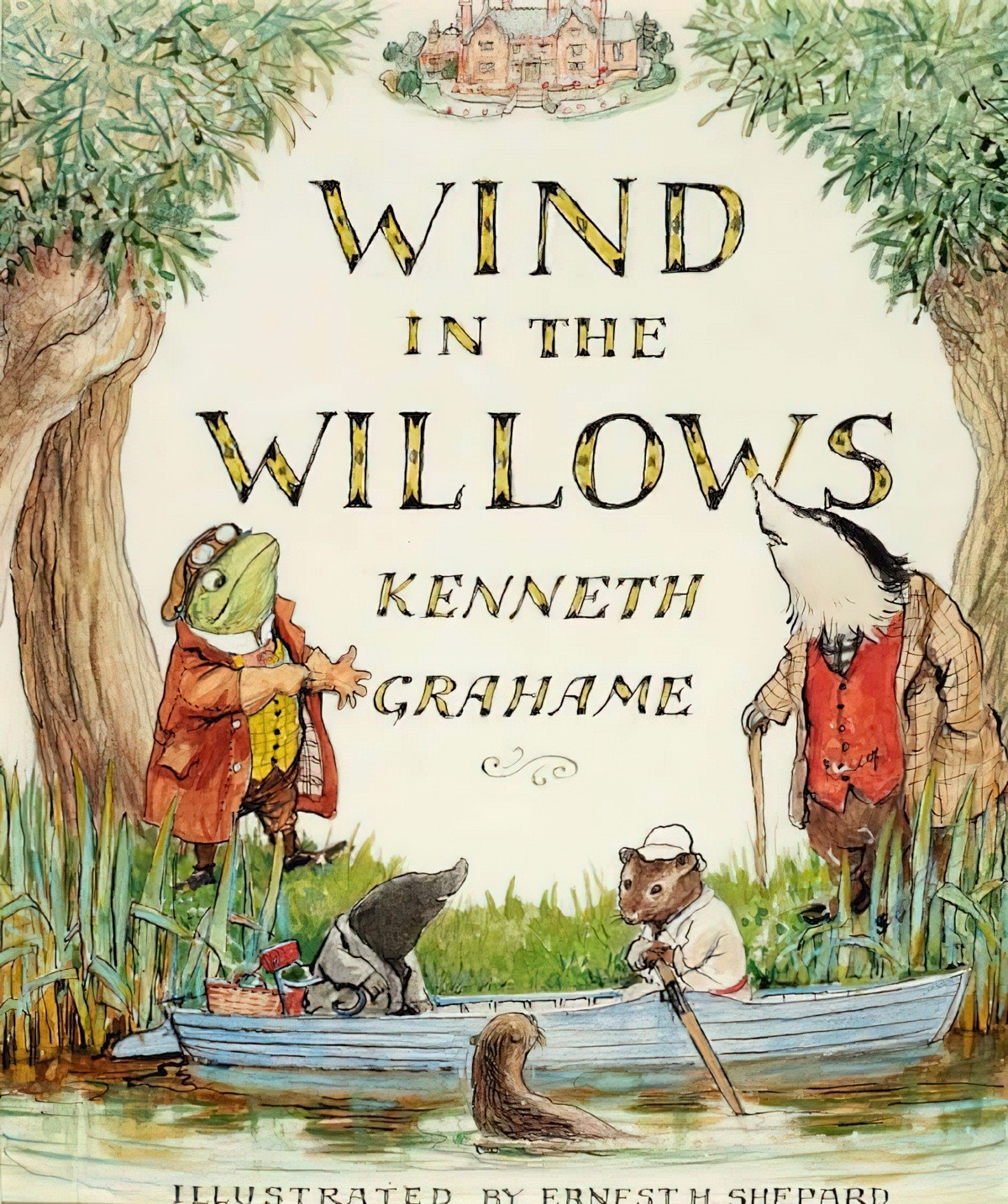

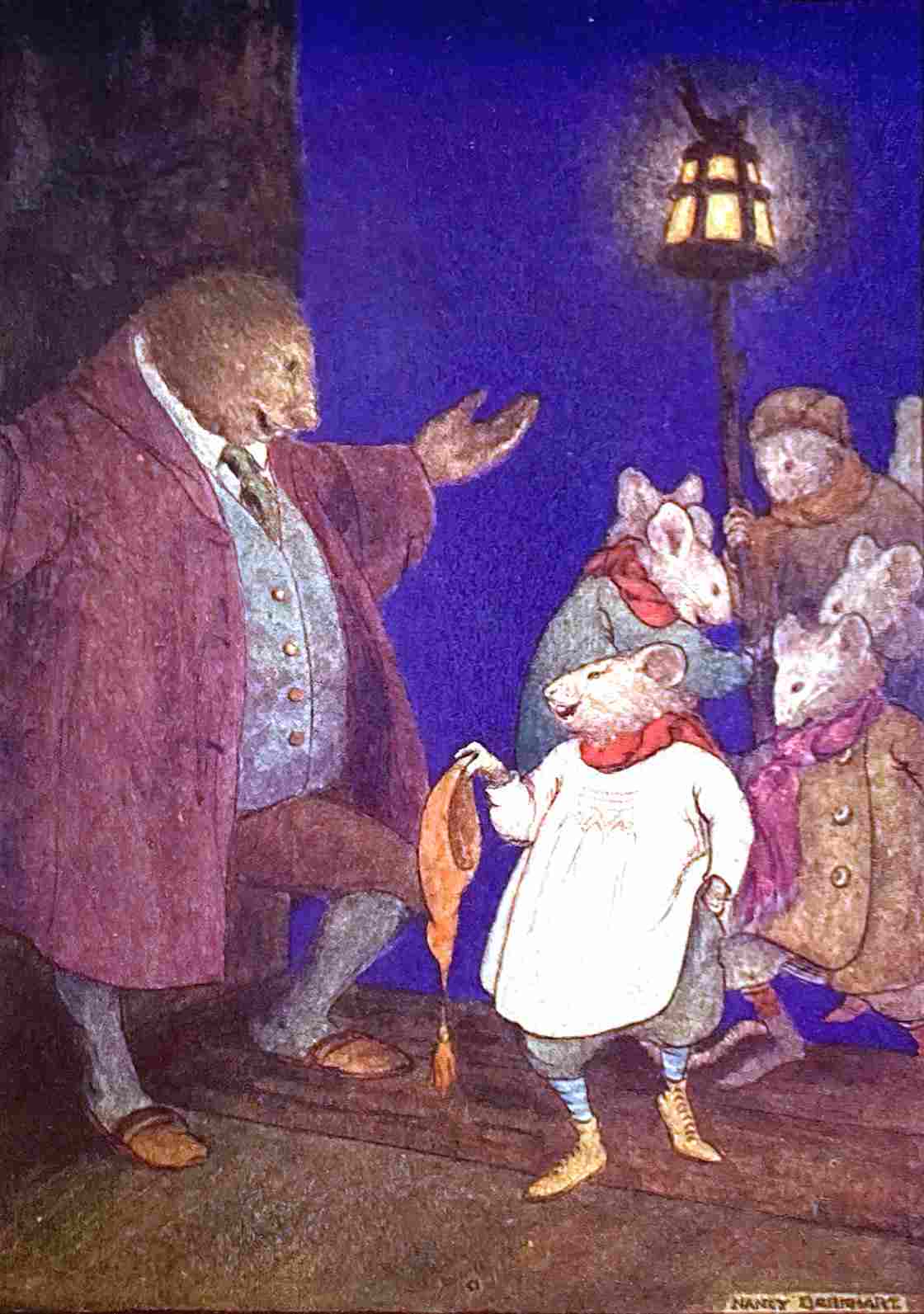

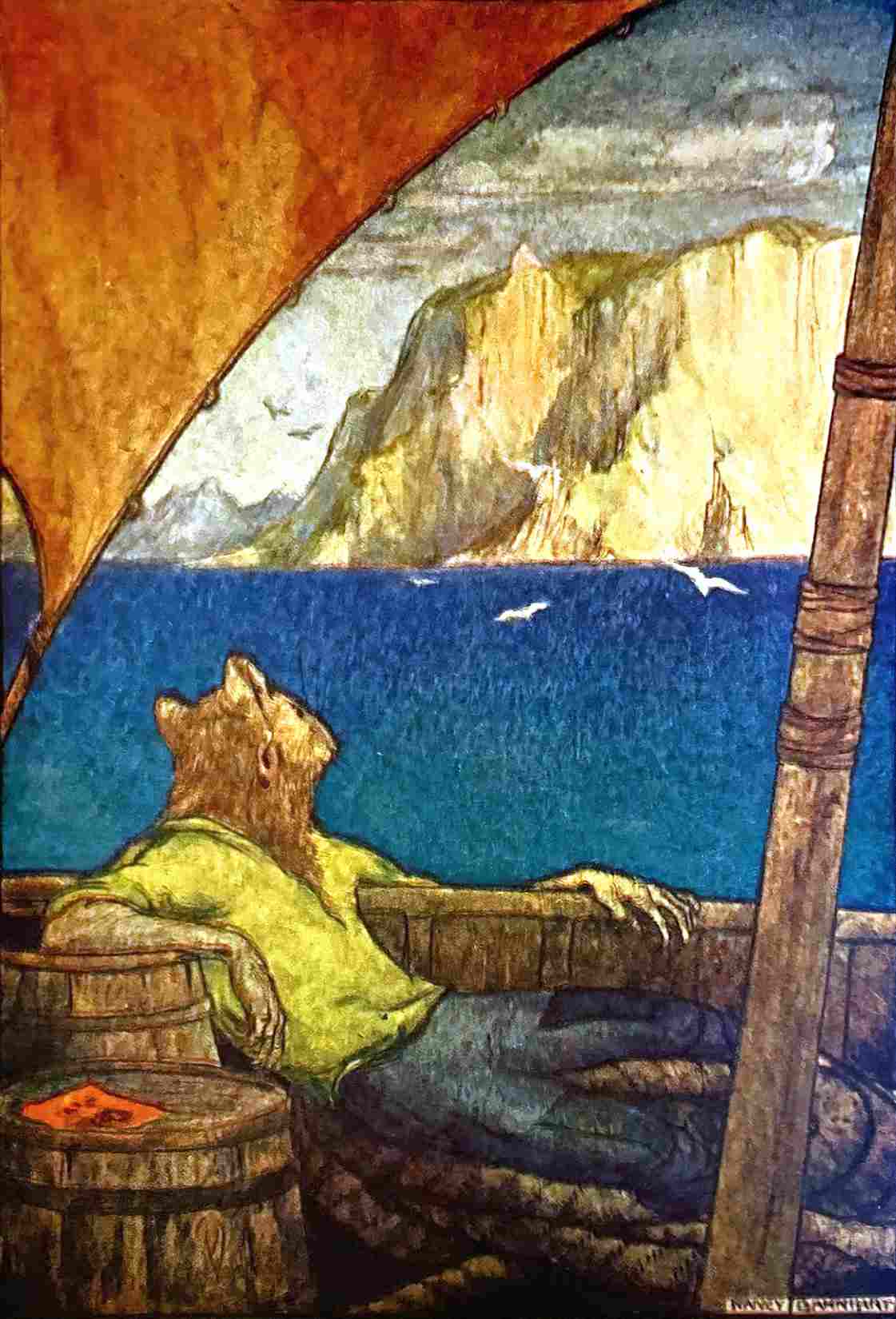

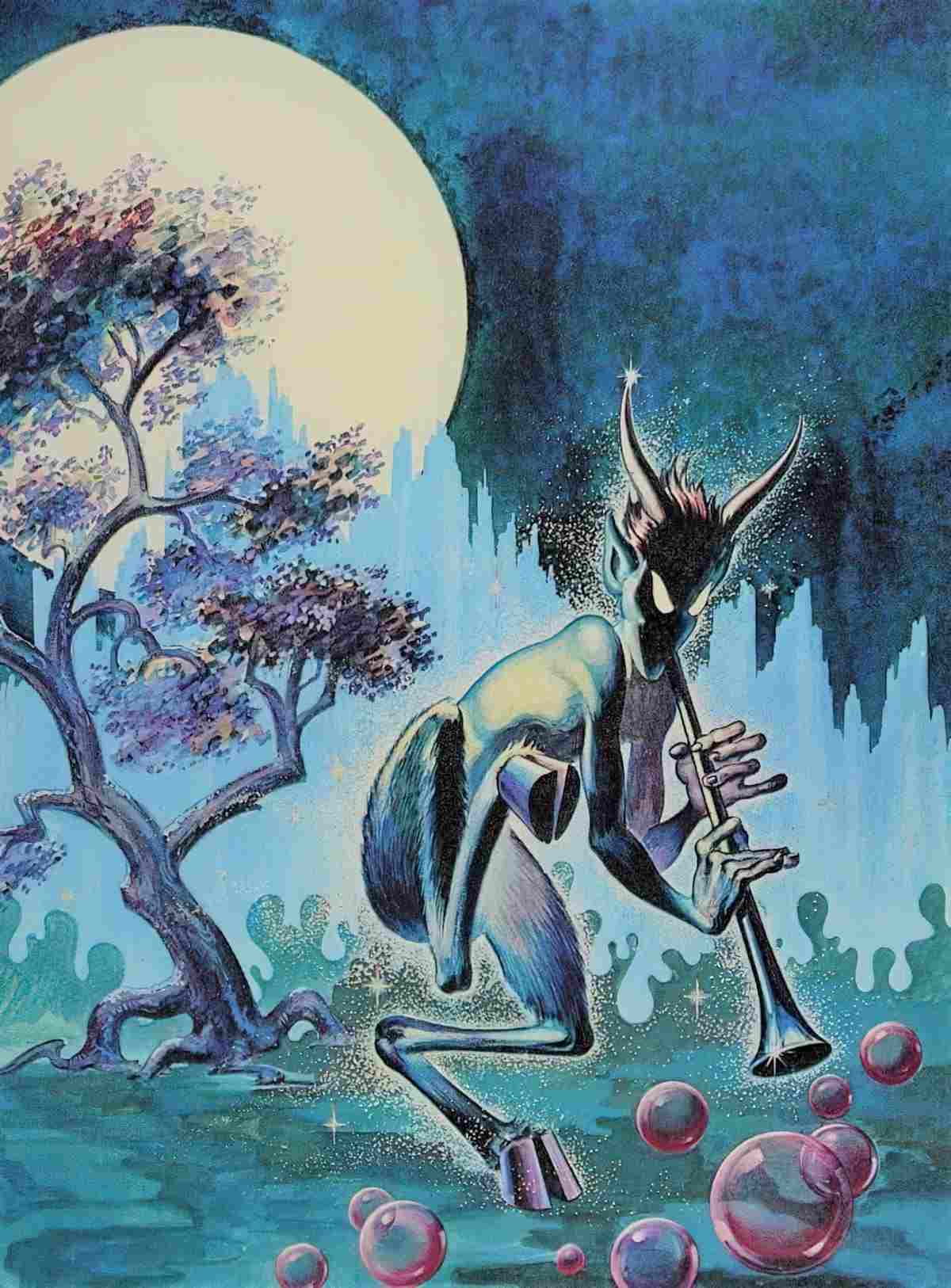

ILLUSTRATORS OF THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

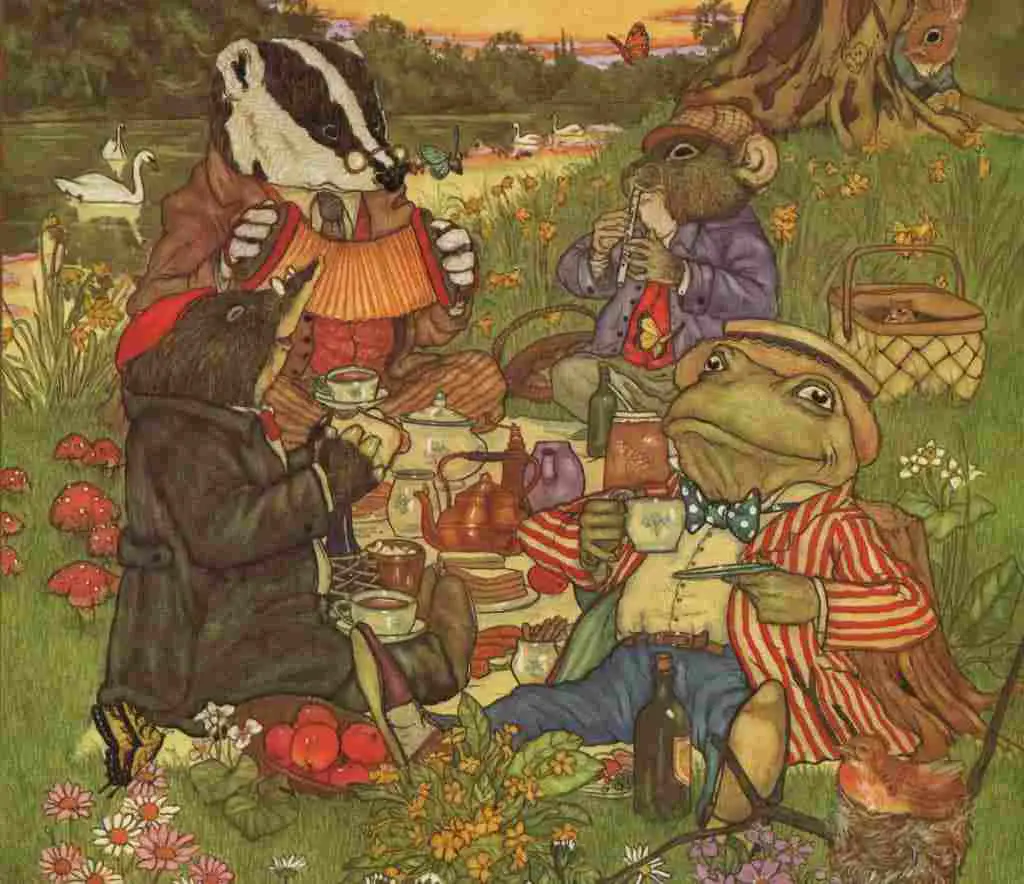

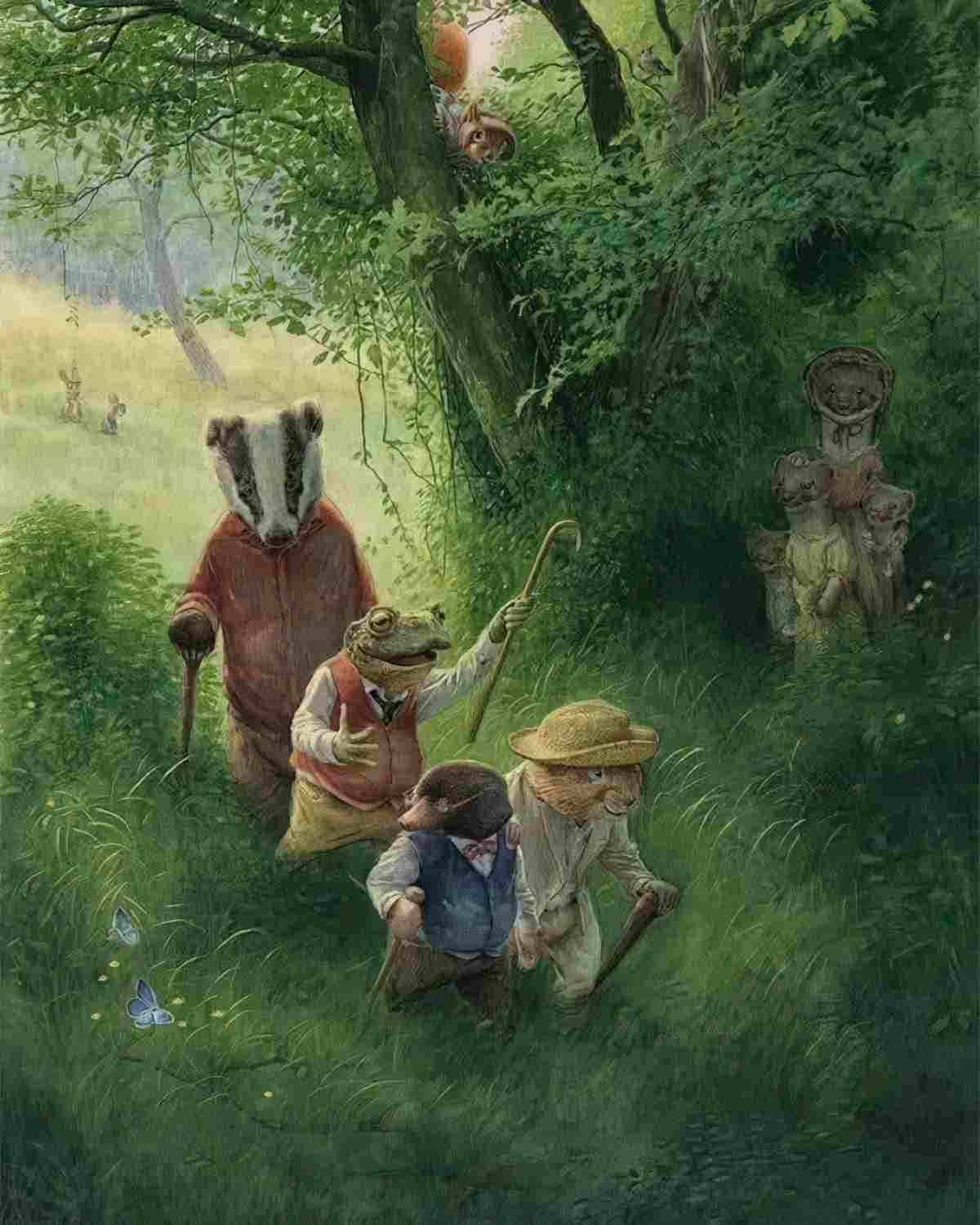

The Wind In The Willows is a classic that illustrators love to work on. Every time a new edition comes out with a new illustrator I think, who can possibly add anything to the corpus of existing illustrations, and then I’m newly impressed.

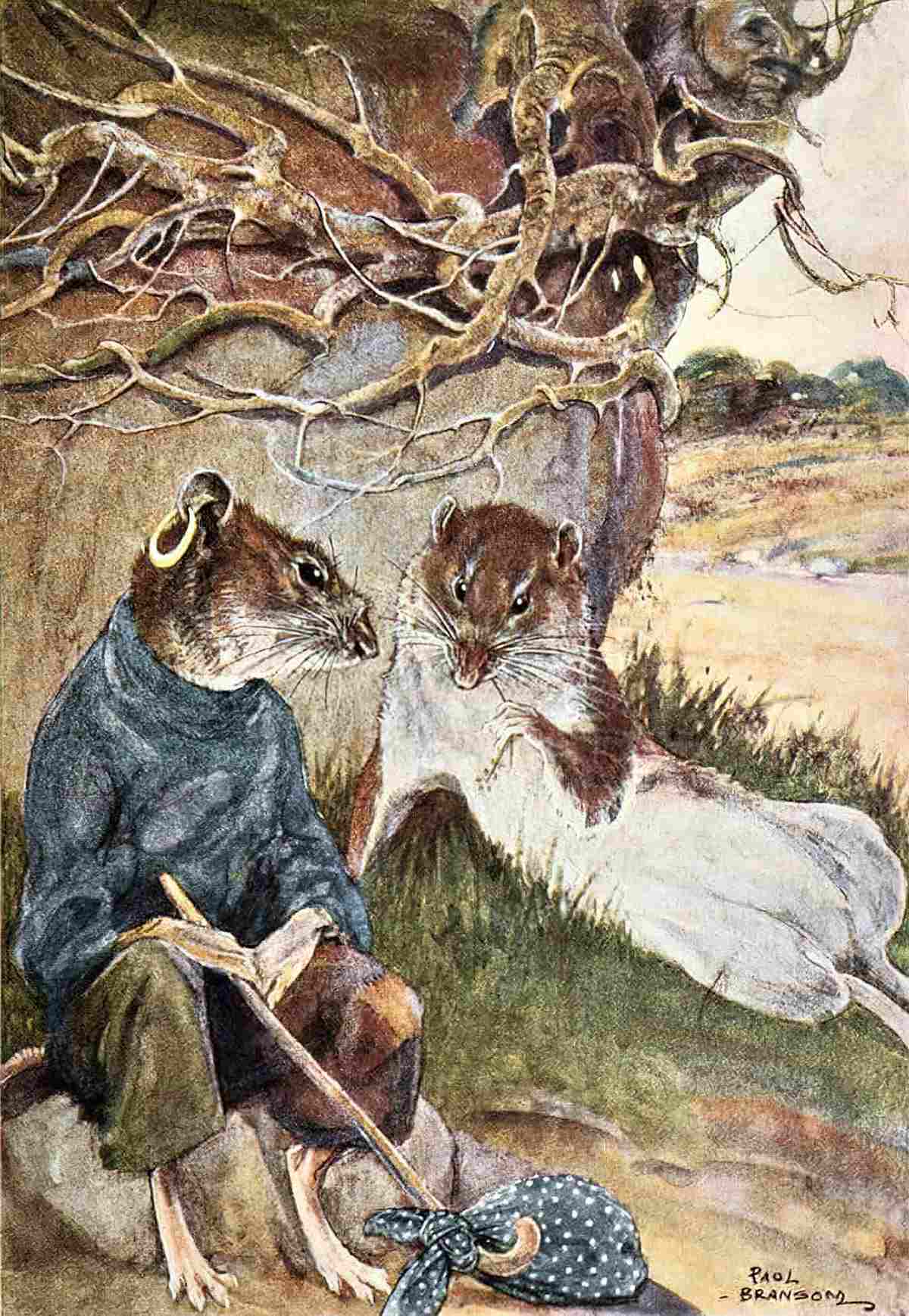

An early illustrator of The Wind In The Willows was Paul Bransom, enjoyed by children through the first World War.

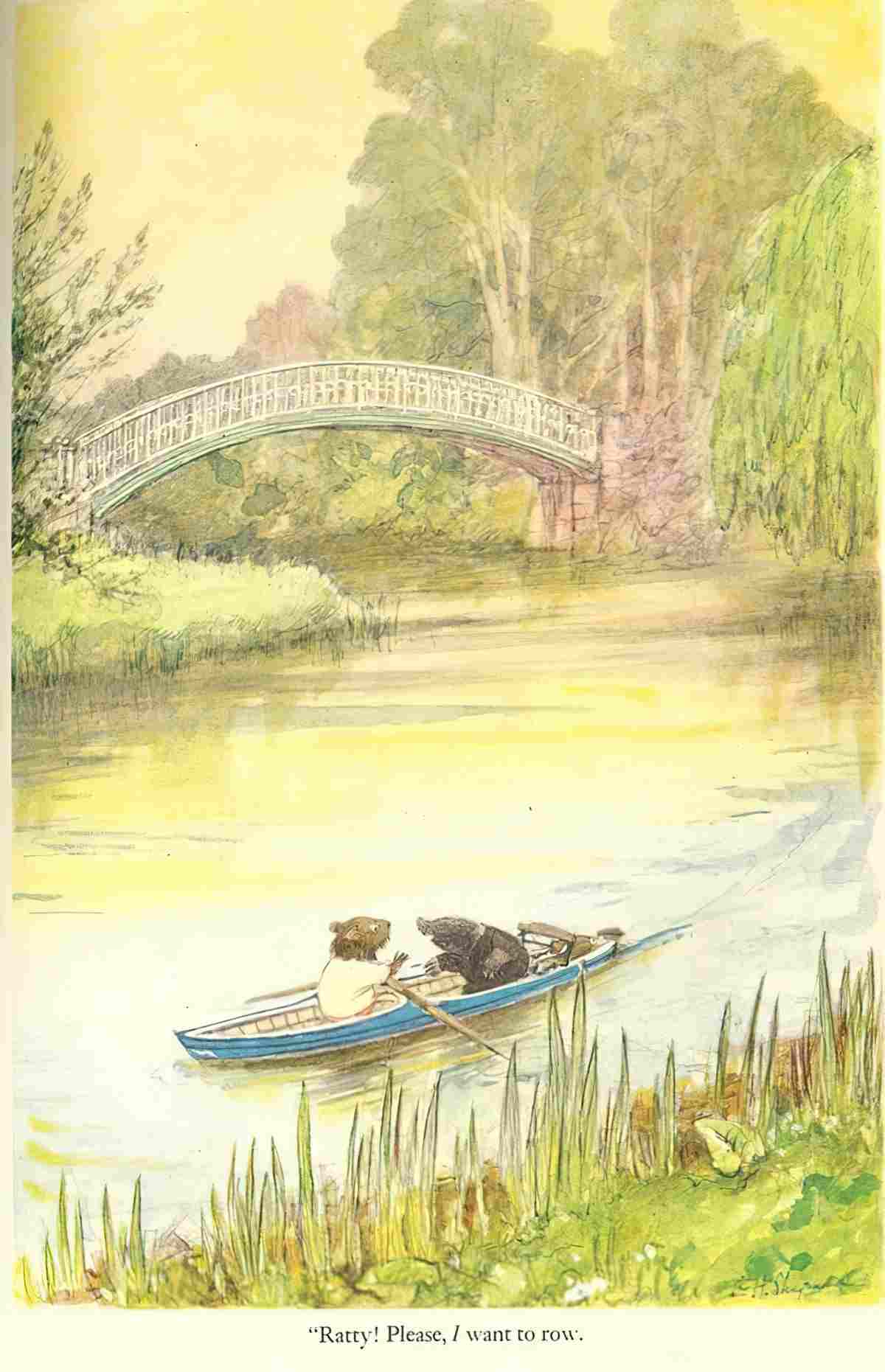

The most popular illustrator of The Wind In The Willows is often thought to be Ernest Shepard, who illustrated Grahame’s work for a 1931 publication. Shepard is THE Winnie the Pooh illustrator, so his style was familiar to mid-century children.

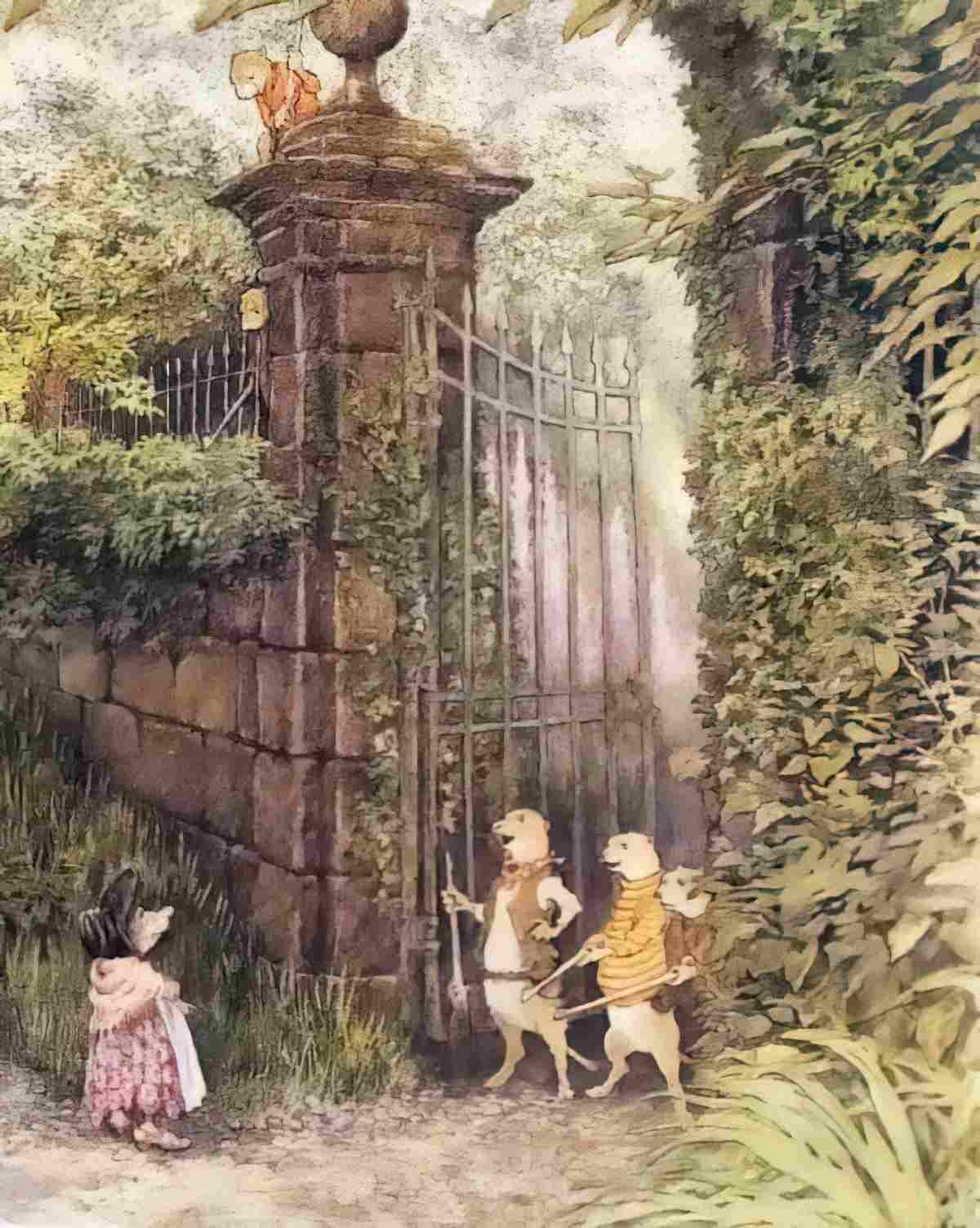

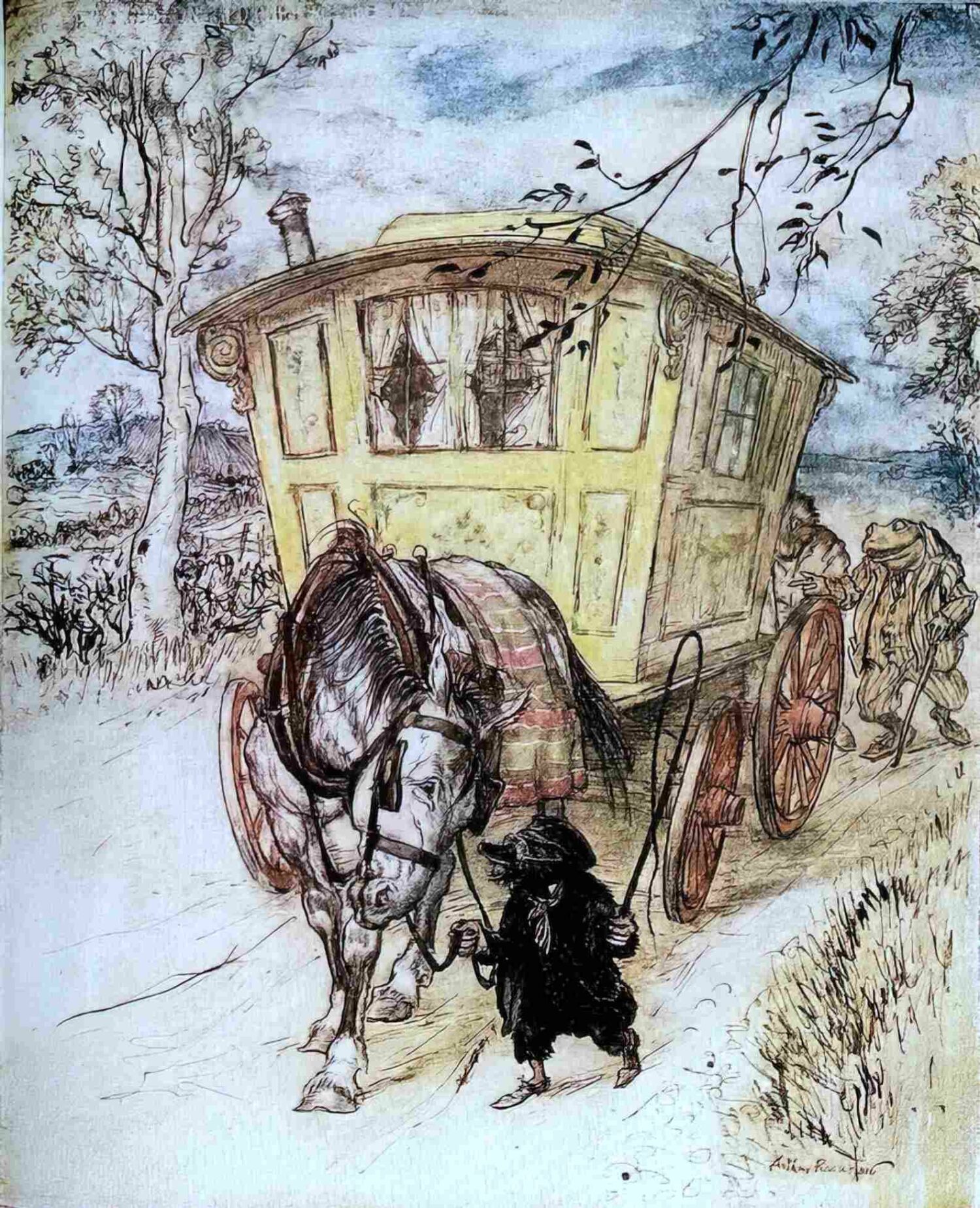

Arthur Rackham also illustrated The Wind In The Willows, for children reading cosy fiction during the second World War.

There are a number of excellent contemporary illustrators who have beautifully illustrated Kenneth Grahame’s classic.

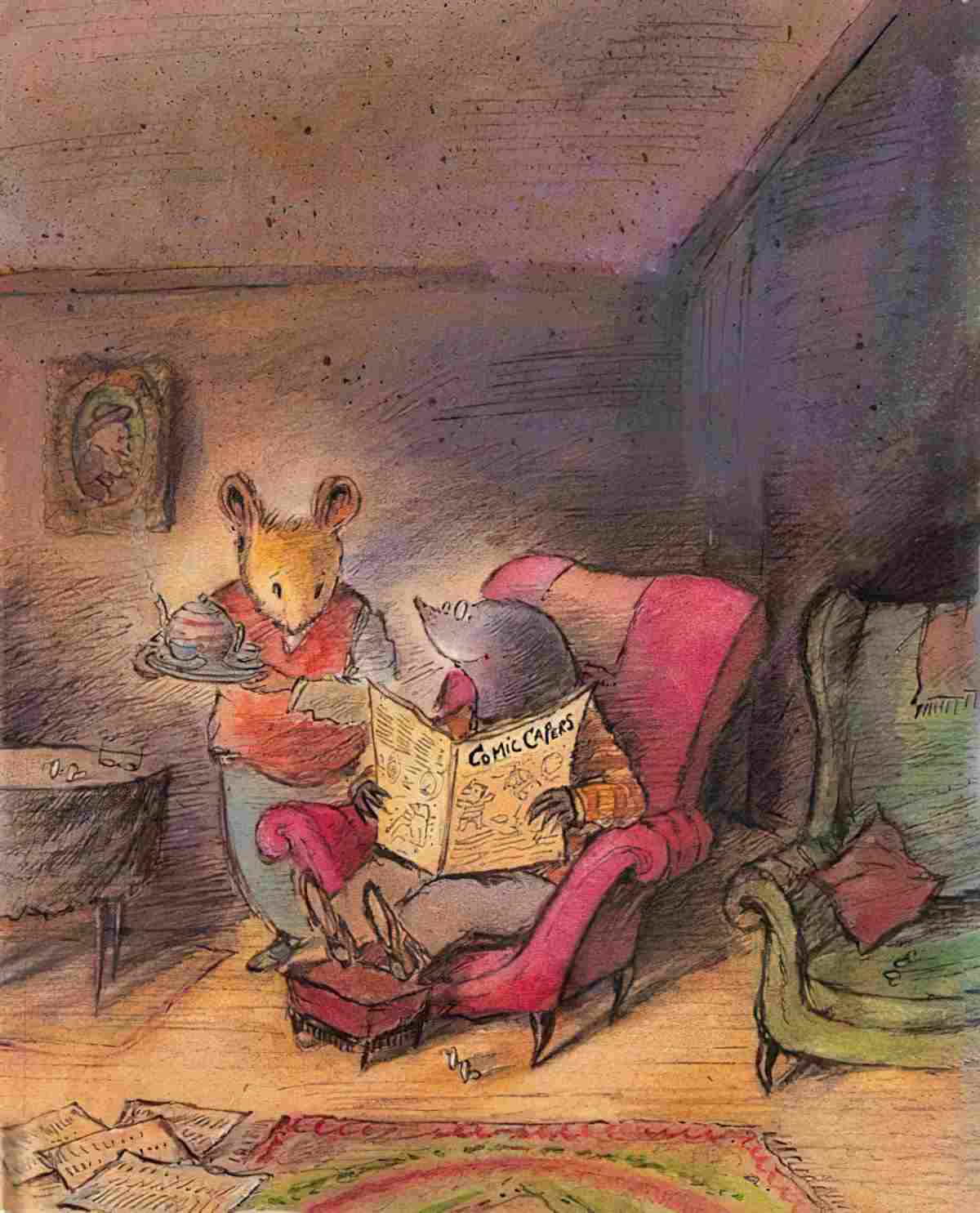

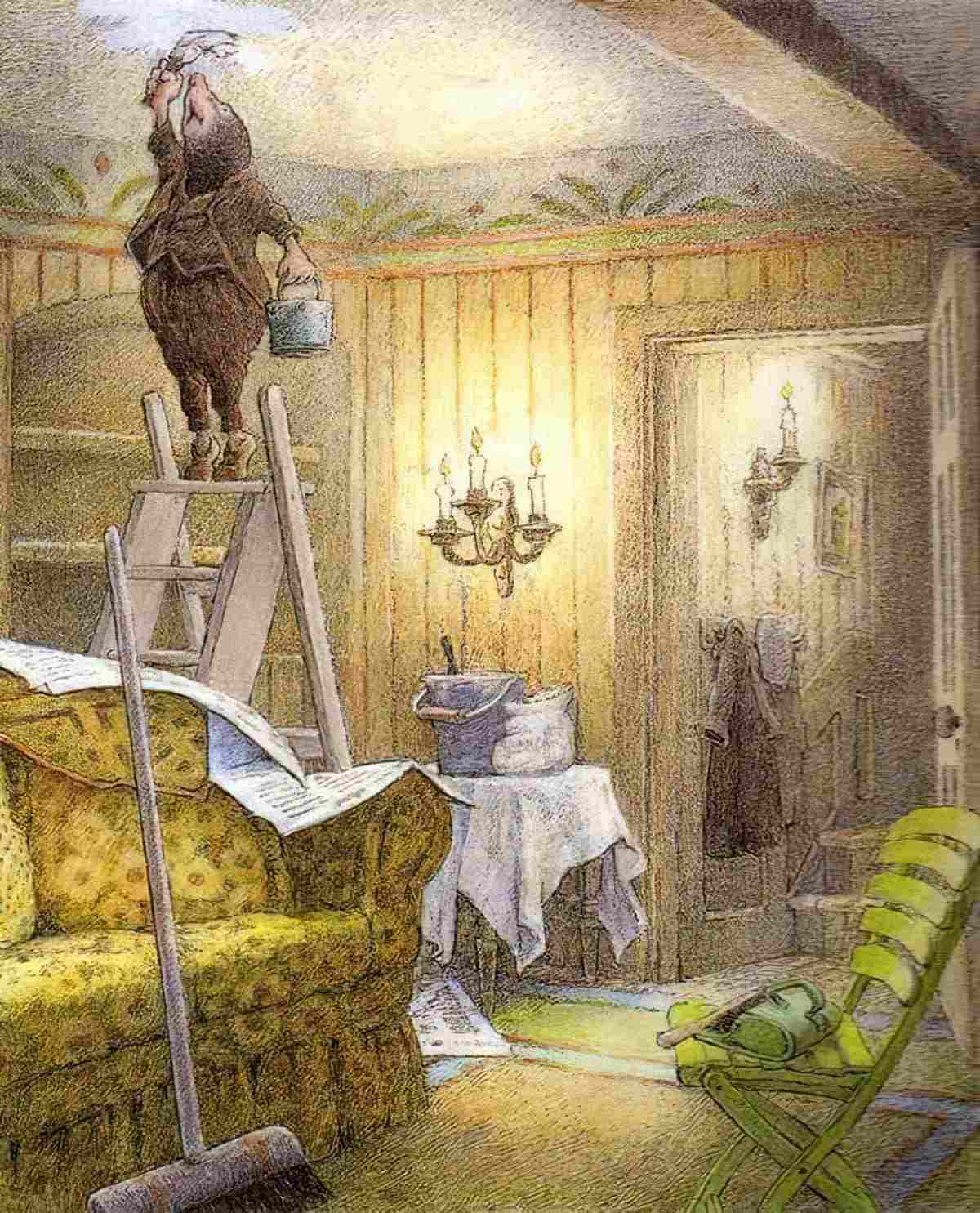

I love the warmth of the illustration below, and the pink of the chair really pops.

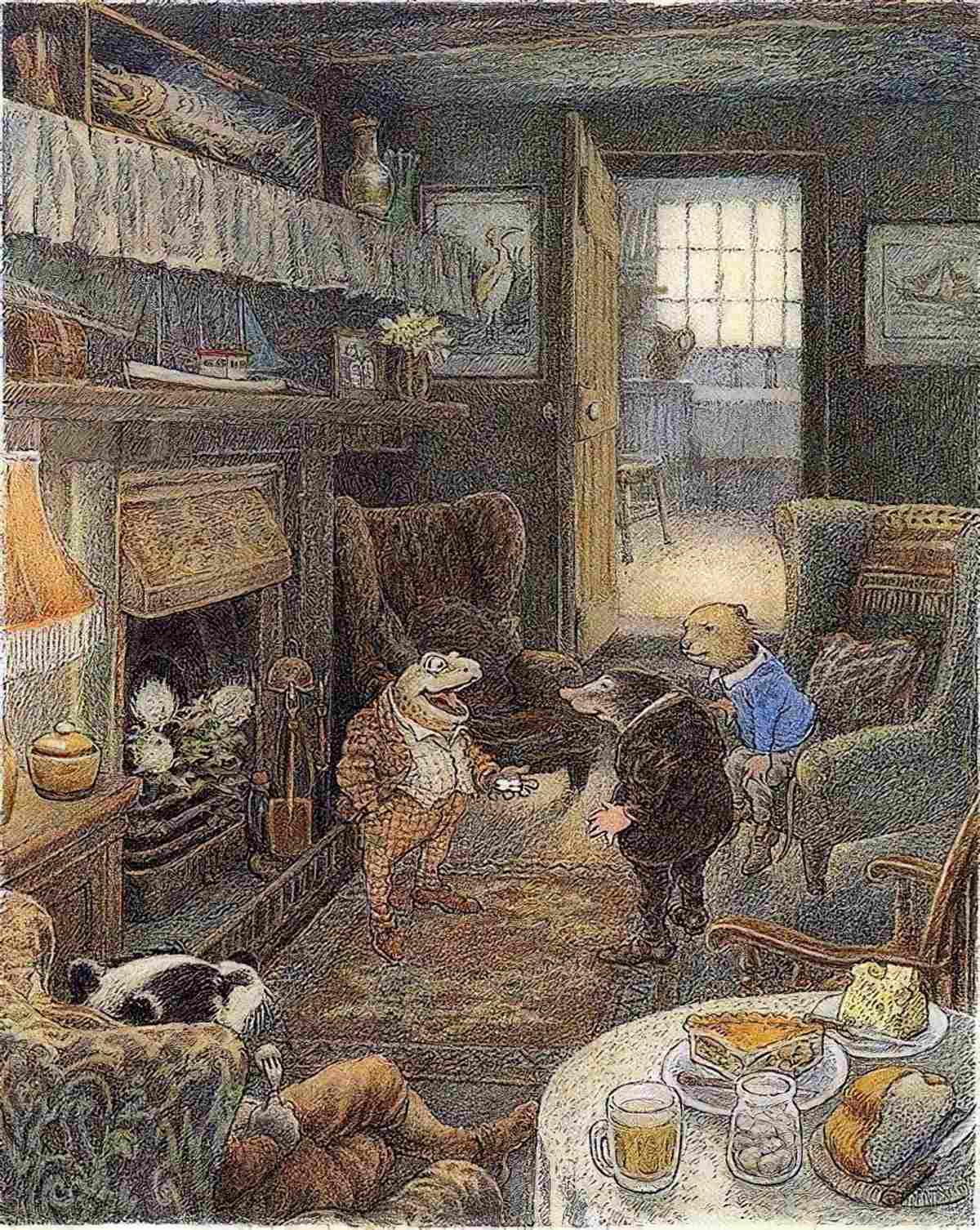

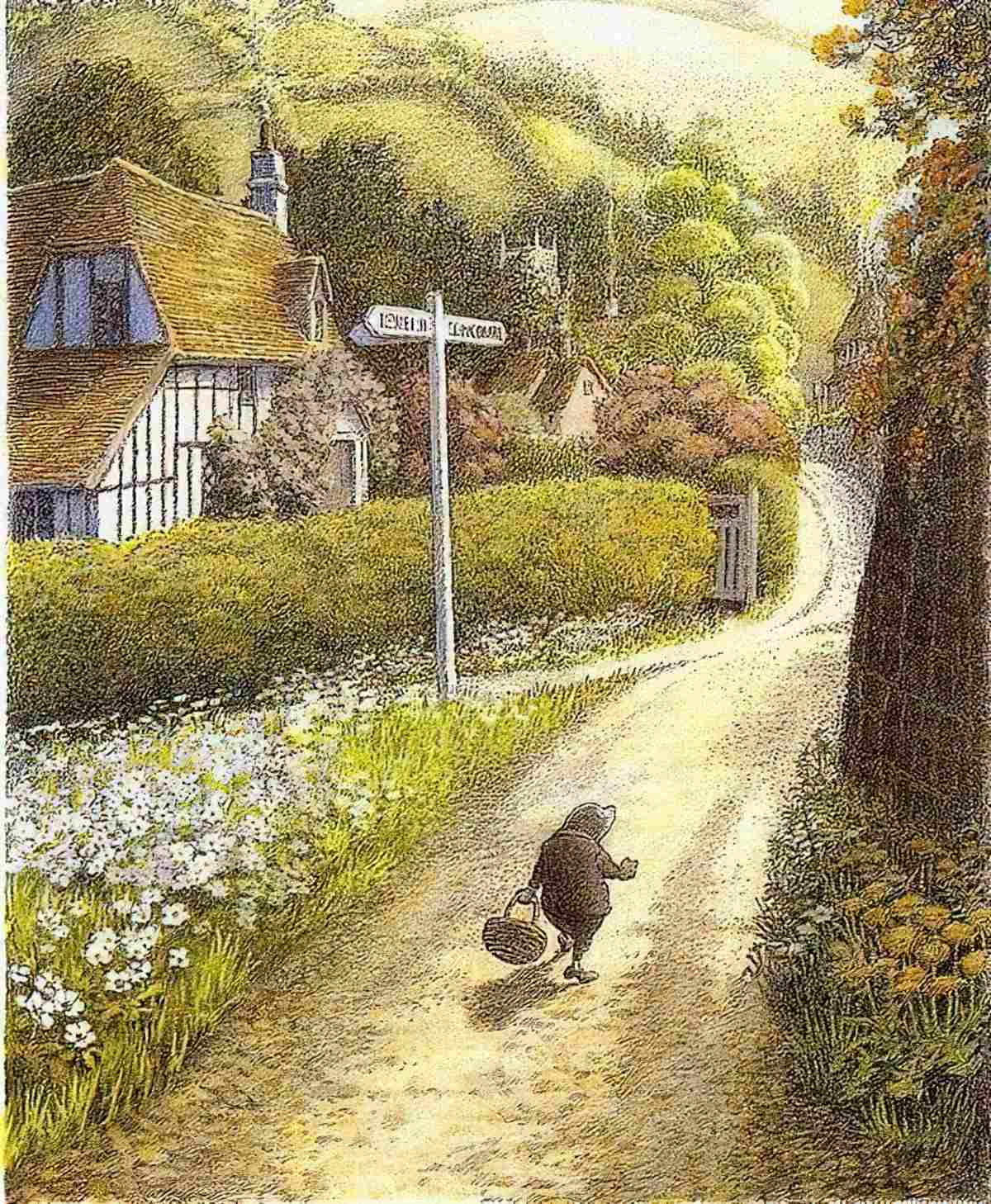

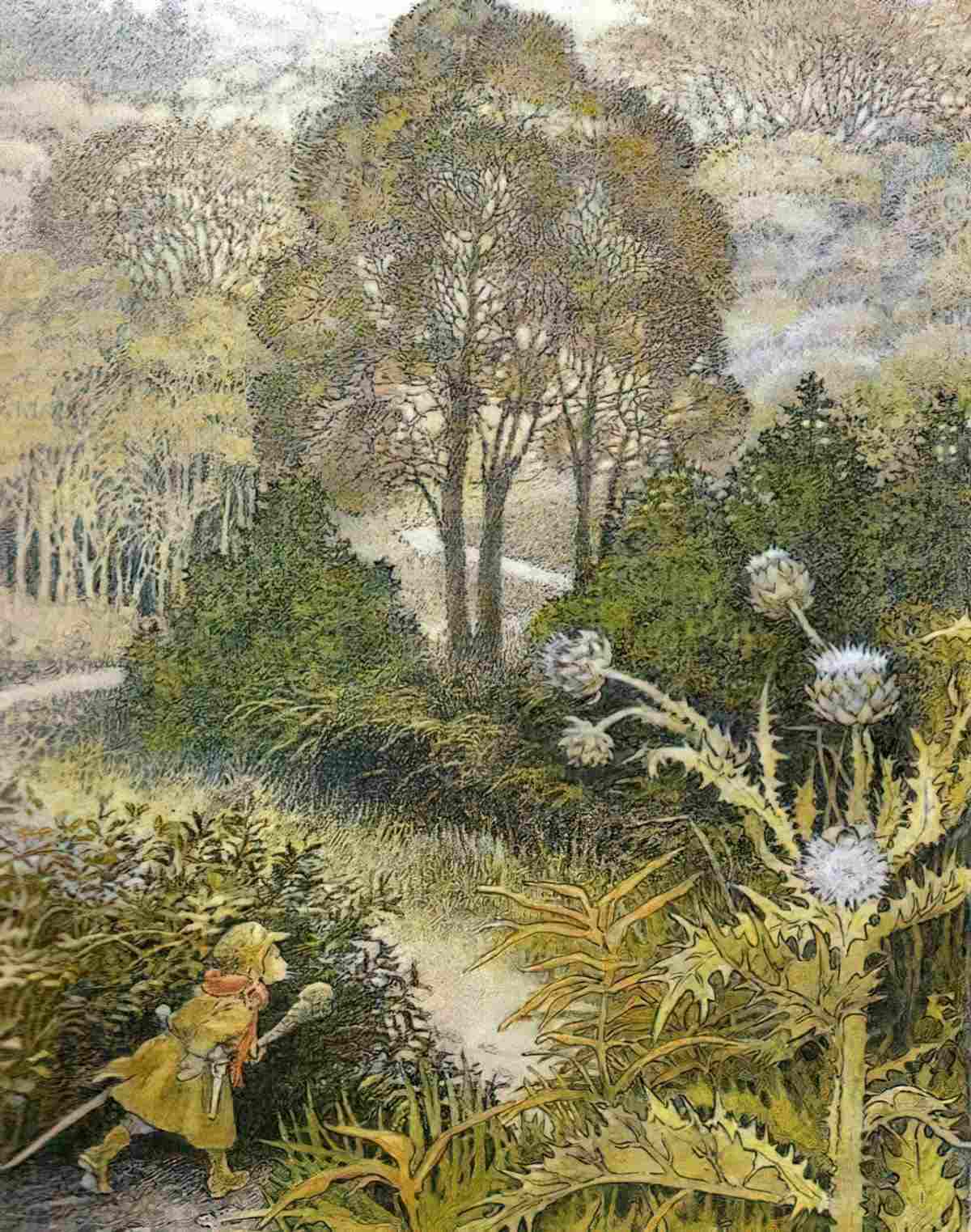

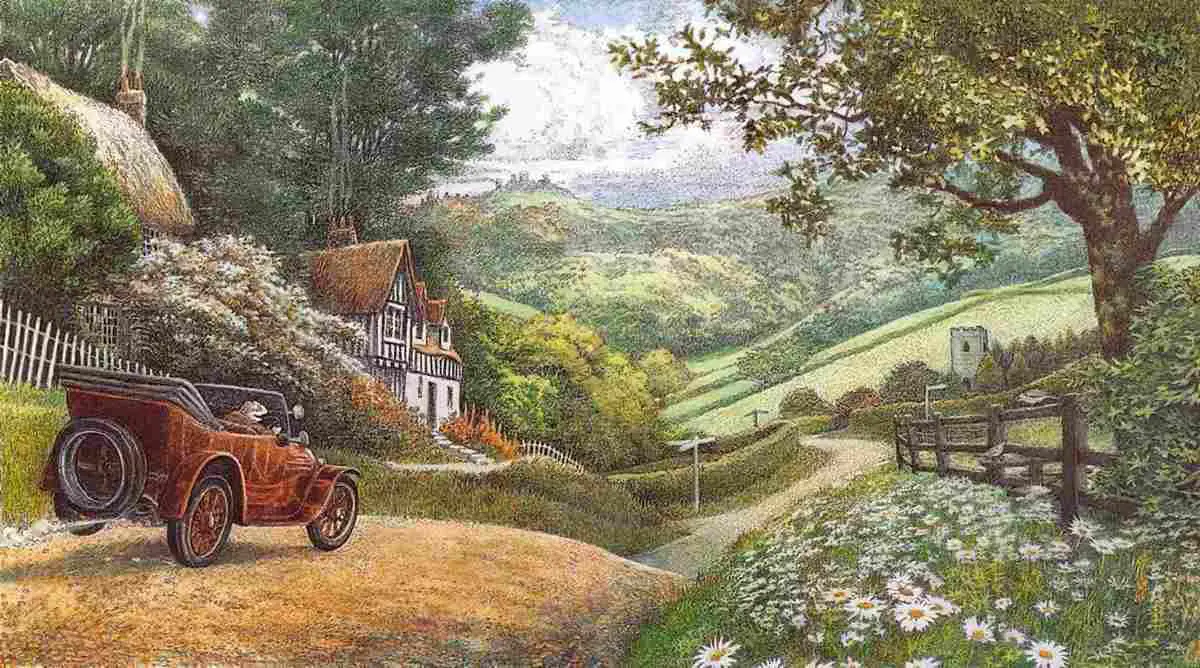

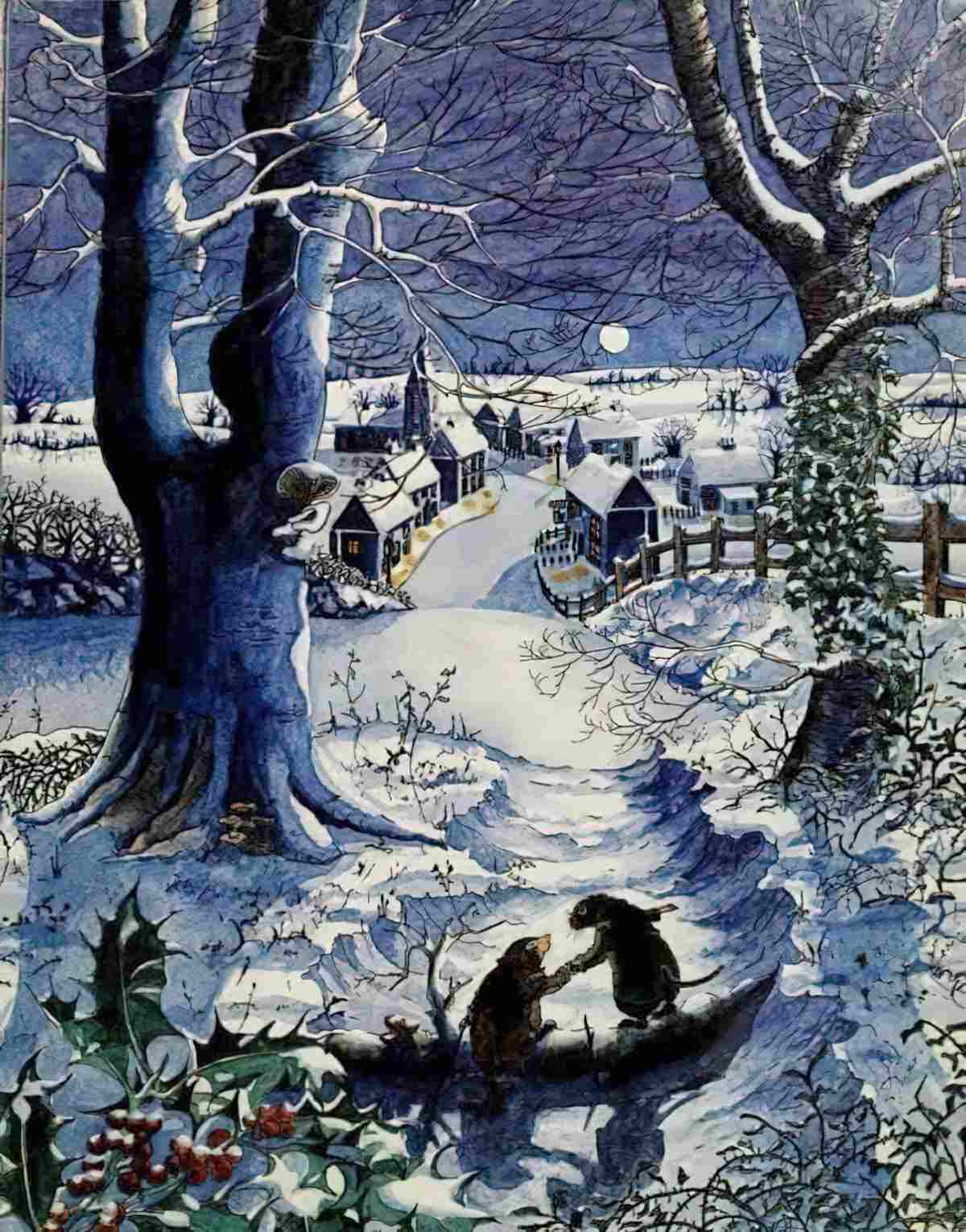

Inga Moore (born 1945) has an amazing knowledge of flora. (Moore also illustrated The Secret Garden and many other books.) I was surprised to learn that Inga Moore lives here in Australia, but everything made sense when I learned she was born in England. Moore is heavily influenced by her English heritage, which comes through in very (non-Australian) illustrations such as these:

I love the muted light of the British Isles — brilliant for artists and photographers alike. Australian light looks, and feels, vastly different.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

In a nutshell:

The Wind In The Willows has a slightly unusual two-part structure. The first half of the book is dedicated to the story of Mole (consistently referred to as ‘the’ Mole). Mole embarks upon a mythic journey and gets lost in the actual woods. In structure it’s not dissimilar from a fairytale like Hansel and Gretel. There’s a ‘storybook’ ending for Mole, who learns that he’s safest at home. But this storybook ‘ending’ happens less than halfway through the book, so we can deduce it’s not his real ending. The commentator below shares my view that this return to the cosy home is what makes this a children’s book, but I am about to argue that Mole enjoys a subtle (metaphorical) revelation:

Post-1945 British animal fantasies often start with a vision of the home, firmly ensconcing them in the realm of domestic fantasy. Like stories of toys that come to life, animal fantasy is, according to Peter Hunt, “rooted in a world recognizable to the child; like Winnie-the-Pooh it offers power and comfort simultaneously” (Introduction 185). No world is more recognizable to the child than the home, and British authors of this period recreate a very conservative, traditional ideal for the home. Precedence for this emphasis on home in animal fantasy goes back a considerable distance, but notably reached its apex in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908). Although Grahame’s story centers on bachelors rather than families, the idea of the essential nature of the home frequently takes center stage. All of the major characters’ homes are described in vivid detail. Leaving home (as in the Gipsy caravan adventure) and even contemplating leaving (Rat’s intention to go to sea) are given negative value. The final and pivotal episode in the book details the recapturing of Toad’s stately manor home, Toad Hall, from the Wild Wooders who have temporarily overrun it. Christopher Clausen suggests that, in The Wind in the Willows, “Although several of the characters are tempted by travel, home is clearly where the characters belong and where, after many vicissitudes, they return”. This, Clausen adds, makes Grahame’s novel a children’s book. Home has always been a centerpoint for British domestic fantasy, to help make the child reader comfortable in a world where strange things happened.

The Enemy Without: Post-1945 British Animal Fantasy and the Safety of Home Space, Karen Sands-O’Connor

Mole’s ‘real ending’ happens during a strange, drug-addled(?) chapter (famous only because it’s forgotten by almost everyone who reads it as a child) in which Mole experiences some kind of epiphany (okay, yes, a sexual awakening).

Now for part two. The story switches to that of Toad at Chapter 8. We’ve already met Toad, briefly, but his exploits remain largely secondhand.

Toad’s carnivalesque adventure of jail escape and crime is, like Mole’s, all about masking and unmasking. Toad’s journey can be considered the camp outworking of Mole’s quieter, inner journey towards becoming his authentic self.

Why the two distinct parts, with two distinct viewpoint characters, first Mole, then Toad? The Wind In The Willows is ultimately a single story: The mythic journey into the deepest part of one’s psyche, but it is played out in two very different character archetypes. The Mole’s self-revelation is subtle, so in case we didn’t pick up the symbolism, Toad’s adventure helps us out.

PARATEXT

There’s a well-known quote from The Wind In The Willows, which makes it into marketing copy:

There is nothing half so much worth doing as simply messing around in boats.

MARKETING COPY

The final chapter is titled “The Return of Ulysses”. Since he named his final chapter after the Odyssean myth, Kenneth Grahame was clearly very cognizant of the Odyssean part of his story’s structure.

The Wind in the Willows in fact utilises all three of the main types of mythic structure.

As categorised by Lucy Waddey:

1. The Odyssean pattern: Home is an anchor and a refuge, a place to return to after trials and adventures in the wild world. Home corresponds to Arcadia. This is the ‘here and back again’ pattern discussed below.

2. The Oedipal pattern: Found in domestic stories (Little Women, Little House etc.) These are stories where the child stays marooned in the home, but perhaps leaves imaginatively. This Oedipal pattern is also used in adult fiction when writing about women who, like children, are often confined to the home and can only escape in their imaginations. Katherine Mansfield’s female characters fit this pattern, with “How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped” as a stand-out example. (Also called the Robinsonnade mythic structure.)

3. The Promethean pattern: There is no home at the beginning of the story but the main character creates one as part of their maturation (The Secret Garden).

The Wind In The Willows is Odyssean when Mole goes into the woods and when Toad escapes from prison. It is Oedipal when the characters are enjoying their time at home, or on the river in Ratty’s case. It is Promethean because this is a story about found family — Mole starts out alone but finds his ‘people’. Ratty always loved his river, but comes close to leaving when he meets a charming old sailor rat. Toad, too, only turns Toad Hall into a ‘home’ after he has hit rock bottom, endured an intervention and ganged up with his new besties to fight the squatters.

I would like to rewrite a short synopsis for The Wind In The Willows, aimed an adult audience:

A man in the shape of a Mole’s body feels a yearning which can only be fulfilled by entering the most transgressive parts of his own psychology, externally represented by the Wild Wood. On his journey, he meets other men, each driven by their own secret (and not so secret) passions.

SHORTCOMING

Mole, by Kenneth Grahame’s hand, enjoys more generous treatment than a mole created by Hans Christian Andersen. Andersen’s mole in “Thumbelina” is in line with many storybook moles: He wears a velvet coat which gives him the appearance of gentility, but this is merely a mask. Andersen’s mole is irredeemable as a character (eventually revealed to be a Josef Fritzl type), rendered naturally detestable because he lives underground. Any creature who lives underground has difficulty shucking off our human associations with the Underworld — our imaginative underground Hell which goes back at least as far as the Ancient Greeks, who really fleshed it out. (As becomes more and more apparent, Grahame was familiar with classical mythology.)

When we first meet Mole, Kenneth Grahame shows him cleaning his house. Relatable. Also relatable: Getting jack of it, and wanting to go outside to enjoy the spring weather. Mole is redeemed in our eyes because he does not want to live under the earth; he is attracted to the ‘gravelled carriage-drive owned by animals whose residences are nearer to the sun and air’, and away from what Grahame’s unseen narrator describes as a ‘lowly little house with [a] spirit of discontent and longing’.

The mole in this particular story is, therefore, not your archetypal mole at all. Having subverted that in the opening paragraph, Mole of The Wind In The Willows is deftly written as empathetic. (In reality moles prefer to live under the earth, for which they are perfectly evolved.)

Mole’s main shortcoming is his naivety. Having been safely ensconsed under the ground until now, he knows nothing of the wider world and is now at its mercy. In this respect, Mole is a classic children’s book character. Children, likewise, start off know nothing of the wider world.

DESIRE

What makes Mole leave his home in the first place? Mole is answering the classic Call to Adventure. ‘Something up above was calling him imperiously’. Mole is your classic young man from fairytale. He leaves home because of some deep, ineffable and urgent need. He is so driven to leave home that it feels as if a voice is calling from above.

Under the surface, underpinning his expedition, Mole wants to find love and companionship. (He becomes Ratty’s ‘particular friend’, to quote the Otter.)

OPPONENTS AND ALLIES

The Elderly Rabbit — Wants Mole to pay a toll for using a private road. This rabbit is surrounded by many others. Mole isn’t cowed by them and for some reason thinks ‘Onion-sauce! Onion-sauce!’ is a good roast. Mole is now more relatable because he has courage.

Ratty — introduced as “the Water Rat!” which tells us Mole already knows this guy a little. Ratty invites Mole to the other side of the river.

Toad — Grahame uses the storyteller’s trick of introducing the idea of Toad in conversation before putting Toad in a scene. This increases audience curiosity:

“It’s never the wrong time to call on Toad. Early or late he’s always the same fellow. Always good-tempered, always glad to see you, always sorry when you go!”

The Wind In The Willows

“He must be a very nice animal,” observed the Mole.

The compliments continue, which will serve as ironic juxtaposition when we all meet Toad and realise he is a heavily flawed individual. Irony is left up to the reader to notice. After Rat and Mole do the work of clearing up after Toad and providing the necessaries, Toad remarks ‘what a pleasant easy lift it was they were all leading now’.

When the threesome go for a ride in Toad’s canary coloured cart, it is soon revealed that Toad has a significant shortcoming: He is easily overcome by the adrenaline of driving, which puts him into a kind of trancelike state. Though Toad is about to get himself a motorcar himself when someone zooms past hooting, expecting pedestrians to jump out of the way. This scene is probably how the general populace felt about the rich people who were first able to afford cars. Already enjoying buckets of privilege, I can’t imagine the first drivers were considerate. There were very few cars on the road. Road rules took some time to develop. I’m guessing it was regularly up to pedestrians to jump out of the way of oncoming vehicles, and that Kenneth Grahame is commenting on the perceived mental state of such drivers, and also the mental state of people rich enough to buy one, seeing them for the first time. “I must have me some of that.”

When news reaches Mole and Ratty that Toad has ordered himself ‘a large and very expensive motor-car’ we know trouble is coming.

Badger — If Grahame utilised the trick of ‘describe then introduce’ for Toad, he uses it in a big way for the mysterious Badger. All the time he’s ensconsed himself at Ratty’s, Mole is hoping to meet this Badger.

THE HEAD HEART GUT POLARISATION OF THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS CHARACTER ENSEMBLE

At his website Cockeyed Caravan a.k.a. Secrets of Story, Matt Bird talks about how ensembles of fictional characters are often distinguished by certain exaggerated characteristics, commonly with trios, each representing the head, heart and the gut. He summarises this theory on this podcast. I believe it works for the main trio in The Wind In The Willows:

Head — Ratty is the most sensible of the three, though he’s not your classic Hermione/Lisa Simpson character. He is very good at packing picnics, and is quite analytical about what comprises a decent spread. He is the character who organises Toad’s care after Toad goes into a stupor after seeing his first motor-car. The head character is easy to spot: This is the character who comes up with all the plans. When Ratty discovers Badger’s door, Mole waxes lyrical: “Well, I’ve read about that sort of thing in books, but I’ve never come across it before in real life. You ought to go where you’ll be properly appreciated. You’re simply wasted here, among us fellows. If I only had your head, Ratty—”

Heart — This is Mole. Mole is led by his heart throughout this entire story, even to the point where he will go deep into the dangerous Wild Wood due to some deep yearning. He falls quickly and easily in love (I deduce). Mole also has aspects of ‘gut’ because of his love of food/sex. Mole is the most rounded of the main characters in this book; the ‘main character’ often embodies all of the different aspects of polarisation precisely because they are rounded.

Gut — Toad is your classic Gut character: childlike, egotistical and driven by his own strong and selfish desires. He sees a motor-car and immediately wants it, which is similar to Mo Willem’s pigeon, who has got it into his head that he wants a puppy. Some commentators (Seth Lerer and Annie Gauger) have suggested that Toad is the fictional representation of real-life Oscar Wilde, who also found himself humiliatingly imprisoned. “He’s convinced he’s a heaven-born driver, and nobody can teach him anything; and all the rest follows.” He is described as The Terror of the Highway, Toad The teror, the traffic-queller, the Lord of the lone trail. Toad transformins from an ordinary fellow led by his gut into a dangerous alter ego as soon as he dons the clothing of a driver, or hears the engine of a motor-car. Comedy derives from characters thinking they are one thing but are actually another. Commonly, the gut character thinks they are the head. Toad escapes forced intervention from his three closest comrades by tying a rope out of sheets and leaving by the window. Walking along the road of escape, he marvels at how much smarter he is than Ratty (the genuine head character):

‘Smart piece of work that!’ he remarked to himself chuckling. ‘Brain against brute force — and brain came out on the top — as it’s bound to do. Poor old Ratty! My! won’t he catch it when the Badger gets back! A Worthy fellow, Ratty, with many good qualities, but very little intelligence and absolutely no education. I must take him in hand some day, and see if I can make something of him.’

The Wind In The Willows, “Mr Toad”

Other gut characters who comically believe they are the head: Erlich Bachmann from Silicon Valley and Grizz from We Bare Bears.

Aside from these basic three exaggerations of character, an expanded cast includes even more polarisation:

Spirit — This character is above being driven by particular base desires, and is not susceptible to needs at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy (misappropriated from Native Americans). This character in The Wind In The Willows would be Badger. His eminence is emphasised by the fact that the reader doesn’t get to meet him right away. He starts out as a mystical presence. ‘He looked kindly down on them and patted both their heads.’ (Badger is literally bigger than Mole and Ratty.) He speaks ‘paternally’. Getting back to Jung, the Spirit character is the Wise Old Man, or anima. (Jung was all about gender binaries: anima is ‘the female principle within the man’. It needs updating, but I can see how Badger is both patriarchal and nurturing, so I’m rolling with it for now.)

Some fictional ensembles include a ‘Spleen’ character (throwing negativity about them everywhere they go) and also a ‘Groin’ (cocky) character, interested in sex. In children’s stories, or quasi- children’s stories such as this one, written in the Edwardian era when writing openly about sex was difficult, at best, food equals sex. (This remains the case in children’s literature.)

For all their differences, I notice significant similarities between Mole and Toad. Considering how rare this is, in fiction and in real life, both Mole and Toad are quick to admit they are wrong, and the heap immediate praise upon those who were right.

There are a number of other opponents met along the way (mostly by Toad). At the end there’s a gang of squatter weasels and stoat sentries.

PLAN

Mole has left home because he’s bored (with housework) then decides he’s on a holiday. This isn’t so clear in the book, and a 1988 Australian (Burbank) adaptation of The Wind In The Willows changes the opening scene to include dialogue which emphasises how very bored Mole is. The screenwriters must have seen that there’s a bit of a problem when engaging a contemporary (1980s) child audience, who may not find it satisfying or believable that an a character simply leaves home for ages with no obvious mission driving the expedition.

Wind In The Willows (Burbank Version) on YouTube

When Mole runs into Ratty he moves in with him, seemingly for good. He must have fallen in love with Ratty but we have to make do with cryptic sentences such as ‘every day brought its amusements’. That said, the description of the river, via Mole’s experience of it, suggests a creature in the throes of limerance. The language of love rivals D.H. Lawrence:

The pageant of the river bank had marched steadily along, unfolding itself in scene-pictures that succeeded each other in stately procession. Purple loosestrife arrived early, shaking luxuriant tangled locks along the edge of the mirror whence its own face laughed back at it. Willow-herb, tender and wistful, like a pink sunset cloud was not slow to follow. Comfrey, the purple hand-in-hand with the white, crept forth to take its place in the line; and at last one morning the diffident and delaying dog-rose stepped delicately on the stage, and one knew, as if string-music had announced it in stately chords that strayed into a gavotte, that June at last was here.

Kenneth Grahame’s loving description of a river

My Year 12 English teacher introduced us to D.H. Lawrence and our class spent a quarter of one formative year analysing sex metaphors. It changed me forever.

“It seethes and seethes, a river of darkness, putting forth lilies and snakes”

D.H. Lawrence’s river metaphor from Women in Love

Naturally, I can’t read Kenneth’s Grahame’s description of that river or of the Wild Wood without a D.H. Lawrence spin.

So anyhow, now that Mole’s association with Ratty has partially revealed something about himself about his own desires, the possibilities probably feel endless. While comfortable with Ratty, Mole simultaneously develops this strange attraction to the mysterious Mr Badger, who is much bigger than the both of them. It seems to me that Mole is attracted to bigness (or power). The wish to be protected and enveloped by something or someone much bigger and stronger than oneself is not an unusual fantasy. To take just one example from folklore, consider the Islamic concept of the Djinn (genies, but not in the Aladdin sense). Some varieties of Djinn are believed to interact with humans (ghouls, marid and the ifrit.) The ifrit are giant and powerful Djinn. While they are thought to mostly marry each other, the giant ifrit Djinn sometimes marry humans. I think this sort of mythology speaks to a deep human desire which endures in many adults to feel safe and protected by something much larger than ourselves. These giant creatures are sometimes sexualised in mythology.

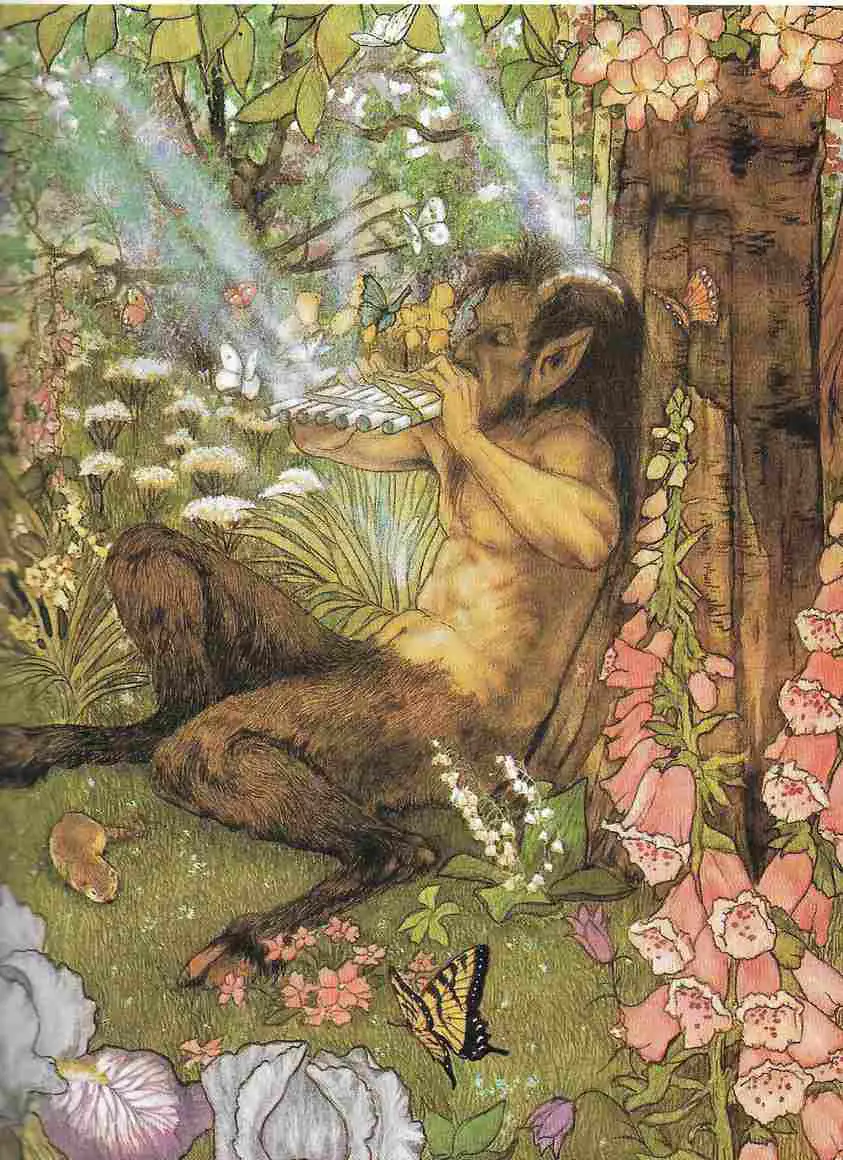

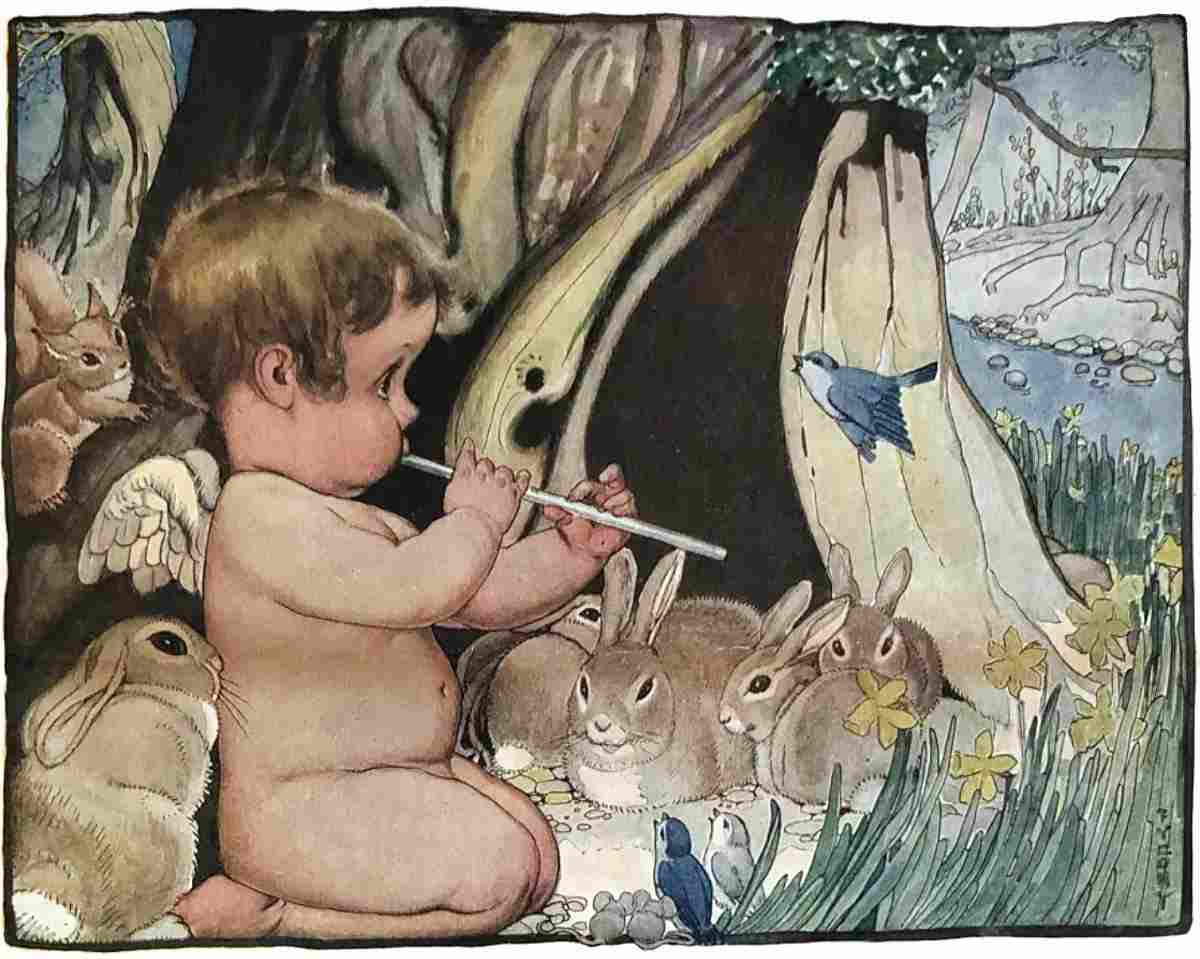

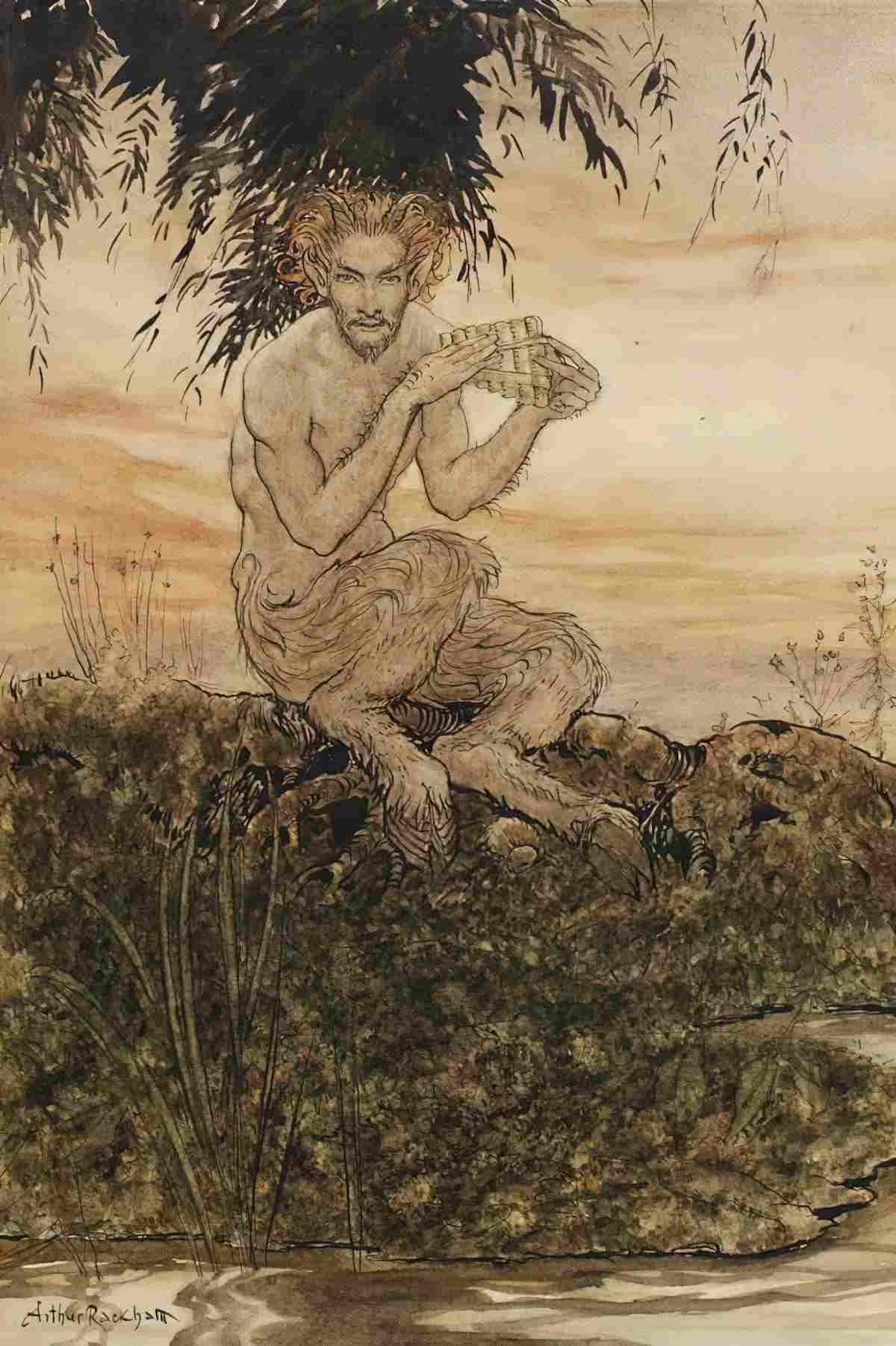

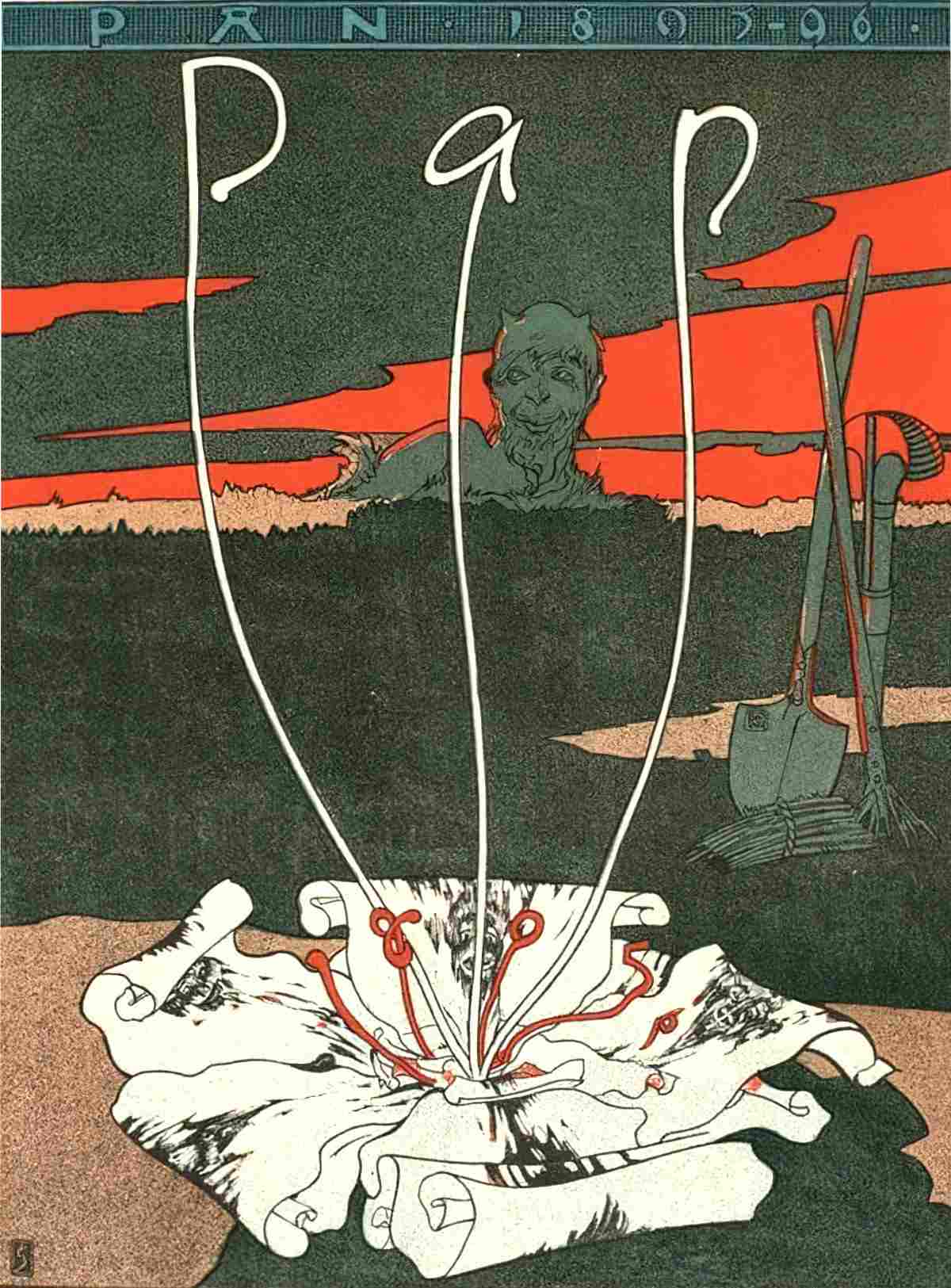

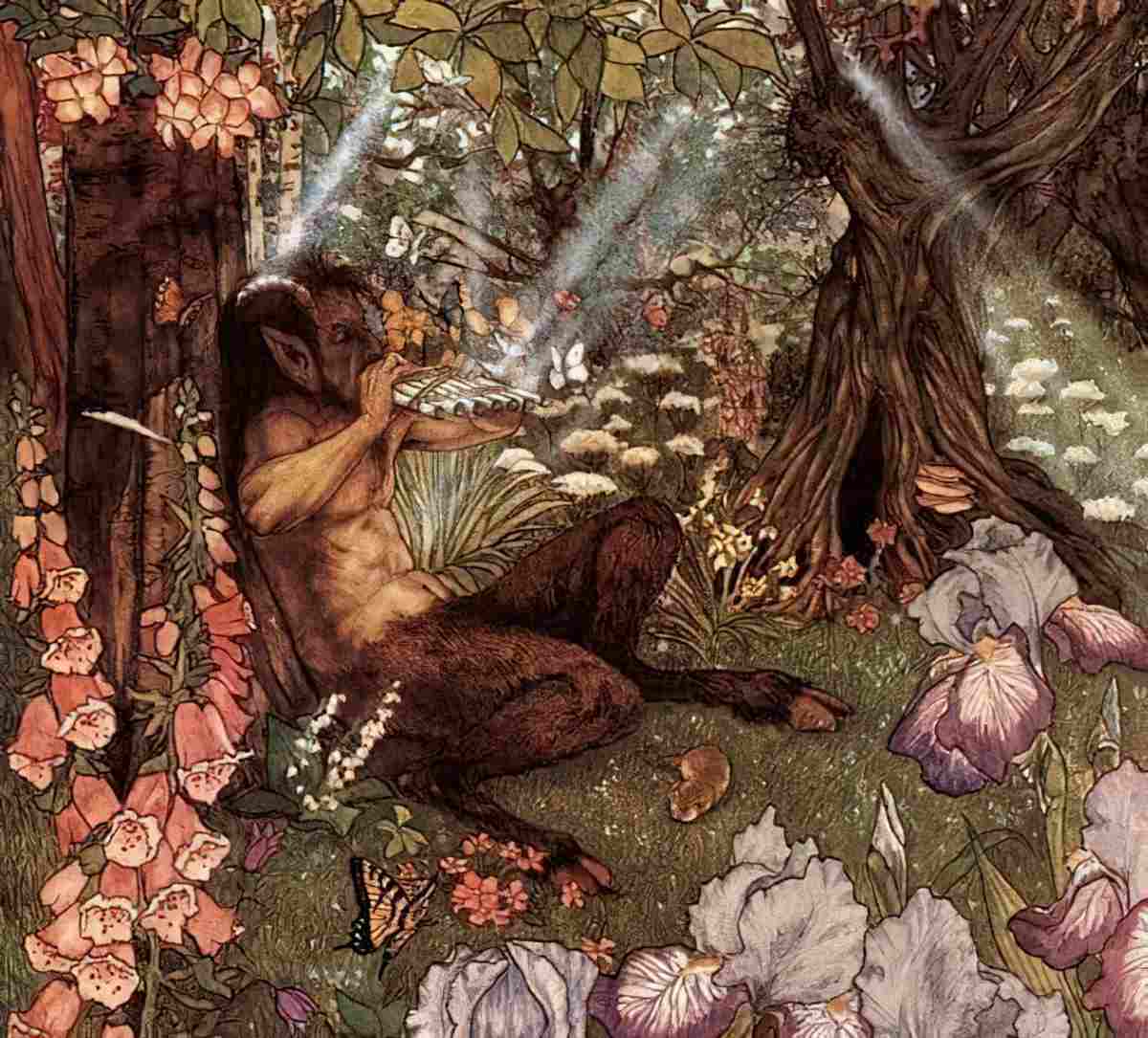

Anyway, this theory explains the appeal of demigod of nature, Pan, who appears to Mole and Ratty (at least in illustrations) as this very large, beautifully muscled figure, who could squish the pair of them in one careless swipe of the hand if he wanted to.

J.M. Barrie was also interested in Pan the Greek god:

Peter Pan is among other things an incarnation of the Greek demigod Pan, who figures so often in late Victorian and Edwardian literature. There, as in classical tradition, he was a split of the woods who embodied natural energy and sexual passion and was represented as a man with goat’s legs and pointed ears, playing on a reed pipe. Barrie’s Pan, however, is a child who plays pies and rides a goat. […] Though Peter is less powerful than the Greek god Pan, he is not without his dark side.

Alison Lurie

Although Mole could be perfectly happy with Ratty, he has this other side of himself to explore. So that’s why Mole sets out from Ratty’s in search of Mysterious Mr Badger. This is not on the page. Not in a book which is ostensibly written for children.

Take a close look at the figurative language. When Mole enters Nature, the Wild Wood seems to be ‘exposing secrets’. It is ‘bare’ and has ‘kicked off its clothes’. Transferred epithets galore. (I learned that phrase in the D.H. Lawrence term of Year 12.) The former leafy woods are described as a ‘masquerade’. This masquerade masks what, exactly?

Note that the unseen narrator has been making references to masking all along:

Most of the low latticed windows were innocent of blinds, and to the lookers-in from outside, the inmates, gathered round the tea-table, absorbed in handiwork, or talking with laughter and gesture, had each that happy grace which is the last thing the skilled actor shall capture — the natural grace which goes with perfect unconsciousness of observations.

The Wind In The Willows, “Dulce Domum”

Then there’s the mask of civility which the narrator explains for us, creating a humorous ironic distance between how the characters behave in polite company, sparing the feelings of others, and how they really feel. In the passage below, Mole has just apologised to Ratty for his humble abode, but his true feelings of his home, which he loves, become gradually less concealed:

Then, while the rat busied himself fetching plates, and knives and forks, and mustard which he mixed in an egg-cup, the Mole, his bosom still heaving with the stress of his recent emotion, related — somewhat shyly at first, but with more freedom as he warmed to his subject — how this was planned, and how that was thought out, and how this was got through a windfall from an aunt, and that was a wonderful find and a bargain, and this other thing was bought out of laborious savings and a certain amount of ‘going without’. His spriits finally quite restored, he must needs go and caress his possessions, and take a lamp and show off their points to his visitor and expatiate on them, quite forgetful of the supper they both so much needed; Rat, who was desperately hungry but strove to conceal it, nodding seriously, examining with a puckered brow, and saying, ‘wonderful’, and ‘most remarkable’, at intervals, when the chance for an observation was given him.

The Wind In The Willows, “Dulce Domum”

Of all the trees that exist in the world, the willow feels most like a hidden room, with its drooping branches. The willow tree conceals, except, of course, when the wind blows. This explains the metaphorical significance of the title. (Pair with the fact that this story is full of masking motifs.)

In midmost of the stream, embraced in the weir’d shimmering arm-spread, a small island lay anchored, fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder. Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

The Wind In The Willows, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”

(When electric lighting was first making its way into homes, people worried that it would be unsafe for women and children, for the reason that peeping Toms could peer in, undetected.)

Kenneth Grahame’s mask in The Wind In The Willows is the mask of the true self (isn’t it always?), which manifests only after a near death experience plunging Mole into the deepest, darkest part of the woods, no, sorry, of himself. Mole is plunged into the deepest most repressed parts of himself.

Mole feels the Wild Wood is full of faces, watching him. This is his self-consciousness pushing up against a base instinct. He is trying to get in touch with by entering the woods (hoping to meet The Badger).

If only he could get away from the holes in the banks, he thought, there would be no more faces. He swung off the path and plunged into the untrodden places of the wood.

The Wind In The Willows

(There’s a reason why Michel Foucault was deeply interested in surveillance; to lead a transgressive life in a bigoted society is to feel constantly under surveillance oneself.)

Anyhow. That, folks, is why Mole gets himself lost in the Wild Wood for absolutely no good reason. His base desires override his intellectual fear of the place and he is drawn into it despite himself. Watch TV adaptations for children and this desire isn’t obvious in any of them. I’ve watched the 1983 claymation and also the 1995 animation (book ended with live action) and both times wondered why, exactly, Mole sets off into the Wild Wood despite having been told it’s dangerous in there. (Well, Ratty is a bit ho-hum, I guess. “It has its good sides and downsides…”)

Only via a metaphorical reading do I understand that Mole is enchanted by this wood (and by the enigmatic fantasy of Badger) in the same way Toad is completely possessed by the thrill of driving motor-cars. Similarly, Ratty is enamored by his beloved boats on a beautiful river which swells and quietens according to season. Ergo, we are each of us driven by some deep desire. We must find out what drives us as a way towards understanding ourselves. Only then can we be truly happy in our own skins (in our own homes).

All this to say, Mole hasn’t made plans, as such. This is a melodrama. He’s propelled along by circumstances. If anything, it’s Mole’s Id driving the action. (Cf. Freud, who I don’t like to dwell on.)

After the conclusion of the Wild Wood near death experience and Mole’s return home, Badger drives a new plan: The three of them will stage an intervention on the dangerous driver, Toad, who has had any number of altercations with police. The three visit Toad and strip him of his driving clothes. Badger says to Toad:

“You will come with me into the smoking-room, and there you will hear some facts about yourself; and we’ll see whether youc ome out of that room the same Toad that you want in.”

The Wind In The Willows

This chapter serves partly to shift the focus to Toad, who is the viewpoint character from here on in. (After the horny chapter, that is.)

Toad is lolling about melodramatically in a dungeon, and it’s not actually Toad who comes up with the plan for his escape. That would be the girl who suggests he dress up in the washerwoman’s clothing, since Toad looks very much like her.

After pulling this off, Toad’s brain kicks into gear and he is required to make and modify his escape plan a number of times as the police are on his tail. This involves preying on people’s sympathies, promising washing in return for a ride on a train and so on.

The “Wayfarer’s All” is another horny chapter which takes the viewpoint away from Toad, temporarily. Ratty feels horny and goes cruising, meets a hot navy guy elder in a faded blue jersey.

‘That reminds me,’ said the polite Water Rat; ‘you happened to mention that you were hungry, and I ought to have spoken earlier. Of course, you will stop and take your midday meal with me? My hole is close by; it is some time past noon, and you are very welcome to whatever there is.’

The Wind In The Willows, “Wayfarers All”

They then have a ‘what do you like?’ conversation, as advocated by sex positive therapists. It’s really quite lovely. (You can’t not read it like this, right?) However, because it’s a ‘children’s book’, we get a description of a picnic. During this chapter, Ratty gets his own character arc a.k.a. sexual awakening.

‘And you, you wil come too, young brother; for the days pass, and never return, and the South still waits for you. Take the Adventure, heed the call, now ere the irrevocable moment passes! ‘Tis but a banging of the door beehind you, a blithesome step forward, and you are out of the old life and into the new! Then some day, some day long hence, jog home here if you will, when the cup has been drained and the play has been played, and sit down by your quiet river with a store of goodly memories for company. You can easily overtake me on the road, for you are young, and I am ageing and go softly. I will linger, and look back; and at last I will surely see you coming, eager and light-hearted, with all the South in your face!’

The Wind In The Willows, “Wayfarers All”

You only get one life. Live it! Be young, have fun! Go ‘South’ if you want to! Make lots of nice memories so that when you’re old you’ll have plenty to remember.

In the battle scene of this chapter, Ratty goes home and tells Mole he’s leaving. Mole ‘grapples him strongly’ and ‘drags him inside, throws him down, holds him’. After this, they are forced to negotiate the terms of their relationship. Mole suggests Ratty write poetry, though Ratty ‘sucks a great deal more than he scribbled’. (The end of the pencil, of course.)

Back to Toad, who is still dressed down as a washerwoman and stuck in the wild, trying to find his way back to aristocracy. He is such an irrepressible show off that when he meets a similar woman to the washerwoman he’s trying to pass himself off as, he soon reveals his ineptitude; the trickster is tricked.

Then he steals a horse, meets a ‘gipsy‘ who wants to buy it for ‘a shilling a leg’, then, in the sort of coincidence that works will in comedy, the very same people from whom Toad stole the car in the first place notice a poor old washerwoman slumped in a heap on the side of the road and offer to give her a lift.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Because this is a mythic story, the plot includes many brushes with death, escalating in intensity.

The first is minor incident: Ratty takes a tumble in his own boat. He comedically picks himself up and keeps talking, as if it never happened.

Next, Toad’s canary coloured cart is overturned when a motor-car startles his horse.

Then Mole finds himself alone and lost when he goes in search of the elusive, attractive Mr Badger in the Wild Wood. Ratty comes to his rescue. A romantic wish fulfilment fantasy: To be rescued from death by someone you love. Ratty informs Mole that you don’t come into the woods by yourself. You come in couples, at least. Ratty explains that there are ‘passwords, and signs, and sayings which have power and effect’. Polari. On the way out they fell into several holes and get wet through, and so on. There is no way out. Like Hansel and Gretel, they are lost, lost, lost.

Ratty’s spiritual journey happens in the “Wayfarers All” chapter, culminating in the erotically charged physical tousle with Mole, who doesn’t want him to take off with the old sailor.

As for Toad, his mania for cars overcomes him when he’s propped in the back seat of a ‘terrible motor-car’. He struggles with himself to suppress his desires to drive it, and loses.

‘It is fate!’ he said to himself. ‘Why strive? why struggle?’ and he turned to the driver at his side.

The Wind In The Willows, “The Further Adventures of Toad”

This could be said of all the internal battles of this story, whether they’re Moles or Ratty’s.

There is a final big battle at the end, which bands all of the main characters together, united against the weasels who are squatting at Toad Hall.

ANAGNORISIS

This is the part where any masks come off, where the characters learn something about themselves, and the audience learns something about life in general, and hopefully something about themselves, too.

Mole experiences a few near death experiences, and also a few self-revelations. The first happens when Mole comes out of the Wild Wood, aided by Ratty, Badger and then the Otter (who knows all the paths):

As he hurried along, eagerly anticipating the moment when he would be at home again among the things he knew and liked, the Mole saw clearly that he was an animal of tilled field and hedge-row, linked to the ploughed furrow, the frequented pasture, the lane of evening lingerings, the cultivated garden-plot. For others the asperities, the stubborn endurance, or the clash of actual conflict, that went with Nature in the rough; he must be wise, must keep to the pleasant places in which his lines were laid and which held adventure enough, in their way, to last for a lifetime.

This category of self-revelation is commonly found in children’s books, where children go out into the world, have a dangerous adventure, and finally learn that they are safest at home. This is definitely a passage which Kenneth Grahame designed with children in mind. He’s taken adult readers to the floating world, but brings Mole back to childlike safety. The following chapter is titled “Dulce Domum” (Sweetly at Home). Note that we are only up to chapter five out of twelve. There is still plenty of time for Mole to have a real anagnorisis rather than a pat one meant to conclude children’s storybooks. Will he?

Read beyond the surface and The Wind in the Willows has elements of a transgression thriller. (A transgression plot always features the unmasking part of a story at this point.) IN this particular story, the ‘masks’ of Mole, Ratty and Toad come off to reveal their ‘true selves’. The story line involving Toad is the most comedic and obvious unmasking.

A transgression thriller is structured like this:

- Discontent — someone is unhappy about something

- Transgression with a mask — peculiar to comedy and thrillers

- Transgression without a mask — midpoint disaster when the mask is ripped off

- Dealing with consequences

- Spiritual Crisis — happens in almost every story

- Growth Without a Mask

Important to add: Transgression thrillers are very similar to transgression comedies. The structure is identical. The Wind In The Willows is also (mostly?) a comedy. (A comedy for adults, perhaps more of a thriller for Edwardian children who enjoyed seeing the childlike Toad get into constant trouble.)

Toad’s Transgression Plot:

- Discontent — Toad sees a motor-car and wants a motor-car. When he gets a motor-car and is arrested for being a public menace he is not exactly happy in prison.

- Transgression with a mask — Although we are much less inclined to see aristocrats as impressive people today (seeing only markers of privilege and systemic, historical oppression), in Edwardian England aristocrats were afforded respect simply because they were aristocrats. Toad is a childish, impulsive creature wearing the mask of genteel aristocracy. In order to escape from prison, Toad swaps this mask of gentility for another sort of mask (more obvious because it’s a literal disguise) and now he’s guised as a Washerwoman. This allows him a certain freedom. (Toad’s mask is comedically multilayered, because he’s even a man in a toad’s body.)

- Transgression without a mask — Toad reveals his true self fist when he is unable to manage some washing, and next when he snatches the steering wheel to take control of someone else’s motor-car (for the second time).

- Dealing with consequences — Toad manages to evade his enemies and makes it back to his friends on the river.

- Spiritual Crisis — This happens in almost every story, but Toad is not a spiritual sort of creature. The whole point is that Toad does not change.

- Growth Without a Mask — One thing changes in Toad’s circumstance, though. When Mole dresses up in the washerwoman’s clothing to get a rise out of the stoats, Toad is envious. I think he’s developed a taste for drag, and so has Mole.

Toad’s story is comedic.

The plot of Toad and his ridiculous dressing up, and Toad’s inability to suppress — and keep suppressed — his basest of urges is a more obvious, more comedic parallel outworking of what has internally (metaphorically, symbolically) happened to Mole on his interior adventure.

More subtly, Mole experiences a similar character arc to Toad. Mole’s growth is largely off the page and left to reader interpretation. He is initially bored with domesticity and decides to go on an adventure. On this adventure he falls in love with a different kind of life, one which takes place on the other side of the ‘river’: The erotic, transgressive side of society, which will acquaint him with his deepest desires, and where he will transgress gender expectations by living with another masculo-coded character.

By coincidence, or perhaps because of universal symbolism, Japanese language calls this pleasurable, heterotopian part of society Mole experiences on ‘the other side of the river’ the ‘floating world’ (homophonous with an older term from China, which translates roughly to ‘world of sorrow’).

The newer term at times was used to mean “erotic” or “stylish”, among other meanings, and came to describe the hedonistic spirit of the time for the lower classes. Asai Ryōi celebrated this spirit in the novel Ukiyo Monogatari (“Tales of the Floating World“, c. 1661):

“living only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.”

Wikipedia article on Ukiyo-e (art from the floating world)

Language Log has more to say on the concept of the floating world:

It is curious how the ukiyo that meant “world of worry and grief”, a Buddhist concept, is inverted to mean “world of diversion and pleasure”. One can still sense the connection between the two, however, since even (or particularly) when one is immersed in pleasurable pursuits, the evanescence of the moment lends a peculiar poignancy to one’s escapist epicureanism.

The term fúshì 浮世 (lit., “floating world”) already existed in medieval Chinese with the meaning of “ephemeral, mundane world”, so this notion would have been available for Japanese who wanted to make a pun with the ukiyo meaning “world of sorrow / worry”.

The notion of a sorrowful world (憂世), seen in texts from the latter part of the Heian period (794-1185) on, shifted to that of a floating world (浮世) in the late 16th century. But, of course, even when one writes 浮世, the older meaning of 憂世 is still accessible through the duosemic pun — because life is short and painful, it is best to float along and enjoy it. The pair of words is often pointed to as representative of the change in worldview from the medieval to the early modern.

Language Log

And I can’t help but think that the phrase ‘because life is short and painful, it is best to float along and enjoy it’ applies to Mole and Ratty in The Wind In The Willows. (To Toad it applies even more so, in its extreme.) If Mole had stayed home and finished white washing his walls he’d have been perfectly safe. You can’t ‘cross the river’ for adventure without the sorrow.

I also love the phrase ‘escapist epicurianism’, which describes The Wind In The Willows also. (Epicurianism: devotion to sensual enjoyment, especially that derived from fine food and drink.)

ON MASKS AND GENDER INVERSION AS GAGS IN STORYTELLING

I have thought at length about why I find gender inversion gags distasteful. (Scratch that: gender inversion gags are actively harmful.) After re-reading The Wind In The Willows, I’m guessing a number of contemporary storytellers are trying to pull off what Kenneth Grahame pulled off, but badly.

Why am I okay with Toad (and later Mole) dressing as a woman to get away with things, but disappointed at other, similar gags in later works? After further consideration, it comes down to a few big questions:

What is the cross-dressed character trying to get away with, exactly?

Why?

Why, exactly, is it funny? (If you can’t answer that, you haven’t thought deeply enough.)

To expand: Is the storyteller dressing their masculo-coded character as femme in order to subvert troubling, misogynistic tropes, or are they reinforcing them? There is of course a difference between drag and misogynistic guising. Unfortunately, too many contemporary storytellers are still not getting their heads around this distinction. It’s widely accepted that children’s literature can both construct and challenge societal norms. Whenever fictional characters cross-dress, they can reinforce norms (namely, stereotypes and prejudices) or they can (ocassionally) usefully challenge them.

I believe Kenneth Grahame’s Toad is in political drag, playing with society’s norms in a meaningful way within the text. His adventure dressed down as a trickster washerwoman pokes fun not so much at working class women, but at the patriarchal structure which keeps such women in their place. The trope can never be entirely problematic. No gag ever is. Toad’s transgression does punch down at middle-aged women who are so lacking in beauty privilege they pass as toads.

The woman moved nearer to him and peered under his bonnet keenly and closely. ‘Why, so you are!’ she cried. ‘Well, I never! A horrid, nasty, crawly Toad! And in my nice clean barge, too! Now that is a thing that I will NOT have.’

The Wind In The Willows. Of course Toad’s ‘mask’ must come off. It is a genuine Washerwoman who uncovers his trick. She can’t be fooled because she is the real deal. This gives some power back to her.

Throughout this escapade, Toad has not only masked his gender, he has also masked his social and economic status. He has inadvertently created an intersection of disadvantages for himself under the illusion that once he was out of prison, he’d be completely free in the world.

The washerwoman’s squat figure in its familiar cotton print seemed a passport for every barred door and grim gatewal; even when he hesitated, uncertain as to the right turning to take, he found himself helped out of his difficulty by the warder at the next gate, anxious to be off to his tea, summoning him to come along sharp and not keep him waiting there all night. The chaff and the humorous sallies to which he was subjected, and to which, of course, he had to provide prompt and effective reply, formed, indeeed, his chief danger; for Toad was an animal with a strong sense of his own diggnity, and the chaff was mostly (he thought) poor and clumsy, and the humour of the sallies entirely lacking.

The Wind In The Willows

The scene which follows shows Toad’s surprise and disappointment when he realises he has not only lost his own clothes, but all the money that goes into the pockets. It is only after he asks the train conductor if he can pay later that he realises it’s not just money he’s missing, but all credibility. He’s lost all of his social status and the intersection of poverty and womanhood is doing his head in. He’s never considered his own social status before.

Next he behaves as he imagines women behave — dramatically, to get what they want. This is often used in gender inversion gags. Kenneth Grahame makes sure the joke falls back on Toad, though, rather than (washer)women when the train driver makes a bargain: a ride for some washing. Privately, Toad has no intention of doing any washing, as this would be beneath him. He vows to send money, just as soon as his original status is restored. While male to female gender inversion gags commonly convey the message that women lie to get their own way, here Kenneth Grahame shows clearly, via exposition of Toad’s thoughts, that it is Toad himself who lies to get his own way.

Will he be brought down a peg? Hell no, he can’t stand living for any length of time as an ugly, poor Washerwoman (in which the beauty standards are higher for women). Toad has carnivalesque fun for a while, but jumps out of the Washerwoman role in an instant, possessed by the renewed desire to control a motor-car. Toad’s desire to control a motor-car represents a desire to control the world around him in general, in an aristocratic way. The gender inversion gag therefore also manages to punch up. Also, the fact that Toad can’t sustain his role highlights the illusory and performative nature of gender. In other words, Toad’s case successfully defamiliarises gender by playing with its markers, encouraging readers to think about what it really means to be a ‘man’. Grahame has further defamiliarised gender by portraying this ‘man’ as a ‘toad’.

Importantly, Kenneth Grahame avoids the two most egregious tropes associated with male-to-female cross-dressing in fiction:

- Although Toad doesn’t come up with it himself (due to him being so pathetically melodramatic), Toad cross-dresses by his own volition.

- Toad is not shamed for being a woman once the clothing inevitably comes off. He is shamed for being the exact toad that he is.

This removes much of the gender shame of too many cross-dressing gags. Moreover, when Toad finally casts aside his washerwoman disguise, Kenneth Grahame’s narrator says that the ‘dodgings and evasions were over, and he could lay aside a disguise that was unworthy of his position and wanted such a lot of living up to’.

It is via Toad’s focalisation that the washerwoman’s clothing is ‘unworthy of his position’. Toad’s high opinion of himself has been suffciently lampooned. We also know that the low-status washerwoman takes ‘a lot of living up to’. The washerwoman (standing for femme characters in general) has not been shamed during Toad’s escapade. Shame is the key issue with gender inversion gags.

I would love to know if Kenneth Grahame himself was interested in transgressing gender binaries via clothing. Toad could be a humorous outworking of some deep desire in the author. We’ll never know. Suffice to say, even the imaginative desire to transgress gender via clothing choices is still representative of some kind of desire. To transgress gender via clothing is symbolic of transgressing the strictures of gender more generally. If the joke’s on anyone, it’s on people who can’t see through a thin veneer of disguise:

What utter idiots all the people must have been to have ever mistaken him for one moment for a washerwoman.

The Wind In The Willows, “Like Summer Tempests came his Tears”

THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT

It has more commonly been suggested that Kenneth Grahame was distancing himself from something else:

The Wind in the Willows can be read as Kenneth Grahame’s attempt to distance himself from the excesses of the Aesthetic Movement with which he had once been identified. … even the most reliable of the river-bank’s band of male friends, Water Rat, must be drained of any proclivity for untrustworthy Wildean “passions.”

Oscar Wilde at Toad Hall: Kenneth Grahame’s Drainings and Draggings, U. C. Knoepflmacher

Around the time The Wind In The Willows was published, Modernists and Impressionists were writing short stories with epiphanies that didn’t ‘stick’. These writers were challenging the idea that humans can truly change, and even if they can, it doesn’t happen over the course of a short narrative. Many character arcs and moral lessons from the 1800s seemed freshly contrived to a modern audience. In contrast, Leila at the end of Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist “Her First Ball” decides to forget about her encounter with the creepy old man. Some commentators call this category of anagnorisis an ‘antiepiphany’.

Kenneth Grahame may have noticed the emergence of the antiepiphany in storytelling, as he seems to be lampooning the development via the character of Toad. Badger is the patriarchal ‘narrator’, made manifest by insertion into an actual story. Badger tries to teach Toad a lesson about safe driving by lecturing him in Toad’s smoking room, but it doesn’t stick:

‘There’s only one thing more to be done,’ continued the gratified Badger. ‘Toad, I want you solemnly to repeat, before your friends here, what you fully admitted to me in the smoking-room just now. First, you are sorry for what you’ve done, and you see the folly of it all?’

There was a long, long pause. Toad looked desperately this way and that, while the other animals waited in grave silence. At last he spoke.

‘No!’ he said, a little sullenly, but stoutly; ‘I’m not sorry. And it wasn’t folly at all! It was simply glorious!’

‘What?’ cried the Badger, greatly scandalised. ‘You backsliding animal, didn’t you tell me just now, in there—’

‘O, yes, yes, in there,’ said Toad impatiently. ‘I’d have said anything in there. You’re so eloquent, dear Badger, and so moving, and so convincing, and put all your points so frightfully well— you can do what you like with me in there, and you know it. But I’ve been searching my mind since, and going over things in it, and I find that I’m not a bit sorry or repentant really, so it’s no earthly good saying I am; now, is it?’

The Wind In The Willows, Mr Toad

This chapter is left out of many bowdlerlised editions of The Wind In The Willows, but when Mole and Ratty go on their mission down the marvellous river, ostensibly to rescue Portly, the young otter, they have a sublime experience on a hidden island in the middle of the river. They see a vision of muscular Pan, the demigod of nature, who disappears, leaving behind the corporeal young Portly. Mole and Ratty deliver the otter back to his parents forthwith. But not before Mole and Ratty are made to forget all that just happened. I fail to read this as anything other than post-coital bliss.

‘I feel strangely tired, Rat,’ said the Mole, leaning wearily over his oars as teh boat drifted. ‘It’s being up all night, you’ll say, perhaps; but that’s nothing. We do as much half the nights of the week, at this time of the year. No; I feel as if I had been through something very exciting and rather terrible, and it was just over; and yet nothing particular happened.’

‘Or something very surprising and splendid and beautiful,’ murmured the Rat, leaning back and closing his eyes. ‘I feel just as you do, Mole; simply dead tired, though not body tired. It’s lucky we’ve got the stream with us, to take us home. Isn’t it jolly to feel the sun again, soaking into one’s bones! And hark to the wind playing in the reeds!’

‘It’s like music — far away music,’ said the Mole nodding drowsily.

The Wind In the Willows, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”.

Yet every single instance in this book I think, “Well, that was clearly obviously really a sex scene thinly disguised (mostly with food)” I imagine Grahame the author thinking, “Oops, that was a bit obvious”. He then throws some child character(s) into the action, because there’s nothing like the sudden appearance of children to puncture a certain mood. I can almost hear Grahame chanting to himself, Toadlike, “I’m writing a children’s book, a children’s book… must inject children.”

Chimeras make for surprisingly common fantasy fodder. We know this from art. Despite the mission thrown in for children (the rescue of a child) this chapter in The Wind In The Willows is very-super-obviously an overnight sex romp, which culminates in a sexual awakening.

Also, if you thought a human-talking-animal combo was a bit too cross-genre, the appearance of a Greek demigod makes it even more so. I mean, this is almost on a par with Santa turning up in Narnia.

As for Toad’s epiphany, he says, “I’ve been a conceited old ass”, and in the moment, he means it.

NEW SITUATION

We’ve already been shown that Toad vacillates between manic and contrite, so it’s clear Toad will continue in his usual clowning manner. As Toad himself noted several times on his adventure, he always comes up trumps. We know that’s going to happen, too, not because this is a children’s book but because Toad has a significant amount of privilege behind him, and the blue bloods get away with blue murder.

Sure enough, Toad goes against Ratty’s advice right away and returns to his mansion full of gun-toting squatters, risking his life and Ratty’s nice blue and white boat. Once again, Toad is contrite, ‘The Toad saw at once how wrongly and foolishly he had acted. He admitted his errors and wrong-headedness and made a full apology to Rat for losing his boat and spoiling his clothes.’ The (lampoon of) the antiepiphany.

We learn via Toad and Ratty’s conversation that Mole and Badger have been camped out around Toad’s manor, trying to protect it from weasels.

Over the course of this story, Ratty has been transformed from a Head character into a ‘poet’. The plan-making character is now the Badger. (This transformation happened after Ratty met the navy man.)

After this climax, the four animals continued to lead their lives, so rudely broken in upon by civil war, in great joy and contentment, undisturbed by further risings or invasions.

The Wind In The Willows, “The Return of Ulysses”

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Mole and Badger failed at their one task of keeping Toad Hall free of weasels. I’m guessing they were emotionally involved with each other.

RESONANCE

The Wind in the Willows is a hugely important and influential book, and changed children’s literature forever.

To take just one example, Kenneth Grahame influenced J.R.R. Tolkien. The Wind In The Willows was written about 30 years before The Hobbit. Tolkien read Grahame’s work and is known to have enjoyed it. Tolkien was indirectly influenced by Grahame’s story e.g. Mole lives in a ‘Hobbit’ hole, and all of these creatures are basically humans with extra fur setting off on a mythic adventure for homosocial bonding.

In Britain this story was recently used as the basis for an environmental campaign, voiced by Sir David Attenborough. The animals are in danger of losing their homes.

There have been re-visionings of The Wind In The Willows for example Wild Wood (1981).

As Jan Needle’s alternative view of Grahame’s novel, Wild Wood (1981) suggests, books written for children often only subtly disguise the adult issues of the authors who write them. Needle designed her alternative version of The Wind in the Willows from the viewpoint of the Wild Wooders, and reveals Grahame’s classic to be riddled with the unease between the comfortable upper middle classes and those who live outside their world — the stoats, weasels, washerwomen, and jailer’s daughters of the world.

The Enemy Without: Post-1945 British Animal Fantasy and the Safety of Home Space, Karen Sands-O’Connor

I’m sure there’s plenty of fan fiction out there, as well.

This may seem unrelated at first, but when I think of the two main plotlines of The Wind In The Willows: first Mole’s, then Toad’s, I recall anti-binge drinking TV campaigns of the 1990s and early 2000s. They were divided by gender.

The message for teenage girls: If you get drunk at a party, you risk regrettable sexual encounters with boys. (Or any sex at all, actually). Cf. Mole.

The message for teenage boys was different: If you get drunk, you risk driving a car and killing yourself, and possibly others as well. Cf. Toad.

With recent seismic shifts in societal attitude towards rape culture, I hope it’s not necessary to outline the problems with that 1990s messaging. Insofar as similarities go, this classic Edwardian animal story as well as the 1990s anti alcohol messaging was all about the consequences of losing control. The difference for Mole is that, for him, losing control results in unbridled joy, and a level-up of comfort in his life.

Header: The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Graham. Methuen & Co., London. Second Edition. 1918

RELATED

ON AMPHIBIANS

Herpetologists Discover Species Of Frogs That Evolved To Spontaneously Grow Top Hat And Cane is, of course, an Onion headline.