Flight is amazingly common in children’s stories. Several other motifs should be considered symbolically similar:

FLOATING AS FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

Characters might hold onto helium balloons, levitate by magic or by supernatural means. A picture book example of floating can be seen in “Outside Over There” by Maurice Sendak, in which Ida floats backwards out the nursery window, then floats through the fantasy landscape as if she’s underwater. Gravity works differently in this imaginary world of hers, in which her little sister was kidnapped by goblins.

An adventure about a group of kids with uncontrollable abilities!

Emerson can float…he just can’t do it very well.

His uncontrollable floating is his RISK factor, which means that he deals with Reoccurring Incidents of the Strange Kind. The last place Emerson wants to be is at a government-mandated summer camp for RISK kids like him, so he’s shocked when he actually starts having fun at camp—and he even makes some new friends.

But it’s not all canoeing and capture the flag at Camp Outlier. The summer of fun takes a serious turn when Emerson and his friends discover that one of their own is hiding a deadly secret that puts all of their lives in danger.

It’s up to the Red Maple boys to save themselves—and everyone like them.

Perhaps related to this is the trope throughout Irish and Scottish fairy legends of women floating while giving birth. As Diane Purkiss says, ‘passage is rite of passage, reflecting the dangers of childbirth’. The floating as childbirth metaphor may also indicate the wish to leave a very painful experience.

GOING TO A HIGH PLACE AS FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

Characters might climb a mountain, a tall building, a tree or treehouse. In children’s book world, Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton’s tree house series are mega bestsellers in Australia.

Treehouses feature often in children’s stories. In Dav Pilkey’s popular Captain Underpants series, the heroes George and Harold write comics in their treehouse and retreat to it when things get out of hand, to regroup and create their way out of trouble. There are, of course, Tolkien’s Ents, the walking trees who fight on the side of good against Sauron and his army. Or Dr Seuss’s Lorax, who guards the Truffula trees from devastation. Ents and the Lorax are guardians of the ecosystem. When they act we know that something is badly out of kilter — in these cases in the fight between good and evil.

Mention Enid Blyton’s Faraway Tree stories, meanwhile, and many a grown-up gets misty-eyed. Mary Pope Osborne’s Magic Tree House series has been going strong for 25 years, and has nearly 100 titles. Carter Higgins’s Everything You Need for a Treehouse helps you get kitted out for your own woodland home. And mythology is full of trees.

Elizabeth Hale and Lynnette Lounsbury

Roger and Lyra on the roof in Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights/The Golden Compass.

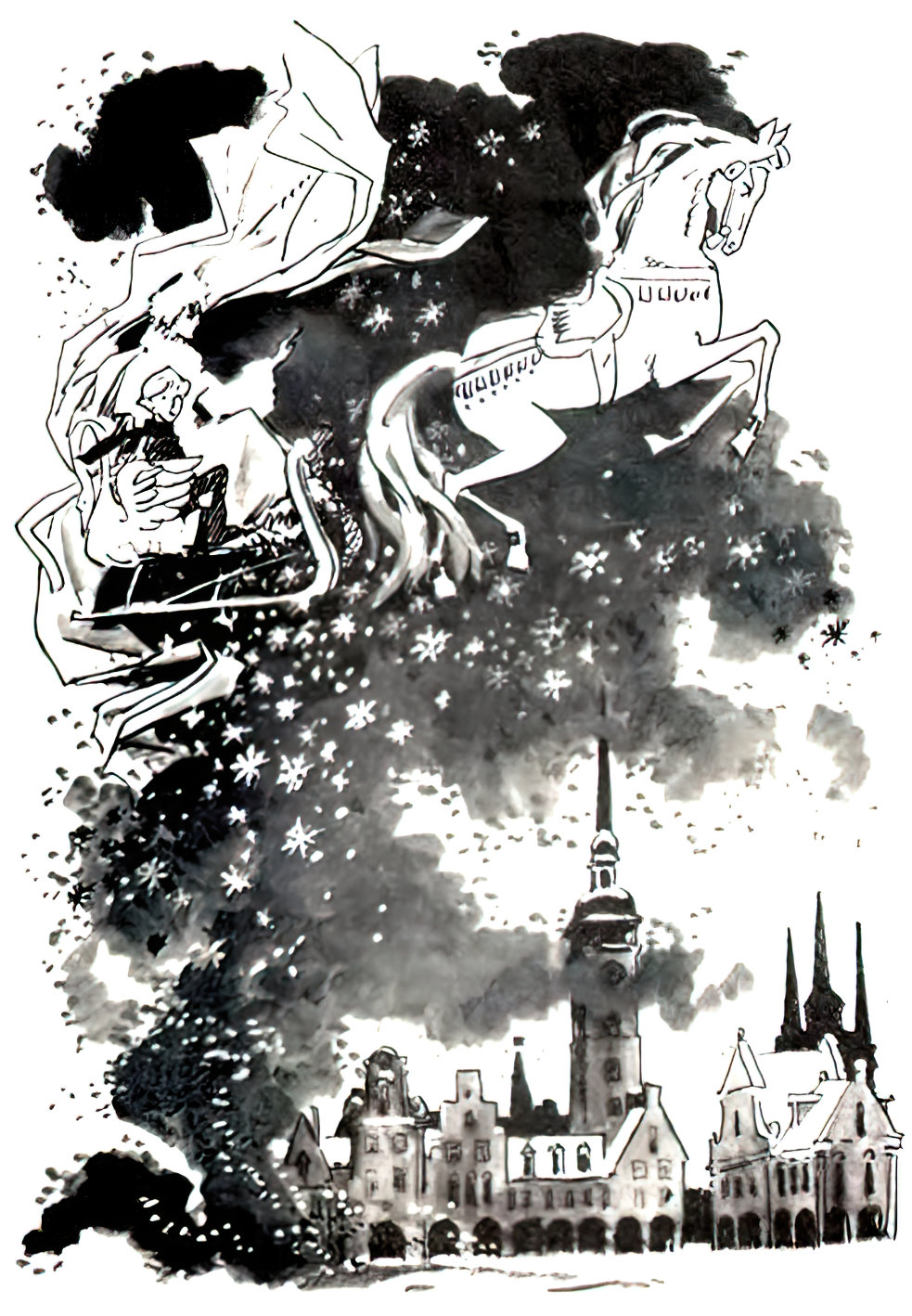

Santa Claus is famous for flying through the air in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, settling upon roofs. The Santa Claus story would not be quite so magical if he journeyed from place to place by Toyota Corolla and pulled up in the driveway.

Dr. Seuss loved to vary the altitude of his illustrations, with scenes set on mountains, clifftops, hills trees and whatever fantastical contraption he could dream up. I Had Trouble Getting To Solla Sollew is a good example of that. While his characters rarely fly, the risk of toppling adds to the drama and narrative drive. His characters are often mid-action, leaping and tumbling through the air.

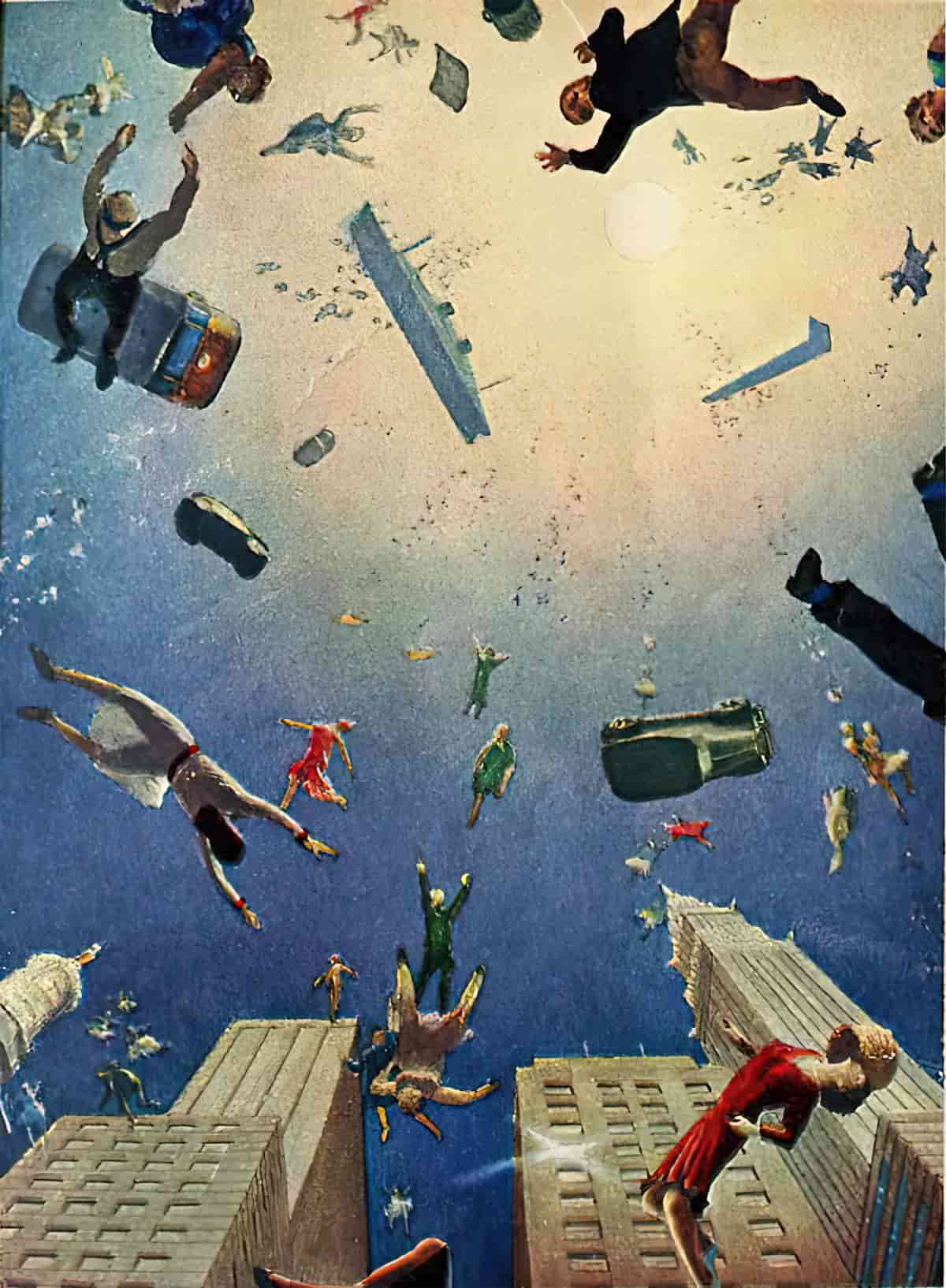

Since King Kong climbed to the top of the Empire State Building in 1933, the movies have often relied on skyscrapers as a tense setting for action thrills. And the buildings, along with studio ambitions, keep getting higher.

New York Times

HOVERING AS FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

Examples of hovering is easier to find in a subgenre in African American books.

Hover-flying may be considered a sub-genre within African-American picture books.

- Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold (1991)

- Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky (1992)

- Wings by Christopher Myers (2000)

- Fly! by Christopher Myers (2001)

This hover-flying might be interpreted as expressions of personal autonomy and social responsibility. Hover-flying may also be a metaphor for migration (exodus narratives), utilizing a vertical rather than horizontal way of defamiliarizing a setting such as a poverty-stricken South.

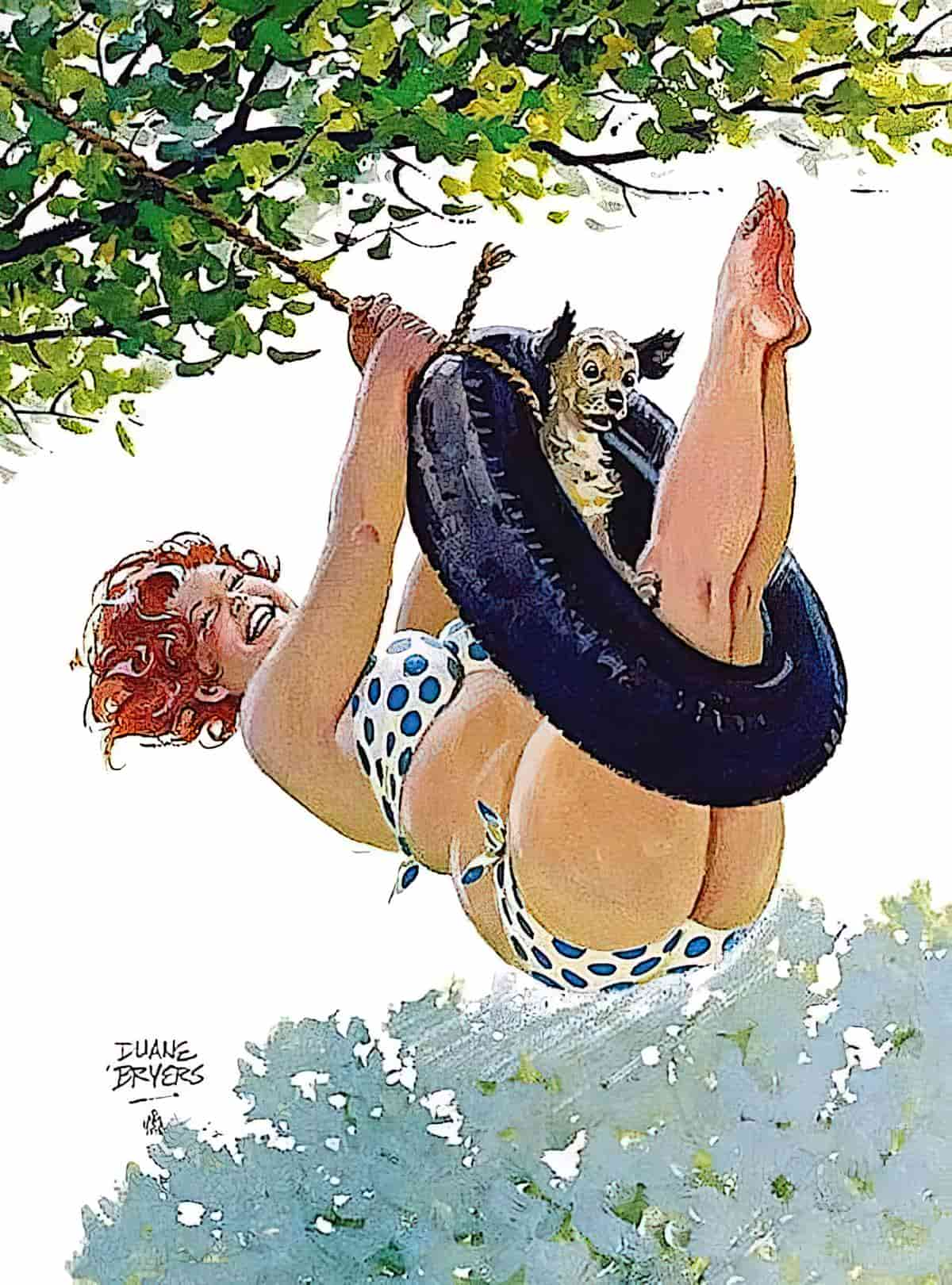

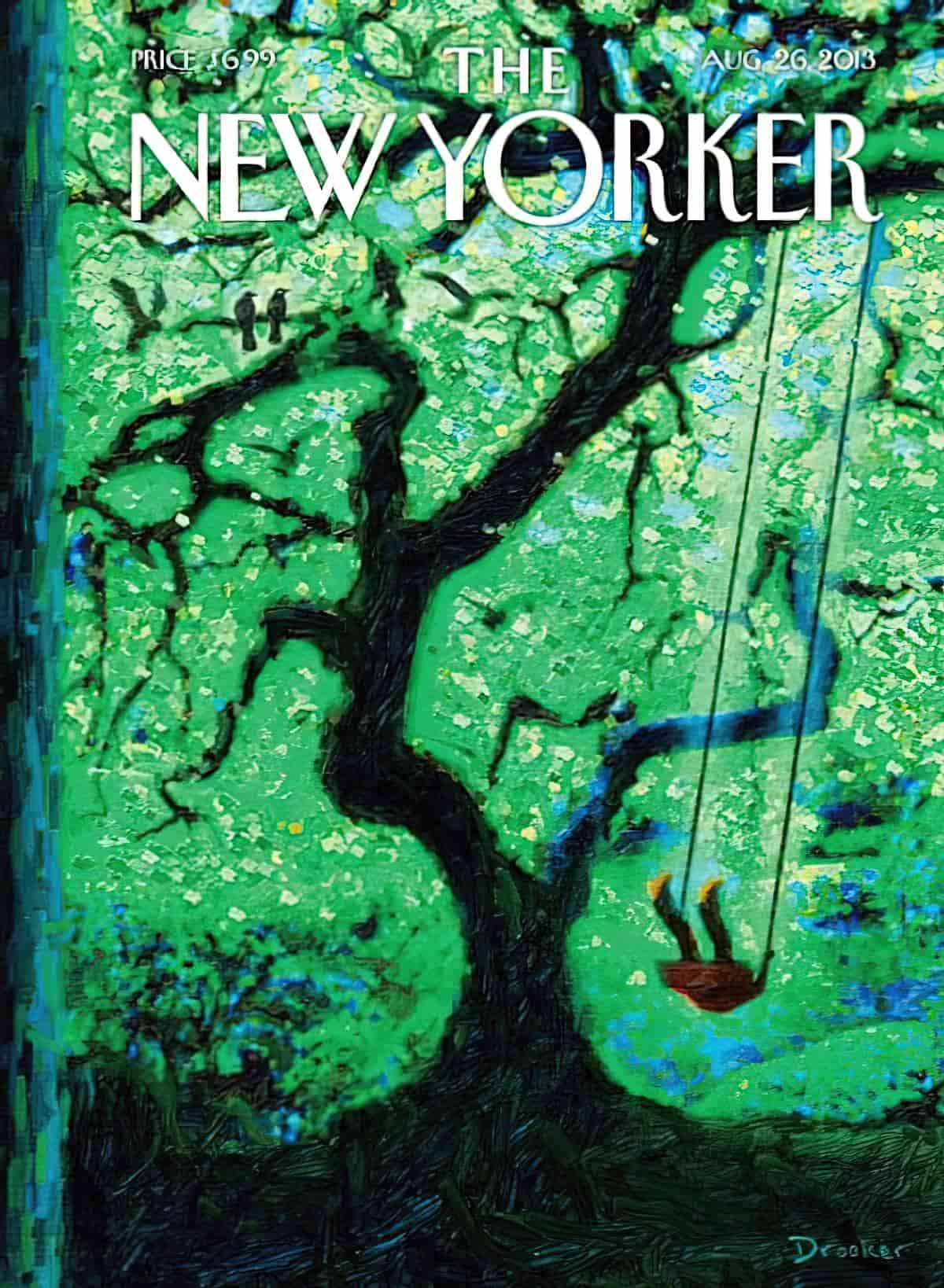

THE SWING AS SIMULATION OF FLIGHT

LEAPING AND JUMPING AS FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

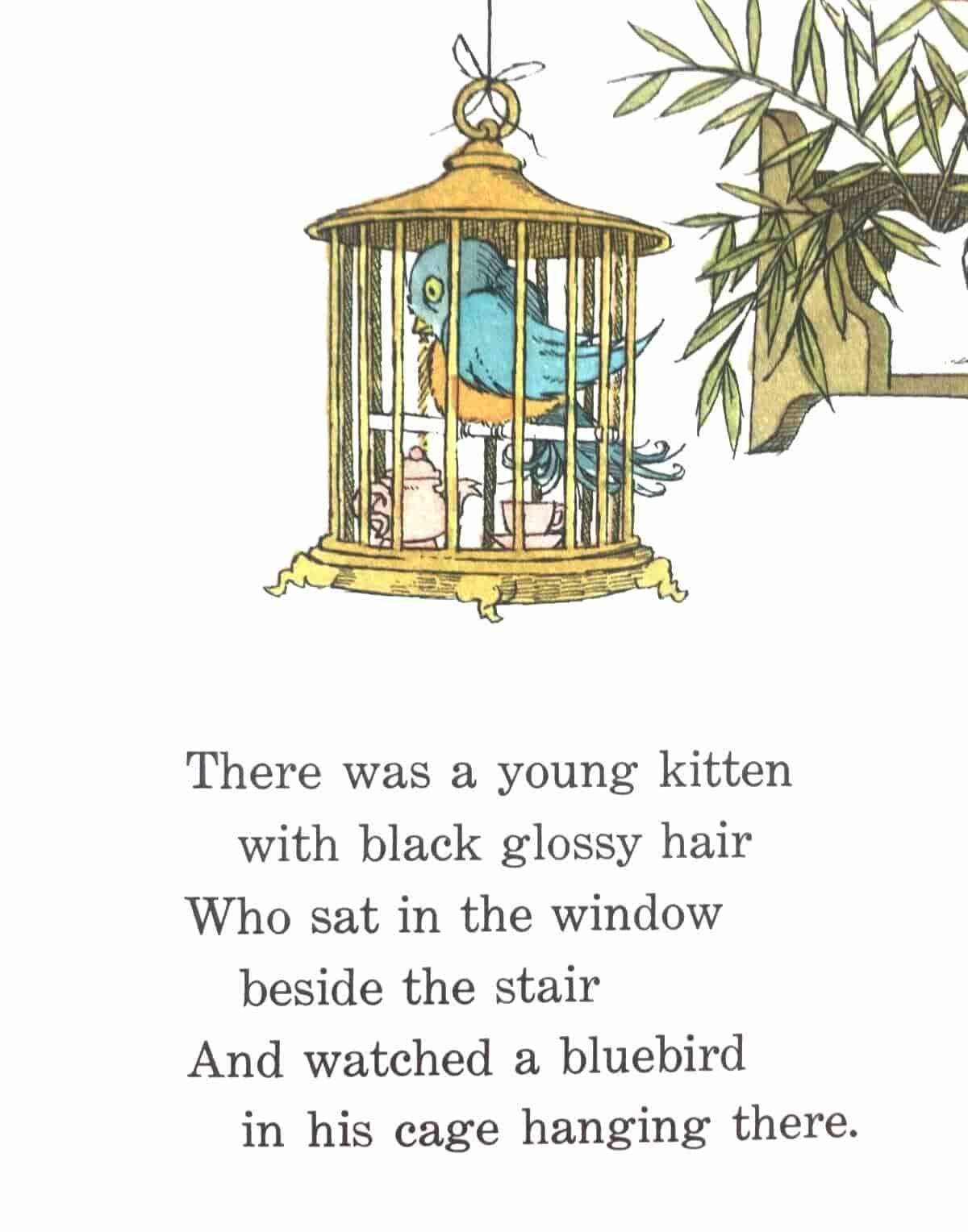

In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s fourth book for children, On The Banks Of Plum Creek, Laura and Mary jump with unrestrained joy off a stack of hay (until they’re told not to by their father). This contrasts with later chapters in the book where the outdoorsy Laura finds it difficult to concentrate in class, where she is required to sit still, restrained like a caged creature.

THE FAIRYTALE CHASE AS FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

There is a link between being chased and flying in dreams, which makes its way into stories. It makes sense that stories are influenced by dreams.

Christopher Vogler has this to say about how flight doesn’t always mean actual flying, and names the chase scene as flight-adjacent symbolism:

Fairy tales include a chase that involves a whimsical transformation of objects, known as the magic flight motif. In a typical story a little girl escapes from the clutches of a witch with the help of gifts from animals she’s been kind to. The girl throws down the gifts one by one in the witch’s path and they magically transform into barriers that delay the witch. A comb becomes a thick forest that slows the witch while she gobbles it up. A scarf becomes a wide river which she has to drink.

Joseph Campbell gives several illustrations of magical flights, and suggests the motif stands for a hero’s attempts to stall the avenging forces in any way possible, by throwing down “protective interpretations, principles, symbols, rationalizations, anything…(to)…delay and absorb” their power.

What the hero throws down in a chase may also represent a sacrifice, the leaving behind of something of value. The little girl of the fairy tales may find it hard to part with the lovely scarf or comb given by the animals. Heroes of movie adventures sometimes have to decide what’s really important, and toss money out the window to slow their pursuers and save their lives. [Joseph] Campbell cites the extreme example of Medea. Escaping with Jason from her father, she had Jason cut up her own brother and toss his pieces into the sea to delay the pursuit.

The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters

Before Vogler, Vladimir Propp categorised 31 functions of fairy tale, dividing fairytales into four main sections. In the fourth section the hero returns home, having already gotten the treasure. But there’s someone chasing them. It’s not worth their while to stop and fight at this point, so they run like the wind. Fairytales always end happily, so the hero needs to get away. Fairytale storytellers of course make use of flight to allow their victorious heroes a safe return.

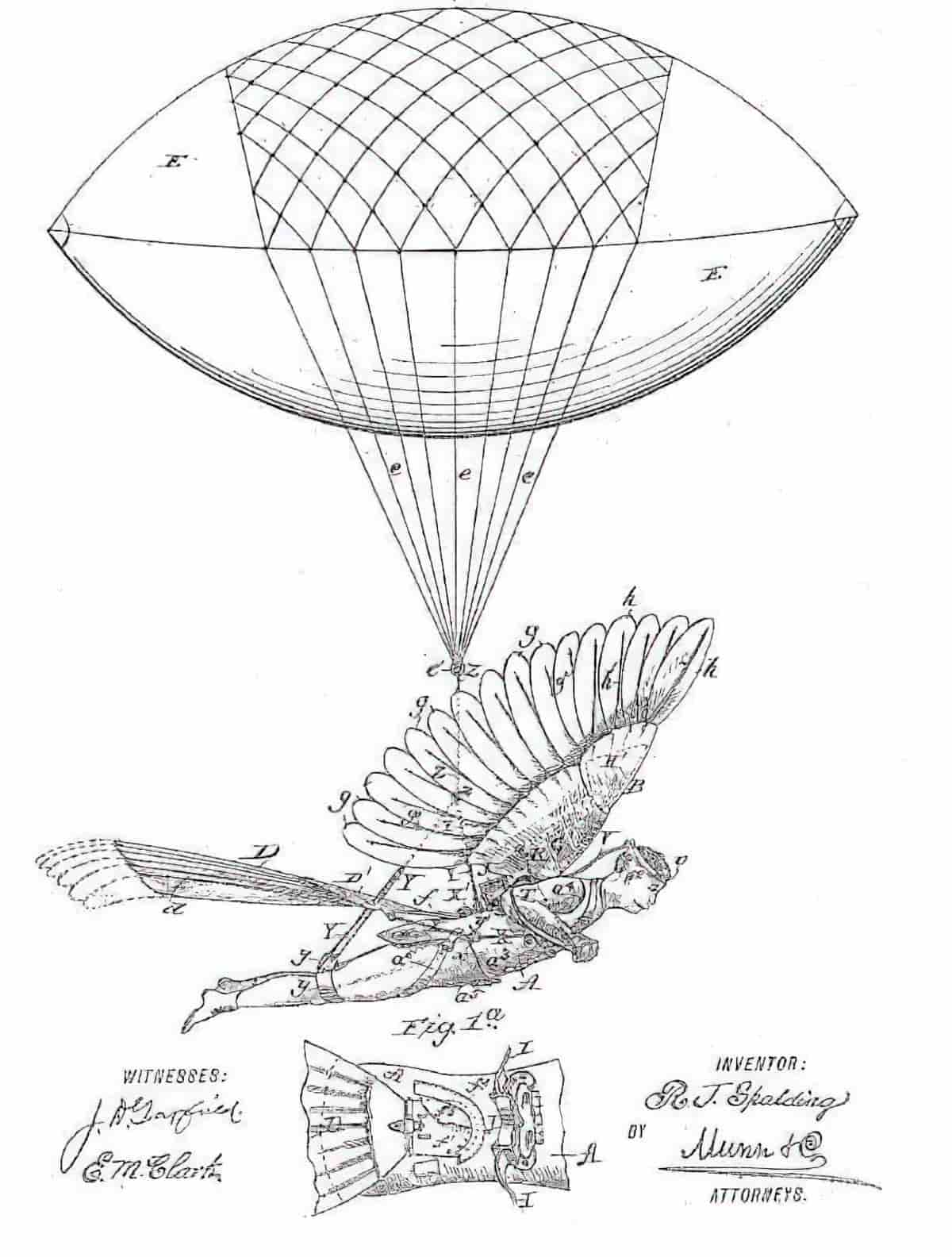

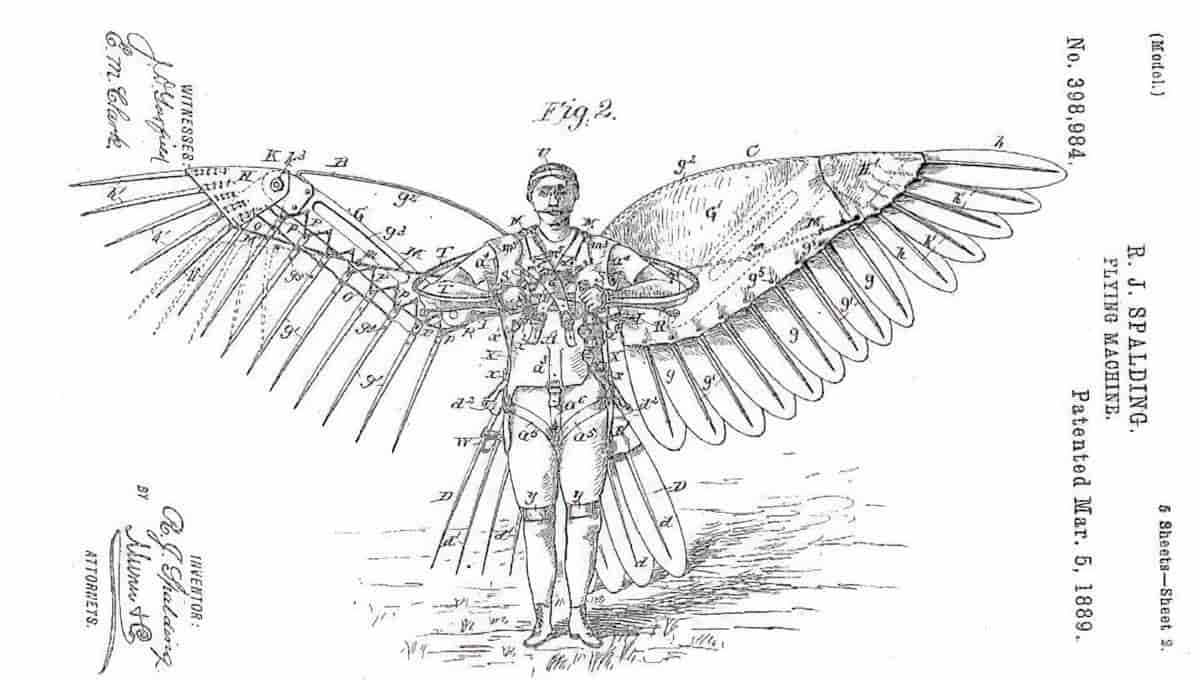

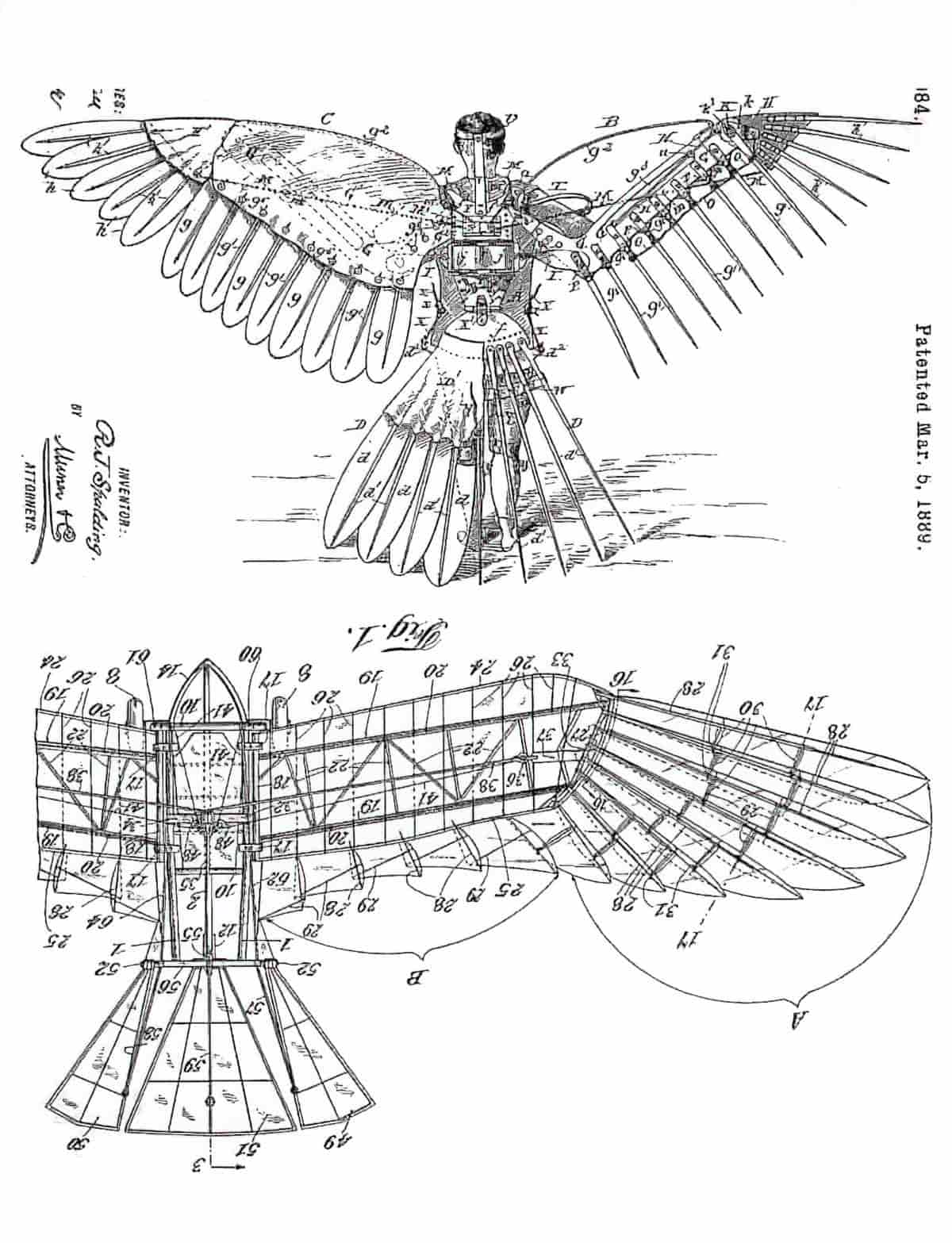

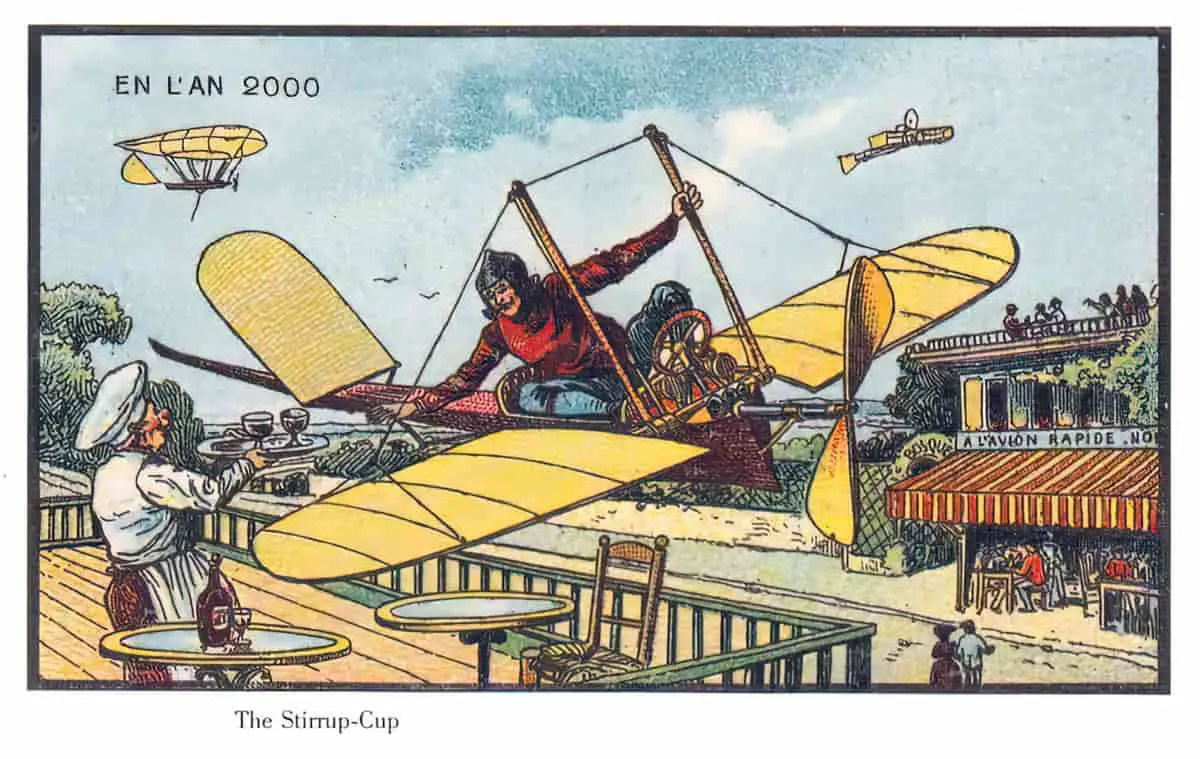

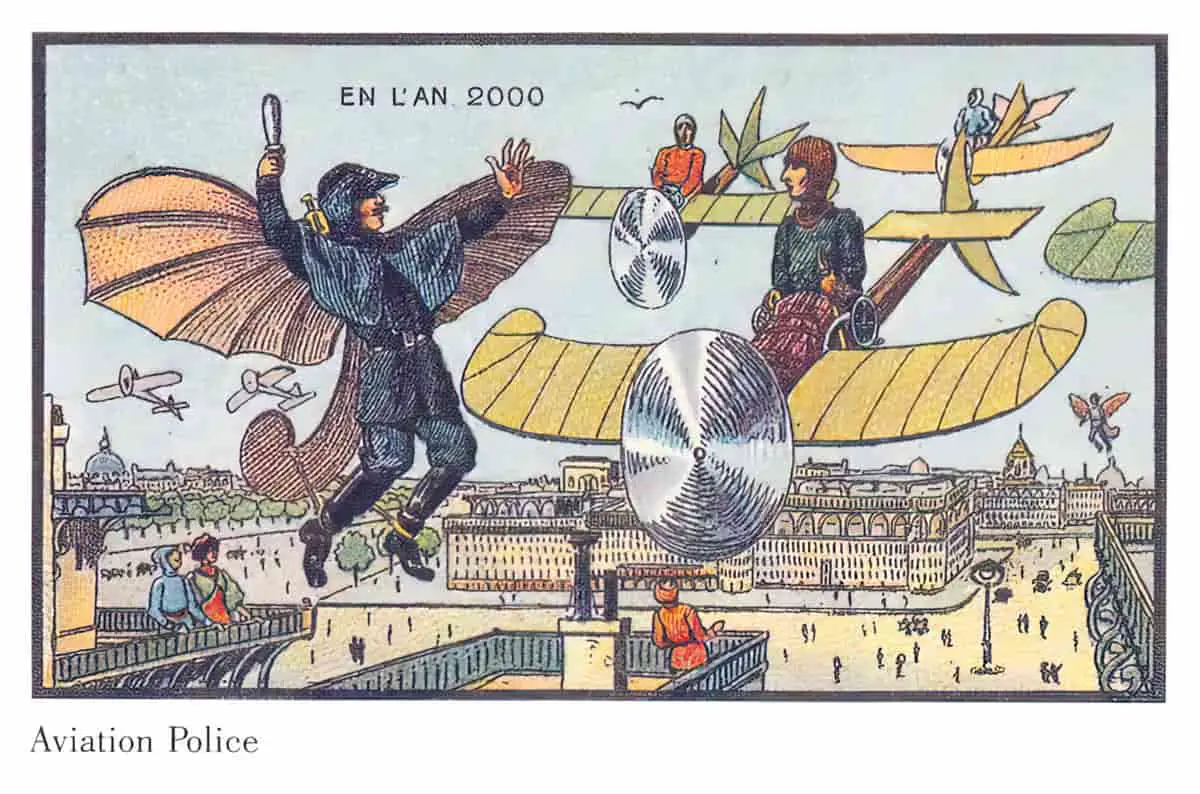

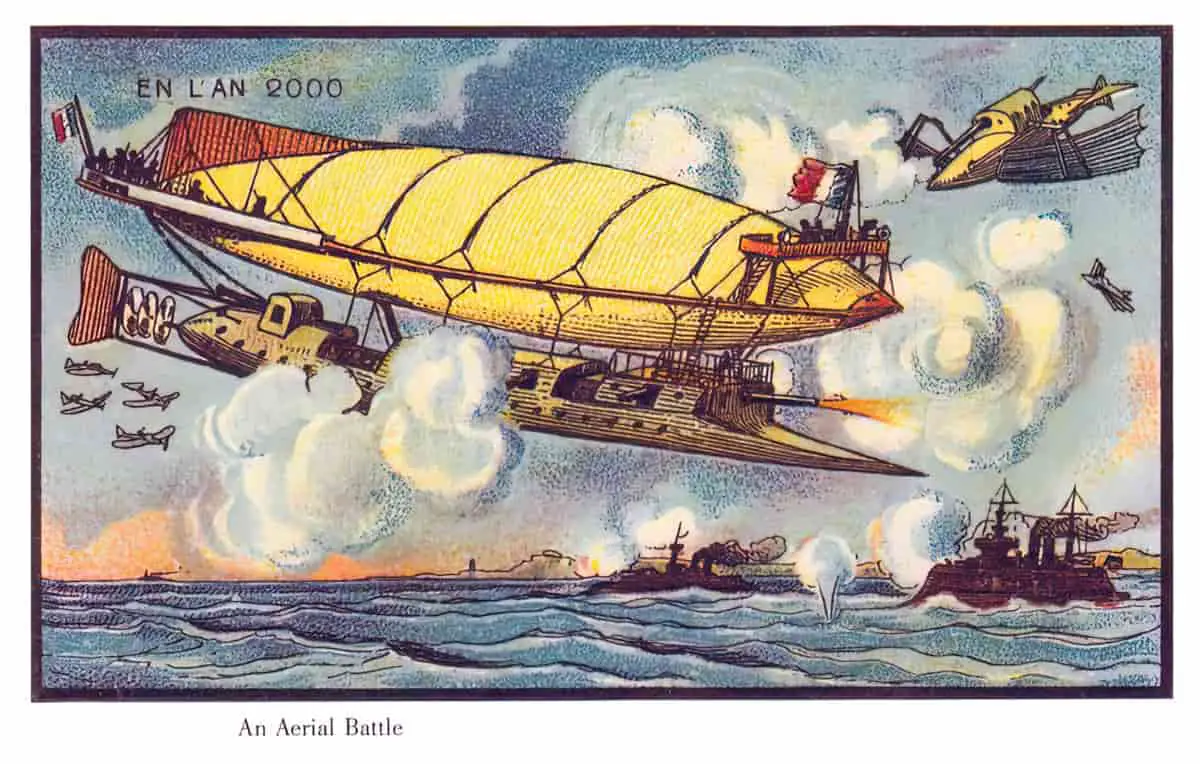

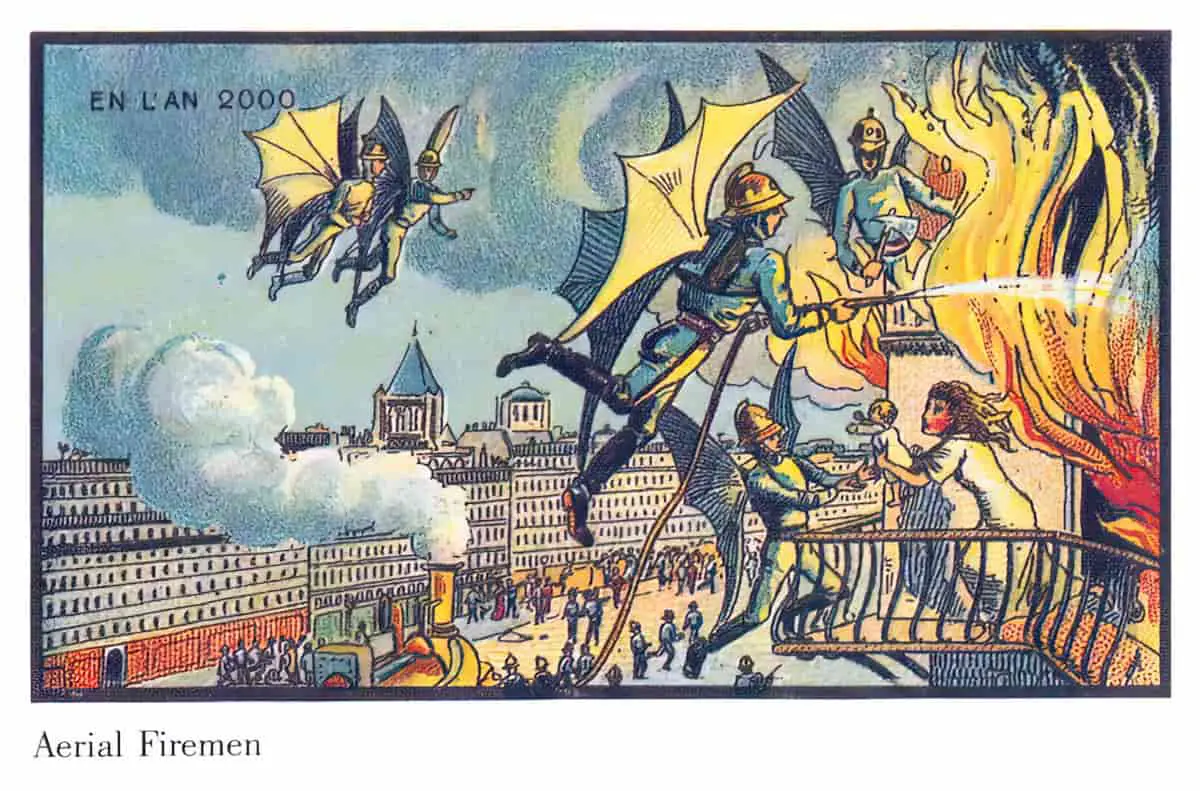

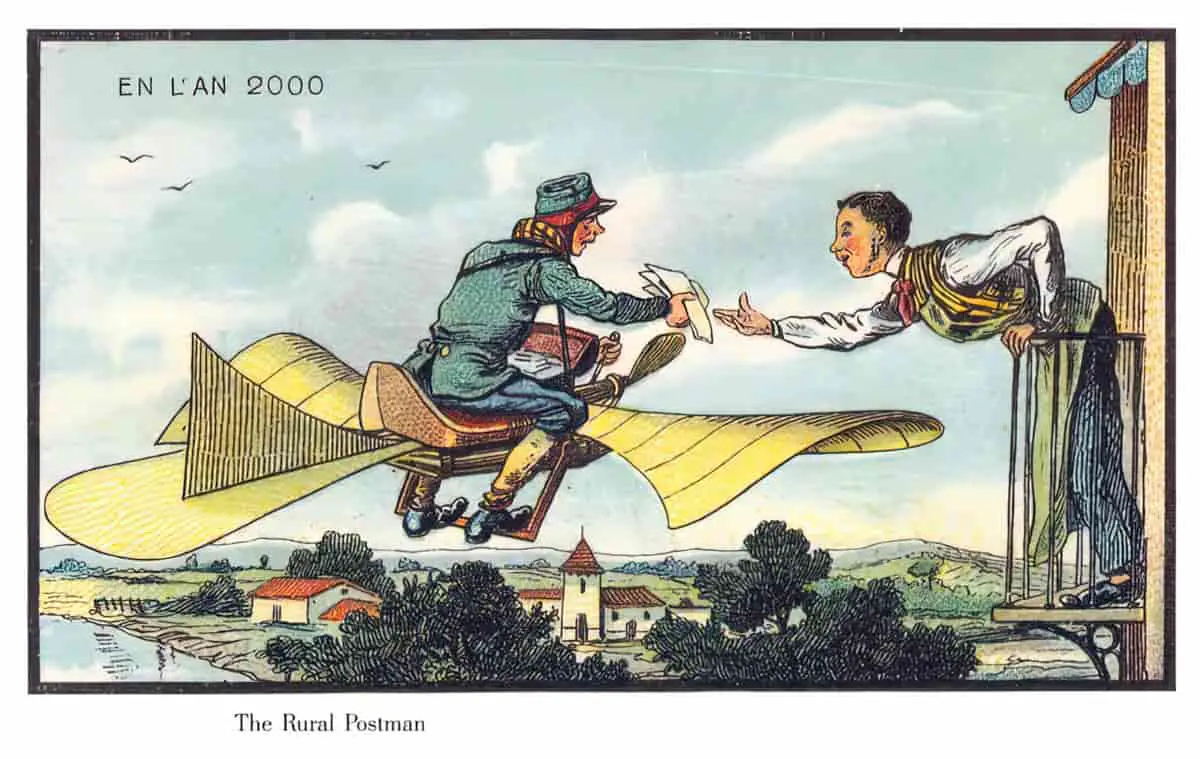

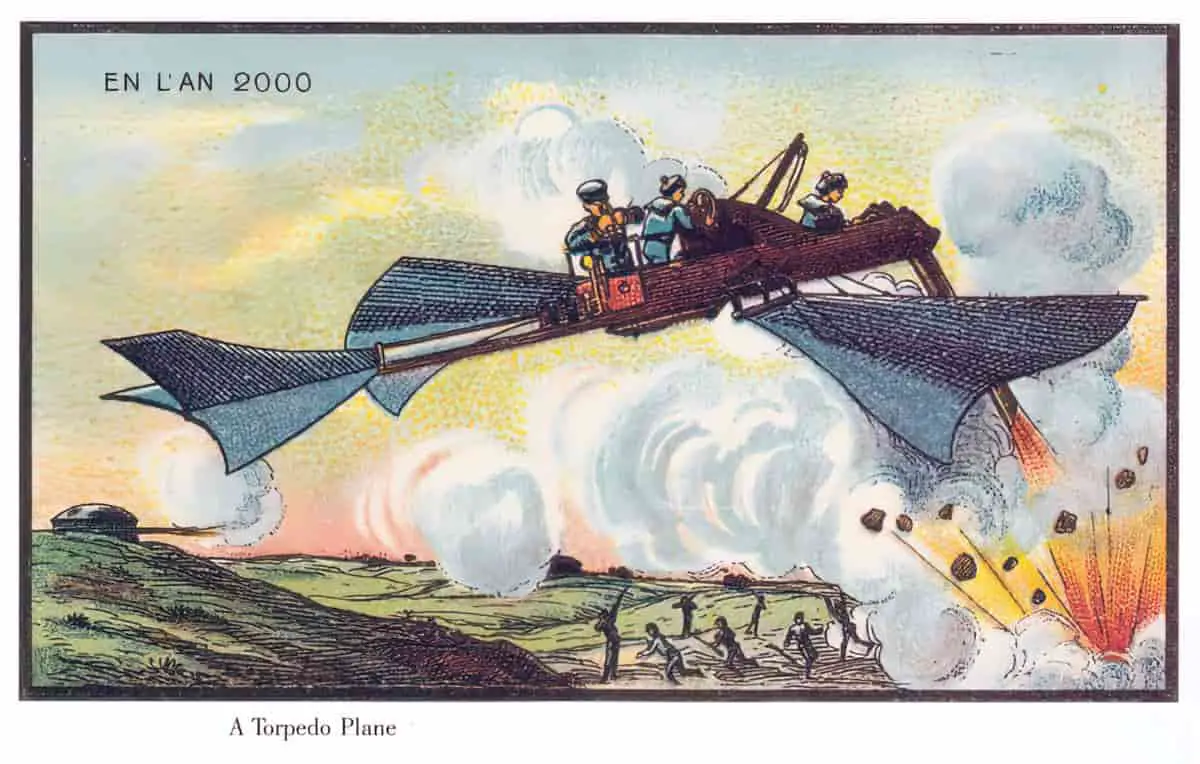

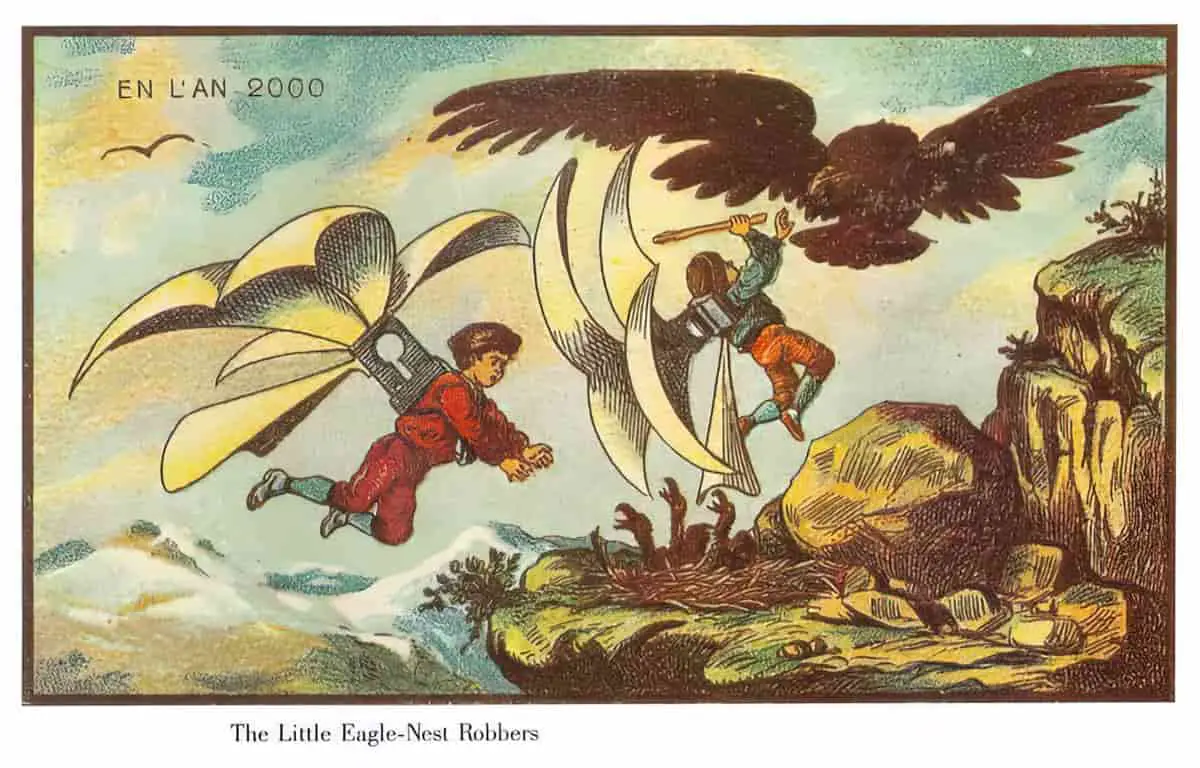

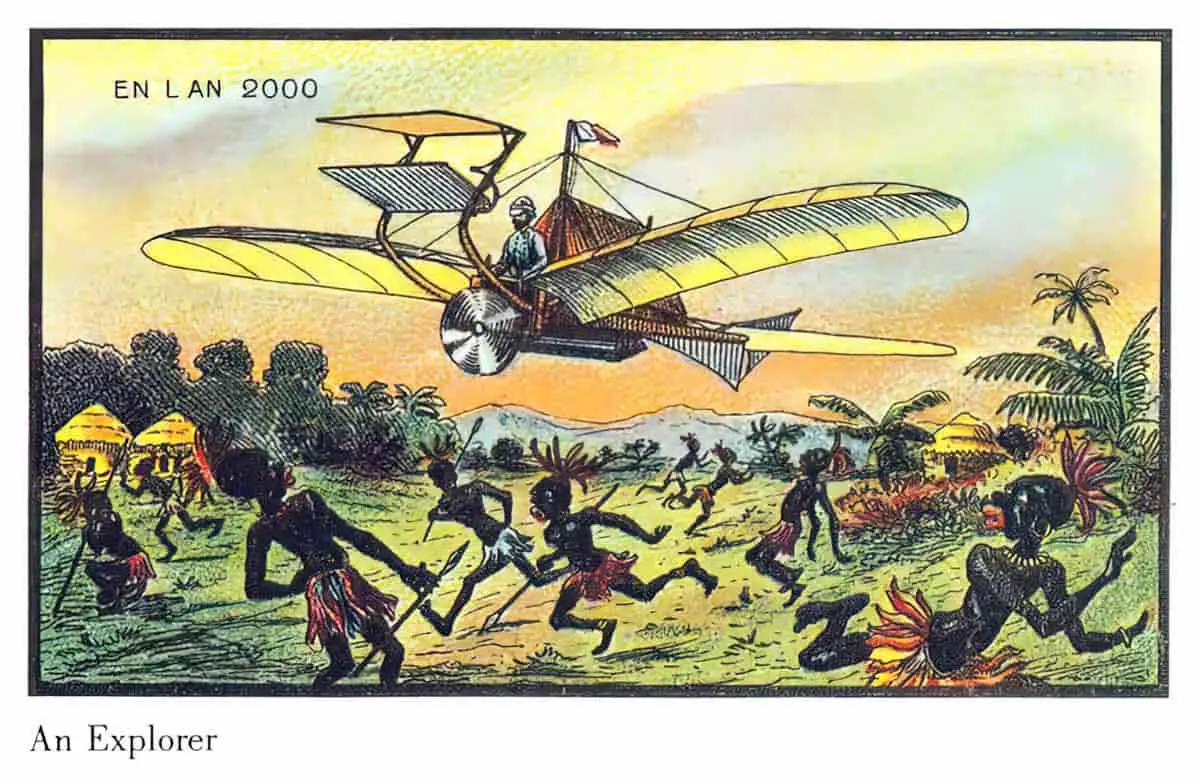

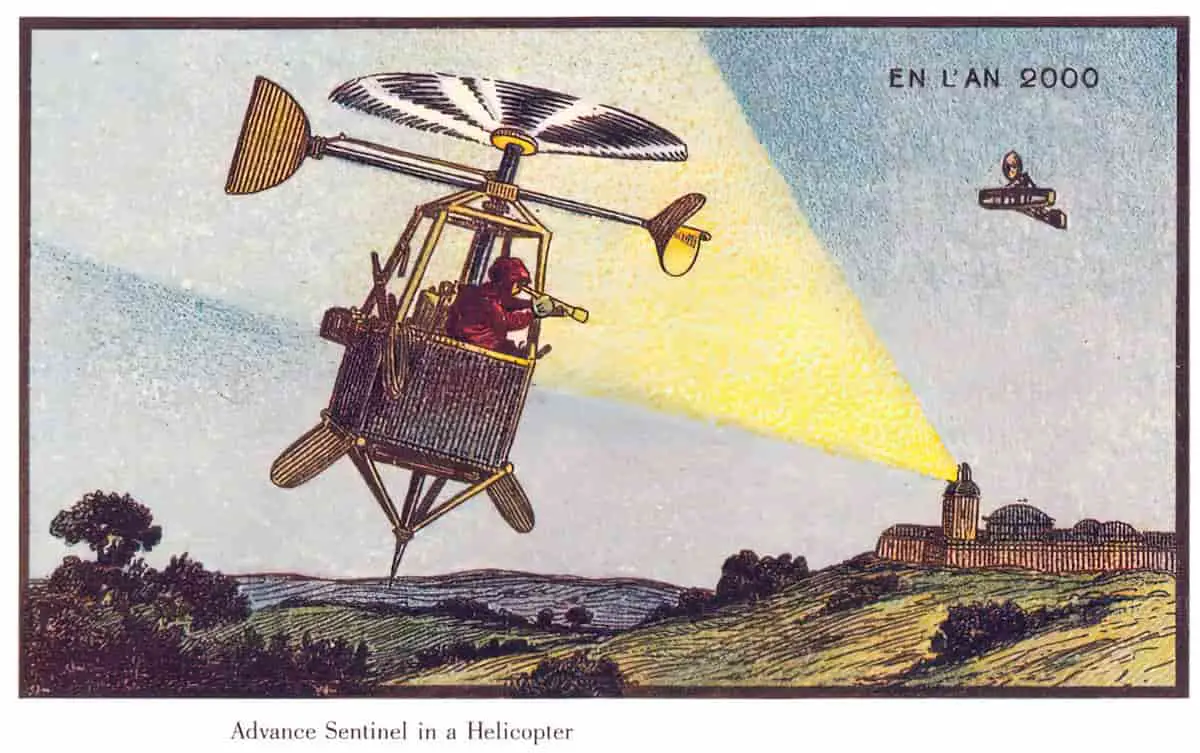

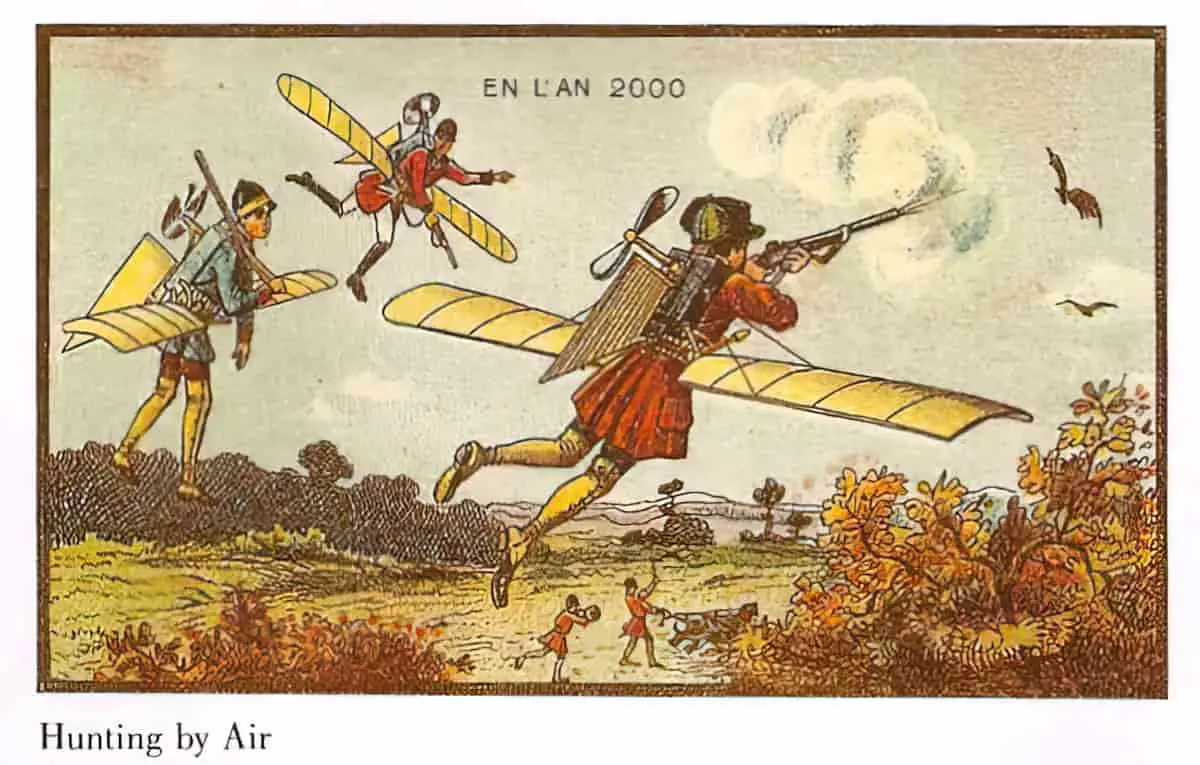

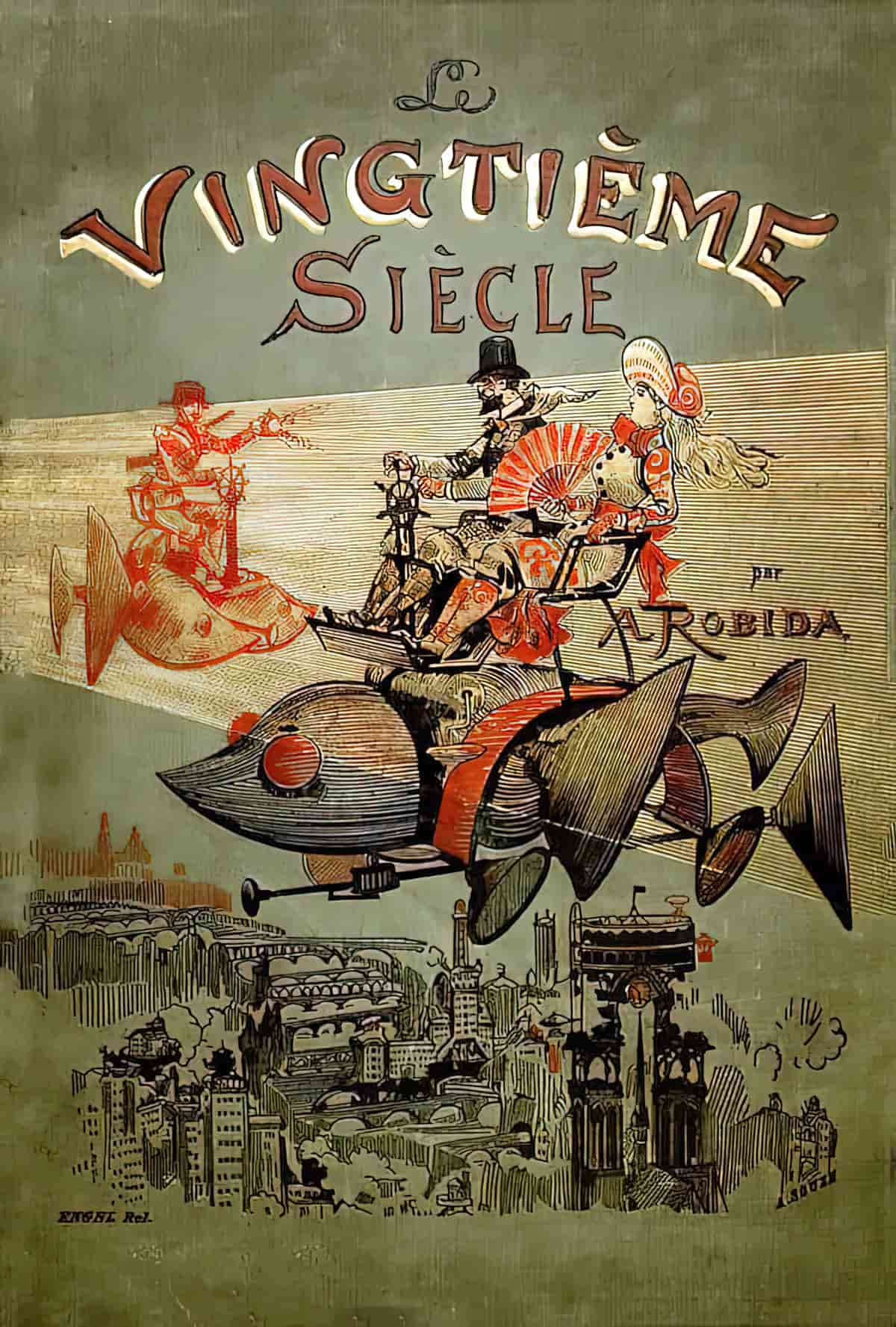

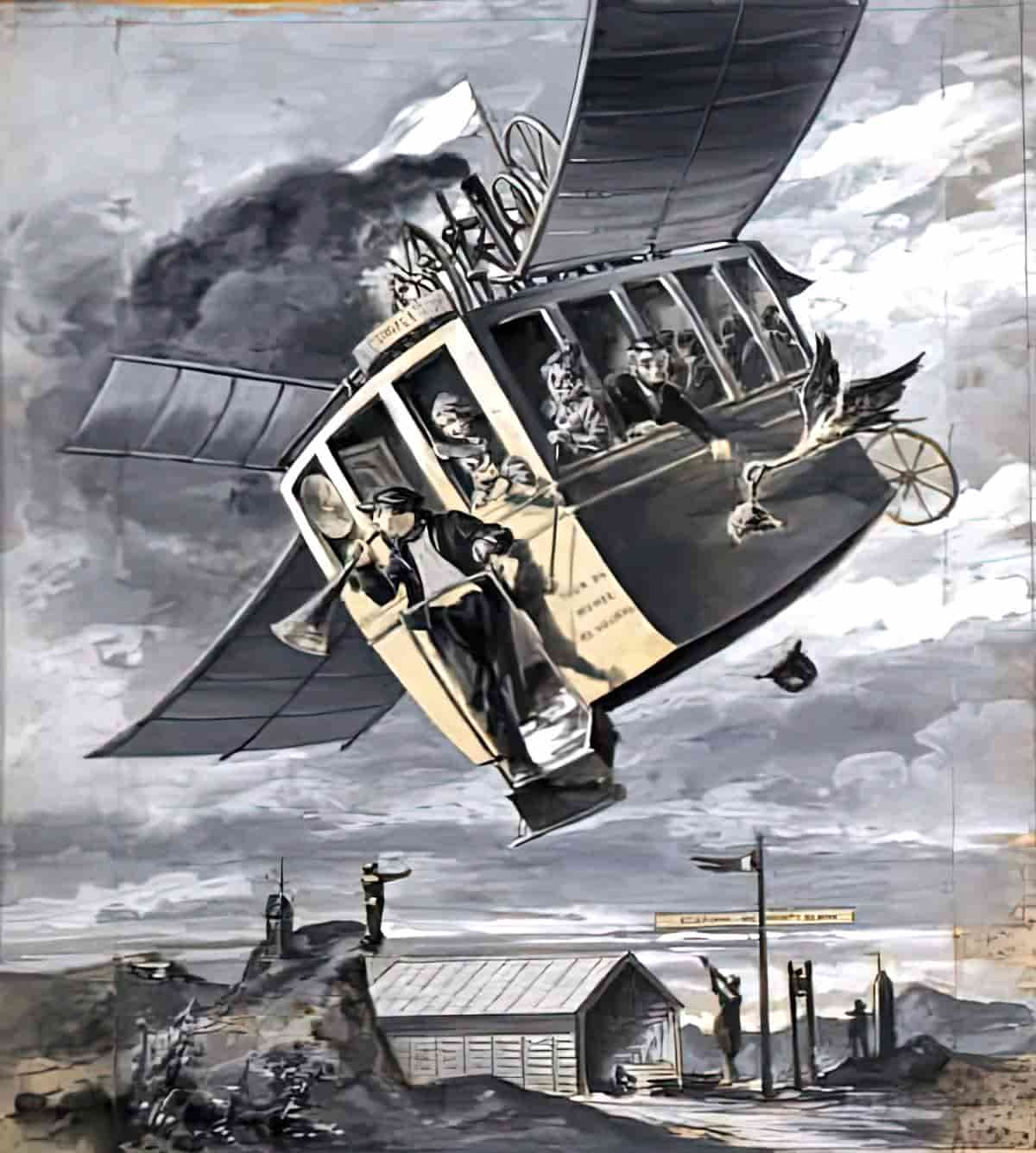

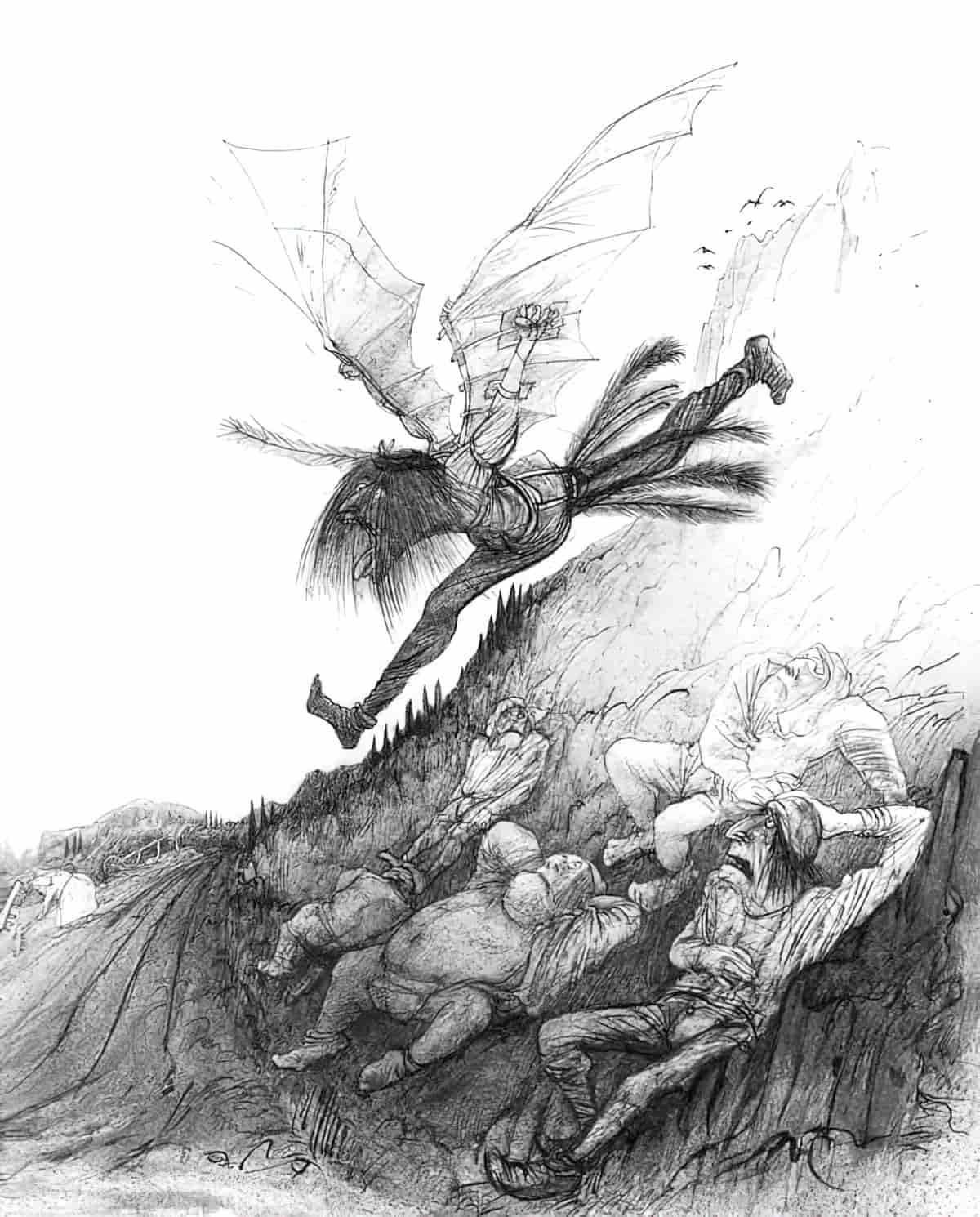

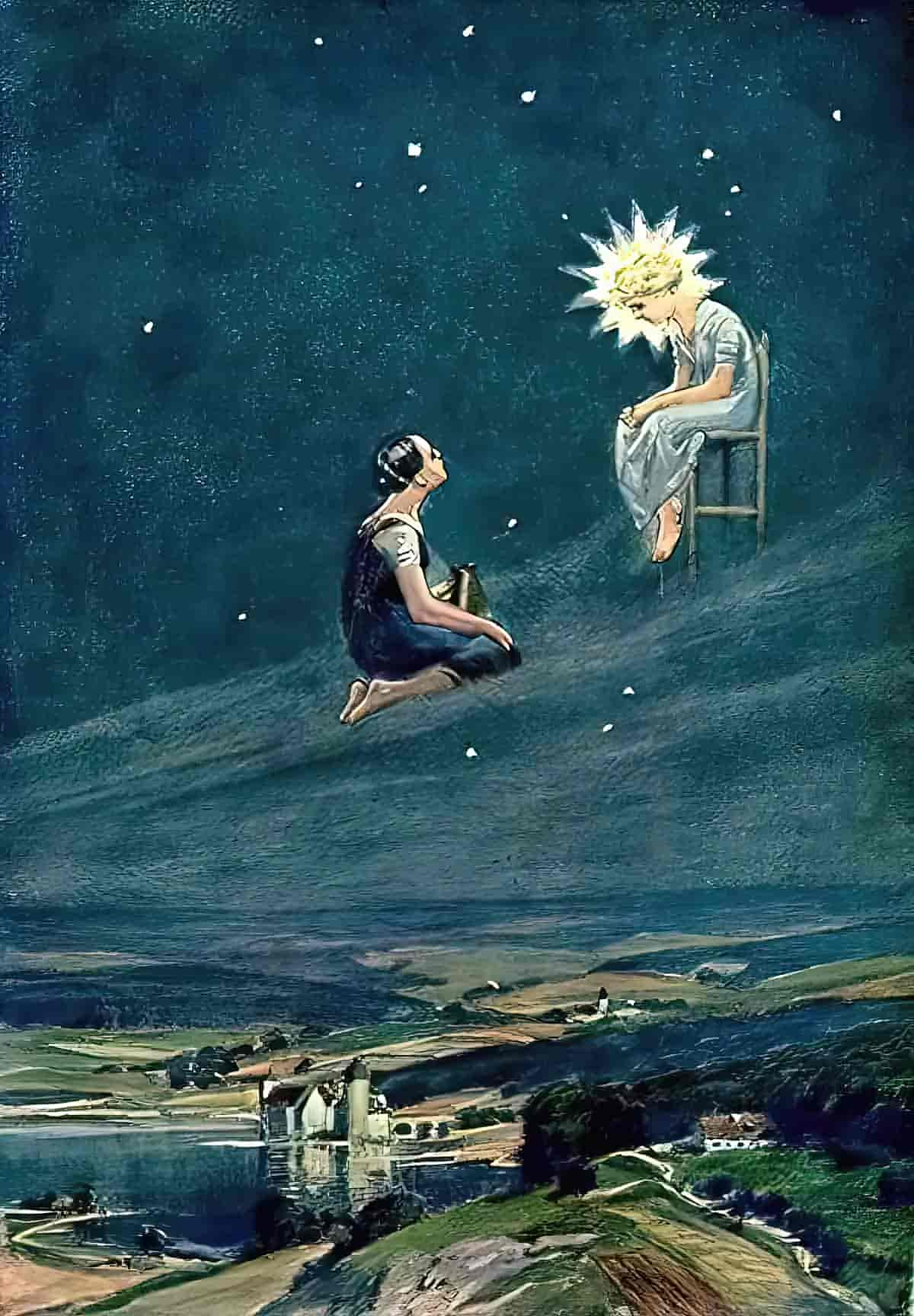

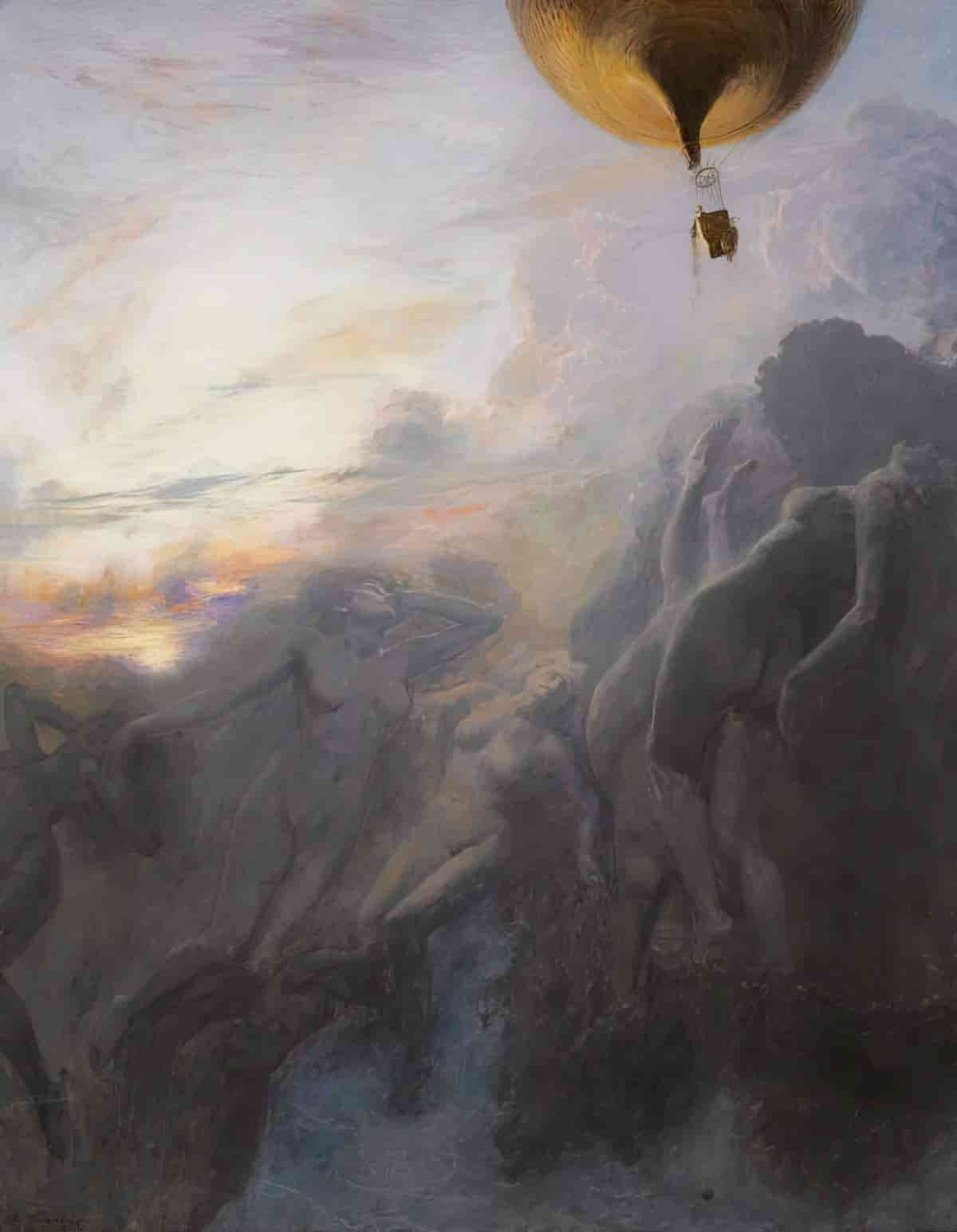

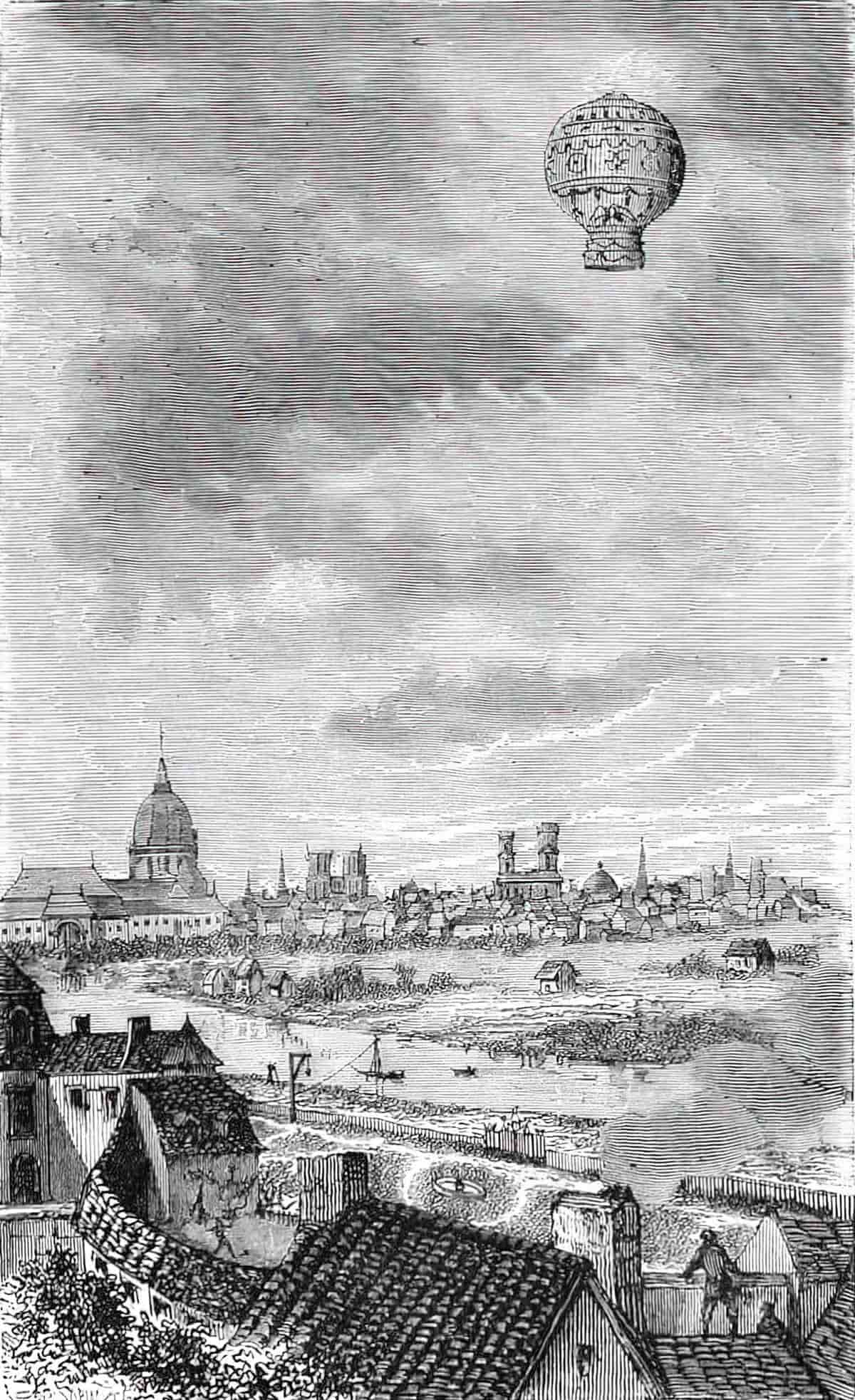

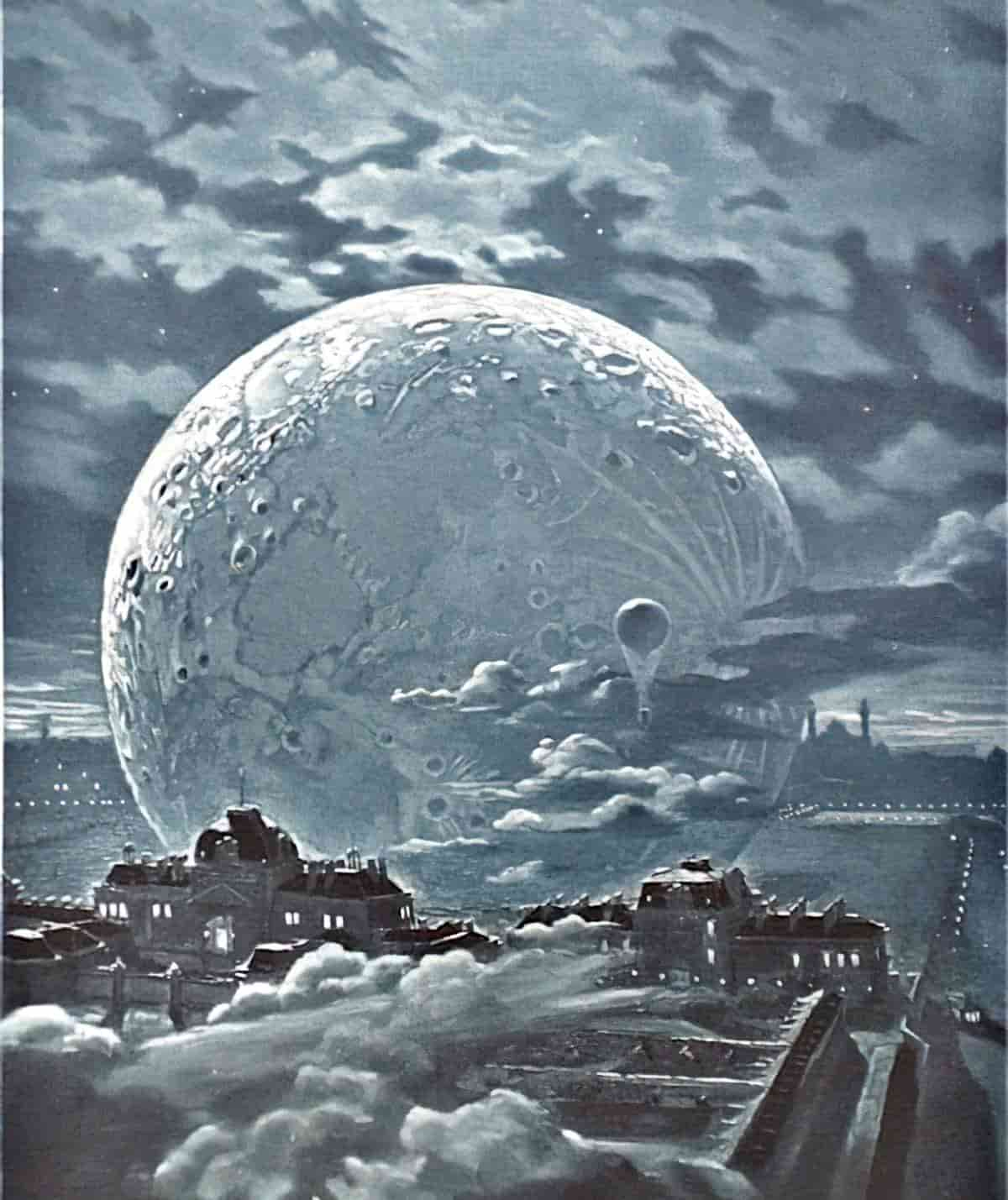

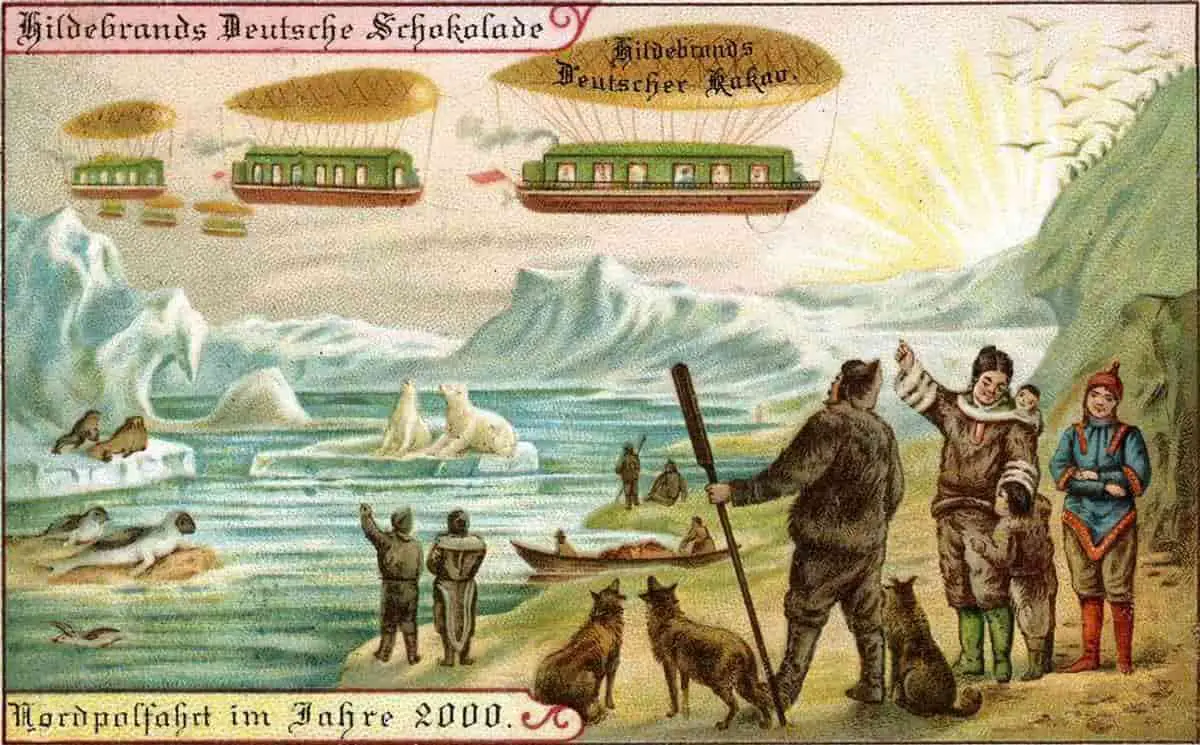

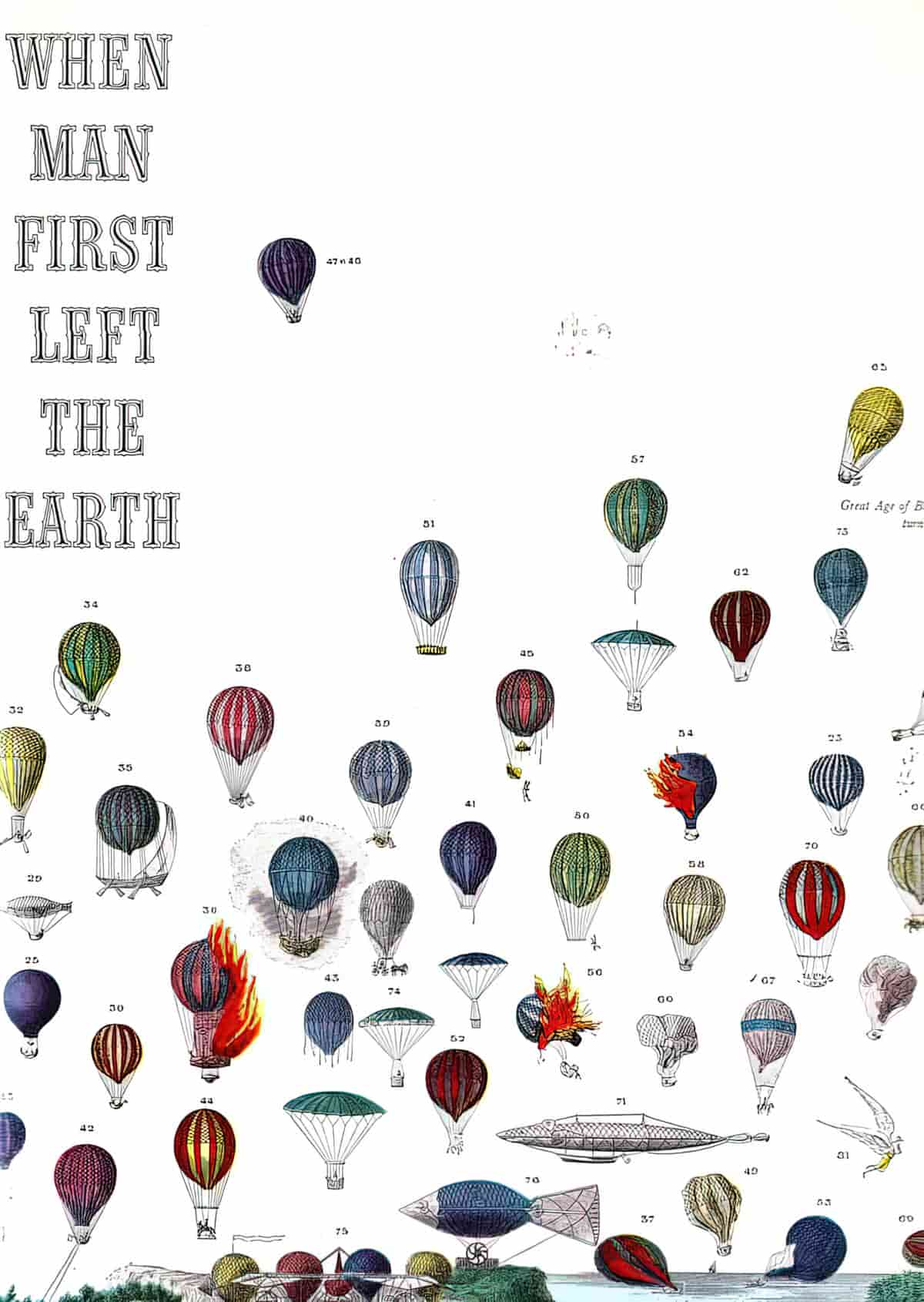

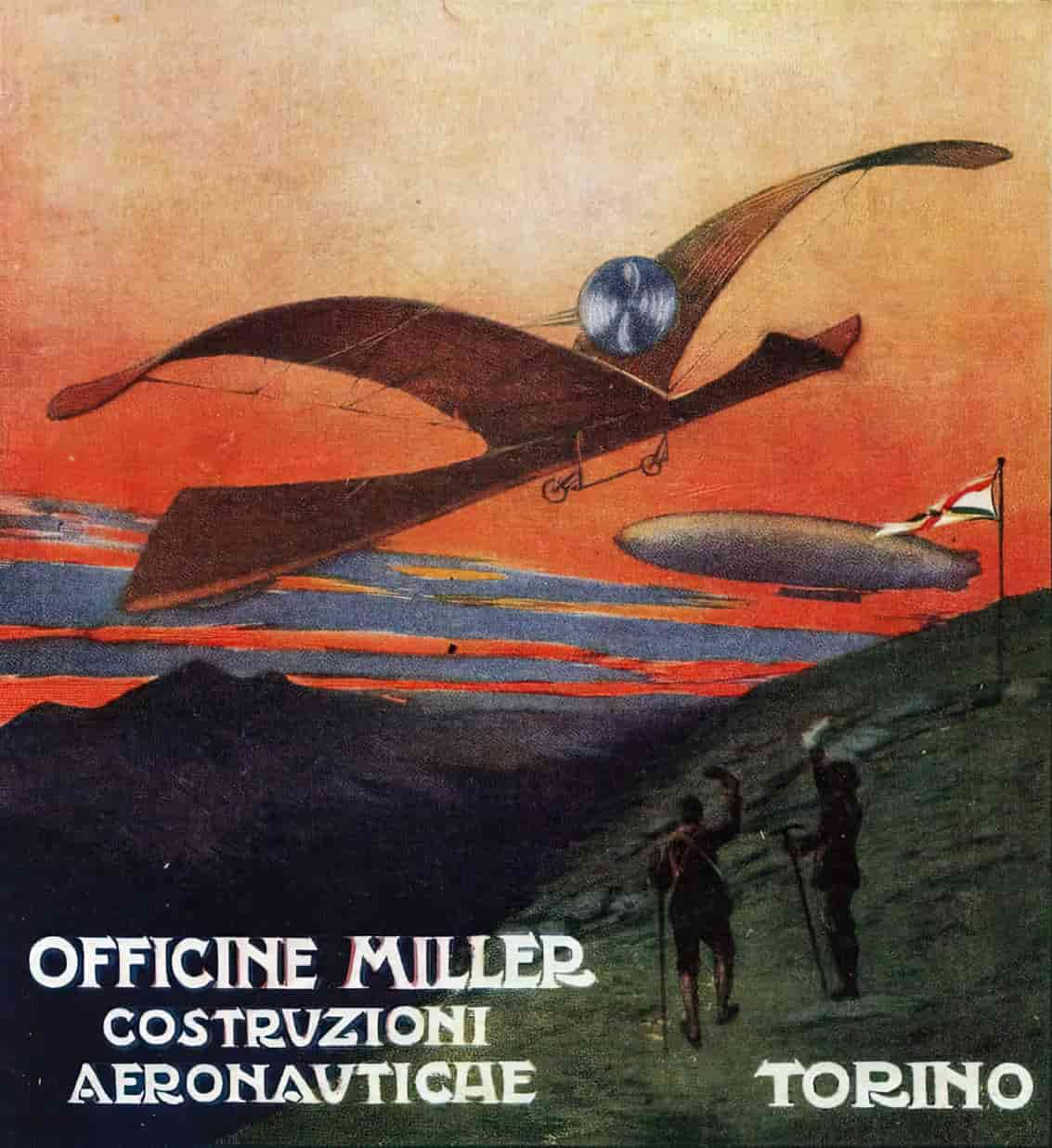

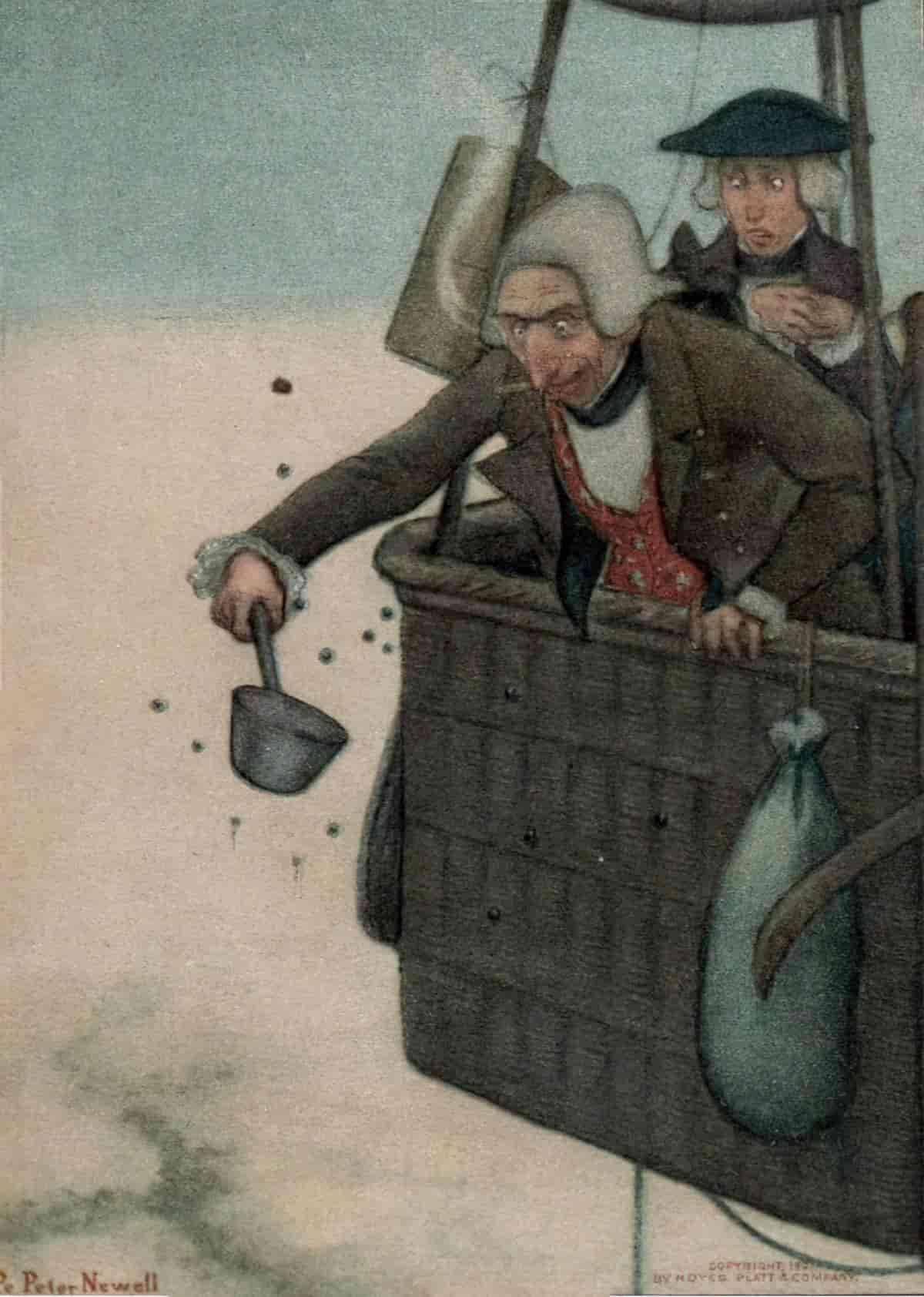

HOW ARTISTS DEPICTED FLIGHT BEFORE PLANES WERE INVENTED

The Wright Brothers became airborne first, but many others were busy nutting out the problem of how to fly like a bird.

100 years ago, artists depicted the year 2000 in a series of illustrations. It’s perhaps not surprising to see how many of them involve the desire to fly, not in a packed plane, but with personal machines strapped to one’s back and feet.

As humans learned how to fly, the development can be tracked somewhat via children’s literature.

Five Children And It was published in 1902. At this point in history, inventors had been trying to make a flying contraption for some decades, with little success.

Then, in 1903 the Wright Brothers achieved something notable and after that humankind had cracked it: We’ve been using the skies for travelling ever since. But what was it like, living in these times of proto-flight? A lot of people had been killed in their attempts to fly. Adults of 1903 would have — many of them — thought, “Well that’s nice, but no way you’re getting me in the air!” and I’m sure I’d feel the same way if space tourism became an affordable thing for the masses. “That’s nice, but I’ll stick to Earth, thanks!” No wonder children’s literature of this time was all about how flying can get you into trouble… but also out of it. In Five Children and It Nesbit goes out of her way to break the inevitable Christian link between winged children and angels, by pointing out that they’re wearing the wrong sort of clothes.

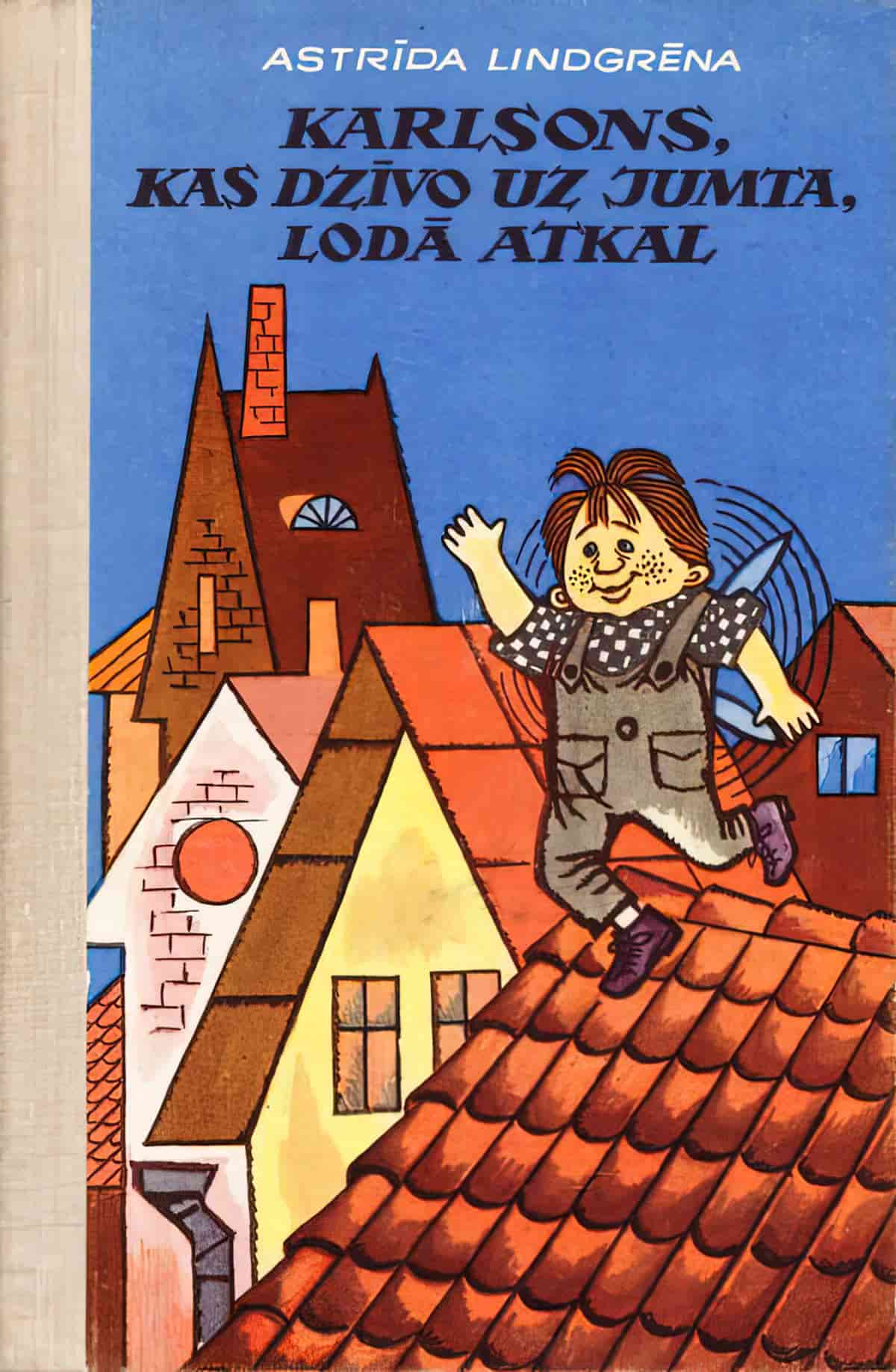

Even after planes and helicopters were invented, the early history of flight-contraptions continued to appear in stories. In Karlsson On The Roof (1955) by Astrid Lindgren, a small man with a propeller on his back appears hovering at Smidge’s window.

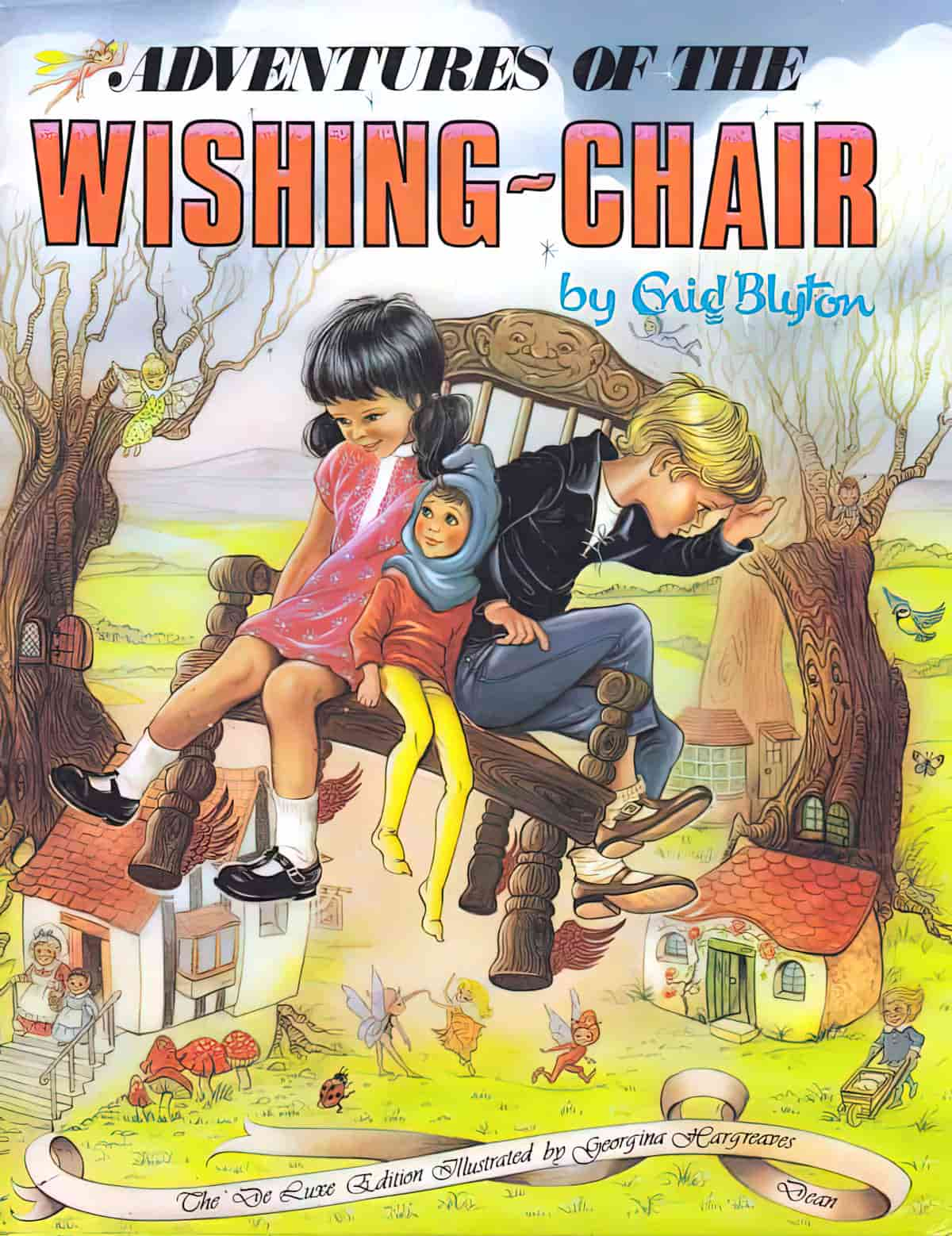

Like the children in Five Children and It or like Enid Blyton’s Molly and Peter from The Wishing Chair books, Smidge and Karlson share all sorts of adventures from tackling thieves and playing tricks to looping the loop and running across the rooftops.

WHAT DOES FLIGHT SYMBOLISE IN LITERATURE?

1. FLYING AS DANGER: ICARUS AND DAEDALUS

All cultures around the world seem to have stories about flying, but one of the most influential stories in Western literature is the Greek story of Icarus and Daedalus.

Thomas C. Foster echoes the idea that flight symbolism doesn’t need to involve actual flying.

There doesn’t have to be any ‘actual’ flying in order for an author to make use of flight symbolism. Simply using the name Daedalus did it in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

2. FLYING AS EUPHORIA

Flying is such a universal desire, utopian settings require flight. It’s difficult to find an example of a utopian setting in literature which does not include flight, even if the flight scenes aren’t the tentpole scenes. Take The Wind In The Willows, for instance:

Toad is on the ‘run’. Flight has its outworking as a chase:

The guard waved his welcome flag, the engine-driver whistled in cheerful response, and the train moved out of the station. As the speed increased, and the Toad could see on either side of him real fields, and trees, and hedges, and cows, and horses, all flying past him, and as he thought how every minute was bringing him nearer to Toad Hall, and sympathetic friends, and money to chink in his pocket, and a soft bed to sleep in, and good things to eat, and praise and admiration at the recital of his adventures and his surpassing cleverness, he began to skip up and down and shout and sing snatches of song, to the great astonishment of the engine-driver, who had come across washerwomen before, at long intervals, but never one at all like this.

The Wind In the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

Eventually Toad takes ‘a flying leap’ and disguises himself as a washer-woman:

Toad was fairly cornered. He looked for escape this way and that, saw that he was too far from the bank for a flying leap, and sullenly resigned himself to his fate. “If it comes to that,” he thought in desperation, “I suppose any fool can wash!”

The Wind In the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

Swallows speak of flying to the Water Rat. We vicariously enjoy flying with them. This is all a metaphor for finding the freedom to be yourself, going where the wind takes you:

“No, you don’t understand, naturally,” said the second swallow. “First, we feel it stirring within us, a sweet unrest; then back come the recollections one by one, like homing pigeons. They flutter through our dreams at night, they fly with us in our wheelings and circlings by day. We hunger to inquire of each other, to compare notes and assure ourselves that it was all really true, as one by one the scents and sounds and names of long-forgotten places come gradually back and beckon to us.”

The Wind In the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

The ability to fly is a common form of wish fulfilment both in adult and in children’s literature, and is seen in the idiomatic expression ‘flights of fancy’:

Flights of fancy allow us, as readers, to take off, to let our imaginations take flight. We can sail off with characters, freed of the limitations of our tuition payments and mortgage rates; we can soar into interpretation and speculation.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

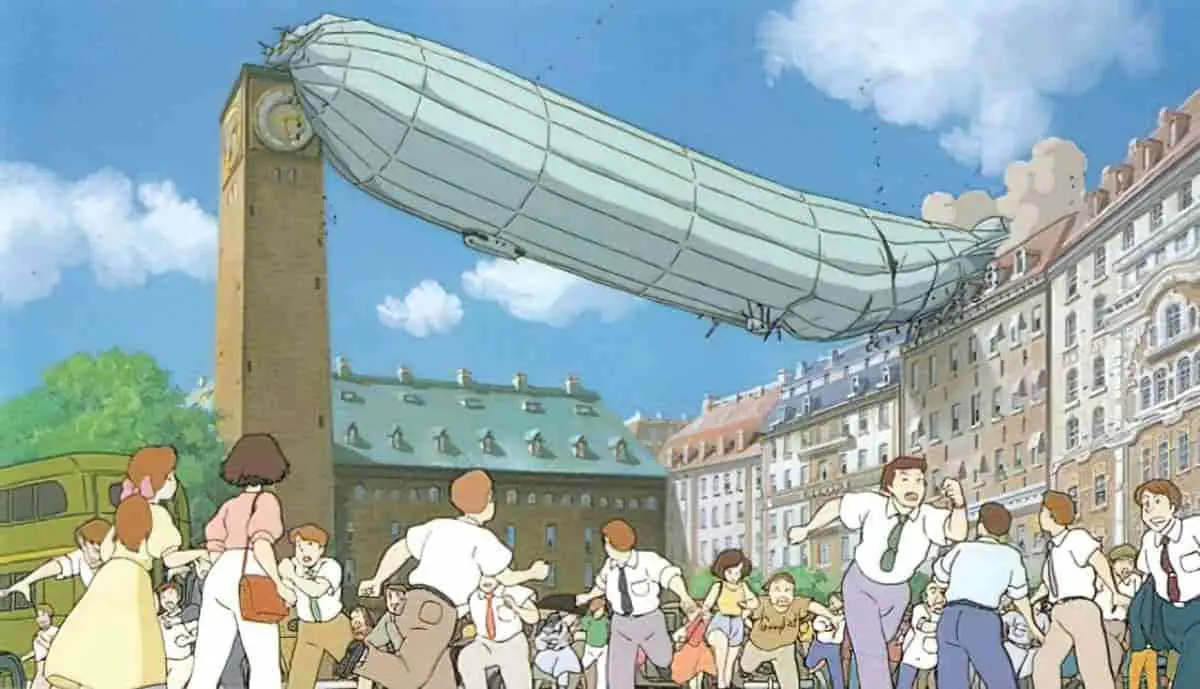

Hayao Miyazaki of Studio Ghibli is well-known for his love of flight in his animated feature films. Look for all the different types of flight symbolism in his work, from actual planes to the cat bus of My Neighbour Totoro, to the various means of flight in his European-esque worlds of films such as Castle In The Sky. (Steampunk fiction is also frequent home of the dirigible.)

FLIGHT AND E. NESBIT

E. Nesbit’s book Five Children And It explores in serial fashion a variety of common wishes. The first chapter explores the wish to be beautiful, in the second chapter the children become temporarily rich (and learn that gold can’t buy happiness), and since Nesbit has a keen understanding of what people would commonly wish for, should they happen upon their own Psammead, the children soon wish for the ability to fly.

Nesbit also had a good grasp on what flying was for, in children’s literature, and the ideology of most works that have come before. By ‘come before’, I’m pretty sure Nesbit was thinking about the Icarus story when she wrote:

So perhaps the winged children really did do one good thing that day. If so, it was the only one; for really there is nothing like wings for getting you into trouble. But, on the other hand, if you are in trouble, there is nothing like wings for getting you out of it.

Five Children And It

Enid Blyton wasn’t the first to write flying chair fantasy. Granny’s Wonderful Chair (1856) by Frances Browne was another popular story of its time.

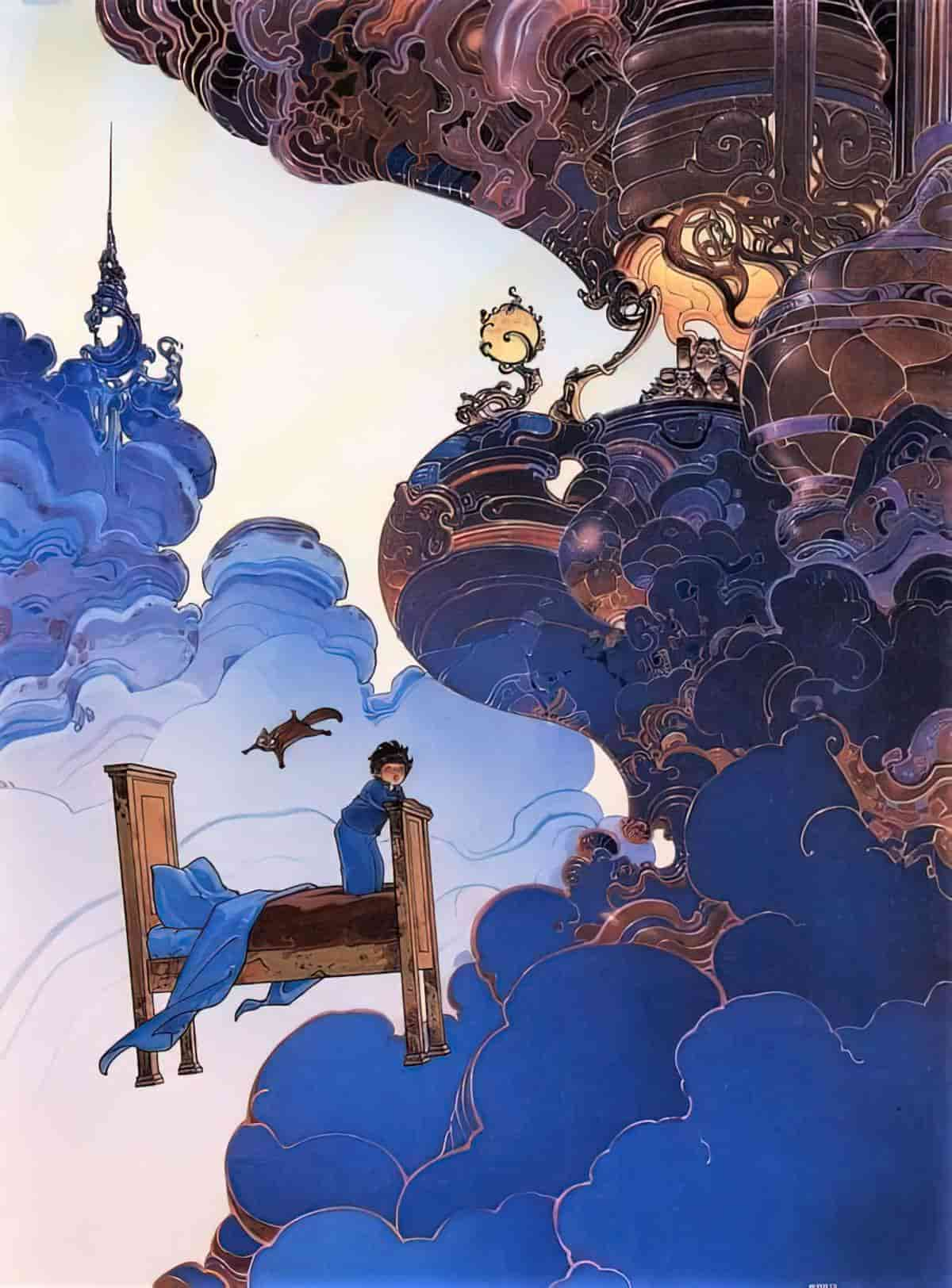

Flying beds are another common motif.

FLIGHT AND ROALD DAHL

Roald Dahl’s five weeks flying in the airforce had a huge influence on him and his writing. Almost every children’s story he wrote featured flying in some form. The leaps and bounds of The BFG, Billy’s flying through flames on a swan in The Minpins, James tethering birds together in James and the Giant Peach, Mrs Twit lifted up by balloons, children being thrown by the Trunchbull in Matilda. His short story collection Over To You is a collection all about flying.

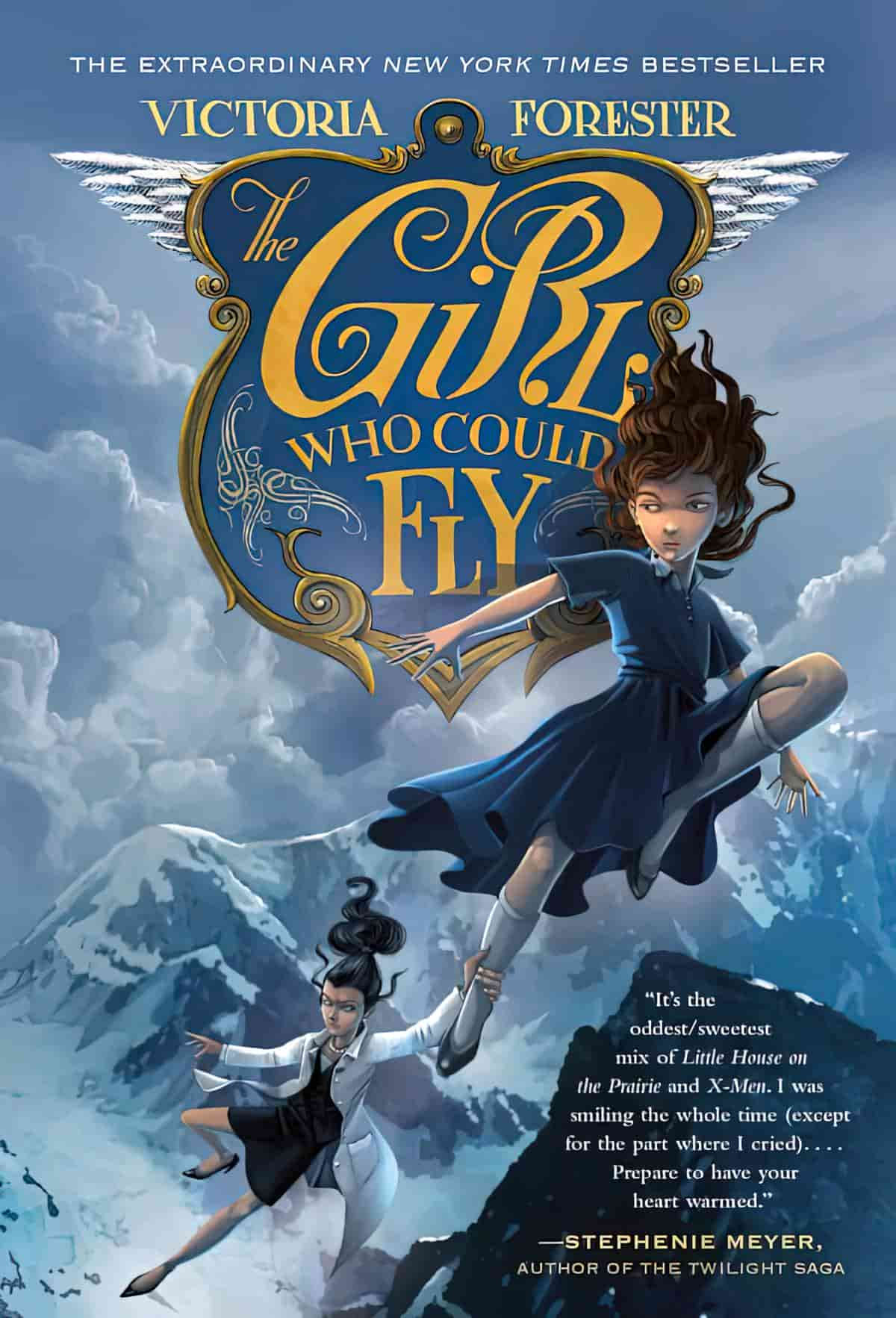

3. FLIGHT AS FREEDOM

Flight as freedom is probably the symbolism we think of first. But don’t stop there. When analysing a text ask: Freedom from what?

A lot of the time, flying equals freedom. Not just freedom from specific circumstances in the plot but also freedom from more general burdens. In a slightly religious sense, flying = freeing of the spirit. The notion that the disembodied soul is capable of flight is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition and probably many others. But for the ancient Greeks and Romans this concept was problematic: the souls of blessed and damned alike were meant to go to an underground realm. The belief in a celestial heaven leads much of later Western culture, who think of a soul as light and travelling upwards.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

Also, does flying really equal freedom? The answer is a little more complicated.

But as in all symbols, the ability to fly can also be symbolic of ‘failure to fly’, or failure to take advantage of one’s freedom.

If anyone flies or falls for too long, Icarus and his imaginary cousins are probably being invoked.

There are plenty of stories about flying whose flights — like Icarus — are interrupted prematurely. In each case there is an element of rebirth.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

In We Found a Hat by Jon Klassen, two tortoises resolve their dispute when they dream of flying away together, both of them wearing the hat they both want. They have been freed from their pull towards the hat. Jon Klassen previously illustrated a similar story written by Mac Barnett, in which the two main characters are propelled through space then land in another world without realising.

In My Father’s A Birdman by David Almond, flight imagery is used as an escape for the grieving, widowed father who is not coping with life, relying on his daughter to be the adult figure.

In Skellig, flying means many things, one of those things being freedom:

[Michael] has an archangel’s name. He has moved to Falconer Road. A falconer is someone who trains winged creatures. Michael helps the winged creature, Skellig. Owls join in the care of Skellig. Michael’s friend Mina (Myna, bird) chants Blake’s verses about a caged bird and observes and draws birds. Birds represent freedom, flight, the soaring spirit. To attain its freedom, a bird must leave the nest (the old house) and find its place in the world (the new house). It is time for Michael to exit the golden cage of childhood and soar up into the terrifying and beautiful world of maturity. It is time for innocent children (Michael and Mina) to resuscitate a winged creature that has given up hope.

The Literary Link

For more on flight as freedom, see The Freedom Of Flight (in film) from Now You See It.

The Steven Spielberg film E.T. features an alien flying on a bike as its main image. The characters in E.T. show hostility to anything new. This is a xenophobic town. When our main character and the poor alien are about to get caught by all the people chasing after them, the bicycle leaves the earth and with it the earthbound grownups. Flying is freedom from smalltown life and its many social restrictions.

FLYING… OR FALLING?

It’s not just flying that’s symbolic: with any flying comes the fear of falling. So what does it mean when a character falls? If a character plummets but still survives this is seen as a feat in its own right. Falling as an act is as symbolic as flying itself.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

In his picture book After The Fall, Dan Santat makes use of fear of falling when he revisits the nursery rhyme of Humpty Dumpty.

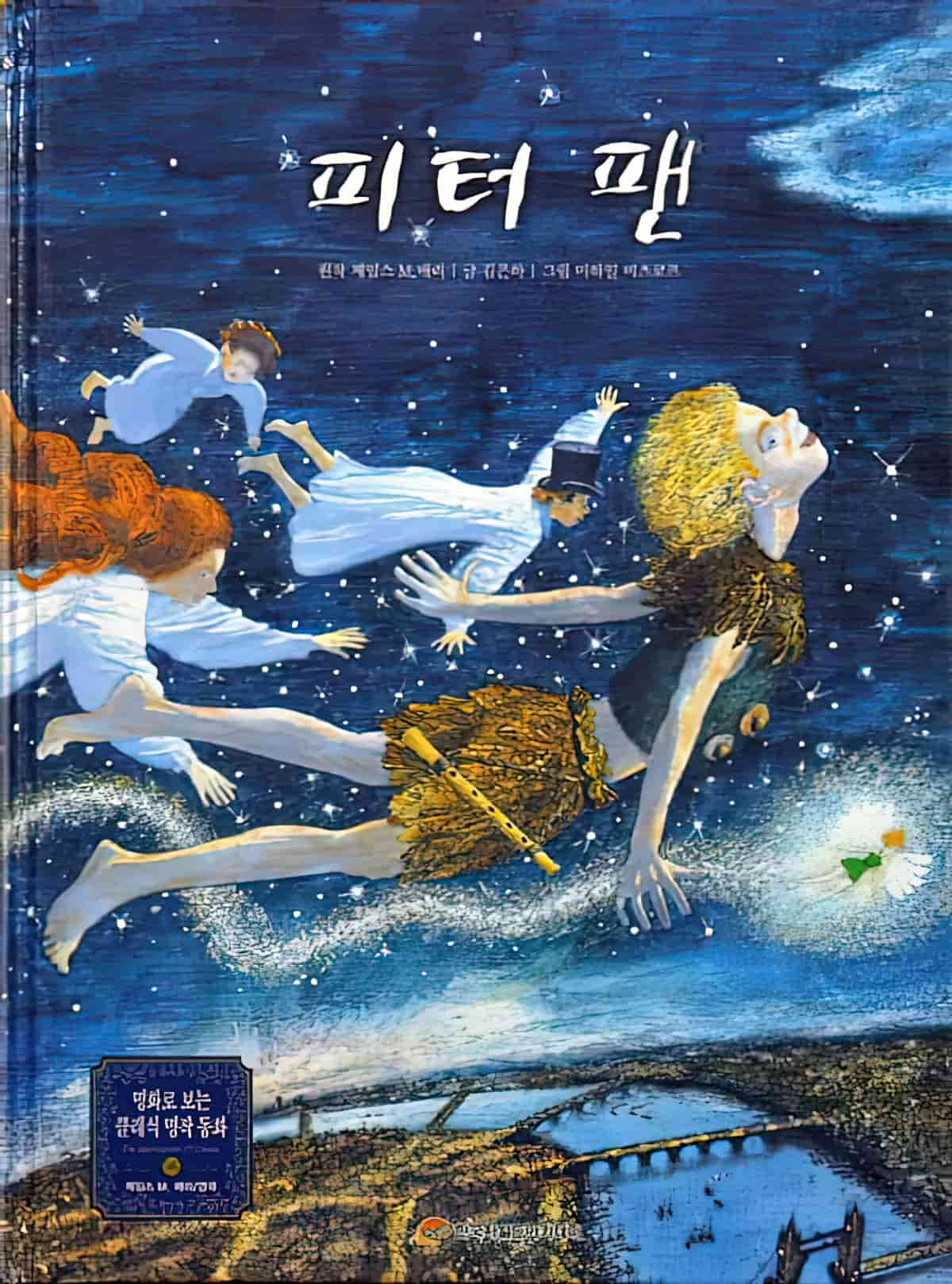

FLYING AND FREEDOM IN PETER (PAN) AND WENDY

Childhood is a time of constraints which frustrate even the happiest children and the flying Peter (of Peter Pan) is an emblem of freedom and autonomy. But more powerfully symbolic is the fact that he teaches the Darling children to fly, for they are surrounded by the kind of restrictions and impediments that children recognise — rules about bedtime, medicine, pyjamas, baths, night lights — so it seems that if they can fly then any child can break free. Their departure through the nursery window , ‘like a flight of birds’ is an exhilarating image of escape from the mundane. In liberating the children from the boring routine of school and office which Mr Darling represents, Peter, like Jack in ‘Jack And The Beanstalk‘, overcomes the giant, the oppression of public authority.

Deconstructing The Hero, Marjery Hourihan

FLYING EQUALS SEXUAL AUTONOMY

This idea is perhaps more common in young adult literature than in middle grade. The film Maleficent offers a good example:

I had wings once, but they were stolen from me.

Maleficent, the retelling of Sleeping Beauty with the evil fairy as the viewpoint character

CAGES

Look, too, for cage symbolism which is tangentially related to freedom and also, specifically, to flight (since cages tend to cage birds).

At one level, CHILDREN ARE BIRDS and SCHOOLS ARE CAGES operate as fairly traditional (and obvious) symbolism.

Roberta Trites, in a discussion of David Almond’s My Name Is Mina and Skellig, Literary Conceptualizations of Growth: Metaphors and cognition in adolescent literature

4. FLYING AS CLOSER TO GOD

We know that for the Ancient Greeks, the blessed and damned alike were headed for the underworld. The belief in a celestial heaven leads came later to Western culture. Heaven equals Sky, a Christian notion, but Jewish people came up with it.

“They say that shoulder blades are where your wings were, when you were an angel [Mum] said. “They say they’re where your wings will grow again one day.”

Skellig, David Almond

“It’s just a story, though,” I said. “A fairy tale for little kids, isn’t it?”

“Who knows? But maybe one day we all had wings and one day we’ll all have wings again.”

“D’you think the baby had wings?”

“Oh, I’m sure that one had wings. Just got to take one look at her. Sometimes I think she’s never quite left Heaven and never quite made it all the way here to Earth.”

This is related to the concept of angels of course, and also to the Victorian concept of the child as completely innocent, clean and pure.

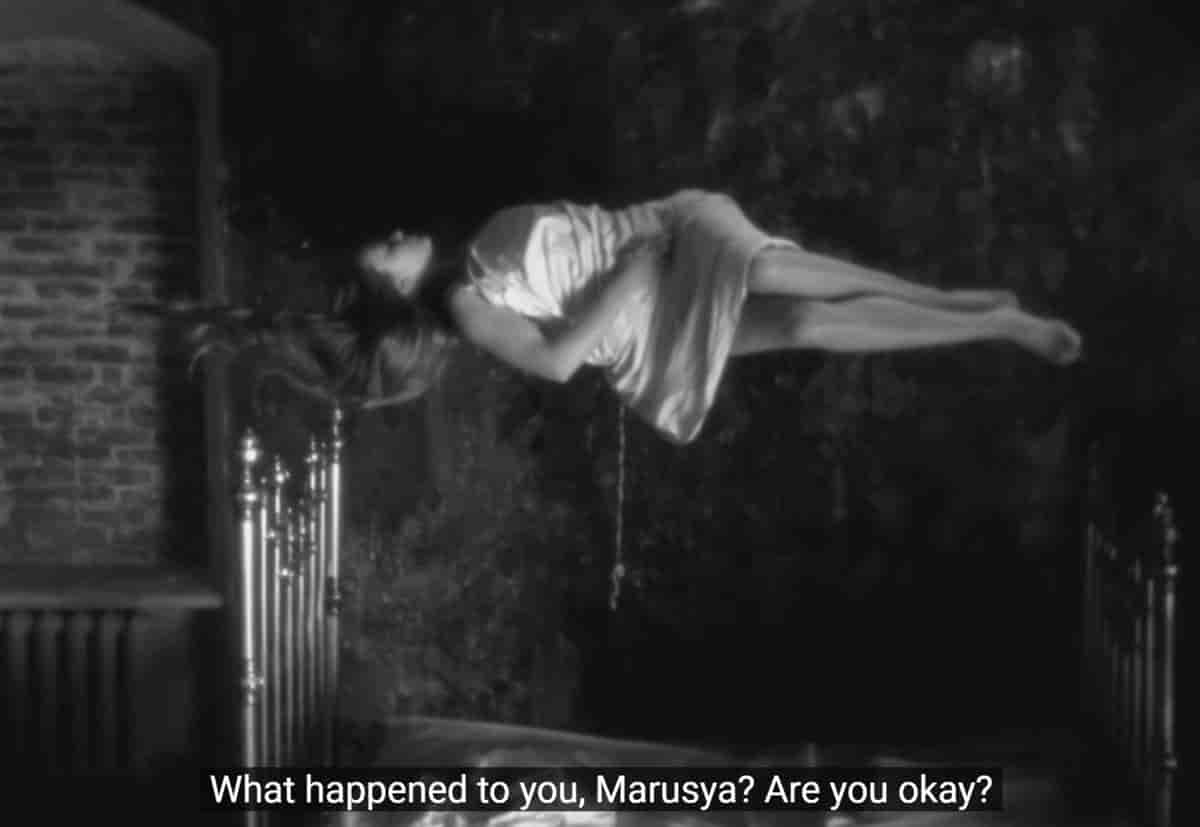

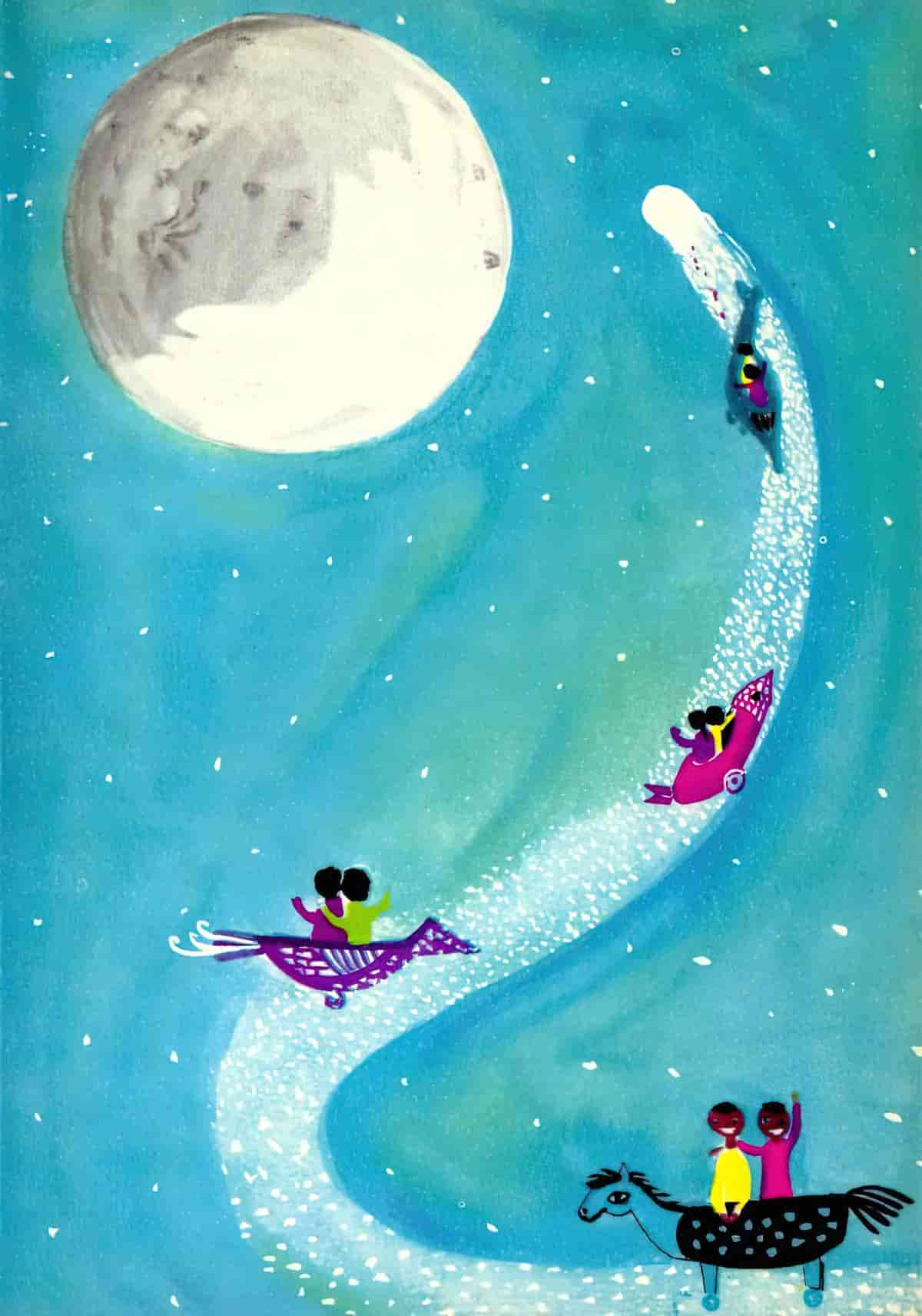

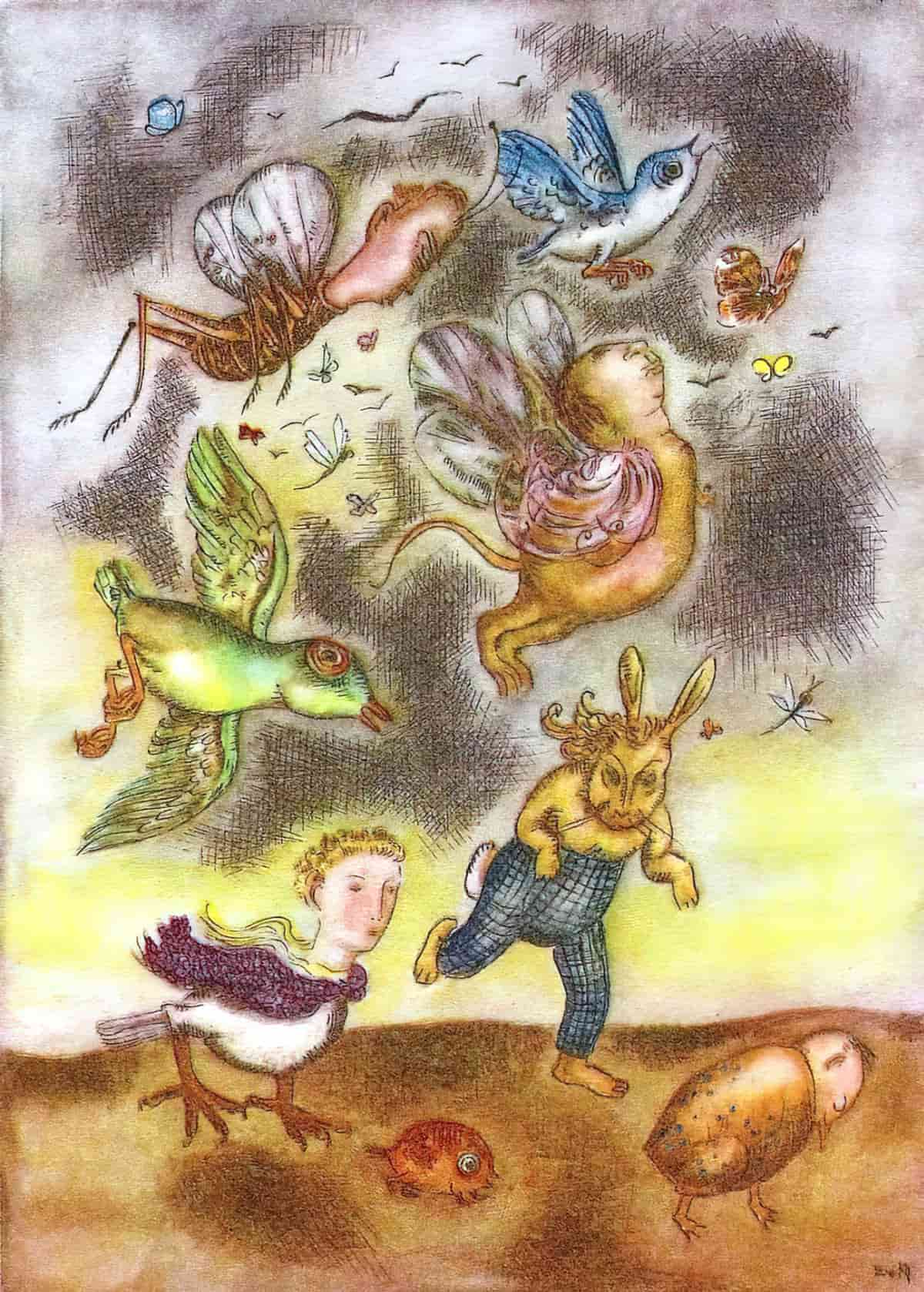

5. FLIGHT AS HALLUCINATION AND DREAM

When a character either starts flying or sees something flying that… shouldn’t be flying, this often indicates some kind of dream, nightmare or hallucination.

This is why flight is so often a part of fantasy.

But how common are dreams about flying?

Not very common at all. According to a German paper called Frequency and nature of flying dreams in a long dream series by Michael Schredl, fewer than 2% of dreams feature unaided flying. But that’s non-lucid dreams. When people engage in lucid dreaming (meaning when you’re conscious during a dream), the nature of flying is different. Lucid flying dreams last longer, mostly about people flying in prone position, and flying hasn’t come about as a result of jumping, running etc, but after careful concentration.

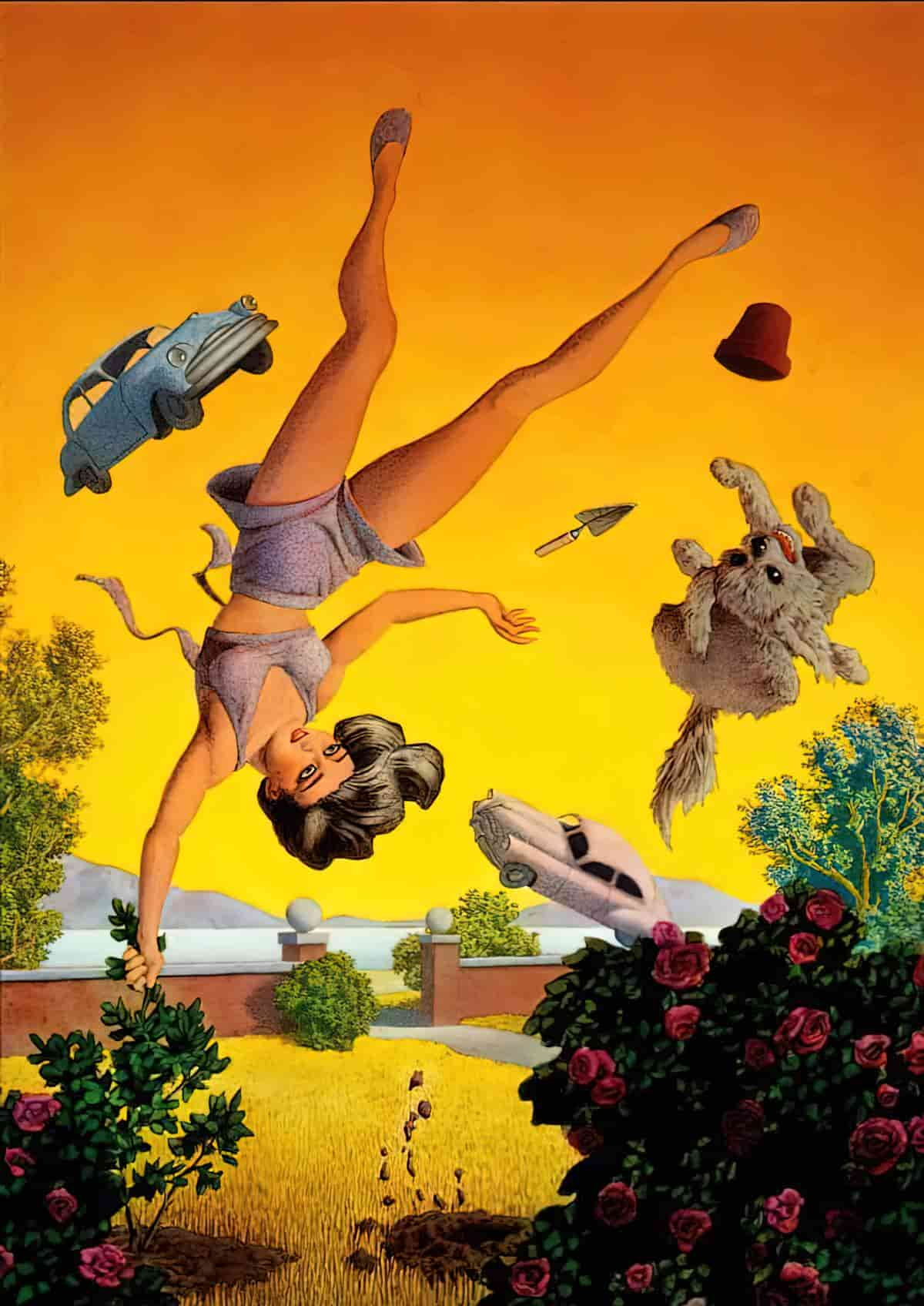

In 20% of the flying dreams, the dreamer was using some apparatus in order to fly (flying cars, buses, a juggling ball). Dreamers also tended to talk about what position their body was in when they were flying (standing upright, prone, etc). Almost half of the flying dreams were fun, but just over 30% of dreamers were afraid of falling from the sky.

Dreams about flying aren’t affected by flying in real life. But the main takeaway from that paper is that further research is needed on flying in dreams.

Examples of flight sequences which may or may not be fantasy, dream or hallucination:

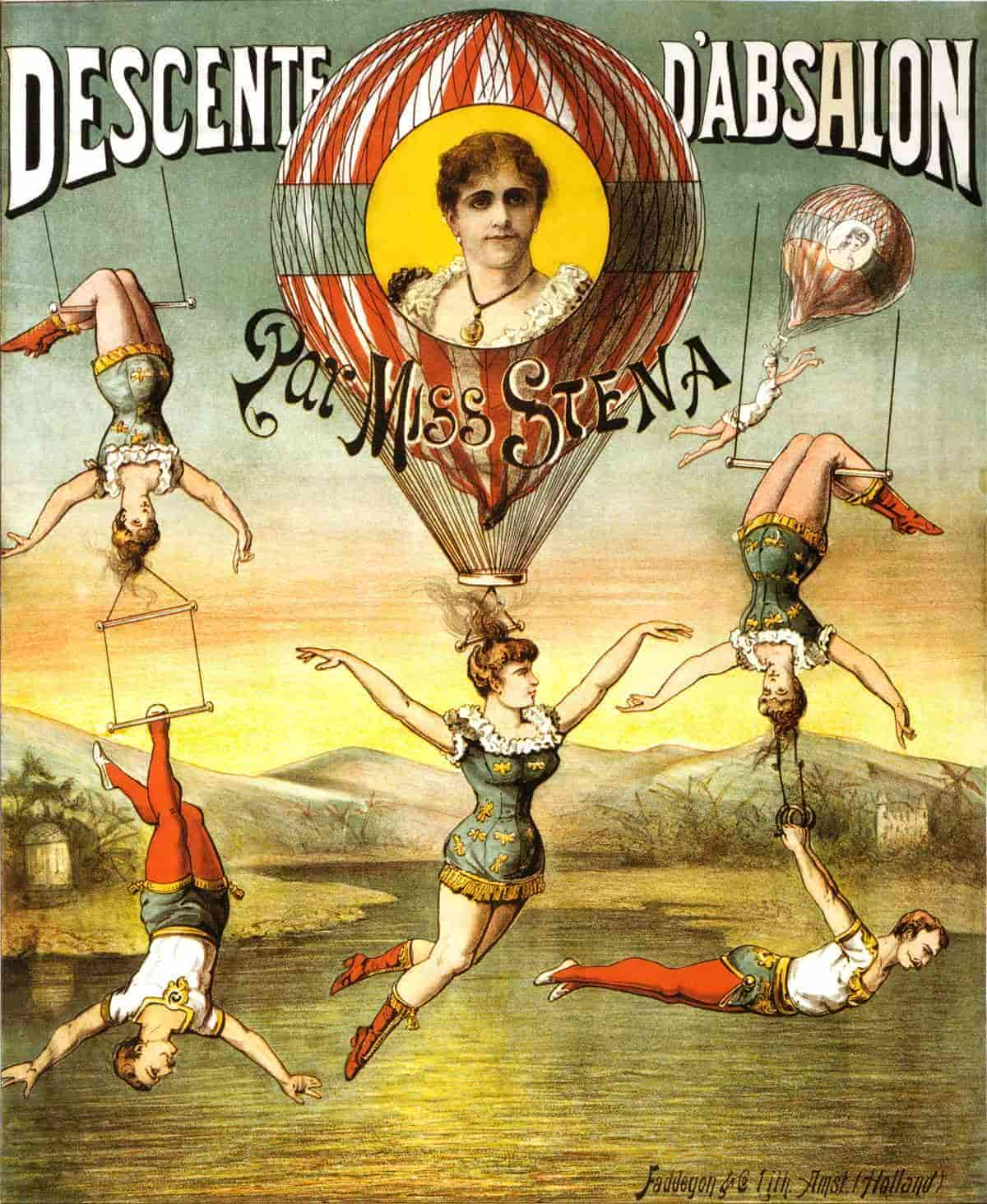

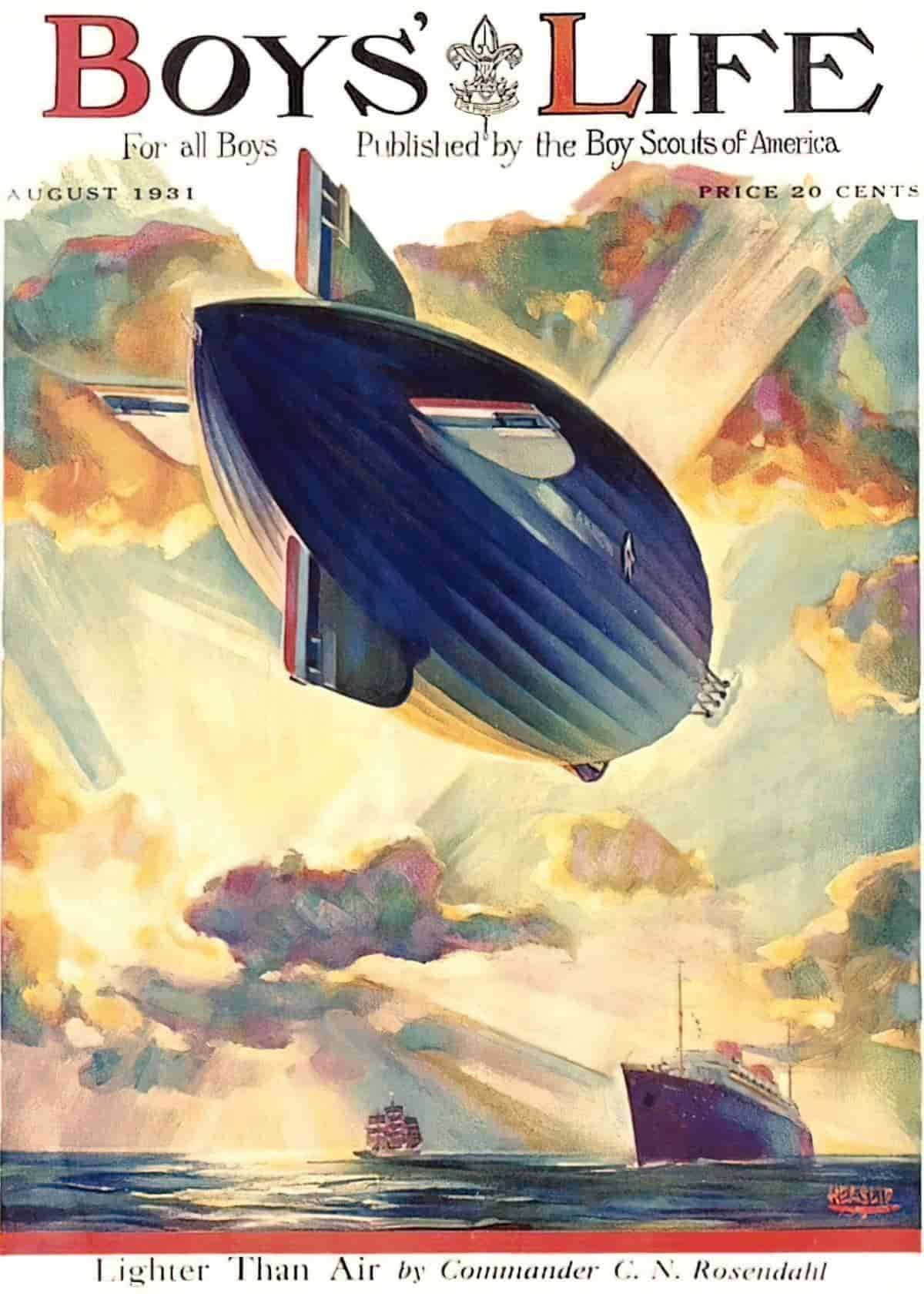

6. FLIGHT AS MASCULINISED WARTIME PROPAGANDA

Flight as a good boy’s fantasy played right into patriotic propaganda and made sure generations of young men were ‘happy’ to be sent off to war for an adventure. These boys had been primed their whole lives by the adventure story, and the idea that proper boys should want to separate from their natal families and explore the world.

For all genders, flight can be a respite from day-to-day drudgery. For centuries, women have fantasised about escaping domestic drudgery using the few tools at their disposal, most notably the broomstick.

Some of Ray Bradbury’s science fiction and fantasy stories involve flight. Bradbury’s flight motifs are frequently a specifically masculine dream fantasy in which a man escapes domestic drudgery:

7. FLIGHT AS DISAPPEARANCE OR LOSING SOMETHING PRECIOUS

Nothing is absolute.

Frida Kahlo

Everything changes,

everything moves,

everything revolves,

everything flies and

goes away.

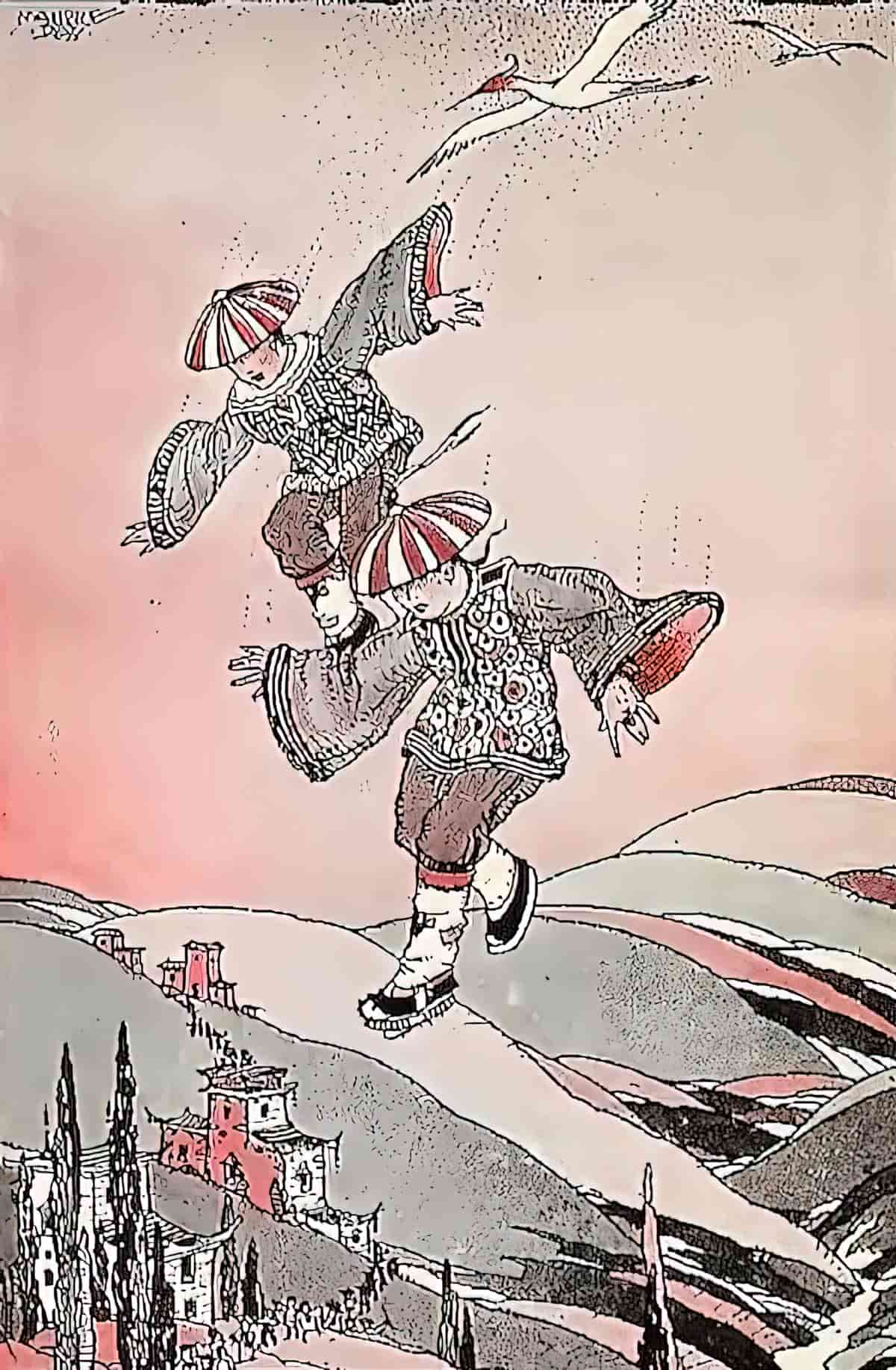

HUMANS FLYING ON THE BACKS OF ANIMALS

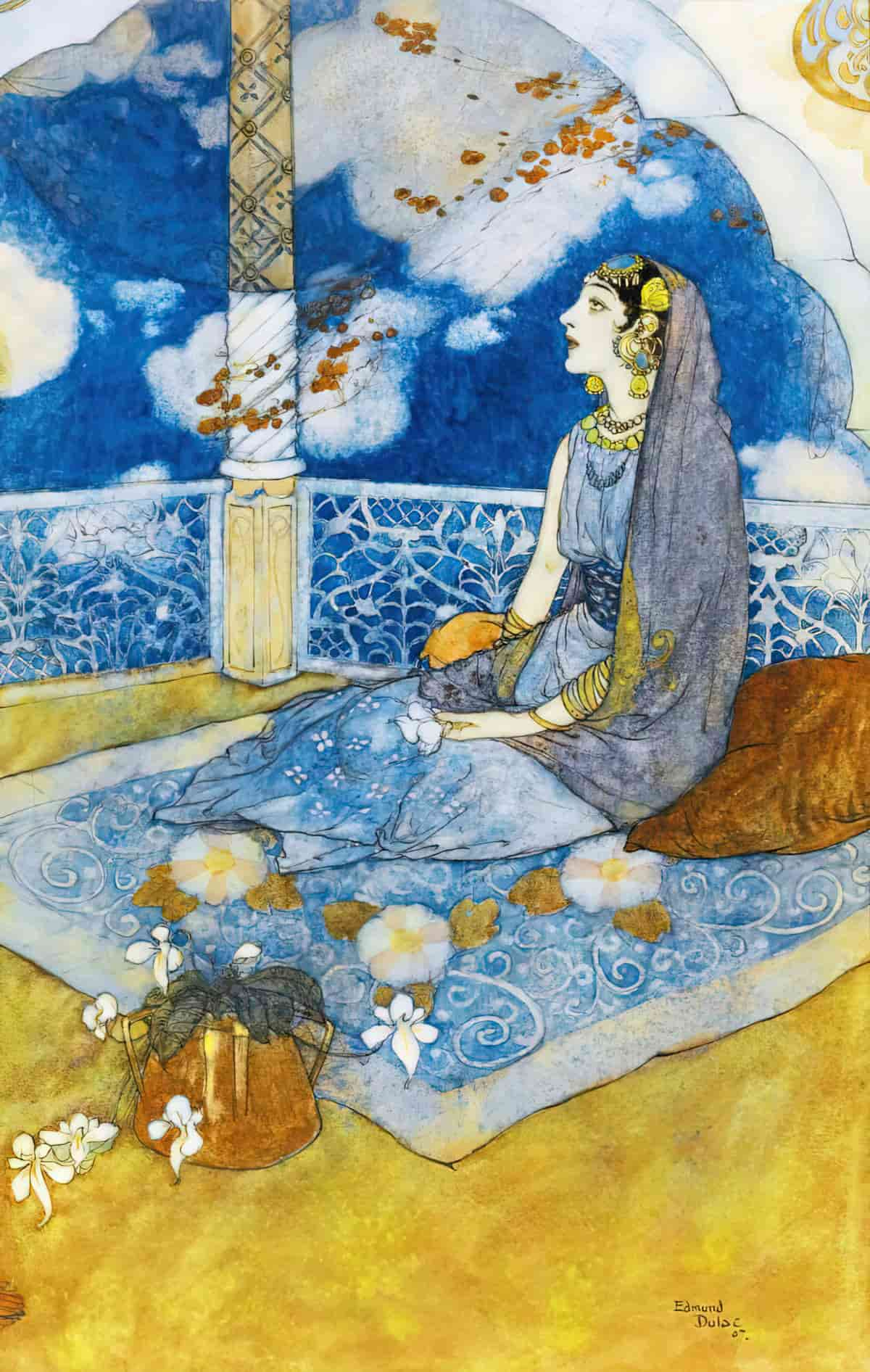

When you take a look at art from the Golden Age of Illustration there are so many examples of humans (or miniaturised humans) riding animals. What’s even more remarkable is that almost every animal you can think of has been depicted with something riding on its back.

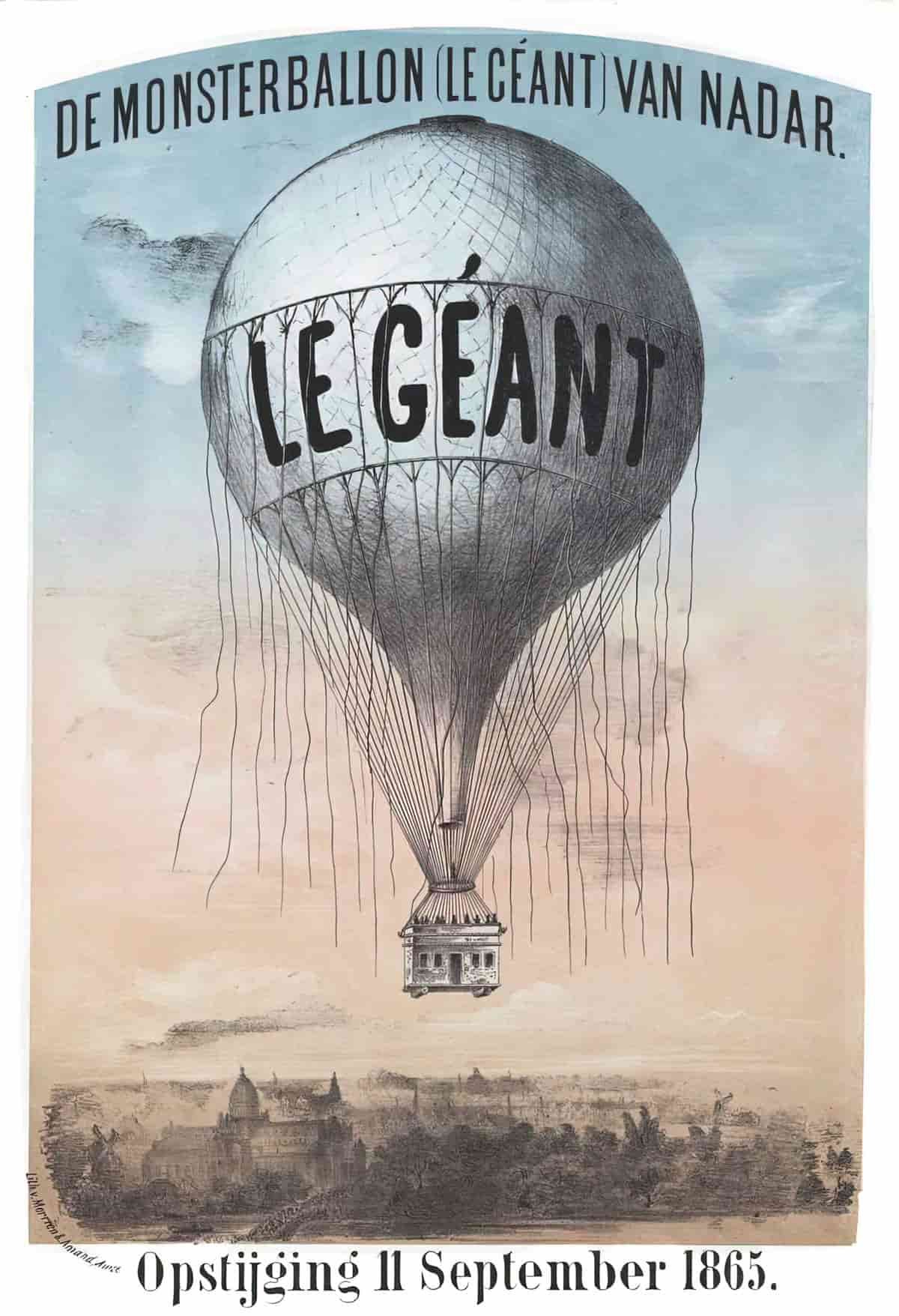

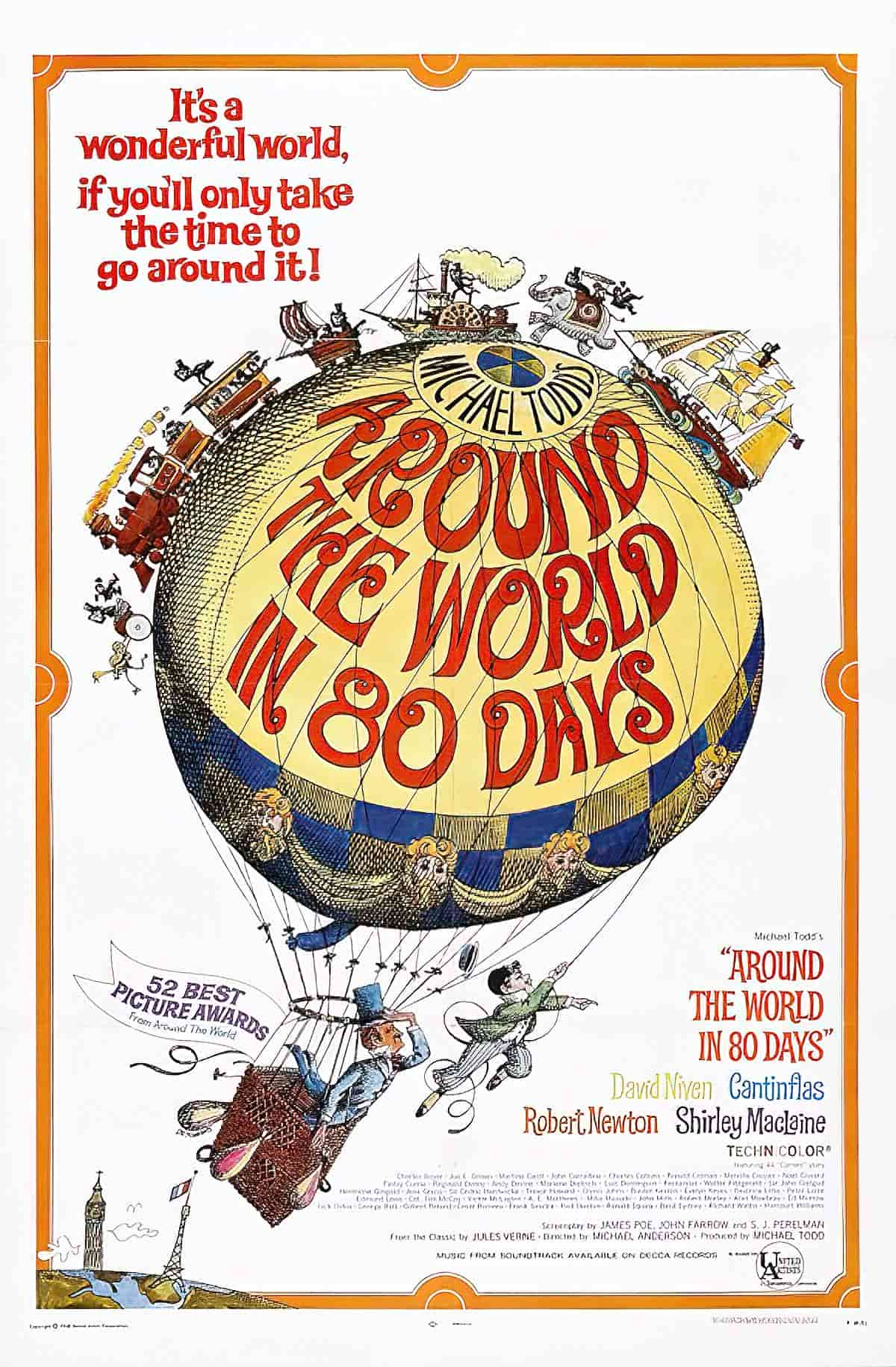

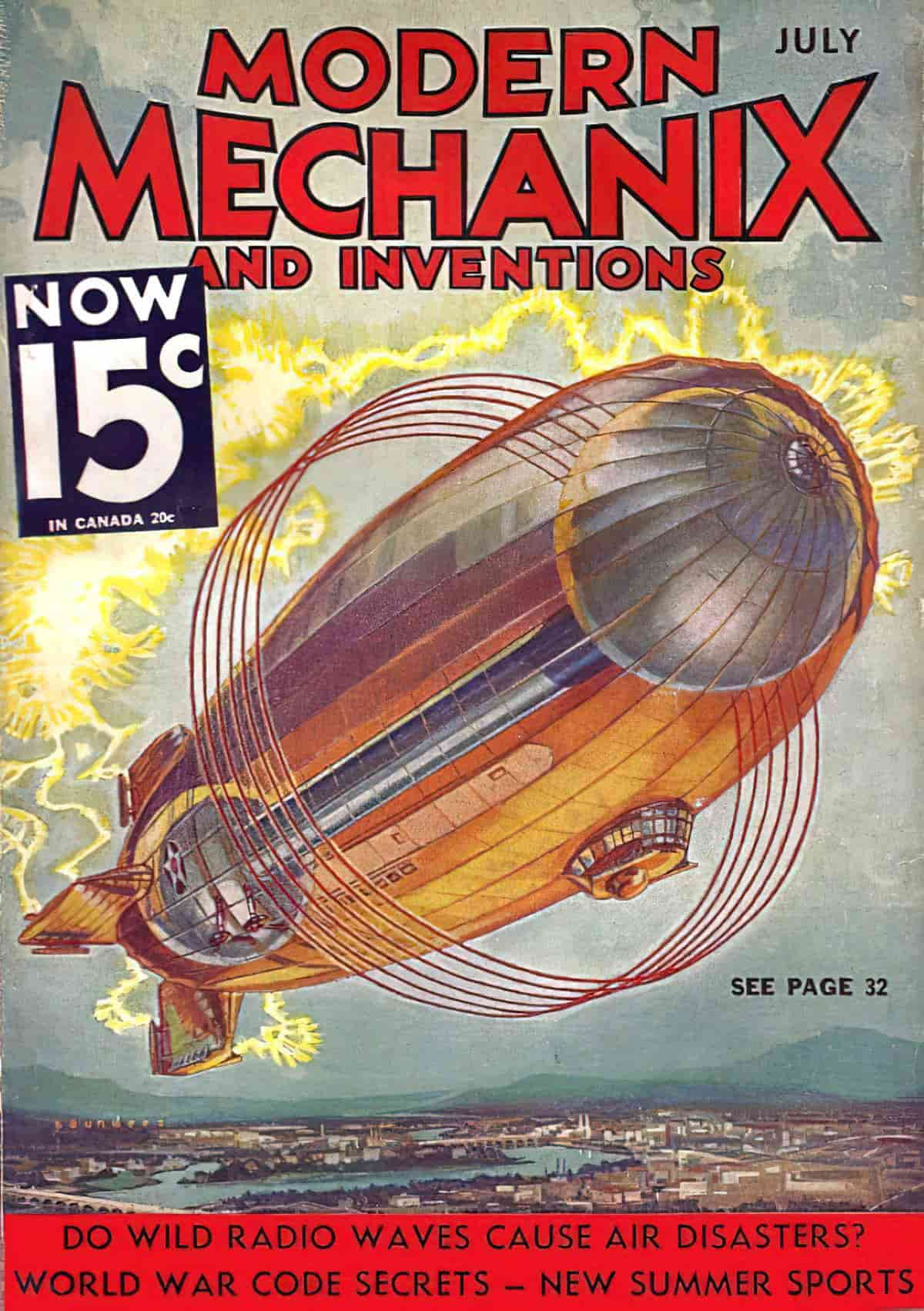

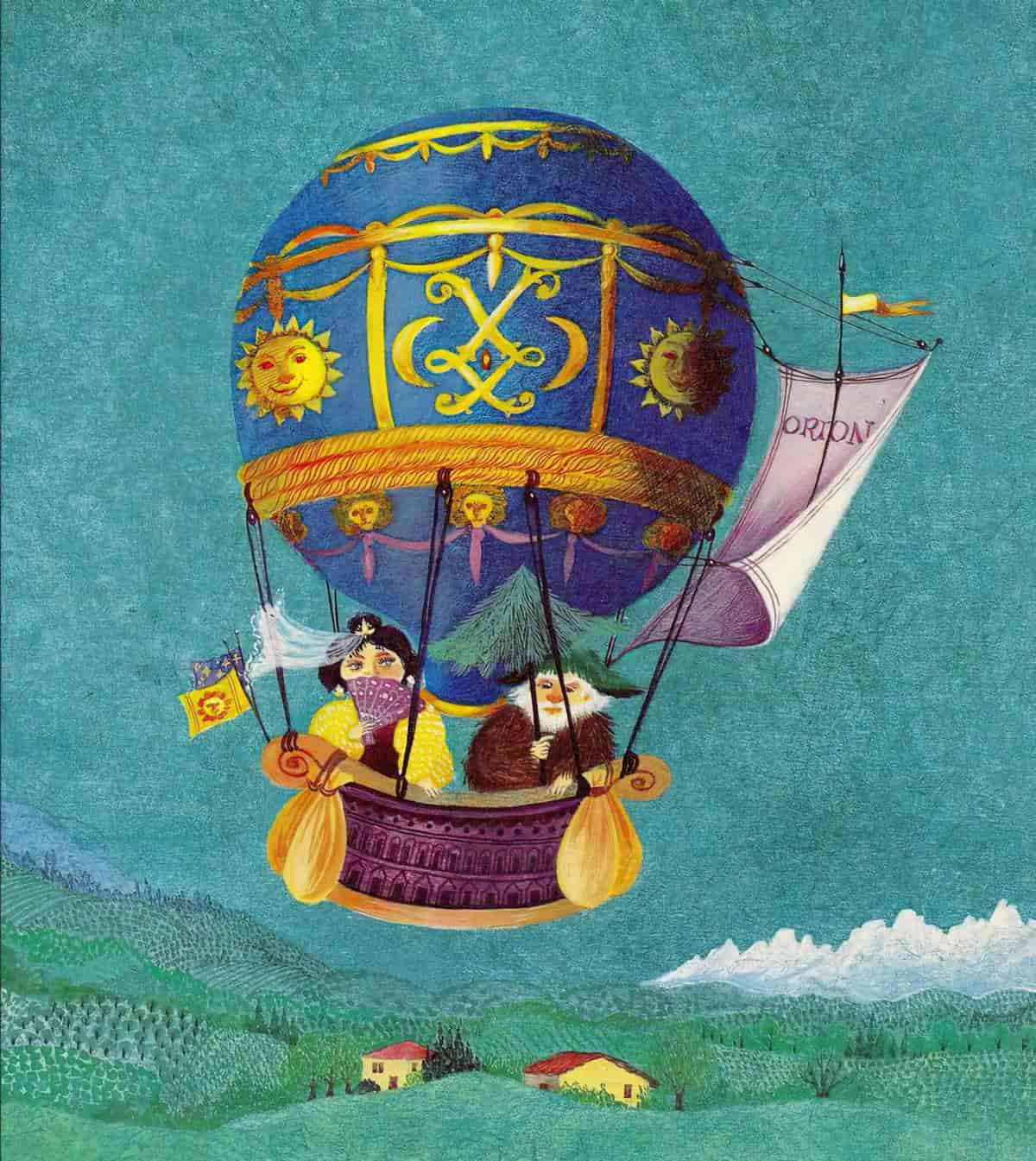

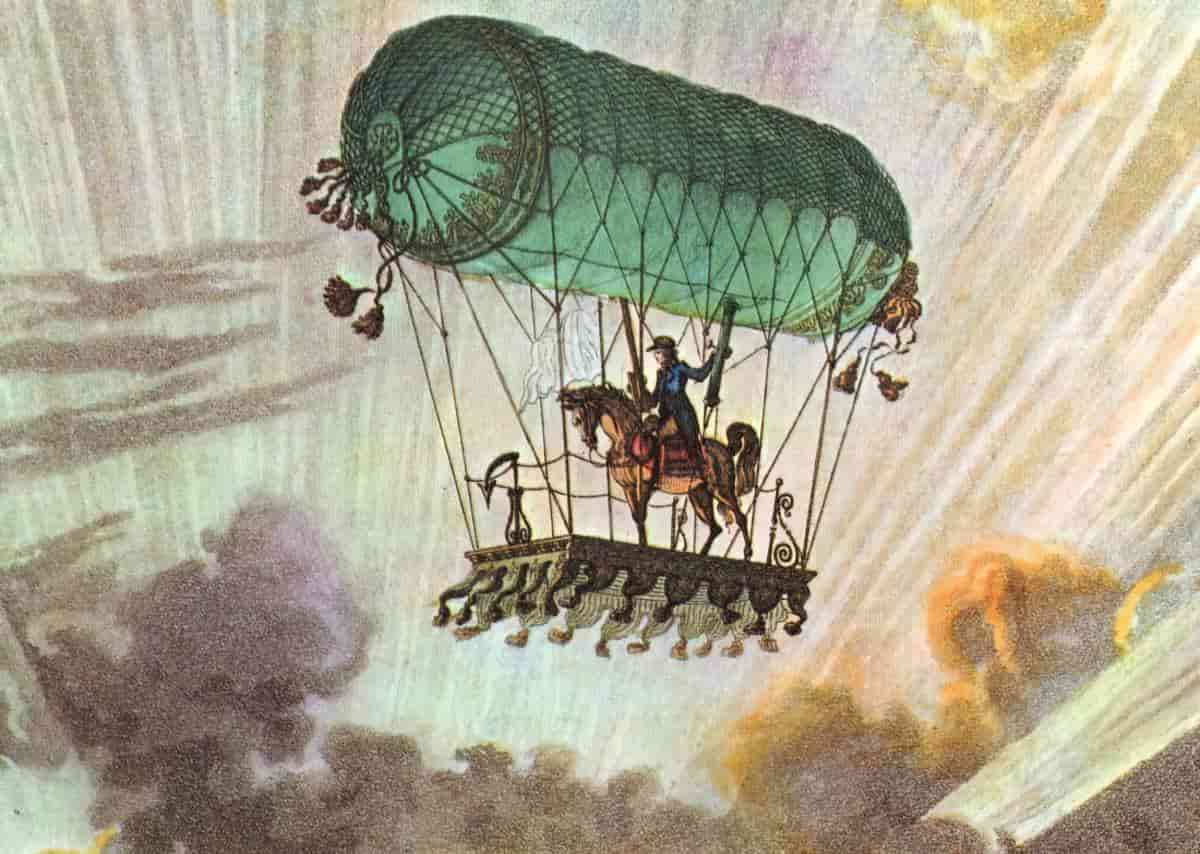

THE AIRSHIP

The airship, dirigible or hot air balloon is another means by which writers can take their characters into the sky, varying the topography and the view. This means of flying has more in common with floating than flying, per se.

The title of the … Disney/Pixar movie “Up,” as well as its signature image of a house floating beneath thousands of tethered balloons, reminds us how frequently the theme of Lightness appears in children’s literature. From Mary Poppins to Peter Pan, from Tarzan swinging on vines to Harry Potter scooting on his broomstick, children’s stories seem to feature the quick, the lithe and the aerial. Maybe that’s not surprising. While adults seem earthbound, youngsters zoom by on skateboards or jump from heights as caped incarnations of Superman.

Jerry Griswold, Literary Antecedents To The Movie Up

Walter Tipple is looking for adventure. He keeps having a dream that his big brother, Tank, appears before him and says, “Let’s you and me go see my world, little man.” But Tank went to the army and never came home, and Walter doesn’t know how to see the world without him.

Then he meets Posey, the brash new girl from next door, and an eccentric man named Banjo, who’s off on a bodacious adventure of his own. What follows is a summer of taking chances, becoming braver, and making friends–and maybe Walter can learn who he wants to be without the brother he always wanted to be like.

Halfway to Harmony is an utterly charming story about change and growing up.

Evie is determined to win first prize at the Strawberry Fair with her amazing hot-air balloon! But on the way to the competition the creatures of Wildberry Acres need her help. What is most important to Evie: winning or helping others?

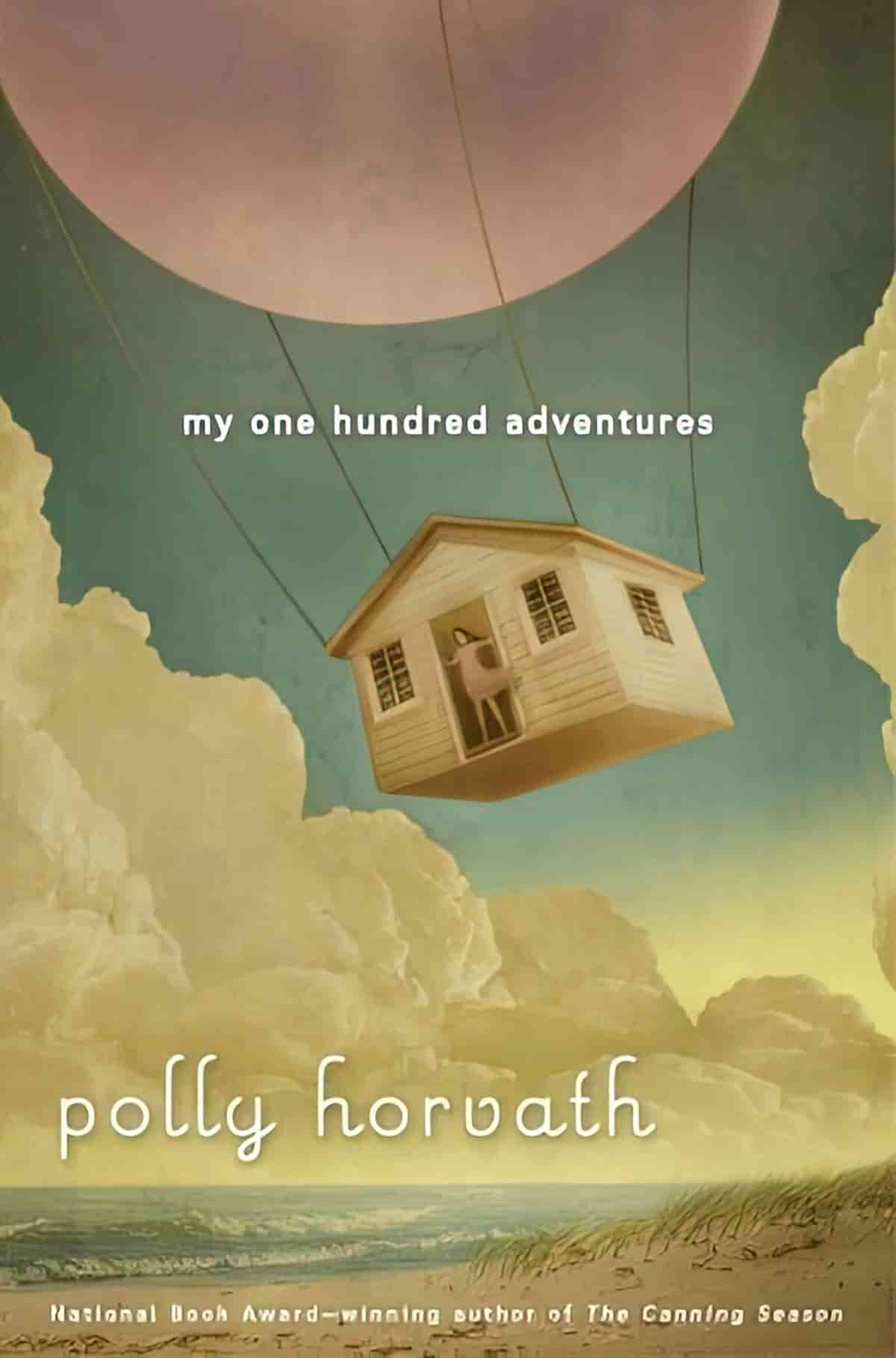

Jane is 12 years old, and she is ready for adventures, to move beyond the world of her siblings and single mother and their house by the sea, and step into the “know-not what.” And, over the summer, adventures do seem to find Jane, whether it’s a thrilling ride in a hot-air balloon, the appearances of a slew of possible fathers, or a weird new friendship with a preacher and psychic wannabe. Most important, there’s Jane’s discovery of what lies at the heart of all great adventures: that it’s not what happens to you that matters, but what you learn about yourself.

And don’t miss Polly Horvath’s Northward to the Moon, the sequel to My One Hundred Adventures.

- What do you know about airships?

- Have you seen airships before, in the sky or in certain types of stories?

- What does the presence of an airship add to the feel/mood/setting of a story?

What is an airship?

Airships are also called ‘blimps’ and are seen quite often at sporting events as advertising vessels. Airships are also called ‘dirigibles’.

In fiction, airships are a common sight in alternative superhero depictions of New York. You may recognise the airship from DC’s Batman series.

Airships were once a fairly common sight in Northern skies.

The Legacy Of The Hindenburg

The most famous real-life airship is The Hindenburg, which caught alight during an electrical storm while trying to land on May 3, 1937. Due to a limited supply of helium (mainly in America), hydrogen was used to give airships lift. Hydrogen is lighter than air but is highly flammable.

The Hindenburg was a massive airship — perhaps the airship equivalent of The Titanic — affordable only to the super rich, because a one-way ticket from Europe to America cost the equivalent of a car. Flight was brand new to humans, and it’s easy to forget that the passengers had never seen the world from a bird’s eye view before.

Everybody looks up and they see this graceful, slow moving, big object, and that seems to be something people are just fascinated with.

Mark Kynett (Senior pilot, Goodyear Blimp) speaks on the documentary When Weather Changed History: The Hindenburg Disaster.

The fact that documentaries are still being made about this disaster shows that we are still fascinated by airships.

If the Hindenburg disaster had never happened, history would have played out differently. We would be living in a slightly different world as a result. No doubt a Hindenburg-type disaster would have happened at one point or another, but it’s fascinating to consider how the history might be slightly different. Airships are often used in fictional worlds which are basically real, but are slightly off-kilter. The presence of an airship helps to create such a setting.

The Hindenburg was thought to be infallible. The vessel was referred to as “Queen Of The Skies”. This connection to royalty is fascinating because the airship as metaphor for royalty and celebrity is a good one. When common people see celebrity it’s easy to forget that these are human beings who are really not infallible at all. Often, celebrities die younger than they should, in ‘fiery’ events which captures the media’s attention.

The metaphor of height differential and flight is common in fiction. Altitude is also reflected in English idioms. We say ‘rise to the occasion’ or ‘look up to’ someone. In this story, a Princess is aware of the world that surrounds her. She can’t understand why she has been born into royalty when the role could just as easily have been given to some other girl. This doesn’t exactly fill her with confidence, as she prepares to deliver her first significant speech as a princess who has recently come of age. In an attempt to elevate herself in her own mind, she imagines herself on an airship, looking down on the world. Common wisdom about calming nerves before a presentation or speech often includes metaphors of lightness and flying: We are often advised to fill our lungs with air by taking deep breaths. We attempt to ‘rise above it’, to ‘glide’ into a room. We may feel ‘light-headed’. All of this relates to the metaphor of the airship.

The Long-Lost Home

In number six (and final) of the Incorrigible Children Of Ashton Place series, the main character is stuck in a Russian village but must make her way home to England. I’m guessing it involves a hot air balloon. Publication due end of 2017.

A miniature air balloon is also used in this episode of Wallace and Gromit.

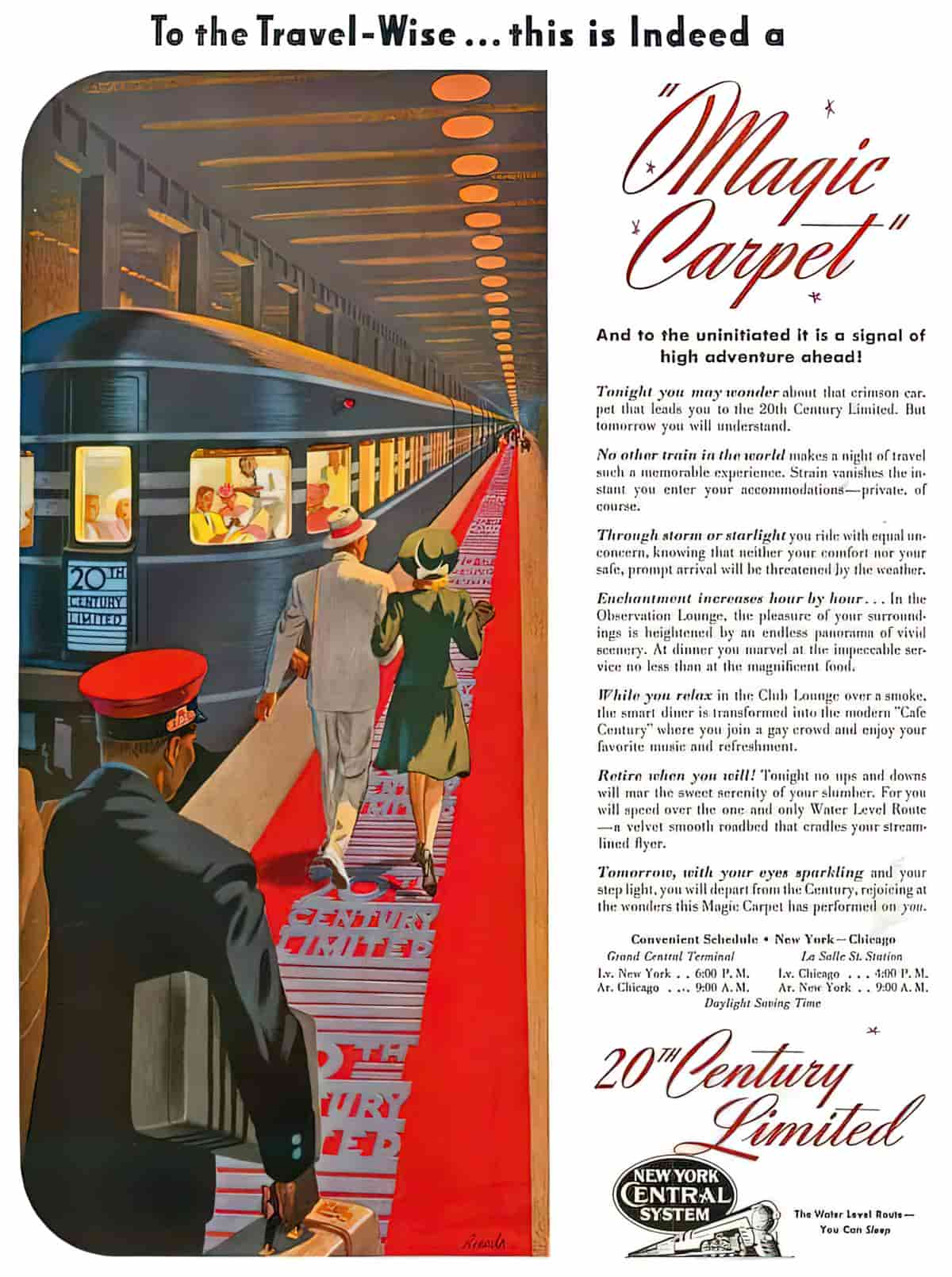

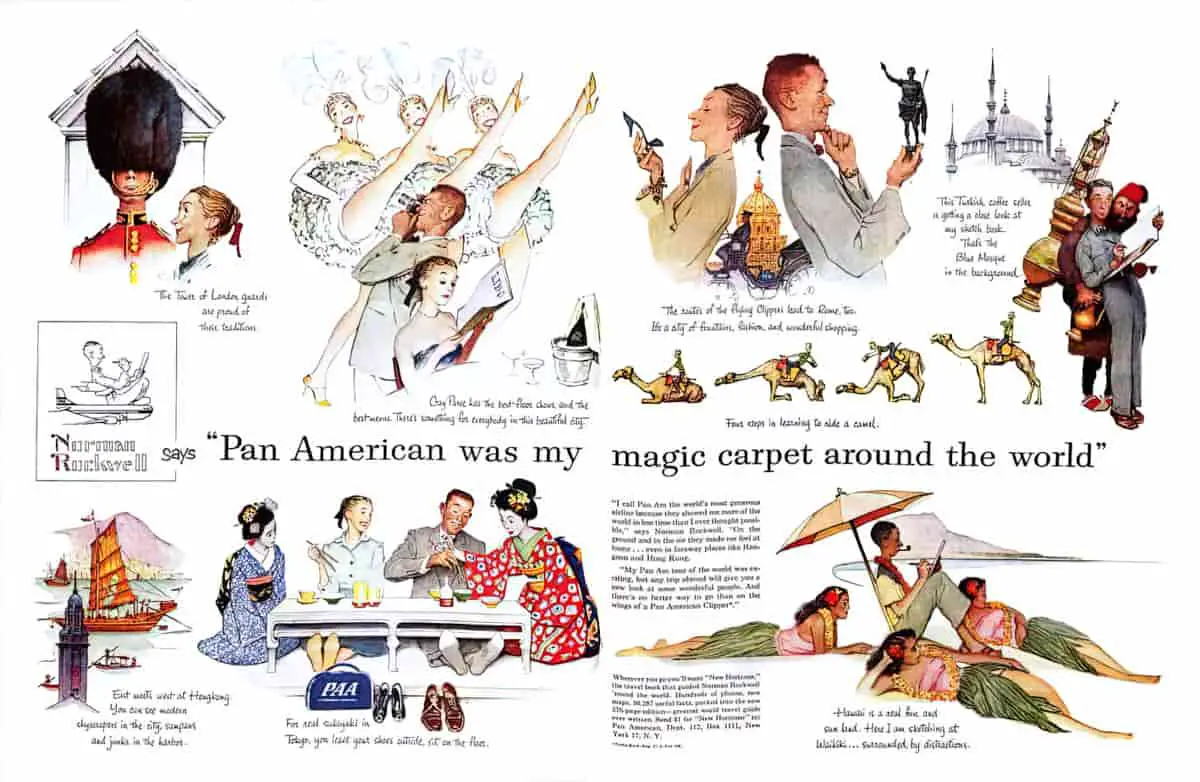

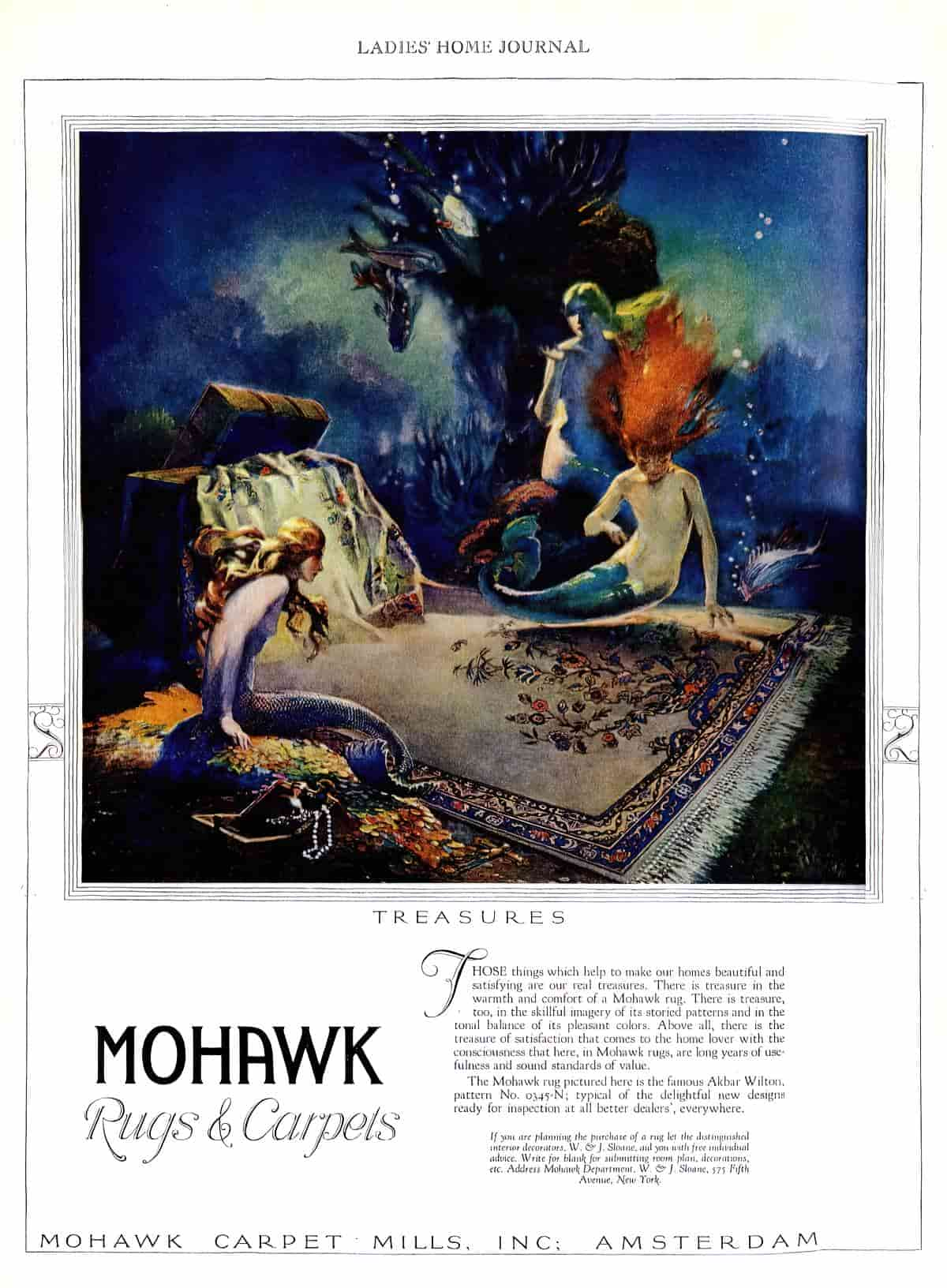

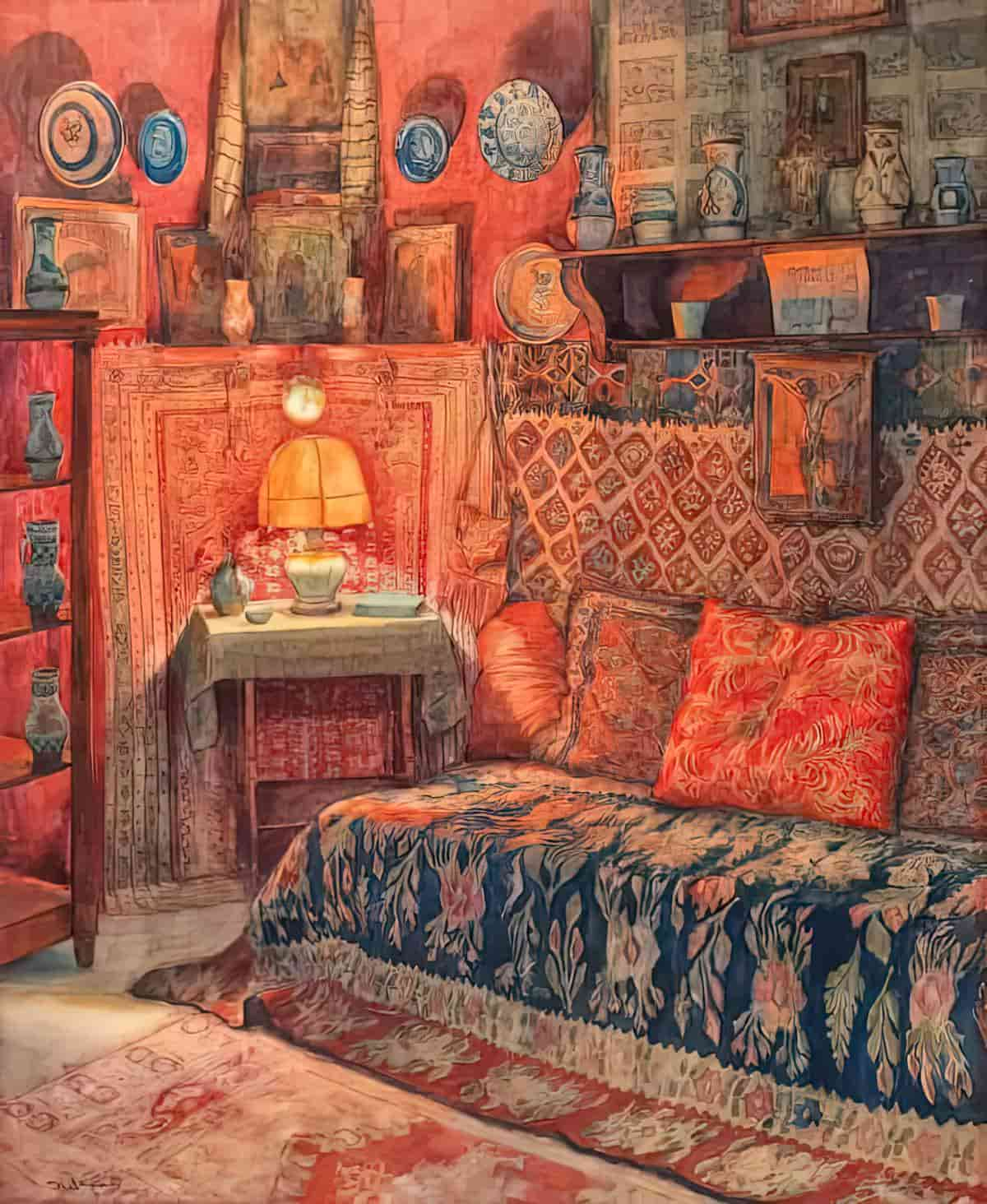

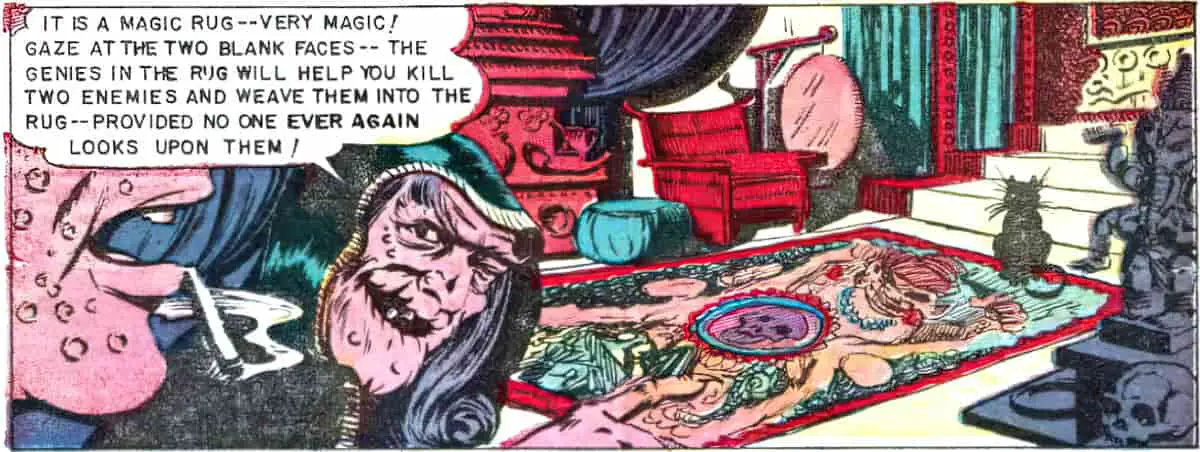

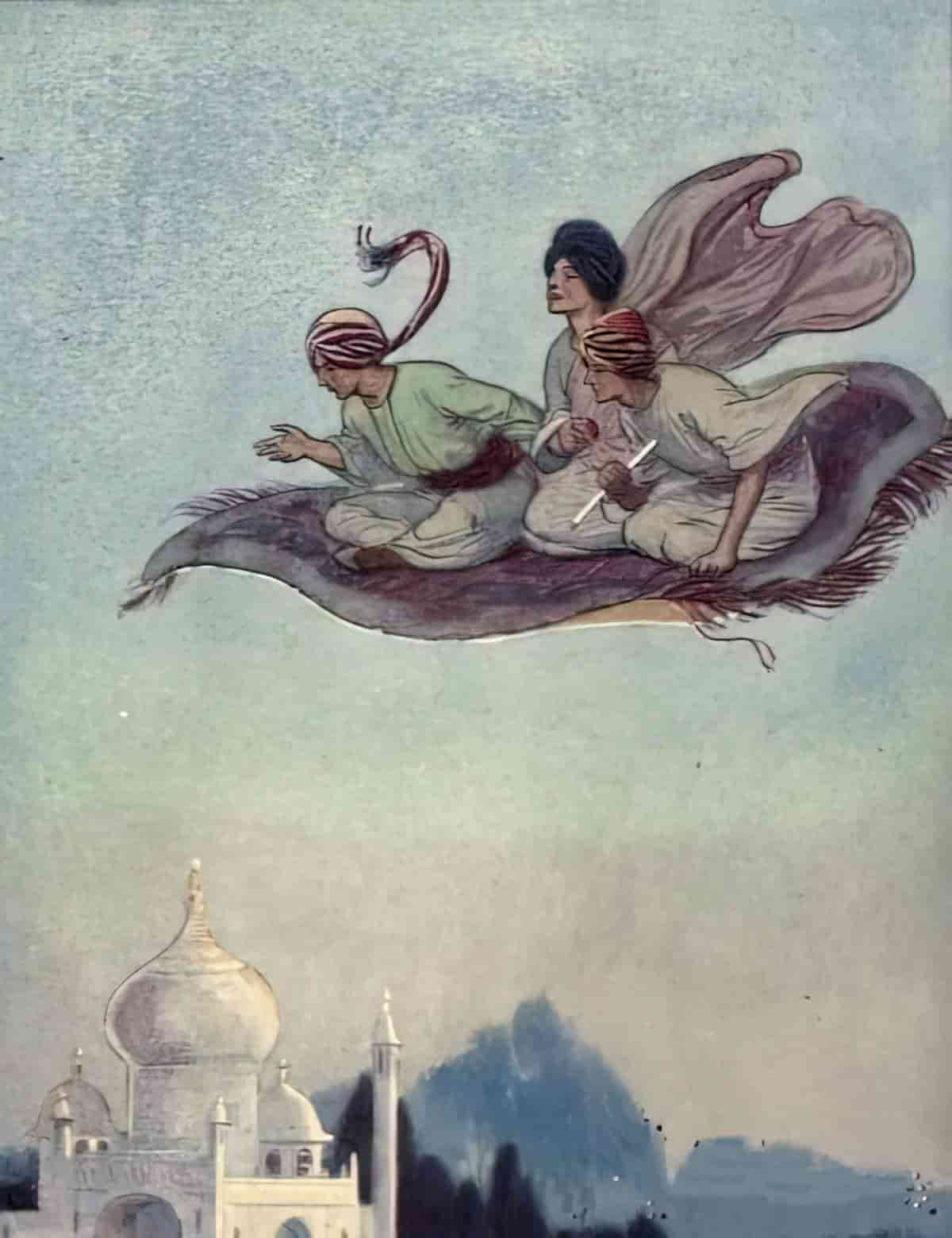

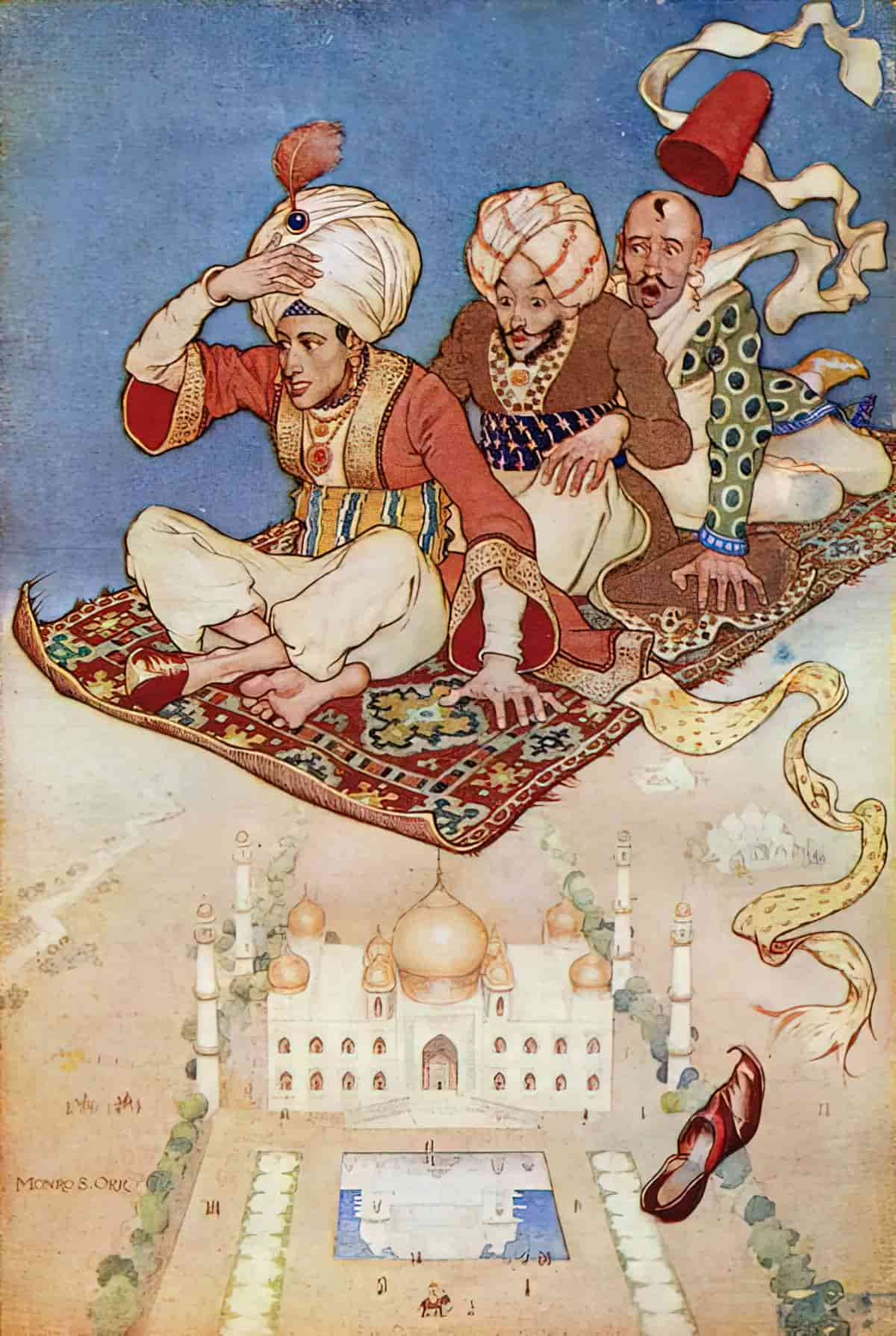

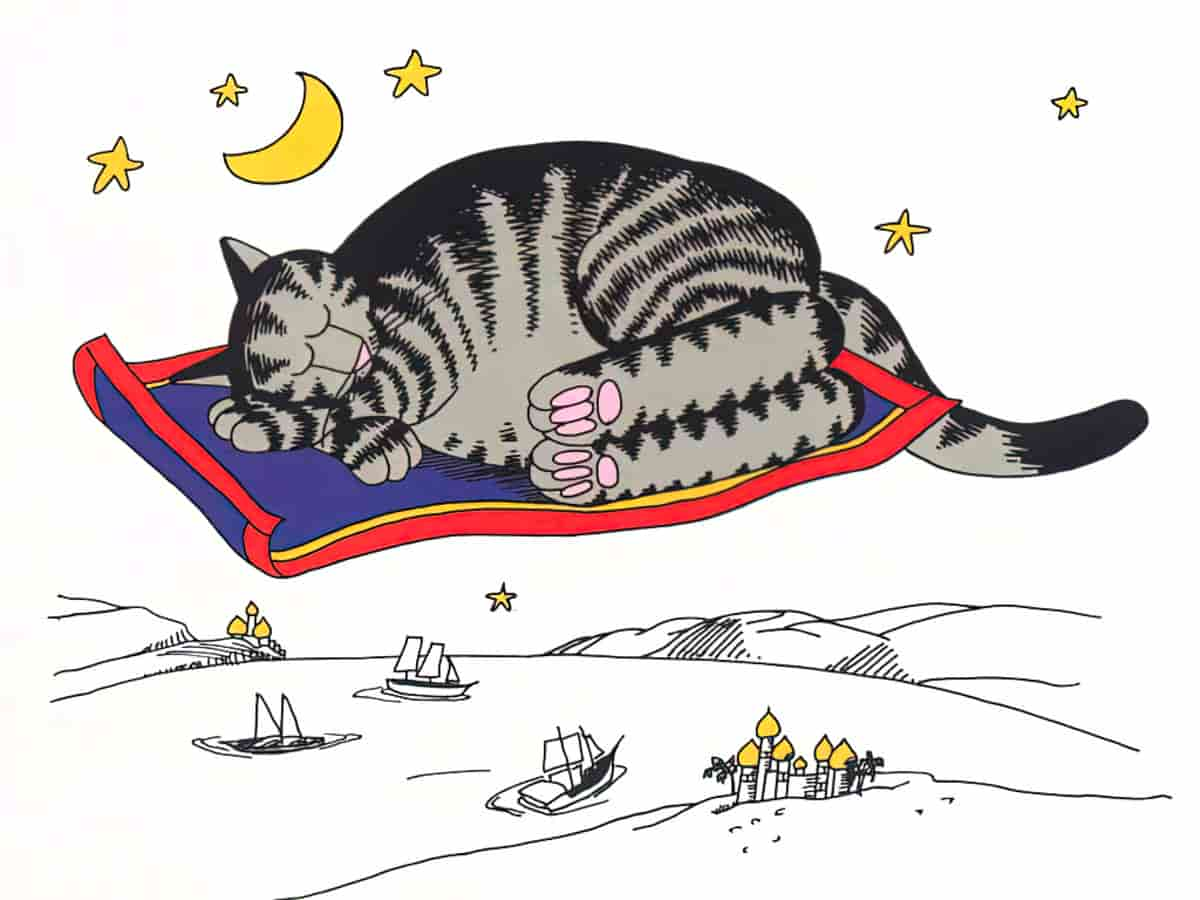

FLYING CARPETS: A SPECIAL KIND OF FANTASY TRAIN

Symbolically in stories, a flying carpet functions like a train crossed with a garden… that flies.

In fairy tales, certain magical items tend to be linked to certain modes of transference. (For more on that, see the work of Vladimir Propp.) Common magical aids which make their way into the main character’s possession: horses and magic carpets. The difference? Horses tend to be given to the main character whereas magic carpets are most often stolen. Likewise, magical handkerchiefs are usually stolen.

Foucault reminds his reader that carpets “were originally reproductions of gardens” and that “the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space“. His reference is to the portability of rugs, but in the context of children’s literature there are numerous instances of flying carpets that can literally move across space, juxtaposing different sites while themselves providing a location for action. If a ship or a flying carpet can be a heterotopia, surely we must accept the possibility that a train can also.

Utopian and Dystopian Writing for Children and Young Adults, edited by Carrie Hintz, Elaine Ostry

Why carpet? What made storytellers look at a carpet and think, you know what, I can imagine sitting on that and being whisked away. Carpet is not the only household item to have captured popular imagination in this way; witches and their broomsticks are another standout example.

Mundane as carpet seems now, carpets were once a luxury item. Persian rugs remain expensive decorative items. The addition of a foreign-crafted, highly decorative rug to one’s home affords Western households an exotic flair, prompting imaginative flight.

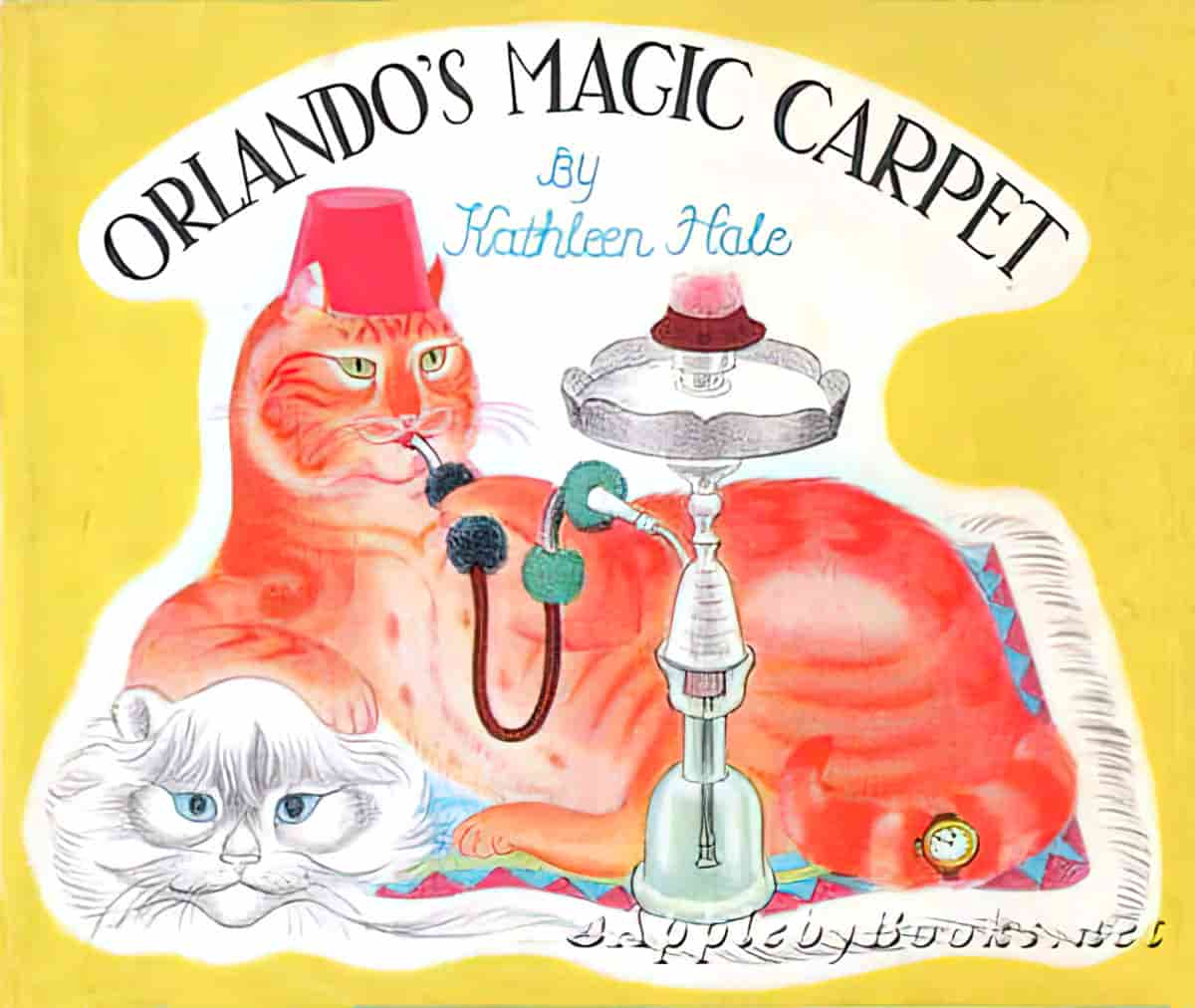

Nothing says ‘Boss move’ like keeping a living friend called Fatima as your living magic carpet. Orlando’s Magic Carpet (1958) is by a British author illustrator and is number 14 in a series about Orlando The Marmalade Cat. The interior illustrations are black and white.

Cats are especially well-suited to flying around on magic carpets since they spend so much time sleeping, often on carpets.

THE SYMBOLISM OF BROOMSTICKS

Witches and broomsticks are connected, with the idea that witches use broomsticks to fly to their witch meetings in the night. Why the broomstick? And which way are you meant to sit on one? See: The Symbolism of Broomsticks.

For women, broomsticks have been a symbol of oppression, inverted in witch symbolism to allow escape from domestic drudgery.

VARIOUS FLIGHT MOTIFS ACROSS LITERATURE

Bella’s house likes to travel, setting sail across the ocean while everyone sleeps. Bella’s parents don’t mind as long as the house is home by daylight.

One night, Bella has a wonderful idea for her grandfather’s birthday. She wants to find a figurine he made of her grandmother, lost overboard in an accident. Bella and the house go in search, but things don’t quite go according to plan…

(This book is an example of a children’s novel described as ‘whimsical‘.)

In this magical middle-grade novel, ten-year-old Gabrielle finds out that America isn’t the perfect place she imagined when she moves from Haiti to Brooklyn. With the help of a clever witch, Gabrielle becomes the perfect American — but will she lose herself in the process? Perfect for fans of HURRICANE CHILD and FRONT DESK.

It’s 1985 and ten-year-old Gabrielle is excited to be moving from Haiti to America. Unfortunately, her parents won’t be able to join her yet and she’ll be living in a place called Brooklyn, New York, with relatives she has never met. She promises her parents that she will behave, but life proves to be difficult in the United States, from learning the language to always feeling like she doesn’t fit in to being bullied. So when a witch offers her a chance to speak English perfectly and be “American,” she makes the deal. But soon she realizes how much she has given up by trying to fit in and, along with her two new friends (one of them a talking rat), takes on the witch in an epic battle to try to reverse the spell.

FURTHER READING

What are the best children’s books on flying? from The Guardian

Children’s Literature and Flight, focusing on planes and space travel

Header illustration: by Anton Von Beust “The Flying Machine”, 1895