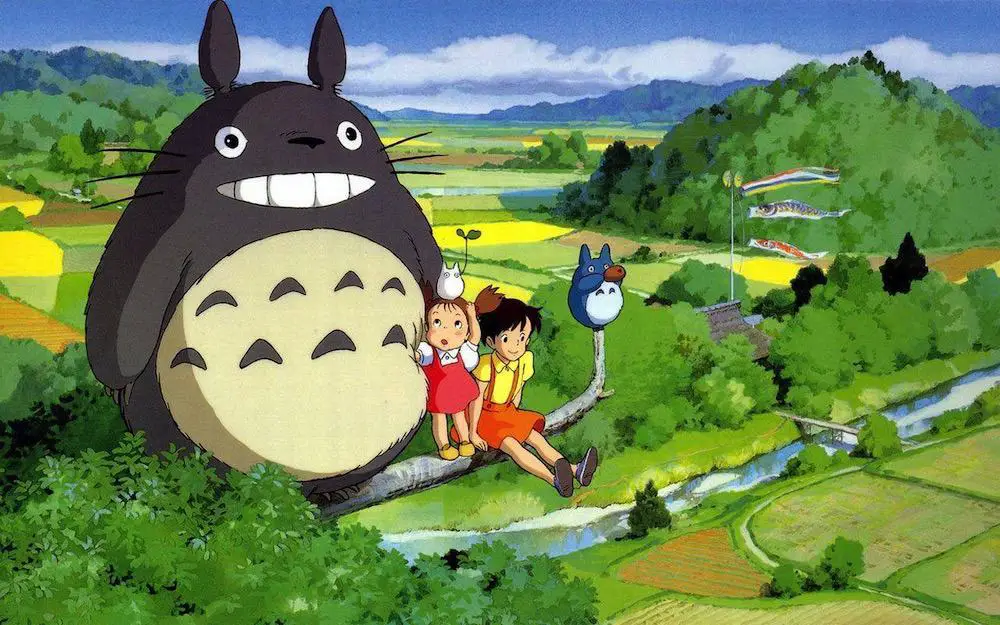

My Neighbour Totoro (1988), from Japan’s Studio Ghibli, is one of the few genuinely child centred films in existence. In contrast, most films out of DreamWorks and Pixar contain dual levels of meaning, including jokes only the adult co-viewer will understand, or emotional layers inaccessible to children.

For instance, in Toy Story 3 Andy says goodbye to his childhood when he says goodbye to his toys. This evokes the emotion of nostalgia and sadness in adults. Test audiences revealed that children under about 13 have a completely different reaction to this scene — they identify with the toys and feel happy, probably wondering why the adults are tearing up. Nostalgia is one of the few specifically adult emotions.

In contrast, The Good Dinosaur (2015) didn’t garner great reviews. Some critics suggested it’s a fine story for kids, but adult viewers expected a layer aimed specifically at them. But there is no ‘adult layer’ to The Good Dinosaur, which ranks as Pixar’s second-worst rated movie (above Cars 2). In the West adults have been trained to expect kids’ films with separate layers just for us.

My Neighbour Totoro is different altogether.

When My Neighbor Totoro , directed by Hayao Miyazaki, came out in 1988, the public treated it only as a “child pleaser”. Yet Japanese people soon realized that My Neighbor Totoro was something more; it is actually a thought-provoking film. It is now considered one of the most acclaimed films for children and adults.

Reiko Okuhara

Here’s my thesis: Studio Ghibli achieves what Pixar and DreamWorks have thus far not managed:

- A film which appeals to all ages

- without alienating the preschool viewer from any single part of it.

- Adults and children will be laughing at the same moments

- experiencing very similar emotions simultaneously.

I first watched Totoro in 1995 as a 17-year-old exchange student in Japan, where it was aired on national TV one wintry Sunday afternoon. The air time suggests family viewing — a film for all ages. I’d be surprised if I ever met a Japanese person who hadn’t seen this film, regardless of age or whether they have children of their own.

Fast forward a sociological generation, My Neighbour Totoro was one of the first films I showed my Australian daughter. As I expected, she was captivated as a toddler.

We rewatched it last night. When she first saw it she was the age of Mei; now she is the age of Satsuki. Although it had been years since last viewing, her delight showed me the imagery remains deeply etched in her memory. Revisiting the world of Totoro felt like revisiting a holiday destination from early childhood.

Ponyo is another Studio Ghibli film aimed squarely at a very young audience.

SETTING OF MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO

JAPAN

I much prefer the Studio Ghibli films set unambiguously in Japan. The European-inspired Japan as depicted in films like Kiki’s Delivery Service fall into uncanny valley for me. Totoro is set in Japan.

The story is meant to be set in Tokorozawa. If you’re using Chrome as your browser, here it is on Google Earth. This is where Miyazaki lives.

If you visit Japan you can explore a replica of Satsuki and Mei’s house.

If you would like to visit the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, make sure to book your tickets from outside Japan, because overseas bookings are given preference. Perhaps unfairly, Japanese people booking from within their own country must book many more months in advance.

ERA

It’s not easy to guess at the era of My Neighbour Totoro unless you watch it very closely and can read Japanese. (Bear in mind that the main audience — Japanese toddlers — also cannot read Japanese.) The story could be set anytime from Miyazaki’s own boyhood until the 1980s when it was released.

Adult fans have looked really closely and realised it could be set in any number of years within the 1950s. Hayao Miyazaki has been pressed to divulge when, exactly, it’s meant to be set. He replied, “It’s supposed to be 1955, but we weren’t terribly thorough in our research. What came to mind was ‘a recent past’ that everyone can relate to.”

Note that Miyazaki uses the word ‘everyone’. That includes children. He hasn’t created any part of this world that 1980s children would be unable to understand without explanation.

Apart from the minor calendar clues within the intratext of the film, My Neighbour Totoro could easily have been set when it was made, in the 1980s. We don’t get a glimpse of life in the cities because the story arena is contained to a very small part of Japan.

The second year I went to Japan (1999) I stayed in a dormitory attached to a university. This dorms were nestled under a mountain, which sounds lovely, except it hadn’t benefitted from a single bit of maintenance since it was constructed at the end of the second world war. If I hadn’t ever visited the city, I might as well have been living in post-wartime Japan. This was a hugely different experience from my high school exchange student year in Yokohama, one train ride from Tokyo, tech mecca setting of futuristic fantasy. I recognise the house from My Neighbour Totoro — the tiled sink, the wooden items, the country manners.

Country Japan has always been bifurcated from urban Japan — a point of pride and also a point of ridicule. The word ‘inaka’ might loosely translate as ‘rural/country’ in English, but it sounds pejorative and insulting as well. (Imagine ‘bumpkin’ on the end of it.)

However, this is not Miyazaki’s view of rural Japan. For Miyazaki, the natural parts of Japan contain ancient magic, and a visit into wilderness afford a trip into the deep subconscious. The forests which surround this old homestead of My Neighbour Totoro function as a forest functions in a fairytale.

IS THIS A UTOPIA?

Does the setting of My Neighbour Totoro count as a genuine utopia? According to Maria Nikolajeva, there are seven requirements of a utopian setting and Totoro almost fits, except for number six: Absence of death or sexuality. The sick mother in hospital is a constant reminder that loved ones can die. Satsuki and Mei are terribly worried about their mother and this drives their actions.

Miyazaki adapted Mary Norton’s The Borrowers (released as The Secret World of Arrietty), which also includes the spectre of death with the child sick in bed. Perhaps Miyazaki wants to avoid sentimentality, which is a danger in creating genuine utopias. Genuine utopias are also quite difficult to set a film-length story in, because suspense must come from somewhere. Perhaps ‘unease’ is a better word than ‘suspense’.

Helen McCarthy is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation and has said that Death in Totoro is simply ‘there’. Death is presented as part of being alive.

Miyazaki does two very difficult things in this film with considerable delicacy and grace: he makes a film at a child’s pace and on a child’s level; and he allows death to assume a major role in the movie without demonising or personalising death.

Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation

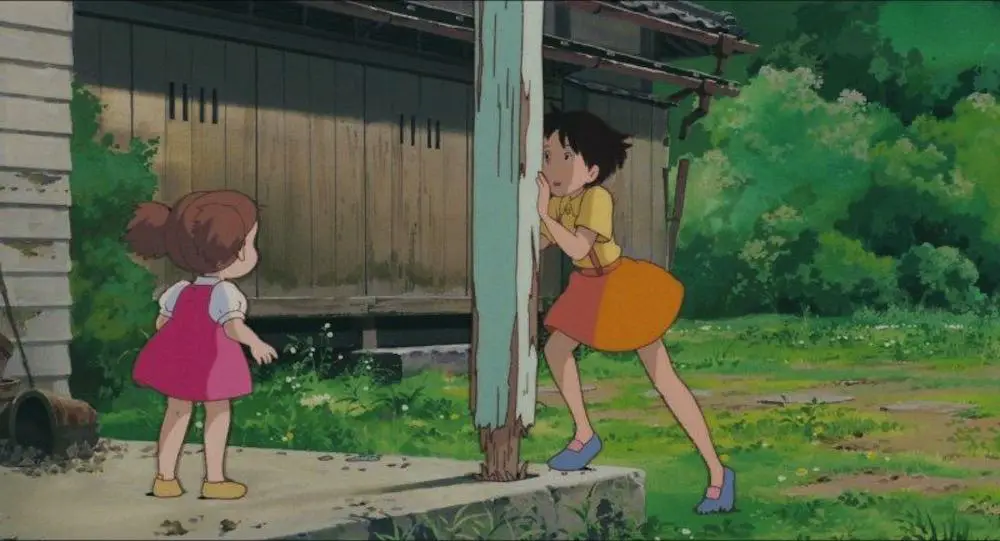

The house itself might be considered a bit of a death trap. Our own pergola fell down a few years ago and it was a mission keeping everyone away from it for their own safety. But here, the girls come closer to calamity than they realise when they use the rotting post as a play thing:

This traditional old homestead also has a well — another common death trap, though it exists only as part of the background scenery.

The soot gremlins may or may not indicate the presence of evil. The girls no longer have a safe home. I believe young children will find this house as creepy as the characters do.

However, we might put forward the argument that any Hayao Miyazaki film is a moral utopia:

[T]hose who are familiar with Miyazaki can trace the film’s modern success to his stubborn moral mind. Reluctant to put his characters into straightforward ‘good’ and ‘evil’ boxes, the Ghibli stalwart nevertheless rewards the pure of heart and punishes greed and gluttony. It’s a trait that wasn’t missed by Roger Ebert, who described Totoro’s small kingdom as, “the world we should live in, not the one that we occupy.”

Little White Lies

THE MEANING OF TONARI

Despite the English translation of the title, ‘tonari’ does not just mean ‘neighbour’ as in ‘those who live in the place next door’. Tonari is a wider word than English ‘neighbour’ suggests, and can mean ‘next to’, or ‘alongside’. Imaginary creature Totoro is ‘alongside’ the girls at every step of their journey (as well as dwelling ‘nearby’.)

PORTAL FANTASY

One rule of portal fantasy — there is a transition between the ‘real world’ and the ‘fantasy world’. The audience must be allowed to linger in this transitional space for a little while. Ideally, a scene or two will be set inside the transition, or right beside it. In this case, it’s the tunnel made of branches. The father even joins the girls there, blurring for them the sensible, rational adult world and the fantasy play world they have created.

It appears as if someone—probably Big Totoro himself—has invited Mei into the fantasy world. Awakened by the little girl, he appears to be startled not by her presence but by her audacity. Mei’s seclusion has led to Totoro’s invitation to his world; the child archetype acquires the protection of nature, alone and away from motherly care. Mei’s entrance into the fantasy world reminds the audience of the beauty and splendor of nature, which the present generation seems to have forgotten.

Reiko Okuhara

MYTHOLOGY AND INTERTEXTUALITY

One of the first games we see the Kusakabe girls playing is a Cowboys and Indians fantasy. I haven’t seen modern children mimic the war cries of Native Americans — Westerns have evolved into anti-Westerns, we are a little more enlightened. There is no longer the romance of American expansionism — we no longer buy toy cowboy costumes for our boys as par for the course. This childhood game does plant the story quite firmly in the 1950s when, even in Japan, American culture was having a big influence on children’s fantasy lives (as well as in every other way).

Later the girls are disappointed to find their acorns won’t sprout. But in a fantasy scene quite clearly inspired by English tales such as “Jack and the Beanstalk”, they use arm movements to create a magical force. The trees grow huge in an instant.

MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO: THE JAPANESE WIZARD OF OZ?

We Westerners like to view non-Western art through the lens of Western art. It has been suggested that My Neighbour Totoro is ‘The Japanese Wizard of Oz’. This may be useful as a hook for a Western viewer otherwise disinclined to watch anime on its own terms.

Perhaps one of the biggest reasons for Totoro’s success is that everyone has their own interpretation of what it means. While the physical appearance of the title character has been compared to everything from an owl to a seal to a giant mouse troll, on a metaphysical level the theories run even deeper. In Miyazaki’s book of essays ‘Starting Point: 1979-1996’, Totoro is described as a creation of Mei and Satsuki’s imagination, a gentle giant who guides them through their mother’s illness.

Some believe Totoro to be a Kami (a spirit tied to nature) belonging to the camphor tree which Mei falls into the belly of while she’s out playing. The tagline on the original Japanese poster translates as, “These strange creatures still exist in Japan. Supposedly,” which summons thoughts of old souls and endless wisdom. Ultimately, you can project whatever you want onto Totoro.

Little White Lies

THE THREE BILLY GOATS GRUFF

If you grew up in non-Scandinavian country, what was your first introduction to trolls?

Near the end of the film, Satsuki and Mae are shown reading The Three Billy Goats Gruff on a futon with their mother. The creature on the book looks like the creature Totoro, which suggests Mei imagines him up, inspired by the Norwegian folktale.

When Mei ‘meets’ him, she knows exactly who he is. “You’re Totoro!”

In Japanese Three Billy Goats Gruff translates to 三びきのやぎのがらがらどん (Sanbiki no yagi no gara gara don) in which the ‘gara gara don’ is onomatopoeia for the tripp trapp, tripp trapp of the first written Norwegian version (modified only slightly for English, without the double ‘t’s.)

But maybe Mei read a European version — the ‘trot trot’ of the goats sounds a little like Totoro. It’s significant that Japanese is a heavily onomatopoeic language. Children are excellent at making up their own, original onomatopoeia and I put it to you that Japanese children are excellent at i. Is Totoro Mei’s phonetic rendition of trotting?

Alternatively, ‘troll’ is transcribed as ‘tororu’ in Japanese. A small Japanese speaking child could easily pronounce the word wrongly and come up with Totoro, because Totoro is easier to say than Tororu.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO

At first glance, My Neighbour Totoro does not follow The Rules Of Story as described by numerous (Western) story gurus. It just feels… different, somehow.

The story [of Totoro] is made up of a series of incidents or episodes, almost none of which I’d classify as a plot point, per se. The only truly tense moment comes late in the film, when Mei runs off to the hospital by herself, worried her mother is in danger. This turns out to have been a false alarm, and everyone is soon reunited. The whole thing is resolutely low-stakes and gentle, its narrative lumpy and relaxed.

Bright Wall, Dark Room

I’ve been thinking about how much Western storytelling trains us to expect that writers show the audience where they’re going right up front. Main characters have to be introduced right away. Twists have to be foreshadowed. Inciting incident in the first 10% etc. BUT Many of my favorite stories, especially Asian ones, don’t adhere to these “rules.” In My Neighbor Totoro, Totoro doesn’t appear until 30 mins into a 90 min film. The slow sense of discovery makes the film enchanting. Can you imagine any American film waiting until the 33% mark?

@FondaJLee

But look a little deeper and My Neighbour Totoro is a tightly plotted fantasy with a classic mythic structure.

I have no trouble doing my usual breakdown of it, but here’s the thing we need to understand about My Neighbour Totoro: It is much more like a picture book plot than a Pixar plot, and it’s important to understand the concept of the Carnivalesque. (This is why My Neighbour Totoro has been compared to Where The Wild Things Are — the stand out Western example of carnivalesque children’s literature.)

SHORTCOMING

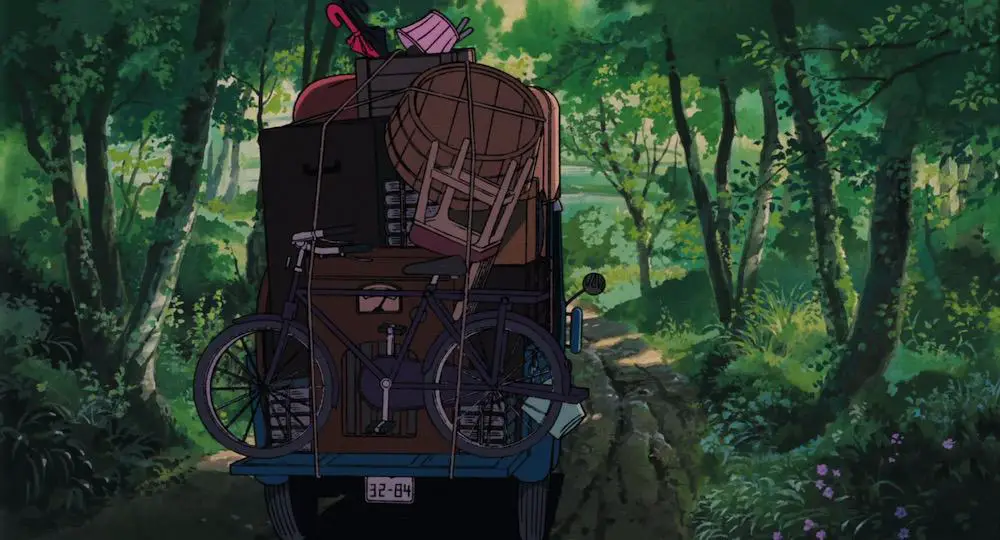

Satsuki and Mei are enduring an upheaval — in common with the beginning of many children’s stories, they are at the tail end of having been moved from some unknown prior location to a creepy big house in the country.

Before they can feel at home here they must face their fears of the unknown.

There’s a much bigger unknown which the girls are initially able to put to the back of their minds, distracted by the newness of the creepy house: Their mother is ill. Like Satsuki and Mei, the audience doesn’t know the nature of this illness. We are kept in a state of ignorance, which may be worse than actually knowing. This is the common experience of childhood — even when children are told things, we don’t know what it means. Not really. This makes childhood scary.

Miyazaki also gets rid of the mother by making her too sick to care for them — a very common plot device in children’s literature, especially in America.

But Mei in particular is the Divine Child archetype, both vulnerable and invincible at once. (Jungian.) The audience understands this contract from the beginning, even if we don’t know Jung’s word for it — nothing really bad will happen to Mei.

The sibling duo in which the younger child is at one with fantasy and imagination while the older child is on the cusp of adulthood, is common in storytelling:

Unlike Mei, who fully enjoys her childhood, her elder sister is about to enter womanhood. Satsuki resembles Wendy in Peter Pan, who must work to believe in Peter, while her younger brothers have no problem believing in Neverland.

Rieko Okuhara

DESIRE

At the deepest level, Satsuki and Mei want their mother to get better and to join them in their new house. But this doesn’t make for a story. There needs to be a more specific desire, one that the characters might actually achieve.

This is where the story turns carnivalesque. Started by the younger and therefore more imaginative Mei (in a sequence reminiscent of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe), they invent (or discover) a magical world as proxy for their subconscious. By entering into this world they will:

- Have heaps of fun (carnivalesque)

- Face their deepest fears (mythic)

OPPONENT

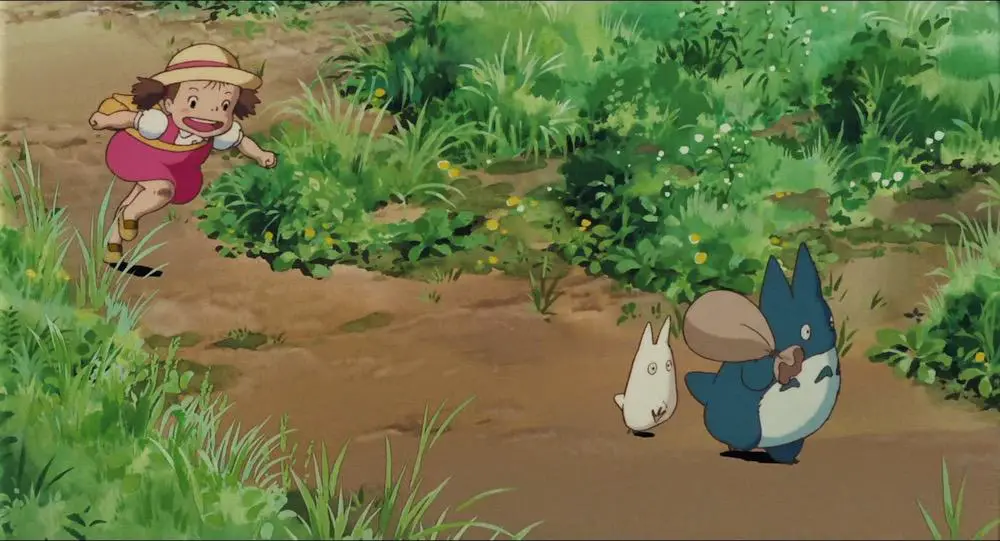

In a carnivalesque children’s story, supernatural/mythic creatures appear and they may appear scary. In this case, it is the large Totoro’s size. Notice how Mei at first encounters small, rabbit-sized Totoros — this correlates to how her fears intensify over the course of the story. In Japan, these totoros are known as Big Totoro, Medium-sized Totoro and Little Totoro. (This reminds me of The Three Bears.)

But Totoro is also furry like a welcoming great bed.

Despite this, Totoro has an element of danger. I’m thinking, if the creature rolls over, Mei could easily be squashed. The scene with Mei and Totoro contains a minor ‘Battle’ of a big sneeze, as Mei fiddles with Totoro’s whiskers. Many children’s picture books feature an outsized bodily function as the climax, most notably in fairytales such as The Three Little Pigs, but also in Yertle The Turtle and Julia Donaldson’s Wake Up Do, Lydia Lou!

In a cosy story like My Neighbour Totoro, the main characters will meet allies (helpers) along their mythic journey.

First there’s the father.

The father—almost like a Wise Old Man, another archetype figure—seems to understand the rules of the gods’ world and explains them to his children.

Rieko Okuhara

Then there is Granny. Mei is scared of her at first, perhaps because she is new, perhaps because she is old, perhaps because she is associated with a scary house. The Granny, like many elderly characters in children’s stories, lives in her own version of a fantasy world. She tells the girls quite confidently that if their mother ate her fresh homegrown vegetables, her illness will clear right up. This is not an especially responsible thing to tell a child, and it is what sets Mei off on her journey to deliver the corn cob to her mother. (This has been foreshadowed by Mei telling her father that she is a big girl now and is off to do ‘errands’. The father thinks nothing of this at the time.)

The boy next door (Granny’s real grandson) is positioned as a natural opponent because he is a boy. Satsuki declares that she does not like boys. However, Kanta reveals his kindness by offering the girls his umbrella — a well-known trope in Japan, where people will indeed share their umbrellas with you if you are caught in a downpour. (Downpours are common during rainy season — when Kanta is chastised by his mother for failing to take an umbrella, there was a surefire bet it would rain heavily.)

Totoro turns up at the bus stop at night — a scary prospect for the girls, whose deeper fear is: “What has happened to Dad?” Dad hasn’t turned up when expected. Without their father, the girls would be utterly alone in the world. So once again, Totoro turns up as a proxy for their fear, and the girls transform him (or her — where did those mini Totoros come from?) into a non-threatening, childlike creature who is so unassuming he is startled by heavy raindrops falling onto the umbrella lent to him by the girls.

PLAN

Satsuki and Mei first explore their new house. If they explore every nook and cranny they will understand its mysteries. Ergo, they will not feel scared. Exploration of the scary house occupies a good chunk of the beginning. They find ‘soot gremlins’ — very much in line with the sort of creature found throughout traditional Japanese folklore, but actually invented by Miyazaki himself. In the West we have dust bunnies, which are more hairy than sooty.

In a suspenseful story for adults (say, anything from the thriller/detective genres), there will be a chase sequence. Here, too, there is a chase: Mei chases after the intriguing little creatures. In other words, it is Mei who drives the action, not the other way round. The utopian, cosy atmosphere would have been punctured had the Totoros been chasing Mei instead.

Mei also drives the action by visiting Satsuki at school.

Finally, she takes off on a one-girl mission to save her mother. Notice that before she does so, the sisters have an argument.

BIG STRUGGLE

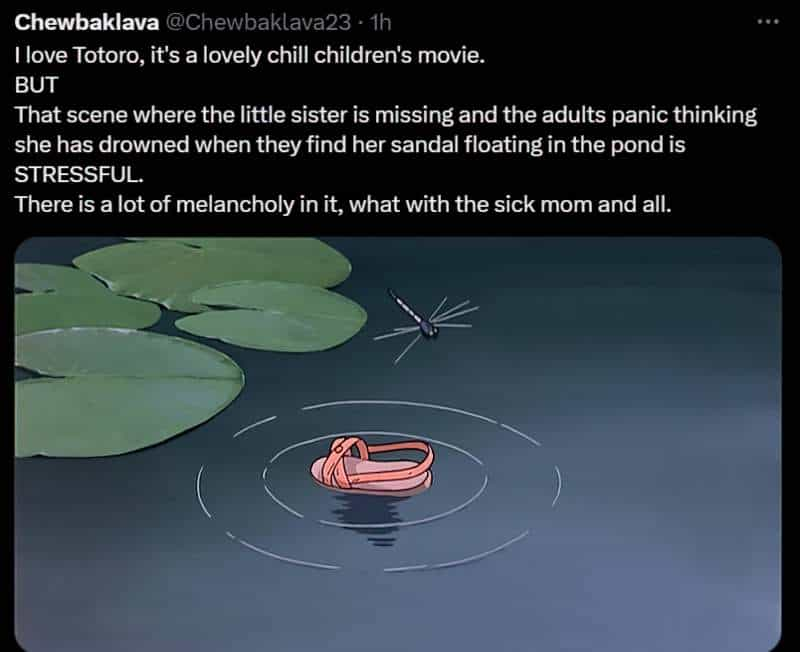

The Battle sequence, in which the village searches for Mei, is similar to cross-genre ‘lost child’ sequences. We wonder if Mei is dead when a child’s sandal is found. (I wonder who it belonged to?)

Satsuki finds Mei by visiting Totoro. Totoro is able to fly, and can also summon the cat bus. Satsuki saves Mei by making use of forest magic. At least, that’s the fantasy layer of the story.

More literally, Satsuki may summon the courage to find Mei of her own accord, imagining that she has the protection of mysterious, fantasy companions that she and Mei both conjured up, thereby leading her to Mei. By entering Mei’s imaginary Totoro world, Satsuki is also able to deduce that Mei has gone to the hospital with a ‘magic’ vegetable.

ANAGNORISIS

Ultimately, this is a story about two children who overcome their fears. They do this with the discovery that they are an integral part of the natural world. This discovery is proxy for the more mature insight they will develop later: That in order to be alive, we must also die. For now, though, their mother is not facing imminent death.

When Satsuki and Mei see their parents through the hospital window, they get the feeling everything with their mother is going to be all right. Often in visual storytelling, when characters come to some sort of realisation they are positioned at an elevated altitude. In this case they are up a tree — ostensibly so they can see through the window — symbolically because they now have a broader view on the situation and can put their mother’s illness in perspective.

This variety of Anagnorisis combines well with a Child Archetype such as Mei:

The child comes in the very beginning of life. Yet the child also symbolizes the rebirth of a new child; before the rebirth, death must come. The child archetype is an initial and a terminal creature, and represents the process of death and rebirth. When Mei sets out to the hospital to heal her mother, her family loses her for a period of time. The finding of the lost child symbolizes the rebirth of Mei. For Satsuki, finding Mei also means the rediscovery of her childhood. In the embrace of Satsuki and Mei, one witnesses the outcome of Mei’s death and rebirth. The child has combined the opposites, and the spirits are the witnesses to the event. The film ends with the happy smiles of people holding and hugging Mei and the spirits of nature looking over the cheerful scene from the top of the big camphor tree. Mei’s coming home completes a stage in the progression of human beings.

Reiko Okuhara

NEW SITUATION

No matter what happens to the mother, Mei and Satsuki are now emotionally equipped to handle whatever cards they are dealt. They have learnt resilience by means of the power of imagination.

Worth mentioning: The original tagline was “We brought what you left behind.” Clearly this refers to Mei’s delivery of the corn cob, but also works at the symbolic level — Mei reunites her family and village with the wonder of nature around them.

THE ART OF MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO

There is much to be said on this topic — I’ll focus on just a few things.

COLOURS

Taking a condense snapshot of main colours (depicted in the poster below), it’s clear how much of this film is set in the rural outdoors (green). The blue band takes the Kusakabe girls into the sky on a flight fantasy in the cat bus. Another green band takes them further into nature. Disregarding the light orange (which indicates the credits) notice the film is bookended by browns — the brown is the home, at first new and scary, by the end a true home.

PERSPECTIVE

More recently I’ve been following a discussion about how scenes in Totoro break the rules of perspective, as it is traditionally taught. At first glance scenes look like cartoonified versions of photographs, but that’s not the case. People have whipped their rulers out and discovered that the animators/background artists have broken traditional ‘rules’ (made in the West) to include more information in a single scene.

This, too, is more in line with the off-kilter perspective found in children’s picture books than in animation aimed at older audiences, in which case scenes tend to be beautiful for their technical prowess.

CHARACTER DESIGN

In a film aimed squarely at children, it is perhaps unusual that Miyazaki’s characters don’t have that big-eyed, anime look. On the other hand, the character designs are very much in line with picture books — an art form which has so far rejected the ‘anime look’. In fact, I’ve heard agents and publishers advise illustrators to steer well clear of manga-esque characterisation if the aim is to illustrate picture books. The movements of Totoro’s characters are beautifully accurate impressions of how children actually move — in common with how the best children’s book illustrators are able to depict realistic movement in their picture books. The scene in which Mei scoots forward on Totoro’s belly could not have been achieved without close observation of young children. Hayao Miyazaki is well-known for his attention to detail. If he needs to depict water flowing over rocks in a stream, he will go and watch water flowing over rocks in a stream.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Verbal Diorama podcast discuss My Neighbour Totoro.

Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro Soundtrack

A beloved Japanese anime move released in 1988, My Neighbor Totoro tells the story of two sisters, Satsuki and Mei, as they deal with the separation from their mother who is in the hospital, and their adventures with the forest creatures they meet called the Totoro. In Joe Hisaishi’s Soundtrack for My Neighbor Totoro Soundtrack (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), Kunio Hara analyzes the film’s score and image song collection composed by Joe Hisaishi. The movie’s catchy theme song, along with the rest of the music, contribute to the film’s nostalgic exploration of children’s inner lives and the power of imagination to combat the very real traumas of childhood. Part of the 33 1/3 Japan Series, this short book explores the collaboration between Hisaishi and Miyazaki Hayao, the film’s creator and director. Hara considers his subject from a variety of perspectives, from a musical analysis of key sections of the score and image album to an investigation of the film’s importance as an icon of Japanese pop culture. Kunio Hara is an Associate Professor of Music History in the School of Music at the University of South Carolina. His research centers on nostalgia, exoticism, and Orientalism in late Romantic opera and music in post-war Japan.

New Books Network