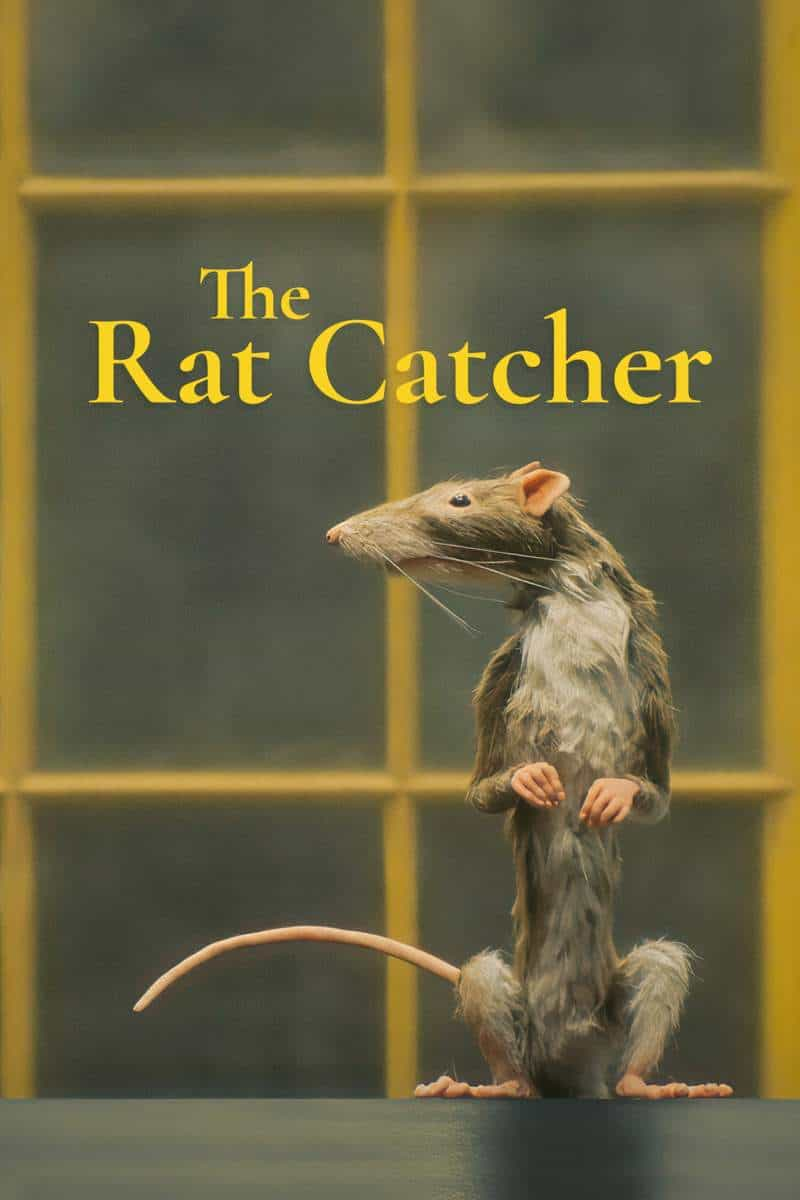

“The Ratcatcher” is a short story by Roald Dahl, the first of four stories in a series named “Claud’s Dog”. All four stories are included in Someone Like You, first published in 1954. Dahl wrote these stories while living at Wisteria Cottage, Amersham, a market town and civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “THE RATCATCHER” BY ROALD DAHL

- Describe the setting of this short story: time, place, a little about the social milieu.

- As you read, who did you feel most empathy with? Did this change as you continued reading?

- Roald Dahl uses a characterisation technique of describing a person as an animal. Which details help us to imagine the ratcatcher as an actual rodent?

- Can you think of other stories in which a character is described as an animal?

- Why is the ratcatcher compared to a rat? What does this tell us about his character?

- What is meant by the trickster archetype? Can you think of examples from literature/film/TV? Can you see a trickster in this story? Who is tricking who, and do they succeed?

- We know what Claud wants. (He wants the rats gone.) But what motivates the ratcatcher?

- What is a tall story? A shaggy dog story?

- What, in general terms, did Roald Dahl leave off the page, and why?

- What do you think the ratcatcher does after the story ends?

SETTING OF “THE RATCATCHER”

If you’ve read Danny The Champion of the World, Dahl has set this story in a similar setting: Working class people living in and around a village, with an aristocratic family living nearby.

Dahl likes to remind us that, despite human hierarchy, we are all human, all equal. Little is said about the aristocratic family in this story, except to say that even rich ladies attract rats.

PERIOD

Early to mid 20th century

DURATION

The story is a conversation and is basically isochronic, meaning the time it takes to read the story is about equal to the time it takes for the story to play out. (Gerard Genette came up with the term.) Of course, you never get a one-to-one exact match.

LOCATION

We are told this story takes place in Buckinghamshire. Most of us associate this area with Buckingham Palace, where aristocracy is propped up by regular folk who scurry around outside the limelight, keeping the place ticking over. (See where I’m going with that? The royalty symbolism is intentional, I believe.)

NARRATION OF “THE RATCATCHER”

Roald Dahl was careful with his narrative choices because this short story verges on the edge of revelry in animal cruelty. As I read, I felt increasing empathy for the rat victims. Dahl clearly had a fascination for certain types of cruelty and vengeance. Here we see his interest in feeding things to animals which think they’re eating something else (e.g. the raisins and pheasants in Danny, The Champion Of The World.)

To shield readers slightly from the gruesome parts, and also to avoid the impression of a storyteller revelling in animal cruelty, Dahl has written a first person viewpoint character who mostly looks on (in disgust) as events play out between another guy called Claud and the ratcatcher.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE RATCATCHER”

SHORTCOMING

You probably already know the term which describes when things are compared to humans, and when animals are compared to humans. (Personification and anthropomorphism.) But do you know what we call imagery comparing humans to things? The term for that is far more esoteric.

Also in that post you’ll learn the term for imagery comparing humans to animals, which is what we have here: A man who has spent so much time with rats he is basically a rat himself.

(Note that Roald Dahl wrote another ratty-looking man in a different short story, “The Hitch-hiker“, suggesting a whole underclass of part-human, part-human characters in Dahl’s fictional version of England.)

In English we have idioms which speak to an early understanding of how environment forms character: If you lie down with dogs, you get up with fleas.

- Similar Chinese advice: 近朱者赤近墨者黑 (If you use a pen with black ink, you’ll be stained with black; if you use a pen with red ink, you’ll be stained with red.)

- From the Old Orient: Make a friend for 40 days and you will become like them. (The number forty comes up a lot when delving into djinn mythology.)

- Spanish: El que se acuesta con niños, amanece cargado. (He who goes to bed with children wakes up wet.)

- An Italian version is ridiculously ableist: Hang around with the lame, you start limping.

At first I assumed there had been some supernatural storyworld thing in which this guy is part man, part rat and he’d come to liberate the rats so they could all take over the humans, or something. But as the story progressed I changed my mind. It now seems that within the world of the story, this guy is monotropically focused on rats to the point where he must think like one. And once you think like someone, how are you any different from them? Who are we, if not the way we think?

This rat catcher considers rats very smart. He therefore considers himself very smart for being able to fool them. The trickster archetype is straight out of fairy tale, and Roald Dahl made heavy use of trickster plots.

ANOTHER HUMAN-MOUSE EXAMPLE

Here’s an example of a passage in which a narrator compares herself to a mouse:

When I think about people, I think about space, how much space a person takes up and how much use that person provides. I am just under five feet tall and just under a hundred pounds. Briefly I thought I would exceed five feet, and while that would’ve been fine, I also didn’t need the extra height. To stay just under something gives me a sense of comfort, as when it rains and I can open an umbrella over my head.

Today someone said that I looked like a mouse. Five six and 290 pounds, he, in a backless gown with nonslip tube socks, said that my looking like a mouse made him wary. He asked how old I was. What schools had I gone to, and were they prestigious? Then where were my degrees from these prestigious schools?

My degrees are large and framed, I said. I don’t carry them around.

While not a mouse, I do have prosaic features. My eyes, hooded and lashless. I have very thin eyebrows.

I told the man that he could try another hospital or come back at another time. But high chance that I would still be here and he would still think that I looked like a mouse.

the opening to Joan Is Okay, a 2023 novel by Weike Wang

DESIRE

Claud wants rats from the hayrick gone. The ratcatcher is clearly not driven by money. He is motivated by status. Comically, he earns status by being smarter than rats, and showing off to other men about his deep knowledge of how they work.

This very human tendency is easy to send up, because we all do it, and all of it is ridiculous.

If you think you don’t, look out for The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It by Will Storr.

What drives our political and moral beliefs? What makes us like some things and dislike others? What shapes how we behave, and misbehave, in groups? What makes you, you?

For centuries, philosophers and scholars have described human behaviour in terms of sex, power and money. In The Status Game, bestselling author Will Storr radically turns this thinking on its head by arguing that it is our irrepressible craving for status that ultimately defines who we are.

From the era of the hunter-gatherer to today, when we exist as workers in the globalised economy and citizens of online worlds, the need for status has always been wired into us.

A wealth of research shows that how much of it we possess dramatically affects not only our happiness and wellbeing but also our physical health – and without sufficient status, we become more ill, and live shorter lives. It’s an unconscious obsession that drives the best and worst of us: our innovation, arts and civilisation as well as our murders, wars and genocides. But why is status such an all-consuming prize? What happens if it’s taken away from us? And how can our unquenchable thirst for it explain cults, moral panics, conspiracy theories, the rise of social media and the ‘culture wars’ of today?

Or listen to this interview between Will Storr and David McRaney at the You Are Not So Smart podcast. The story of the guys with the massive yams is a real historical thing, and just as ridiculous as this ratcatcher showing off about rats.

OPPONENT

The rats are not the opponents. Claud and the narrator can either give the ratcatcher what he craves: Glory and masculine attention, or withdraw it.

PLAN

The dialogue in this story is fun to read aloud. When you do that, it’s clear how the ratcatcher has developed a spiel, saying over and over to every customer (and also over and over to the same customers) how you have to know rats if you want to catch them.

As part of his marketing spiel he has crafted some ridiculous tricks. Like an unexpected magician he is able to pull a rat and a ferret out of his pocket at any time.

Note that the magician is also an old storytelling archetype. But this guy is a wannabe magician. He’s actually a failed magician and also a failed trickster, as we will find out.

(The magician is another of the main fairy tale archetypes.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The ratcatcher considers himself a trickster, but in an unusual subversion, there wasn’t really any trick. Instead, the ratcatcher who considers himself really smart has shown himself to be gruesome, and also quite stupid, because he’s sacrificed his own dignity to win a bet on a shilling, reminiscent of a seven-year-old boy in a schoolyard.

ANAGNORISIS

Notice how Roald Dahl doesn’t tell us exactly what the ratcatcher did to the rat. We only know teeth were involved. We could say he mystery boxed it. But he’s utilising a much older technique from cosmic horror: What readers imagine is always worse than whatever is described.

The ratcatcher places the ferret and the rat inside his own shirt and readers imagine a gruesome but comical scene happening underneath the clothing. But more than that, the description of ‘two bulges’ and ‘shrieking’ underneath the shirt recalls unwelcome femininity. The ratcatcher, meaning to put on an impressive show, is inadvertently reminding the narrator and Claude of a woman. This makes him less worthy in the masculine hierarchy, and a comical figure.

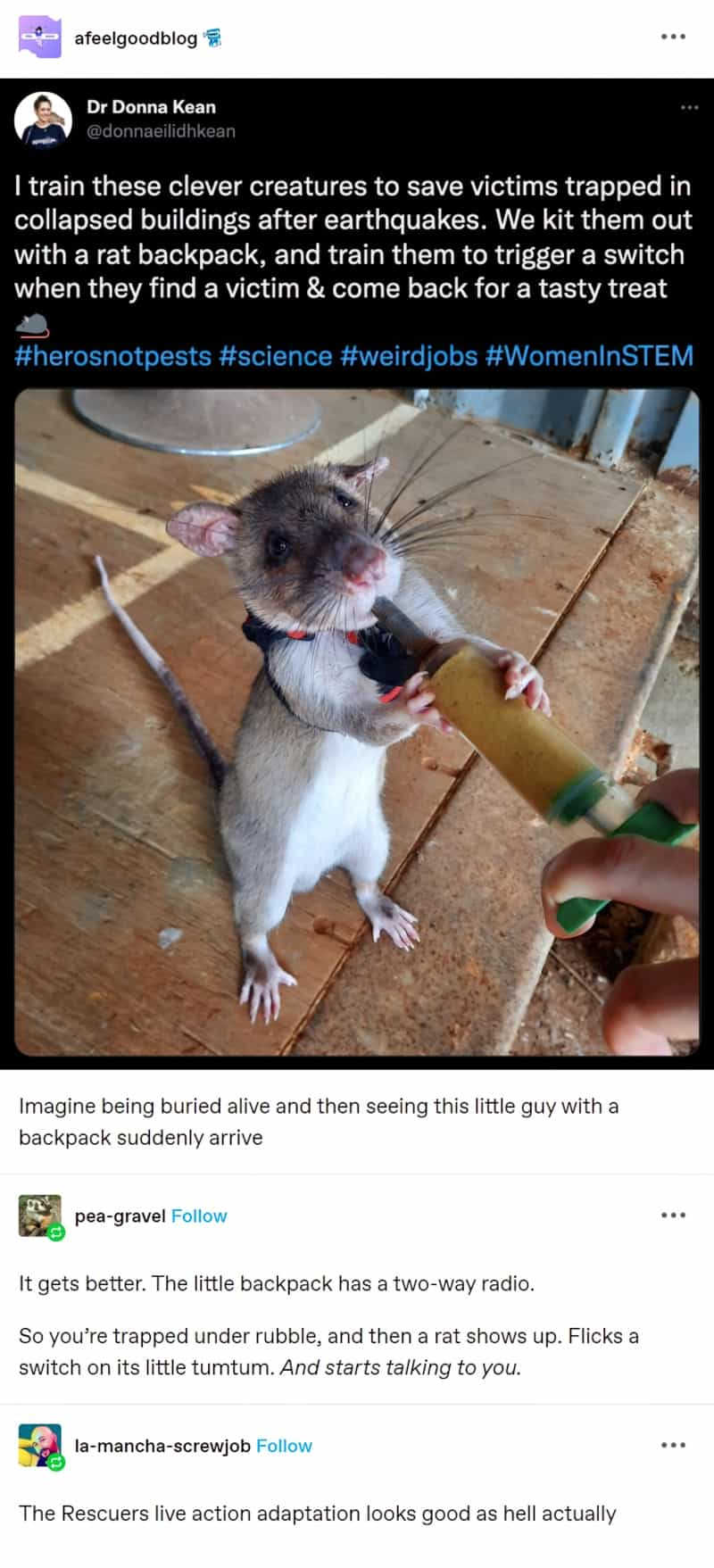

Come 2023, Wes Anderson adapted Dahl’s short story as a short film. Others in the series, with links to my analysis:

Anderson gets around the gruesome scenes by using a couple of film techniques.

First, he has his actor, Ralph Fiennes, use props which aren’t actually there. First the tub of poison isn’t real, next the rat and ferret in his pocket isn’t real. The sewer rat is a taxidermied-looking model which, metafictively, is presented to the actor in a box of props. But once it’s placed on a petrol pump, it becomes an animated rat, and the ratcatcher’s voice comes out of this animated rat.

This gets around a problem of film adaptation: While reading Dahl’s story, readers can imagine the ratcatcher looks part rat, part man. But Ralph Fiennes, despite his long fingernails and dishevelled costume, looks like a man. This filming trick also shows the audience how Claude and the narrator have been mesmerised by this (rat)man.

Now Wes Anderson uses a different technique to cloak the gruesome violence: The stage turns mostly dark.

Then we are shown a variety of different angles. We see the rat catcher as a different character entirely, smoking in a living room. Perhaps this was the ratcatcher before he got too close to the rats to the point where he became one himself. (After watching other shorts in the series, it becomes clear this is supposed to be Roald Dahl.) The image of the pre-ratified ratcatcher is interspersed with closeups on the faces of the characters in the present as the ratcatcher “strikes”. I find this especially discombobulating, perhaps, because I happen to think Rupert Friend looks like a younger version of Ralph Fiennes.

Because we’ve got a more reserved narrator, like us disgusted by these events, we feel he is legitimately holding back details to spare us.

More than that, I did not care to see. I closed my eyes, and when I opened them again, the rat was dead, and the rat man was slipping the money back into his pocket and spitting to clear his mouth.

“The Ratcatcher”

We can deduce he killed the rat by biting off its head. However, Dahl understood that (especially since leaving this scene off the page), the story would not feel quite finished if he left it there.

So Dahl gives the story relevance to everyday readers when his ratcatcher informs the audience that rat’s blood is used to make “lickerish”, which makes any enjoyer of liquorice no better than himself in the gruesome department. Likewise in The Witches, Dahl reminds us that we are surrounded by witches. In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, we are reminded that the story behind our consumed products are kept hidden behind the walls of factories.

But this is a bit of a shaggy dog story, because the ratcatcher simply isn’t as smart as he thinks he is, and isn’t able to shock and surprise the humans (including readers).

Enjoyment of this story comes instead from wondering what the eccentric fellow is about to pull next. And although I’ve never met such a man myself, his mien is absolutely familiar to me. There’s a strong tradition of tall tales and leg-pulling among boomer men here in Australia. If you journey to The Outback you’ll meet odd men who run their spiel on you, sitting back to see if you buy it, taking delight if you do.

NEW SITUATION

No doubt the ratcatcher will continue the same spiel into perpetuity. Where there are people there are rodents. It has always been so. The character of the ratcatcher has a repeating timelessness about him.

Dahl has left a major question unanswered: Why didn’t the rats eat the bait? Remember how this short story is one of an interlinked series about Claud’s Dog? Readers don’t get the answer until reading the story called “Rummins”.

tl;dr: In “Rummins” a character named Ole Jimmy dies. His body falls into the hayrick.

But Roald Dahl has put so much else into “The Ratcatcher” that readers almost forget about his uneaten bait. Alfred Hitchcock might have called this a MacGuffin. (In Psycho we forget about the money Marion Crane has stolen as soon as our attention is shifted onto the strange character of Norman Bates.)

RESONANCE

Three decades later, when writing The Witches (1983), Dahl returned to the topic of rodents and humans who become rodentlike. The boy captured mice — not for the purposes of cruelty, but to train them for a mouse circus. Dahl switched empathy from human to mouse in that children’s novel, and also relied heavily on nasty creatures who trick children by offering sweets which are no such thing.

But fear of food and its potential to alter your state has its outworkings in very old stories.

Take “The Juniper Tree“, a literary fairy tale about men’s fear of what their wives — with full control of the kitchen — might be doing to their food when they are not around to supervise and control. Until about a century ago, consumers were able to buy arsenic straight off the shelf. Arsenic happens to be a long, painful way to go, and was largely undetectable when added to food. (Of course, the poison was sold as ‘rat poison’, but it mostly comprised arsenic.)

I read all about this in the biography of Louisa Collins by Caroline Overington, the last woman hanged here in Australia.

Women around the world still bear the brunt of most household cooking, so the cishet masculine fear of poison-by-wife probably hasn’t gone away.

But for those living in wealthy countries without food insecurity, our fear of food is transferred away from the home cook to the corporation. We worry about sugar content, gluten and other contaminants making us ill if we don’t carefully read the back of packaging and reclaim the illusion of control. And even when we read the ingredients of modern food, we don’t understand what the words even mean.

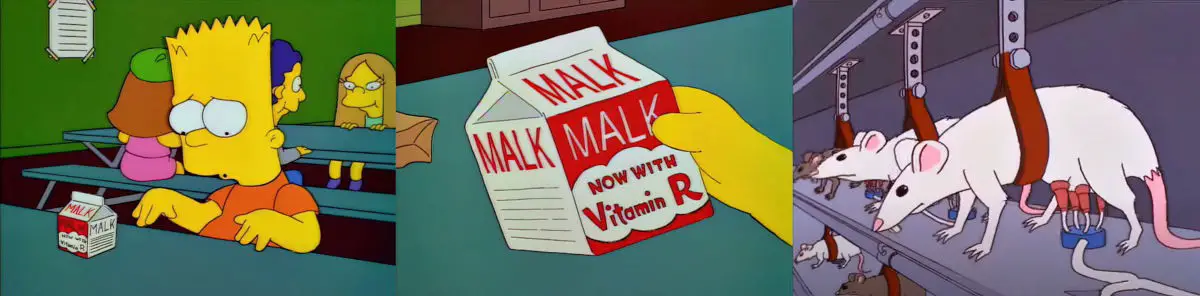

FEAR OF RATS IN THE SIMPSONS

The Simpsons parodied this specific fear with the ‘milk’ served as part of school lunches. Homer later discovers the ‘Vitamin R’ masks a terrible reality: milk is coming from rats.

THE MEANING OF RAT-CATCHER IN HUNTING LINGO

In fox hunting, costume has also assumed importance for a proper hunt. A “ratcatcher” refers to someone who is informally dressed, which would be frowned upon in good hunting circles.