“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is a 1977 short story by Roald Dahl, and the title of the collection containing seven stories altogether:

- “The Boy Who Talked With Animals”

- “The Hitch-Hiker“

- “The Mildenhall Treasure”

- “The Swan“

- “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”

- “Lucky Break”

- “A Piece of Cake”

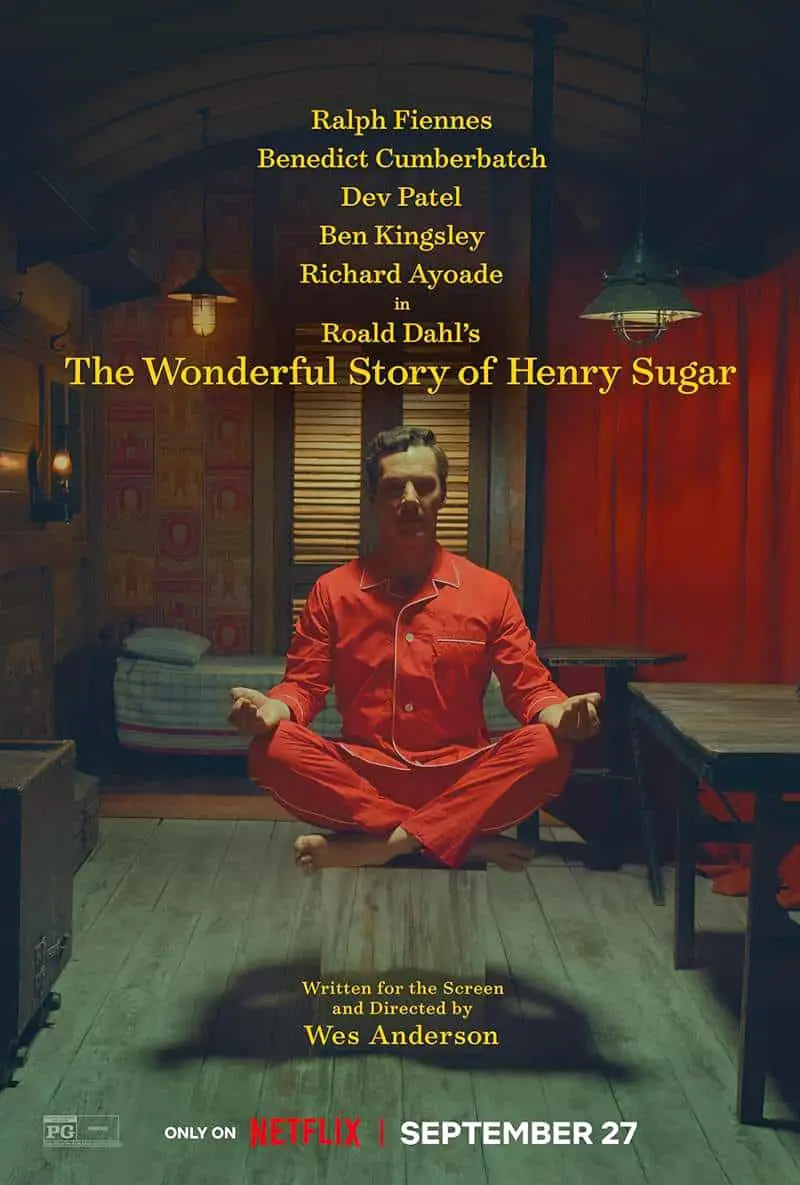

In 2023, Wes Anderson adapted several Roald Dahl stories for film. “Henry Sugar” was one of them.

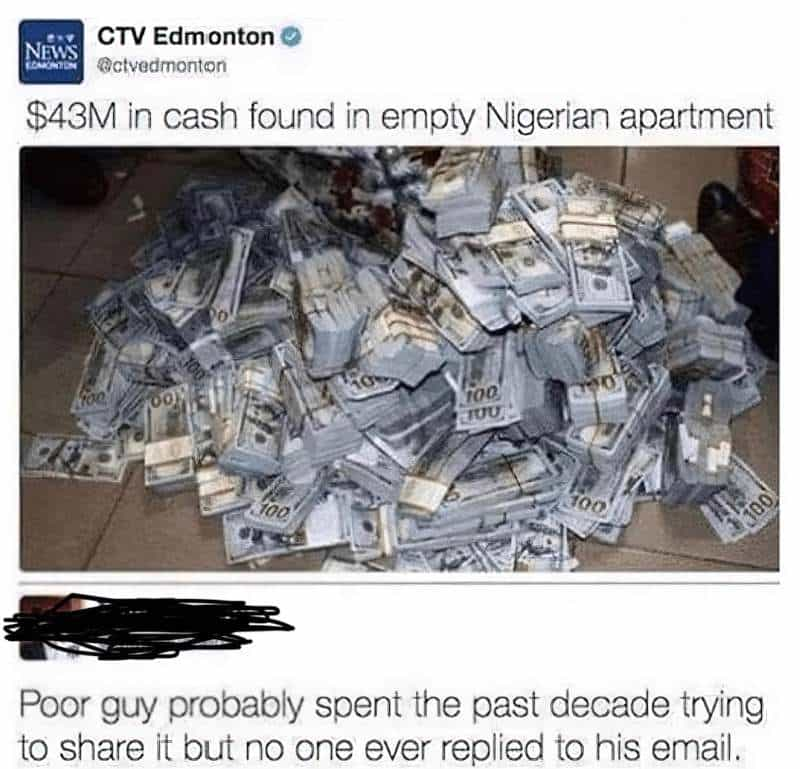

THE RESONANT IMAGERY OF “HENRY SUGAR”: MONEY SCRAMBLE

If you’re a fan of Breaking Bad you no doubt remember the scene where Jesse Pinkman has a moral crisis and throws wads of drug money out the car window while driving through a poor neighbourhood at night.

In Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away the creepy No Face character dispenses gold nuggets like irresistible treats, luring the greedy into the wrong moral path.

A well-known New Zealand short story by Booker Prize winning author Keri Hulme features a similarly resonant scene: In “King Bait“, townspeople scramble to catch as much whitebait as they can when a local river is inundated with the local delicacy.

WOULD YOU JOIN A MONEY SCRAMBLE?

A common truism: Everyone has a price. Would you join in this money scramble? Would you feel at all self-conscious about it? Obviously, there’s a socioeconomic reality here: Someone who is starving is trying to get their basic needs met.

I have vivid childhood memories of scrambling for lollies at Christmas events. In 1980s New Zealand, the lollies strewn around in scrambles were always RJ’s MacIntosh chewy caramels, which were one of the few sweets available in bulk. The different flavours all tasted pretty much the same, with the exception of the green flavour, which tasted the same but horrible for some reason. Probably because ‘mint’ and ‘caramel’ aren’t a great combo? (I see others on the Internet disagree.) The company is now owned by Allen’s and they’ve changed the design of the wrappers.

According to what I’ve read about the author, Roald Dahl himself was a renowned sweet tooth. His love of confectionary can be seen across various works, most notably in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

I wonder if Dahl ever enjoyed the lolly scramble tradition as a boy, and was thinking of lolly scrambles when he wrote the money scramble scene.

Even as a kid, I found lolly scrambles vaguely dehumanising. I was the kid inclined to stand back. As an adult, I wonder how easily I’d lose my inhibition if some dude was throwing cash from his balcony. Would I scramble for it? How mean would I get?

IF YOU CAME INTO BIG MONEY, WHO WOULD YOU TELL?

What proportion of your wealth would you donate to charity? What would you buy for yourself?

IS HENRY SUGAR BASED ON A TRUE STORY?

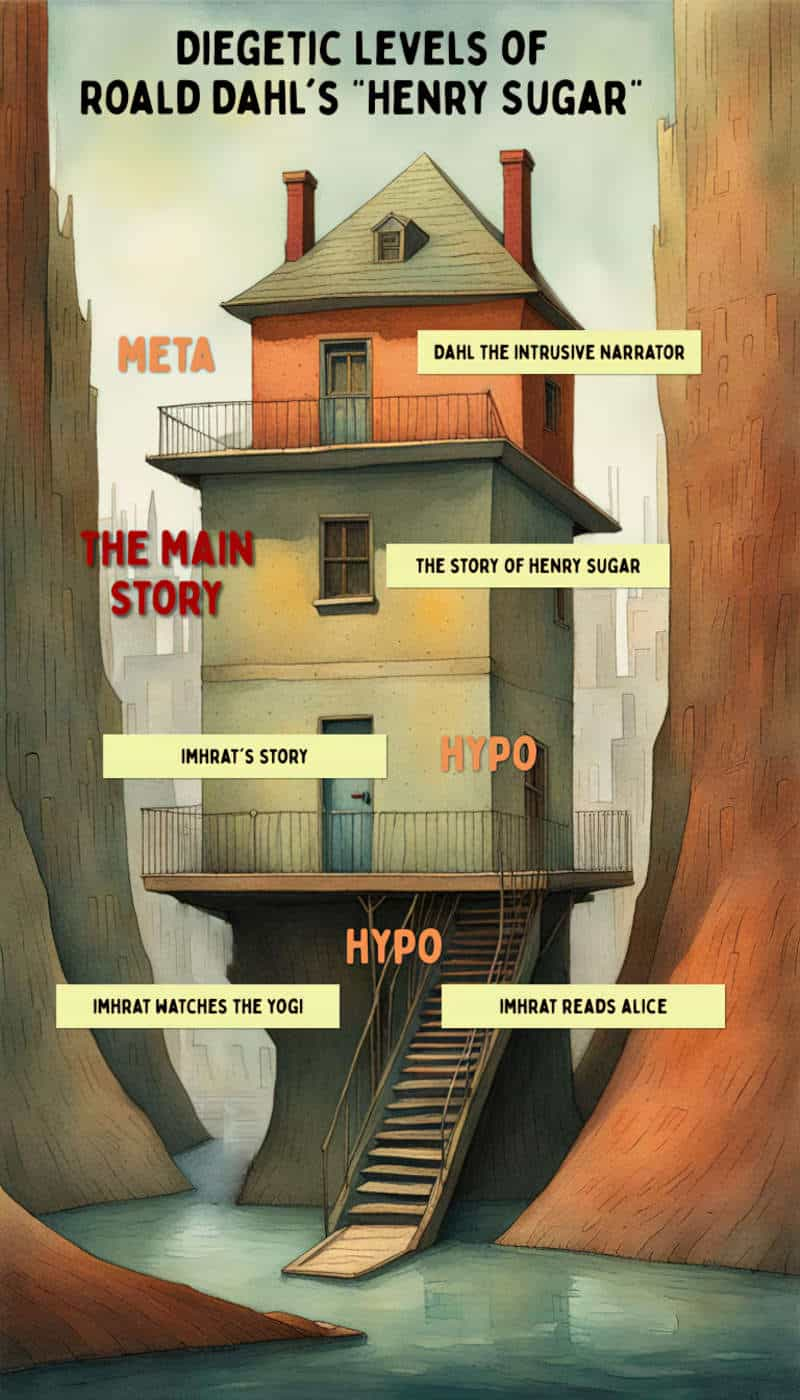

No. But using metafictive devices, Roald Dahl tries to persuade us the story is real. Persuasion is part of the tall tale tradition. Dahl goes further in this literary version of a tall tale by employing five different diegetic levels. (This is why a director like Wes Anderson is drawn to the story, I’m sure.)

It seems to me, it’s more common to Break Bad than Break Good in such a hyperbolic character arc as this one. Take media mogul Rupert Murdoch, arguably Australia’s most shameful export. The TV series Succession is heavily inspired by the Murdoch family. Believe it or not, Rupert had a go at being a leftie. As a student he was ‘the radical who espoused socialism’.

Walter Marsh recently published a biography of Rupert Murdoch called Young Rupert. Listen to the author speak about his book on Australia’s Late Night Live.

In September 1953, 22-year-old Rupert Murdoch landed in Adelaide, South Australia. Fresh from Oxford with a radical reputation, the young and brash son of Sir Keith Murdoch had arrived to fulfill his father’s dying wish: for Rupert to live a ‘useful altruistic and full life’ in the media.

For decades, Sir Keith had been a giant of the Australian press, but his final years were spent bitterly fending off rivals and would-be successors. When the dust settled on his father’s estate, Rupert was left with the Adelaide-based News Ltd and its afternoon paper The News — a minor player in a small, parochial city.

But even this inheritance was soon under siege, as the left-wing ‘Boy Publisher’ stared down his father’s old colleagues at the city’s paper of record, The Advertiser, and a conservative establishment kept in power by a decades-old gerrymander.

WHAT ARE DIEGETIC LEVELS OF NARRATIVE?

Imagine diegetic levels as a house. First we designate the ‘ground floor’. In this case it’s easy. It comes from the title. The ‘main story’ is “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”. Everything above that ground level main story is ‘meta’. This is where Roald Dahl the intrusive narrator jumps in. A metafictional level of a story reminds us that we are reading a story, perhaps by breaking the fourth wall.

Everything below the ground floor of the main story is ‘hypodiegetic’. In this case we have two underground levels. The first underground level is the story of Imhrat which Henry Sugar reads in a book inside a library at his friend’s house in Guildford.

Dahl doesn’t stop there. When Imhrat sits up a tree observing the yogi of Hardwar in the jungle, this hypodiegetic character is giving us yet another basement level. He is telling the story of the yogi. At one point Imhrat also refers to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. We’ll put that down there, too.

CLOSE READING OF ROALD DAHL’S SHORT STORY “HENRY SUGAR”

The story opens with the amatonormative notion that if you’re single and over 40 there must be something wrong with you. In this case, the thing wrong with Henry Sugar is selfishness and greed, one of the deadly sins.

Henry Sugar was forty-one years old and unmarried. He was also wealthy. He was wealthy because he had had a rich father who was now dead. He was unmarried because he was too selfish to share any of his money with a wife.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”

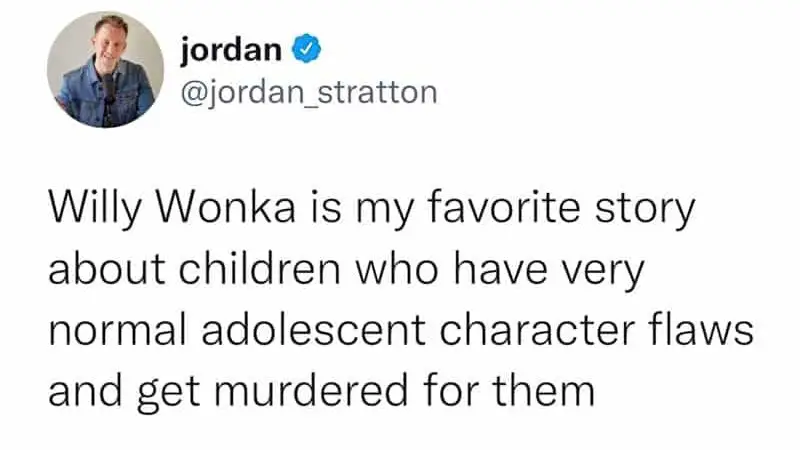

ROALD DAHL AND CHARACTER WEAKNESS

Roald Dahl was a fan of Deadly Sins as moral weakness. The baddies are obvious baddies with very obvious character flaws. Cf. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in which each child except our angel Charlie Bucket represents a deadly sin:

- Augustus Gloop – Gluttony

- Augustus is a constantly eating and overindulgent child. He drinks from the chocolate river and ultimately falls into it due to his insatiable desire for chocolate, illustrating his gluttony.

- Veruca Salt – Greed

- Veruca Salt demands her father to buy her a Golden Ticket and anything else she desires. She insists on owning an Oompa-Loompa and throws a tantrum when she doesn’t get what she wants, displaying her extreme greed.

- Violet Beauregarde – Pride

- Violet brags about her gum-chewing abilities and refuses to listen to advice, believing herself to be the best at everything. Her pride is evident when she insists on trying the experimental Three-Course Dinner Chewing Gum and subsequently turns into a blueberry.

- Mike Teavee – Sloth

- Example: Mike Teavee watches television and plays games constantly. He is not interested in anything else. He displays slothful behaviour by failing to engage with the world around him.

- Charlie Bucket – None

- Charlie is a humble and honest child throughout the story. He remains content with very little and shows kindness and gratitude, even when faced with difficult circumstances.

HENRY SUGAR’S DEADLY SINS

Henry Sugar is not only greedy like Augustus Gloop, but also prideful like Violet Beauregarde. Knowing that Roald Dahl as author took the most obvious and most widely-understood examples of wrongness, let’s take a close look at where the culture was at when Dahl wrote “Henry Sugar” in the 1970s.

He was six feet two inches tall, but he wasn’t really as good-looking as he thought he was.

It is still considered unattractive for someone to not know their exact ranking on the beauty of hierarchy. In men we see it as narcissism. In women we see it as both narcissism and also a little bit of crazy.

He paid a great deal of attention to his clothes. He went to an expensive tailor for his suits, to a shirtmaker for his shirts, and to a bootmaker for his shoes.

He used a costly aftershave lotion on his face, and he kept his hands soft with a cream that contained turtle oil.In the 1970s it was expected that women pay a great deal of attention to their clothes, though this has always been coded as frivolity. But a man? That would be evidence of failed masculinity, possibly homosexuality, and no doubt the mother’s fault.

His hairdresser trimmed his hair once every ten days, and he always took a manicure at the same time.

Talk to any Lebanese man in Sydney and he’ll say if you don’t visit the hairdresser every ten days are you even Lebanese?

His upper front teeth had been capped at incredible expense because the originals had had a rather nasty yellowish tinge. A small mole had been removed from his left cheek by a plastic surgeon.

Tooth culture has definitely changed. A few days ago I got an email from my local dentist which is clearly targeting women over 40 for Invisalign treatment. I quote: “Embrace Your Fabulous Forties, Fierce Fifties, and Sassy Sixties with Invisalign! Are you ready to rock your best smile game? Well, guess what? Age is just a number, and so is the time it takes to get your teeth aligned with Invisalign! So, fellow fabulous forties, fierce fifties, and sassy sixties, listen up because it’s time to give your pearly whites a reason to shine brighter than ever before.” Straight white teeth are now an expectation, not a sign of vanity but their opposite a sign of poverty and possibly drug addiction.

He drove a Ferrari car which must have cost him about the same as a country cottage. He lived in London in the summer, but as soon as the first frosts appeared in October, he was off to the West Indies or the South of France, where he stayed with friends. All his friends were wealthy from inherited money.

People who spend big on fast cars still come under scrutiny and are considered entitled drivers. The crime of owning such a car is worse if all of one’s capital has gone into it. Sensible people buy property, right? Not so much for the under 40s these days. Due to real estate prices, young people without inherited wealth may never afford a house of their own. Perhaps a nice car is the most luxurious thing they will ever own outright. Henry Sugar is presented as a sponger as well, though. Like real life Anna Sorokin, this character has surrounded himself with wealthy friends and does goodness knows what to keep them.

“Henry Sugar”

Dahl hasn’t finished with Henry yet. The author seems to really enjoy listing faults. Next we learn that Henry is slothful:

Henry had never done a day’s work in his life, and his personal motto, which he had invented himself, was this: It is better to incur a mild rebuke than to perform an onerous task. His friends thought this was hilarious.

“Henry Sugar”

Dahl the intrusive narrator (a technique, not an insult) steps in at this point and tells us what these men are like, as a class. Namely: They hang around big cities and ‘have a terrific urge to make themselves still wealthier than they already are’.

This aspect of wealthy people baffles the rest of it, I think. Those of us with limited means might think, “If I made a couple of hit records in the 1990s I’d buy a castle in Ireland and make like Enya. You’d never see me again.”

But the Enyas of this world are truly unusual. The vast majority of mega-wealthy individuals remain in the public eye. Elon Musk could’ve saved $44, bought himself a very nice island and we’d never have to hear from him again. He could vacation like Milton Waddams and kick back forever. I’ll never understand why he doesn’t just eff off.

Henry is a gambler and gets up to the sorts of tricks we see across Dahl’s body of work. Before a ridiculous race he forces a little sleeping-powder into the mouth of an opponent’s tortoise. This will probably put you in mind of Danny The Champion of the World, with the raisins and the pheasants.

THE SWITCH FROM ITERATIVE TO SINGULATIVE

Only once Roald Dahl is sure we all know the exact despicable archetype of Henry Sugar does he state that he’s beginning his story.

And now that you’ve got a rough idea of the sort of person Henry Sugar was, I can begin my story.

One summer weekend, Henry drove down from London to Guildford to stay with Sir William Wyndham.

“Henry Sugar”

This marks the switch from iterative to singulative time, and is a good example of an especially overt way of doing it.

TRIP TO GUILDFORD

At the Guildford manor the men cannot do anything fun because it is raining so they decide to play Canasta. But Canasta is a game for four, and Henry Sugar is left out. He wanders around the stately home until he comes to the library. Dahl criticises the character for only reading genre fiction and ignoring the canon of the day. This is a bit rich. Roald Dahl himself only ever wrote genre fiction.

Henry finds a slim hand-written volume on the shelf: A Report on and Interview with Imhrat Khan, the Man who Could See Without his Eyes (1934).

STORY WITHIN A STORY

Next, Dahl embarks upon a story within a story.

A named surgeon, John Cartwright, tells the story. With the guy’s name behind the testimony, we’re supposed to believe him. In truth, high education makes someone no less susceptible to conspiracy theories and general duping. In fact, many years of education can make someone more susceptible, because the best person to dupe is someone who thinks they’re too clever for it.

If any medical doctors are reading this, I wonder how often you sit around in the tea room all having ‘a well-earned break’ at the same time. That would be called a staff meeting. I guess these are slothful doctors.

The white doctors in Bombay are interrupted by an Indian man who annoys the doctors by being there. He would like to tell them he can see without using his eyes.

DESCRIBING THE SUPERPOWER

What superpower is this guy talking about, exactly? Let’s take a look at the options, straight out of speculative fiction, urban myth and legend:

- Second sight: a general term for the ability to perceive future or distant events.

- Precognition: the ability to perceive future events or information before they happen. Individuals with this power may experience visions, dreams, or intuitive flashes of insight that provide glimpses into the future. This ability can be both a gift and a curse, as it may come with the burden of knowing about potentially negative or tragic events.

- Clairvoyance: the ability to see things beyond normal perception, such as distant or hidden objects, people, or events. This power often involves extrasensory perception (ESP) and can manifest as remote viewing, where the individual can mentally “see” and describe a location or event they have never physically visited. Ray Bradbury makes use of this one in e.g. in “Homecoming” and “The Cistern“.

- Telepathy: involves the ability to transmit thoughts, emotions, or information directly from one person’s mind to another’s, without the need for verbal communication. Telepaths can also receive thoughts and feelings from others, creating a two-way mental connection. This power allows communication or the access to thoughts and memories of others.

- Psychometry: the ability to gather information about people or objects by touching them. When a person with psychometric abilities touches an object or person, they can receive insights, visions, or emotions related to the history or experiences associated with that object or individual.

- Remote Manipulation: Some superpowers allow individuals to manipulate objects or events from a distance. This might include telekinesis (moving objects with the power of the mind) or the ability to influence events or people from afar through thought or willpower. Dahl makes use of this one in Matilda.

EYES AND EVOLUTION

Dahl isn’t using any of these superpowers, exactly. The man cannot see into the future or into people’s soul. He can’t do any of that. Instead, he navigates the world like a seeing man even with his eyes bandaged shut. He is using another part of his body to see, e.g. his hand, so long as the skin is bare. As long as his hand can ‘see’ a book, he can read it.

This sounds fantastical, and it is, but reminds me of the feeling I get when I dip into evolution. At some point creatures had no eyes. Then, eventually, they did. That in-between part with the ‘photosensitive patches’ of skin, that fascinates me.

The first eyes appeared about 541 million years ago – at the very beginning of the Cambrian period when complex multicellular life really took off – in a group of now extinct animals called trilobites which looked a bit like large marine woodlice. Their eyes were compound, similar to those of modern insects.

Evolution of the Eye, New Scientist

For authenticity, the superpowered Indian — who earns his money displaying his superpower at a show — asks the doctors to authenticate him by making sure he couldn’t not possibly see. After testing him a little the doctors are intrigued and do as he asks, gluing his eyes shut, filling his eye-socket with dough, then finishing with bandages.

IMHRAT PROVES HIMSELF

The doctors clearly have no doctoring that needs doing, at least not urgently. If Henry was described as slothful, these surgeons are not. Yet they are shown to do about as much work as Henry.

They follow Imhrat around the city and watch in amazement as he navigates his world as if he can see. They attend his show and watch him thread a needle.

Imhrat is persuaded to tell the author/doctor how he does it.

THE STORY WITHIN THE STORY WITHIN THE STORY

Now Dahl takes us down another diegetic level and inside the house inside the slim book we hear Imhrat’s story.

Long story short, he wants to do real magic for fame and fortune. He finds a real Yogi in the jungle and from a nearby tree watches him levitate. The Yogi catches him and flies into a Rumpelstiltskin-like rage at having been seen. After that, the young magician returns to the spot and hustles until he gets a referral to another Yogi to receive instruction. He trains for three years.

He attends a fire-walking show, volunteers to fire-walk himself. Wants to put his mind-over-matter skills to the test. He successfully walks across hot coals without singing his feet, revealing himself as a yogi in training.

Next, he turns his attention to seeing without the eyes. His training involves staring at a lit candle with focus.

“All of us, you see, have two senses of sight, just as we have two senses of smell and taste and hearing. There is the outer sense, the highly developed one which we all use, and there is the inner one also.

WE CONTINUE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT HOW THE SENSES WORK

Scientists have since worked out that what we call ‘the sense of smell’ is indeed two different senses. (SARS-CoV-2 illuminated that for some people.) But it doesn’t work quite like this.

When it comes to how many senses are there, even just how many senses of smell are there. And actually, there are two.

And my favorite example of why smell is really interesting, also from a philosophical perspective, is when you would ask people, “How many sense of smell do you have?” They would look at you as if you’re a little bit crazy and say, “Well, one, of course. You’ve got one nose and you smell a smell.”

So what they personally thought. But actually it’s two.

So everything you call taste, when you taste something, or strawberry or mint or vanilla, etcetera, that is actually smell. And we know that because if you have a cold, you can’t smell it. You can’t smell and you can’t taste a thing. […] Even Immanuel Kant must have had colds and he still didn’t get the causality right. So you have a sense you don’t know you have.

Ann-Sophie Barwich on the Science and Philosophy of Smell, Sean Carroll

When Imhrat is asked to read from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to prove he can read using only his hand, this is Dahl taking us down yet another diegetic level. Now we have a story within a story within a story within a story. (Henry Sugar > The doctor’s book > Imhrat’s story > The story Imhrat reads.

DAHL’S HYPERBOLIC GRAMMAR: PARALLEL CONSTRUCTION

Back at the doctor’s level of the story, this author-surgeon gets excited.

We doctors must get hold of him and keep him safe. We must look after him. We mustn’t let him go. We must find out exactly how it is that an image can be sent to the brain without using the eyes.

“Henry Sugar”, and a good example of Dahl-esque parallel construction.

Here’s another example of parallel construction from later in the story:

I’m not an unattached bachelor like you with no responsibilities. I must talk to my wife and children. I must give notice to my partners in the firm. I must sell my house. I must find another house in Switzerland. I must take the kids out of school.

“Henry Sugar”

The doctors have big plans for the guy. But Imhrat takes off. The gatekeeper informs them that Imhrat died in his sleep.

Finally we’re back to the story of Henry Sugar, who I’d almost forgotten about. Henry immediately sees the application of this skill to cheating at cards. He could go to casinos and become rich! He takes the book to the butler, asks for a candle, finds a bedroom, shuts himself in, practises with the candle.

HENRY’S TURNING POINT: VANITY TURNS GOOD

The reader has already been told that one in a million people learn this stuff very quickly. Instead of visualising a loved-one, he visualises his own face. He loves his own image so much, and is so monotropically focused on the prospect of becoming rich, Henry Sugar’s a natural at this.

After just 10 months of practice, he is able to see an outline of objects with his eyes closed. He practises with playing cards. Eventually he is able to read cards from the reverse side very quickly.

THE LONDON CASINO

Henry is a member of ten London casinos already. He visits Lord’s House, which is not open to the general public. Once inside, Henry finds he now despises the wealthy patrons he used to admire. He also notices for the first time how all rich men have short legs. The women are blue-haired, fat, and dripping with jewels.

MONEY WORKS DIFFERENTLY FOR CONTEMPORARY READERS

I don’t understand Blackjack so the next few pages are intensely boring. To summarise, Henry wins £6,600 in all. We learn that this is enough to buy a small house or a large automobile. Ah, I long for the days when a small house cost about the same as a large automobile. The cheapest houses in London are currently in Thamesmead (SE28), where the median house price is £353,400. Thamesmead is a vast housing estate, with some peripheral industry, situated on former marshland between Woolwich and Erith. No shade to Thamesmead, but A Clockwork Orange was filmed there, due to requiring a “dismal dystopian” backdrop.

By comparison, a new Bentley Continental GT will set a Londoner back £186,160 to £273,360.

METAFICTIVE TECHNIQUE: SIDE-SHADOWING THE ENDING

Dahl goes full metafiction with his intrusive narrator and in an act of literary side-shadowing proposes a possible ending to the story:

So before telling you what really did happen to Henry in real life, let us pause here for a moment to see what a competent fiction writer would have done to wrap this story up. His notes would read something like this:

1 Henry must die. Like Imhrat Khan before him, he had violated the code of the yogi and had used his powers for personal gain.

2 It will be best if he dies in some unusual and interesting manner that will surprise the reader.

3 For example, he could go home to his flat and start counting his money and gloating over it. While doing this, he might suddenly begin to feel unwell. He has a pain in his chest.

4 He becomes frightened. He decides to go to bed immediately and rest. He takes off his clothes. He walks naked to the cupboard to get his pyjamas. He passes the full-length mirror that stands against the wall. He stops. He stares at the reflection of his naked self in the mirror. Automatically, from force of habit he begins to concentrate. And then. . .

5 All at once, he is “seeing through” his own skin. He “sees through” it in the same way that he “saw through” those playing-cards a while back. It is like an X-ray picture, only far better. An X-ray can see only the bones and the very dense areas. Henry can see everything. He sees his arteries and veins

with the blood pumping through him. He can see his liver, his kidneys, his intes-tines and he can see his heart beating.6 He looks at the place in his chest where the pain is coming from. . . and he sees. . . or thinks he sees. . . a small dark lump inside the big vein leading into the heart on the right-hand side. What could a small dark lump be doing inside the vein? It must be a blockage of some kind. It must be a clot. A blood-clot!

7 At first, the clot seems to be stationary. Then it moves. The movement is very slight, no more than a millimetre or two. The blood inside the vein is pumping up behind the clot and pushing past it and the clot moves again. It jerks forward about half an inch. This time, up the vein, towards the heart. Henry watches in terror. He knows, as almost everyone else in the world knows, that a blood-clot which has broken free and is travelling in a vein will ultimately reach the heart. If the clot is a large one, it will stick in the heart and you will prob-ably die. . .

That wouldn’t be such a bad ending for a work of fiction, but this story is not fiction. It is true.

The

“Henry Sugar”

only untrue things about it are Henry’s name and the name of the gambling casino. Henry’s name was not Henry Sugar. His name has to be protected.

Dahl tells us what “actually” happens.

NOW FOR THE ‘REAL’ STORY

Filled with melancholy where he expected happiness, he learns a valuable lesson: Nothing is any fun if you can get as much of it as you want. Most of us know this lesson instinctively.

THE MORAL LESSON

Below, a retirement expert reminds us all that the process of acquisition is more fun than the acquisition itself, so take time to plan your holiday. Research your purchases. The act of planning and research is a large part of the reward.

How we shop has a greater effect on our happiness than what we buy.

Emily Guy Birken is an award-winning writer, author, money coach, and retirement expert.

She tells us how to get more bliss for our buck.

Emily Guy Birken: How to buy happiness

But Henry Sugar goes further. The money starts to disgust him.

THE MONEY SCRAMBLE SCENE

So he throws it one note at a time over his Mayfair balcony into the street below. This causes chaos on Curzon Street. This is a real place, geolocatable. This helps readers to feel this might really be a true story.

Henry causes further chaos by chucking the remaining 6000 pounds into the street all at once. This upsets a storybook policeman.

THE RANGE OF CHARACTER CHANGE IN STORYTELLING

In any story, main characters undergo a character arc. (In sit-coms, the characters are reset between episodes.) The questions is, how much must characters change before we can call it a character arc?

In a Roald Dahl story hyperbole is applied to the range of character change. Henry Sugar goes from being a greedy, selfish, lazy young man to a full on hard-working philanthropist. He employs his accountant and a make-up artist to work for him. (The make-up artist allows him to keep travelling between casinos anonymously.) He uses the proceeds to build orphanages all around the world, including the one Sophie lives in at the start of the B.F.G., I assume. (Dahl was a fan of Dickens — his worlds are part mid 20th century, part Victorian.)

Eventually Henry Sugar dies, after spending the rest of his life cheating at casinos and donating the profits.

BACK TO THE NARRATOR’S STORY

Now the diegetic level changes again, but in the opposite direction. Instead of delving deeper into a story within a story, we are pulled out of the story, up to the meta level. The intrusive narrator tells us a little about himself.

Soon after Henry’s death, John Winston telephoned me from Switzerland…

“Henry Sugar”

The narrator is a Roald Dahl stand-in, a writer, who is now contracted to tell the life story of this anonymous Henry Sugar. Max Engleman, the make-up artist, expresses his love for the late Henry Sugar. Max has plans to write the life-story himself, except according to the accountant he only wants to write the parts of the story about Henry and Max together.

Contemporary readers will now understand the real reason why Henry Sugar never married a woman.

Dahl wrote a gay love story*. I would have preferred to read that.

Max had been beside him constantly for over thirteen years. “I loved him,” Max said, a shadow falling

over his face.

*”Does every male friendship have to be a gay love story?” No. We need more stories about male friendship.

Is “Henry Sugar” a gay love story? I don’t care, yes.