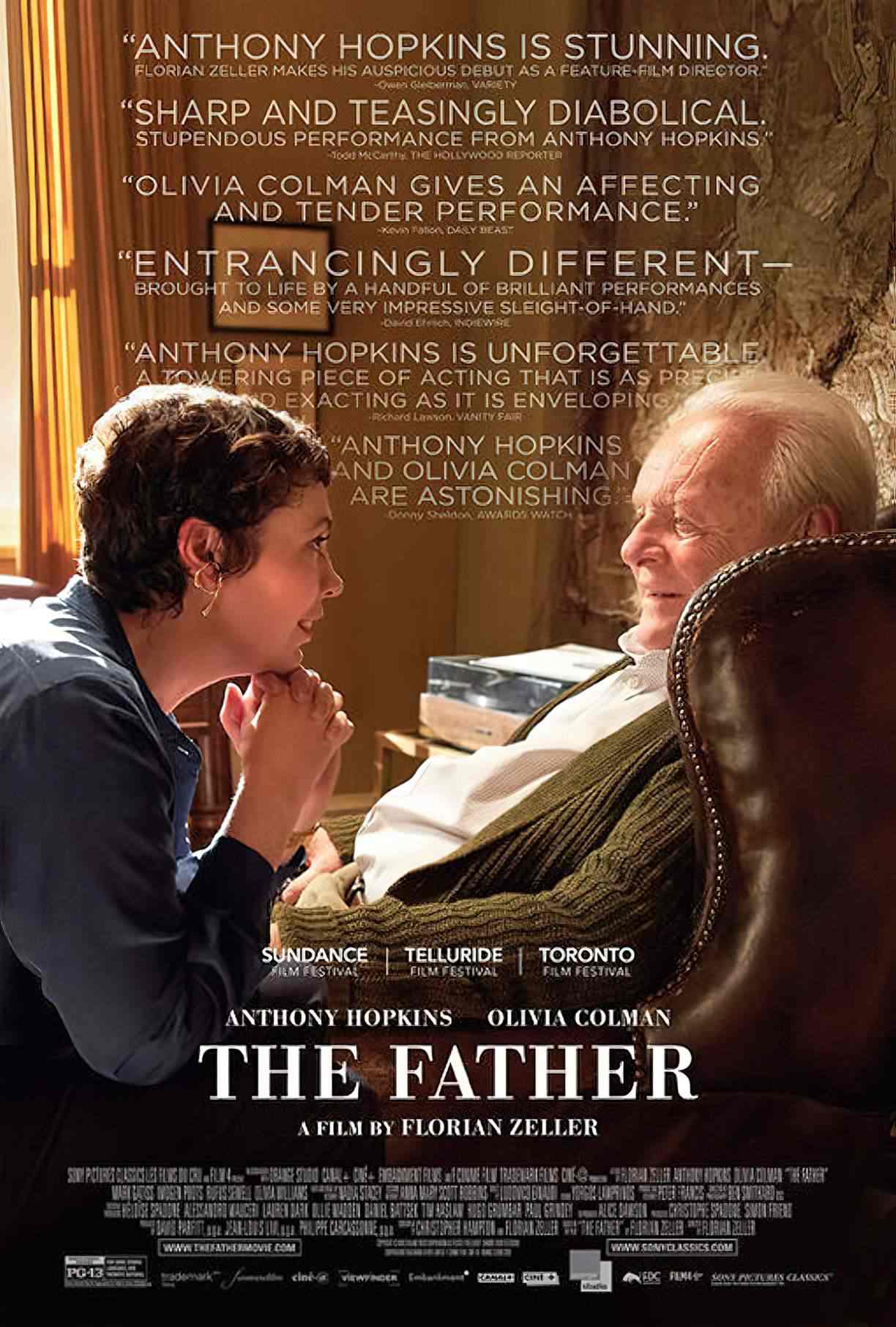

The Father is a 2020 film written by French playwright Florian Zeller, translated (and co-written) by Christopher Hampton. The film was a French stage play first, but as Florian Zeller says in interviews, you wouldn’t recognise the film and stage play are the same story.

BOOKS ARE NOT ALWAYS BETTER THAN FILM

It’s cliched to say that “The book is always better than the film.” But next time someone says that, mention The Father. There is no book, but if there were, the book would lose a massive part of what makes this film (and stage play) work so well: Different characters played by the same actors. No other notes needed. This fictional treatment of dementia is the closest I have experienced to actually having dementia. I’ve seen — or read — nothing like it.

Film also allows tricks unavailable to stage directors. For example, Florian Zeller wasn’t able to break audience logic with juxtaposition to nearly the same extent compared to when he adapted it later for film. In the film, they were able to make it seem objects were disappearing into the emptiness: Now you see it, now you don’t. As a play, this was treated as an abstraction. But with movies, abstraction is no longer possible. A backdrop must exist. No hand-waving is possible.

That said, if you’d like another great story about dementia, check out Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over The Mountain“. That short story was also adapted for film, but in contrast to The Father, works better written down, because of the interiority.

(Twilight and Bridges of Madison County also work better as films, but, ah, that’s only because the writing gets in the way.)

PARATEXT

A man refuses all assistance from his daughter as he ages. As he tries to make sense of his changing circumstances, he begins to doubt his loved ones, his own mind and even the fabric of his reality.

logline of The Father

This film affected me very deeply. Yet it’s difficult persuading people to watch The Father. Dementia affects us all — either because we’ve seen it in friends and family or because looms in everyone’s possible future. While I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone deep in the weeds of dementia (whether personally affected, or affected as carer) for everyone else, I’d recommend The Father as a cross between Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) and Michael Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

I have also heard The Father compared to Relic (2020), partly because they came out the same year and were in the running for the same awards, and partly because both films are about dementia:

A daughter, mother and grandmother are haunted by a manifestation of dementia that consumes their family’s home.

logline of Relic

Zeller himself points to his use of features from psychological horror. I’d like the term ‘spatial horror‘ to become more widely used, because this film is an excellent example of it. In spatial horror we don’t know where we are, or how to get out. Sometimes we feel like we’re falling, or being sucked into a vorfex.

Zeller uses the word labyrinth. Here’s the thing about a labyrinth: There’s a Minotaur (death) at the centre.

THE SHAPE OF THE PLOT

Speaking of vortices and labyrinths, the overarching shape of this plot is ‘vortex’. (Sometimes called a Whirlpool or Tornado Plot.) There is also judicious use of repetition. Every day for Anthony starts to look the same. But further than that, when time folds into itself, an item in the kitchen today equals the same item from a time in the past. Life begins to feel even more repetitive than it is.

Hear the director talk about how they conveyed time confusion in conversation with Jeff Goldsmith at The Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith podcast.

THE OFF-KILTER REPETITION OF THE FATHER

- Audiences, like Anthony, are not supposed to know how many chicken dinners happen in the story. Is this various chicken dinners, or just the one?

- Repetition in the lines (writing):

- Repetition in the directing: Five instances of the same frame, but not the same characters or actions within it.

- Repetition in the setting: The same corridor over and over. Audiences become very familiar with it. But whenever the corridor leads into a door, we don’t know what we’ll find on the other side. Whose house? A doctor’s surgery? Finally, most disturbingly, a cupboard which takes Anthony back to the most traumatic time of his life, opening into a hospital.

Notice how the film-makers have utilised that uncanny trick where repetitions are not exactly the same. This is unsettling because we can’t tell if this is déjà vu, or if we are hearing two different instances of something, or just the one, in a prison-like spiral.

Likewise, visual artists create an unsettling feeling in audiences when creating not-quite-symmetrical symmetry. Any kind of not-quite-repetition engenders discomfort.

THE DOORS AND CORRIDORS OF THE FATHER

Corridors are an established horror space.

They can’t really be separated from doors, all part of the same terrifying liminal space between sensible and senile.

Painters frequently utilise doorways as frames-within-frames. The work below, by Felix Vallotton, has an ominous quality you’ll also find in The Father: Straight lines, partial, peephole views, visible shadows of things not seen. This is the classic mise en abyme effect, one of the tools in spatial horror box.

ANTHONY HOPKINS AS “ANTHONY”

When Zeller started writing the film for an English speaking audience, he already had Anthony Hopkins in mind. But this only partly explains why the character and actor are both called Anthony. Zeller didn’t want Anthony Hopkins to act. He didn’t want him to be protected by the fiction of the character, and needed the characterisation to come from a very personal place. Sure enough, this worked. At the climactic scene, Anthony Hopkins imagined his childhood self, listening to a lullaby sung by his own mother.

Hopkins himself quipped during filming that he’s glad he no longer needs bother with ‘old man acting’. Born in 1937, he is an actual old man these days.

As I get older, I can cry at the drop of a hat because the wonderful, terrible passion of life is so short. I have to believe there’s something bigger than me. I’m just a microbe. That, for me, is the biggest feeling of relief – acknowledging that I am really nothing. I’m compelled to say, whoever’s running the show, thank you very much.

Anthony Hopkins, January 2020

(By coincidence, both actors who play Anne — or possibly Anne — happen to be called Olivia.)

SETTING OF THE FATHER

PERIOD

Contemporary ~2020

DURATION

Ah, now duration is the most fascinating aspect of this film. We don’t know! And the filmmakers make sure we’re fine with that!

Hence the watch motif. As the film progresses, we develop increasing empathy for Anthony’s need to know where his wristwatch is at all times, and his fear of having it stolen. He has lost grip on the passing of time. For him, it really does feel as if someone is stealing time from him.

Three possibilities exist for the passing of time in The Father:

- The entire story takes place in Anthony’s head, perhaps as he’s sitting at the window listening to his music. In this case, the telling of the story (97 minutes of screen time) maps onto how it plays out in Anthony’s head. The narratology word for this is ‘isometric‘.

- The story plays out over two days. This would mean the scenes in Anthony’s house took place in the past. The story would begin (for audiences) with Anthony in his daughter’s house, about to be moved into the care facility. He wakes up the following morning in the care facility and doesn’t know where he is. In this interpretation, there is only one chicken dinner.

- The story plays out over three months. According to the film-makers, Anthony may have lived for three months with his daughter.

- Years? As I was watching, I considered whether this story took place over years. Perhaps five or six years. In this scenario, Anthony moved in with Anne. This led to the breakdown of her marriage. Against her husband’s wishes, Anne refused to put her cantankerous father in a care facility. After the husband left, her father became worse. Over time, Anne met another man, who happens to live in France. Eventually she understood her own life is also short. She makes the decision to leave her father, guided by the harsh reality that he no longer recognises her. If France and England are the same to him, she may as well be in France.

Around the world, languages differ in how specific they require speakers to be when conveying an idea.

Why does English make us specify whether a thing happened now or in the past?

So, in Chinese for example you don’t have to specify the time in a statement. You can say the time but don’t have to say it, which is one of the parameters in which language varies.

Lingthusiasm podcast, Episode 72: What if?

We can say this of stories, too: Concreteness of time is one of the parameters in which stories vary.

Narratologists have various ways of talking about this variation. But I especially like the distinction between mythos and chronos. Chronos refers to the very recognisable, workaday, linear experience of time. But mythic time takes us into the subconscious, where memory co-exists with the reality of now and also possibilities for the future. Fairytales work with mythos, and so do some of the most interesting contemporary stories. Mythos “breaks logic with time and space”, as Zeller himself describes.

As demonstrated in The Father, mythic time (in which past, present and future fold in on themselves) is especially good for dealing with mental conditions such as dementia. (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind also sends us into the subconscious, where time no longer feels linear.)

The set design was not about providing a background for the characters. It was…about telling the story. In the script it was written like: Apartment One, Living Room One, Bedroom One. And then: Apartment Two, Living Room Two, Bedroom Two. So we knew the change had to be obvious. But how obvious was a delicate balance. It was something that I had to define later on during the preparation of the film. We defined some steps in the evolution of that apartment from Anthony’s apartment to this empty space that was supposed to be the hospital.

Florian Zeller talking to Jeff Goldsmith

LOCATION

Mostly in two London flats which are positioned nearby, as Anthony’s daughter has decided to live round the corner.

The set designer did a masterful job of confusing audiences to the extent Anthony himself is confused by his shift from his own flat to that of his daughter. Tricks were used:

Object Permanence

Audiences like to see the same item crop up time and again. We feel the world is more real that way. (The term ‘object permanence’ comes from psychology but is useful in storytelling.)

The Father makes use of the same blue plastic bag(s). We first see these bags in his own kitchen at the beginning of the film. 15 minutes later, we see a new apartment with a new kitchen. But the plastic bags seem to be the same. Anne puts the plastic bags down in exactly the same position. So it appears that this is a flashback. We are seeing when the bags arrived and how they got there. (Anne put them there.) However, this is not the same apartment. The audience can deduce Anthony moved from his own apartment into his daughter’s, not the other way around. Ergo, although these seem like the very same bags, they are different bags — identically coloured — and by coincidence positioned the same way (because of the angle of the camera, of course). This is how the filming and editing messes with our own sense of time and space.

Keen-eyed viewers may have wondered if the filmmakers messed up when Olivia Colman re-enters a room wearing a different shirt. Of course, ‘continuity errors’ are entirely deliberate. The experience of living with dementia is one long continuity error.

COLOUR: METAMORPHOSIS FROM GREEN TO BLUE

I started with the end. I knew we had to lead to this hospital corridor and in my mind it was a pale blue corridor. The pale blue was the destination, visually. So we started with a green and yellow apartment. … We needed a strong atmosphere so the audience would identify this space as Anthony’s. When filmmakers contrive a transformation or a metamorphosis, it works on the audience.

Then we had to introduce the idea of blue. This was done through Olivia’s shirt, through the plastic bag and so on. Step-by-step, the blue occupied more and more space, becoming a bluish atmosphere, and finally a blue hospital.

Florian Zeller talking to Jeff Goldsmith (edited for clarity)

A SENSE OF SUBJECTIVE UNREALITY

Florian Zeller pushed back on the temptation to use the camera to underscore for the audience “this isn’t real, this is just happening inside his head…”

Instead, filmmakers went with a completely realistic aesthetic. This absolutely contributes to the horror.

Everything is shot as if it was reality. And when you have a strong contradiction in the narrative you have to deal with it. Suddenly you have to play with all the pieces and try to make it… meaningful, to look for the correct combination.

Florian Zeller talking to Jeff Goldsmith

The audience is supposed to be asking questions such as:

- Who is this character?

- Is he real?

- Is he lying?

This shortens the distance between narrator and narratee, bringing the audience inside the narrative. When shooting a film, camera distance is also crucial. The audience should feel as if we are in the room with the characters, sitting on the vacant chair, sitting with them at the table, peering into a room from behind a door.

SURPRISE

It’s always very enjoyable, finding ways of giving people what they don’t expect.

Christopher Hampton, speaking to Jeff Goldsmith

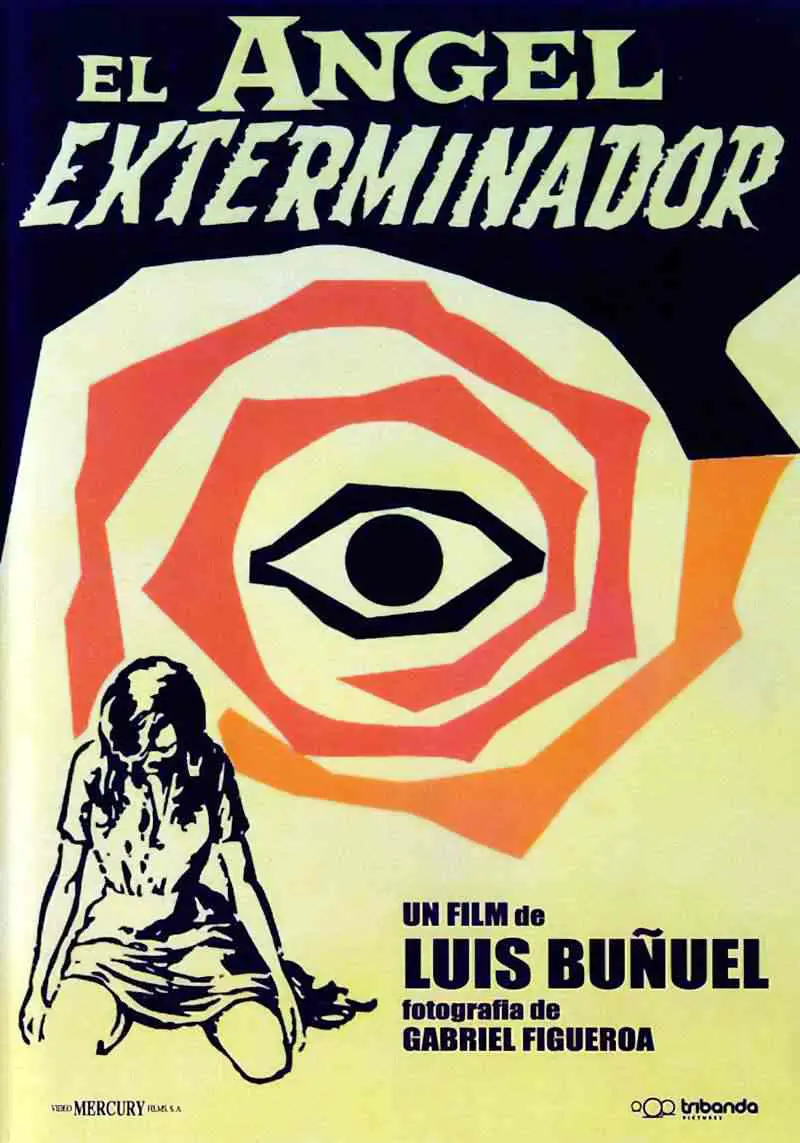

Christopher Hampton offers the excellent example from 1962 Mexican surrealist film The Exterminating Angel. All the audience knows: There are people at a party and no one can leave the room. There’s no reason why. The door is clearly open. (An early example of Mystery Boxing?)

Similarly, in The Father, the filmmakers were telling the audience: “We can’t leave this poor man’s head. Anything might happen because it’s degenerating in unforeseen and painful ways. We’re just going to say: This happens, this happens and this happens. Figure it out.”

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The wrist watch is a very obvious (but very effective) symbol of ‘losing time’ and is also a slightly outdated thing, showing us how Anthony is stuck in the previous century, when wrist watches tended to be valuable. Some still are, of course, but fears about someone stealing your watch are on the same mythic level as servants stealing the silver. (Thieves aren’t interested in your cutlery.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE FATHER

Because the setting is so complicated, the story itself is simple. Though it is very difficult to manage the experience of disorientation in a story which exists in the space of mythos, there is one huge advantage: No exposition is needed. (Because Anthony can’t remember it.)

As translator and co-writer Christopher Hampton explains:

Exposition is the beast that sits on your shoulder every time. You’re really straining always to try to make it invisible. And here that wasn’t really necessary because it was an exposition-less story by design. Rather than opening it out as you normally do from a play to a film, we were closing it down.

Christopher Hampton talking with Jeff Goldsmith

DEGENERATION AT MULTIPLE STORY LEVELS

The story as a whole entity is about degeneration. Degeneration can also be witnessed at a scene level. For instance, when he meets his carer, Anthony puts on a good face. But the scene declines into a terrible experience for all involved. You’ll see this pattern in other scenes: The micro mapping onto the macro, all leading towards degeneration.

SHORTCOMING

Anthony has dementia but is not willing to accept his new situation. He pushes back by refusing help.

DESIRE

He wants to retain independence, which is another way of saying he wants to avoid the descent into death.

OPPONENT

Anne, his daughter, may or may not be moving to France. She must hire a carer. Unless Anthony accepts home help, he will be rehomed into an aged care facility.

A mystery is set up near the beginning which serves the story-within-a-story: What has happened to Anthony’s other daughter? Was there even another daughter, or is Anthony recreating a better version of Anne? Did something terrible happen, or has she cut ties with him?

PLAN

Anthony doesn’t know which house he’s in or who anyone is. Plans are made around him.

We never know for sure that Anne has gone to France. Anthony is inclined to make up fanciful things (e.g. we’ve seen him tell the home carer he used to be a tap dancer). Moving to France with a new man might be another invention from Anthony’s addled mind, since France, for everyone not living in France, is a Romantic, fairytale place where people go (and sometimes don’t come back).

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The story switches point of view (or seems to), opening by getting the audience on side with Anne, who is dealing with a difficult — and at times hilarious — father. But when the new ‘Anne’ turns up (billed as The Woman), suddenly we are in Anthony’s head. This moment is terrifying. It’s even more terrifying than Anthony finding a stranger in ‘his’ home (which is not his home at all, but his daughter’s).

In Anne’s head — or perhaps in Anthony’s imagination — Anne imagines strangling her father as he sleeps.

With Anne out of the room, Anthony’s son-in-law may or may not physically abuse him.

Spatial horror continues until the climactic scene when Anthony is in an aged-care facility, trying to work out where he is and who everyone is.

THE STORY-WITHIN-A-STORY: THE DEATH OF ANTHONY’S DAUGHTER

One of the most horrifying parts of this film: The idea that even when you’ve lost your ability to know who loved-ones are, and which house you’re in, you don’t lose your PTSD. Anthony gets up one night, opens the closet and enters a terrifying memory from decades ago: his other daughter after an accident. The audience is let in on the fact that she died, but Anthony himself vacillates between thinking her still alive, and revisiting the moments around her death, in some hellish, Sisyphean cycle of denial and fresh realisation.

ANAGNORISIS

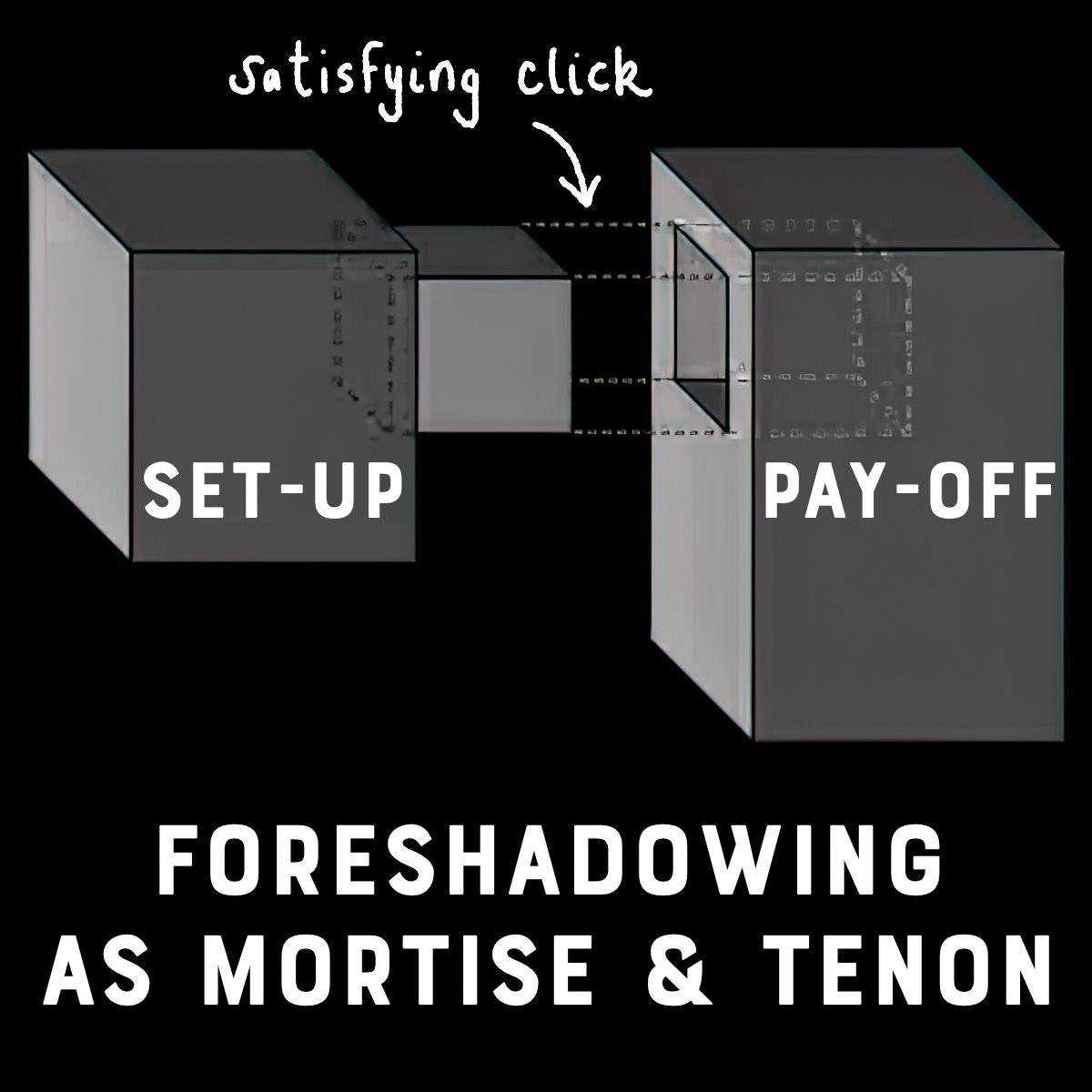

THE SLAP AS MORTISE AND TENON

We never know if Anne’s husband really slaps Anthony, but the reality of elder abuse in the real world will affect our reading of the ending. The male nurse (“The Man”, conflated with Anne’s husband) may be abusing him. We realise this when we see the nurse at the home (sometimes) played by the same actor as the son-in-law.

To understand that scene [of the slap] we have to go to the end of the film, to the hospital, and suddenly we see Mark Gatiss — the actor — coming into that room as another nurse. Suddenly we understand this man, who was like a stranger, in Anthony’s apartment, and turned into this vile man slapping him, was in fact the nurse. So it was just maybe about when you are in hospital in this condition you could become paranoid. So many times, people alone in hospital with dementia, they have so many fears about being mistreated. You have to wait until the very end to understand, “This is probably what happened.” Meaning the whole story was told, in a way, from that perspective.

Florian Zeller

This is a classic case of delayed decoding.

It is also an example of mortise and tenon coming together (or set-up and pay off). Stories need some kind of clicking together at the end before audiences feel a story has concluded in a satisfying way.

But what I find fascinating about this particular example, of ‘slap as mortise and tenon’: The audience experiences emotional closure but not hermeneutic closure. (The emotional part is tidied up, but we never know exactly what happened.)

You’re much more likely to find this sort of ending in short stories, which are famous for it. Such stories require more effort from the reader/audience, and an audience is brought more fully into the story. For those who do make the effort, the reward is enormous.

NEW SITUATION

When the camera pans out to the trees and above to the sky, anyone who has ever seen a film in their life will recognise this symbolism: Death comes next for Anthony. Death is the only way he’s getting out of here.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Of course, it’s not just dementia patients who are having time stolen from them. We all are. Life is a thief of time, no going back.

*shudder*

RESONANCE

Funnily enough, audiences actually crave content that reminds us life is short. Any story that does this — however sad in the moment — functions as a form of catharsis, letting us get back to our regular lives with a little more gratitude for being alive.

We also like content which challenges our assumptions.

One thing to be careful of when either writing or interpreting stories (and conversations) about dementia: The tragedy of dementia is not measured by the distance of the descent. Meaning this: Anthony’s decline is no more tragic simply because he was a talented engineer, useful to society. To lose one’s mind is always a tragedy, and human life cannot be ranked.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

For me, many of the most interesting films began as a stage play. Other favourites:

Jeff Goldsmith interviews Florian Zeller and Christopher Hampton at his podcast The Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith (18 April 2021). If you only want the storytelling stuff without all the Hollywood-ish actor stuff, they start talking about storytelling aspects (including spoilers) after 42:25 minutes.