The success of a novel is only five percent about the structure and ninety-five percent about the quality of the writing.

Elizabeth Lyons, Manuscript Makeover

Younger writers should be experimenting with form as well as material, like a water-seeker with a divining rod. We are “haunted” by experiences, images, people, acts of our own or of others, which we don’t fully understand and the serious writer approaches such material reverently.

Joyce Carol Oates

Idea: closed captions for the film-illiterate & face blind

@mckinleaf on Twitter

[This is a dream sequence]

[This is a flashback]

[This is the main character as a kid]

[We’re back in the present now]

[This is the same woman from the cafe scene]

[You’re not supposed to know who this guy is yet]

Plots that revel in complexity often end in simplicity, as many Victorian plots do. Honore de Balzac’s forays into the intrigues of Parisian society, for example, place so much pressure on his plots and themes, such a dizzying excess of possibility, that he reacts by retrenching in “drastic simplification.”

Brief Encounters: Street Scenes in Gaskell’s Manchester, Sue Zembka, ELH Vol. 76, No. 3 (Fall, 2009), pp. 793-819

THE LINEAR STORY

The linear story is a traditionally Western story.

Linear Plots In Adult Film

As the main character experiences a character arc, the audience is along for the ride. In the best linear stories, the audience experiences some kind of revelation alongside the main character. The majority of films coming out of Hollywood are linear in shape. This is the O.G. plot shape. It goes back a very long way.

Linear Plots In Children’s Stories

As in film, the majority of children’s stories are basically linear. However, the plot doesn’t necessarily begin where the story begins. Home-away-home adventure stories are generally linear.

Dennis Butts, among others, has pointed out that in their use of formulaic elements and stereotyped characters, adventure stories owe a good deal to the structure of traditional folk- and fairy tales in which similar patterns tend to repeat themselves. [Also to myth.] Butts refers to the ideas of both [Vladamir] Propp and [Joseph] Campbell as possible instruments to examine the structure of adventure stories, and to those of [Bruno] Bettelheim* to show the appeal of these stories. He also discusses Treasure Island in terms of folktale.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear

*Bettelheim was an asshole who set psychology back a couple of decades. Look up his theories on the causes of autism. (tl;dr: Refrigerator Mothers)

- The Epic Of Gilgamesh (the oldest known adventure story — 3rd millennium BC)

- Tom Sawyer (‘master text’ for adventure story as the Narnia Chronicles are for fantasy), but is itself an off-shoot of The Odyssey

- The legend of Saint George and the dragon

- The Greek tale of Perseus

- Robinson Crusoe (compared to Odyssean stories, the Robinsonnade keeps the characters in one place in order to focus on character development.)

- King Solomon’s Mines (1885)

- Jack and the Beanstalk

- Treasure Island

- Kim, Rudyard Kipling (1901)

- Peter Pan

- Sherlock Holmes

- The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings

- Doctor Who

- Star Wars (a parody of the hero adventure story)

- James Bond

- Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

- Cinderella, and any story using the ‘Cinderella Structure’ in which the hero can never go home again

For more on children’s adventure stories and their evolution, see The Centrality of the Adventure Story.

THE GOING-NOWHERE-FAST PLOT

In Children’s Stories

- Diary Of A Wimpy Kid books, especially those written before Jeff Kinney actively started writing the books around the fact they’d later be adapted for Hollywood.

- A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck, sequel to A Long Way From Chicago. Kirkus has this to say about it: “Peck’s slice-of-life novel doesn’t have much in the way of a sustained plot; it could almost be a series of short stories strung together, but the narrative never flags, and the book, populated with distinctive, soulful characters who run the gamut from crazy to conventional, holds the reader’s interest throughout.”

EPISODIC PLOTS

An episodic storyline is often a problem—except where it works beautifully.

@DonMaass at @WriterUnboxed explains how it’s done

@Roz_Morris

Here’s Howard Suber — another film guy — on episodic plot structures. He compares ‘episodic’ plots with ‘dramatic’ plots, and has a strong preference for the latter. The shape difference is simply that in dramatic structure the series of little mountains leads to one big one, followed by a steep drop off. You’ll have seen this shape all over the Internet if you’re interested in this kind of thing. It’s known as ‘the dramatic arc’.

Writers who describe themselves as pantsers (writing without elaborate planning) often turn out episodic plots. Sometimes these are edited into more linear stories afterwards, sometimes some of the episodic story remains.

The big advantage to episodic structure: It’s easy for your reader to sink right back into the story after you’ve gone away and come back. At least, that should be the main advantage.

The big disadvantage to episodic structure: It’s really easy to put the book down.

You can hear more about episodic stories by listening to the Pub Crawl podcast, Pacing episode.

Episodic stories…can be represented by a straight line with bumps in it. Stories with a dramatic structure end in a climax; stories with an episodic structure often just end.

Howard Suber

Elizabeth Lyons describes the shape of an episodic story as a series of little hills. She gives examples of the types of stories which most often use episodic plot shapes in her book Manuscript Makeover, which I recommend.

Streaming services such as Netflix are leading to binge-watching which is in turn leading to ‘episodes’ with a strong throughline.

In an exclusive interview with CBR, Price revealed that the animated series [F Is For Family] was meant to be more episodic, with self-contained stories instead of multi-episode arcs each season. After picking up the series, Netflix requested the creators use longer running narratives.

CBR

Sagas and Epics, usually set in historic time periods

Although the epic novel was originally in verse (Beowulf in the eighth century), it has now come to mean a historical novel with a giant sweep of time and peoples. Each book follows the lives of several generations.

- Shogun by James Clavell

- Treasure Island

- Lord of the Rings

- War and Peace

- Dickens wrote famously episodic stories, but there’s no surprise there — his novels were literally presented to the public as separate episodes. However, Dickens was and is still quite readable because he obviously had an overarching plot in mind. The episodic nature of his stories were probably due to the publishing realities impressed upon him.

Family Sagas

In family sagas the protagonist introduced in Book 1 of the novel may die. In Book 2 her daughter takes over and we read the events and challenges of her life. In Book 3 the granddaughter’s life continues, bringing the story of all three generations to an end. Each part or book may cover that character’s lifespan, with the expected and unexpected travails of the era. When a family saga is well structured, each protagonist in each section, book or generation has one story goal. There is one unifying element that creates the dramatic arc and this replaces the lower suspense of episodic writing.

- Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides chronicles three generations of a Greek-American family. There are many unifying elements and at the core is the quest to answer “Who am I?” and “What am I?” by the protagonist.

- The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough

- American Pastoral by Phillip Roth

- Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

- See an extensive list here.

The Picaresque

Lyons explains that ‘the picaresque is an old form of episodic structure that draws its name from picaro, a roguish protagonist who seeks adventure for adventure’s sake, or for some romantic ideal.’

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

- Tortilla Flat

- Lonesome Dove

- The Road

- Mad Men (which had its roots in a screenplay about “an American picaresque character,” according to Matthew Weiner. “By picaresque I don’t mean like Candide… I mean a guy who is making his own future because he has no other options.”)

- See an extensive list here.

On Miguel de Cervantes’ “Don Quixote”: A Discussion with Timothy Hampton

Don Quixote was written by Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes. He wrote it in two parts. Part one was published in 1605, and part two ten years later, in 1615. The story is centered around a middle aged guy named Alonso Quijano who is obsessed with stories of brave medieval knights—so obsessed that he decides to create a new persona for himself and live in a fictitious world of his own creation as Don Quixote. Don Quixote goes on all sorts of misguided adventures; fighting a windmill, jousting with a flock of sheep, and usually losing these battles in humiliating fashion. Timothy Hampton is a professor of comparative literature and French at the University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of Fictions of Embassy: Literature and Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe See more information on our website, WritLarge.fm.

New Books Network

Notice that Westerns, Anti-Westerns and Neo-Westerns feature heavily in that list. That’s because the West is well-suited to journeys along roads. Some scholars say that the genre of road movies are the ‘new picaresque’.

Lyons points out that the difference between a picaresque story and a more typically heroic one is all about character change:

Although the protagonists in these [picaresque] novels may articulate a hope or vague intention rather than a pressing story goal, reaching that hope or intention is not the point. The journey itself is the point, and the discoveries about self and life made along the way. Almost always, the picaresque story is a literal journey; the cowboys in Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry set out to herd cattle to Montana; the boy and Papa in The Road by Cormac McCarthy travel south in post-apocalypse America seeking warmth. But the picaresque is also usually a journey into expanded understanding. The cowboys learn that the journey is life and that life is for living in the moment. The boy and Papa are nurtured by their love for one another while moving through a land burnt and wasted from ultimate destruction.

Elizabeth Lyons, Manuscript Makeover

Interestingly, children’s literature expert Maria Nikolajeva categorises children’s literature in terms of ‘quest’ and ‘picaresque’ (rather than in terms of genre):

Quest has a goal; picaresque is a goal in itself. The protagonist of a picaresque work is by definition not affected by his journey; the quest (or Bildungsroman) is supposed to initiate a change. There is, indeed, sometimes a very subtle boundary between ‘there-and-back‘ and a definite, linear journey ‘there’, which is best seen in the last volume of the Narnia Chronicles.

Episodic Plots In Children’s Literature

- The Magic Pudding

- Anne of Green Gables. In their book The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer explain how Anne of Green Gables moves forward. They call this an ‘episodic plot’, as distinguished from a ‘climactic plot’.

Case Study: Anne Of Green Gables

It’s possible that episodic plots such as that of Anne of Green Gables allow us to experience a different rhythm of basic human pleasure. Each chapter is a dramatic plot of its own:

Although Montgomery’s story does move Anne from her condition of homeless waif to her understanding that a home both gives her an identity and makes demands of her, many of the incidents related by the plot are not necessary to the story. A large part of the pleasure of Anne of Green Gables, in fact, comes in the way the plot exceeds the sequential logic of the story: or, to use the phrase from William Touponce… these incidents “exceed structural functions”. For example, like many of the other chapters of the novel, the chapter entitled “An Unfortunate Lily Maid” takes the shape of a complete climactic plot. In a series of actions organized to increase readers’ involvement, Anne and her friends plan to stage the scenario suggested by Tennyson’s pome “The Lady of Shalott,” succeed in scrounging the materials they need to do so, and leave Anne lying in her “barge” to float down the river. The crisis occurs when the boat springs a leak and Anne begins to sink, and there is a satisfying climax when Gilbert rescues Anne. But the pleasure of the incidents reported here has little to do with the story of the novel. Anne’s disdainful dismissal of Gilbert’s heroism is the only incident in the chapter that contributes to the moving forward of the story as a whole. And even this incident repeats and amplifies information readers already have, rather than adding new information. In other words, there doesn’t seem to be much reason for this chapter to follow the chapter in which Anne dyes her hair green rather than to precede it. Montgomery’s novel is a string of such small climactic plots that diffuse the pleasures of readers rather than concentrating them on a single line of action.

Maria Nikolajeva

Interestingly, back in 1980, Nodelman called Anne of Green Gables ‘a story without a plot’. Nikolajeva suggests that this is only because Nodelman was looking for a male, linear plot, and this is why he viewed the ‘lack of plot’ as a flaw.

- The Worst Witch series by Jill Murphy, in which Mildred Hubble, the hapless student of magic gets herself into a different, self-contained scrape over the course of each chapter. Again, the pleasure of these chapters derives from laughing at Mildred and her nemeses, rather than working towards a conclusion.

- The Chronicles of Narnia

One of the few novels to successfully employ an episodic structure is Voyage of the Dawn Treader, something that makes it worth reading despite other problems. Dawn Treader is a travel story, and each island the characters stop at represents a self-contained episode, with its own conflict and pay off. But at the same time, each episode builds toward the overarching plot of their quest to find the Seven Lords of Narnia.

Five Popular Tropes Writers Struggle With

Climactic plots tend to be marketed to boys, while episodic plots tend to be marketed to girls.

Case Study: Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

Tom Sawyer is an interesting exception. Tom Sawyer is an archetypal adventure story, arguably ‘for boys’. Yet as Maria Nikolajeva points out in From Mythic to Linear:

At first glance, Tom Sawyer is very different in its structure from a typical quest narrative: there is no discernible home-away-home pattern, and the plot is episodic rather than progressive, as in the Narnia Chronicles. On closer examination there are at least two plots intertwined in the narrative: one progressive (or linear) involving struggle between hero and villain (Tom-Injun Joe), as well as treasure seeking and a princess; the other, indeed, episodic, where it is possible within every episode to discern the circular home-away-home movement.

In this episodic plot, Tom’s adventures take him, in concentric circles, further and further away from home, and into more and more perilous escapades: from Aunt Polly’s closet to the dangers of the cave. If the first chapters depict harmless “pranks” — pinching jam, playing hookey, getting other boys to do his work, blundering in Sunday school — the murder in the graveyard is more serious, since it not only initiates the second, linear plot, but also introduces violent death into what has seemed a harmless idyll.

Maria Nikolajeva

Maria Nikolajeva is telling us that Tom Sawyer is a mixture of winding, linear and spiral plot shapes. Huckleberry Finn is the same, but with a river in the world of the story which influences the shape of the story itself.

Notice that Nikolajeva has used ‘circular’ to describe what others call a classic, linear mythic plot (and which is known among children’s literature commentators in particular as a home-away-home story).

Below, Mavis Reimer also uses the word ‘circular’ when talking about any mythic journey which brings the child back home (rather than finding a new one):

Children on the move is the situation at the heart of most children’s literature.1 As Perry Nodelman and I argue in The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, the most common story for young people is a circular journey, in which a central child character leaves home in search of an adventure or is pushed out of an originary home by the behavior of powerful adults, journeys to an unfamiliar place, and, after a series of exciting and/or dangerous experiences, returns home or chooses to claim the unfamiliar space as a new home.

Mobile characters, mobile texts: homelessness and intertextuality in contemporary texts for young people

Mavis Reimer

But Reimer goes on to say that more recent children’s literature is less home-away-home and more what others have called linear and mythic, because there is no safe home at the end of the narrative:

The new millennium, however, has seen an increasing number of narratives for young readers internationally that challenge the terms of the earlier pattern. Since the 1990s, narratives about child subjects on the move have proliferated around the world: these children might be immigrants, refugees, or exiles, if the narrative is working within political valences; vagrants, street kids, runaways, or “throwaways,” if the narrative is working within (or against) the genre of domestic realism that continues to dominate the field of young people’s texts; or tourists and travelers, if the narrative is working within the terms of fantasy and adventure (including comic misadventure). What distinguishes these recent narratives from the generic pattern is that the central child characters do not move inside or settle at the conclusion of their narratives. Rather, they find happy endings – or, at least, narrative closure – in remaining homeless at the end of their stories.

Mobile characters, mobile texts: homelessness and intertextuality in contemporary texts for young people

Mavis Reimer

These stories tend to be episodic in nature. If you’re writing a modern episodic story, watch out for the challenges it presents.

- There is no obvious singular goal or single problem in a truly episodic plot, but you might choose to put one in.

- Modern readers are used to the dramatic shape and it’s hard to hold their interest unless the drama steadily rises.

- It almost never works in a genre story. However, there are exceptions. Harlequin has been known to ask for episodic romance.

- Make sure you haven’t accidentally written a thinly disguised autobiography. Life is episodic but successful stories are usually not.

LINEAR CIRCULAR PLOT

Circular muscles shut the eyelids. Linear muscles open the eyelids.

@DoctorKarl

There are cultures around the world who view time quite differently. For instance, Chinese cultures consider time and events as circular. There’s no need to worry about too much about what’s happening now because this too shall pass and things will come good again.

The basic pattern in children’s literature is the circular journey. That is, the plot follows the trajectory home — departure from home — adventure — return home. This pattern, which has its origin in European Romantic philosophy, can be traced to practically any children’s text, not necessarily belonging to what is commonly labeled as adventure genre. It can be found on different levels and in different shapes anywhere from picture books to psychological novels. The purpose of the journey is the maturing of the child (protagonist as well as reader), but the return home is a matter of security; whatever hardships and trials, the safe home is the final goal.

from Children’s Literature Comes Of Age by Maria Nikolajeva

Nikolajeva also writes of ‘the idea of the linear movement changing into a circular one’, which is very common in children’s stories, because children’s stories are often idyllic.

In all idylls, time is cyclical: either there is no linear progress whatsoever, or the linear development rounds back into the circular pattern […] Characteristically, in “realistic” books such as Little Women or Little House In The Big Woods, where the progress of chronos is inevitable, the duration of profane time is exactly a year. By the end of the book, the cycle is complete: “The attic and the cellar were full of good things once more, and Laura and Mary had started to make patchwork quilts. Everything was beginning to be snug and cozy again.”

In these stories, the seasons tend to be important. Winter is the season of low activity. Characters don’t get older. (The Moomin books, The Wind In The Willows etc.) The cyclical time is associated with the notion of home and the inevitable return home.

Nikolajeva distinguishes between ‘iterative’ time and ‘singulative’ time. In an iterative sentence, it is assumed that whatever is happening has always happened and will continue to keep happening. A singulative sentence applies to an action in this particular story.

Iterative: ‘In the winter time the Rat slept a great deal, retiring early and rising late. During his short day he sometimes scribbled poetry…there was a good deal of storytelling.’ (In which storytelling is a ritual act). There are a lot of iterative sentences in Anne of Green Gables, as well as in The Secret Garden.

The Narnia Chronicles are classic circular narratives — the children return to their original world after their great adventures.

A Diary Of A Wimpy Kid book looks very similar but more like the image below. This is because Jeff Kinney writes his gags first then fits a plot around it. Each gag has its own self-contained story arc, with the full seven stages of story structure. The stakes of each self contained gag are raised over the course of the story. So for example an early gag might be about Greg failing to get any sleep, but later in the book the whole family will be involved in a fake getaway saga, because Greg has imagined some fellow travellers are following them with the aim of stealing all their stuff. (That example is from The Long Haul.)

In Wrecking Ball, the episodes of Greg’s life come from the ‘present’ as well as the past, and culminate in a chaotic scene in which the Heffleys’ house is surrounded by all the unwanted opposition mentioned previously in the story. So although the diary entries seem episodic, they build to something big — a huge, unlikely, slapstick scene.

What about The Lion King? The theme emphasises circularity, but Simba goes on a mythic journey to ‘find himself’:

The Circle of Life presents the cosmic drama as a circular story. For all Simba and Arjuna know, lions ate antelopes and warriors fought big struggles for countless aeons and will continue to do so for ever and ever. The eternal repetition gives power to the story, implying that this is the natural course of things, and that if Arjuna shuns combat or if Simba refuses to become king, they will be rebelling against the very laws of nature.

Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

THE WHIRLPOOL PLOT

Stories about races, tournaments are likely to be whirlpool plots. The whirlpool metaphor can be applied to story shapes, too. Think of the opposing currents as opposing forces, each with their own desires and goals.

A whirlpool is a body of rotating water produced by opposing currents or a current running into an obstacle.

Wikipedia

Jane Alison in her book Meander, Spiral, Explode offers the example of Mr. Potter by Jamaica Kincaid:

I wonder if first person retrospective narratives — especially obsessive ones — might naturally follow a vortex. It’s how I’ve found lyric memoir to work; maybe it’s true of fictive versions of retrospection, too. A preoccupied (haunted?) narrator turns around and around in her hands the most potent moments of her past, gazing at repeating patterns and shapes as she spins. I see this happening — almost literally see a narrator turning a magic spindle in her hands — in Kincaid’s Mr. Potter.

Jane Alison

Jane Alison also encourages me to think about the following:

- If you’re reading a book and a lot of the sentences/chapters open with ‘and’, you might be reading a vortex plot.

- If you’re reading a book in which the narrator slowly reveals themselves to be an intradiegetic part of the story, you might be reading a vortex plot.

- If you’re reading a book with a witch storyline, and there are spindles and weaving and threads, you might be reading a vortex plot, because the spiral is a symbol indicating the voyage into one’s inner self, and a lot of witch stories are about that. Witch stories also tend to be feminine, and historically, only men were allowed to venture outside the house. (Which explains why a household item of servitude, the broom, became a magical flying device.)

See also: “Miles City, Montana” and “Tell Me Yes Or No” by Alice Munro.

In Children’s Fiction

A children’s literature equivalent of the spiral story is the picture book in which the reader returns to the same scene over and over, but the scene is a little different each time. For example, the picture and words will have built upon the previous page. The picture book version is perhaps an ‘upside-down vortex’.

- And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street by Dr Seuss is a classic example of this kind of book. The layout of each illustration is exactly the same but has more added to it each time.

- Oliver Jeffers’ Stuck is a story which returns time and again to the tree, each time with more unlikely objects stuck in it. The reason I think of it as an ‘upside-down vortex’ is because instead of funnelling objects out of the story, objects are added until the plot can hold no more. On the other hand, it is just a regular vortex if you consider not the objects themselves but the ‘options’. The options are gradually getting weeded out as we see they don’t work.

- 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher is a young adult novel in the vortex shape. Clay Jensen comes home one day to find a package waiting for him. Inside are seven cassette tapes. On the cassette tapes are the thirteen reasons why Hannah Baker has killed herself. As Clay listens to the tapes, he learns a lot more than he bargained for about the people around him, and comes to understand just how important it can be to reach out a hand to someone in need.

- Pretty Little Liars has a vortex shape which is not as successful as the mystery introduced in its adult-equivalent, Desperate Housewives, because it refuses to answer the main mystery at the end of the season, which ends up frustrating viewers. (Who killed their friend and the surrounding circumstances.) If a series tries to milk a mystery for too long the viewer/reader gets stuck inside the vortex.

THE FRACTAL PLOT

This pattern repeats over and over in nature. John Yorke is a big fan of this pattern to describe almost everything about how story is told, from the macro to the micro level. (See his book Into The Woods.)

Jane Alison calls this the fractals shape. In fiction, she posits many major writers (Woolf, Joyce, James, Bolano) create fractals at a sentence level. People have done word counts of their texts and found self-replicating ratios between sentence lengths.

Fractals are naturally hierarchical.

But the most fractal kind of work — ironically, since it seems like no order at all (to me) — is the stream of consciousness narrative.

texts that start with a ‘seed’ or blueprint that spawns several more

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode

Alison points out the distinction between fractal narratives and cellular ones: in cellular narratives the segments are equal. But in fractal narratives an initial segment is more likely to be compacted like a seed and generate the rest.

As literary examples of the fractal narrative, Alison offers “The Fifth Story” by Clarice Lispector and Crossing the River by Caryl Phillips.

FURTHER NON-LINEAR TERMINOLOGY

The non-linear story community has been deep into this particular plot shape for decades. When I say non-linear, I sometimes mean the Choose Your Own Adventure type of story, though the owners of that brand are very keen that we don’t use that phrase generically, so let’s call these stories Pick a Path.

Another word used by this community: ‘Dynamic fiction is a term suggested by Caelyn Sandel some months ago to describe her work.’ More on this term at Emily Short’s interactive storytelling blog. This word was suggested to replace ‘interactive fiction’, to get around the politics of that. Others have pointed out that there was already a word in use to describe dynamic, and that was ‘kinetic’.

interactive fiction — shortened to IF, which is a nice double meaning, since interactive stories are all about what happens ‘if’ the player does this versus that. Opinions vary widely about how ‘interactive’ a story must be before it deserves the term ‘interactive’ fiction. Is a page-turn-equivalent interactive? If that’s the case, a book made out of tree is interactive.

THE SIMULTANEOUS PLOT

‘Simultaneous plot’ is Howard Suber’s word for this plot. He credits its origins to one P.T. Barnum, who called his circus ‘The Greatest Show On Earth’. This guy:

At first staged his performances like everyone else — putting up a big tent with a ring in the centre into which he brought a succession of elephant acts, sword swallower, trapeze artists, clowns, monkeys, and anything else that might entertain people. But in 1870 he came up with an idea that has since been emulated in every other entertainment media: simultaneous, rather than sequential, action.

Being an expert in film, Suber points out that film is particularly well-suited to the simultaneous plot. It was D.W. Griffith who first demonstrated ‘cross-cutting’.

Suber breaks simultaneous action into two types:

- That in which the audience imagines time ‘freezes’ while we get to see what’s happening in a different place

- That in which the audience imagines ducking from place to place, seeing one bit but missing out on another.

Split focus is another technique film makers used when telling simultaneous/ex stories. That’s when the audience can see two things going on at once in the same scene, with one character positioned near the camera and another thing of significance positioned in the background. It looks a little retro today.

You might also call it branching or rhizome or connectedness.

What does rhizome mean?

Rhizome: A continuously growing horizontal underground stem which puts out lateral shoots and adventitious roots at intervals.

What does adventitious mean, then?

Adventitious: Happening or carried on according to chance rather than design or inherent nature.

For more on that, refer to Deleuze. Gilles Deleuze was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art.

The word ‘rhizome’ is also useful in a discussion of exploding or branching stories. Rhizome is a botanical word and means ‘a continuously growing horizontal underground stem which puts out lateral shoots and adventitious roots at intervals’.

Romantic heroes, whose relationship with the outer space is more intensive in comparison to Victorian characters, look for something they cannot ever reach, not even knowing where to look for it. Their perception of both space and time becomes fragmented and is later followed by the deterioration of their consciousness and existential anguish. The speed and at the same time inability to move produce an intensity which “constitutes the body as something absolute” and moreover, their ability to escape the infinite sorrow is gradually becoming vain when their journey approaches the deadly end or when it leads to infinite rambling.

The Romantic journey, according to Deleuze and Guattari, seems to be of the rhizomatic character: it has neither beginning nor end; it is made of lines only and has no structure which would consist of a set of points. As a product of the unconscious it displays a certain discontinuity and multiplicity accompanied by ruptures evoking chaos.

Concepts of Space in Victorian Novels

The branching/exploding form is especially suited to Postmodern stories, which tends to be highly experimental in form. Using this plot shape the artist can convey the idea that life is not just the progression of ordered sequences from some already given set of possibilities. Anthony Browne is the stand-out picturebook example of a Postmodern creator. See Voices In The Park for an example of interesting plot shape.

The Canterbury Tales is an example of an ancient exploding story.

When it comes to novels, I really like Jane Alison’s tips on how to pick an exploding — or radial — plot shape:

Narratives that strike me as radial are those in which a powerful centre holds the fictional world — characters’ obsessions, incidents in time —tightly in its gravitational force. That centre could be a crime or trauma or something a figure wants to avoid but can’t help falling into: something devastatingly magnetic. Unlike in a spiral, the story itself — the incidents we see dramatized — barely moves forward in time. Instead, a reader might have a sense of being drawn again and again to a hot core — or, conversely, of trying to pull away from that core. You might already know the end at the start and get many fractured views of the same moment, or many fractured views of things avoiding that moment. You might feel a sense of violent scatteration from a central point. Radials can be centrifugal or centripetal, but linear they are not.

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode

Centrifugal Force: Mud flying off a tire. TFW sitting on a merry-go-round and being pushed outwards while spinning.

Centripetal Force: the rotation of satellites around a planet. A satellite orbiting the planet is an example of centripetal force. Twirling a lasso, spinning a ball on a string. The force of tension on the rope pulls the object in toward the centre.

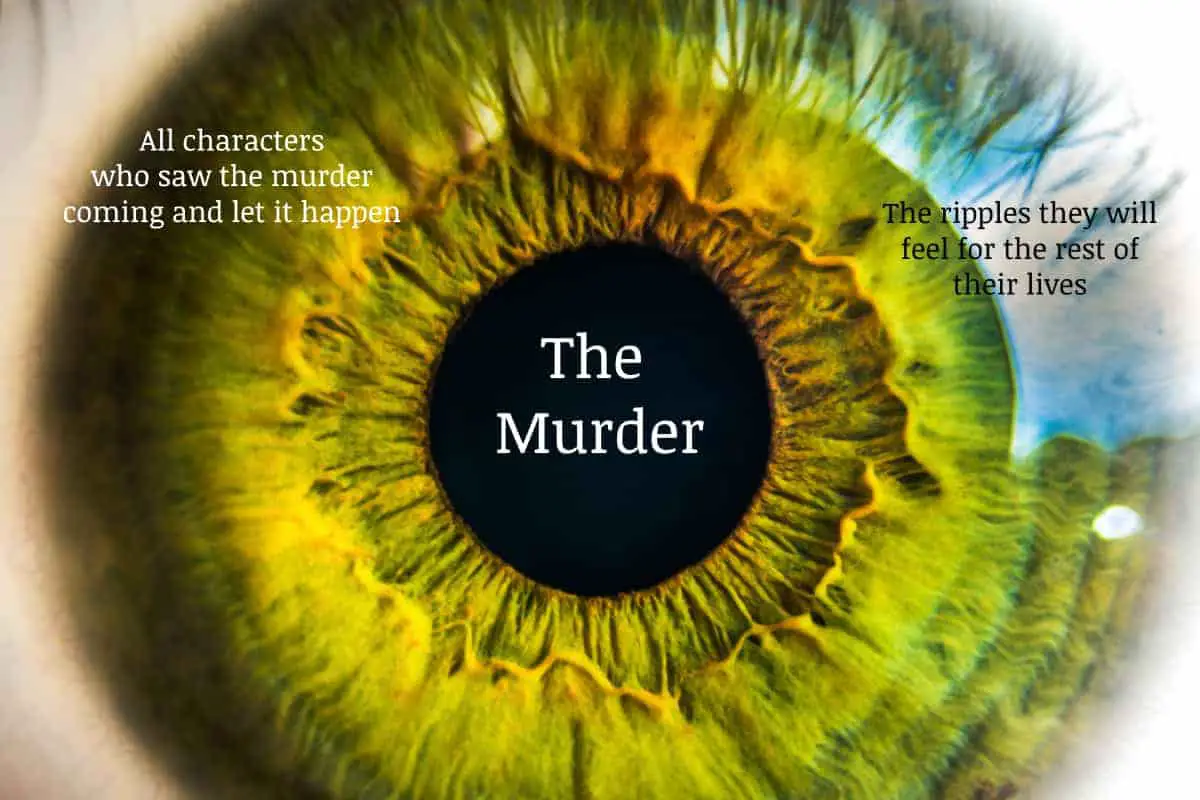

Jane Alison offers the example of Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel Garcia Marquez as an example of a radial or exploding plot shape.

Jane Alison describes Chronicle of a Death Foretold as an inverse panopticon. Instead of a guard keeping watch over prisoners (the original purpose of a panopticon), visible from his central vantage point, the murder happens in the centre of a circle of onlookers. (Modern, open plan living spaces remind me of a panopticon, which could be used to great horror effect in a suburban setting, imo. I like our older house, with its separate rooms with doors, which can be heated properly.)

Jane Alison also offers Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison as an example of a radial or spiral plot shape.

An excellent description of this plot shape can be found in the (Aotearoa New Zealand) Landfall review of Attraction by Ruby Porter:

[Ruby] Porter uses a fragmented style of storytelling [in her novel Attraction]: conventional chapters are divided into shorter sections and separated by a small plus sign, and some of the sections are very short – a paragraph, a couple of sentences even. Repeated throughout is the mantra, ‘Every time you remember something you’re only remembering the last time you thought of it.’ Rather than fracturing the flow of the novel, this gives the sense of accrual, each fragment an addition to what we know about the characters, dipping in and out of past and present, of memory and the dawning realisation of a dark family history which the narrator almost can’t bear to acknowledge. As the narrator confronts the fact that her ancestor fought against Te Kooti in the New Zealand wars, and that the money he was awarded for his service was used to buy the beloved family bach in Whāngārā, so too is the reader asked to examine their own place in Aotearoa’s colonial history.

The Biggest Raupatu, Landfall Online Review: Aotearoa New Zealand books in review

You might be reading a radial story if:

- A murder happens at the beginning and the narrative winds out slowly, showing how and why this happened, as in a ‘whydunnit’ rather than a ‘whodunnit‘. Whydunnits are considered more literary, generally. The whodunnit is a bit more genre, and the fun derives from second-guessing which of the cast it might be. (The best of these are also very cleverly written, make no mistake.)

- Lots of circle imagery combined with linear imagery, perhaps

- Perhaps themes around fate, which encourage the reader to ask: At what point could this tragedy have been averted? (What was the ‘crossroads moment’?)

- Characters who are blind to what’s really going on around them

- An extradiegetic narrator looking back on a time long ago with a significant amount of extra hindsight

- A series of vignettes with a kaleidoscopic, manic feel

- The reader pieces the story together bit by bit

Exploding Plots From Adult STORY

- Men, Women and Children, a film based on the novel by Chad Kultgen. The setting is important in this story because the characters are all beginning to integrate technology with their sexuality. As the story progresses the writer reveals how each character is connected.

- Enduring Love by Ian MacEwan — the past and the future spiraling around one inciting incident which happens in the first chapter, itself a micro study of a kaleidoscopic plot.

Exploding plots From Children’s Fiction

- After the First Death by Robert Cormier (1979) is a young adult novel which follows three different characters all involved in a terrorist attack. The narrative switches between characters as the action unfolds. The story begins with a narration from Ben Marchand, a teenager who was drawn into the hostage situation as a third party, and for whom the experience has changed everything, most notably the relationship with his father. As Ben tells his story from a hospital bed, the novel shows how the hijacking happened from the point of view of Miro – the youngest member of the terrorist group, a sixteen year old teenager.

I think Vonnegut’s a great writer. I mean, he’s a great writer who even when he’s bad he’s still more interesting and compelling than a lot of the books celebrated as the classics and the great books. But I think Vonnegut was also someone who had ‘an experience’. In his case, the Dresden Fire Bombing. [Big life changing events] do lead you to become unstuck in time. I think they do remind you that something that happens that is strong and powerful can never be isolated in the past. It happened then, and it will happen in the future. And it is happening now. This, for me, was the idea of time I grew up with. In Australia, in my era, we were brought up to believe in this idea of linear time. Well, we still are. The idea of history as we’re taught it is a linear idea, a European idea, a train that stops at all stations of human development.

But the idea of time I heard as a child — and all we had was stories — was circular. And the past was always present, the future always possible, and we lived in both. This idea is very strong in indigenous culture … I was sent an extraordinary essay by a young Youngu woman. They’re an Aboriginal people who live in North East Arnhem Land. They’re quite a remarkable culture.

In Youngu, they have as well as our three tenses of past, present and future, a fourth tense in which something that happened in the past is happening now and will be happening in the future. This woman, Sienna Stubbs, gives a beautiful example of going to make fish traps on the beach. And when you’re making them simultaneously with the people who were making them a thousand years ago. And people a thousand years hence are making them. This struck me as both utterly astonishing and entirely familiar. I think one of the myths we have in Australia … we still think of ourselves as culturally a European culture. But we’re not. We are the issue of the invaders and the invaded. As much as there was a process of colonization, there was a process of indigenization. Whether people wish it or not, we are not European in our outlook. We think differently. We feel differently. And so much of this comes from a 65 thousand year old culture that wasn’t extinguished on day one of the invasion, or ever.

Richard Flanagan: chain reactions, Friday 24 November 2023, Saturday Morning with Kim Hill, RNZ

THE REPEATING STORY

Some plots are more common in children’s literature. The repeating story is one.

In The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer point out that many children’s stories tell basically the same story twice…

…first in a straightforward manner and then with added subtleties. In Treasure Island, there is a short, exciting, but unsettling encounter between Jim Hawkins and the old pirate who stays at his inn, before Jim has the longer, more exciting, and more unsettling encounter with Long John Silver that makes up the bulk of the novel. The first of these encounters, less complicated version of the story that follows, foreshadows each of its major events. Similarly, Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows begins with the story of how Mole, unable to resist the temptations of the spring air, leaves his home and the duties of spring cleaning to find a more glamorous life of leisure on the river bank. After that, the book tells story after story of animals tempted to leave home. Those who go suffer for it and those who stay are praised. Mole’s story, then, exists as a kind of counterpoint to what happens in the rest of the book, as a one-sided version of the story of leaving home that acts as a schema for the more complex dilemmas of Rat and Toad.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

For a cartoon example of this structure see Courage The Cowardly Dog: “Hot Head”, Season One, 1999.

Roberta Seelinger Trites also writes of the repeating story structure and how common it is in feminist children’s literature in particular. Trites doesn’t use ‘repeating’ as terminology, but focuses on one type of plot that does fold back on itself — the story within a story. Granted, this is a slightly different thing, to do with diegetic levels, if you’re interested.

A common pattern among feminist children’s novels is the use of the “nested narrative,” that is, of a plot structure in which a framing tale contains some sort of story-within-the-story. The embedded narrative usually parallels the framing tale in both plot and theme. Gayle Greene comments on the prominence of embedded narratives as a mode of feminine communication when she describes their recurrence within postmodern feminist writing. Greene defines the reason for the proliferation of the structure within recent women’s novels as being a way for women to work through problems by revisiting them at different points in time in a pattern “which allows repetition with revision”. Greene notes that feminist critics and novelists alike have rejected the “linear sequence of traditional quests and Bildungsroman plots” in favour of more circular narratives. […] Thus, feminist children’s novels with embedded narrative structures are potentially a source of social criticism.

Moreover, as is the case with many parallel embedded narratives written for adults, such texts written for children tend to emphasise discussions of art and of creativity because the story-within-a-story creates an atmosphere wherein the very nature of narrative becomes a fundamental issue. Embedded narratives therefore complicate sequential narrative linearity by demonstrating that “life, as well as novels, is constructed through frames, and that it is finally impossible to know where one frame ends and another beings.”

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Waking Sleeping Beauty

This kind of ’embedded narrative’ is a cousin of the parallactic story — a form of narrative in which any given temporal event is shown to the audience through the viewpoints of various characters. This means there’s no ‘eye of god’ and no concept of ‘the real truth’. Stories like these convey the idea that there is no such thing as the truth.

A graphic of this plot might look like a circle within a circle, or a baby inside a mother. There would be an umbilical cord linking mother and child together, but these stories are about human connection in general — human connection starts with the mother. Trites calls this the ‘maternal narrative structure‘:

In and of itself, the narrative structure of the embedded narrative evokes for the reader a textual representation of a mother’s pregnant body. With its housing of one narrative body within another narrative, the structure implies feminine fertility, so nested narratives can themselves become a child-of-the-mother image; the subnarratives are the offspring of the narrative. The very structure of a nested narrative places a metaphorical value on birth.

Moreover, the maternal embedded narrative evokes the awareness of interpersonal connections that Gilligan associates with feminine decision making. The story-within-the story establishes a weblike structure from within which a storyteller communicates about the importance of community. The structural pattern of the nested narrative represents the interconnectedness of narratives, while the thematic content of the story emphasises the interconnectedness of relationships, especially between mother and daughter figures. Nested narratives that follow this pattern reproduce mothering in that they articulate the maternal process as a creative, artistic process. When this articulation occurs, the text joins form and function to glorify the maternal body. And this pattern may encourage child readers to question such social traditions as delegitimising motherhood and such prescribed narrative traditions in children’s literature as the linear plot.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Waking Sleeping Beauty

In short, the maternal story structure is a political stand against the linear plot shape, which is dominant.

Another useful term here may be ‘chiasmus’. This describes parallelism at the sentence level, but we might also apply it to plot shapes.

CHIASMUS (from Greek, “cross” or “x”):A literary scheme in which the author introduces words or concepts in a particular order, then later repeats those terms or similar ones in reversed or backwards order. It involves taking parallelism and deliberately turning it inside out, creating a “crisscross” pattern. For example, consider the chiasmus that follows: “By day the frolic, and the dance by night.” If we draw the words as a chart, the words form an “x” (hence the word’s Greek etymology, from chi meaning “x”) … The sequence is typically a b b a ora b c c b a. “I lead the life I love; I love the life I lead.” “NakedI rose from the earth; to the graveI fallclothed.” Biblical examples in the Greek can be found in Philippians 1:15-17 and Colossians 3:11, though the artistry is often lost in English translation. Chiasmus often overlaps with antimetabole.

Literary Terms and Definitions

In children’s literature, The Enormous Crocodile by Roald Dahl and The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson have a chiasmic structure. In both cases, main characters enter the woods/forest, meet a succession of opponents (so far, so mythic), but then the story plays out again, backwards this time.

‘Aperture’ Endings In Children’s Literature

The ending in a repeating plot is oftentimes an ‘aperture’ ending.

Many people associate children’s stories with happy endings, but in contemporary works, there is not always a happy ending. Instead, we may see an APERTURE.

An aperture is a new opening, indicating further possibility for character development.

An aperture plot allows for many possible endings.

Readers might expect a sequel from such an ending, but this sort of ending would in fact be ruined by a sequel since readers are robbed of the chance to envision an ending for themselves.

Aperture has become very common in modern children’s literature. Some even say that it is now banal.

To counteract the banality, some modern stories now return to a happy ending, but with an ironic undertone.

The Rhetoric of Character In Children’s Literature by Maria Nikolajeva

ALTERNATING STORIES

Some children’s novels also present alternating stories that operate as variations of each other. Martha Brooks’s Bone Dance alternates between the stories of two teenagers, both concerned in different ways with understanding their aboriginal heritage, family history, and connection to and claims to ownership of the same piece of land. In Welwyn Wilton Katz’s Out of the Dark, similarly, alternating stories describe how a young boy in the present and a somewhat older man in the ancient past work out their relationships with the original residents of a new land they have come to —the same place in different times. And in His Dark Materials, Lyra and Will must deal, alternately and then together, with parents who have abandoned them, dangerous enemies who want to destroy them, and magical instruments that give them power.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Where the characters of these separate stories come together near the end, this is sometimes called a zipper story.

Zipper story. A particular form of story involving two (or more) alternating strands, which in the story’s beginning appear completely unrelated but which over time come closer and closer together until their connection becomes the story’s climax. Fred Pohl’s novel Gateway is a zipper story. (CSFW: David Smith)

Glossary of Terms Useful In Critiquing Science Fiction

- If I Stay by Gayle Forman is an interesting case because the plot alternates between before the car accident and back to the present. The next in the series, Where She Went, is from the point of view of Adam, Mia’s boyfriend.

- Will Grayson, Will Grayson, which was actually written by two separate writers

A downside to this is the tendency for readers to enjoy one point of view more than the others, which means the switch feels a little irritating. Perhaps this reward the reader as much as it ‘punishes’ and isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It is worth writers examining the reason for writing in an alternating point of view. I’ve heard it advised that in a story about a girl, it’s a good idea to ‘draw boy readers in’ by including the male perspective. I’ve also heard it said that in boy-girl shifting narratives, the boy chapter should open, otherwise boys will be alienated by the voice of a girl. I can’t even be bothered digging into what’s wrong with that view, but be aware that it’s out there.

The Affair is a TV series for adults which does an interesting thing with its alternating (and repeating) plot structure. (It is also a classic parallactic story. See above.) First we see a family man about to embark upon an extramarital affair. Then the perspective shifts to the target of his affection and the audience is encouraged to reflect on his story — the woman’s point of view depicts him as far more predatory than the story from his perspective. This series expects the audience to bring quite a lot to the table — hopefully the audience has already read between the lines and suspects the man from the outset, as he mansplains stuff to the black female principal of his children’s school. I found this series so uncomfortable that I couldn’t bear to watch more than half of the first season, but I admit it’s a very interesting and useful structure for a story, asking us to examine the nature of truth and subjectivity, as well as who we tend to believe. This could be modified for the young adult literature market to examine some very uncomfortable injustices, and in fact has been utilised by Malorie Blackman in Noughts and Crosses. This is probably a trend which started in young adult literature and moved up into the world of adult fiction, as so often happens.

The alternating story is perhaps showcased best in linked short story collections.

LINKED NOVELLAS

a.k.a. novels-in-stories

Related to this is the linked novella. Instead of each dash, imagine any kind of story shape at all, each intersecting with each other. Each story can be related

- thematically

- by setting

- by mood

- by situation

- by character

Adult Examples

- The Joy Luck Club

- various Alice Munro collections e.g. The Beggar Maid

- This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz (a milkshake duck)

- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

- Kate Forsyth wrote Winter Greens (a Rapunzel story) in a form which emulates the main imagery: that of the braid. She writes with three strands of story, braided together. Sometimes the structure of a story is inspired by the imagery.

Examples From Children’s Literature

- Homesick by Roshi Fernando

RELATED

- The Shapes Of Stories by Kurt Vonnegut

- When it comes to non-linear stories — in the sense of pick-a-path type stuff, the shape of your plot becomes critical. See a dedicated non-linear storytelling blog for more on that.

- Some literary people talk about ‘modular’ versus linear short stories.

- Shapes to be wary of by Nick Mamatas, including the wine glass and the three hills (though I think his ‘spiral’ shape actually refers to a point of view problem, not a plot shape problem).

- Writing Narrative Endings — a teacher’s reflections on teaching students how to end a story, one of the most difficult things you can teach. It relies on an understanding of plot shapes.

- Picture book writers often break picture book plot shapes down according to this taxonomy, or similar.

- Tips for Non-Linear Narratives from Nathan Bransford

Header painting: Ernst Haeckel, (German, 1834-Jena, August 8, 1919), Illustration No. 71, Stephoidea from Art forms in Nature, 1904