“Miss Smith” is an early short story by Irish-English writer William Trevor. Find it in The Day We Got Drunk On Cake And Other Stories (1968) and also in Collected Stories.

Like “Mrs Silly”, a later William Trevor story, “Miss Smith” is the story of a woman as told (partly) via the point of view of a middle-childhood-aged boy. I would recommend this story for study in the high school classroom, for students who can cope with, say, Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery“.

“MISS SMITH” DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- When and where do you think this story was set? Any clues?

- How do you feel towards James at the start of the story?

- What do we learn from small details about James’s background?

- How do you feel towards Miss Smith? Have you ever had a humiliating classroom experience like that, or seen it happen to someone else? How did other students react?

- Did you find it surprising that James would leave flowers for Miss Smith even though she treated him with disdain?

- What is the contemporary meaning of ‘gaslighting’? How is it used (and misused)? Where does the word come from?

- Why might Miss Smith’s new husband have doubted the mental stability of his wife? (Hint: Look up the etymology of ‘hysteria’. What is postpartum depression?)

- William Trevor creates an example of gaslighting for his titular character (the former Miss Smith) but he also gaslights the audience, in a way. How does he achieve that?

- Describe Trevor’s choice of narration. Whose head are we let into, and how does point of view shift? Why has he narrated the story in this way?

- At what point do you become anxious for the toddler?

- In very general terms, what do you think has happened to the child? How has William Trevor led you to that conclusion?

SETTING OF “MISS SMITH”

PERIOD

“Miss Smith” was published in the 1960s but I can’t reliably place it within a decade. If you have detailed knowledge or memory of school heating practices, this would help. (The classroom is heated with one of those old-timey stoves you see in Anne With An E.)

DURATION

About four years

LOCATION

William Trevor was born in Ireland in 1928. and moved to England at the age of 26 (the mid 1950s), so he’d have kept his Irish accent for a while, even when writing English characters, I’d assume.

Is this set in Ireland? I’m going by the dialogue, and even then, only by the rhythm. At any rate, this story is set somewhere in the UK, and could be set in one of many small towns where everyone knows everyone.

ARENA

The school is the centre of Miss Smith’s life. The small town is surrounded by swathes of nature.

MANMADE SPACES

A small town, more like a village.

NATURAL SETTINGS

The meadow of flowers at the end is an ironic setting. Generally we associate meadows with utopia, rest and calm. Horror writers love to subvert these associations. The abundance of sunlight and colourful flowers in the film Midsommar work to similar effect.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

In the 1940s, women had far fewer rights. Miss Smith had few options available to her. She would have been a ‘clever girl’, so her options were to become a teacher or a nurse. Girls in the trade stream would become secretaries and factory workers, but only until marriage. No matter her cleverness, women were expected to work (at lower pay than men) for a few years, then get married and have babies. The war disrupted that somewhat, but once men returned from WW2, women who had briefly experienced economic independence by contributing to the war effort outside the home were railroaded back into the home.

I suspect this brief taste of freedom only made things more difficult for women. Women suddenly saw for themselves that they were perfectly capable of working outside the home, and saw firsthand (or secondhand via their mothers) how the patriarchy was actively banding together to keep women excluded for no reason other than to hold onto power.

This came to a head near the end of the 1960s in America, later in rural parts of the English speaking world, and this is when William Trevor was writing the story.

Still, women had no access to birth control (let alone abortion healthcare), were unable to have their own line of credit, take out a mortgage, or remain welcome in the workplace after marriage. The gender pay gap has never gone away, but back then it was codified, because women, as people, were worth less than men, as people.

Depression following childbirth is a very common hormonal issue — so common it’s actually more normal than not. Modern research tells us nearly 70-80% of women experience some depressive symptoms within the first two weeks following delivery. In some women, depressive symptoms persevere and can include psychosis.

Women have long tried to hide signs of depression, sometimes with dire consequences when their depressive symptoms turn into thoughts of harming themselves or their babies. A well-publicized example is that of Melanie Stokes, who killed herself in Chicago in 2001 after suffering postpartum mental illness.

Sadness and Support: A Short History of Postpartum Depression, 2013)

That paper offers a snapshot of perinatal depression through the ages:

- Middle Ages: any stigmatised individual (mostly women) was thought to be a witch or a victim of witchcraft.

- 1500s: the first descriptions in literature of “a disturbance of the maternal instinct”. Crimes of women who killed their babies were called “melancholic filicide”.

- mid 1800s: The first physicians made detailed case reports of mental disturbances around childbirth, noting it was higher in new mothers than in the general population. Treatment plan: careful nursing, tepid baths, purgatives (strong laxatives). In America, one physician advocated a prescription of opium. (Prescribed for all sorts of things at the time.)

- Later that century women were advised to bleed (to reduce inflammation and eliminate excess fluid). Women were also kept away from their own babies. (See “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gillman, the stand-out short story about perinatal depression. Perkins Gillman was herself diagnosed with hysteria, which comes from the Greek word for uterus. Only people with uterus received a diagnosis. In Ancient Greece, men thought the womb wandered around the body, causing all manner of conditions. Obviously, the idea took hold, persisting across many centuries.)

Perinatal depression continues to carry stigma, but nothing like it did back then, when people didn’t how the words. Women may have spoken about “the baby blues” among themselves, but it was considered a moral issue, not a hormonal, biological one. Even for mothers who never experienced psychosis, or even depression, the fact that women commonly did experience this (and still do) led to the widely-held notion that women, as a class of people, are unstable, not to be trusted and are not always the best person to take care of their own child. This was of course compounded for women of colour. Here in Australia, Aboriginal women were having their children forcibly removed, leading to intergenerational trauma of The Stolen Generation.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

When you belong to a class of people who is regularly mistrusted, talked over and not believed, this has a compounding effect. By the time Miss Smith’s husband accuses her of mental instability, she has been primed by the culture to put aside her own conviction.

The very best people to witness this in action: Adults who have gone through gender transition, read by others as both men and as women. Paula Stone Williams speaks to this point in a TED talk. Paula lived the first 60 years of her life (misread) as a man.

Apparently since becoming a female I have become stupid. I guess it’s the loss of testosterone and the arrival of estrogen that has caused me to lose the brain cells necessary to be a fully functioning adult human. Either that, or I’m as smart as I ever was, it’s just now I’m being constantly subjected to mansplaining. […] This happens all the time now: I have to go three or four rounds with someone before I get a direct answer. And there’s a deeper issue. The more you’re treated like you don’t know what you’re talking about, the more you begin to question whether or not you do, in fact, know what you’re talking about. Right? I understand a woman’s tendency to doubt herself.

Paula Stone Williams, 2012

NARRATION OF “MISS SMITH”

William Trevor had a good understanding of how Miss Smith came to lose confidence and personhood within marriage. He conveys this milieu without ever really getting into her mind.

What do I mean by that?

Let’s go through the sections of the story, using the following terminology:

- Psycho narration: Narration is so deep inside a character’s head there’s no need for dialogue tags such as “he said”, “she imagined”. Whatever’s on the page is coming straight out of the character’s head. Other, similar terms: Stream-of-consciousness, interior monologue.

- Light penetration: Meaning ‘light penetration into the mind’. Narration gives us more than what TV could give us, but not much more. Now and then you get a “he said” or a “she imagined” or something reminds the character of a memory from the past, etc.

- Cinematic: If this story were made into a short film, nothing would be lost because nothing happens in the story that couldn’t be shown on a screen. We have no description of what characters are thinking. Cinematic is different from ‘omniscient’ because an omniscient narrator can jump from one character’s head to the next. Modern readers aren’t used to omniscience and don’t tend to accept it (though they won’t necessarily know why). In any case, publishers aren’t interested in publishing it, which creates what’s available in the first place.

One popular choice, especially for late 20th century writers: Jumping back and forth between cinematic and light penetration. It’s far more difficult to bridge the gap between psycho narration and cinematic. But readers won’t notice the shift between 2 and 3, unless you stuff it up. Avoid stuffing it up by 1. doing it on purpose and 2. recognising when it might be a problem, in which case hit a double carriage return. (And make sure your editor doesn’t accidentally edit the double carriage return out by including a hashtag!)

William Trevor opens with cinematic narration. He switches to light penetration with ‘James thought:’ This makes James the empathetic character. We are supposed to put ourselves in his shoes. Also, readers are like ducklings and fall in love with the first character we truly understand. On top of that, we like characters whose thoughts we can see. That’s because understanding leads to empathy. This holds true even when we morally disagree with their choices. So long as we can see why they made them.

After the double carriage return, William Trevor does something with point-of-view which you don’t see often now:

When Miss Smith married she stopped teaching, and James imagined he had escaped her for ever. But the town they lived in was a small one and they often met in the street or in a shop. And Miss Smith, who at first found marriage rather boring, visited the school quite regularly.

Whose head are we in? Both. James ‘imagined’ and Miss Smith ‘found marriage rather boring’. William Trevor is making use of omniscience. (In a writing group, someone would call it head-hopping.)

The complicating factor is this: As the story progresses, James gets older. He is also revealed to be stalking her. So it’s possible this is not omniscience at all. It could be knowledge that James gains and deduces by careful scrutiny of Miss Smith. But we don’t know that yet.

The section then slides into a description of Miss Smith’s home life that James couldn’t possibly know. We see her with her husband, having private conversations. ‘He complimented her sweetly.’

STORY STRUCTURE OF “MISS SMITH”

SHORTCOMING

Miss Smith humiliates one of her students. She doesn’t like him at all. Via her dialogue we see her trying her best to not let that show. But we are inside the thoughts of James, and we know her actions affect him plenty.

DESIRE

Once married, Miss Smith misses her teaching life. But she goes along with societal expectations and quickly becomes pregnant.

OPPONENT

In order (see ‘Extrapolation’ below):

- The new husband

- Her own conscience/James

- Her own baby

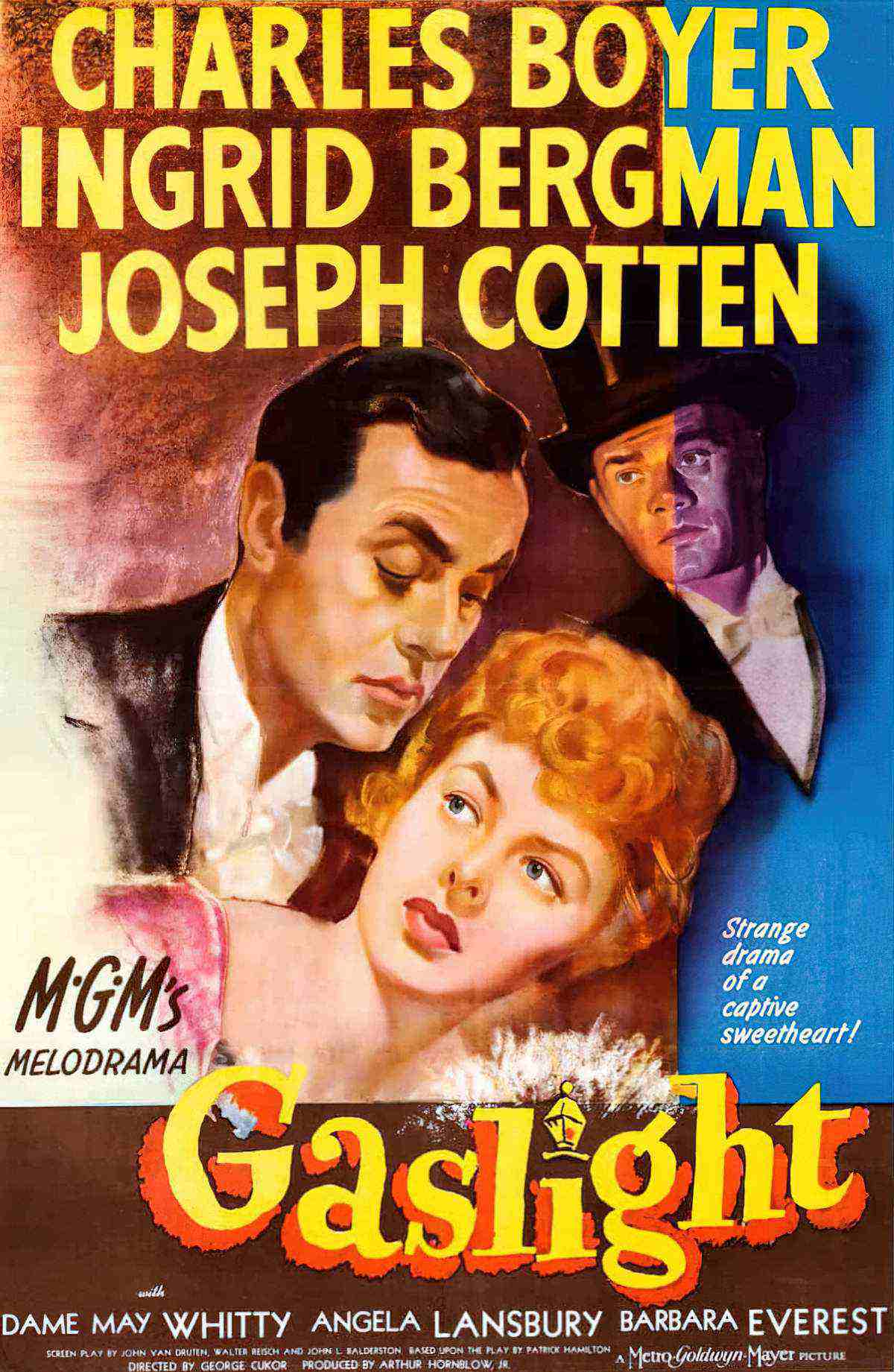

Let’s get intertextual for a moment and talk about Alfred Hitchcock’s 1944 film Gaslight, a psychological thriller based on a 1938 stage play. A husband turns down the gas-powered lights so they flicker throughout the house. When his wife asks why the lights are flickering, he denies they’re flickering at all, suggesting it’s all happening inside her head.

Few people were using the word ‘gaslighting’ fifteen years ago. Suddenly it hit mainstream usage, I believe as a result of feminist activism and discourse around domestic violence. Now the word has such a wide meaning it’s less useful than it was before.

MEANING OF GASLIGHTING: A technique of coercive control. One person intentionally works to ensure another person no longer trusts their own perception of reality.

GASLIGHTING IS NOT: Insistence, perseverance, or continued disagreement.

PLAN

Children don’t typically make firm plans, instead guided by their ‘compulsions’, as William Trevor puts it:

Almost without knowing it, James developed a compulsion about Miss Smith. At first it was quite a simple compulsion: just that James had to talk to God about Miss Smith every night before he went to sleep, and try to find out from God what it was about him that Miss Smith so despised.

“Miss Smith”

He decides to pick flowers for Miss Smith and lay them at her house. When children know an adult with power doesn’t like them, they tend to go one of two ways: They either muck up, or try to appease. James has taken the second route.

Of course, this doesn’t work because he has been stealing flowers from other people’s gardens, which makes Miss Smith look bad. Also, she finds him creepy. Notice how William Trevor conveys what happens next, picking up the pace with narrative summary:

After that, James thought of Miss Smith almost all the time. He thought of her face when she had caught him with the flowers, and how she had afterwards told his father and nearly everyone else in the town. He thought of how his father had had to say he was sorry to Miss Smith, and how his mother and father had quarrelled about the affair. He counted up all the things Miss Smith had ever said to him, and all the things she had ever done to him, like giving him seed-cake at the Christmas party.

Next, James has a chat to a trusted adult in his life, without revealing the entire scenario. With limited knowledge of the interior world of James, the man who comes to cut the grass inadvertently gives James deadly advice. Note that the trusted adult is not a parent or a pastor or a teacher — a man who seldom sees him. Yet if James comes from a family with enough money to pay a man to cut the grass, he comes from money.

We don’t see James after that. The point of view switches wholly to Miss Smith. Helpfully for storytellers, out of sight, out of mind, we sort of know James is behind the disappearance.

Andrea Arnold sets up a similar dynamic in her film Fish Tank. In both cases, a child who has been mistreated by an adult seeks revenge by taking what is most precious to them: Their own offspring.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Someone turns the gas on and almost kills the sleeping toddler. The husband blames the wife and insists on paying for home help even though it is beyond their budget.

Then the toddler goes missing. James turns up like a creepy horror child and says, “Would you like to see your baby?”

ANAGNORISIS

I noticed myself reading more quickly on the final page, as I raced to learn what had happened to the child. (Did you do the same?)

We learn for sure that James has been stalking his former teacher, and it was James who tried to kill the child by turning on the gas.

We might also revise our opinions of Miss Smith. As a teacher for James, she fell short. She humiliated the weird kid which would have contributed to his social ostracization. With no friends, he clung to Miss Smith instead, but Miss Smith didn’t like him. He continued to appease, offering her his fountain pen. But nothing he did was enough.

NEW SITUATION

I’m glad we never see via a scene what the mother finds, and what happens to James next.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Reading on a metaphorical level, is James even real? Or is James the ‘creepy child’ the former Miss Smith imagines her own baby might turn into, because postnatal depression has prevented her from forming a close parental bond?

I know, I know, this is an unusual take. But consider the narration, and the strange shifts in point of view. We are at times inside the head of Miss Smith and of James at once. This could be omniscient narration, or it might be close third person, actually. When James turns up out of nowhere in the room where Miss Smith is sitting, he appears as would a ghost. The scene in the meadow could be a daydream which turns into an anxiety dream, not because the baby has gone missing. This could be anxiety talking. Or, maybe Miss Smith did do something to her baby. If she is stuck in a coercively controlling marriage, the conversation she imagines between James and the grass-cutting guy could be Miss Smith thinking about how she can get back at her husband.

‘My little daughter’s smaller than you. If you hurt her, you see, you’d be hurting me. It’d be just the same, you see.’

‘I see,’ said James.

“Miss Smith”

Note that James wears glasses. Because James cannot see. Likewise, he cannot see into his teacher’s mind, into her home and marriage. When he turns up ghostlike, sunlight streams through the window, turning them into ‘mirrors’. (Note the symbolic importance of kitchens and their link to womanhood. What do James’s glasses mirror, exactly? Miss Smith herself!)

Miss Smith has seen James before, also ghostlike:

A small boy, so quiet she scarcely noticed him, stopped her once by a sawmill.

“Miss Smith”

To add further substance to this metaphorical reading: A mental shift happens when you have your own child. Now you know what it’s like to be a parent. You’re also taken back to your own childhood, forced to revisit even the parts you thought you’d forgotten.

If you were a teacher in your pre-parental life, you look back on all the kids you taught with fresh eyes. Miss Smith has recalled a boy called James and realised she treated him badly. Now she’s a parent herself, she has regrets. She should have treated that kid better.

Though he’s gone, the memory of the boy continues to haunt her, contributing to her lack of self-worth, initialised by postpartum depression. At the same time, it’s difficult for her to experience retroactive sympathy for James because he clung onto her, hanging around in the classroom while she was trying to do her marking. In the primary school classroom, there’s usually one or two kids who are clingy with their teachers like that. But there’s no one more clingy than your own baby, who needs a caregiver for its very survival. The baby would also remind her of the clinginess of that kid called James.

“Miss Smith” could thereby serve as narrative for the struggle new mothers so often feel between loving their babies more than anything, and also struggling to retain individuality. We never learn Miss Smith’s new married name, which is, of course, exactly why William Trevor never tells us, and why he includes the line, ‘But Miss Smith laughed and said that she was not Miss Smith any more.’

The child goes missing on his third birthday. This is a coincidence. How would James know it’s the child’s third birthday? The mother would definitely know.

Also, the link to the Hitchcock film encourages my reading of Trevor’s story as a psychological thriller.

RESONANCE

Stories in which women are misbelieved, mistrusted, ignored and deemed ‘crazy’ have not gone away (especially in psychological horror) because the gender hierarchy has not gone away.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The header illustration was made with the help of Midjourney AI art generator.