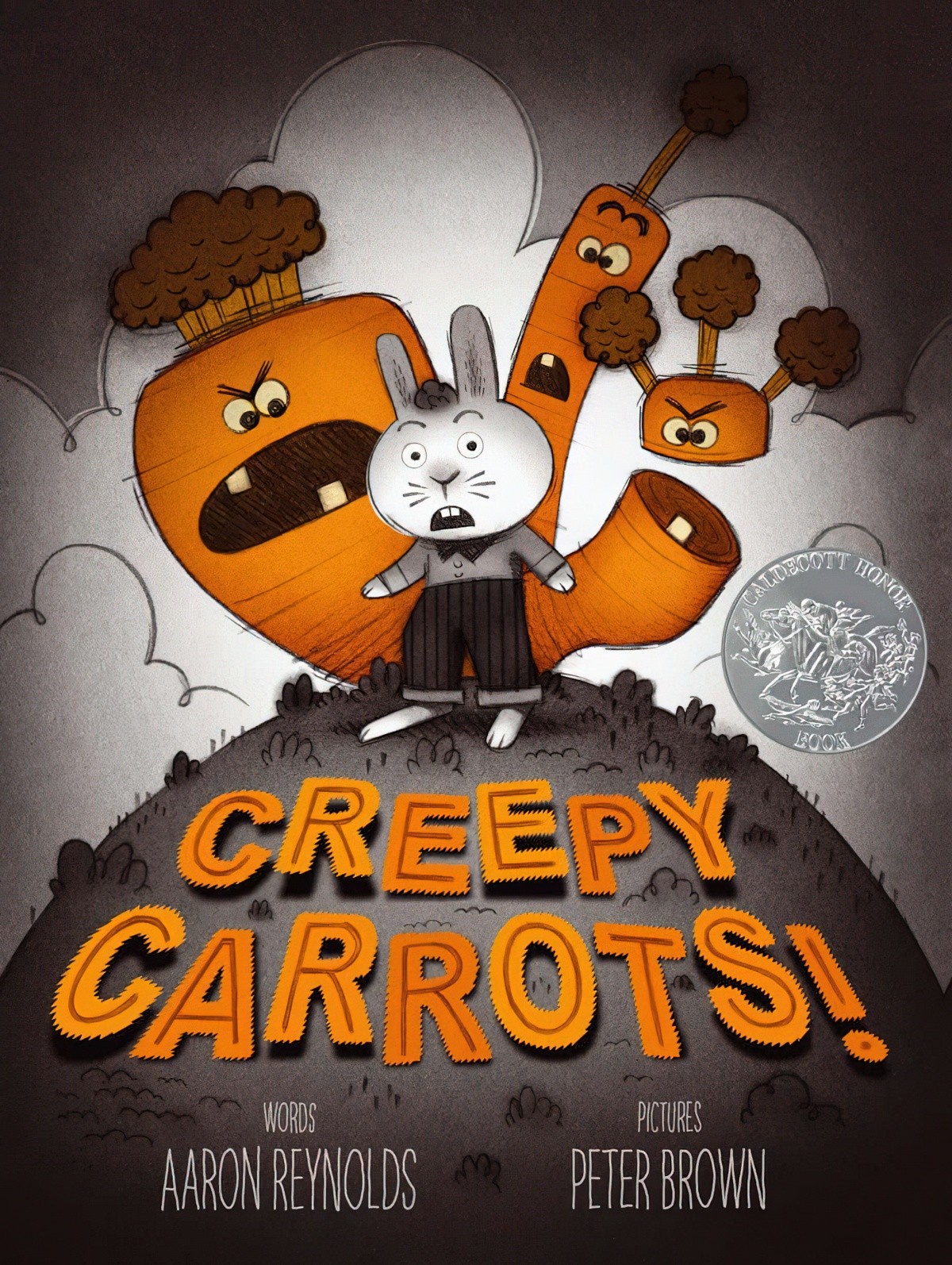

Creepy Carrots (2012) is a picture book written by Aaron Reynolds and illustrated by Peter Brown. For anyone wondering how to create a scary book for the very young reader without keeping them awake all night, this book is our masterclass in the horror-comedy blend.

First of all, the story is about carrots — a familiar, everyday food item not typically associated with horror. This story is therefore an inherently funny ironic juxtaposition.

Vegetables and horror make an especially great combo for humour, especially in a book for children.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS

COLOUR

For an American audience, and increasingly for a worldwide audience, black and orange signify Halloween (thanks to pumpkins).

(The same author/illustrator duo make use of green as their accent colour in Creepy Pair of Underwear.)

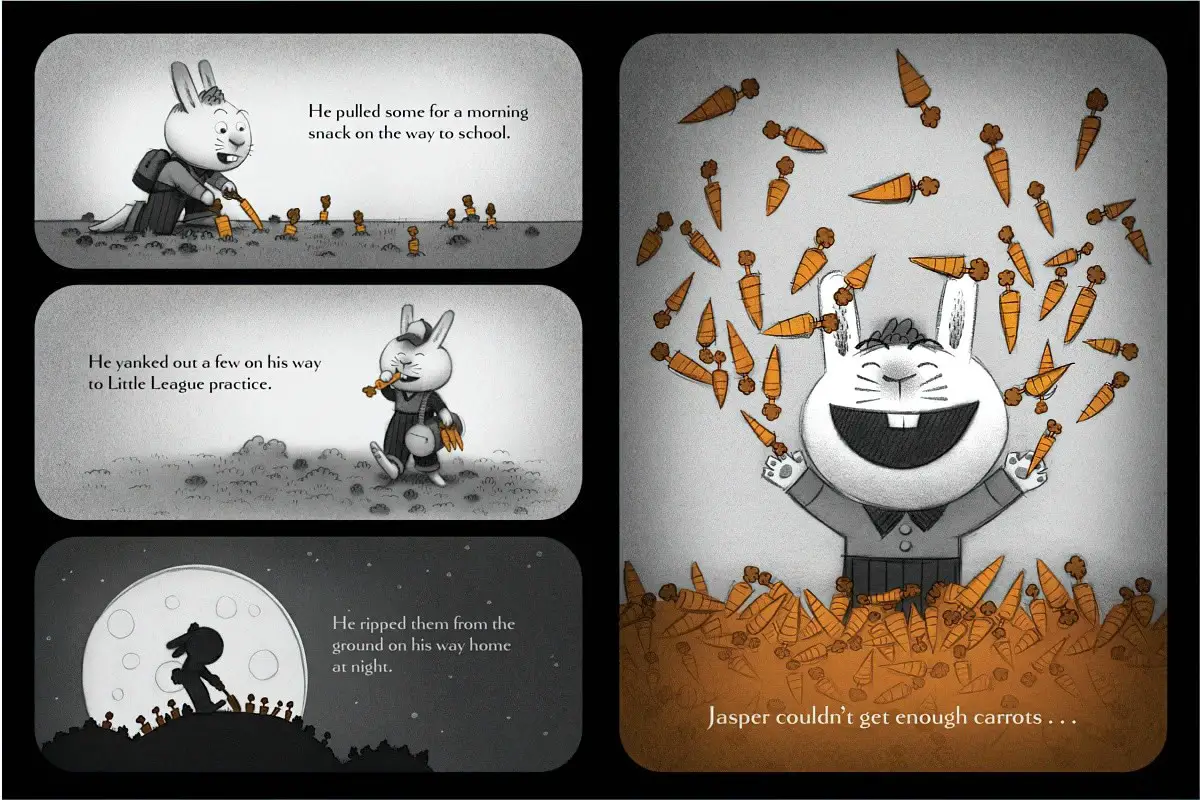

The orange accent colours of Creepy Carrots don’t just look cool. They help the young reader do much of the work of decoding: When Jasper thinks he sees carrots, he is ‘really’ seeing other orange things in his environment. (Or is he?) Accent colours tell the reader where to look.

NOIR

What is ‘noir’ anyway?

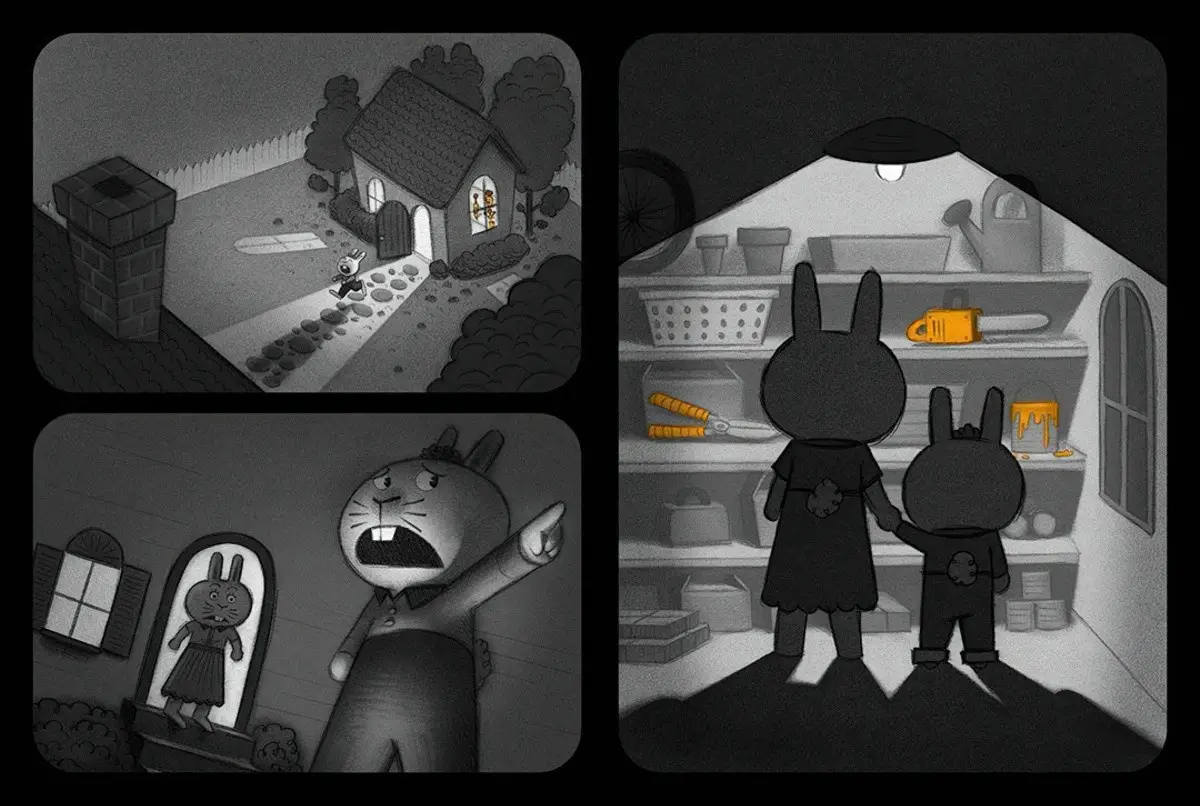

For a good overview, check out these free noir movies.

Some say it’s a word made up by the movie industry and has no real definition. But we still know noir when we see it, right? It’s dark, it’s chiaroscuro, the shadows are long, the angles are highs and lows, emphasising power imbalance (between empathetic main character and villain). In the illustration below, Brown uses both high and low angle on the left side. Jasper rabbit is tiny and powerless; next he is powerful. It’s not until we get to the second reading that we realise he IS huge and powerful in relation to certain vegetables at ground level. The ‘camera’ is switching from reader point of view to carrot point of view. Then we get an unmarked one-point perspective of mother and son gazing into the cupboard.

HOW ARE THESE ILLUSTRATIONS COMFORTING AS WELL AS SCARY?

Instead of angular, they are rounded. The character design of the rabbits are very ‘Miffy’, and Miffy (by Dick Bruna) is cosy. The roundness of the ears in Creepy Carrots is mirrored in other parts of the illustration: Rounded arches of the door, round light bulb, round edges of household objects and, significantly, rounded bushes in the carrot field.

HORROR TROPES IN THE ILLUSTRATION

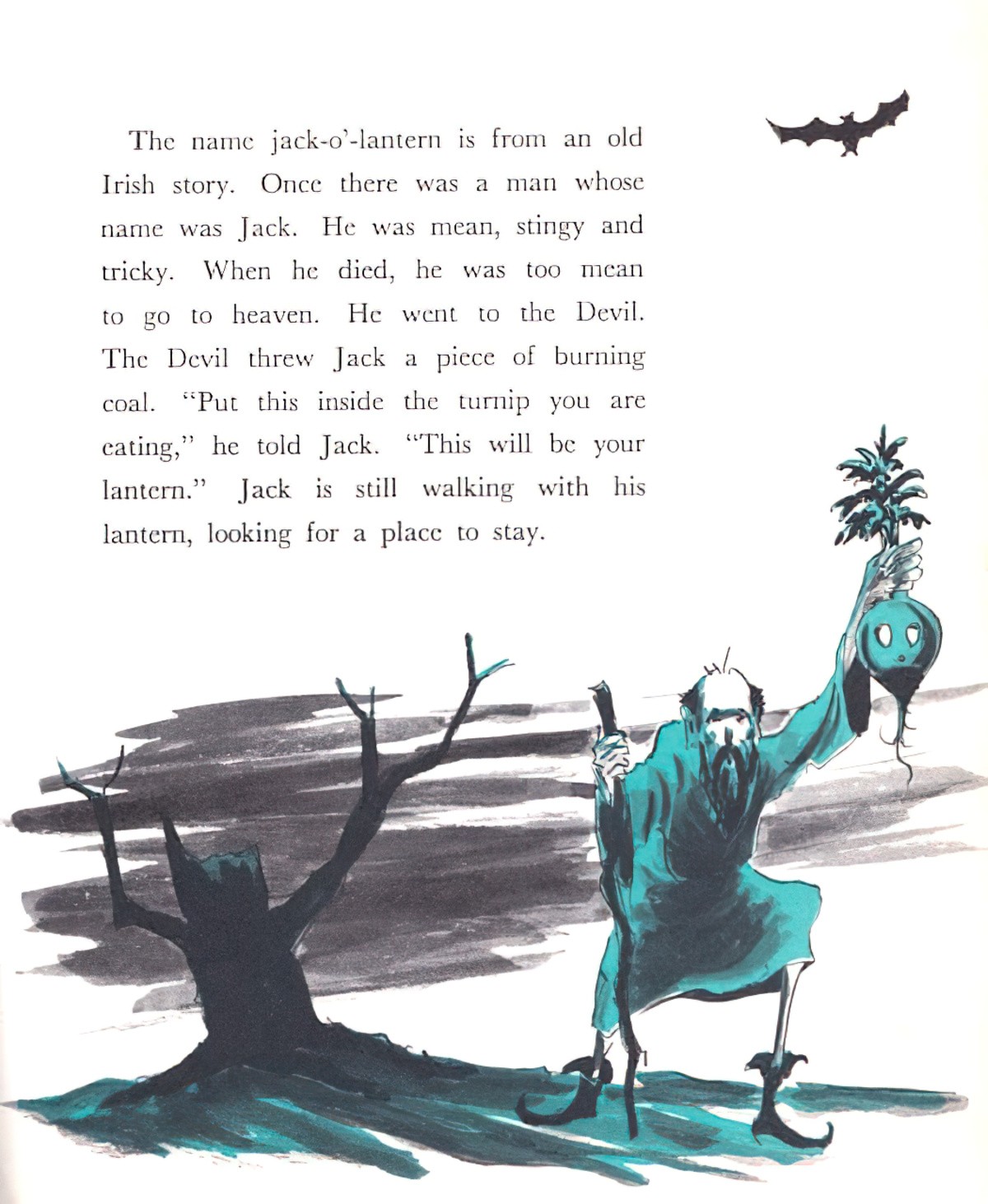

There’s a long-standing connection between Halloween and vegetables. Today we most likely think of the pumpkin.

But do you also think of turnips?

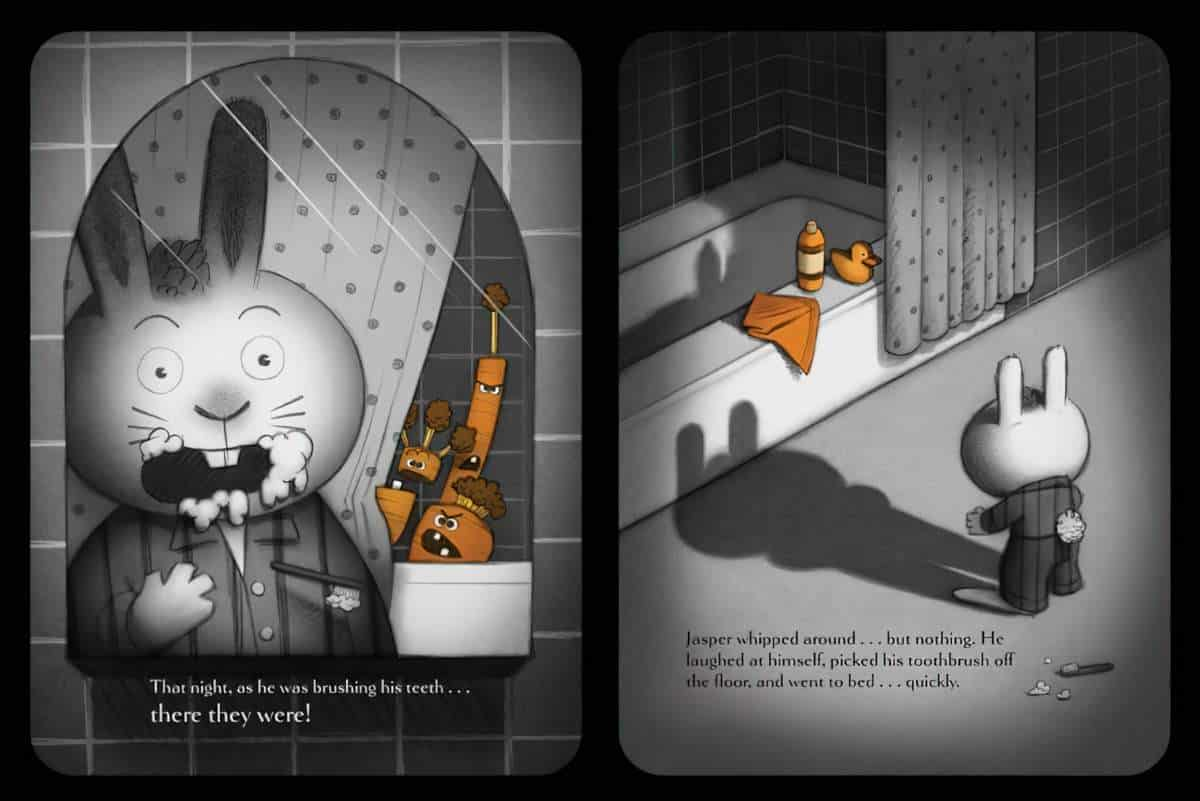

Apart from the noir tropes, which are clearly perfect for horror genres (and basically synonymous with it), in Creepy Carrots Brown has utilised the photography trope of horror.

In really old horror stories, mirrors/glass/looking glass was instrumental as a technology to help people see into the supernatural world. Once photography had been invented, horror storytellers naturally started to use the technology of photography for the same purpose. The borders of the ‘comic boxes’ in Creepy Carrots are rounded to match the rounded shapes of the objects within, but older dual audiences will definitely recognise the film strip quality. These illustrations look like the negatives of a film strip, if you’ve ever seen a film strip.

I just asked the resident 12-year-old if they knew what a film strip was. The answer to that was yes, but they couldn’t name it, didn’t see how it had been used as a motif in Creepy Carrots, and had no concept of taking a roll of film to the pharmacy/dry cleaners’/chain store to get it developed. They’ve never seen a film strip in real life, though it clearly remains a cultural symbol for now.

However! Once I watched the video by Peter Brown outlining his art inspo for Creepy Carrots, I realised those rounded corners were inspired by the rounded corners of old TV sets rather than film negatives. Just goes to show how different readers get different things out of art. The end result — interestingly — is identical — the feeling of being watched via a thin veneer (be it the photography lens or via the TV screen).

Betsy Bird got something a little different again:

Previous Brown books like The Curious Garden had fun with the borders, filling them with creeping smog around the edges. In Creepy Carrots! the borders now teem with encroaching darkness. Each picture is enclosed in a black border that seeps a foglike substance into the images. It’s like watching a television show or a movie where you know something’s gonna get the hero sometime. You just don’t know when.

Betsy Bird

SETTING OF CREEPY CARROTS

The shelves of your average children’s room abound with titles that are “scary” enough for a small fry. The trick is to find something that manages to balance the funny and the frightening in equal measures, never overplaying its hand.

Betsy Bird, children’s librarian, reviewer, podcaster

The story clearly takes place in America, but the ‘Americanness’ is probably only evident if children live outside America. There’s the Little League team, the bed which is raised off the ground providing a creepy nook below; the sleeping alone. These are not features of all cultures, not by a long stretch.

STORY STRUCTURE OF CREEPY CARROTS

If you watch/read a good number of horror stories you’ll recognise the plot:

- Main character sees something weird but doesn’t believe his own eyes.

- Main character sees the same thing but this time in the mirror.

- The world seems to go back to normality.

- The weird thing reappears but this time the main character cannot ignore it.

- Main character seeks help from an authority figure (in this case Jasper’s mother).

- The authority figure cannot see what the main character sees.

- Now another sense is engaged. The main character hears the weird thing as well as seeing it.

- Main character summons a different authority figure (in this case Jasper summons his father). Again, not believed.

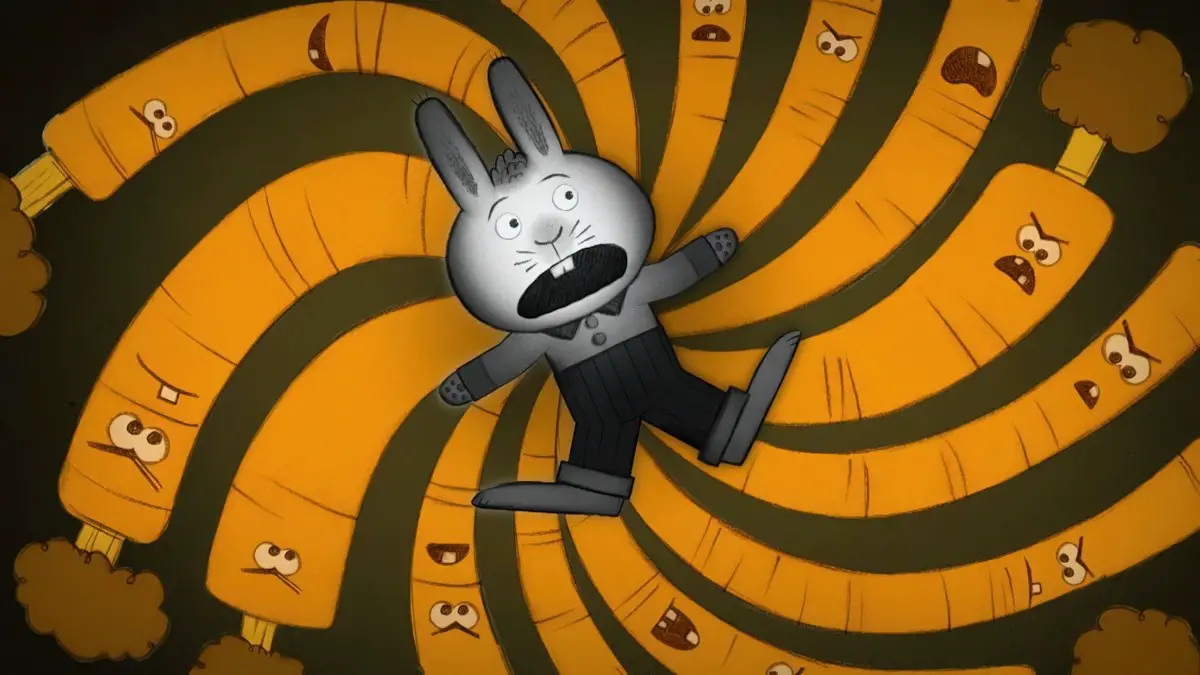

- Spiral into madness

- Realisation that main character is right to worry about the weird thing, which definitely exists in the world of the story.

- Main character makes a plan to live with the weird thing (or dies, in cosmic horror).

PARATEXT

The Twilight Zone comes to the carrot patch in this clever picture book parable about a rabbit who fears his favorite treats are out to get him. Jasper Rabbit loves carrots—especially Crackenhopper Field carrots.

He eats them on the way to school.

He eats them going to Little League.

He eats them walking home.

Until the day the carrots start following him…or are they?

Celebrated artist Peter Brown’s stylish illustrations pair perfectly with Aaron Reynold’s text in this hilarious eBook with audio that shows it’s all fun and games…until you get too greedy.

Marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

On the very first page, in a Peter Rabbit sort-of- plot, a boy rabbit helps himself to carrots in someone’s garden. When Jasper says the carrots are ‘free for the taking’ we know he is wrong about that. But we expect the gardener to come after Jasper (not the carrots themselves).

Though these carrots are not ghosts, this is basically a ghost story until the big reveal. In ghost stories, the ghost will stand in for a psychological shortcoming in the main character.

Deep down, Jasper must feel a bit guilty for taking these carrots. While telling himself they’re ‘free for the taking’, he knows they’re not, right?

DESIRE

Jasper wants to eat delicious, crunchy carrots. Sometimes you just have to ignore reality and run with an established trope: That rabbits eat carrots. However, I know from experience (of pet rabbits escaping and running rampant through the vegetable garden) that rabbits prefer the green tops of carrots and will happily leave the orange root that humans prefer.

OPPONENT

The carrot field is called Crackenhopper’s Field, and the voiceless velar plosive /k/ is clearly connected with horror because we see the same cosy horror name in Monster House, a feature-length film about three kids who solve the mystery of the haunted house across the road — owned by an old man called Nebbercracker.

But we never do see who ‘owns’ the field — it is eventually revealed that the field probably belongs to the carrots themselves.

Most stories have a double layer of opposition: family/friends/peers and then the big, bad opposition (let’s call it the Minotaur).

In this story we don’t see Jasper’s peers on the page, but significantly, we do get a sense of Jasper as part of a peer group. He’s the all-American boy; he goes to school, he goes to Little League practice, and we are told he has won a game against the East Valley Hares. He has plenty of natural kid-like opposition, and this is left off the page, because this habit of stealing carrots is part of his secret life.

The Minotaur opponent here is the field of carrots, who are following Jasper. However, this dangerous opponent is revealed to be benign, which is why this picture book is suitable for the youngest of readers.

PLAN

In a children’s story, as well as in most horrors, the main character first tries to engage helpers from the cast of characters around them. In thise case, Jasper summons his mum and then his dad, but neither is any help. This is one common way to ‘get rid’ of the parents: they don’t see what their children can see. The child is psychologically and actually alone.

The reader doesn’t know this until the end, but it’s not Jasper with the ‘plan’. Jasper is simply driven by his basic desire for delicious food. Meanwhile, the carrots have decided to follow Jasper home with the specific purpose of creeping him out.

Eventually Jasper comes up with a plan. As is typical for a picture book, the writer is not backwards in coming forward:

Jasper hatched a plan. First thing on Saturday he grabbed supplies and headed to Crackenhopper Field.

The reader must read the pictures to understand the plan.

- Jasper builds a fence around the carrots

- Jasper digs a moat

- Jasper fills the moat with water

- Jasper builds a massive fence around the moat

A truism of modern picture books (in particular): The characters go completely nutso with their plans. Just when the reader thinks they’ve done enough, the character goes one step further. Or, the storyteller goes one step further.

But first, the storyteller often tries to persuade the reader that the story is over. That’s what happens in Creepy Carrots:

His plan had worked.

(We know it hasn’t, because we know stories must contain an Anagnorisis/Reveal/Gag.)

Other examples of contemporary picture book hyperbole followed by the comic flip/gag/reveal:

- In Stuck by Oliver Jeffers, a boy throws many things into a tree hoping to dislodge his kite, until he throws a whale into the tree (which also gets stuck.)

- In I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen, a bear walks through a book asking various characters if they’ve seen his hat. He doesn’t realise the rabbit right in front of him is wearing it.

- In Wolf Comes To Town by Denis Manton, a wolf , ridiculously disguised as various townsfolk, steals (acccumulates) a variety of things.

- In Chatterbox by Margaret Wild and Deborah Niland an older brother tries hard to get his baby sister to talk.

- In A Squash and a Squeeze by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler (based on a much older folktale), an old woman feels her house is too small. A wise man counterintuitively advises her to fill it up with animal after animal.

Significantly, a story with this comedic cumulative structure does not end at the part where nothing bigger/more ridiculous can possible happen. There must be an unexpected gag after the accumulation of ridiculousness. This type of story can be considered carnivalesque.

The flips/gags/reveals:

- In Stuck, the firemen who come to the rescue also end up in the tree.

- In I Want My Hat Back, the rabbit possibly gets eaten by the bear.

- In Wolf Comes To Town, a boy goes missing. (The wolf has killed the boy.)

- In Chatterbox the baby sister busts out with fully-formed sentences and now she won’t be quiet.

- In A Squash and a Squeeze, the old woman’s house feels more spacious than before once she gets rid of the animals.

This story structure extends beyond picture books, of course. Here’s an example of comedian Tom Sainsbury making use of it. The story is completely different from Creepy Carrots, but the underlying structure is the same:

- The accumulation (the build-up)

- The flip/reveal, in which the opponent has their own plan

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This plot of Creepy Carrots follows a tried-and-tested horror progression which spirals the main character into madness. Notice how wonderful and also funny the ‘spiral’ is — the spiral of madness is made of bent (out of shape a.k.a angry) carrots.

ANAGNORISIS

The gag is the part where the audience learns what’s really going on, though I could just as easily call this part of the story ‘the gag’.

In Creepy Carrots we learn that the carrots have wanted a boundary around them all along, to save themselves from being eaten. Their sneaky plan has worked beautifully.

NEW SITUATION

The carrots are now safe inside their structure.

The book’s finale is one of those twist endings that some kids will get while others just enjoy the visuals. I love a picture book with a good twist, and so do child audiences. Particularly when they don’t see where the story is going.

Betsy Bird

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

We can assume Jasper doesn’t go back to the carrot field. We also know that the carrots are not really villains. They are empathetic characters who could just as easily be the viewpoint characters in this story. All is well with the world. All is fair and just. (I assume Jasper finds some different carrots to eat, since we must all eat something.)

RESONANCE

Creepy Carrots was a Caldecott Medal nominee in the year following publication, and is likely to become a classic.