**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

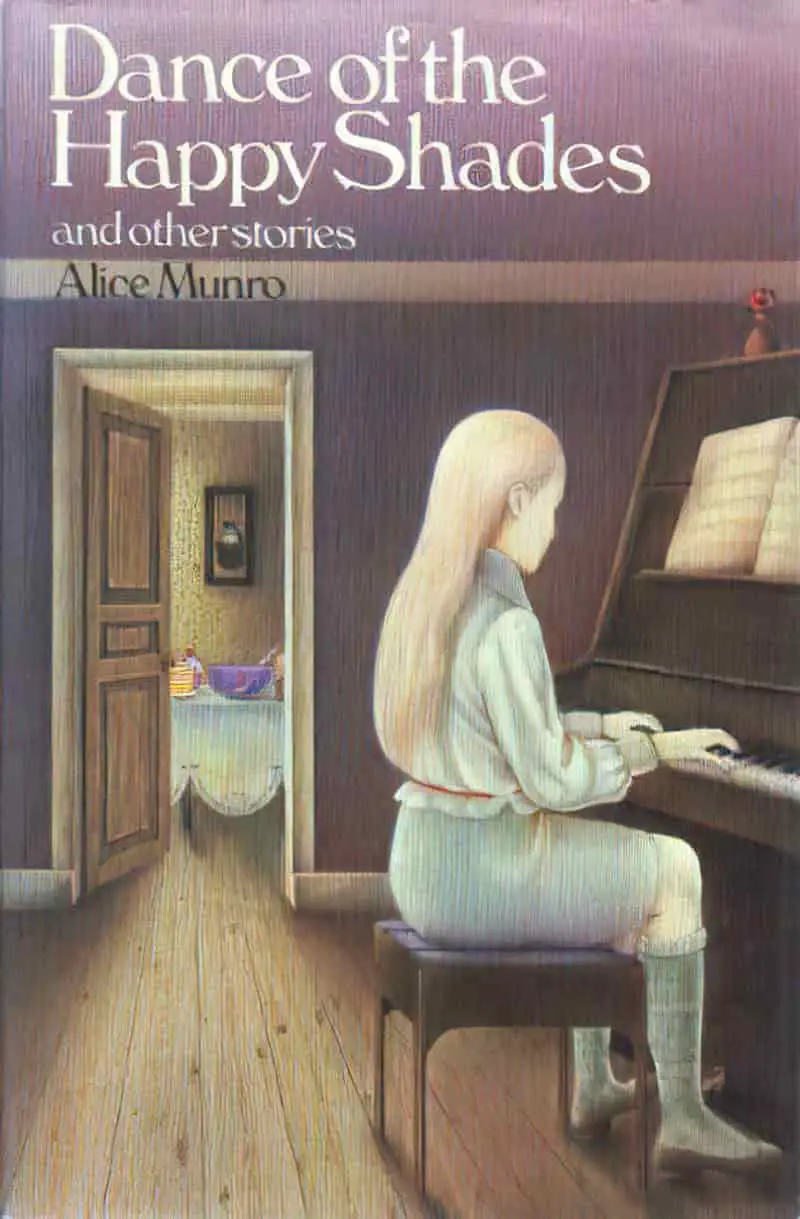

“A Trip To The Coast” is a short story by Alice Munro, first published in Dance of the Happy Shades (1968).

In stories, trips to the coast often coincide with a big self-revelation. A character looks out to sea, realises something, and the audience understands their life is about to change in some significant way.

The sad irony of this story: There is no trip to the coast. However, there is a self-revelation, or rather a gentle shift as a girl sits in that liminal space between childhood and adolescence. This story will end on a cliff-hanger. Why? This story will leave you as unmoored as May is feeling.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “A TRIP TO THE COAST”

The story opens in present tense with the image of a tiny town of three houses and a store, reminiscent of something out of a Wild West genre paperback. The town is even called Black Horse. Surrounded by fields of weeds, this place is nowhere near any coast. (I do a close reading of this opening paragraph here: Writing Activity: Describe Main Street Of A Small Town.)

A switch to the past tense. We’ve zoomed into the store of that small town called Black Horse, and the three people who live in the store.

MAY

The story opens with young May as viewpoint character.

- Eleven years old

- Has entered a modest stage of her life and is made fun of for this

- Generally prefers to sleep in rather than get out of her bed on the porch to fill people’s gas, but this morning she’s up early, enjoying the solitude. Until she realises her grandmother is up already. Her grandmother seems to get to everything before her, which is a disappointment.

GRANDMOTHER

The story zooms out to give a pan shot of all three members of the household, then zooms in on the grandmother.

- Seventy-eight years old

- Runs the supply store

- Hears everything but only answers if she feels like it

- Talks right past her granddaughter

- But then says things like, “I might as well talk to a barn wall” when her grand-daughter does try to take the old woman up on an offer of conversation

- Widowed

- Is getting to the point where she’s contemplating her own death

- Perhaps tricked her young granddaughter that she was dead once, when she was only sleeping on the sofa. Alternatively, she really was sleeping and May simply feels she was tricked.

- ‘Things dangled on her despite her attempts to be tidy and fastened up’

- ‘with her hair pulled tightly over her skull she had the look of an under-nourished but maliciously intelligent baby’

- Rolls her own cigarettes on a little machine

- Professes no religion

- Prides herself on her ability to take care of herself, economically, practically and emotionally

- Grandma is basically a burlesque witch, a comedy archetype

HAZEL

- Thirty-three years old

- May’s mother

- ‘a tall, drooping woman’

- ‘a long, wary face and an oblique resentful expression emphasized by a slight cast, a wilful straying of one eye’

- Works in a store in nearby (fictional town of) Kinkaid

- Curls her hair and irons her dresses, in stark contrast to her mother

- She must hold out hopes of marrying because she has a glory box full of nice household items. But instead of using these she lives with her mother in the middle of whoop-whoop and eats of her mother’s chipped plates instead of the nice ones in her glory box. (For any young readers: A glory box or hope chest was typically filled with items including towels, aprons, linens, and sheets to gift to young women when they married and left the family home.)

- On Saturday nights she goes out on the prowl, to dances and whatnot. She comes home hungover, which probably means she drinks and drives the 30 miles back to Black Horse.

- With the help of aspirin, she spends Sundays singing in the church choir.

- Like the father in “Images” does to his cousin and live-in nurse, Mary McQuade, the grandmother of this story likes to tease her daughter about possible potential husbands.

Once the readers have met these three women over coffee at their home/local supply store, the story jumps to a scene including today’s special visitors. Heather Sue Murray has been mentioned as important by young May, though the grandmother didn’t seem to care about the girl.

This is not Alice Munro’s usual storyline. Critics have counted at least twelve short stories in which Alice Munro writes about an older mother and a caregiving daughter. This story has even been called Munro’s ‘obsession’. But in “A Trip To The Coast” we have an inversion of that dynamic — an elderly mother who refuses to accept care from her own daughter and granddaughter. She would rather die. In fact, she’d prefer her daughter move out, let her die in peace.

HEATHER SUE MURRAY

- Eunie Parker’s cousin

- ‘has been a Highland dancer ever since she was three years old’

- (like Patricia in “The Time of Death“) Heather dances in competitions

- Calls Eunie and May ‘you kids’, suggesting she is just a tiny bit older

- Wears lipstick and shaves her legs

EUNIE PARKER

- A girl of the same age

- Who has been May’s best friend for two years

- Whoever Eunie is, she pales to insignificance next to stage dancer Heather Sue Murray.

- Is trying to impress Heather Sue, and is embarrassed when the more straight-forward May reveals that she and Eunie hang out at the graveyard quite often, because there is a patch of shade there and because they aren’t bothered by other local kids.

THE GIRLS DECIDE TO GO FOR A SWIM

Since Heather May is creeped out at the suggestion they might sit in the graveyard, Eunie suggests a swim at Third Bridge, half a mile down the road.

May asks her grandmother’s permission to go. Comedically, the grandmother asks where she’s going to be swimming. Funny because there’s only one place for swimming.

Grandmother says no. Because that’s where the boys go, and May is getting too old for that.

The reader may notice the irony here: The Grandmother is very keen for her thirty-three year old daughter to marry and move out. But her eleven-year-old is on the other side of that window, and is too young to be having anything to do with boys whatsoever. Considering this comes from a woman who otherwise seems not to care about social customs, this irony highlights the strong social pressure for women to partner up, and only within a very narrow window of life.

MAY IS LEFT ON HER OWN

This part is heartbreaking to anyone who has ever been a child. May has been looking forward to the visit from Heather Sue Murray, but her ‘best friend’ Eunie Parker ditches May in favour of the visitor.

The pair of them run off laughing and whooping it up as soon as they understand May won’t be allowed to join them at the river.

The grandmother reveals to May that she saw Heather getting off the bus, and did not like what she saw.

MAY RETREATS

With nothing else to do on her own, May sits by the pump and spots a toad. She catches it in her hands.

Grandmother approaches it. Annoyed at the grandmother, May starts taking out her frustration on the toad, poking it with a stick in the belly. (The inverse of a Save the Cat moment, and an example of everyday lateral violence.)

Grandmother tells her to stop that.

GRANDMOTHER SUGGESTS A TRIP TO THE COAST

Meaning to cheer May up, perhaps, the grandmother announces to her granddaughter that she’s thinking of selling up. And although she looks down on tourists, she would like to go to the coast to visit her son (May’s Uncle Lewis).

May tells her grandmother she’s too old. She’ll probably die of a heart attack. The other woman is pragmatic and says well they could truck her back home in a refrigerated vehicle alongside the chilled fruit and vegetables.

The granddaughter is suspicious of her grandmother, far more likely to play tricks on her than to promise anything good.

HOME LOOKS SUDDENLY DIFFERENT NOW

A customer arrives; the grandmother serves him and chats. Meanwhile, something in May’s world has changed forever, now that her grandmother has mentioned the possibility of a trip to the coast.

Alice Munro describes the same vista again, like she did in the opening paragraph, only this time the environment takes on an ominous vibe.

MAY LISTENS TO THE CUSTOMER TALKING TO HER GRANDMOTHER

The customer drinking out front is on his way to see a friend with terrible insomnia. As an amateur hypnotist, he hopes to solve this friend’s sleeping problems.

The grandmother replies that she doesn’t believe in all that superstitious stuff, but May interjects. She’d like to know more. She’s not allowed to talk to strangers in the store, but she’s feeling bolshy today. The man explains what hypnotism is:

It’s just like you put a person to sleep. Only they’re not really asleep, do you follow me honey? You can talk to them. And listen—listen to this—you can go way deep into their minds and find out things they wouldn’t even remember when they were awake. Find out their hidden worries and anxieties that’s causing them the trouble.

“A Trip To The Coast” by Alice Munro

The grandmother, listening, declares she could never be hypnotised. As a person who prides herself on her individualism, this feels entirely in keeping with the character.

Let’s pause for a moment here to talk about hypnosis, or hypnotherapy as it takes place in a psychotherapist’s room. Is it bunkum, like the grandmother says? Could this grandmother be immune to hypnotism, or is everybody susceptible? What does fiction get right and wrong about hypnotism, or hypnotherapy?

HYPNOTHERAPY AND HYPNOSIS (IN AMERICA)

The hypnosis in Alice Munro’s story is what professionals call ‘stage hypnosis’, which has influenced how people think of the tool.

STAGE HYPNOSIS

Typically how it works:

- hypnotist gets 20 people up on stage after suggesting something to the crowd in their seats (e.g. put your hands together, now you can’t pull them apart, anyone who can’t pull them apart come up on stage)

- maybe 5 will really follow suggestion deeply

- the remainder are sent back to their seats

- the people on stage do ridiculous things for audience amusement

- a few people want to be part of the act, and can fake being under the spell

- stage hypnotists don’t actually care too much about the fakes — it’s all part of the show

- in the end, hypnotherapy and hypnosis access the same “altered state”

HYPNOTHERAPY

Hypnosis isn’t the preserve of psychologists and psychotherapists. Anyone can learn the techniques and sell their services to, for example, increase creativity or something. Because they only have this one skill, they’ll try to apply it to everyone even if it’s not the best therapy.

In contrast, a medically trained professional may use hypnotherapy as one tool in a much bigger toolkit.

Milton H. Erickson is the most important figure in American hypnotherapy. His legacy can be seen in the Ericksonian Hypnosis Institute in Arizona.

Erickson’s therapy is similar to the techniques of Dan Brown.

- empowers the client

- is far more powerful than a placebo

- the client knows what they need

- hypnotherapy simply helps them access this self-knowledge

- sessions are based on trust

- being ‘under’ is similar to the state of being fully immersed in a movie — you feel you’re there

- Pierre Rainville (Montreal) is an expert on what hypnosis does to the brain

- a series of brain changes happen

- initially: activity in the left frontal lobe as people attend to whatever the suggestions are

- then: the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex disengages

- the ACC (the part of our brain that motivates us) engages at the same time

- basically: people give up judging/caring what’s happening, and become very open to suggestion

- finally: different parts of the brain activate in response to suggestion e.g. a transfer of activity to the non-dominant hemisphere

- it’s not ‘sleep’

- people almost never fall asleep (in some cultures this is a form of embarrassment)

- people are mostly aware of what’s going on around them, but it’s like your brain is shut off in a light sleep, like that twilight zone between wakefulness and sleep

- if you tell them to ‘wake up’ when you snap your fingers, they will, which means they are integrating suggestions

- on the part of the client, the feeling is a phenomenon known as dissociation

- dissociation is a state of mind which lets you be two places at once

- every child is capable of this (a necessary way to escape the constant control of adults)

- in fact almost every adult has retained this ability

- we are never of one mind

- under hypnosis, people create their own scenes and interpret the world to ourselves

- we then convert that information to fit our own meaning system

- hypnotherapy works because part of us feels one way, part of us feels another e.g. capable vs. helpless

- also, we all half know things

- the goal of hypnotherapy: to make the client feel empowered rather than victimised and alone

- (trauma victims will often say the worst part of trauma is the feeling of being alone)

WHAT IS HYPNOTHERAPY USED FOR?

- hypnotherapy is just one tool in a psychotherapist’s toolbox

- hypnotherapy can be helpful for managing physical pain e.g. at the dentist’s if the patient is allergic to novocaine

- it is also used to treat anxiety and a range of other mental and physical problems e.g. irritable bowel syndrome, insomnia, smoking cessation, weight loss

- the strongest research in support of hypnotherapy exists for acute and chronic pain (Mark Jensen)

- IBS also has a lot of supportive literature now

- Joe Green works on hypnotherapy and smoking cessation

- we know hypnosis used at the right time increases the effect size of psychotherapy by a large margin

CAN ANYONE BE HYPNOTISED?

No…

- if clients don’t trust the hypnotherapist, it won’t work, so people with trust issues have more difficulty

- not every client is able to engage in hypnotherapy but generally, children have a much easier time

- the ability to engage in hypnotherapy is about trust (or lack thereof); not personality

- there’s no such thing as ‘a personality type’ which is resistant to hypnosis

- when hypnotherapy won’t work: in clients who don’t rely on natural language but instead are relying upon their personal language (that framework is from Lacan)

- about 10 per cent of people don’t seem to respond

- about 10-15% of people at the other end of the bell curve are highly hypnotisable

- for the most part, people won’t do what they don’t want to do under normal circumstances

- e.g. if someone is told to cluck like a chicken they won’t do it unless they’re willing to go along with it

- this is measured by hypnotising someone and give them a series of about 12 suggestions, then measure by how many suggestions are followed (not an especially effective way of measuring hypnotisability)

- hypnotherapy is unsuitable for psychotic clients, as psychotic individuals are also using language in their own way rather than as a social connector,

- another group for whom hypnotherapy must be used with care: people who have learned to use dissociation as a response to trauma in their early childhood to the point where they dissociate at the drop of a hat (avoid regressing them to early childhood)

IS HYPNOTHERAPY WIDELY ACCEPTED AMONG THERAPISTS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS?

- the popularity of hypnosis has waxed and waned over the decades and this cycle continues

- in the 1800s it was regularly used as a pain management tool

- but it became far less popular after the advent of ether

- ether is a lot more efficient

- it came back for a while

- and then graduate schools became a lot more interested in mindfulness techniques, and the popularity of hypnotherapy has waned again

- however hypnotherapy is on the wax again due to advances in brain science

- in America Harvard psychology students are taught hypnotherapy but this is considered unusual

- it remains quite difficult to find a healthcare practitioner who has been trained in hypnotherapy

- general treating psychologists do have tools which are quite similar to hypnotherapy at their base: e.g. progressive relaxation (the foundation of hypnosis: scanning the body, counting and so on)

- hypnosis has classical conditioning at its core but once learned, it is far more efficient at getting the client into the desired state (e.g. a pain management client falls into it when they feel a nurse tapping them on the shoulder, when otherwise progressive relaxation might take most of an hour)

- there’s much similarity between advanced hypnosis and guided psychedelic therapy, becoming more popular these days

SELF-HYPNOSIS

- yes it’s possible to teach yourself self-hypnosis

- you’re tricking the logical part of the brain, coming out of automatic functioning

- there are several ways of capturing attention, so it’s easier if someone else does that

- it takes practice to do this yourself

- until you get skilled at it, it’s more effective coming from a trained hypnotherapist

- smartphones are helpful as clients can record the therapist putting them into a trance (inductions)

- can play back the recording on days they don’t have a session

- playing the recording back daily strengthens the effects (backed by research)

- it’s also possible to do hypnosis remotely but it’s not quite the same — practitioners like to do things like match their breathing to yours, becoming really in tune with your body, noticing small things about your body language

- we don’t really have a ‘self’

- what we think is a self is really a transient process

- we get into trouble by focusing on the past and the future, both illusions of the mind

We don’t see the world as it is, we see it as we are.

Anaïs Nin

QUACKERY

- stage hypnotists can make outlandish claims about what hypnosis can achieve

- e.g. regressing you to a ‘past life’ under hypnosis

- a researcher called Mark Nash (University of Tennessee) explains how people under hypnosis appear to come up with stories about their so-called past lives

- this is a religious phenomenon

- “everyone seems to go back to the seventeenth century and be run over by a carriage”

- this shows that our idea of a past life is influenced by the collective notion of what ‘history’ looks like (no one goes back to being an amoeba)

- under hypnosis, most people experience very vivid imagery

- imagined things feel very real

- this aspect of hypnotherapy led to awful practices which were eventually critiqued in the 1990s when people started remembering things such as repressed sexual abuse

- wealthy people accused of abuse built a case to make it seem as if hypnotherapists had suggested everything

- however, it is possible to take someone back to an earlier time in their own life — a very useful technique to take clients back to an earlier, happier time where they can integrate those happier resources into the present

- like any powerful tool, hypnotherapy can be misused and indeed has been misused in gay conversion therapies for instance

- in fact all memory is subjective

- hypnotherapists understand this keenly

- memory has never been a recording device and a person’s memory should never serve as the basis of a law suit

- in fact psychotherapists still believe permissive hypnosis to be a useful tool to change a client’s internal system, but not to produce information as proof in a courtroom

- effective psychotherapists don’t suggest; they follow the client’s lead

EIDETIC IMAGERY

- eidetic imagery: an unusually vivid subjective visual phenomenon. An eidetic person claims to continue to “see” an object that is no longer objectively present

- there’s a theory that we all have eidetic imagery before spoken language as children

- one study showed that when adults were regressed to children under hypnosis they were better able to achieve certain tasks

- adult eidetic memory is very rare, but researchers have observed that it occurs more frequently in autistics e.g. Stephen Wiltshire, who can draw detailed cityscapes from memory

WHAT DOES POP CULTURE GET WRONG ABOUT HYPNOTHERAPY?

- the cartoon imagery associated with hypnosis: a swinging stopwatch, spirals in the eyes

- (the watch is simply a device to capture people’s attention — there’s nothing magical about it)

- storytellers love the trope in which hypnotherapists suggest things which clients act upon

- ‘permissive hypnosis’ (mentioned above) is now outlawed in countries such as Canada, and can’t be used as legal evidence in the USA, but storytellers find it useful to move plots along

- you don’t need to be inducted by someone else; you can learn techniques for yourself e.g. at the dentist or for during childbirth, but we rarely see self-hypnosis on screen

References: It’s Not Just In Your Head podcast: #87: Hypnotherapy—Does it work? and Hypnosis in therapy — pain management for the body and mind, with David Patterson, PhD, Speaking of Psychology podcast

WHAT WAS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD OF HYPNOTHERAPY WHEN ALICE MUNRO WROTE THIS STORY?

Munro has presented us with a self-described amateur stage hypnotist, which avoids coming down on any one side about the efficacy or otherwise of hypnosis as a therapeutic tool.

PROJECT MKULTRA

An interesting bit of history to look up: an illegal human experimentation program undertaken by the CIA in the 1950s. The aim of this project: to develop procedures (e.g. hypnosis) and identity drugs which could force confessions out of captured enemies. This project lasted for 20 years, between 1953-1973. The USA was very scared of communism.

Of course, this is a form of torture and, no surprise, it started in the WW2 era in Japanese facilities and Nazi concentration camps.

In short, people living through the 1960s had good reason to be suspicious of anyone dabbling in the dark art of amateur hypnosis. Project MKUltra wasn’t officially revealed to the public until 1975. But many people were killed. We don’t know how many. Many more had their brains (and lives) ruined. This must have been an ‘open secret’, much as having queer relatives was an open secret, or the proliferation of abortion, or the existence of abusive priests was an open secret. People half know things.

Canadians such as Alice Munro had special reason to be wary of anything related to brainwashing because WW2 was fresh in the collective memory.

Notably, the CIA exported some of their experiments to Canada. A British psychiatrist by the name of Dr Cameron was paid a motza by the USA to travel from New York to Montreal each week, ostensibly in an attempt to cure schizophrenia by erasing memories and reprogramming the psyche (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind style).

I say ‘ostensibly’ because Naomi Klein argues in The Shock Doctrine that he was really there to extract information from ‘resistant sources’ by means of torture, but under the guise of science.

Of course, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is speculative fiction. No one can blast away old memories and replace them with new ones. However, it is possible to blast away old memories using extremely high doses of LSD and electroshocks.

There’s a 1998 Canadian four-hour miniseries about this upsetting episode of Canadian psychiatric history called The Sleep Room.

Basically, every horrific story you’ve ever heard coming out of a psychiatric ward from the mid 20th century, times it by ten and that’s what this torturer Dr Cameron was up to. (And if you’ve no idea what I’m talking about, I recommend the autobiographies of New Zealand author Janet Frame. These practices were exported all over the West.)

MAY CHALLENGES THE MAN TO HYPNOTISE HER GRANDMOTHER

To borrow from Thelma & Louise, something has flipped over in May, and until now her grandmother has seemed undefeatable. But today she would love to see her own grandmother hypnotised. She doesn’t for one moment think her grandmother is hypnotisable, but it would break the monotony of the afternoon in Black Horse if he at least gave it a damn good go.

The little man doesn’t disappoint. (He is described as ‘the little man’ in a deprecating way, and also because he is small in stature.) He tries to hypnotise the grandmother with a shiny bottle opener.

Amateur stage hypnosis is exactly the performance we’ve been expecting. (Notice how you’re just as in on it as May.)

What else are we expecting? We’ve already seen that this burlesque witch of a grandmother is a trickster. I know what I’m expecting. I think she’ll pretend to be hypnotised just as she pretended to be stone cold dead that time.

Sure enough, this grandmother does not disappoint. She falls flat on her face, on the counter.

The amateur hypnotist exclaims that this is not his fault, this has never happened before. He runs out of the store, gets in his car and zooms away, leaving May alone and speechless out front.

May stays outside so long that the day starts to darken and a little rain begins to fall.

CLIFFHANGER ENDING

Cruelly, Alice Munro does not let us back inside the house to check whether the grandmother was faking or really dead. We could make a list in two columns: She’s dead/She’s not dead. There’s plenty of evidence the grandmother is faking, but also some evidence she is not. In any case, the grandmother’s possible death is not the crux of the story: May’s unmoored aloneness is. Like the ending of The Wrestler, readers can deduce that even if the grandmother has not died on this particular day, she will be dying like this someday very soon. And this is how May will feel. We can also reliably deduce that the pair of them won’t be going to the coast.

This lack of knowing is nothing compared to what May must be feeling if her grandmother really is dead. She was promised a trip to the coast, and now she won’t be getting it. Her own mother is unlikely to take her; her own mother refuses to leave the natal home despite everything pointing to her being better off in town. (Hazel wouldn’t have to drive 60 miles every work day. Her friends and social life are all in town.)

She sat with her legs folded under her looking out at the road where she might walk now in any direction she liked, and the world which lay flat and accessible and full of silence in front of her.

“A Trip to the Coast” by Alice Munro

THE VICTORIOUS GRANDMOTHER

The final sentence underscores that the grandmother is ‘victorious’. Why victorious? Not just because she scared the bejeezus out of the so-called amateur hypnotist. She has died suddenly, without needing to rely on anyone, even her own daughter and grand-daughter who presumably are expecting to have to help the old lady as she enters further into old age.

The hypnotist is a good foil (contrast) character because hypnotism requires a client who is trusting. The grandmother is pretty far from trusting. She doesn’t even trust her granddaughter at the local swimming hole with two other friends. Her individualism is actually toxic, and toxic individualism very often comes from a background of trauma.

OTHER STORIES FROM DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast“

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.