**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

Alice Munro isn’t known as a feminist writer, but she is. Alice Munro isn’t known as a queer writer, either, but she has always been a keen observer of humans, and in every small town, queerness exists. Alice Munro therefore wrote about queer experiences, probably without meaning to sometimes.

I’m about to argue a queer subtext for Red Dress—1946. But even without a queer subtext, “Red Dress—1946” is a strong story. Here’s a highly favourable consumer review of “Red Dress” which epitomises a straight take:

My favourite story [in the Dance of the Happy Shades collection] is about a girl in grade nine attending her first high school dance. She’s been feeling awkward since she started, is worried that her only friend isn’t really her friend, and wearing a dress her mother made that she doesn’t really like. She doesn’t want to go, but can’t see how to opt out. When she arrives at the dance, after a few rounds of being passed over by the boys looking for partners, she hides in the bathroom. She meets an older girl who is an athlete and generally popular.

While they smoke in the janitor’s closet, our narrator begins to connect with this older girl, who says a lot of the things she’s thinking out loud, and echoes her dislike of much of the high school social mores.

The girl invites her to a diner for a cup of coffee and to keep talking. But on their way through the gym to get their coats, a boy asks our narrator to dance, and she waves the girl off, feeling like she can’t say no to the boy, and equally relieved to be fitting in. It broke my heart.

a consumer reviewer

Nobody realizes that some people expend a tremendous energy trying to be normal.

Albert Camus

But there’s another, even more fascinating layer to this story. “Red Dress—1946” describes perfectly a common queer experience. The narrator is highly identifiable as a young asexual character living in a milieu six decades before the word asexual existed in reference to orientation.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE YEAR 1946

It is significant that Alice Munro included the year of the setting in the very title. The post-war setting of this story is crucial to our understanding.

WW2 opened new opportunities for young women. Young women now had models of how to live a non-starvation level life without relying on a white male income. Although working women earned a stingy proportion of a male wage, even for the exact same work, though repetitive and routine tasks were considered women’s work. The more intellectually stimulating jobs were kept for men. Despite all this, a single woman could live frugally, even without marrying. This was a huge step up from their grandmothers, for whom staying single was a poor economic decision, and no decision at all. For an independent-minded young woman of 1946, a teaching or nursing wage was her best bet.

For queer readers, there’s more to this story. The narrator of “Red Dresses—1946” will be living her entire life with the hermeneutical injustice of no word to describe her identity. No word, no concept, no fully realised self-insight, just the underlying feeling that something is wrong with her:

I have a red velvet dress, I did my hair in curlers, I used a deodorant and put on cologne. Pray, I thought. I couldn’t close my eyes but I said over and over again in my mind, Please, me, please, and I locked my fingers behind my back in a sign more potent than crossing, the same secret sign Lonnie and I used not to be sent to the blackboard in Math.

It did not work. What I had been afraid of was true. I was going to be left. There was something mysterious the matter with me, something that could not be put right like bad breath or overlooked like pimples, and everybody knew it, and I knew it; I had known it all along. But I had not known it for sure, I had hoped to be mistaken. Certainty rose inside me like a sickness.

“Red Dress—1946”

Without the words to describe herself, she settles on ‘something mysterious the matter with me’ and ‘sickness’.

Note that the story is set in 1946, published in 1968. The asexual movement was still three decades away at time of publication.

Lesbians were a little further ahead than aces, since being gay is about how you relate to others, whereas being asexual (and trans) is about how you relate to yourself. This means there’s nothing in the external world to hasten an epiphany. The narrator doesn’t quite identify with the older girl in the bathroom. She remains without a label to describe herself. There is no self-revelation to be had here. Instead, the ending illustrates how an young asexual woman is roped into the dominant (cis)heteronormative culture of compulsory dating, romance, marriage and sex.

There was a word for male-female mixed-orientation marriages back then: Lavender Marriages. However, with so-called lavender marriages, it was assumed one or both partners married as a method of deliberate concealment. In the case of orientations which did not yet have a name (or an exterior-world outworking), the concealment ran very deep: Even the people involved did not know this was their situation.

This is not an exclusively asexual story, of course. “Red Dress—1946” explores how marriage was compulsory for everyone, and how marriage was an economically, socially, politically prudent “decision” especially for women (who weren’t making choices in a vacuum).

WHAT HAPPENS IN “RED DRESS—1946”

We meet our 13-year-old narrator as she is preparing for her first Christmas Dance. She is clearly baffled by the highly sexual culture around her. She longs for a return to childhood, when things made sense.

I looked at [the noughts and crosses etched into the wallpaper] and longed to be back safe behind the boundaries of childhood.

“Red Dress—1946”

All of the other girls have become boy-obsessed lately. Why?

It’s a very common asexual experience to take a great interest in sex as an information gathering exercise, without a single thought to what you, yourself, want. This experience is common also to young people (especially girls) growing up in a sexually conservative culture where pleasure leads to the devil, so can sometimes be difficult to parse:

We read articles on how to make up our faces to accentuate our good points and how to carry on a conversation on the first date and what to do when a boy tried to go too far. Also we read articles on frigidity of the menopause, abortion and why husbands seek satisfaction away from home. When we were not doing school work, we were occupied most of the time with the garnering, passing on and discussing of sexual information. We had made a pact to tell each other everything. But one thing I did not tell was about this dance, the high school Christmas Dance for which my mother was making me a dress. It was that I did not want to go.

“Red Dress—1946”

Things are all the more complex for the narrator of this story because of her social and generalised anxiety.

Her best friend has a genuine interest in boys and the pair are drifting apart. The narrator is baffled by the other girls and their strong interest in boys, none of whom seem particularly appealing.

Indeed, the boys in Science class are outright misogynistic, picking on their young female teacher because they can.

But what was really going on in the school was not Business Practice and Science and English, there was something else that gave life its urgency and brightness. That old building, with its rock-walled clammy basements and black cloakrooms and pictures of dead royalties and lost explorers, was full of the tension and excitement of sexual competition, and in this, in spite of daydreams and vast successes, I had premonitions of total defeat. Something had to happen, to keep me from that dance.

“Red Dress—1946”

Relatable ace experience:

- You would rather fall off a bicycle and injure yourself than go to a dance

- You would rather suffer from bronchitis than go to a dance

- You would rather smear your naked chest with snow and turn blue with cold than go to a dance

- You would rather sleep all night in wet flannelette pyjamas than go to a dance

- You would rather die under the ashes of Vesuvius than go to a dance (a volcanic metaphor which is surely saying something about lack of sexual roiling)

However, there’s nothing wrong with this thirteen year old. This is a strong and affirming asexual message which says to pre-sexual girls and aces alike: There is nothing wrong with you for not wanting what everyone else in school wants. It’s okay to take interest in reading about Pompeii on the couch at home. You’re hurting no one.

Still, there’s huge pressure to go. For one thing, she’d like to be taken seriously. Her mother doesn’t treat her as an adult. It is common for people to start treating you as an adult only when you start experiencing certain ‘adult’ things e.g. having a romantic partner.

The mother treats the friend as an adult but her daughter as a child.

This is a recognisable dynamic to most people, I’d say. If you’ve ever learned to drive a vehicle, perfectly well, you may have noticed your parent unable to relax in the passenger seat. After all, they remember changing your nappies.

This phenomenon is even more recognisable to aces, whose childhood friends will appear to mature faster.

By the by, the gap between how a parent treats their own child compared to how they treat other people’s is also very recognisable to the children of alcoholic and other addicts. Alcoholics are so often excellent with strangers… but when it comes to their own families? Terrible. Strangers offer a chance for a do-over. (If you loved Mickey Rourke’s character in The Wrestler and just thought his estranged daughter should give him a chance, this is why she reacted as she did.)

So our narrator takes comfort in preparing for this damn dance. ‘I wanted the protection of all possible female rituals’. She is startled by the dress, which makes her look both sexually mature and childlike at once. Dressed like this for consumption, she does not feel like herself.

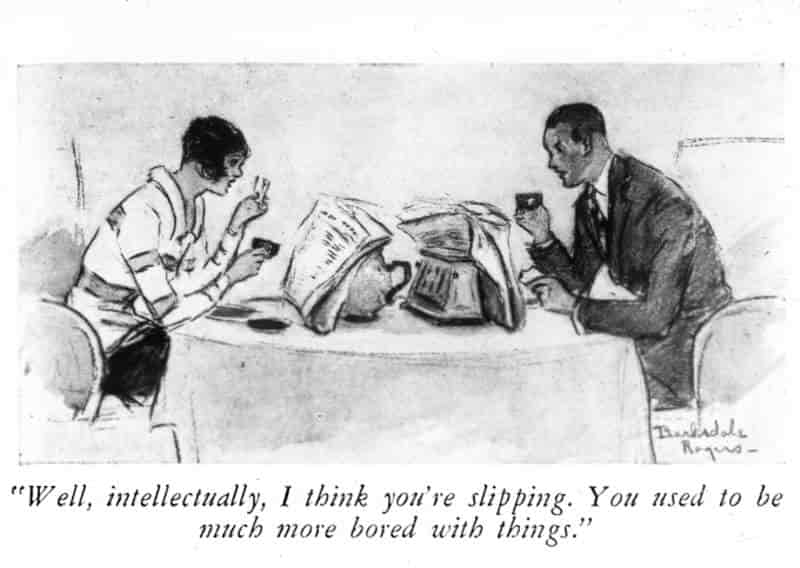

At the dance, no one really seems to be having much fun anyway. What is all the fuss about? The other girls look positively morose. Are they really having fun? Or is this just one big conspiracy? Does this Emperor have no clothes?

In the moment, though, the thirteen-year-old main character idealises this boredom.

The girls stood beside [their beaus], resting their hands casually on male sleeves, their faces bored, aloof and beautiful. I longed to be like that. They behaved as if only the—the older ones—were really at the dance, as if the rest of us, whom they moved among and peered around, were, if not invisible, inanimate…

“Red Dress—1946” (The invisibility is highly relatable to aces, as well as to anyone who arrives at the rites of adulthood later than their peers.)

She retreats to the relative solitude of the bathroom. There, an older girl with the (ironically?) symbolic name of Mary Fortune who also seeks refuge from the compulsory heterosexuality of the dance hall. Mary Fortune recognises her kin and invites the younger girl to the janitor’s closet for a (masculine and very grown-up) cigarette. Mary conveys to our narrator her plans to remain single, earning her living as a P.E. teacher. She is very likely some kind of queer herself (aromantic ace or Sapphic). In the strongly amatonormative, patriarchal culture of the 1940s, a girl’s desire to remain single for life is enough in itself to justify a queer reading.

Aaand, this is exactly how the queers find each other in school. Queers sniff each other out, often meeting mentors and friends from different year levels due to rarity. Mary invites the narrator to Lee’s, where they can chat and have hot chocolate, but the narrator never makes it out of the dance hall. She is grabbed by a boy who wishes to dance with her.

It was Raymond Bolting from our class, whom I had never talked to in my life. He thought I meant yes. He put his hand on my waist and almost without meaning to, I began to dance.

“Red Dress—1946”

She’s been picked. If she keeps company with Mary Fortune, she’ll consistently feel there’s something wrong with her. But if she dances with this boy, she can tell herself she’s normal. For now, this is a much more comfortable place to be. So she submits, forgoing her opportunity to know Mary better, and find in her a role model of a queer girl who has formulated a plan for her own life.

The boy walks her home, talking about a sport the narrator knows nothing about. The evening ends in the most unromantic way possible: The evening is cold and they develop runny noses. The narrator finds a possibly used tissue in her pocket and tears it in two so they both have something to wipe their noses on. When the boys leans forward to kiss her, he too is caught up in doing what’s expected at the expense of what he probably (doesn’t) want.

Then he turned back to town, never knowing he had been my rescuer, that he had brought me from Mary Fortune’s territory into the ordinary world.

“Red Dress—1946” (Mary Fortune’s territory = the queer margins of society.)

The final sentence is a ‘happy for now’ ending. In the social milieu of 1946, an asexual young woman could do okay, until marriage. It was expected girls remain chaste until then. But after marriage, she would be in trouble. She would now be expected to perform sexually and produce children, many 1950s children to aid in the war recovery. That final sentence makes perfect sense with an asexual reading.

Now let’s turn to more ways in which “Red Dress—1946” is relatable to anyone, queer or not, especially to women.

PERFORMATIVE FEMININITY

Another story in this collection is all about the psychically damaging effect of performative femininity. (See: “The Time of Death“, which is not just about the death of a little boy, but also about a sort of emotional numbness which takes women over due to what these days we call compassion fatigue.)

Looking through vintage texts, it doesn’t take long to understand that the “Smile, Baby!” phenomenon critiqued by contemporary feminists is very, very old. I would love to know when women were first required to start smiling as an expression of compliant femininity. We can’t use vintage photos as a guide, because there were a few smiles to be found in the early years of photography, it took until the 1920s and ’30s for smiles to start becoming the standard expression in photographs.

For more terrible 1930s dating tips for single women dating men, see the collection at Rare Historical Photos, in which we are reminded that a woman’s place in the early 20th century was to exist in deference to men. Alice Munro’s example of Advice To Young Women is spot on in her rendition:

I remembered an article Lonnie and I had read, which said Be gay! Let the boys see your eyes sparkle, let them hear laughter in your voice! Simple, obvious, but how many girls forget! It was true, I had forgotten.

“Red Dress—1946” (The ‘it’ of the last sentence refers to the forgetting part. It is vaguely comical that the narrator has seized on that part of the advice. In any case, if a boy breaks off a dance halfway through rather than treating her with kindness and consideration, her media consumption has very much taught her: It’s her fault. She’s doing something to repel boys.)

My eyebrows were drawn together with tension. I must look scared and ugly. I took a deep breath and tried to loosen my face. I smiled. But I felt absurd, smiling at no one.

“Red Dress—1946” (Another ace Easter egg: It does feel absurd performing sexuality when there’s no object of your affection. It’s absurd anyway, but aces are very well-placed to feel the absurdity keenly.)

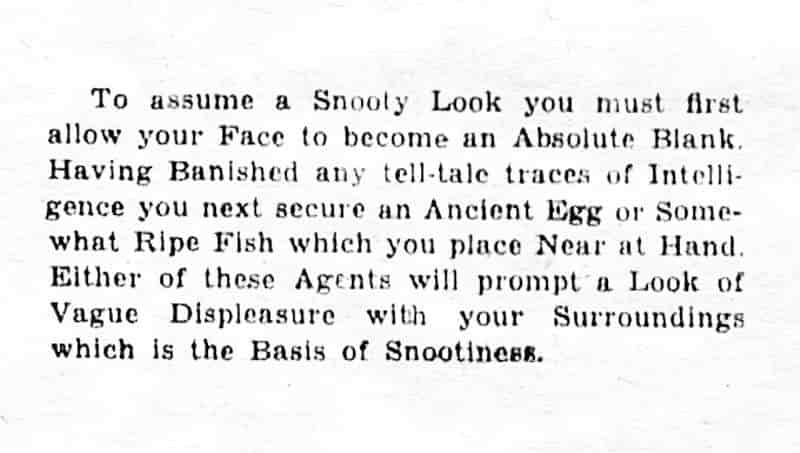

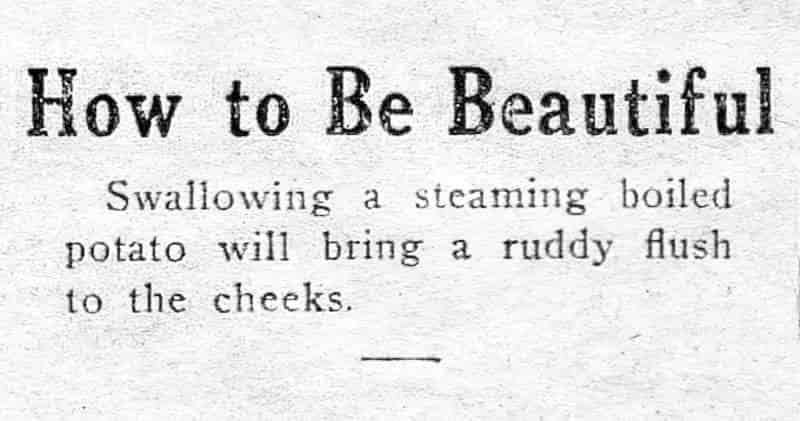

It’s reassuring to note that, even in the early part of the 20th century, women were hardly oblivious to the ridiculous beauty and performance standards required of them. Here’s a nice little clapback:

And here’s another, perhaps:

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DRESSES

The dress of the title is significant. Skirts and dresses have long been synonymous with girl- and womanhood (an example of metonymy). This is evinced in idiomatic expressions such as ‘skirt chaser’. (‘Suit’ is the clothing metonym for ‘man’, evoking someone powerful and in charge.)

Skirts: Fashioning Modern Femininity in the Twentieth Century

While the story of women’s liberation has often been framed by the growing acceptance of pants over the twentieth century, the most important and influential female fashions of the era featured skirts. Suffragists and soldiers marched in skirts; the heroines of the Civil Rights Movement took a stand in skirts. Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe revolutionized modern art and Marie Curie won two Nobel Prizes in skirts. When NASA put a man on the moon, “the computer wore a skirt,” in the words of one of those computers, mathematician Katherine G. Johnson. As women made strides towards equality in the vote, the workforce, and the world at large, their wardrobes evolved with them. They did not need to “wear the pants” to be powerful or progressive; the dress itself became modern as designers like Mariano Fortuny, Coco Chanel, Jean Patou, and Diane von Furstenberg redefined femininity for a new era.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell’s Skirts: Fashioning Modern Femininity in the Twentieth Century (St. Martin’s Press, 2022) looks at the history of twentieth-century womenswear through the lens of game-changing styles like the little black dress and the Bar Suit, as well as more obscure innovations like the Taxi dress or the Pop-Over dress, which came with a matching potholder. These influential garments illuminate the times in which they were first worn―and the women who wore them―while continuing to shape contemporary fashion and even opening the door for a genderfluid future of skirts. At once an authoritative work of history and a delightfully entertaining romp through decades of fashion, Skirts charts the changing fortunes, freedoms, and aspirations of women themselves.

New Books Network

The colour of the dress is also significant. The redness and the velvet suggest sexuality and sensuality. The narrator is not ready to serve as a vehicle for this. As contrast, her best friend, Lonnie is associated throughout the story with the colour blue, starting (almost comically) with the narrator idealising Lonnie being a ‘Blue Baby’ (a serious medical condition of newborns). The red and the blue are almost complementary colours. In any case, they are very different, which shows how different these two thirteen-year-olds are becoming. United in childhood, their different experience of adolescent sexuality is enough to divide them, leading to loneliness on the narrator’s part.

Even the making of the dress is a metaphor for failing to fit in, both in an individual sense, and more broadly, since the rules of gender were in great flux:

Whenever she could [my mother] tried to skip basting and pressing and she took no pride in the fine points of tailoring, the finishing of buttonholes and the overcasting of seams as, for instance, my aunt and my grandmother did. Unlike them she started off with an inspiration, a brave and dazzling idea; from that moment on, her pleasure ran downhill. In the first place she could never find a pattern to suit her. It was no wonder; there were no patterns to match the ideas that blossomed in her head.

“Red Dress—1946”

This image of a mother sewing epitomises the change that was happening to women from generation to generation. For the first time, there was a massive social gap between mothers and their daughters.

All the stories of my mother’s life which had once interested me had begun to seem melodramatic, irrelevant, and tiresome.

“Red Dress—1946”

Before there was choice, women were required to fit a pattern. Now, for the first time ever, mothers and their daughters could choose their own life ‘pattern’, but finding a life to suit you remained elusive, difficult and outright impossible if you had no models to go on. After all, ‘you cannot be what you cannot see’.

I had worn [my mother’s homemade] clothes with docility, even pleasure, in the days when I was unaware of the world’s opinion. Now, grown wiser, I wished for dresses like those my friend Lonnie had, bought at Beale’s store.

“Red Dress—1946”

Extending the ‘dress as a woman’s life’ metaphor, the narrator is starting to look outward, to the possibility of a life which is not ‘docile’ and domestic, towards possible industry, symbolised here with a store-bought, commercially made dress. When bff Lonnie says in her perfectly pitched way, “It’s beautiful,” she has already learned how to perform as adequately female. Only the narrator knows it’s fake. She’s that good. And so, Alice Munro has set up the main themes in the dressmaking scene:

- the changing fashions/patterns of how women can now live their lives

- dresses as a nuisance which some women are better at than others

- the requirements of performative femininity (women must be beautiful, look like they made a major effort, express themselves in affirming and encouraging ways when when they don’t mean it…)

WHEN DID WOMEN START WEARING TROUSERS INSTEAD OF DRESSES?

Let’s return to the symbolism of the dress, and its corollary: women’s trousers.

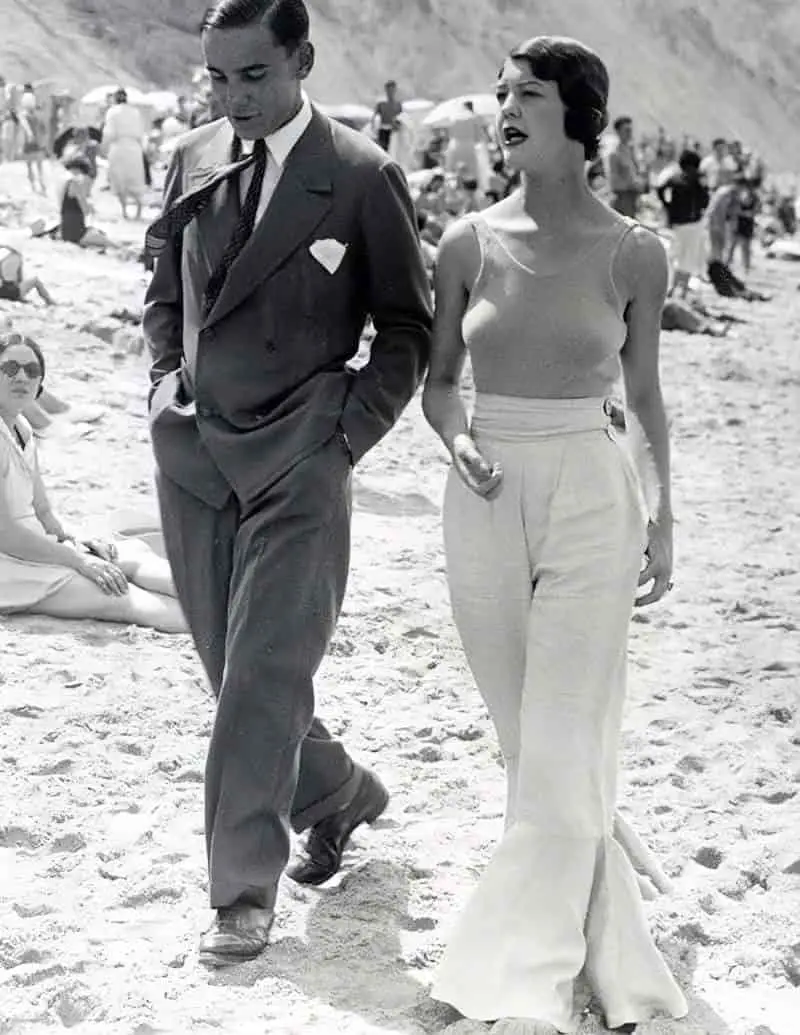

It’s important to note that women weren’t ordinarily permitted to wear trousers in the 1940s. Sure, wealthy women could lounge about in slacks at their country estates, or ride jodhpurs while riding their horses.

Coco Chanel introduced wide-legged trousers in 1922. Again, these were not regular attire. Starting out as wide legged trousers for wealthy ladies to wear while yachting, they made a transition to resort wear for shoreside or cruises.

Fashionwise, Coco Chanel is far better remembered for introducing the ‘little black dress’ (which was actually very modest by contemporary standards).

Farm women would wear trousers while doing manual labour on the farm. And during the war, women wore whatever was available. Factory workers were considered temporary larpers doing a male job while men were at the front, so factory working women wore trousers. (Moreover, skirts would have have been safety hazards in plants.)

Added to that, once the war in Japan was declared, silk stockings were no longer available. Pants were preferable in that case as it was unseemly for genteel women to show bare legs. We see evidence of this social regulation in Munro’s story:

I was embarrassed by the way my mother crept around me, her knees creaking, her breath coming heavily. She muttered to herself. Around the house she wore no corset or stockings, she wore wedge-heeled shoes and ankle socks; her legs were marked with lumps of blue-green veins.

“Red Dress—1946”

Despite the restrictions on women’s lower-body attire, this was all a major step forward compared to the 1800s, when scandalous women’s trousers were literally called ‘inexpressibles’. (Women would only wear trousers in very exceptional circumstances, e.g. they were athletes.)

But trousers did not become acceptable daily female attire until the 1970s. Even today, formal attire requires a dress; for a woman to choose trousers is to make some kind of statement, probably regarding her sexuality or gender or rejection of expected feminine fashion rules.

WHY HILLARY CLINTON WEARS PANTS

Hillary Clinton is famous for many things including, ridiculously, her pant suits. (She started wearing trousers after she was up-skirted, meaning she was sexually objectified and exploited after paparazzi took photos of intimate parts of her body and published them for public consumption.) Tellingly, this happened in 1995, but she only revealed this trauma publicly in 2022.

The former presidential candidate revealed that she wore a cream skirt suit during her visit to Brazil when photographers shot her from below.

“I was sitting on a couch, and the press was let in,” she told CBS Sunday Morning’s Norah O’Donnell. “There were a bunch of them shooting up.”

The Independent

DRESS AS METONYM FOR COMPULSORY, HIGH-MAINTENANCE FEMININITY

So when Alice Munro chose to draw our attention to dresses by using it in the title, this means something. It says something about the expectations of femininity. Whereas an objectifying expression like ‘skirt chaser’ turns women into skirts, Alice Munro’s short story highlights the 1940s reality in which high-stakes events requiring dresses evinced the stringent, high bar of performative femininity. Your dress communicated so much. It was vital to get clothing right. Too revealing, you’d be derided as that kind of girl. Insufficiently feminine and you’d be dismissed as a wallflower, chosen by no boy in a milieu which was short on men (due to losses in combat).

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946“

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.