If you’ve ever written something — especially fiction — then offered it up for critique, you’ll be familiar with this feeling: “Ah yes, I could see that problem for myself, deep down. But I didn’t really know it until you pointed it out.”

Common writing advice when creating character: Your main character should be wrong about something at the beginning of the story. If not, they don’t have room to change.

But let’s push a little more nuance into that.

First of all, Margaret Atwood has given plenty of thought to the deliberate (or adaptive) half-knowing of things, and how this can lead to totalitarianism:

We lived as usual by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance. You have to work at it.

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

A lot of being a poet consists of willed ignorance. If you woke up from your trance and realized the nature of the life-threatening and dignity-destroying precipice you were walking along, you would switch into actuarial sciences immediately.

Margaret Atwood

As with all knowledge, once you knew it, you couldn’t imagine how it was that you hadn’t known it before.

Margaret Atwood

The best way of keeping a secret is to pretend there isn’t one.

Margaret Atwood

It’s amazing how quickly people rolled over for the Patriot Act. You know they were scared enough so that they just said, “Oh, okay. If that’s how we solve it, fine. Just don’t tell me. You know I don’t want to know. Don’t tell me.”

Margaret Atwood in conversation with Bill Moyers

Here’s what others have said:

What I fear I avoid. What I fear I pretend does not exist. What I fear is quietly killing me.

Jeanette Winterson, The World and Other Places; from ‘The Green Man’

I can forgive ignorance but I can’t forgive a staunch commitment to it.

Unknown

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

Upton Sinclair

Heaven and earth, must I remember?

Hamlet, Shakespeare

If we have not yet succeeded — after how many centuries? — in eliminating from life the elements which plague us perhaps we need to question life more closely. Perhaps our refusal to face reality is the only ill we suffer from, and all the rest but illusion and delusion.

Henry Miller, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird

Henry Miller, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird

WHY WE STICK OUR HEADS IN THE SAND

Clearing the mind of fearful thoughts, rather than processing them, may sometimes be good for our mental health.

“When you avoid a thought by doing or thinking of something else, yes, you tend to attract that thought again,” says Mamat. “But we found that suppressing thoughts by making sure your mind is without any thought – for example by imagining a blank space or imagining pushing that thought out of your mind – can be beneficial.”

Suppressing worrying thoughts may improve our mental health: Rather than recalling and focusing on fearful thoughts, it might sometimes be useful to avoid these imaginings to boost our well-being and avoid symptoms of mental health conditions like depression or PTSD from New Scientist

TYPES OF HALF-KNOWING

We all half-know things. Let’s take that aspect of human psychology and apply it to our fictional characters. Some of the most interesting, character-driven stories feature characters who sublimate, ignore and repress.

- PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS: Characters do know something. They simply refuse to see it, due to other, deeply-embedded character flaws,

- PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS AT A CULTURAL LEVEL: culture that conspires to avoid them seeing. They crop their mental picture.

- PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS IN SCIENCE AND ACADEMIA: We half-know things because our vocabulary and cultural concepts lead us down a particular way of thinking, to the exclusion of all else. The trouble is, we think we know things well, because they have been studied for decades.

- HERMENEUTICAL INJUSTICE We half-know things because the vocabulary and cultural concepts simply do not exist.

Things that disappear when you look too closely often were never there in the first place: that’s how illusions and tricks of the eye work. Perhaps you’re thinking you’d rather be blissfully unaware, but ignorance is no guarantee of bliss. Illusions are unstable things that can crumble for all sorts of reasons and without warning, even if you studiously avoid looking at them.

Carrie Jenkins, What Love Is And What It Could Be (2017)

Ok, it’s time for a reality check.

@thewritertype

*checks reality*

Holy sh*t. Would not recommend.

WHEN DOCTORS GET SICK

Doctors must be in a great position to know when they themselves get sick, right? With all their medical training and experience, they would understand that whenever they see a symptom in themselves, they should take measures to get it checked out or make behavioural changes.

Well, not quite. Near the beginning of their illness, doctors do know what’s up… sort of. But doctors are extremely good at putting their own illness out of their minds.

I think almost all doctors, you develop this pretty profound separation and detachment from patients. To a certain extent, you have to do that to do the work. If you got deeply emotionally involved with every patient, particularly if you do a very dangerous surgery, as I did, you wouldn’t be able to do it. And also, you learn right from the get-go that the most frightening thing for a patient is a frightened doctor. And you often are anxious ’cause that’s the nature of the work. And you therefore have to pretend and deceive to a certain extent to radiate confidence and certainty when, actually, inwardly you don’t feel that. And of course, the best way of deceiving other people is to deceive yourself. So I think many doctors live in this sort of limbo of the us and them. The illness happens to patients, not to doctors. Anecdotally, I’m told that many doctors present their cancers very late, as I did, and I denied – at a very deep, unconscious level, I denied my symptoms for months, if not for years.

[…]

You ought to get it investigated to exclude cancer. And a combination of fear and reluctance to sort of cross over to the other side of the road and become a patient myself, men turn a blind eye to it. And, I mean, a lot of people do that with all sorts of things. You know, it’s a sort of – in medical language, it’s called hysterical dissociation or cognitive dissonance. You know it’s a serious problem, but part of you dismisses it.

After cancer diagnosis, a neurosurgeon sees life, death and his career in a new way, NPR Fresh Air interview with Dr Henry Marsh, Neurosurgeon

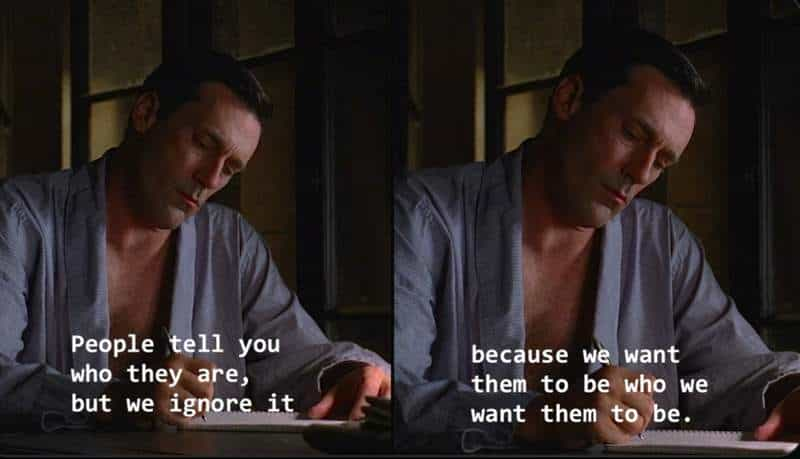

CHARACTERS WHO HALF-KNOW

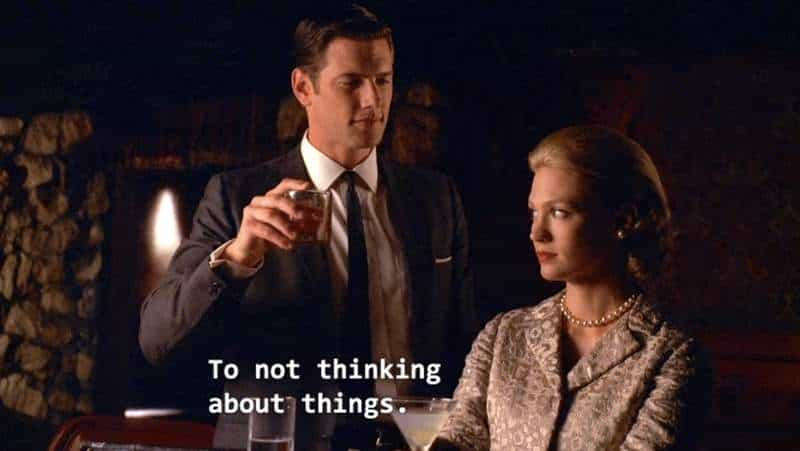

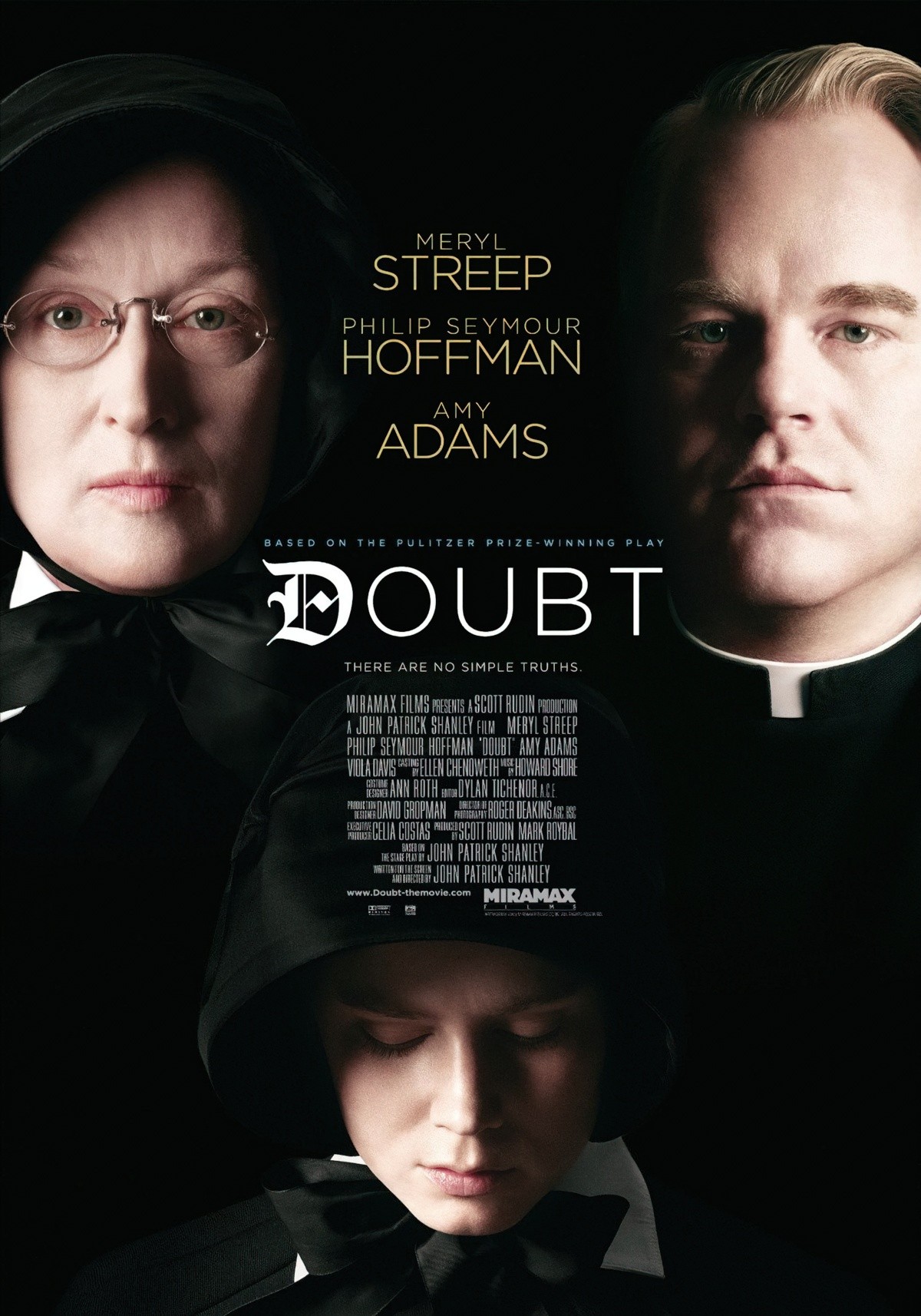

Recently I’ve analysed two films which do this beautifully: Doubt and August: Osage County (by coincidence, both starring Meryl Streep).

This feature of psychology is sometimes called sublimation or repression. Psychologist Daniel Goleman has named the phenomenon ‘psychic obtuseness’.

Shawshank Redemption clip on YouTube: “How can you be so obtuse?“

PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS

Rescue of Jews under the Nazis was, in psychological parlance, a “rare behavior.” […]

[But] bystanders who transformed themselves into rescuers held on to their innate empathy, while others who did not were swept up in the restructured social hierarchy with Aryans at the top and Jews at the bottom. Psychologist Daniel Goleman’s theory of “psychic obtuseness” is applicable to most people under Nazi terror. People notice certain things (the “frame”); everything else, especially those matters that cause anxiety or pain, are kept from consciousness. We crop our mental picture, says Goleman, and in so doing, ignore clues that indicate that things are amiss.

“The Rescuer Self”, Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS AT A NATIONAL LEVEL

Irish author Fintan O’Toole was born in 1958 and has seen much change over the course of his lifetime. He has written a book about the collapse of the Catholic Church, among other big changes, and has this to say:

Fintan O’Toole: Over the course of all of that change there is a story about a place which chooses not to know a lot of what’s going on within the society, and develops a kind of talent, really, for being deliberately unaware of things that are often staring it in the face.

Kim Hill: Yeah, the “knowing unknowing”.

Fintan O’Toole: Yeah, Donald Rumsfeld famously went on about the “known unknown”, with the known knowns and the unknown unknowns. I think there’s the Irish one: The “unknown known”. Of course, every society has it. We all have these capacities for collectively deciding not to acknowledge or process or recognise things that we really do know very well. They’re going on all around us. In the Irish case, I think a lot of this was very much linked in to something that people in New Zealand would be very aware of about Ireland, which is the history of mass migration. A lot of people in New Zealand are themselves Irish or have Irish [ancestry], you know, and that’s true in Australia, the United States, Canada, Britain of course, South Africa. Pretty much everywhere in the English speaking world. Irish people emigrated in huge numbers and that sort of mass migration does a funny thing to people, really. It sort of means that you live in two worlds at the same time.

When I was growing up, most of my father’s brothers and sisters lived in England. They were both us and not-us. When my cousins came over — it’s a short hop across the Irish Sea from where they lived in London or Birmingham to Dublin — but they were different. They had English accents. Were they really my cousins, or were they really foreign? If you think about huge numbers of people going to America, same sort of phenomenon, really. Not to mention going to New Zealand or Australia, where you would be literally never seeing them again.

So I think there’s a kind of tolerance for keeping things out of your mind because if you thought about it too much you’d probably go crazy. You can imagine what it must have been like for parents raising their children, knowing that they were raising them for export. For a long, long time, before modern air travel, you were raising them with the sense they would leave you at twenty. You might never see them again. So, habit of mind, really, of not knowing, and not wanting to know too much about what’s going on I think was deeply embedded in the society.

This plays out in the way Ireland begins to change in the year that I was born [1958]. There were lots of existential questions about whether [Ireland] could survive or not and it began this journey which has led us to being one of the most globalised societies in the world.

Fintan O’Toole: documenting the evolutions of modern Ireland, RNZ interview

Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

PSYCHIC OBTUSENESS IN FOLK TALE: “THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES”

My analysis of the tale is here.

“People are not stupid,” says Fintan O’Toole, about a corrupt 20th century Irish prime minister called Charles Haughey [basically pronounced ‘Hoy’]. In his book, O’Toole calls this guy “the master of hypocrisy”. In interview with Kim Hill he says: “It’s so obvious this guy is corrupt, and hypocritical. But he managed to get away with it.” His only means of income was his prime minister’s salary, yet he lived a luxurious life far in excess of what you’d expect. Everybody in Ireland could see it. The guy was against divorce, yet himself had a mistress, etc.

Australians will immediately recognise we have the same guy here. (Deputy prime minister in 2021.)

Fintan O’Toole describes the genius of such men. “If you make it so in-your-face, it becomes a natural phenomenon, like the River of Shannon or Galway Bay. Charlie Haughey is rich. You know, it’s just A Fact Of Irish Life. And he got away with “dissolute theft”, spending money that wasn’t his, leading the life of Riley with the Catholic church by his side.

WE SEE ONLY WHAT WE ARE READY TO SEE

It is very easy to get into a car and see only what we want to see.

Glassed In: How we choose not to see, Oregon Humanities

Not all traditions are the same when it comes to encouraging people to look the other way. Christian thought encourages its followers to look the other way in order to resist temptation. That’s how Christian husbands end up taking advice such as “guarding the eyes” to resist the temptation of other women who are not their wives.

But Susan Cain talks about Judaism deals with this differently. She came across a parable from the Kabbalah (from a mystical form of Judaism) while researching Bittersweet.

All of creation originally was an intact divine vessel. The vessel shattered. The world we’re living in now is the broken world following the shattering. But scattered all around us still are the divine shards, from when the vessel was still intact. And, one great way to live a life is to look around us and to notice the divine shards wherever they happen to land, then to bend down and pick them up. You will notice different shards from the ones I will, but we can all do our own gathering. […]

[The parable is] acknowledging the pain and the tragedy and the evil that exists in the world without having to become a prisoner to those things. So [the parable is] not telling us to look away from them and pretend that they’re not there, which I think is what our mainstream culture would tell us. It’s telling us they’re very much there, and we can admit that, tell the truth about that.

At the same time, we can turn in the other direction, in the direction of beauty and of love. We have the ability to turn in that direction. I find that parable to be such a relief! A relief to be able to tell the truth. Also just a great way to live, to know we always have that option.

How To Become Whole Through The Bittersweet With Susan Cain (author of Quiet and Bittersweet) at “The One You Feed” podcast

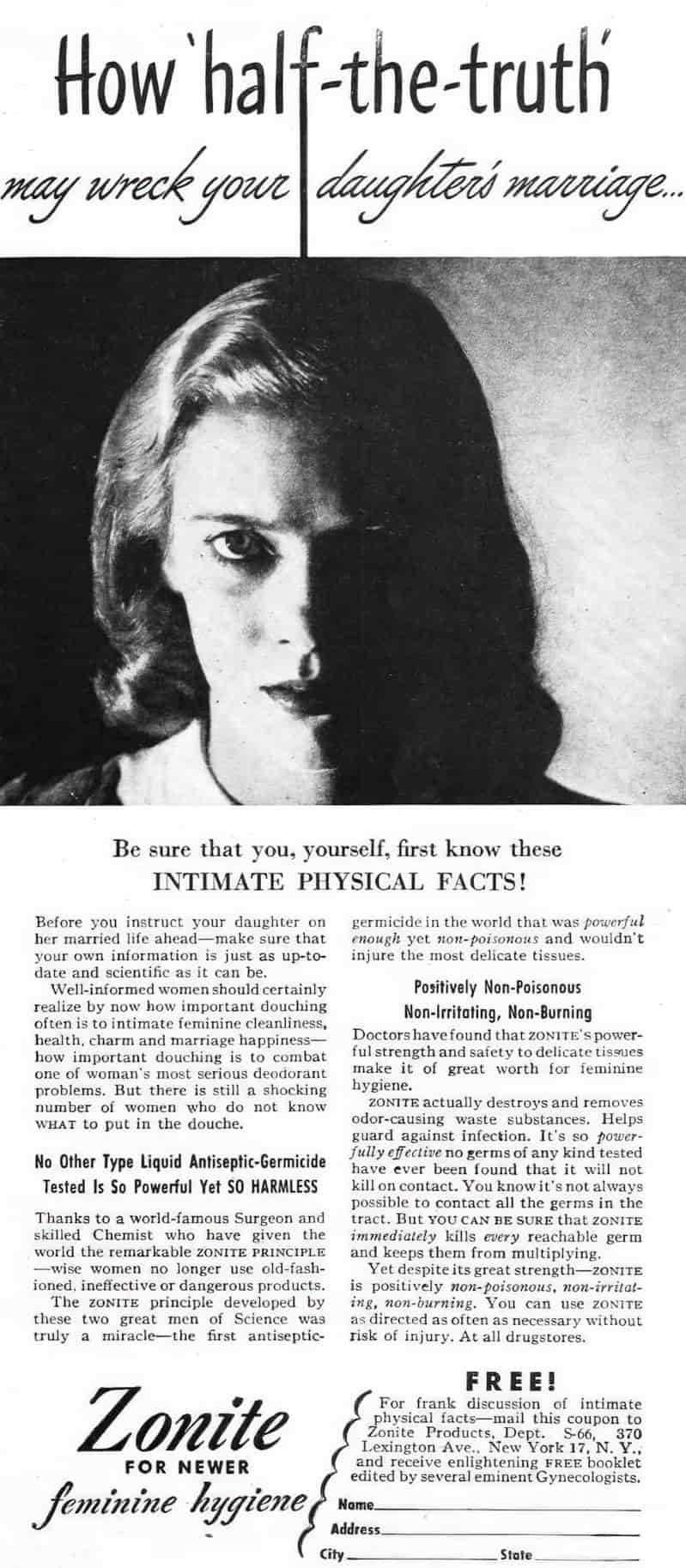

Moving away from story and back to real life, the ‘partial seeing’ is more reflective of reality. It’s everywhere. Here’s an example from the world of medicine, as uncovered by a feminist writer:

I think the bigger point here is that when you have a simple narrative that seems to explain a body part really well (like “ovaries come with all the eggs we’re ever going to have”), that really closes the lid on other explanations and other questions that could give you a tonne more information into those organs.

Ovaries are one example, but they’re certainly not the only example.

This kind of story is something I would find over and over again when I was working on the book, which looks at all sorts of pelvic organs, from the uterus to the ovaries to the v*gina to the cl*toris. And, there would be this dominant narrative of what this body part was for and what it represented and then there would be scientists coming up and saying, “Wait, we’ve never considered this. Or what if you look at it like this?”

Take the cl*toris, for example.

It has been called a minuscule phallus, or an underdeveloped penis, or a tiny nub, for hundreds and hundreds of years. And science has sort of minimised it in many ways.

Then a female researcher poked around and realised that the cl*toris is actually a much, much bigger organ than people had realised. It’s just that it’s sort of under the surface, waiting to be better studied. Or, take the v*gina for example. The word literally means ‘sheath’. It’s been treated as this tube for people’s penises, or like this place that needs to be kept really pure and physically clean.

Whereas in reality, the v*gina has many incredible qualities, including self-lubrication, and housing this ecosystem, this v*ginal microbiome, that helps protect the space between you and not you. It’s really an extension of your immune system.

The stories that we tell about our organs, they shape what we know, they shape what we research, and they shape what gets funded.

This is something scientists were telling me over and over again: When you study the human body, even though the human body is not changing, it’s been around for centuries and centuries, and you’ve seen these organs before, you really see what you expect to see. And you see what you are looking for. You kind of blur out the rest. And, what I think we need, is people that can fill in that background, who can focus on the parts that have been blurred out.

Can Ovaries Make New Eggs? Unexplainable podcast, Wed 17 August 2022

We need those people in the world of science, but in the world of storytelling, ‘focusing on the parts that have been blurred out’ is the storyteller’s main job.

Don’t explain. People only hear what they want to hear.

Paulo Coelho

FURTHER READING

Conservative politics works only when voters remain half ignorant of facts, and they know it.

My post on anagnorisis, the self-revelation part of a story which happens before the battle scene. I talk about the anti-epiphany. This is when a character seems to realise something but then decides they’d rather not know. So they go back to how they were before.

If you’d like to annoy corrupt Irish Prime Minister Charles Haughey, too late, he’s dead. In his honour, though, pick up a copy of The Lonely Girl by Edna O’Brien, part of a trilogy.

Haughey made a special trip to the archbishop to express his disgust at this book. That’s how much he hated it, so it must be really good.

The country girls are Caithleen “Kate” Brady and Bridget “Baba” Brennan, and their story begins in the repressive atmosphere of a small village in the west of Ireland in the years following World War II. Kate is a romantic, looking for love; Baba is a survivor. Setting out to conquer the bright lights of Dublin, they are rewarded with comical miscommunications, furtive liaisons, bad faith, bad luck, bad sex, and compromise; marrying for the wrong reasons, betraying for the wrong reasons, fighting in their separate ways against the overwhelming wave of expectations forced upon girls of every era.

The Country Girls Trilogy and Epilogue charts unflinchingly the pattern of women’s lives, from the high spirits of youth to the chill of middle age, from hope to despair, in remarkable prose swinging from blunt and brutal to whimsical and lyrical. It is a saga both painful and hilarious, and remains one of the major accomplishments of Edna O’Brien’s extraordinary career.

marketing copy for The Country Girls trilogy.

Header art was made using Midjourney AI.

“If you spend enough time blocking something out, built sturdy enough walls around it, then it’s almost like it didn’t happen.”

MEAN GIRLS, A HORROR STORY “Hannah-Beast” by Jennifer McMahon is a story about living with the Halloween prank that went too far

On Not Knowing is a suite of personal essays on the value of not knowing. Each begins with the phrase “How to” – “How to Catch a Minnow”; “How to Give Birth”; “How to Elude Your Captors.” Rather than the defensiveness of willful ignorance, this collection celebrates the defenselessness of not knowing yet—possibly of not knowing ever. Ultimately, this book shows how resisting the temptation of knowingness and embracing the position of not knowing becomes a form of love.

High Theory Podcast

The following story concerns a paper about a woman hears who voices asking her to get a CT scan. The voices claim she has a brain tumour. Her psychiatrist orders a scan to reassure her. But they actually find the tumour.

After her surgery the voices thank her for listening and disappear.