**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Day of the Butterfly” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro, included in her first short story collection Dance of the Happy Shades (1968). A number of the stories in this collection contain the message that when we do things as good citizens of a community, even when the act is ostensibly in service of another person, the act of ‘charity’ very often it serves our own psychological need. The recipient of our charity, attention or goodwill is secondary.

THE BUTTERFLY OF THE TITLE

The butterfly of this story is a blue tin toy which comes as a prize in a box of Cracker Jack snacks.

I had to look up Cracker Jacks, being unfamiliar with North American snack food. I learned it’s a type of salted caramel popcorn which came with tiny tin (later plastic) ornaments about the same quality as plastic soldiers, but smaller and even less useful and ornamental. Prizes were discontinued for good in 2016, following McDonalds, in an attempt to cater to Gen Z who apparently prefer digital rewards. (I doubt this is true. Look at the continued popularity of LEGO. I think Gen Z still likes items you can hold in your hand. They do require something better than a coloured shape, however.)

WHAT HAPPENS IN “DAY OF THE BUTTERFLY”?

If you’ve ever read The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes and Louis Slobodkin (1944), this story may feel familiar to you.

The point-of-view character is ten-year-old Helen, narrated in first person by her older self after she’s had time to reflect on a long-ago classmate called Myra who had been at the same school for two or three years before the narrator started noticing her. Myra is best known for leaving class to accompany her younger brother to the toilet. The younger brother has incontinence issues, which we might deduce has something to do with off-the-page trauma.

As a microcosm of the wider social rules of the community, boys and girls at school are strictly divided. The children believe if they set a foot in the wrong side they will be severely punished. Readers can extrapolate that this rule extends to ethnic divisions outside the arena of the playground. Helen is well-placed to see this social hierarchy as it is because she is an outsider herself. She lives outside town, and is only sent into town for schooling because the teacher at the nearby tiny school hasn’t been the same since menopause. (A terrible indictment on mid-life womanhood, I must say, but we must also accept the reality that menopause can be brutal.)

Myra Sayla was never included in the playground games, ostensibly because she had to take care of her younger brother, but the ethnicity difference is gradually revealed to be the main reason.

The young, inexperienced but well-meaning classroom teacher with the symbolic name of Miss Darling asks the other girls to include Myra. But this young teacher has glasses and braces and youth herself. She has neither the social influence nor the experience to facilitate such a delicate social manoeuvring. Instead, the emerging Mean Girls started mocking the teacher as well as continuing to exclude Myra, led by a Queen Bee character whose father owns the local store.

However, our narrator Helen has more empathy than the other girls, hence her role as the sympathetic viewpoint character. One morning, she arrives earlier than usual to school and encounters Myra. Alone with the outcast, Helen goes out of her way to be nice, realising in hindsight as an older woman recounting this tale that the “friendly” act of giving Myra the blue butterfly from the Cracker Jack box is an act of selfish charity which doesn’t have much substance—much like the empty calories of the caramel popcorn inside.

One day Myra disappears from class. It gradually becomes apparent that Myra is seriously ill. The adult narrator (and reader) can deduce that Myra has leukemia and won’t make it to her eleventh birthday.

So the well-meaning but inexperienced teacher decides the class will celebrate Myra’s birthday early by bringing presents to her hospital bedside. Although no one really cared to include Myra before, now they all rally round with the busyness of Doing Something Good, and Myra is required to perform the role of a good hostess as she unwraps the presents in her hospital bed, thanking everyone properly, dealing with gifts at the correct pace and with feminine displays of polite gratitude.

Helen lingers behind. She senses something more needs to be said. Perhaps because Helen once gifted Myra her Cracker Jack prize, Myra insists Helen take one of the gifts. A bossy nurse appears and chastises Helen for staying past visiting hours, and as an adult, Helen cannot remember saying a final goodbye to Myra.

She does remember the gift, not wanting to take it. And once she had it, she recalls the psychological burden of it.

The reader understands that Myra’s gift was hard to accept because it means nothing. She missed her chance to be a genuine friend to Myra. The chance was taken from her, because of the established social rules of that environment.

THE MOTIF OF EMPTINESS

Let’s catalogue where Alice Munro broaches the concept of emptiness.

MYRA’S LONELINESS

Loneliness is basically ’emotional emptiness’. In fact, Myra’s entire family are alone in this village. We don’t know where they are from, but Alice Munro gives us just enough information for us to deduce the parents are immigrants, the children first generation Canadian.

(Sayla as a first name is Arabic/Muslim. It is given to girls and means “Sunshine”. I wonder if Munro intended to keep Myra’s ethnicity ambiguous, as McCarthy did for Anton Chigurgh in No Country For Old Men.)

We can tell from the details offered — which people, which settings — are Othered. When the narrator describes Myra and her brother, she describes all the ways in which these children are not like white children.

Perhaps she expected me to run past and throw an empty Cracker Jack box in her face.

“The Day of the Butterfly”

LEAF HOUSES AND SNOW FORTS

The children make leaf houses in the fall and snow forts in the winter. These structures are designed only for play, are not for real combat, and are designed to be destroyed by the environment. The walls of leaves contain no rooms inside them; the fort protects no one from any real war.

PARROTING AND PLATITUDES

platitude:

- (countable) An often-quoted saying that is supposed to be meaningful but has become unoriginal or hackneyed through overuse; a cliché.

- (countable) A claim that is trivially true, to the point of being uninteresting.

- (uncountable) Unoriginality; triteness.

- (uncountable) Flatness; lack of change, activity, or deviation.

Then there’s the anodyne response of the Queen Bee classmate who has already learned that to be accepted as a lady in this social milieu, you must say the right things to the right people. What you really feel is irrelevant. This girl starts a fatuous game of imitating their young teacher in what seems a vacantly silly game, but which serves to rearrange the hierarchy. The one area an inexperienced teacher cannot control the class is the playground dynamics.

When these little women parrot their teacher, this foreshadows the platitudinous show of gift-giving at the hospital.

Later, when Miss Darling requires everyone to write a letter in hospital, all of the letters say the exact same thing. The children put up their hands to visit Myra in hospital because the alternative is supplementary reading. The mothers have made ‘imitation’ roses and lilies of the valley to tape onto Myra’s gifts.

MYRA’S PHYSICAL ABSENCE FROM SCHOOL

For a week, then two weeks, her desk was empty. Then we had a moving day at school and Myra’s books were taken out of her desk and put on a shelf in the closet. Miss Darling said, “We’ll find a seat when she comes back.” And she stopped calling Myra’s name when she took attendance.

“The Day of the Butterfly”

THE EMPTY CALORIES OF THE CRACKER JACK BOX

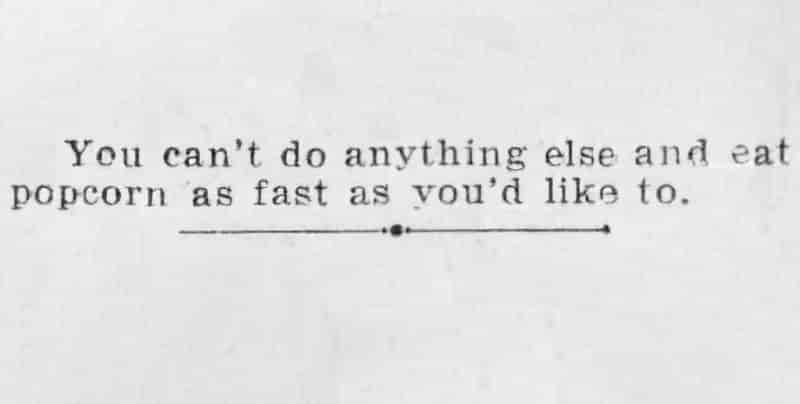

The phrase ’empty calories’ first appeared around the mid-1900s and continues to grow in frequency of use. The term refers to foods which are high in calories but low in nutritional value. Cracker Jacks, or any candied popcorn, are the epitome of empty calories. The popcorn itself is a nice metaphor for this story, starting out as something small and hard, then suddenly bursting into something consumable before disappearing again, hardly noticed as someone eats it mindlessly, probably not at the table and mindfully—probably while doing something else. The life of a Cracker Jack, then, is how we might describe the flurry of attention extended to Myra on her deathbed.

THE LEATHERETTE CASE WITH A MIRROR IN IT

Like the gilt and rose teapot of “The Office” included in this same collection of stories, the gift of a leatherette case is another multivalent symbol:

- The case is made of leatherette, not real leather. It is synthetic and therefore fake.

- It is an empty container, continuing the motif of emptiness.

- The case contains a mirror, and will be left with Helen for a long time, giving her ample opportunity to ‘reflect’ on her own role in Myra’s loneliness at school.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by writer and historian Dr. Lydia Pyne to talk about her new book, “Genuine Fakes: How Phony Things Teach Us About Real Stuff.” Lydia describes the fuzzy line between what’s real and what’s fake, sharing stories about nature documentaries, art forgeries, fossil hoaxes, lab-grown diamonds, and everything in between.

Genuine Fakes w/ Lydia Pyne

SYMBOLISM OF THE BUTTERFLY

Butterflies mean all sorts of things across time and culture—mainly to do with regeneration, transformation, ephemeral beauty and the human soul flitting between worlds, perhaps taking some kind of message or secret to the gods.

Looking at various butterfly superstitions around the world, the Irish idea of butterflies as the souls of children seems to line up with this story, in which a child is about to die. The ephemerality of life, the shortness of a child’s life and the brevity of a butterfly’s life all come into play here.

But I think, more significant, is the fact that this butterfly is fake and made of tin, alongside the reality that (real) butterflies sit with their wings together, whereas the blue tin version which came out of the Cracker Jack box would almost certainly have been presented with its wings splayed out.

And because a tin butterfly is not in flight, it is presented to the consumer as if pinned. (If you ever see a wild butterfly perched with its wings splayed out, it’s a moth.) Also, those Cracker Jack toys are designed for collecting. That is their only purpose. The shapes themselves are empty of meaning and utility.

In Alice Munro’s “Day of the Butterfly”, Myra is the pinned butterfly, or the collectible tin Cracker Jack toy. She exists to be ‘collected’ in the sense that the local, well-to-do families are buying the terminally ill girl presents as a way of amassing their own good deeds for some kind of karmic purpose. What Myra actually wants herself doesn’t come into it. Presumably no one asked Myra if she’d like to celebrate her birthday early. Chances are she knew exactly why an early celebration was happening. The early birthday would serve only as a stark reminder that her time on earth was limited. Only Helen, the narrator, seemed to intuit there was something wrong with forcing an early celebration on a sick girl.

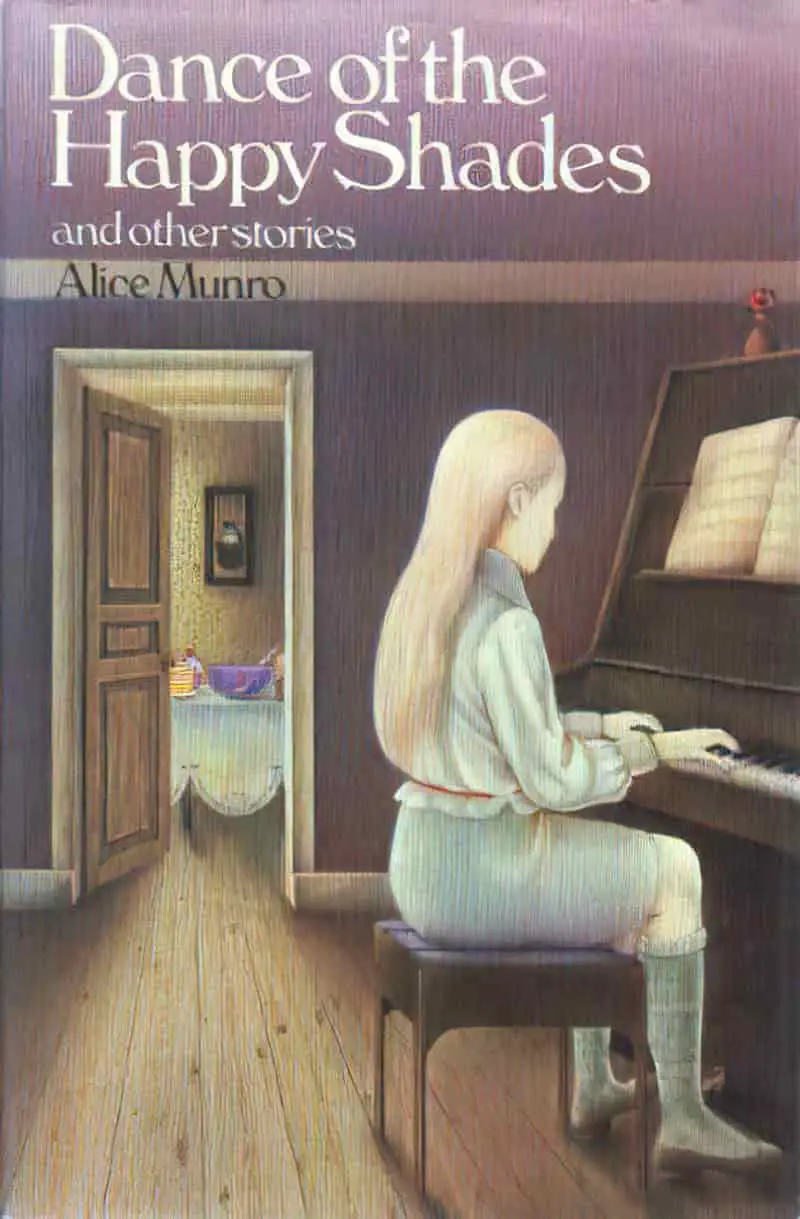

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly“

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.