**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

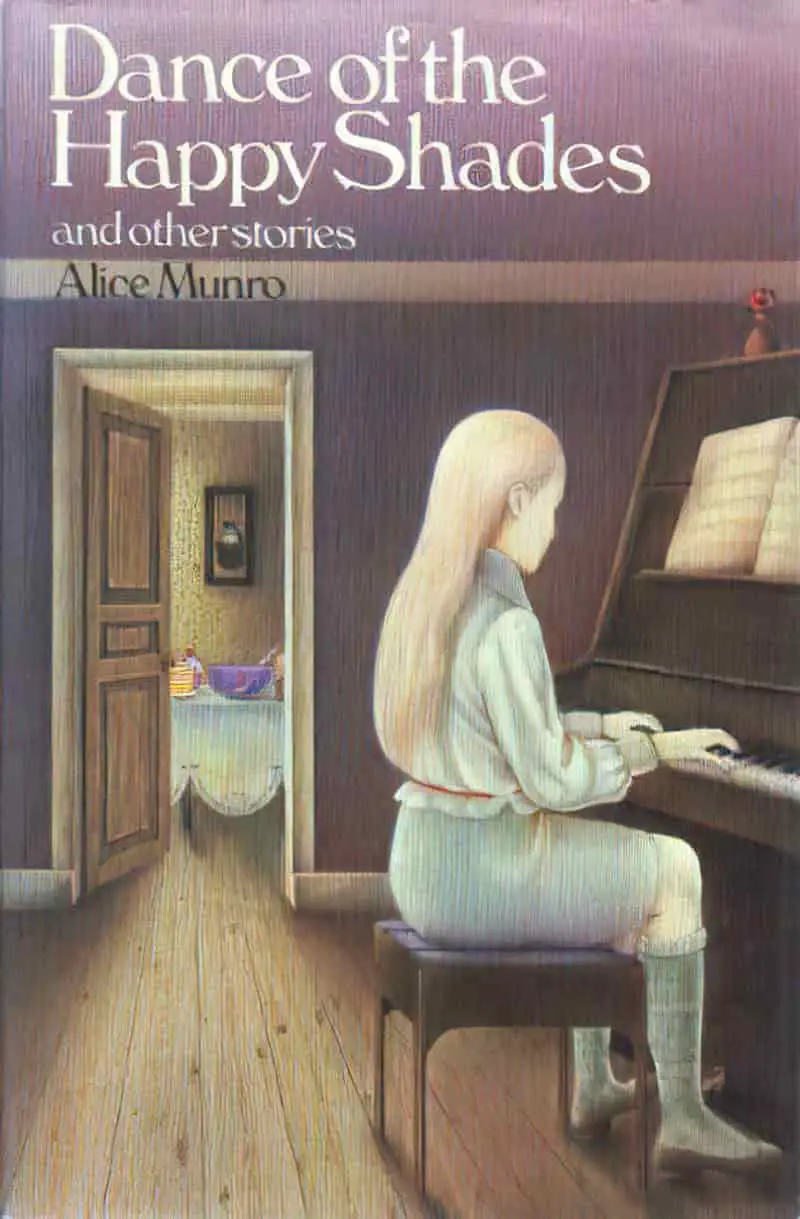

“The Time of Death” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro, included in the 1968 collection Dance of the Happy Shades. This story is about compassion, what it looks like on the surface, how performativity can erode genuine empathy, and about the unrealistic adult responsibility we give to girls.

Although Alice Munro is seldom called a feminist writer, many of her stories are about specifically female issues, this one included. The idea that girls are ‘little mothers’ is rife in our culture, and can be seen in contemporary storytelling. See: The Female Maturity Formula of Modern Storytelling.

This culturally shared narrative affects who we allow a full childhood, whose childhood is abscised, who we blame when things go wrong, and who we expect to provide care.

Like “Day of the Butterfly“, this story from the same Dance of the Happy Shades collection features a community coming together around death, doing all the expected tasks. But the family experiencing the grief was never really considered part of the community. These tasks feel, to this reader, performative and hollow. “Day of the Butterfly” featured characters in their childhood. This social phenomenon is the same, but concerns adults. Together the stories form a diptych which suggests the performative nature of community spirit starts in childhood and never abates.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE TIME OF DEATH” BY ALICE MUNRO

THE DIRT(Y) POOR

Leona Parry, mother of four, with unhygienic bathing practices, loses her eighteen-month-old son to a terrible domestic accident when she entrusts him to her nine-year-old daughter. At the time, Leona is sewing a costume for the daughter (Patricia) at neighbouring Allie McGee’s house, roughly using Allie’s sewing machine to knock up a cowgirl outfit for her daughter Patricia’s performance with the Maitland Valley Entertainers, who play all over the country at concerts and dances.

THE HORRIBLE ACCIDENT

Munro keeps this information from readers until we’ve met the main characters.

With her mother and father both out of the house, nine-year-old Patricia is in charge of her three younger siblings. decides to clean the house. She’s seen Allie McGee’s house and she wants a clean house like that. So she boils a large pot of water on the stove. Mercifully left off the page: Roping her younger siblings in to help. A full pot of boiling water spills onto the youngest boy who subsequently dies from his burns.

This particular accident used to be far more common, when children were charged with household tasks they weren’t yet strong enough to manage:

While deaths of children from disease may have been influenced by social factors, accidental deaths certainly were. Coroners’ records show that among slightly older children the accidental deaths of girls were most often the result of burns and scalds (in the home), while boys were most likely to drown (outside the home).

Women in England 1500-1760: A Social History by Anne Laurence

APPORTIONING BLAME

Here’s the other part of the horror: Leona Parry blames her nine-year-old for causing the death of her toddler son. In the depths of grief, she demands her nine-year-old daughter be kept out of her sight.

THE MANY IRONIES

“The Time Of Death” contains many small ironies which lead to a big one: A little girl is expected to mother, but she can’t. She’s still a little girl who needs mothering herself. As you read, look for various ironies and juxtaposition.

Alice Munro is giving us several tales in “The Time of Death”, and each thread juxtaposes against another:

- A community of adult women rally around and do the ‘right’ thing for a grieving mother in their community, but have difficulty dealing with Leona, who is a highly flawed individual. These women do not genuinely care.

- The story of a nine-year-old girl who is not doing ‘the right things’ around grieving, but who we eventually learn does care. Deeply. The nine-year-old cannot leave her live and return to a nice, clean house when the work of making casseroles and time of crying ends.

DESCRIPTION OF SETTING AT THE END

Typically, stories open with a description of the setting but Alice Munro inverts this practice and closes with a paragraph describing the village — a street of downtrodden houses which exist to support the local industry of the mill. Behind this street, Munro describes desolate farmland heading into winter. Readers are left with an emotion as much as a description of a community. We can use this emotion to hook into Patricia’s state of mind. We can also take a stab at her future outlook: Sure as the cycle of seasons, Patricia’s life will mirror the life of her mother.

“THE RED SHOES” BY HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN AS IMPLICIT ALLUSION

ALICE MUNRO AS QUIETLY FEMINIST WRITER

I believe there are similarities between Alice Munro and Angela Carter who, unlike Munro, is famed as a feminist subverter of old, misogynistic tales. Angela Carter wrote her re-visioned fairy tales after translating Grimm Fairy Tales. She got to the point where she had to do a mental mouthwash. I know exactly how Carter would have felt because, a few years ago, I made the decision to read every single one of the Grimm fairy tales back to back. After that dispiriting foray into deep misogyny I was left with a strong craving for Angela Carter’s cathartic retellings. Alice Munro doesn’t give you the catharsis, though. And that is probably why she’s not called ‘feminist’. Alice Munro writes realism, not supernatural fantasy, and you don’t get happy endings. You get nuance.

Before (re-)reading Munro’s “The Time of Death”, I recommend a quick skim of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Red Shoes“, published in the middle of the 1800s. (Or my analysis of “The Red Shoes” here.)

Young Patricia Parry of Alice Munro’s story is the clear great-great daughter of Andersen’s much maligned Karen, who — spoiler alert/content note — gets her feet chopped off by the executioner because she fell in love with a pair of red shoes. Both stories contain a horror, but only Andersen saw fit to describe the horror on the page.

Both stories open with a death in a poor family, believed to be caused by the young female main character. And because of a psychological phenomenon we now call avoidance, the girl doesn’t show the requisite amount of grief. Everyone assumes there’s something terribly wrong her, and she is punished heavily for it.

Andersen’s ‘the old lady’ is Alice Munro’s Allie McGee, Patricia’s large-bodied ‘benefactor’, who is really no such thing.

Like Karen, Patricia has dreams ‘above her station’ for a lowly poor girl. Everyone hates a girl who thinks too highly of herself.

I think I’m just as good as lots of those people who are sitting so smugly in church.

“The Red Shoes”

Munro’s Patricia has been cast onto the stage due to a big loud voice parsed as precocious singing talent. Her only way out of this poor life is to become a famous singer. Likewise, Andersen’s Karen sees a beautiful princess and wants to be like her. Karen literally wants to become a princess. How does she plan to do that? By acquiring an identical pair of red shoes. (How else?)

Karen and Patricia both end up at a shoe store (well, in Andersen’s day it was the shoemaker’s) where they acquire ostentatious shoes. Note that the wealthy benefactor in Andersen’s tale is literally blind. What about Allie McGee? What’s her ‘blind’ spot?

Eventually, Karen was old enough to be confirmed. She got new clothes and was supposed to get new shoes. The rich shoemaker who lived in town measured her little foot; his shop was in his house where large glass cases were filled with pretty shoes and shiny boots. It looked very nice, but the old woman could not see very well, so she got no pleasure from it. Among the shoes was a red pair, just like the ones the princess had worn. They were exquisite! And sure enough, the shoemaker said that he had sewn them for a nobleman’s daughter, but they hadn’t fit.

“The Red Shoes”

Allie McGee’s blind spot: She doesn’t understand Patricia’s psychology at all, holding the little girl at arm’s length, failing to afford her the grace of being a child, and therefore not yet in touch with her own emotions.

In Andersen’s story the old woman benefactor dies as the mother did, and the little girl loses yet another woman in her life. Again, Andersen suggests Karen as responsible due to proximity and apparent lack of care. She’s too darn enamoured by those devil shoes. She should have been taking care of the sick adult women in her life who have ostensibly been taking care of her. (Andersen makes no distinction between material and emotional caregiving.)

But whereas “The Red Shoes” is a disturbing and misogynistic tale, Alice Munro’s 1960s story asks us to reapportion blame. In fact, there’s no ‘blame’ to be had in “The Time of Death”. The environment — a Canadian working class mill town — has shaped these characters, made them who they are. There’s a morbid fatalism to this story, which reminds me of Annie Proulx’s grimmest tales. The events of “The Time of Death” are ‘an accident waiting to happen’. And we can extrapolate what Patricia’s life will look like after the story closes. Both Karen and Patricia will live lives in the servant class. Both girls have been brought down a peg. (Karen literally has two peg legs.)

Andersen’s frenzied dancing scene is transmuted into a different kind of catharsis in Munro’s story, as Patricia’s repressed grief inevitably catches up with her.

Whereas Andersen makes use of archetypes, Alice Munro deals in a different kind of ‘sameness’. Munro lets readers know that all the female characters in this cast are the same woman, each placed in slightly different circumstances. We might call these “counterpoint characters”, or different permutations of the same person. (Katherine Mansfield uses the same technique in “At The Bay“. Perhaps by coincidence, Mansfield also uses child characters to illuminate and observe social dynamics between adults.)

In “The Time of Death”, Patricia Parry is Leona Parry is Allie McGee.

Whereas Andersen’s tale is overtly Christian, Munro’s story doesn’t show church in a great light. (cf. The Army women, of limited help in a crisis.) Munro simply leaves us with a Christian (but not just a Christian) sentiment, the very same which closes Andersen’s story: There but for the grace of God go I.

CHARACTERS

LEONA PARRY

The story opens with Leona grieving on the couch of her own living room, surrounded by other women from the community.

Leona drew up her knees under the quilt and rocked herself back and forth as she wept, and threw her head down and then back (showing, as some of them noticed with a feeling of shame, the dirty lines on her neck).

“The Time of Death” by Alice Munro

We later learn (from the ‘village voice’ narrator) that Leona is ‘unwashed, unliked and desolate’.

In the dark overheated kitchen the women felt the dignity of this sorrow in their maternal flesh, they were humble before this unwashed, unliked and desolate Leona.

“The Time of Death” by Alice Munro

THE COMMUNITY WOMEN

The word ‘masks’ is doing a lot of work here. A mask suggests a mindful expression which isn’t entirely genuine.

And the women in the kitchen would crowd around the couch, their big bodies indistinct in the half-light, their faces looming pale and heavy, hung with the ritual masks of mourning and compassion.

“The Time of Death” by Alice Munro

ALLIE MCGEE

ALLIE MCGEE AS CHORIC FIGURE

Allie McGee has a front-row seat to the Parry tragedy because Leona Parry was at Allie’s house using the sewing machine when she left her children alone. We can deduce from this that Allie knows Leona very well.

Allie McGee cried. She was stout, placid-faced, big-breasted; she had no children.

“The Time of Death”

For the first part of the story, neighbour Allie McGee functions as a viewpoint character, or more like the ‘choric figure’ of a tragedy. (Note that Andersen also does his own version of an empathy switcheroo.)

As the reader listens to Leona Parry speak about the tragic incident, the character of Allie McGee is there to remind the reader that we are hearing an unreliable narrator. (Another irony: It is kept as a reveal to readers that Allie McGee is herself unreliable. She’s nowhere near as compassionate towards the Parrys and their children as she thinks she is.)

WHY ALLIE MAKES A GOOD VIEWPOINT CHARACTER

Allie is different from the Community Women because she doesn’t have young children of her own and she is married to a store man, not a mill worker. But she is of the same social class as the Parry family, which Munro shows succinctly via non-standard grammar: “You should of seen the bedsheets I had them on.”

The Parry children know Allie as “Mrs McGee”. Patricia is sufficiently acquainted with Allie to know that Allie scrubs her floor using hot water. Readers have it confirmed: Allie McGee has taken a fairly active role in the care of Leona’s children over the years. It’s significant that Allie has no children of her own (at least none who are young and still at home). This frees her up somewhat to help care for neighbourhood children.

Here’s another irony: Allie understands the reality of Leona Parry’s children precisely because she isn’t filled up with mothering duties herself. I call this an irony because we live in a culture which vilifies and mistrusts childless adults, frequently viewed with suspicion, assuming childfree adults know nothing about how to care for anyone other than themselves. (This idea was even more prolific in the mid 20th century.) In contrast, Leona has more children than she can cope with, yet an abundance of babies hasn’t helped her get better at caring.

ALLIE MCGEE AS FALSE JUXTAPOSITION TO LEONA PARRY: DIFFERENT IN APPEARANCE ONLY

The details the children notice when they stay the night at Mrs McGee’s are telling. They notice the beautifully made-up beds, the clean smell. They notice these details precisely because their own house is nothing like this. In Patricia’s desire for her own house to look (and smell) as homely as Allie’s, her little brother was killed. (Like Andersen’s Karen, Patricia wanted to have nice things, and this desire has led to death.)

At a deep subconscious level, her own part in this terrible chain of events surely isn’t lost on Allie McGee herself, who might be wrestling with her own peripheral role. (If Allie didn’t have a clean floor, young Patricia may not have thought to wash the floor using scalding water like Mrs McGee.) In refusing to meet Patricia where she is in her grief, we see Allie McGee pull away emotionally. Perhaps as a self-defence mechanism.

REVEAL: ALLIE MCGEE IS NO MORE CARING THAN THE REST OF THE COMMUNITY

At the end of the story, The Neighbours are pleased to overhear little Patricia finally realising her grief, in a very vocal way. This pleasure does not focus on little Patricia finally realising her grief. No.

No real care extends to this little girl. The caterwaul simply means the neighbours can go on despising the Parry family as they did before. Note that Munro says ‘dislike Leona‘, not ‘dislike Patricia‘. However, it is clear from all that came before, Patricia is considered a mini-Leona. She will be treated the same as the dirty, despicable, negligent Leona, and the neighbours understand what the reader has already worked out: That little Patricia will never make it out of the village as a famous movie star or singer. She’s starting to lose her youthful cuteness, the only thing she had going for her. Due to neglect, her teeth are already starting to rot.

LITTLE PATRICIA REPRESENTS A MINI WOMAN WITH SIMILARITIES TO ALLIE AS WELL AS LEONA

We are not told directly that Allie McGee is one of those Pleased Neighbours who can go on disliking the Parrys, but we now have enough information to include her in this uncaring group. Allie doesn’t identify with Patricia at all. During a switch to Patricia’s point of view, Patricia overheard Mrs McGee talking to the shoe salesman, expressing a creeped-out dismay that Patricia wasn’t displaying grief in a correct and timely fashion. Mrs McGee doesn’t have the emotional literacy to understand why young Patricia might be distancing herself from the tragedy. (Irony: This is exactly what Allie McGee is doing herself. The only difference is in their performance.)

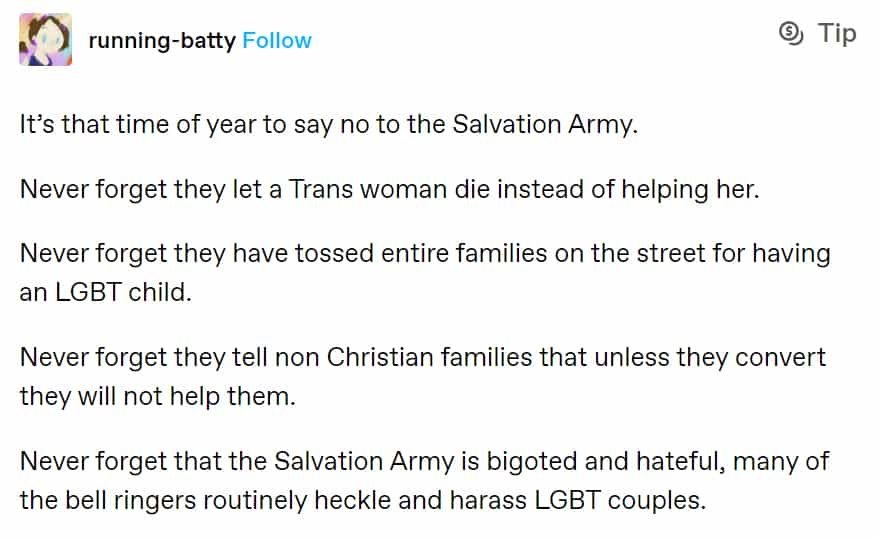

THE SALVATION ARMY WOMEN

The assembled community women ‘listen uneasily’ as the Salvation Army women speak:

THE YOUNGER SALVATION ARMY WOMAN

And the girl from the Salvation Army would say, in her gentle unchanging voice, you must forgive her, Mrs Parry, she is only a child. Sometimes the Salvation Army girl would say: It is God’s will, we do not understand.

“The Time of Death”

I mean, she’s being half helpful?

THE OLDER SALVATION ARMY WOMAN

The other woman from the Salvation Army, who was older, with an oily, sallow face and an almost masculine voice, said: In the garden of heaven the children bloom like flowers. God needed another flower and he took your child. Sister, you should thank him and be glad.

“The Time of Death”

Many of the women cried, but not the two from Army.

“The Time of Death”

Note that Munro eventually eventually shortens ‘Salvation Army’ to ‘Army’, highlighting the forceful, intrusive nature of these women.

Psychologists tell us that humans have a hard time sitting with ambiguity and that we will often go to great lengths to avoid it.

In the late 1960s, Swiss psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published a book about the process of grieving for one’s own life when death approaches. (You’ve probably heard of the five stages of grief. The theory is regularly misapplied to other types of grief these days. Another common misinterpretation: that the stages happen in a prescribed order.)

Healing Your Heart at the Hidden Brain podcast

I took away one standout detail from reading Kübler-Ross’s On Death & Dying. There are two categories of people who deal best with their own impending death: The very religious and the very atheist. It’s everyone in between who has a tough time of impending death.

The Salvation Army women likely do derive great comfort from turning to God. But with the wrong audience, these words of ‘comfort’ are — another irony — highly discomfiting. The Salvation Army women misread the audience before them, riding roughshod over their needs. They mean to use the opportunity of a child death’s as a conversion opportunity. Everyone in this story is riding roughshod.

There’s another reason why The Community Women listen ‘uneasily’ to the Salvation Army women. These Army women are slightly exaggerated versions of themselves. Their sudden presences, followed by sudden departure, is not about supporting a grieving family. They have their own agenda. The Community Women: Rallying round a grieving family supports their own view of themselves and their community as caring and feminine. It is gender affirming to provide casseroles and to cry.

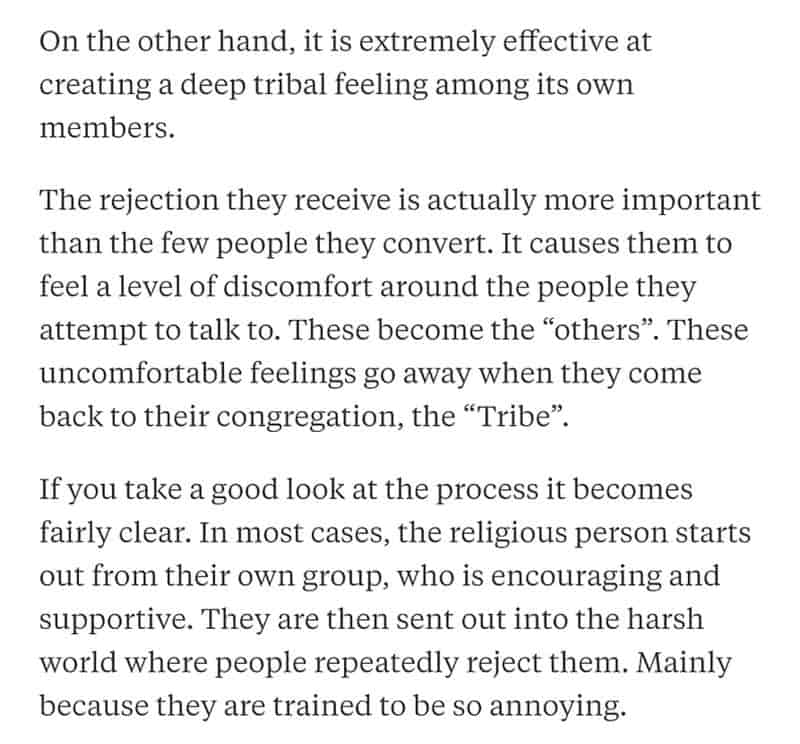

For he Army women: conversion. However, even religious conversion efforts are never really about converting or helping others. Evangelical efforts serve existing members of a church:

There is a form of charity where it really doesn’t matter what your intentions are. Give money. No good cause is harmed by it. Give money for your own selfish reasons entirely. Still, no one is harmed by it.

SUPERHEROING

I’ve been watching a particular person in the last while. He has a superhero complex, and I kind of want to explain what that is.

So when you’re doing work – be it voluntary or paid – that has to do with vulnerable people in shit circumstances, there’s this human trait which comes out which is really dangerous. I call it super-heroing.

Basically we all have this need to be seen, and heard, and valued. So far, so human. But we also need to be needed.

When we are around people who are really vulnerable, we get all adrenalised and go into crisis mode – FIX IT mode – and this, my friends is very very dangerous.

Someone’s in a really dangerous situation and you’re going to swoop in there and save them, right? WRONG. Because swooping in very rarely works, and as for saving people, well there are better ways of doing that if someone’s life is at risk.

When you do first aid, they always tell you if there are live wires in the water and you want to get to the person who’s at risk of being electrocuted, there’s no point wading in there, cos you’ll die and then what use are you?

And don’t do it if their life ISN’T at risk. Because the swooping, and saving, and super hero stuff? That’s about US, and not THEM. That’s feeding our own needs, and not theirs.

We aren’t useful as a resource unless we understand and acknowledge very clearly that THEY are the hero of their own stories. Not us. Never us. I used to do this. And then I stopped. Because I came to understand that I’m not a superhero.

I’m just me. And I do as much as I can, when I can. How did I stop? I made sure I checked that the people I was walking alongside felt safe to tell me if I was getting too ahead of myself. I checked in with MYSELF to see who I was doing things for.

I see other people doing work kind of like me – running charities that are helpy sort of thing and I cringe because what I see is a lot of well intentioned people with saviour complexes.

They’ll crash and burn because there will never be enough gratitude or praise in the world to make their heroism worthwhile. Don’t be a hero. That’s harmful to you and everyone around you. Just be a resource. It’s a lot healthier. Peace out.

@aunties_the 5:16 PM · Jul 8, 2021

PATRICIA PARRY (“THE LITTLE SWEETHEART OF MAITLAND VALLEY”)

Patricia Parry is Leona’s nine-year-old daughter, and was left in charge of her younger brother when he died.

Other stage names:

- Baby Blonde

- Pint-Size Kiddie with the Great Big Voice

Because of Patricia Parry’s naturally blonde hair, which doesn’t darken (a highly prized attribute in those days), her mother entered her in pageants assuming her precocious. (Requiring precocity.) Ironically she is a frail child. The stage names each contain an irony. ‘Blonde’ most commonly describes a sexually mature young woman, but here the subject is a nine-year-old. ‘Pint-Size and ‘Big Voice’ illuminate another ironic juxtaposition.

These small ironies lead into the big one, which leads to the tragedy.

Patricia’s so-called precocity is an illusion on Leona’s part — one of many. Patricia is a nine-year-old child. However adept she appears on stage, and should never have been entrusted with the care of a younger child. A nine-year-old girl is not a miniature mother. Munro’s story illuminates the reality that girls are often expected to grow up prematurely, especially when they are the eldest siblings in their family (and even more so when they are little Black girls, though race isn’t the issue in this particular story).

Patricia knows Benny is ‘stupid’ but doesn’t hold this against him. She uses movie magazines as an escape from the drudgery of the mothering duties she never asked for. Her dialogue is how we imagine Leona Parry speaks to her children. Patricia has perfectly absorbed her mother’s diction and the permanently annoyed tone of an overwhelmed, domineering parent.

BENNY PARRY: THE PERFECT DEAD SON

A mother who expects her nine-year-old daughter to take on the responsibilities of a mother is of course far more forgiving of a son. The same internalised misogyny which led to one view also led to the other.

I nursed him until he was ten months old. He was so good, too, you never would of known you had him in the house. I always said, that’s the best on I ever had.

“The Time of Death”

When Leona tells the women she nursed Benny until he was ten months old, this suggests her daughter, Patricia, didn’t receive the same care, forced off the breast (literally and metaphorically) at a much younger age. Unlike Patricia, whose name is not shortened to Patty, the son is eighteen months old, still young enough to attract the diminutive name of ‘Benny’.

Unreliable narration alert: Was this boy really the best of her children, or was this simply her view, in light of his gender privilege? The reader is encouraged to question everything Leona says.

The village voice, perhaps through the mind of (an older) Patricia, who clearly looks after him enough to know what her youngest sibling is like:

Other little kids only thirteen, fourteen months old knew more words than Benny, and could do more things, like waving bye-bye and clapping hands, and most of them were cuter to look at. Benny was long and thin and bony and his face was like his father’s–pale, mute, unexpectant; all it needed was a soiled peaked cap. But he was good; he would stand for hours just looking out a window saying Bow-wow, bow-wow, now in a low questioning tone, now crooningly, stroking his hands down the window-pane.

“The Time of Death”

This description suggests a developmental delay or neurodivergence (perhaps autism before autism had a name). Though I suspect it’s supposed to serve as evidence of poor, absent mothering.

MR PARRY

We don’t hear much about the Parry father, Leona’s husband. The men of this town are employed by the local mill, so we can assume Mr Parry is a millworker.

One paragraph establishes him as an emotionally immature man, who cannot comfort his wife and living children, and whose difficult emotions are all transmuted into anger, the only difficult emotion permitted for men. Via Patricia’s point of view we learn he barely speaks to his family in the home. The dead toddler is compared to the father, but the father could equally be compared to a toddler.

GEORGE AND IRENE PARRY

George and Irene are the other Parry children who nine-year-old Patricia was in charge of in her parents’ absence.

These children are far more visibly upset about their little brother being in hospital than Patricia appears to be, but that’s because they are allowed to grieve. As younger children, they haven’t been expected to parent.

Patricia has never been afforded the opportunity to be a weak child, even though she is quite weak in body, and so George and Irene’s older sister doesn’t let her mind entertain the possibility that Benny was badly burned. She does this by pretending to herself that she knows things when in reality she has no more information than another other child:

What’s the matter with you? Patricia said.

He cried awful, Irene said, her face in the pillow.

Well it hurt, that’s why he cried. When they got him to the hospital they gave him some stuff that made it stop hurting.

How do you know? George said.

I know.

“The Time of Death”

THE SCISSORS MAN

I’ve tried to find out if ‘scissors-man’ has meaning beyond this story, but from what I can gather, Old Brandon is the door-to-door salesman of knives and scissors who happened to sell the family the precious scissors the children use to make their paper dolls as they imagine a better life for themselves. Perhaps he fills the (benevolent) executioner’s role cf. “The Red Shoes”?

SCISSORS AS EMOTIONAL STUNTING

The Parry children previously identified with this man as he is as dishevelled as they are, in a stained brown overcoat, a hem hanging ragged, a crownless felt hat. But after the brother’s death, nine-year-old Patricia associates the activity of cutting clothes for paper dolls with what happened immediately after. Her grief comes on suddenly and loudly (cf. the main character of “Postcard“, in the same collection.)

Note that girls are not permitted to be loud, except when their loudness serves as a performance for the benefit of others. Alice Munro has used a literal performance in this story to illuminate the unpaid performance which is maternal femininity. Almost from birth, Patricia has been required to perform onstage. The community then wonders why she is so very good at masking her true feelings in service to others.

COMPASSION FATIGUE

Patricia’s full-time performance mirrors the trajectory experienced by women like Allie McGee, who are required to provide casseroles, tears and clean sheets in service of others, but who then, ultimately, have no more sh;ts to give. The performance of maternal femininity is exhausting. (This is called empathy burnout or compassion fatigue.)

The scissors symbolise a cutting-off of emotion, divorced from action. When surrounded by people in constant need of care, this is a necessary adaptation.

SCISSORS AS BIFURCATION: BEFORE AND AFTER TRAUMA

For Patricia, scissors will never be the same.

Scissors carry the symbolism of bifurcation, of a before and after. The death of their younger brother means life will never be the same. Hence the title. The time of death. Patricia is the main character. The death is her spiritual and emotional death.

But what about the mother? Leona Parry has lost a son but for her, nothing has changed. She had no epiphany. Leona is determined to go on as before. For this overwhelmed and slightly narcissistic parent, it may not be so hard to get past her blame of Patricia. Ironically, this is not because forgiveness and understanding is involved. Leona uses her oldest daughter in many ways, as babysitter, as performing monkey. So long as the daughter continues to have utility, Leona can go on as before. She was never emotionally connected to her daughter in the first place, so it was never a case of regaining anything back. There’s no warmth to get back. (Note also: Leona’s little boy died from scalding warmth. Symbolically, too much warmth can get you killed.)

(The key feature of narcissists: they are addicts. Their addiction is ‘narcissistic supply’. Leona is using daughter Patricia’s popularity on stage as narcissistic supply.)

THE DOG

A neighbour’s dog is mentioned several times before the third, harrowing scene: The howl a dog makes when it is injured, to describe the sound of the scalded toddler.

Leona seems to regard her children as farmers of yore might regard their working dogs: Utility first and foremost. Dogs come, dogs go. And so do Leona’s kids.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Shirley Jackson was a different kind of writer, but Jackson also produced a short story featuring a girl character somewhat like Patricia. Unlike Munro’s “The Time of Death”, Jackson’s tale is (probably) supernatural.

In “All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson, A Wednesday Addams archetype, fifteen-years-old, can see the future and knows when people are going to die, including her own parents. This short story is narrated by the busybody next door neighbour who finds the girl creepy, but does her duty anyway, caring for this kid until a distant relative arrives to relieve her of the burden. Like Patricia in this story, the girl expresses no outward remorse for her dead family and creeps out the well-meaning but ultimately unempathetic woman next door who believes she is going above and beyond for this girl.

Though “All She Said Is Yes” is supernatural, “The Time of Death” realistic, both stories deal in recognisable themes concerning the emotional labour we expect of women from a very young age, and how that expectation can turn into simplistic performativity which ultimately robs adult women of true compassion.

FURTHER READING

OTHER STORIES IN DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death“

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.