This famous tale is also known as The Princess And The Frog, The Frog Prince, A Frog For A Husband and similar variants. In most of these stories the princess is depicted as a spoilt brat.

Sometimes the story goes so far as being called The Kind Stepdaughter And The Frog, which is actually more like The Fairies (which stars a fairy rather than a frog and has jewels falling out of the young woman’s mouth) than it is like my versions of this frog fairytale from childhood.

Humans Marrying Animals

There’s an entire category of Märchen about humans who marry animals, or rather, a human being who has been (off-the-page) transmogrified into the form of an animal. I suppose these humans have been cursed by a witch, and I would very much like to know that particular backstory, but anyhow, “The Frog King” is the standout example of this folklore motif. This is a European story, but can be found all over the world. Mermaids, seals and swans are also popular as marriage partners in animal form.

Where the groom is an animal, the young woman doesn’t want to marry an animal. It never occurs to her that if everyone is forcing her to marry this talking animal, he might actually be a human underneath. These marriages are forced.

Where the bride is an animal, she’ll be the victim of trauma. Again, stories emphasise the trauma of the female partner. She’ll have been abducted, forced into an unhappy marriage, perhaps her husband hit her or broke some other societal taboo. Then she finds a means to escape (e.g. a magic cap/skin/feather cloak). There will be storyworld rules about what you are and aren’t allowed to do with this woman: You can’t look at them in a certain time/place, you can’t call their name, you can’t ask certain questions or she’ll vanish (e.g. “The Porpoise Girl”, a Micronesian tale, or in Irish tales about the Merrow/mermaid). The best known fairy tale about an animal bride is the “Swan Maiden”. This story has been traced back to Rig Veda (India).

Moral Lesson

There’s no shortage of fairytales which teach the lesson that girls must just marry who they’re told to marry. Even if they find the man repulsive, once she gets to know him she’ll suddenly wake up to herself and find him attractive. This may be an example of what Marina Warner has called the ‘death by engulfment’ fairytale. Unlike fairy tales starring boys and men, who fight big struggles to overcome their personal demons, the death by engulfment plot is about the psychosexual trauma of being a young woman forced into marriage and childbearing. A story such as The Frog Princess may have been created and retold by women rather than men, as a way of coping with being a reproductive vessel throughout the long history of humankind in which women had no say over their reproduction. Bluebeard is another example of a ‘death by engulfment’ tale. “Go with the flow and everything will be all right,” this story tells them.

The Frog Prince And Rape Culture

The discourse around rape culture that’s heightened over the past decade has turned a fairytale such as The Frog Princess into a very obvious rapey, creepy story and I find it amazing how seldom this particular tale is updated for a modern young audience, even as other tales are frequently riffed on.

The Frog Prince requires a certain view of morality that can be seen even in much more modern children’s literature:

Everything was beautiful and good except Laura. She had broken her promise to Pa. Breaking a promise was bad as telling a lie.

By the Banks of Plum Creek by Laura Ingalls Wilder

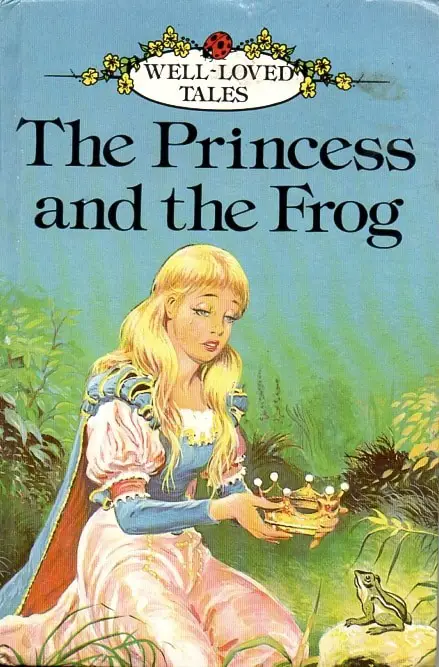

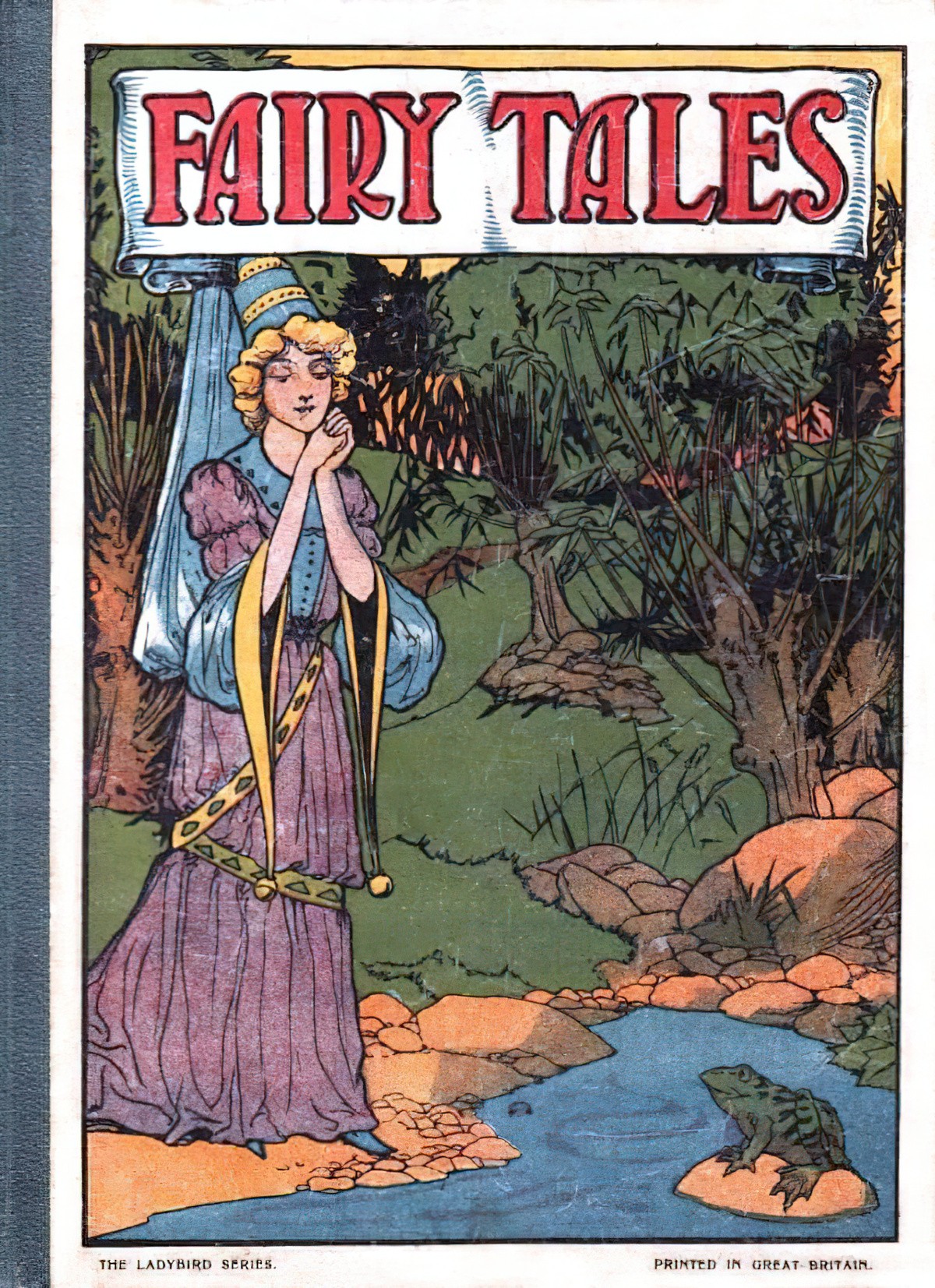

This view of lying and morality is heavily gendered. Overwhelmingly in traditional stories it is young female characters who are punished heavily for promising something, often under a degree of duress, then going back on ‘their word’. Note that in the Ladybird edition, the princess actually says:

“I’ll give you anything you wish for… You can have my clothes or my jewels or even my golden crown, if only you will find my golden crown.”

She promises anyTHING. She does not, at any stage, promise a frog herSELF.

When the frog specifies that he wants to marry her, she assumes (quite rightly, I would think) that he’s ‘talking a lot of nonsense’. After all, retrieving a ball, golden or not, from a shallow pond is hardly a favour that warrants sexual slavery for the rest of one’s life.

Apart from the frog’s complete manipulation of her intent, evident in transcripts of rape trials all around the world, there are other significant real-world problems with the moral lesson in this book:

- The young woman learns she has no right to change her mind about anything, even if she matures as a person. And main characters always change the course of a story; that’s what makes a story a story.

- In cases where the promise involves male disappointment, she learns that his right to receive is greater than her right to refuse.

- She absorbs the idea that a ‘yes’ in a previous situation also means an unspoken ‘yes’ in a subsequent situation.

- As long as the prince has ‘a kind face’ and she is sexually attracted to him, previous horrible acts of duress dissipate as if they never happened.

I have no time for the view that young readers get nothing out of such fairy tales, being too naïve to even understand the nature of sexual consent. I asked my six year old daughter, who enjoys this story, who was the ‘goodie’ and who was the ‘baddie’ in this story. At the time, she said “The princess should have kept her promise.”

“Should she have to marry the frog, even if she doesn’t want to?” I asked.

“Yes.”

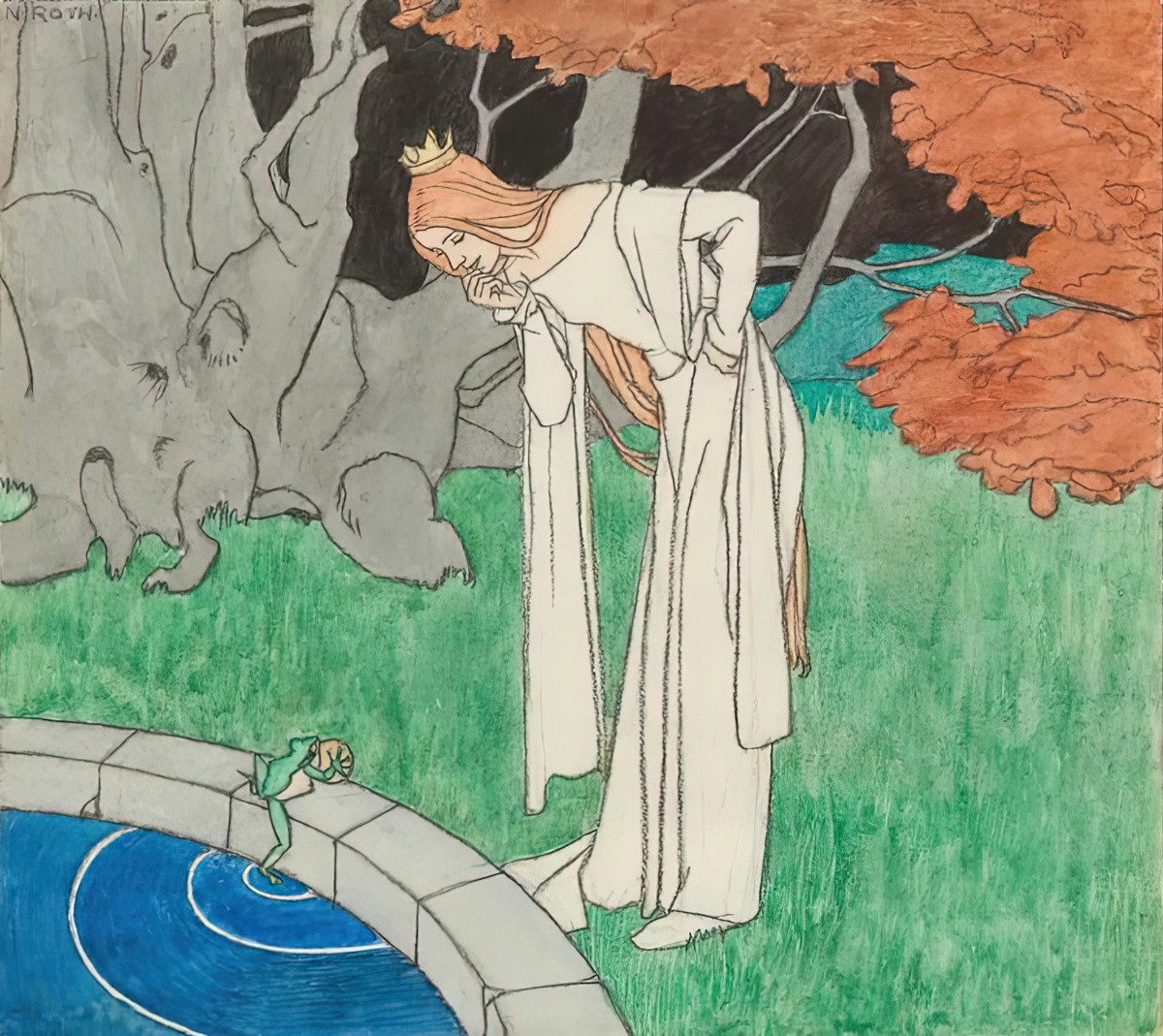

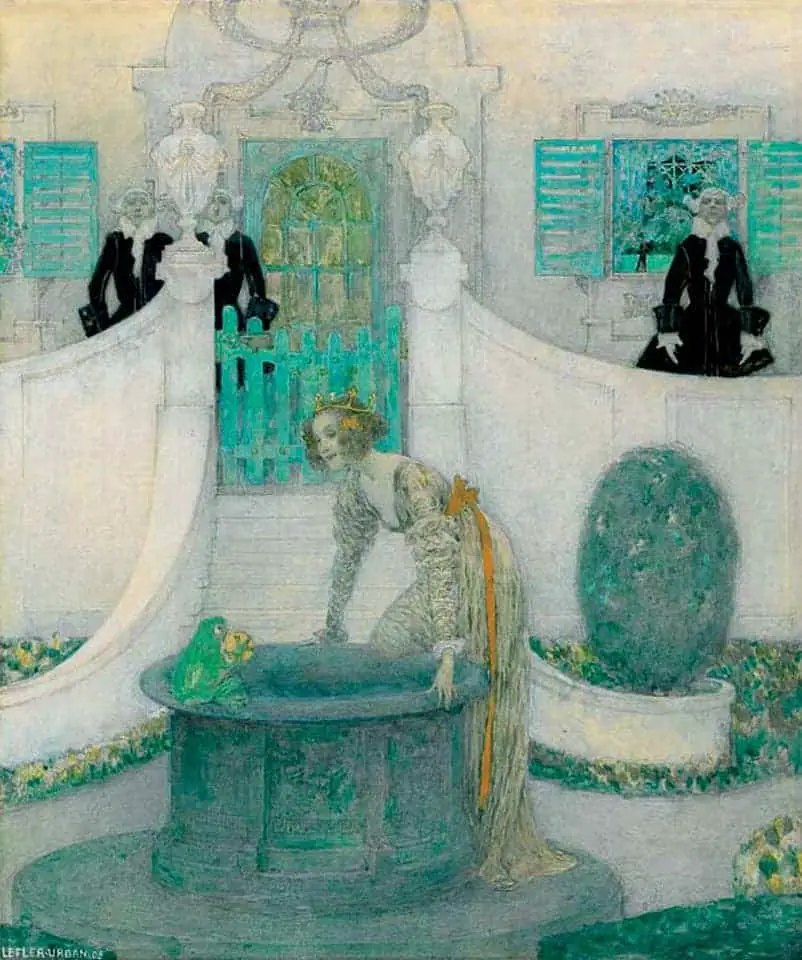

I highly recommend asking your children similar questions after reading this story to them. You might be surprised by what they’ve absorbed. It should come as no surprise; everything in the illustrations and text encourages empathy with the frog rather than with the too-beautiful-for-her-own-good princess.

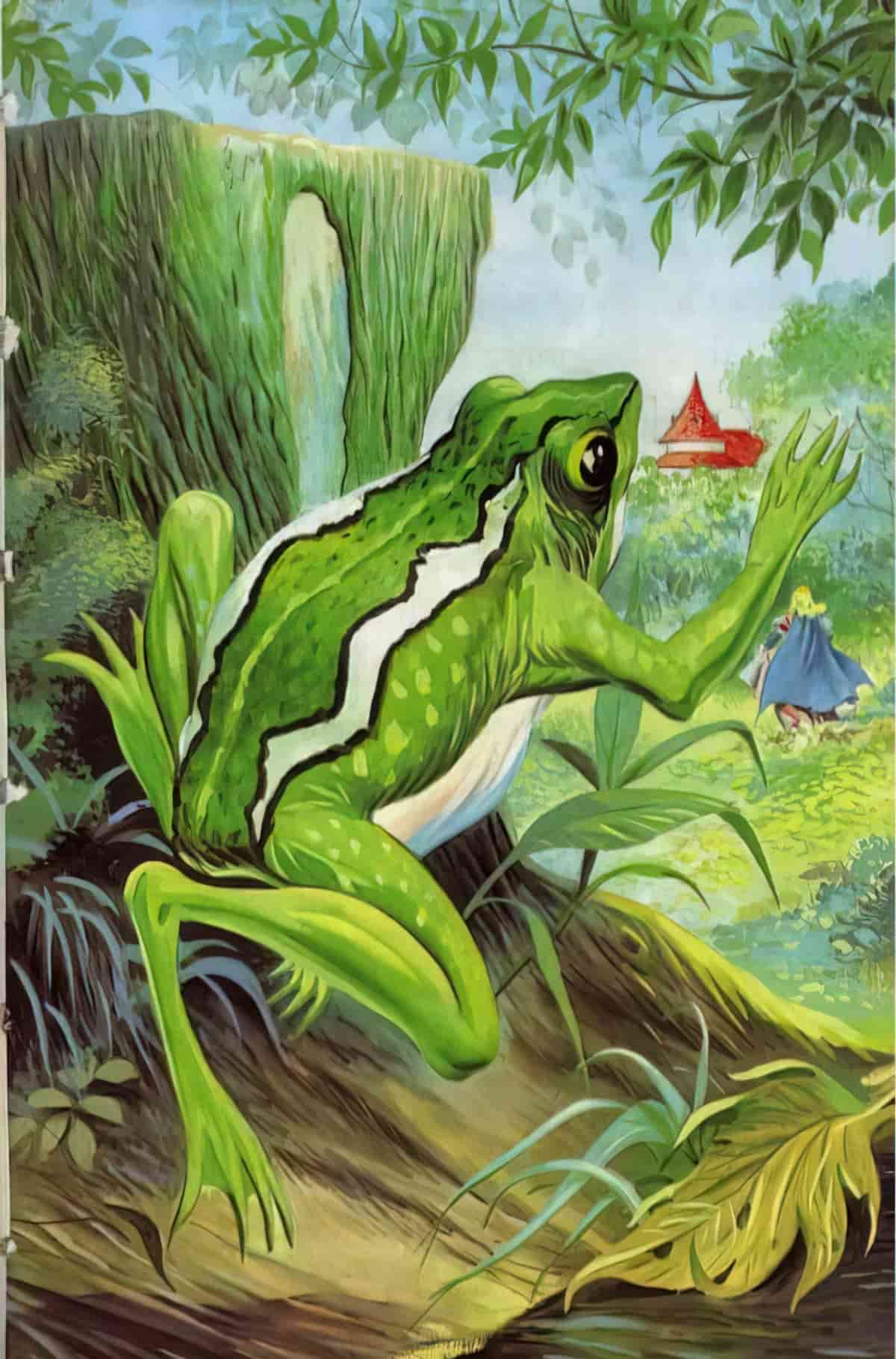

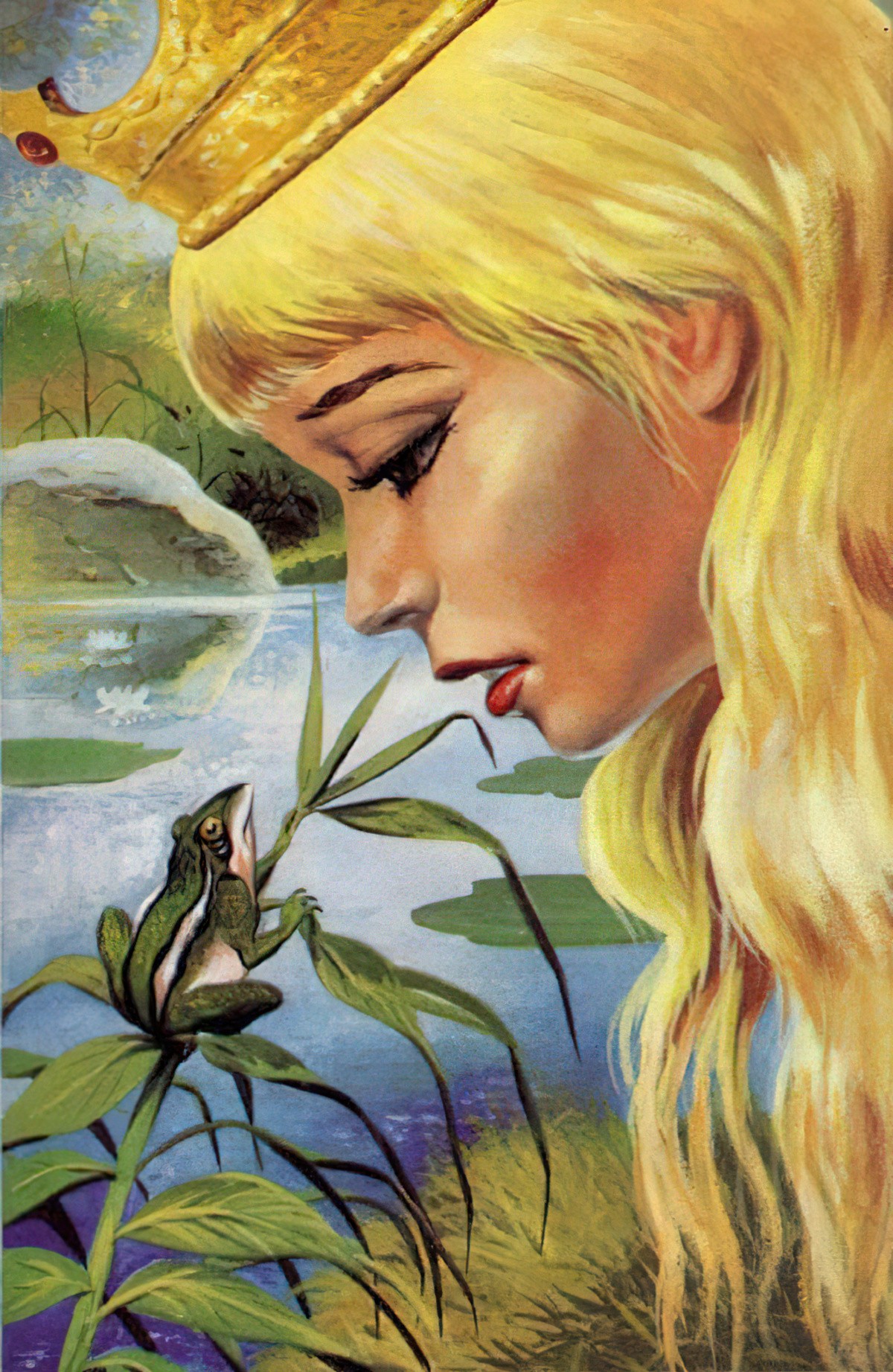

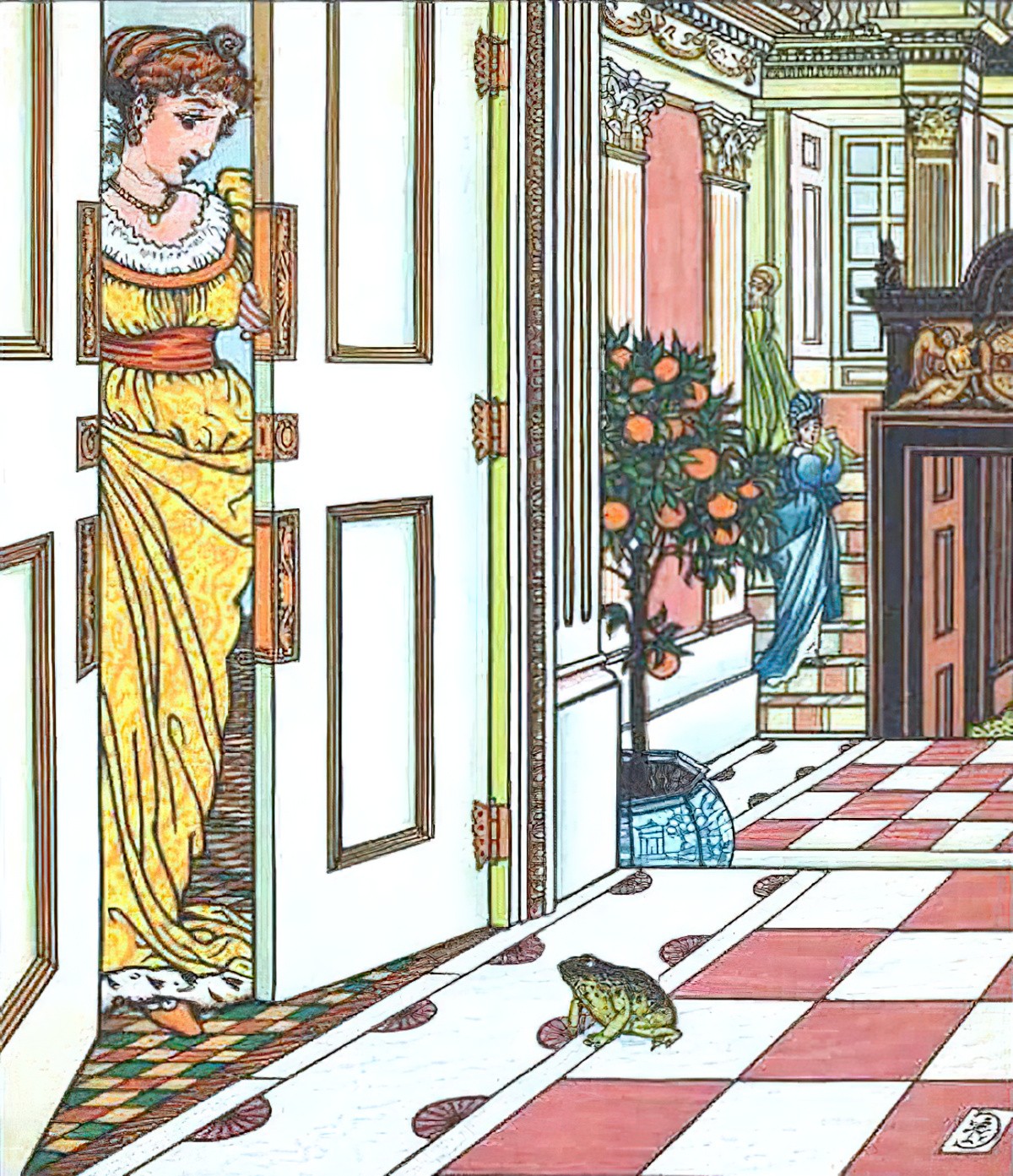

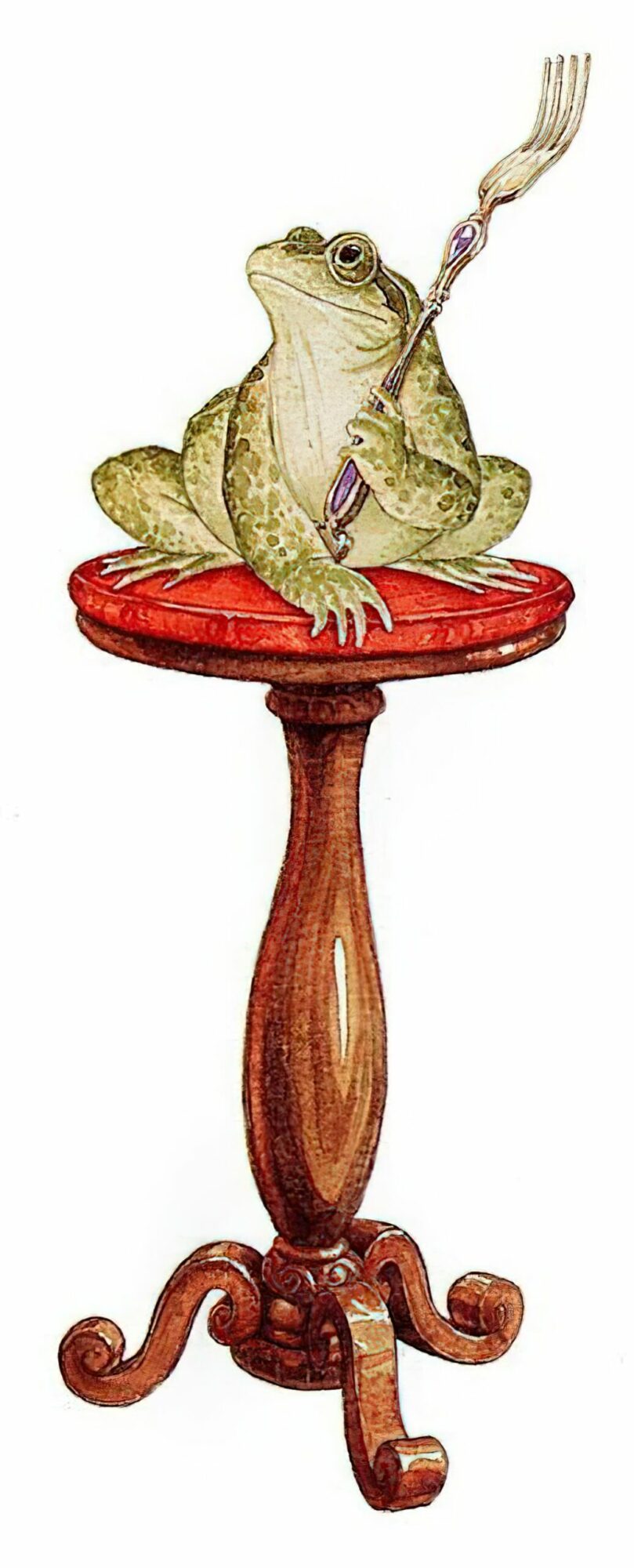

Take this image for instance. We have a frog alone, in the foreground. His hopes for happiness have just been dashed. Also, the young reader familiar with fairytales will know this is actually a prince.

“Wait for me! Wait for me!” croaked the poor frog. “I can’t run as fast as you can!”

This show of abject helplessness reminds me very much of an episode of The I.T. Crowd in which Roy elicits manipulative empathy by pretending to need a wheelchair.

The difference is, the comedy version makes fun of Roy; the fairytale frog elicits genuine empathy for the frog.

Story Structure of The Frog Princess

Whose story is this? Do I treat the princess as the main character, or the frog? The frog is the man with the plan. The princess is reactive. But that’s not how we can tell the main character of a story: Best to ask, “Who changes the most?” At first glance the frog changes the most — from frog to human. But this is not a psychological or moral change. Instead, it’s simply a change of circumstance, and those don’t count when we’re talking specifically about character arcs.

Indeed, the Princess undergoes the change of heart. The princess is the main character.

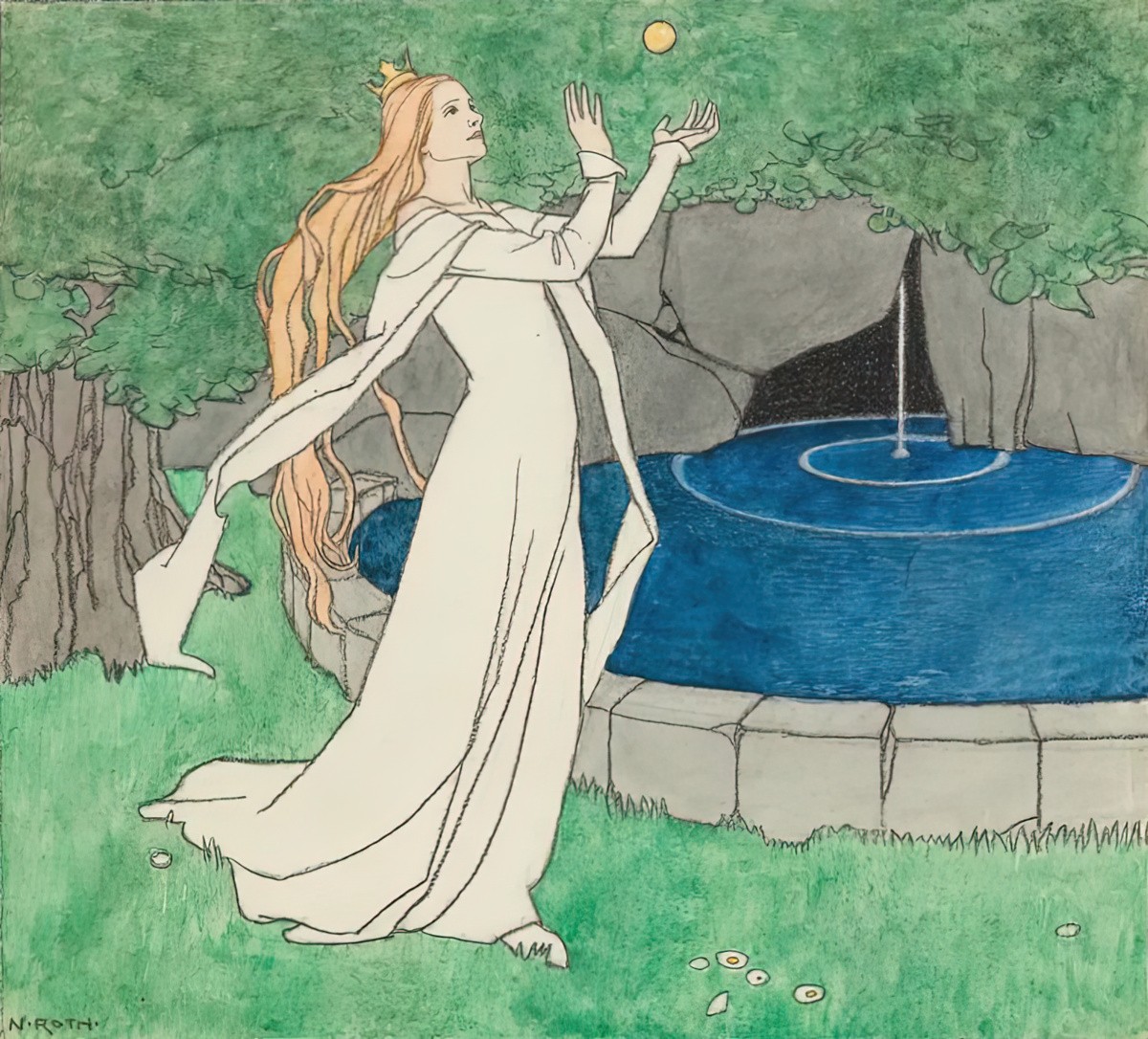

The Princess has been playing with a ball near a body of water (a well or a pond, typically) and the ball falls into it. She is unable to retrieve it herself.

See also: Symbolism of the Well.

The Golden Ball Scene In The Frog Princess

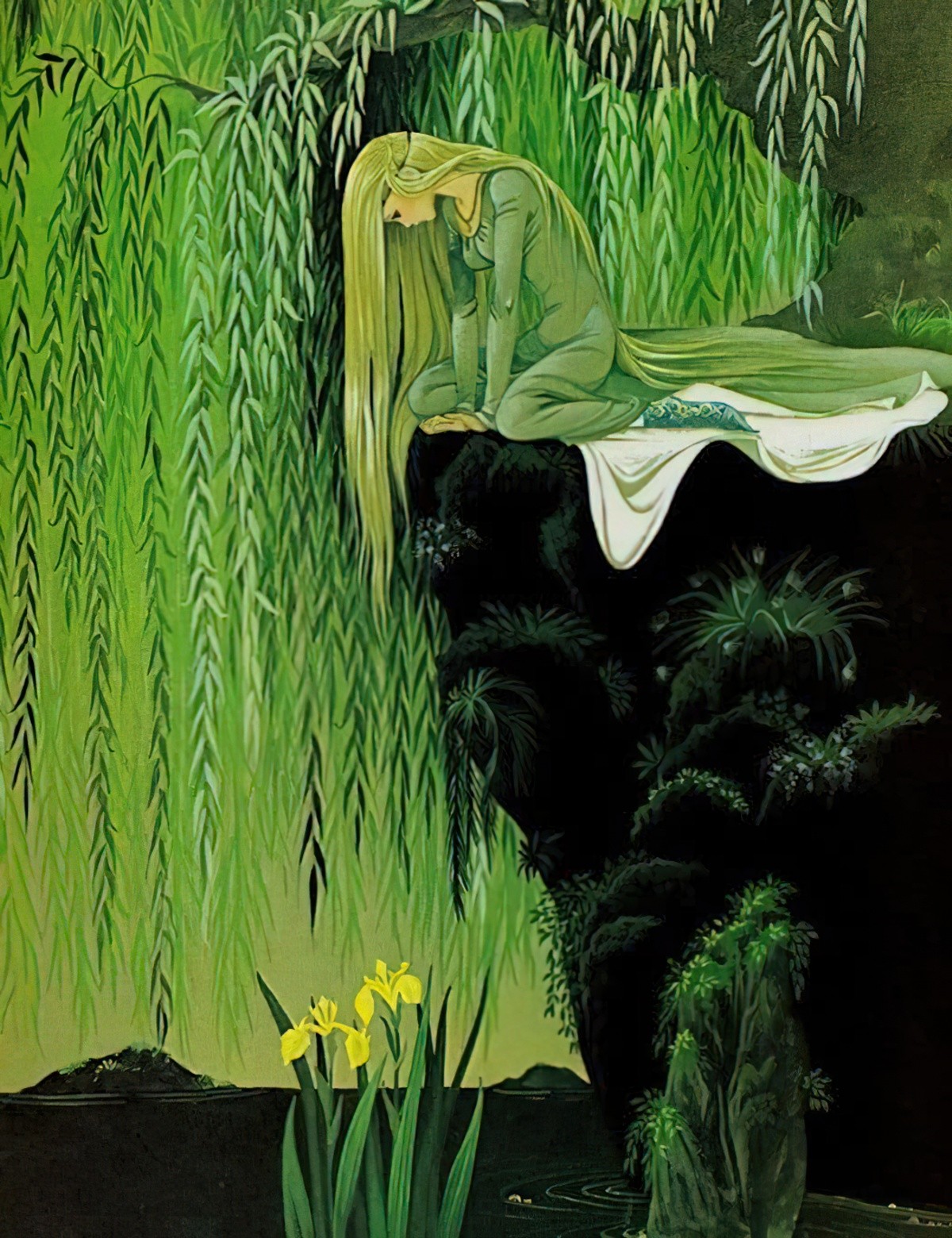

Since the Greek myth of Narcissus it’s difficult to read a story about a solitary figure next to a pond without assuming a degree of vanity. This beautiful princess, the youngest of seven daughters, is the most beautiful of the lot. Often in fairy tales the beauty equals goodness, but in this particular retelling, her beauty equals self-absorption and vanity. She must be punished for such narcissism.

The golden ball is a metaphor. If she does not find a suitor of means, she will be left destitute after her father dies. Women are not human in their own right because the father will entail his fortune to the nearest male relative a la Pride and Prejudice.

This princess isn’t literally playing with a golden ball. She is sitting near a body of water mulling over her ideal suitor. In some stories the body of water is a well. No surprise, since wells are associated with wishing. When the frog dives deep into the water to retrieve the ball, he is promising release from economic precarity. This is not about a toy ball. However, like any deal with the devil, there’s a catch. In exchange for economic support, she must provide offspring and sex.

SHORTCOMING

The Princess is a liar. In a kinder reading you might say she is capricious, but this Ladybird retelling leans more towards ‘liar’. She needs to learn to keep her word.

FROGS AS FEMININE DISGUST OF MEN AND SEX

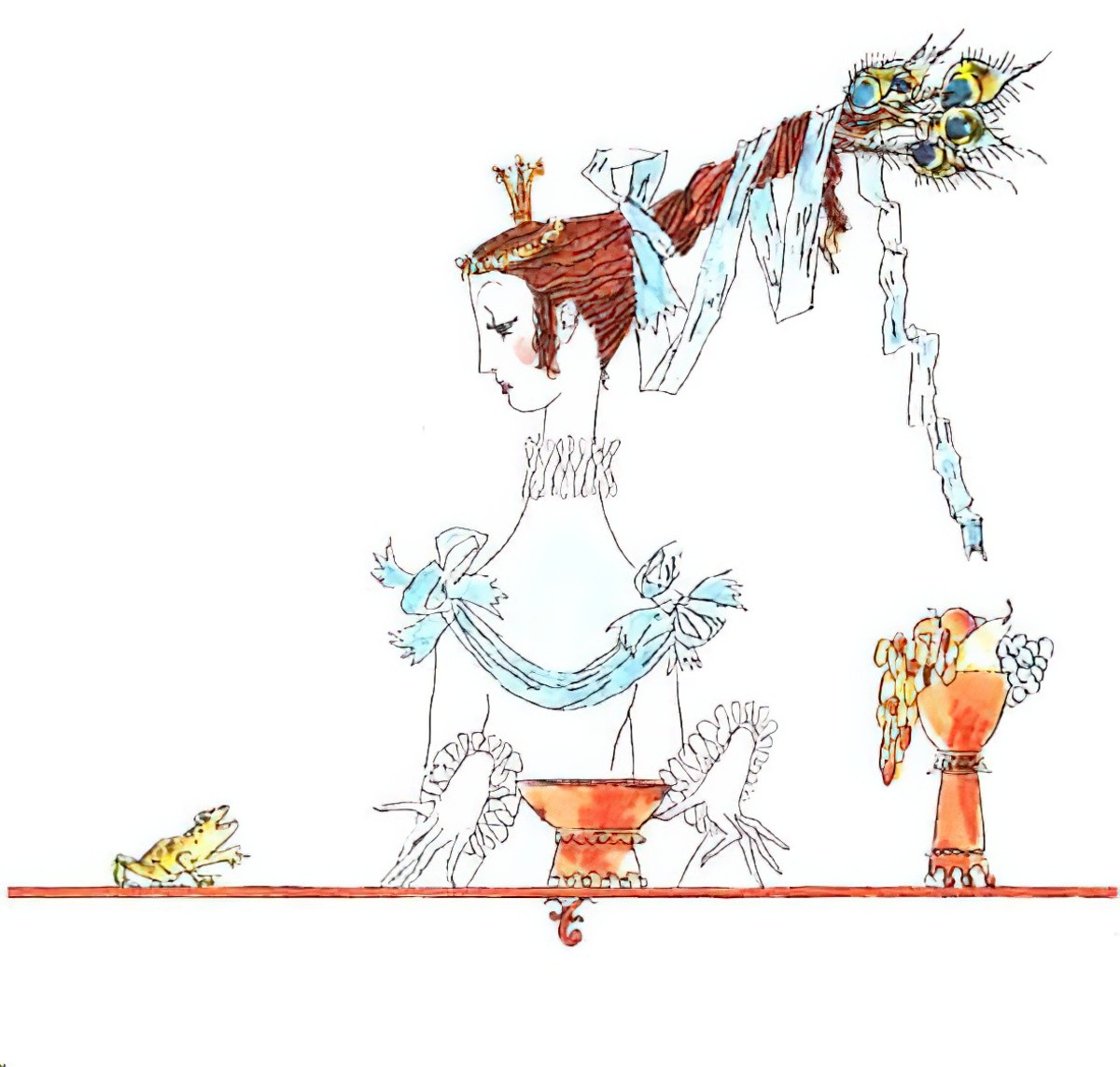

If we take a look at the wider corpus of illustrations containing both a frog (or toad) and humans, overwhelmingly, boys are fascinated by amphibians while girls and women are disgusted.

And if frogs are associated so strongly with healthy, curious boyhood, and with feminine disgust, what are we to make of this fairy tale? Which part of the anatomy might the frog represent?

The fear of childbirth is now known as tocophobia. In the age of the Internet, women have been criticised for sharing stories of childbirth online and therefore inducing new tocophobia in other women, but the variety of fairytales such as The Frog Princess show us clearly that women have ALWAYS been frightened of childbirth. That’s because childbirth is frightening.

More widely, we might consider fear of engulfment as a liminal space between girlhood and womanhood — a period of unguarded impulses, savagery and cruelty in sexual love, mixed with the desire for security and and protection. Katherine Mansfield’s young women are often said to be in this space, afraid of adult relationships, wishing to remain in an emotional state of childlike fantasy.

Beauty and the Beast is another example of a ‘death by engulfment’ tale. This traditional belief about how female desire works can be seen in Beauty and the Beast and Ricky With The Tuft. In his conclusion of Ricky With The Tuft, Charles Perrault specifically explains to the reader that the magic in his story is simply a metaphor for the way women are inclined to fall in love. Though men always seek physical beauty, women look instead for virtue and some kind of essential goodness.

“Men like young, beautiful women but women like older, powerful men.”

This view of female sexual desire has been so pervasive throughout the history of literature that it may have even succeeded in persuading young women themselves. Which is exactly why a story such as The Frog Prince would have come into existence. When women literally belong, as chattels, to their husbands, it is one challenge of man to indoctrinate their daughters into believing that whomever the father chooses for her on her behalf is indeed the best choice, even if he does not seem so at first.

DESIRE

She has no overt desires of her own. Instead she is involved in a chase, a potential victim of arranged and unhappy marriage

OPPONENT

The ugly frog, who she does not want to marry. In a romantic plot, the man and the woman are each others’ opponents. The King is also the opponent of the princess, for wanting what the frog wants.

PLAN

After getting her ball back she has no plans at all. She wipes all memory of the frog from her mind. The frog has other plans. His plan is persistence. There are so many ideological problems with persistence.

BIG STRUGGLE

The frog turns up at her door and inserts himself into her life with her father’s blessing.

She barely touched her food and each mouthful seemed to choke her. The frog, however, enjoyed every bite he ate.

It’s well known that in children’s literature, food basically equals sex. Mull on that for a minute.

Even when a girl is crying, the frog’s needs come first:

When he had finished eating, the frog turned to the princess and said, “Now I am tired, please take me to your room and we will lie on your little, silken bed and go to sleep.”

At that the youngest princess burst into tears. She did not like to touch the cold, little frog and she could not bear to think of him beside her in her own bed.

Note that the princess doesn’t like him because he is ‘cold’ and ‘little’, but those are the very attributes the reader is encouraged to sympathise with.

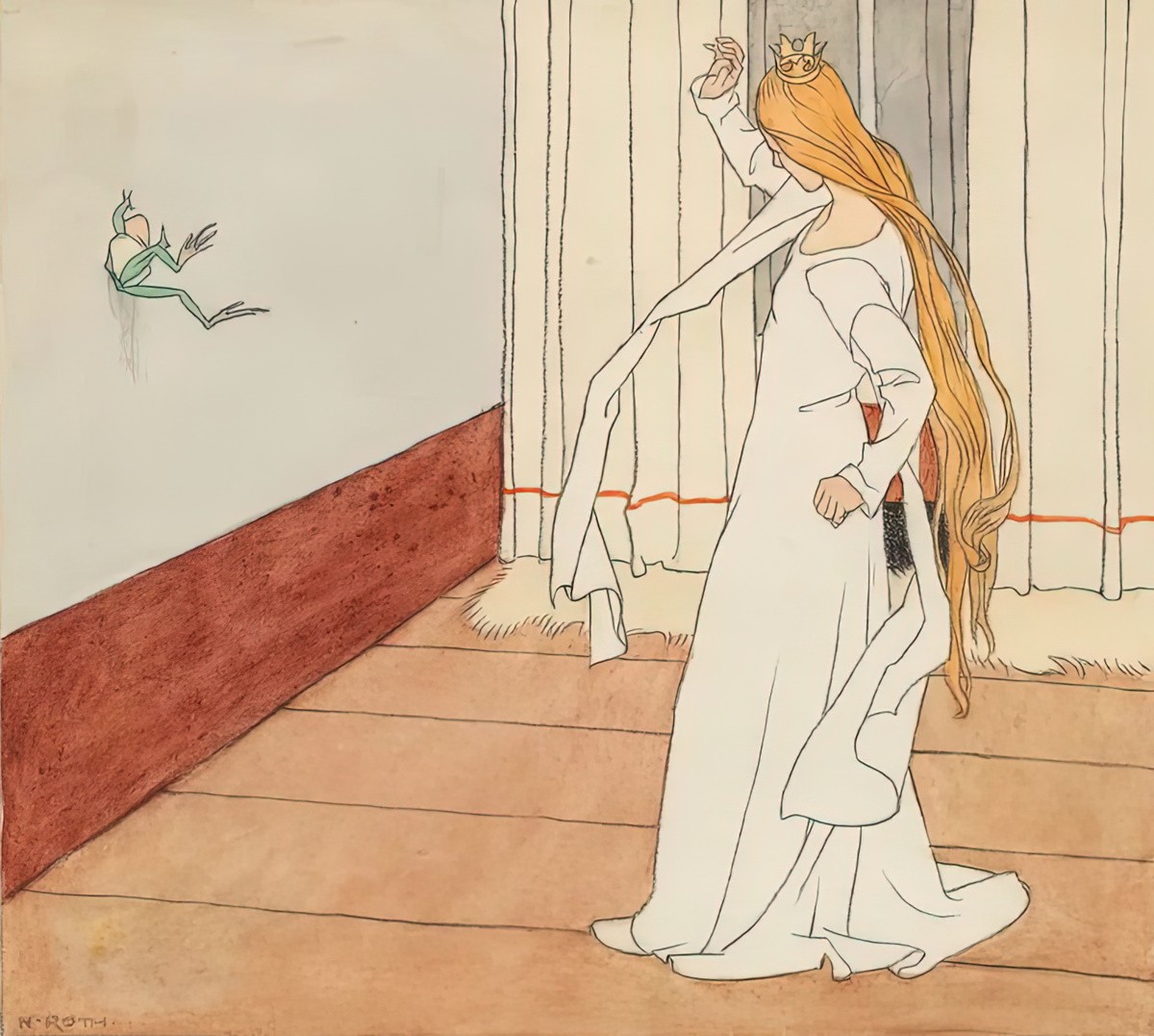

Notice how the Ladybird illustration omits the majority of the bed. It is far more confronting to show the princess and the frog in the bed together. Arthur Rackham didn’t shy away from it. Again, the perspective is from the frog’s point of view, but this is slightly shocking. Because if you’re a frog looking at a girl in her bed from the feet up, as if approaching the bed, you probably should be shocked.

FROG TO PRINCE

The frog turns into a prince and she realises she loves him now.

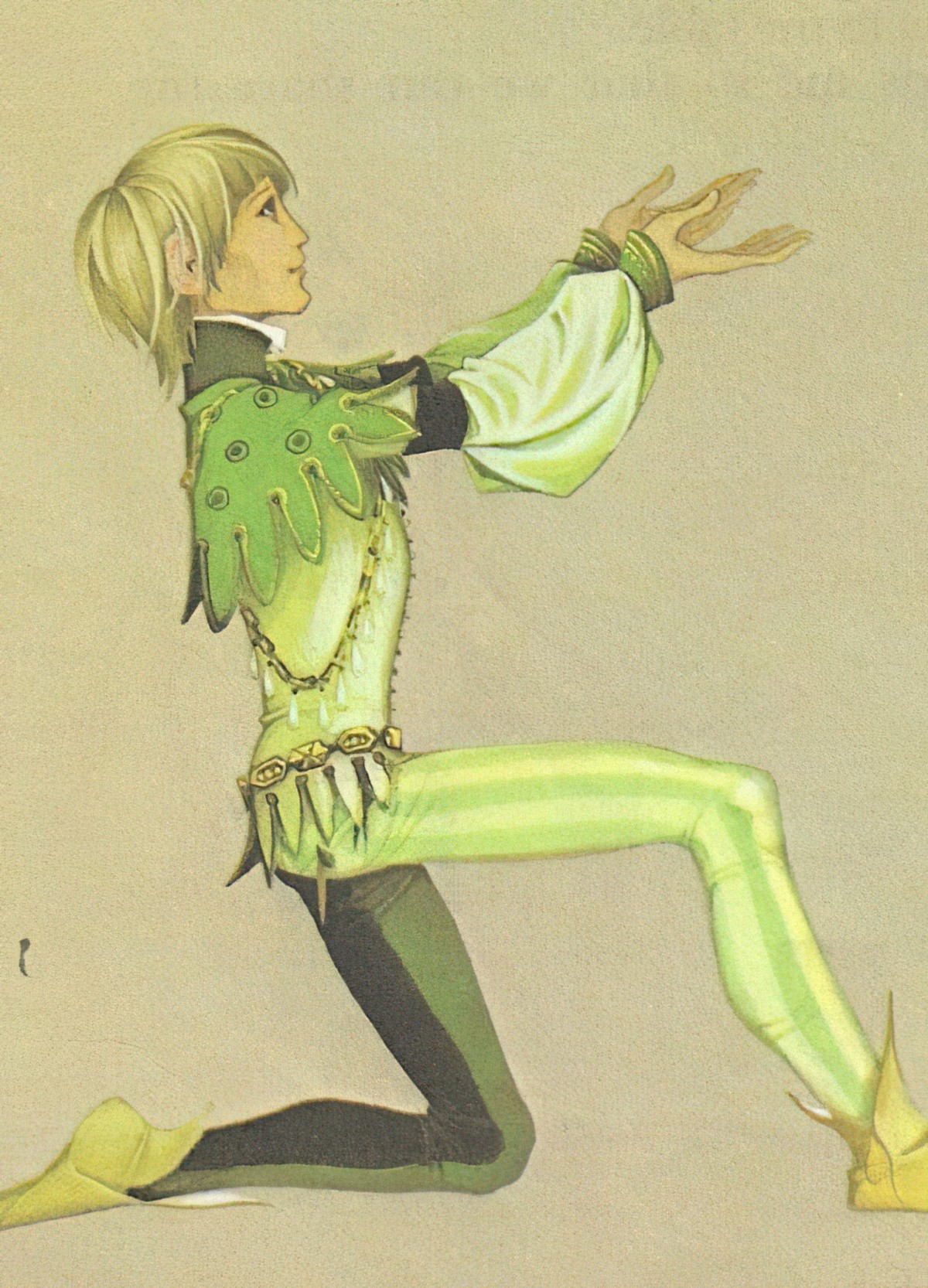

Illustrators vary when depicting the age of the human prince. In a Ladybird edition, this guy looks at least 35, while the princess looks about 15. Creepy.

But in 1977, the Johnstone sisters decided to make the prince look about 10-12 years old. When the princess herself is very young, this is a less creepy choice.

My reading of the text is uncomfortably sexual; after sharing her bed with a male character for the first time, suddenly she is in love. Probably because she hadn’t read Peggy Orenstein’s Girls and Sex.

NEW SITUATION

Frog and Princess get married and the prince takes her away to his own family’s palace in a different kingdom. The princess has officially been married off as chattel.

The Disney Movie Adaptation

I can’t bring myself to watch it, but this snippet sums it up to save me a few hours:

[Disney] strayed waaaaaay too far from the central motifs. No spoiled princess, no pact that ends with the girl having to share her bed with a reptile, no violence integral to the story – in many versions, the frog becomes a man after the girl has thrown him against the wall in disgust and anger. There was violence in the Disney movie, but it was parenthetical, and banter is a poor substitute for real conflict.

Soapboxing

What would an excellent retelling of The Princess and the Frog look like to me? Regardless of the plot, the re-visioned story would require an inverted set of moral lessons:

- Girls are allowed to change their minds.

- A man’s sexual desires are not to be placed above those of a woman expected to fulfil them.

- Beauty does not equal spoilt-bratishness; nor does it equal goodness. Beauty is what it is, but naivety and isolation might indeed make you the target of some predator in the woods.

- A girl/woman is in charge of her own sexuality. She knows what she wants and does not need to be coerced by any men in her life. One night with a man doesn’t transform a woman. The penis is not a magic wand.

- A marriage based on deception and coercion never leads to a happy ending. If the story followed this princess to her castle, we’d find she leads a miserable life with this entitled deviant of a man. (And I suspect he’d turned into a frog for a very good reason in the first place.)

FURTHER READING

This tale irritates the hell out of me. As catharsis I wrote my own. It’s called “The F**k Princess“.