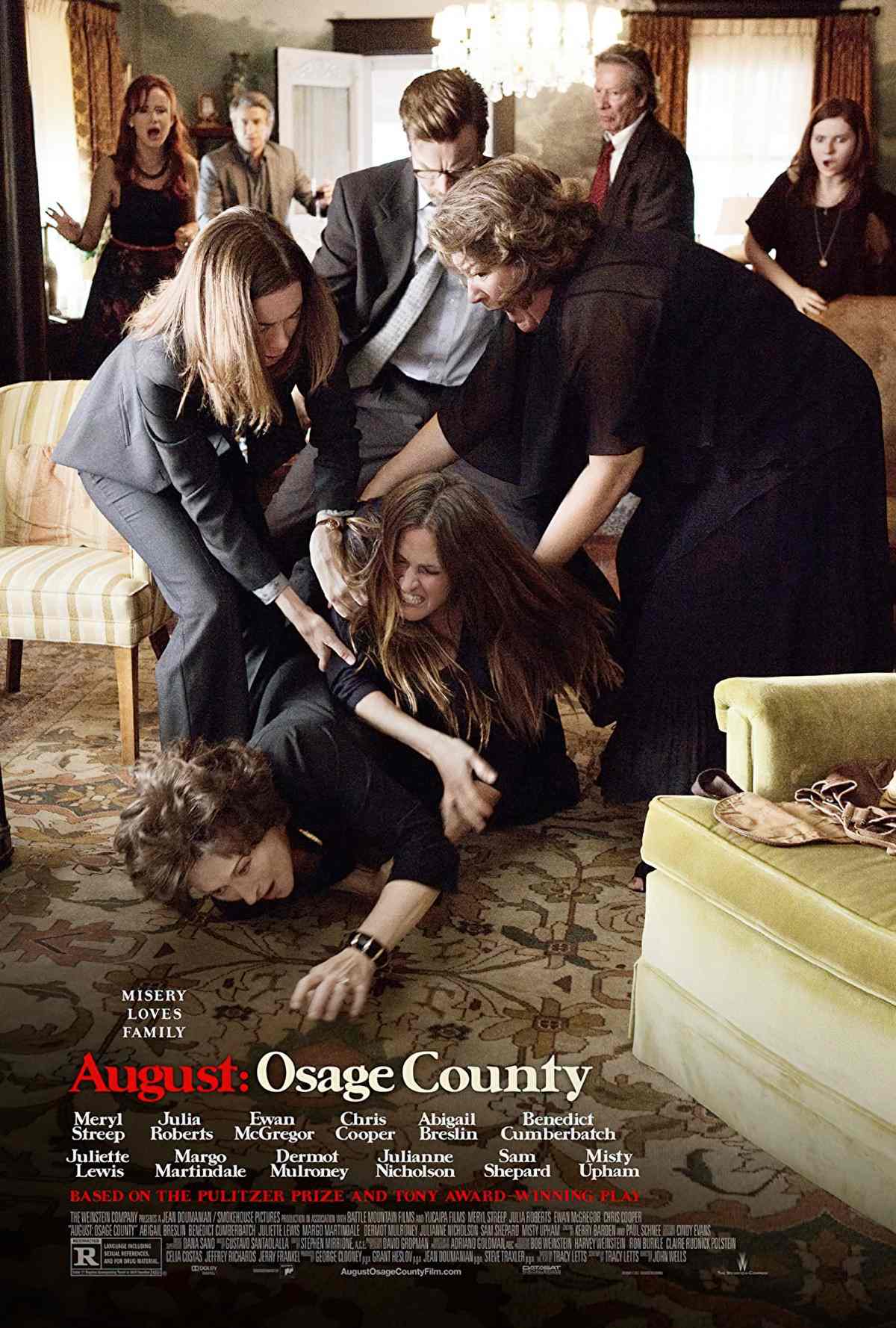

August: Osage County is a tragicomic stage play written by Tracy Letts, who also wrote the screenplay. He won a Pulitzer for this one. The film 2013 adaptation stars Meryl Streep, Julia Roberts, Chris Cooper among other strong cast. (Letts is himself an actor. He played Lady Bird’s dad in Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, for instance.)

Exhausting though it is, August: Osage County is a fascinating case study in storytelling. In this post I touch on:

- Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (Is it better to know things?)

- How the story maps onto the ur-text of Pride and Prejudice

- Family lineage and the theme of fate (intergenerational trauma)

- What society counts as proper and acceptable love

- Reveals, reversals and how they link to the central theme of truth-telling

Most of all, I’m interested in how the reveals are managed. I watched this film three times (over as many years) and each time got something new out of it. Partly, this is because I’d forgotten all of the big reveals. (The advantage of a faulty memory.) Partly though, the story itself rewards the repeat viewer with extra insight.

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How would you describe the marriage between Violet and Beverly?

- Did you find levity in this tragic tale? If so, at which parts?

- Do you see intergenerational issues continuing down the line, following the daughters? In who, and in what ways?

- In which ways are the family dynamics of the Weston family universal, and in which ways are they specific to the Westons of Osage County?

- Did you feel any of the characters were more sympathetic than others? Why?

- What role has religion played in shaping the Weston family?

- Aside from religious ideas, do you see Oklahoma in any of the characters? Which characters, how?

- Irony undergirds this story. So does hypocrisy. What hypocrisy do you see showcased in this story?

- How is the weather and season utilised at a symbolic level?

- What are the three big reveals, and were you surprised at any of them?

TRAGICOMEDY

August: Osage County is an example of tragicomedy. But what does it mean for a story to be ‘tragicomic’?

Apparently it’s all in the name: a play or novel containing elements of both comedy and tragedy.

Wikipedia expands the definition:

Most often seen in dramatic literature, the term can describe either a tragic play which contains enough comic elements to lighten the overall mood or a serious play with a happy ending. Tragicomedy, as its name implies, invokes the intended response of both the tragedy and the comedy in the audience, the former being a genre based on human suffering that invokes an accompanying catharsis and the latter being a genre intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter.

Tragicomedy entry at Wikipedia

This story does not have a happy ending, so if we’re categorising tragicomedy, August: Osage County must belong to the first category: A tragic play with enough comic elements to lighten the overall mood.

Did you pick the funny parts? My favourite parts:

- The banter between Mattie Fae and Charlie, as she tries to get him to feel her sweaty back

- Violet pointing out to Ivy that the only woman beautiful enough to not wear make-up was Elizabeth Taylor, “and she wore heaps!”

- As newly anointed family patriarch “by default”, Charlie must say grace. He clearly has no idea how to do this.

- “You never know when someone might need a kidney.”

- “Hindsight’s always twenty-twenty, isn’t it.”

Looking at my list, it’s newly apparent how many of the best one-liners are Violet’s. In the short time he was alive, Beverly was also full of one-liners. In this way, at least, they must have been a good match.

With one or two big exceptions, the characters despise each other. My feeling after watching: Those people are exhausting. Meryl Streep’s character is so toxic she casts a binding spell of negativity over the entire family, lasting decades, infecting the next generation. If this film contains humour, it’s the humour of recognition. This is what families are like. The family of August: Osage County is an exaggerated, terrible version of common family dynamics:

- Returning to your natal family home and immediately forgetting your adult self, infantilized by a parent, settling immediately into a teenage version of yourself, normally shucked off to survive in your separate, adult, faraway life.

- Adult siblings who share a childhood, but nothing much since.

- The motherly aunt who swoops in during a crisis and bustles around getting everyone organised, on a different emotional plane from everyone else.

- The toxic, abusive mother figure who appears whacked due to addiction but who nonetheless knows exactly what’s going on. Knowledge of the truth is what makes her toxic, like a contemporary version of Eve, who apparently would’ve been better off if she hadn’t eaten from the Tree of Knowledge.

- The Mr Bennet father figure (a la Pride and Prejudice) who sits back and lets family events wash over him, ensconced in his study with his head in a book, surrounded by a household of women who he no longer even tries to fathom. Like Mr Bennet, Beverly Weston has an ironic, sardonic sense of humour, showcased in his opening lines.

- An ageing parent who wishes to do a death clean (to borrow the Swedish term), and tries to push unwanted household items onto children.

- An ageing parent guilt tripping their kids for how easy they had it, when they went out of their way to make it so.

- The new member of the extended family redirecting an awkward dinner-table conversation by complimenting the delicious food.

- The predictable argument that takes place between a three-meat-meals a day guy and the vegetarian teenager who doesn’t eat meat for ethical reasons

- Arguing about whose responsibility it is to stay close to ageing parents

- A parent who turns any criticism back around on their child. It is always the child’s fault for having been born, keeping the parent from taking a more interesting, more glittering life path.

See: 1984 Wendys advertisement Violet misremembers as “Where’s the meat?” (YouTube)

THE THREE REVEALS OF MODERN STORYTELLING

This definitely applies to dark stories — mysteries and thrillers — but character driven drama can also make good use of the pattern. Note the rule of three is at play. The film is two hours long exactly, not including credits.

- At about the midpoint there’s a reversal, meaning something happens to make the audience think about everything in a new way. At the 48 minute mark (almost halfway) it is revealed to the audience that Ivy and Little Charles are romantically involved despite being cousins. This is not just a reveal about Ivy. It says something deeper about the complications of ‘closeness’ (and distance).

- A big reveal (often called a twist) to follow. At one hour thirty (three-quarters of the way through) we get the second reveal, which builds on the first: Ivy and Little Charles aren’t cousins. They’re half-siblings.

- In the last five pages (of a novel), something else crops up. At one hour forty-seven, thirteen minutes before the end, Violet tells Barbara more of the story around Beverly’s last day alive. They were both addled. Beverly left a note with his intentions. Instead of driving to save him from killing himself, the mercenary Violet went straight to the locked box.

Reveals, reversals and twists are deceptively difficult to write. Writers tend to start with the last twist then work backwards, layering everything in. Especially when writing the mystery genre, they must deliberately misdirect the audience.

The misdirection of the midpoint reversal: Before we see Little Charles alone with Ivy, we see him with Charles, in an especially fatherly moment. The scene at the bus-stop reinforces to the audience that Charles is the father. (We assume biologically, by extension.)

SOUTHERN GOTHIC

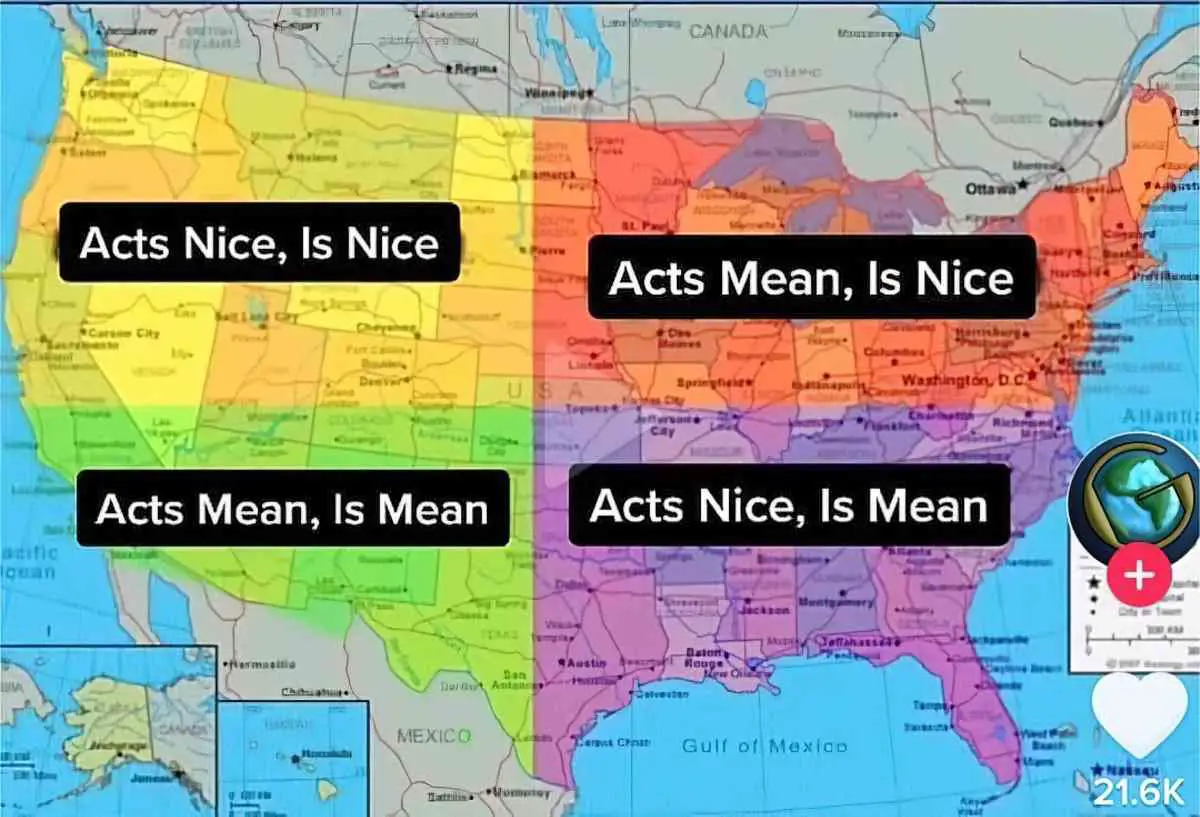

I had to check Oklahoma counts as “Southern”. (It does.) Oklahoma also counts as “West South Central”.

One of the great subjects — or, possibly, recurrent obsessions — of twentieth and twenty-first century American theater, from the works of Eugene O’Neill to Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller to Edward Albee and beyond, is the tortured family awash in denial, its members united in their inability to confess, confront, or transcend their most painful secrets and truths, at least until the final act. The similarity of such stories to Gothic fiction, with its long shadows cast by unspeakable and unspoken sins of the past, is striking, though “serious” American drama’s enduring preferences for contemporary settings and stage realism have largely excluded most Gothic conventions and devices, especially the supernatural.

Christopher Weimer

Misdirection of the second big reveal: Charles and Mattie Fae appear to be very happy together. They are the happiest long-term couple.

Misdirection of the third big reveal: No misdirection. it’s simply been so long since Violet mentioned that box we’d almost forgotten about it.

How did I decide which reveals to list as the main ones? Well, those are the ones which surprised me. Other reveals happen alongside the incest through-line, but those work differently. The audience is already in possession of the facts, before facts are revealed to characters. (The audience is in ‘audience superior’ position.) Namely, the reveal that Steve has been grooming Jean. We could see that happening all along. (This makes Johnna our choric figure, seeing what we see, positioned between audience and the rest of the cast.)

WHAT DOES GROOMING LOOK LIKE?

Since kids on this site keep spreading misinformation about what grooming red flags look like, here’s a bunch of stuff that can be actual red flags.

Some of these happening in isolated incidents may not be grooming. They could be trolls, or people whose social skills aren’t great. But if a lot of these are adding up over time and dependent on secrecy, that’s a sign to worry and tell an irl adult you trust.

As a preface, know that being groomed, abused, sextorted and so forth are NOT YOUR FAULT. It’s the fault of whatever adult creep manipulated you and misused your trust. You didn’t deserve it and you are not to blame for what happened.

Predators are manipulators who are often charismatic and charming out in public, that’s why people are shocked and don’t believe it when allegations arise. They bank on that disbelief and anger to silence their victims.

For people who don’t know about these red flags, be wary of adults who know you’re a minor and DM you, tag you or come into chats with nsfw material/genital photos/inappropriate photos Ask you personal questions about your body Compliment your looks or tell you how mature you are for your age Ask you for pictures or videos of yourself Ask for nudes

Say sexual things that make you uncomfortable and constantly ‘forget’ they shouldn’t Present themselves as “safe adults” whose followers/following are mostly minors Talk to you about wanting a relationship Try to convince you that they’re your closest, ‘bestest’ friend

Lavish you with gifts, online fundraiser donations, etc. Tell you to keep the relationship secret Want to meet you irl, either by coming to your home or meeting you at a chosen location Talk to you about topics or making you a confidant for secrets that aren’t age-appropriate

Threaten harm if you try to break off contact (ie “I’ll start cutting again if you block me!” “I’ll unalive myself if you block me!” “I’ll post your nudes if you block me!” “I’ll murder your pet if you block me!” “I’ll sh00t up your school if you block me!”)

Put the onus on you to not ruin the relationship by telling someone (you’re not, they ruined it by being a creep, tell on them!!!) Seem to want to move your communications to another platform, especially if it makes conversations more private or harder to save/share.

Note that when I talk about adults targeting you with nsfw content, I mean they specifically send it to you privately or tag you in it. Somebody posting something gross where you happen to see it while surfing a tag or scrolling their profile is not the same thing.

@GojiraSpouse

Gojira Spouse shared these links, which focus on online grooming:

- Online Grooming: What Is It, How Does It Happen and What Your Family Needs To Know

- 6 Stages of Grooming Adults and Teens: Spotting The Red Flags

- What Parents Need to Know About Online Grooming

- Sextortion

HOW USEFUL IS TRUTH?

No one has the absolute truth. To put it in old religious language, that would be idolatory, to say you know the truth, to say you’re certain. And by the way, the interesting thing about people who say they’re certain, then you need no faith.

Rev. Robin R. Meyers, Ph.D. American Heretics (2019)

August: Osage County takes a deep dive into truth: When is truth helpful? When is it better not to know? Who owns family secrets? How many of your own secrets belong to the next generation? When is meanness disguised as ‘truth-telling’?

PARATEXT

A look at the lives of the strong-willed women of the Weston family, whose paths have diverged until a family crisis brings them back to the Oklahoma house they grew up in, and to the dysfunctional woman who raised them.

logline

The tagline suggests dark comedy:

Misery loves family.

tagline (an example of paraprosdokian, riffing on “Misery loves company”)

A paraprosdokian is a figure of speech in which the latter part of a sentence, phrase, or larger discourse is surprising or unexpected in a way that causes the reader or listener to reframe or reinterpret the first part. It is frequently used for humorous or dramatic effect, sometimes producing an anticlimax. For this reason, it is extremely popular among comedians and satirists such as Groucho Marx.

Wikipedia

SETTING OF AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY

Everything I say here about the state of Oklahoma comes from a 2019 documentary called American Heretics: The Politics of the Gospel. After watching this documentary I understood how the character of Violet is the personification of a certain Southern Baptist branch of American Christianity:

- Oklahoma is considered the buckle of America’s Bible belt. (Note: The character of Violet does not seem overtly Christian, which is a commentary on how un-Christian and uncharitable Southern Baptist “Christianity” can be.)

- Oklahoma is a populist state, proud of its ability to pull itself up by its own bootstraps. (Notice: The story-within-a-story, in which Violet’s mother gifts her the old men’s work boots.)

- In Oklahoma, politicians frequently talk about family values. While talking about family values, conservatives pass legislation which make life harder and harder on families. Cuts in education spending, mental health etc. have continued to exacerbate inequality in the decade since August: Osage County was made. (Notice: Violet is the most ungenerous person. She does not believe her own daughters deserved the privilege of a university education. She expected them to do better than they have, that education was a waste unless it led directly to riches. She tries to sell her own daughters her old, unwanted furniture after telling them she’ll be taking their inheritance off them.)

- The people passing these laws believe that what someone believes is more important than what they actually do. So long as you believe in Christ as Lord and Saviour, the Lord will provide, apparently. Ergo, no need to fund social services. (We can’t say for sure what Violet’s religious thoughts are, though the dinner table scene gives us a strong clue. She’s far more interested in judging Charles for his rambling, comedic attempt at a prayer than about actually speaking to the Lord and thanking him for the food. She’s staring at Charlie the whole time, then giving the evil eye to the daughter’s new boyfriend, judging these men for their behaviour rather than using the opportunity to maintain a direct relationship with God herself.)

- In this form of Christianity, you put your head down. You don’t sully yourself with matters of the wider world, who will be going to Hell.

PERIOD

The play premiered around 2007. The story seems set around then.

DURATION

About a month from start to finish, with a few intense days in that time where the majority of scenes happen.

LOCATION

Oklahoma. Osage County, right there in the title. Known more generally as cotton and wheat country, this town farms cattle. We learn it’s Pawhuska when Little Charlie’s bus rolls into town.)

- God has ordained Oklahoma’s government for His purposes. (That means Christians in Oklahoma must vote Republican.) Oklahoma is arguably the reddest state in the country. Not a single county went for Barack Obama in either election. All counties went for Trump in the 2016 election. Kentucky is Southern Baptist in political orientation. Southern Baptists are quite different from their Northern Brethren. The split happened around the time of the American Civil War, but that initial bifurcation has continued all through the twentieth century. Today you see it in voting patterns, and also in theology.

- “In Oklahoma you can be a Democrat or you can be a Christian. But you can’t be both.” Bipartisan politics has sorted Oklahoma along lines of race and religion. About 70% of Republicans are white and Christian. Democrats are only 30% white and Christian.

- The link between Christianity and Republicanism is a recent thing. In the 1960s, church attendees were told by their preachers not to concern themselves with politics. Of course, the reason for this was Martin Luther King. Preachers didn’t want their flocks sullied by his ideas about racial equality.

- The sort of religion created during the Civil War supported a system of slavery. “The Bible’s pretty clear: Slavery’s okay!” (However, the exodus out of Israel was people experiencing freedom from slavery, so the Bible could be used to argue both for and against abolition.) In any case, to fight slavery, abolitionists had to fight religion. People were sold the story that the Bible is the essence of religion. This can’t possibly be the case because for the first three centuries of Christianity (post Jesus), there was no Bible. The Canon appeared in the 4th century. Canon is a 4th century creation masquerading as a 1st century eye-witness report. Paul’s letters etc. which appear in the New Testament are occasional (meaning the texts had a very specific purpose). Canon takes them out of their historical context by force and they have become self-referential (referring to each other). What happened as a result: These very specific texts were cut free from context, which meant people were free to use the texts as they personally saw fit, over and over again. Unfortunately, people in power see fit to interpret these texts in a way which maintains power for themselves and only themselves.

- “Oklahoma is viewed by the rest of the country as distinctive. We’re either your future or your past, and I’m not sure which.” (Bernard Brandon Scott, Ph. D., Philips Theological Seminary, OK, Professor Emeritus in Theology.) Dr Scott’s students come to his classes with an unthinking brand of Christianity. It’s the water they swim in, they’ve never thought to investigate or interrogate what it means to be Christian.

- The Christian Right has defined God as someone judgemental, angry, punitive and vindictive. He punishes people, is a law-giver and a judge based on a punishment and reward system of behaviour modification. (Educational researchers have shown this to be highly ineffective at best.) This punitive model is at odds with more liberal, giving and charitable forms of Christianity practised elsewhere in the USA and beyond. The Christianity of the Oklahoma Christian Right is fatalistic: Everything is determined by God, or else God is in control of everything. Liberal Christians look to things Jesus said and place more importance on individual action. What the individual does determines their life course. The famous Protestant work ethic is in line with the individual effort model: You can change things. You can make a difference. Violet evinces a toxic version of the bootstraps ideal, learned in the harshest of ways from her own mother. The boots are caked in shit. (Shit travels down.)

- Oklahoma of 2019: Income inequality is worse than ever. Oklahoma has some of the worst social statistics in the USA (drug dependence, teen pregnancy, domestic abuse). One in four children experience food insecurity. Oklahoma has the highest rate of female incarceration. This has been the case for 25 years. The divorce rate is 65%, even in the buckle of the Bible Belt. Violet and Beverley remain together against statistics, but how ‘together’ are they, really?

- The hierarchy: Humans > Animals, Whites > Blacks, Men > Women, Straights > Gays. These are the last days of the privilege white male. These guys push back against other groups rising by using fear and silencing tactics. Violet’s racism comes after centuries of race based violence. She embodies a quieter sort of racism than that seen in the Civil War, which nonetheless continues to have big consequences.

- Progressive young people tend to leave Oklahoma if they can because of close-minded, regressive attitudes and also tax laws designed to keep the masses poor. Two of Violet and Beverly’s daughters have managed to leave the state. The other has stayed, partly out of a sense of duty.

ARENA

I tend to really enjoy films based on stage plays. I can’t work out why, but it may be this: to create a story with such a limited scenery (in this case an old farm house and its surrounding yard), the writer has to be really good. There’s no papering over a substandard plot by changing up the scenery, sending characters on a nice holiday or anything like that.

(I think the exact same thing about Doubt, also starring Meryl Streep.)

We also get glimpses of the nearby town and surrounding roads, sometimes flat, sometimes undulating.

Most people who drive through the landscape don’t really see much. But the more you know, the more you see. The same thing’s true in the text. It’s flat, it’s barren, the colours are subtle, although they can be spectacular. It’s a beautiful landscape. It’s kind of primordial in a way. It’s also the most damaged landscape in the world. We only have about 5% of prairie left, so it’s a very damaged ecosystem. Somewhat like the Bible, which is a highly damaged ecosystem.

Bernard Brandon Scott, Ph. D., Philips Theological Seminary, OK, Professor Emeritus in Theology who taught in Oklahoma for decades

MANMADE SPACES

An old farm house

black walnuts and lace-bark elms. A farm once, no one’s put a plow to earth here in decades. Wrap around porches, forgotten gardens. Imposing in the gathering gloom. A single downstairs window glows.” (The film is shot in the late afternoon rather than in the evening, but the end-of-life symbolism works either way.) “The hallway, walls lined with photos of long-dead pioneer

ancestors and faded school photographs of three daughters.”

NATURAL SETTINGS

The film opens with cinematic stills of the area, grounding us in a slightly more Southern version of that Midwest, farming America we’re all familiar with, even if we’re not ourselves American.

WEATHER

The season is summer, utilised in its ironic sense. Used straight, summer weather symbolises fun and happiness. Just as often, though, terrible things happen in summer.

In this case, humidity and heat make everything feel close. Everyone feels close, uncomfortably so.

The literary Beverly Weston teaches us to look for the metaphorical meaning behind the heat:

Sorry about the heat in here. My wife is cold-blooded and not just in the

August: Osage County.

metaphorical sense. She does not believe in air-conditioning… as if

it is a thing to be disbelieved.

This ‘closeness’ is later taken to the max with the big reveal of incest. The closeness of the incestuous pair highlights the fractured, distant relationships of everyone else.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Flashes to timepieces are symbolically significant and send a subtle signal that Beverly ended his own life.

More importantly, both Ivy and Violet also believe he ended his own life, and those two are likely to know.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT (MILIEU)

The Weston farm is such a sealed-off environment it hardly matters what’s going on in the wider world of the story. The arrival of real-estate agent Steve, in particular, highlights the juxtaposition between fast-paced city life and the dilated pacing of life in rural Oklahoma.

I must disagree with Beverly, who opens with an observation written down by T.W. Eliot: “Life is very long”. Life feels short. But it would feel long, I guess, if every day passed in exactly the same way, as it would have since Beverly retired from teaching.

STORY STRUCTURE OF AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY

SHORTCOMING

When we first see Beverly Weston, it appears the character is breaking the fourth wall, confiding in us.

A cut to the new home help reveals that no fourth wall has been broken.

But the technique is masterful. Beverly is immediately a sympathetic character because:

- Audiences are like ducklings, falling for the first character we see

- Characters who open up in a confessional, self-deprecating way are always likeable

- He has a way with words, honed by many years of reading and thinking: “Violet. My wife. She takes pills, sometimes a great many. They affect…among other things, her equilibrium. Fortunately, they eliminate her need for equilibrium… Rather than once more vow abstinence with my fingers crossed in the queasy hope of righting our ship, I’ve chosen to turn my life over to a Higher Power and join the ranks of the Hiring Class.”

But as the story progresses, we understand Beverly’s actions of the past would have contributed to the lamentable situation of Violet, his drug-addicted, cancer-afflicted wife.

If Pride and Prejudice were set in 21st century rural Oklahoma, it may have ended like this, with the complaining Mrs Bennet hooked on “Valium. Vicodin. Darvon, Darvocet. Percodan, Percocet. Xanax for fun. OxyContin in a pinch. And of course Dilaudid. I can’t forget Dilaudid.” (Darvon and Darvocet have since been recalled — 2010 — because it causes an unreasonable risk of heart problems, which places this story in time, somewhat.)

And, like Mr Bennet, it’s easy to miss how this husband is actually pretty terrible, but not in the jealous, obvious, verbally abusive, abrasive way Violet is horrible. I’m reminded of “Rip Van Winkle“. We are encouraged to feel sorry for Rip, and immediately join the community’s chorus of hatred for the Dame.

Note that in her drug-addled introduction to Johnna, Violet slurs, “Oh, you hire women’s now the thing. I thought you meant the other woman.” At this point in the story, we can assume Violet is just plain mean and nasty, and accuses her put-upon husband of infidelity for no good reason. We forget she ever said it, couched as it is among other slurred words. Later we’ll learn that Beverly had an affair with Mattie Fae, which led to the birth of Little Charles. Violet has been required to put up with a lot.

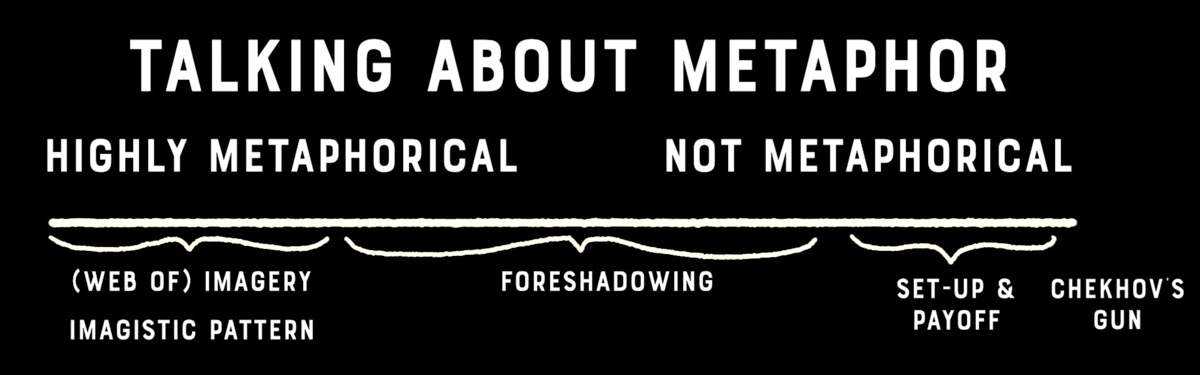

So does this bit of dialogue count as “foreshadowing”? Lately I’ve been mulling over the various definitions of foreshadowing, since everyone means something slightly different by it. Some people use it interchangeably with ‘imagistic pattern’. At the other end of the scale, others use ‘foreshadowing’ when talking about simple set-ups and pay-offs.

In my analysis of Doubt, I argue that something in a story can be all three: feeding into the imagery, an example of foreshadowing (which always has a metaphorical element) and can also function at a surface, plot-telling level.

A better word than foreshadowing for Violet’s early line would be ‘delayed decoding‘, since the infidelity does not, on its own, work at the level of metaphor. The audience only notices it after seeing the film at least once. If this were a line we were supposed to take literally, and to notice at a conscious, tuck-away-for-later level, I’d be more inclined to call it ‘set-up’, readying the audience for a later pay-off. But it’s such a throw-away line, and so slurred, disguised by other lines which literally make no sense, not even to Beverly:

Violet: In the int’rest of …civil action, your par-tic-u-lars way of speakking, I thought you meant you had thought a whoa-man to be HIRED!

Beverly: I don’t understand you.

August: Osage County

This is why Violet’s early revelation of her husband’s infidelity does not count as ‘set-up’, except for the rare, extremely vigilant audience member, that is. Hence the other problem with drawing firm distinctions on the metaphor continuum: What works as one thing for one audience member works differently for another.

This is an ensemble cast, about a family rather than any single character, so let’s briefly list the shortcomings of each of them.

But watch again as the clues accumulate, some at a symbolic level, some at a more literal level:

- Charlie points out a ‘complicated’ similarity between Beverly and Little Charles, which Mattie Fae denies on one level, “Little Charles is not complicated. You have to be smart to be complicated”

- Mattie Fae accuses Charlie of sitting round watching a ballgame drinking beers. Charlie counters that Mattie Fae is drinking a whisky. We have already seen Beverly was a whiskey man, linking these two characters together.

- We’ve also seen how Mattie Fae appreciates an intelligent book man, whereas with Charlie she’s got a man who went into ‘posters’, and has never read a book in his adult life.

Mattie Fae drops those three clues before taking off again, leaving Violet with her daughters.

I’m tempted to compare the Weston daughters to the characters of Pride and Prejudice:

- IVY: Ivy is Jane and Mary rolled into one — the sensible, kind-hearted but plain daughter who never moved far from home and whose romantic interests are also close to home. In Pride and Prejudice Mary never does end up with Mr Collins, and for this reason among others, I don’t believe Ivy will remain in romantic partnership with Little Charles.

- BARBARA: The favourite of the father due to her abilities as an academic, literary type (matching Lizzie of course, but who also seems to be Violet’s favourite)

- KAREN the baby of the family, who has a very poor taste in men (flashy, and later exposed as predatory). Karen is an older Lydia (though Lydia is spread across Karen and Jean.

Note that the only daughter who we see at her own home is Barbara. Like Violet, Barbara lies in bed in a dark, two-storied house, roused by her daughter because she’s wanted on the phone.

Fleshing out the female cast we have Johnna, invisiblised like Austen’s Kitty, but also an integral part of exposing the predatory male villain.

Going down one generation we have fourteen-year-old Jean, Barbara’s daughter, whose youthful naivety contrasts against the cynical, hard-won wisdom of her grandmother.

Mattie Fae is the kind-hearted aunt, though her history is a little different from Austen’s Mrs Gardiner.

Steve is Wickham, of course — a real estate agent ten years older than Karen who drives a flashy red convertible.

As in Pride and Prejudice, some characters in this story look truth straight in the eye while others sit with the wool over their eyes. The scene below is particularly painful to watch. Barb rips into Jean for wanting to return home early from her grandfather’s funeral. There’s a restored Phantom of the Opera she’s been wanting to see. Steve the predator inserts himself between mother and daughter, utilising their emotional distance to his own advantage.

Even more painful than that, Jean’s auntie appears, clearly jealous of the attention Steve is paying her fourteen-year-old niece, who aunties are supposed to protect. Instead, she forces the predatory boyfriend to pay sexual attention to her, instead of to the child she sees as a rival.

Everyone has something they refuse to see. Everyone except Violet, that is, who is — not coincidentally — the unhappiest of the lot. Ivy turns a blind eye to the extent of Violet’s drug addiction. Barbara can’t see her own daughter being groomed right in front of her eyes. Karen can’t see that either, that her fiancée is terrible. Charles and Mattie Fae “have never discussed” the paternity of Little Charles.

DESIRE

Also planted near the beginning of the story: Violet mentions to Barbara a locked box, with money and expensive jewellery. The supposed marital agreement: If anything were to happen to either one of them, the other would open that box.

This box is obviously symbolic — all containers are, right? — open them up and find a secret. (The box is a metaphor for story itself.) It functions as a mystery, though not the central one. The ostensible main mystery: What happened to Beverly? That’s what characters want to know.

But the mystery of Beverly isn’t much of a mystery. (I call it a McGuffin desire [to know]. It’s what kicks the story off.) The audience can deduce Beverly meant to disappear, pretty much as soon as he leaves. This is why he hired Johnna, to assuage his guilt at leaving a terminally ill wife. The mystery doesn’t even last long. We see the police turn up, that the family receives bad news. We don’t know the details of Beverly’s death because details would derail the real mystery. In another example of delayed decoding, Violet has been hallucinating visits from the police. The first time she mentions it, we have no idea where that comes from. The second time, Barbara tells Violet she’d better not get hooked on pain killers again, calling her at three in the morning to tell her about police and someone in the yard. But then the police do turn up for real, telling her Beverly’s dead. A feature of delayed decoding: It tends to suggest a fatalistic universe. Violet’s drug-fuelled hallucinations now feel prophetic.

(Note that Karen tells Barbara, who is hardly listening, that the only way to live a good life is to live for ‘now’ because you never know what’s going to happen. This feels like a character pushing back against what is actually the current of fate, set in motion the day she was born into this Oklahoma family.)

The cash box, too, is not the main mystery. These surface mysteries carry an audience along for the ride, in a story about inter-relationships: How did these characters get to this point with each other? This is the meat of the story. Characters desire connection with each other. Ultimately, they don’t know how to get it. Each character, in their own way, messes things up.

OPPONENT

To summarize, it’s each character for themself. Even when relationships look okay on the surface (Charlie and Mattie Fae, then, creepily, Jean and Steve), they are revealed to rotten underneath (snail under the leaf relationships).

The single exception to this is the sweet relationship between Ivy and Little Charles. The scene where Little Charles plays organ for Ivy is an important one, not only for the juxtaposition, showing everyone else’s relationship to be rancid, but because the audience needs to understand the depth to which these two love each other. Good luck fathoming reasons for attraction in the real world, but in narrative? We like to see it. We need to see evidence of it.

Another “I Understand You” moment has already happened, but that one was a paedophile grooming a girl he already knows to be fourteen. This dichotomy asks the audience to consider a hierarchy of ‘wrongness’ when it comes to love. Compared to this, the love between Ivy and Little Charles is wholesome and genuine.

PLAN

This is a reactive story rather than a proactive one. The central plan which kicked off the story: Beverly never meant to stick around to see Violet out, and Violet never meant to stop him.

Everyone else arrives and reacts.

Except for Karen’s creepy man-friend, of course, who has the privilege of no history with these people, and is solely focused on predation.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

I think this is a pastiche on a Wyeth painting. (Film directors love to include a scene like this. See my post on Loneliness for more examples.)

ANAGNORISIS

I’ve already listed the reveals in August: Osage County, each one leading to the departure of a daughter.

Reviewing the stage play, Brad Schreiber didn’t think much of the incest reveal, considering it hackneyed:

One wonders if there is some theatre ordinance that requires every Southern-themed play in this country to deal with incest. It is as if the fear of boring the audience has been taken to the zenith of tawdry complication.

August: Osage Country: Southern Gothic Soap Sitcom Theatre

NEW SITUATION

The ending of August: Osage County is similar to Hud, based on a novel by Larry McMurtry (Horseman, Pass By). In both cases, a mean person drives everyone away and winds up alone at a huge house in the middle of nowhere, America, surrounded by the ghosts of cattle-raising.

Except for Johnna, that is, which is ironic because Johnna is the only one sticking by Violet after Violet calls her “the Indian in the attic”.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I don’t believe the daughters will return, not until after Violet dies. Then they will come back for the funeral. They won’t want her old furniture. Too many bad memories. They’ll get a commercial outfit to clear out the house, then they’ll put it on the market. Or perhaps Ivy will move in, if she can afford to buy her sisters out.

I’ve already offered my theory on whether Ivy and Little Charlie’s relationship will survive now that they’ve been found out, and now they know they’re half-siblings. I believe we have all the information we need to know that Violet is an efficient killer. She has killed that one dead.

RESONANCE

Why are there so many stories about characters returning to rural childhood homes from the city? They resonate. Fewer of us grew up in rural areas these days, yet characters who return to remote, isolated farmhouses feel like a more exaggerated version of returning to any natal home which has become too big for our parents, rattling round amongst decades of accumulated things.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

POST 9/11 GOTHIC

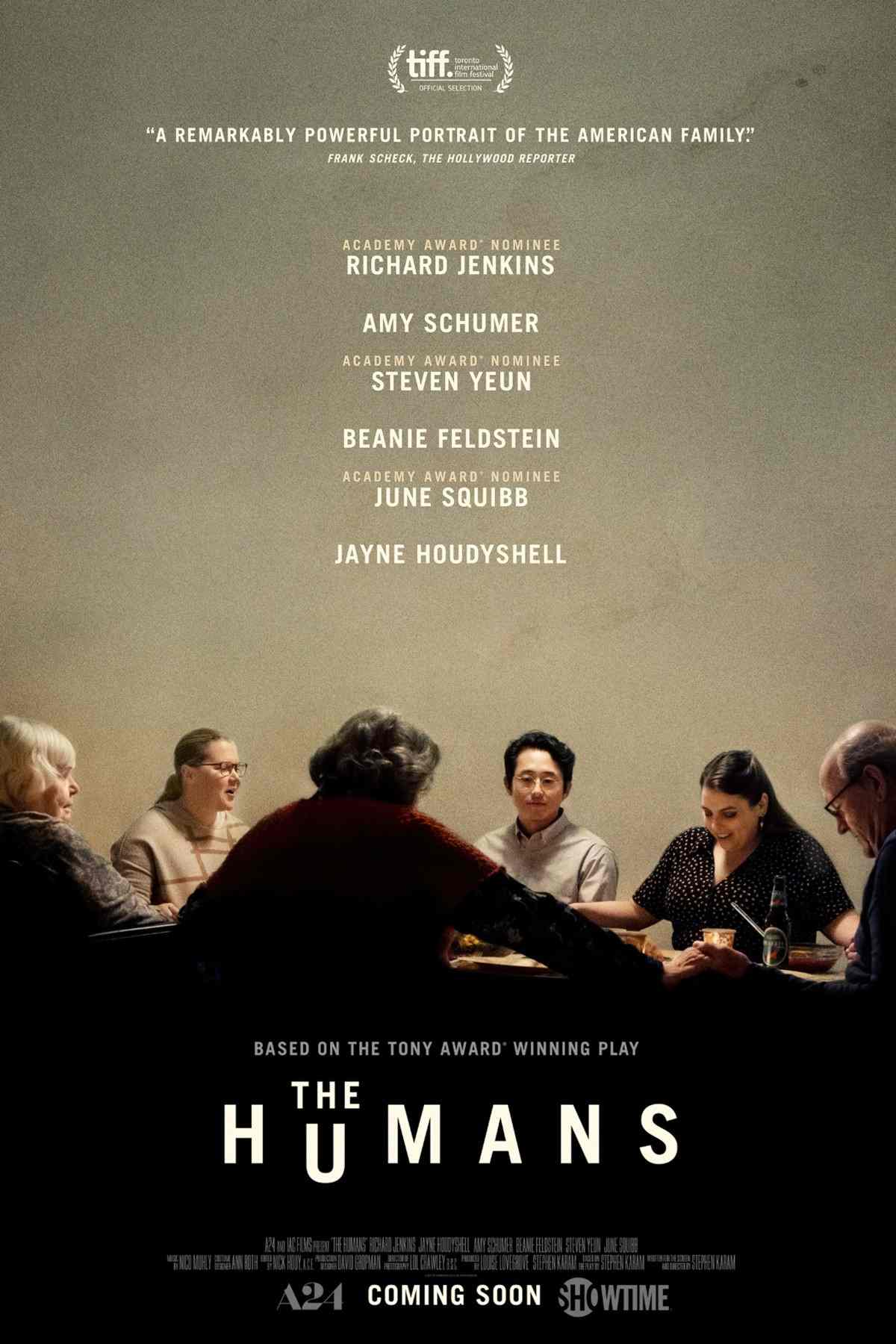

The Humans depicts the Blake family — the middle-aged Deirdre and Erik, his elderly mother, their upwardly-mobile daughters, and one daughter’s partner — gathering for Thanksgiving dinner in a basement apartment in lower Manhattan. The play’s revelations include illness, job loss, and infidelity, all underscoring the family’s precarious state in contemporary America. The Blakes are also haunted by the spectre of September 11th, the traumatic events of which Erik and one of his daughters experienced first-hand. This haunting is both figurative and, in Karam’s turn toward the Gothic, literal: in the pre-war apartment, which the stage directions explicitly describe as “a touch ghostly” and “effortlessly uncanny,” inexplicable noises frighten the characters, pots and pans crash to the floor without cause, light bulbs burn out one after another until the apartment is left in pitch darkness, and the figure of a mysterious woman repeatedly appears. […] The Humans [is] an instance of post-9/11 Gothic.

Christopher Weimer

This post is dedicated to my second cousin Lorraine, who died recently of mouth cancer after living for decades with addiction. Unlike Violet, Lorraine was a beautifully accommodating, kind-natured person. As a young woman, Lorraine was not permitted to marry the man she loved because he was not Catholic. Instead, she married a much older (Catholic, alcoholic) man called Bruce only after she was too old to have children of her own. Bruce used to swear by garlic. He took a tablespoon of powdered garlic every morning, which he also fed to his horses. Bruce was into horse-racing. The garlic didn’t do much. Soon after marrying Lorraine, he died, leaving Lorraine alone for the rest of her life.

Unlike Violet of August: Osage County, my second cousin Lorraine did not inherit the family farm. She inherited nothing. The entire estate was left to her brother, because he was a man. The brother was expected to maintain the farm and look after his siblings. He did not.