I’ve been participating in various online writing critique groups for about fifteen years. These days, some highly algorithmic critique groups work to encourage participation, gamify frequent participation and reward peer-to-peer encouragement. These are excellent.

That said, if you’ve written something personal, showed it to no one and are thinking of offering it up to a critique group, there are a number of things I’d like you to know before opening yourself up to stranger-critiques online. If you happen to be greeted by the wrong person, you may never share your work again. And every large critique group seems to have a ‘wrong person’ at any given time.

‘Critique’ Reading Is Different From ‘Ludic Reading’

Ludic reading is the experience of sinking deeply into a work of fiction, when you’re no longer conscious that you’re reading words on a page.

Critiquing does not allow for a ludic experience. Critique partners who read your work will be far, far more critical than book-loving consumers reading the same thing in published form. This type of critical reading, where something is wrong with every single sentence you’ve written, is frequently called ‘nit-picking’, and critiquers may apologise in advance for it.

However, if nit-picking is done well, it can be extremely useful. I don’t really believe in ‘nit-picking’ as a concept, mainly because the very same people who apologise for doing it aren’t doing that at all.

Critique The Work, Praise The Author

This applies to any form of feedback, but when pointing out issues for someone to change, talk about how these changes will benefit the work. In contrast, when you find something done well, praise the person, not the work. Say you’re reading comedy. There’s a gag that doesn’t work, followed by a gag that does work, further down the page.

- “This joke isn’t working yet.”

- “You really nailed this one! Haha”

Unlike a ‘shit-sandwich’ critique (good-negative-good), which many people find condescending and disingenuous, this approach is so subtle no one will feel they’re ‘being handled’. Instead, you’ll garner the reputation for being encouraging and kind in your feedback.

Some Critiquers Will Incorrectly Assume Your Intention For The Work

Some critiquers start with a set of assumptions about what you’re trying to do. They may personally believe that:

- All main characters must be likeable

- All narration must be close third person

- All punctuation must conform to North American style guides

So… when a writer deliberately writes an unlikeable main character (possibly for later subversion purposes), deliberately plays with shifts in point of view, is not even from North America, this category of critique will offer feedback on the assumption the writer has failed at what they set out to do.

Critiquers who come with assumptions of intent can be irritating, because they’ll only have advice for you to write a different type of story altogether, for a different audience. Be confident in your intent, because some of these critiquers can be very nice, and sound very knowledgeable. Many have been writing for years.

If you were sitting face to face, some of them would tell you, “Look, take all this with a grain of salt because I’m not sure what you’re going for.” That last part is implied, because long-time users of critique groups get sick of saying it.

Some Critiquers Will Incorrectly Assume Things About You As A Person

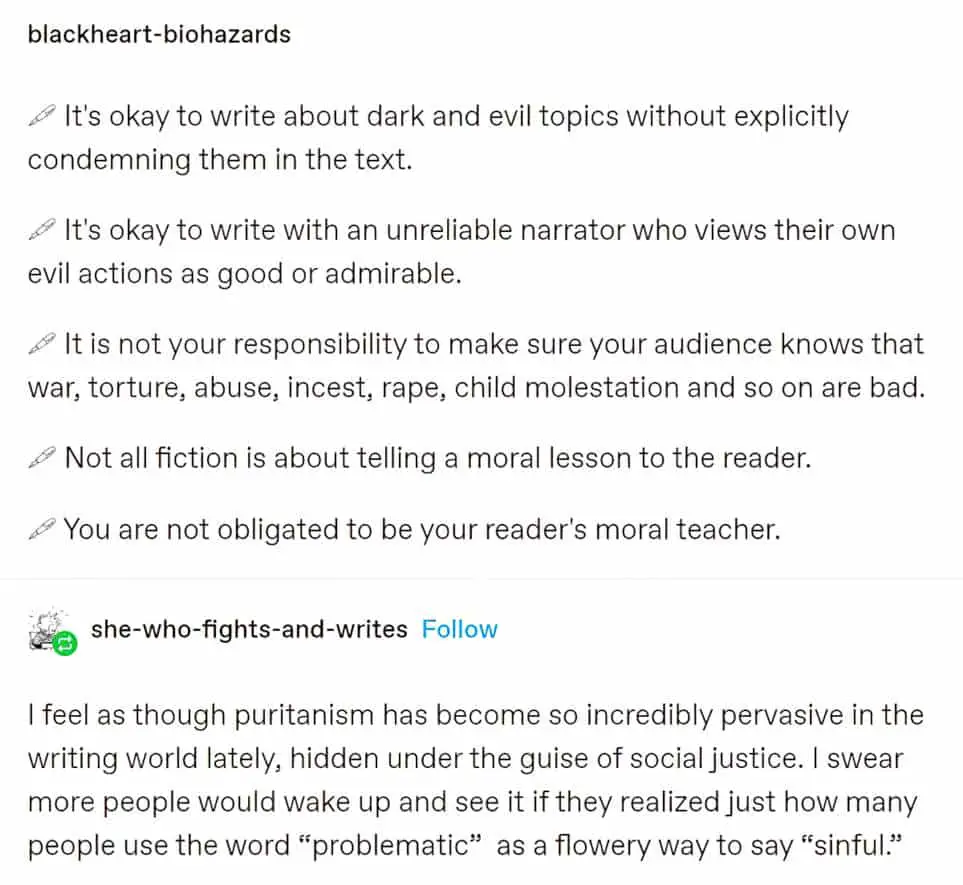

Stories which aim to subvert highly problematic ideas are particularly vulnerable to negative reactions from beta readers. Say you want to write a story which highlights sexism. In order to challenge ideas about sexism, you’re going to have to show sexism on the page in your work. Chapter One might involve a young woman starting work in an all-male environment. Chapter Four might start to show some push-back, in which the author’s non-sexist ideology shines through.

In order to critique it, you’re going to have to show it.

However, a beta reader in an online critique group doesn’t know you. They don’t trust you. They don’t anticipate how you’re going to subvert the sexism later on. For all they know, you’re not a feminist at all. You’re a horrible sexist person. They may declare they don’t read such crap and tell you so before ditching your effort with a disgusted flouish.

Moreover, the members of that group (in this case, probably women) bring with them a whole history of stories which do promote misogyny. They’ve been let down, time and time again. Even in a tentpole story about sexism, like Breaking Bad (which, read the right way, critiques toxic forms of masculinity) many women refuse to watch it because in order to get to the critique, they have to sit through many hours of plain old sexism. Not everyone has the spoons for that.

So some of these readers are going to get pretty mad with you, personally. This is useful information for how you may choose to roll out your story.

Be careful not to take that reaction personally. Readers bring a whole world of baggage to your work. It’s particularly painful to hear such censure from readers who you know to have the very same political views as yourself.

No One Has Access To Cover Copy

People in critique groups frequently underestimate how much we all know about a book before we crack open page one. Sure, on the odd occasion someone wanders into a bookstore and opens a random book knowing nothing about it. But even then, they’ve been attracted by the cover design and title. Paratext (title, book cover, marketing copy etc.) is hugely influential and helps us onto page one. Professional packing alone helps cold-readers trust the contents of a book.

Readers more frequently open a book because a friend or a trusted reviewer recommended it. In that case, readers may know a lot about your book: The basic plot, whether it’s inline with their own world view, whether it’s a page-turner or a slow-burn… Readers swap this information with friends and family.

Beta readers who join critique groups frequently forget about the importance of paratext when reading Chapter Ones. No draft has its final paratext yet. Complicating matters, traditionally published authors aren’t even in control of the cover and copy which will eventually accompany their own story. That’s a whole other issue, and hammers home its importance. (Paratext is so important, and such a splinter skill, that publishers don’t trust authors to write the titles and marketing copy of their own books.)

When it comes to beta reads in online critique groups, lack of paratext contributes to uncharitable interpretations. Not: “This is probably going to be good.” Instead: “This is probably going to be shit, but I’ll see what I can offer anyway.”

Also, more is being asked of a Chapter One when betas don’t have any idea what the story is about, the genre blend, what the cover might look like. Chapter Ones are very difficult to write. If you can write a Chapter One to satisfy online beta readers even when your beta readers have no paratext to help them, you know you’ve nailed it.

Not All Critiquers Are Broad, Capable Readers

Some critiquers can only enjoy work which is written in a very narrow range of what they personally find interesting. But without acknowledging that fact about themselves (which is slightly shameful for a writer to admit), these people will nonetheless offer critiques on, say, literary fiction even though they’ve never read literary fiction since being forced to in high school.

Perhaps the worst mismatch happens when a work for children is critiqued by adults who have not read children’s books since they themselves were children.

Or maybe it’s people who critique lyrical short stories, but they’ve never read a published lyrical short story in their life, thinking every short story must conform to genre story rules. I don’t know. I guess every writer is prone to attracting the wrong beta readers! We all think it happens the worst to us, and whatever we happen to write. (Another important psychological phenomenon of note! We all think our own genre is hard done by!)

A Weird, Critiquing Mindset

Some people will tell you off for writing about horrible people in horrible situations. They would not think that of a published work, but there’s something different about the ‘critiquing mindset’. These critiquers wish for an ideal world, populated with good people being nice to each other. For some reason, they think their ideal world might seem a little closer if they can persuade their critique partners to write likeable people who love each other.

Of course, this is not what good story is made of. Beware feedback encouraging you to make your story world a better place, with no other reason given.

Critiquers Are Not Publishing Professionals

Critiquers are not publishing professionals, except for the few who are, or who say they are. If someone tells you they know what they’re talking about because [X]: they used to work in publishing, or in journalism, or in academia, or they’re an English professor, first of all it’s always a red flag when someone feels the need to wave their credentials. But also, let’s talk about the basic maths. The opinion of one professional won’t trump the broader opinion of, say, 100 amateurs. This may not work in the sciences, but it seems to work in the arts, where reader response is subjective.

Ignore the people who’ll tell you if your work is ‘publishable’ or not. The entire concept is problematic. It reminds me of a ‘bikini-ready body’. It’s absolutely true that literary agents and large publishers are looking for specific sorts of things at very specific times. But literally everything is ‘publishable’, if only on someone’s own blog. Many critiquers assume your goal is to be a traditionally published author selling millions of copies to as broad of an audience as possible. Likewise, don’t even ask critiquers to tell you if your work is ‘publishable’. It’s a question I refuse to answer. (People who ask only want to hear ‘yes’.)

Ignore the self-professed publishing experts, because even people working in publishing don’t have any idea what’s going to be the next big thing, and will frequently confess (in interviews etc.) that they wish they saw more minority voices in the world. If you’re a minority voice, you’re going to cop it on a critique group, in so many ways. Telling someone their voice is not ‘relatable’ (and therefore not publishable) is another problematic thing that certain allocishet white betas like to say, without the self-insight to understand that not everything has to be for them.

Critique Groups Develop Their Own Subcultures

If you’re in a toxic group, get out. Don’t try and make it better. You’ll feel a sense of relief as soon as you leave. These people don’t deserve a better group.

The toxicity of a group may take a while to rear its head. Say, everyone seems very welcoming, but then someone writes a horribly problematic work but everyone is too ‘polite’ to call them on it. You’re wondering if you should tell this person, because you feel like the only one who notices. Get out. Tell them they’ve written ableist tripe or whatever, and then leave forever. You don’t want to be the only one in a group who knows racism/sexism/ableism when you see it. You obviously can’t trust anyone to point out the truth to you, either, should you need it someday. Find a group which aligns with your own broad political take on life.

That said, every single group larger than two people will divide into factions, and every single group will have its ‘standout influential people’. These people tend to be frequent (if not thorough) critiquers, and often very active on the discussion forum. The Cool Kids (TM). (The real cool kids of your writing group will be too busy thinking about writing, not etching their niche in the hierarchy. They won’t waste time on the forums.)

Writers being imaginative types, some will create distinctive personas and ‘method act’ their characters on the forum. You get that on any Internet forum, but chat spaces full of writerly-types may be particularly prone. I find it annoying, especially since people wearing a persona don’t have the same self-censoring mechanism. They’re taking a holiday from themselves, and the consequences for being rude probably seem less if they don’t feel they are ‘really them’. (People who switch in and out of their fictional personas are possibly even more annoying.)

Even without turning ‘toxic’, critique groups can stifle creativity when a number of amateur writers hew too closely to certain simplistic rules. Pet peeves are contagious. Ever since someone told me he can’t stand the phrase, “He held up his hands” I’ve avoided writing it myself, remembering him every time. Yet I frequently read it in published work. And I notice every time. I kinda wish he hadn’t shared his pet peeve, because now it’s one of mine.

A really, really common one, specific to writing groups: The notion that points of view may not ever shift within a paragraph. In published work, subtle shifts in points of view are common and serve stories well. I write about that here, using Richard Yates as one example. (I could have used more contemporary examples, but happened to be reading Yates at the time.) In critique groups, very few writers talk about the broader notion of ‘focalisation’, which is far more complex than amateurs know.

If writers spend significant time in a writing subculture in which pretty much everyone agrees ‘head-hopping needs to be stamped out’, it’s easy to start self-censoring even before you’ve got something down on the page. If you start imagining what your critique group will say before you’ve even written it, this is now an actively suppressive environment. (I’m borrowing a word from Scientology, I guess. Won’t be borrowing any more.)

I guess it’s a little obvious to say: Don’t listen to everything in a critique group. No one can please everyone. We learn that broader lesson from living in the world. What I’m talking about here is far more pernicious, because with something like ‘head-hopping’ (which might be a legitimate case of shifting focalisation), it can feel like literally everyone in your group is stamping the same thing out, even when it’s not actually causing readers problems. (Remember, few people in a critique group are reading ludically.)

I’m sure this group think is why writers such as Zadie Smith urge writers to keep away from groups. Critique groups are less useful for experimental writers who write open-ended stories. Ditto for postmodern work which demands deep interaction from readers, and work with sophisticated symbolism, which requires a mind trained in reading for symbolism. These works won’t be fully appreciated. But every now and then you’ll find an excellent beta who gets it. Hopefully that’ll make it worth it.

Some Critiquers Are ‘Fly-Swatters’

Critiquing someone’s writing should be hard work. If you’re not mentally stretched by it, you’re not doing it right. But people on writing forums have full-time jobs. Many have caring responsibilities. They’ve come home from work and crack open their laptop at 8:30. They’re tired. Too tired to do their own writing, but not so tired they can’t read someone else’s work and find all the punctuation and spelling errors.

bike shedding: a person faced with a job they is not capable of doing attends to largely irrelevant details to avoid facing the issues they can’t handle.

Some critiquers will be slightly drunk. If you were in a room with them, you’d know it at a glance: Ignore their rambling. They’re talking laughable shite.

Aside from basic copy edits, pouncing on point of view shifts and ‘filtering’ are other low-energy ways to submit a critique and put yourself in line for a critique yourself or feel you’re still writing even though you’re not doing any mental work.

‘Unnecessary filtering’ is a widely misunderstood writing pitfall. Applied correctly, ‘filtering’ refers to unnecessary instances of: ‘He saw’, ‘It seemed’, ‘Apparently’ etc. In true examples of unnecessary filtering, writers cross the words out, literally nothing is lost.

However, it is not also the case that every single instance of ‘He saw’, ‘It seemed’, ‘Apparently’ is an example of unnecessary filtering and needs to be crossed out. Sometimes it marks a shift in point of view. (These are particularly irritating because if you don’t include them, you’ll be accused of ‘head-hopping’. Include them, you’ll be accused of ‘unnecessary filtering.)

Tired fly-swatters also like to cross out every single instance of ‘just’, even though ‘just’ has a multitude of uses in English, including as a quasi-model verb. If that makes no sense to you, bear in mind you should not be nixing everyone else’s ‘just’, as if swatting flies. (Don’t do it to yourself, either!)

Some critiquers fail to understand that writers make decisions to write grammatically ‘incorrect’ sentences for the sake of voice. If you get someone correcting your dialect (from yours to theirs), block or ignore. I swear, this is a form of xenophobia. Those of us from smaller countries don’t do it. These writers ‘don’t get it’ and they’re unlikely to be of much help to you.

Bear in mind when you’re critiquing for others, people generally aren’t very grateful when you correct their spelling and grammar. The worse the spelling and grammar, the more work you’ll put in, the less gratitude you’ll receive. It’s basically a law. So don’t bother. If it’s full of basic errors, it’s an early draft. Unless someone says, “I’m thinking of submitting this; if you find any spelling and punctuation errors, please tell me,” don’t bother. An exception I make is when an author has uploaded clearly very polished prose, with maybe one or two spelling errors in the whole thing, I’ll point that out for them on the assumption they’re like me and would prefer to share work that doesn’t have basic errors in it.

The Best Critiques Comes From People Who Are Reading The Entire Work

Critiquers who read only the second half of Chapter 17 of your novel are going to be of very limited use. This is probably so obvious it doesn’t need saying.

However, it’s tempting to think line-level help might be useful, at least. It’s generally not. They won’t know your characters’ voices. Also, some of these mid-novel-jump-in critiquers will ask question after question, and this can be irritating, actually. If your critique service allows you to keep critiquers from jumping in mid-novel, perhaps make use of that functionality. You’ll need to put in more work to garner people who are enthusiastic about your work and are willing to swap an entire full, reading properly from beginning to end. But it’s far better that way.

Regarding the Big Picture: The most useful advice you can give/receive concerns structure. The broader you can get in your advice, the better it will be received. This sort of critique can be truly enlightening. If someone gives you this kind of critique, you almost want to kiss them. When you offer a ‘naked’ draft and someone really sees it, intuiting correctly where you want it to go, helping you make it better, this is an intimate experience unlike any other.

One useful way to make use of a critique partner: Each explain your synopsis to each other. This is hard work, for the listener and for the teller. It’s not fun. Even the best story sounds boring when told by synopsis. However, it’s an excellent way to spot problems.

In fact, you may not need anyone to listen. Try explaining your plot to yourself, or typing it out.

Explaining problems is good. Often in the process of laying out a problem, a solution will present itself.

Less Wrong

Beginner Writers Who Write Incomprehensible Prose Are The Least Grateful For Tips

No surprise, right? If they were better at taking advice they’d be better writers.

Writers who are already pretty darn good tend to be far more gracious. These people have learned to separate themselves from their work, can see their work more objectively, and don’t take criticism personally.

Some Writers Share Very Early Drafts

I am not one of these writers. I would be embarrassed to share work which barely makes sense. I usually find when revisiting a piece the following day that elves have arrived in the night to rearrange sentences into incomprehensible stew. A tiny bit of distance does wonders. There’s no way I’d bung something up on a critique site without a few rounds of self-editing first.

Not everyone waits. Some people use critique groups as motivation. They dash something off, throw it up. They need to be read. Unless people are reading their dashed-off drafts, they struggle to find motivation to write an entire book.

It’s up to betas to intuit what writers want in a critique. Unfortunately it’s like sex: Some of them aren’t sufficiently self-aware to even tell you what they want. But if something feels dashed off, assume they’re there for the cheerleading. You’re absolutely wasting your time offering a full, ‘nit-picky’ critique of something which looks like your own first draft. And you won’t be thanked for it, either.

Groups You Pay For Cut Down The Number Of Trolls

Writing is such a personal, vulnerable thing to share. Writing groups attract a certain sort of sociopath who is there to make fun of people, pointing out the clichés, laughing at your archetypes, pointing out your tropes, which they, personally, have seen a thousand times before (that’s what a trope is, yes).

In forums which don’t require a credit card, trolls tend to get regularly blocked for being absolutely nasty on the forums, or to individuals, but they’ll pop back as a sock puppet. They can’t be blocked because they have a dynamic IP.

When users are required to pay a fee, this cuts down on the sock puppetry. Members feel more accountable when someone behind the scenes knows their real name.

Use Discussion Forums To Vet (And Block) Negative People

Unfortunately, you may have to get social in order to attract likeminded betas to your work, and to find stories you’d love to critique. Otherwise I’d say, stay away from discussion forums altogether.

If you do pop in and read the odd interesting thread, you’ll soon work out who the problematic people are. They tend to be middle-aged white men, but not always. They’re there for the dick-waving. Trust me, you don’t want to know what these guys think of your work. So if the critique group allows it, block them. You’ll be happily dead to each other. (Well, you’ll be happier than them.)

Energy Travels

Someone who just received a rough critique on their own work will very often bring that same energy to yours.

Likewise, someone struggling to wrangle the point of view in their own novel will come to yours looking for point of view problems, and perhaps finding some where none exist. All of this works at a subconscious level.

If you’re struggling with your own writing and feeling negative about the whole thing, avoid repurposing your regular writing time to critique for others. Best to step away from the desk entirely.

Interpreting Running Commentary

I like to both give and receive the running commentary kind of critique, but they’re really only useful to the writer if the writer knows what to do with it.

I’m talking about inline comments with my own reactions as I read. I tell the writer where I laugh, where I’m confused, where I’ve lost the plot. The writer is getting my very first impressions. Generally we’re advised to read work twice and set it aside for a while before offering critique on it, but this is a much quicker way of doing things and so long as it’s not the only type of critique someone’s getting, a few of these are very telling.

An especially useful thing to know: What questions does your beta reader have, and at what exact point? Now, as useful as this can be to know as author, don’t assume ‘questions’ require ‘fixing’. Make sure you are clear, as creator of your own work, which questions you would like readers to be having, in preparation for the next scene or chapter.

As a concrete example, a beta reader gave me a running commentary and told me she was wondering where one of my characters was getting all of her money from. My first instinct was to explain it, right at the point she was starting to wonder. But I know to resist this impulse. I’m glad she’s asking that question. That is the very question I want her to be having, because it’s addressed in the very next scene. It would be a mistake to answer that question at exactly the point she asked it.

For perfectionist, conscientious types: When interpreting running commentary, don’t think everything that runs through a beta reader’s mind is a hint that something needs to be fixed.

Interpretation and Implementation of Feedback Are Separate Skills

Writing is a difficult skill.

Interpreting what beta readers mean when they offer feedback on your work is another, quite different, very difficult skill.

Knowing how to implement that feedback is yet another skill.

So although good writers tend to be the best critiquers, this isn’t always the case. Some of your beta readers won’t be writing at your level. However, newbies can be great. The best of them havent’ lost the ability to approach your work in a ludic way. These newbies can be extremely valuable because most of your realworld readers aren’t going to be writers themselves (unless you’re writing lyrical short stories, in which case readers and writers have a huge overlap).

Because these writing, interpreting and implementation skills aren’t the same, you sometimes get a writer whose work you really admire, but who is an utter prick when it comes to giving feedback on your own work. Rare, but there’s usually one. (I think this is more of a personality problem.)

Don’t Rely On Arithmetic

Some writers will announce: “I only change something after three people mention it.”

Why the hell you’d wait for three people to say the same thing, I don’t know. This is ‘writing by numbers’.

Use your gut, not the numbers. Why wait for three people to point out that you’ve spelt your own character’s name wrong five times? Go back and fix it, so betas can stop pointing it out.

Here’s the truth: No one will say absolutely everything they’re thinking about your work. For every critiquer who pointed out your spelling mistake, another one glossed over it, possibly because they don’t point out spelling mistakes. Doesn’t mean they didn’t notice.

I find it valuable to read other people’s critiques of a work after I’ve written my own. (Bear in mind, some people will read other people’s first, and then comment on what others have already said about your work, where they agree, where they disagree. There’s no hard-and-fast rule about this — these can be useful, but often indicate the beta reader had no idea where to start.) I frequently find myself agreeing with what others said, though I didn’t say those exact things in my critique. I happened to say other things instead, and time is limited.

Don’t count the critiques. Utilise advice which ‘rings true’.

Understanding ‘what feels right’ is harder to implement than basic arithmetic, but far more useful to writers in the long-run. It requires writers arrive to critique group with a strong, unshakeable sense of what they mean to convey, and who their writing is for. If you don’t have that, be very wary about sharing your work with strangers. It may be the case that you don’t share every single thing you write. Some writing is personal, and that’s fine.

When Have You Received Enough Critique?

At some point, you’ll start getting copyediting and not much more. When people start querying as to whether you should be using double or single quotation marks, whether certain words should be hyphenated, whether you need a stylistic comma there followed by “This reads well”, you’re coming to the end of the road with your critique partners. The piece is as good as you can collectively get it.

Alternatively, someone in your group will be telling you to put something in for clarification. The next person will tell you to take it out because it’s obvious. If you find yourself getting into these loops, with not much else of value, you’ve done a good job.

SEE ALSO

The Perils and Blessings of the Creative Writing Workshop by George Saunders.

Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write

Today I talked to Helen Sword about Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write (Harvard UP, 2017). We talk about what not enough people talk about when the subject is writing.

interviewer : “You offer the advice of forming a writing group, because writing groups are, well, just all-around terrific for helping people write as they want to.”

Helen Sword : “Exactly, and well, so I try not to be didactic about just about anything having to do with writing––I’m much more about, ‘Here’s a range of possibilities. Make a considered decision here,’ rather than, ‘I’m going to tell you what to do.’ But if I were to give one piece of advice concerning the social dimensions of writing, I would say, ‘Really, really strongly consider belonging to some kind of writing group.’ And I define a writing group as being two or more people who meet more than once to talk about any aspect of writing. So, if you have somebody you meet with for coffee once a month, one other person, and all you do is you sit there and complain about your supervisor and how you wish that they were more sympathetic to your writing––That’s already a writing group. So, it doesn’t have to be some big kind of formal thing. It’s opening yourself up to the social dimensions of writing and particularly to the idea of having supporters in your corner, having some cheerleaders, having some people you can talk to about writing who are not there to criticize you––who are there to help you.”

New Books Network

MICROPLOTTING

The most revelatory writing processes I’ve seen/practiced is a “microplotting” method used by @cassieclare and @hollyblack. It’s so much fun and collaborative. I’ve been doing it w/ a friend for a fun new project and we’ve discovered SO MUCH. And also laughed. A lot! TY C&H

Twitter is a bit limited to explain but it involves one person telling the other their story, scene by scene, and one person asking questions to fill in holes, add details, address snags or push the other to explain character motivation, emotion, etc., more deeply.

@JoKnowles

DIALOGUE SPINES

An idea from @ScottWesterfeld

When you write a chapter using nothing but dialogue and then go back snd fill in the rest later. You can come up with really strong dialogue that way.

@ButUCanCallMeZ