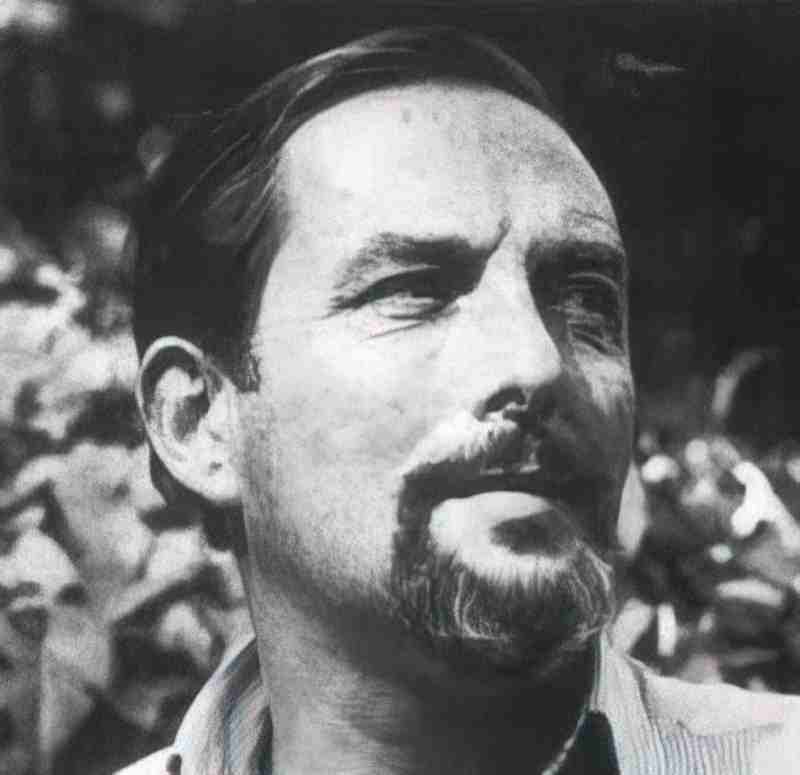

“The Vertical Ladder” is a short story by British writer William Samson (1912 – 1976) best known for his travel writing and highly descriptive language. A childhood game of dare goes wrong.

Who was William Samson?

[Samson is] a truly forgotten author, all but expunged from literary history. William Sansom was once described as London’s closest equivalent to Franz Kafka. He wrote in hallucinatory detail, bringing every image into pin-sharp focus.

Independent

The author was private school educated, then worked in a bank, then in advertising. War broke out in his youth. He fought fires in London during the Blitz. Samson’s wartime experience exerted a clear influence on his work. He returned to the subject matter of ‘unusual states of mind’.

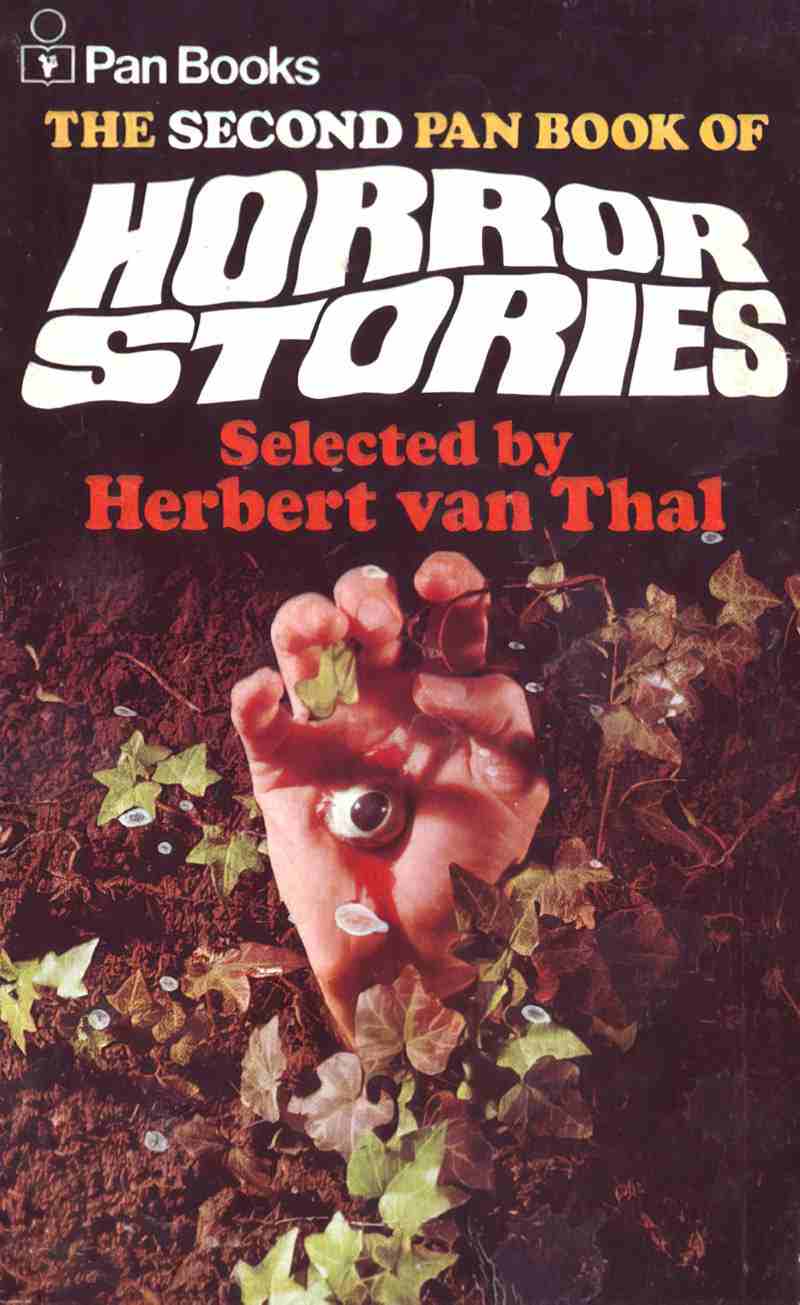

His short story “The Vertical Ladder” appeared in The Second Pan Book of Horror Stories (1969).

“Piece-meal” by Oscar Cook

“The Fly” by George Langelaan

“The Vertical Ladder” by William Samson

“Pollock And The Porrah Man” by H. G. Wells

“The Inn” by Guy Preston

“The Judge’s House” by Bram Stoker

“The Speciality Of The House” by Stanley Ellin

“The Last Séance” by Agatha Christie

“The Black Creator” by Vernon Routh

“By One, By Two, By Three” by Stephen Hall

“Boomerang” by Oscar Cook

“Our Feathered Friends” by Philip MacDonald

“Taboo” by Geoffrey Household

“The Black Cat” by Edgar Allan Poe

“Leiningen Versus The Ants” by Carl Stephenson

A glossarized version of “The Vertical Ladder” (for intermediate students of English) is available online. You can also find it at the Scary For Kids website, because this short story is the perfect length for young readers. It also concerns kid culture: The wish to show off by doing something brave/stupid.

WHERE TO LISTEN

Aspects of the author’s writing style, evident in “The Vertical Ladder”, date the story to the point where I may not teach this story in the middle or high school classroom. Notably, the following sections need addressing:

The bright green of the new leaves everywhere was too fierce on the eye; the air seemed almost sticky from the scent of busting buds. The girls had complained of headaches, and their thoughts had grown confused an awkward as the woollen under-clothes against their skins. […] Flegg wished to impress the dark-haired girl […] She had clear black eyes, with short lively eye-lids, as bright as as boy’s. Her lips opened attractively over a mouthful of rather irregular teeth, so that it often looked as though she were laughing.

“Vertical Ladder” by William Sansom

Girls and their headaches, amirite? ‘Clear black eyes… as bright as a boy’s’ suggests boys eyes are naturally bright whereas girls with bright eyes are the rare example of a worthy specimen of their sex. Barf.

Then there’s… this:

His limbs had lost much of their natural rhythm, and his body moved with the awkward movements of a cripple.

SETTING OF “THE VERTICAL LADDER”

PERIOD

New Zealand legend Sir Edmund Hillary gets a mention in this story about climbing. Hillary and Tenzig Norgay reached the top of Mount Everest in 1953, less than a decade before this was written. Kiwis are very proud of Sir Hillary. He came to one of my school assemblies once. Now he’s on the five dollar note. Perhaps we forget nowadays, how massive this accomplishment was for humanity, kind of like the moon landing.

In any case, this story was set in an era when kids were given free range of the neighbourhood, and when disused gasworks weren’t fenced-off by law.

DURATION

Ten minutes or so?

LOCATION AND ARENA

To get to the disused gasworks, the teenagers make their way through streets which become increasingly narrow. Alleyways. Why is this?

They had wandered out from a park by a back gate into an area of dirty streets.

The houses there were small and old, some of them already in serious need of repair. The streets were short and rough, with narrow pavements, and only a few shops such as a tobacconist’s or a corner store to relieve the general greyness, — it was the outskirts of some industrial area beyond. At first the quiet, almost deserted streets had seemed more restful than the park. But soon the dusty atmosphere of powdered brick, dark windows, and dry stone steps, — the extreme dryness of everything, had proved even more tiring than before.

“The Vertical Ladder” by William Sansom

The Cat Returns is a feature length animation by Studio Ghibli. In that (completely different) story, too, characters make their way through a labyrinth of streets. The word ‘labyrinth’ is key here, because what’s at the centre of a labyrinth? A Minotaur. Danger. These boys consider themselves on some Ancient Greek mission. There’s no such mission; no one’s saving the world here, let alone the town. That’s what makes the (off-page) tragedy all the worse. It’s completely fruitless. There was no goal.

See: Symbolism of the Maze and Labyrinth

WEATHER AND NATURAL SETTINGS

A classic horror trope: Characters start out having fun. The more summery, comfortable and cosy the life, the worse the oncoming horror will seem.

Even before the horror begins, the pleasant summer’s day has an unpleasant edge to it. Sure, it’s a beautiful day, but the kids are wearing too many clothes. They’re uncomfortable. The ‘air’ is sticky, but this is a transferred epithet. It’s the kids who are sticky and sweaty from their exertions.

It had been a fresh spring day, suddenly as warm as mid-summer. The sun flooded the parks and the streets with sudden heat. Flegg and his friends felt restless in their thick winter clothes. The bright green of the new leaves everywhere was too fierce on the eye; the air seemed almost sticky from the scene of busting buds.

“The Vertical Ladder” by William Sansom

What about those bright green new leaves? Another transferred epithet. (A description in a story which actually describes something else.) These kids are just starting to experience sexual attraction. They’re on the cusp of adulthood. Flegg doesn’t know how to safely deal with these feelings, and he’s about to get himself into a whole lot of bother due to maladaptive showing off!

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE VERTICAL LADDER”

When constructing “The Vertical Ladder”, the author must have decided the story didn’t open with enough excitement. Sansom must have known that, for a 1960s audience, to begin with flowery descriptions (which he clearly likes, and which early 20th century readers also liked) would lose young, contemporary readers. He got around this by snatching a scene from the climax and placing it at the beginning. This is one way of injecting suspense (and is now very common).

Flegg felt the palms of his hands becoming moist with sweat as his body seemed to become heavier with every step higher. He regretted in sudden despair the stupid events which had forced him into his present risky climb. But it was now too late. Here he was, alone on a vertical iron ladder, flat against the side of a great gasholder, and obliged to climb higher and higher until he reached the summit.

“Vertical Ladder”, opening paragraph by William Sansom

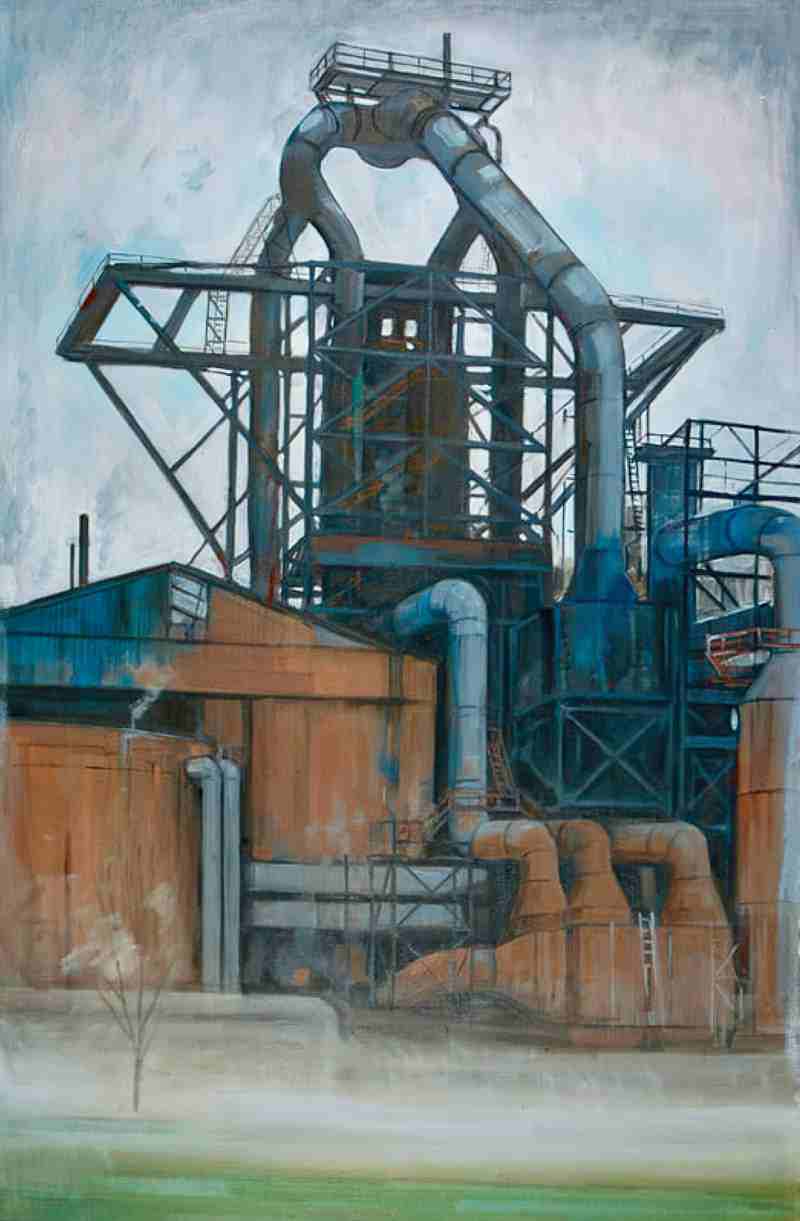

What stymies the effectiveness for me: I don’t really know what a ‘gasholder’ is? However, an illustration in the Cambridge edition helps: Imagine a massive water tank. We’ve got one next to our local graveyard. It services the entire village and is about as high as the tank in this story — ‘a five or six storey house’. You’d kill yourself if you fell off. I completely understand the horror potential for such a structure. The ladder on our local tank snakes ominously up to the top, but begins from the ground much higher than a human can easily reach. This is to save daredevil teenagers from themselves, and from situations exactly like the one Sansom describes in this story.

SHORTCOMING

William Sansom was well known for this descriptive prose but wasn’t all that interested in rounding out his characters. These teenagers arrive to us in statu nascendi, which means they are ‘without backstory’. We don’t even know how the boys and the girls came to meet. The effect: Real teenagers from real life can easily be pasted onto these characters. To individuate them would be to distance the reader.

Flegg, the kid who climbs the tower, has a short fricative name which might come straight out of an Annie Proulx story. Proulx is another short story writer who writes of terrible things that people do to each other in out-of-the-way places, and of characters who think they can conquer things, but can’t.

DESIRE

Flegg wants to impress a girl.

The girls in this story exist as spectators. Important spectators, but spectators. This is hardly an astute observation, but boys tend to show off in front of girls they like. Any allosexual adolescent of any gender is inclined to show off actually, though the forms of ‘showing off’ divide roughly along gendered lines. Boys on average show off in daredevil ways, not just for girls, but also for other boys. Perhaps mainly for other boys. However, the way Sansom sets this up suggests that if the girls weren’t there, Flegg would never have attempted the climb. What do you think?

OPPONENT

The girl is the love opponent, in a way. She soon regrets her casual dare and offers Flegg the opportunity to back out, but for Flegg it is too late. I feel Flegg may have backed out if it were only her there, but now the other boys are Flegg’s opponents. If he fails in his mission he is a coward and a braggart and a boy instead of a man.

The other girl exists as a link between characters and reader. We are supposed to feel as scared for Flegg as this girl. (I personally call these characters Choric Figures because they’ll say and do things that the audience does, too. In comedy they have the best lines. This archetype almost certainly has existing terminology. I simply don’t know it.)

PLAN

Unfortunately for Flegg, the gasholder looks way easier to scale from the ground than it actually is.

I’ve found this to be true about almost anything like this. If you think you can swim to the island, it’s further than you think. If you think you can jump across a crevice, it’s wider than you think. If you think you can jump in a puddle, it’s deeper than you think.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The part of this story that impresses me the most: How Sansom slowly reveals the Flegg’s impossible mission. The physiological descriptions of fear are also good, but the part that distinguishes this story from many other scenes like it, in which characters in action scenes are frequently terrified, is the description of the side of the unused gasholder. I could swear the author has tried scaling one himself.

ANAGNORISIS

The character realises he won’t make it to the top. That’s the big realisation.

But before that, he understands that his so-called friends are complete bastards and he never should have risked his life to impress them. They’ve taken the ladder.

He also has another epiphany, all the sadder because he should’ve had it on solid ground: He suddenly understands how the social dynamics of his social group work. The boys won’t put the ladder back because they enjoy torturing the girls as much as they enjoy torturing him. The girls are powerless to stop them.

NEW SITUATION

When you forbid someone from something, it makes them want it even more. A big reason why censorship is often ineffective; banning information only increases its appeal, leading to a Streisand Effect in which the info becomes shared even more widely.

@G_S_Bhogal

This part is left off the page, with a dot dot dot.

These kind of stories annoy some readers. Because here’s what you need to do next. Read the thing again. This time you’re not reading for plot but for symbolism. You’ll likely find an answer that way.

To that end…

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

What do you think happened next?

I believe Flegg fell to his death. From the text, the main supporting evidence is this: When he understood his friends are not on his side, he learned that he has no friends. He was totally, terribly alone. This would have taken its toll on his mental fortitude. That is one awful discovery to make, even while stood firmly on solid ground. I believe Flegg’s physiology would’ve ‘let him down’.

That phrase. ‘Let down’. It’s idiomatic, sure, but in my opinion Flegg’s emotional ‘let down’ prefigures a literal fall.

Ah yes. There’s also the mention of ‘Jacob’s Ladder‘. Look that one up to understand the connection between ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ and death.

RESONANCE

Not gonna lie. The paragraph introducing the girls makes me squirm. As usual, the narrator gives readers a run down of a girl’s physical beauty (or otherwise). The boys are not described at all. Boys remain free of scrutiny. Women and girls get mighty sick of the constant, interminable objectification, not just in stories but in life.

Which leads to the question: Is it possible for an author to depict toxic ideas (e.g. toxic forms of masculinity) without showing them first on the page? By the end of this story, the author has critiqued boy culture. The girls appear empathetic in comparison to the unfeeling boys.

As for the ableism, the word ‘cripple’ has been reclaimed by the disabled community, but its casual use rankles. Can we excuse its use in a story written more than half a century earlier? Can we excuse a story for using a word which characters themselves would use (making use of close focalisation)?

These are questions likely to come up when reading a story with adolescents today. And I do think this is a resonant story. If you read this when you’re young, you’re going to remember it.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

For another resonant scene of falling, see the opening to Ian McEwan’s 1997 Enduring Love. This time, however, the characters are adults, and the perspective is from that of an observer as a man falls to his death from a hot air balloon.

The belief that walking under a ladder is bad luck comes from Ancient Egypt. A ladder leaning against a wall forms a triangle. This is a sacred shape because it represents the trinity of the gods. Passing through the triangle would desecrate them.

FEAR OF HEIGHTS

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Eva Holland, the author of “Nerve: Adventures in the Science of Fear.” They talk about her experience navigating the waters of cognitive-behavioral therapy to face her crippling fear of heights, all while exposing some of her deepest vulnerabilities.

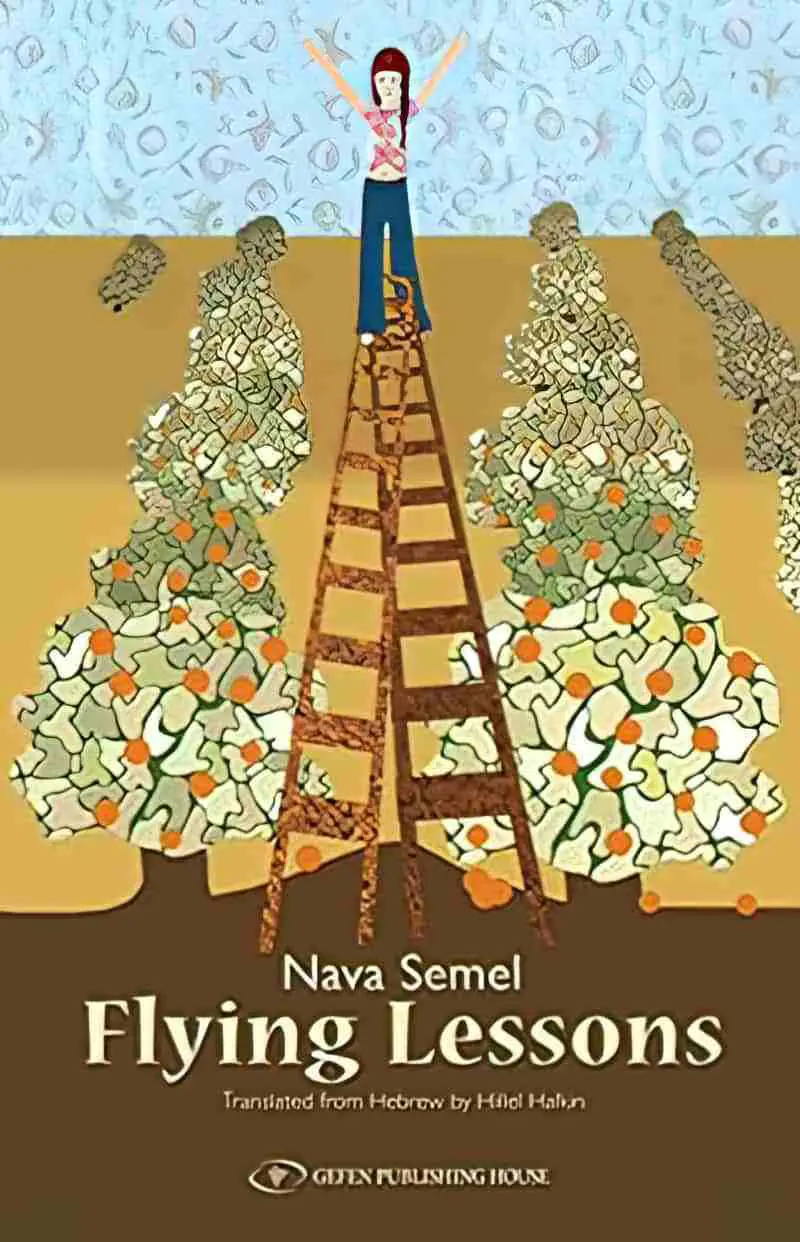

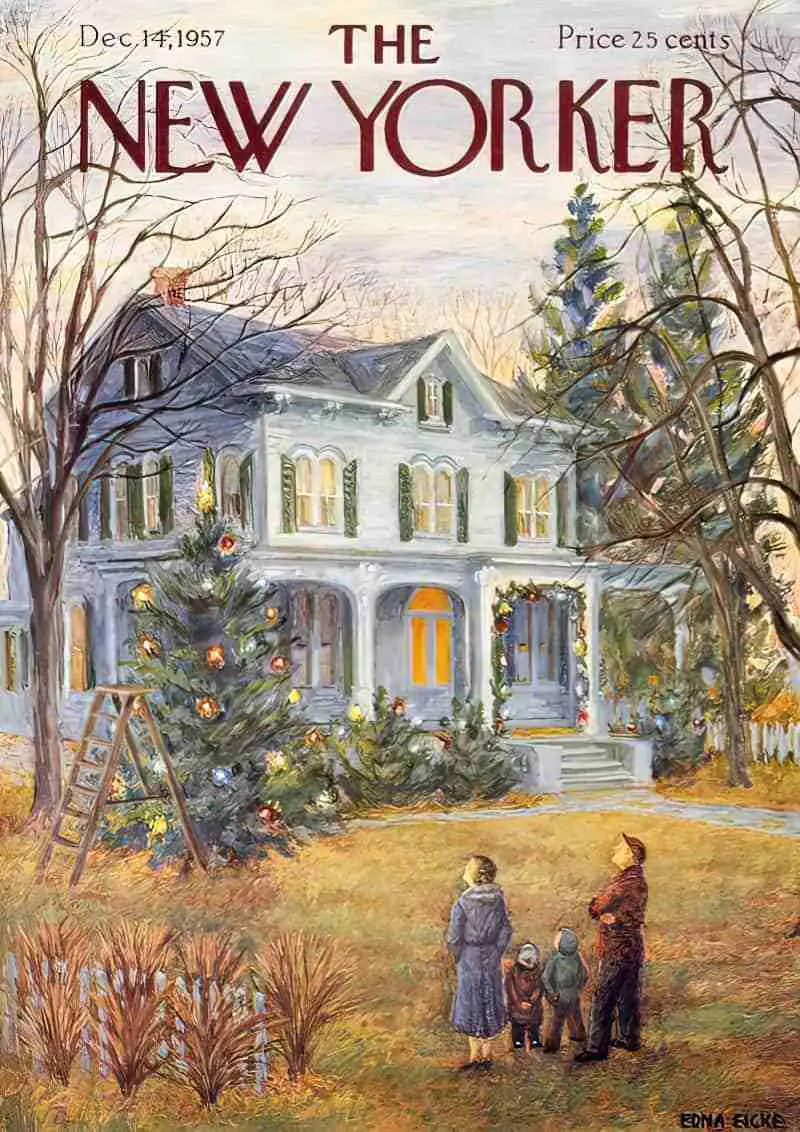

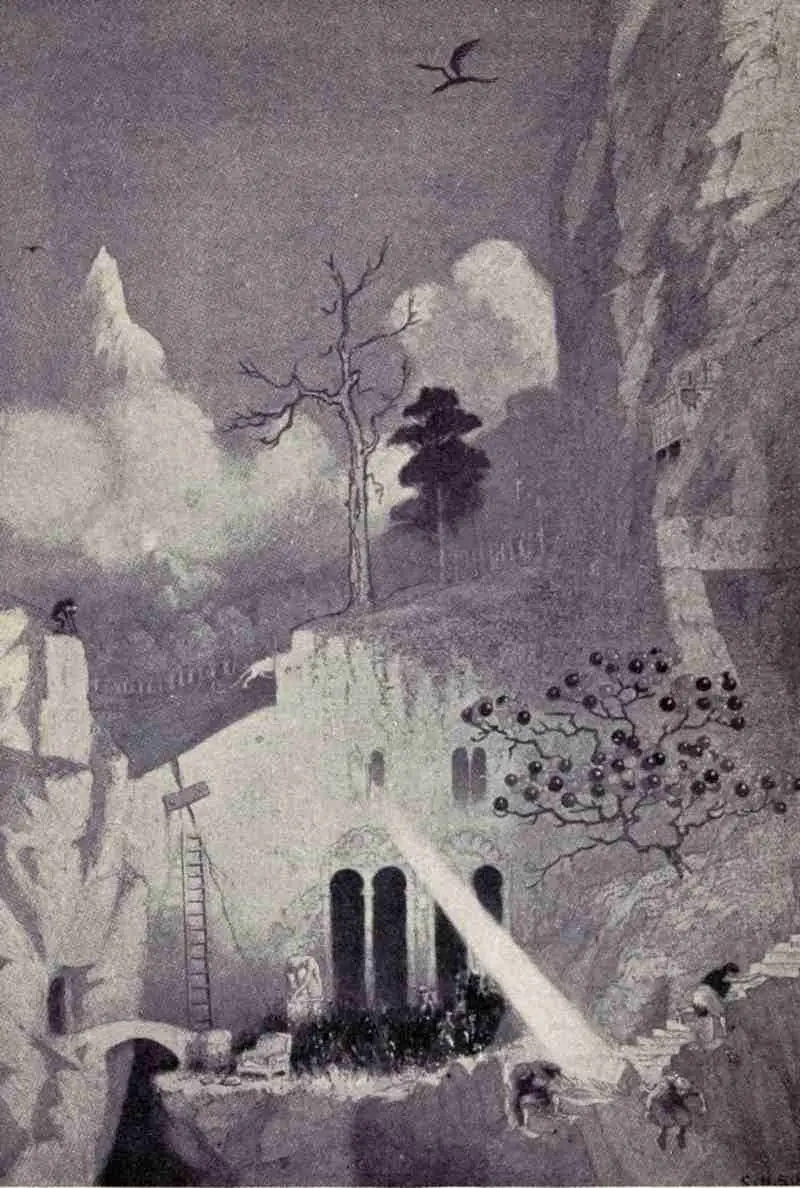

LADDERS IN ART AND ILLUSTRATION

Some ladders aren’t ladders.

A ladder is especially necessary if you are a miniature person.

Header illustration: ‘Seasons – Fall, Winter’ Illustrator not found c1890, but found in an Italian publication. German influence likely. Autumn, associated with apples, are frequently associated with ladders.