**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

What was your first paid job? At sixteen-years-old I worked as a checkout operator and was rarely given reprieve from the checkout (a ten minute break every three and a half hours). Although I worked there for a year and a half, the experience gave me no particular insight into the adult world, though I did conclude that about one in ten members of the public are seriously unhinged (either high on something, stressed to the max, or else some kind of Machiavellian combo in which a sixteen-year-old jammed behind a cash register makes for an easy target).

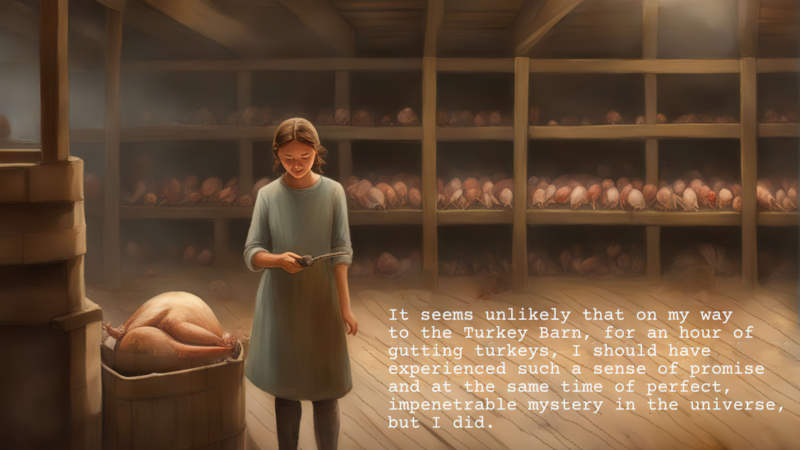

The shy 14-year-old narrator of Alice Munro’s “The Turkey Season” had a rather different experience at her first proper part-time job. As a Christmas season turkey gutter, she was treated as an equal among the gutters and pluckers. Looking back on this experience as an older woman, her interpretation of events has changed, not just because time has passed but because the culture itself has changed.

CONTENT NOTE

If you have not yet read the story (because you prefer to read analysis first), here’s your content note, via a post on social media which I happened across:

I have been enjoying the short stories of Alice Munro (all except for “The Turkey Season”, in which the cruelty to the turkeys overrides any interest in the fates of the human characters – but perhaps that is the point). In fact, Munro is especially good at representations of human cruelty, and sometimes the perpetrators meet a satisfying come-uppance.

Facebook

WHERE TO READ “THE TURKEY SEASON”

“The Turkey Season” was first published in the December 29, 1980 edition of The New Yorker. Find it also in Munro’s 1982 The Moons of Jupiter collection.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

NARRATOR

Like Del Jordan of Lives of Girls and Women, and like high school aged Alice Munro herself, this narrator is a Clever Girl. When the owner of the Turkey Barn asks if she’s educated, she knows the answer to the science question. She is keen to prove her father wrong about being too cack-handed to work at the Turkey Barn which is why she’s there. She has mental fortitude, and a Protestant work ethic. Work, to her, means doing things you don’t want to do, and she really does not want to be gutting turkeys.

If I had not had Herb to show me, I don’t think I could have learned turkey gutting at all. I was clumsy with my hands and had been shamed for it so often that the least show of impatience on the part of the person instructing me could have brought on a dithering paralysis. I could not stand to be watched by anyone but Herb. […] I couldn’t stand to be watched by Lily and Marjorie.

“The Turkey Season”

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SOCIAL ANXIETY AND THE FEAR OF BEING VISIBLE

Omg omg omg. It all makes so much more sense when you realise it’s not social anxiety but a fear of bring perceived.

Why do you feel more comfortable with a long coat and a mask as opposed to summer clothes?

Why do you DESPISE taking pictures? Especially if it’s someone else and not you taking them.

Why do you feel like you have to stop doing whatever it was you were doing when someone passes by?

Why don’t you want to tell anyone how leisurely you go about your day, taking a nap, going for a snack, sitting on your phone playing games etc. because you know they will comment on it and even though it’s not negative or mockery it’s still feels like you’ve been perceived?

Why can’t you make eye contact? Why can you do it only if the other person is looking away but the second when they look at you you stop listening and when you’re the one speaking you can’t bear to look at them because you know their eyes are on you and they are perceiving you?

Why don’t you want to dress excessively or wear nicer clothes? Because you will stand out

People mistake you for shy because you don’t speak often, but it’s really the fear of drawing attention to yourself more than it is the things you actually say, isn’t it?

Why do you hate overpopulated areas even when no one is speaking? BUT you still feel more comfortable when more than one person is in the room (but not too many!) so that the burden of being perceived is directed on someone else and you can safely lay back just observing the scene.

It’s all a defence mechanism

vroomvroomwee on Tumblr

It’s common to experience this particular fear as you change from a child into an adult. But like the poster above, I too think it’s worth making a distinction between social anxiety and the fear of visibility.

Alice Munro is extending a symbol web here. What other kinds of invisibilities exist in this milieu? Who else is afraid to be seen?

LILY

Workers are divided into a simple binary of turkey gutters and pluckers. Lily is a gutter.

Lily is middle-aged, rough-speaking in a way that the narrator hasn’t ever seen before in a woman, being of a different class.

The gutter/plucker binary is real, but I find it interesting that the workers are divided into two neat categories given that when it comes to sex and gender, too, people prefer neat containers, and it’s always two. “You’re either a man or a woman. Taken or available.” There’s no room in this 1940s setting for nuance (e.g. bisexuality).

MARJORIE

Lily’s middle-aged sister. Also a gutter. The pair of them are competitive gutters.

They sang at their work and talked abusively and intimately to the turkey carcasses.

“The Turkey Season” (Munro is expert at lining up unexpected adjectives and adverbs.)

Her husband is now disabled due to a rolled tractor accident and now she’s the boss of the house, and an abusive caregiver in turn. This couple is hardly an advertisement for heterosexual marriage. Shortly after her wedding day Lily considered drinking ‘Paris green’, a beautiful emerald coloured arsenic-based organic pigment made of copper(II) acetate and arsenic trioxide. This sort of thing was once widely available over the counter. Paris green was used for its pigment in green paint and was also used as a rodent poison, insecticide and fungicide. It was dangerous stuff:

Before electricity, coal fires were used for heat and light; these produced hydrogen gas, which when combined with arsenic which was present in “Paris green” of wallpaper formed toxic gas, arsine. A fungus Scopulariopsis breviculis present in damp wallpaper also metabolized the arsenic in Paris green to arsine.

Science Direct

The young narrator finds it a huge contradiction that these women are so good at this dirty job, that they could have been good at so many other (middle-class coded) jobs requiring equal if not lesser manual dexterity, and yet their thinking is so ‘slapdash, clumsy and infuriating’.

The reader might fill in that blank: It’s not a contradiction at all. It’s their class, evinced by their drinking and swearing, which keeps them in this lower-class, in this dead-end job gutting turkeys. They also have bad teeth. Another social marker. One thing follows the other, no contradiction at all. Social mobility is very difficult. Likewise, there’s no contradiction in their poor assessment of Irene, a younger version of themselves. These women despise their younger selves, and are victims of trauma. This is how they process things. Lateral violence. That’s how it works.

LILY AND MARJORIE’S FATHER

This cruel man does not appear ‘on stage’, but is there as a ‘ghost character’ — out of the story but important to the plot or theme. In this case, Alice Munro is showcasing various types of masculinity. This man is an old-school abuser who would threaten to hang his daughters if they didn’t comply. He even had a noose in the woodshed and would come very close to letting them hang in it.

He then married Marjorie off to one of his pals when she was sixteen because he wanted to be sure his daughter ‘would not get into trouble’.

Similar cruelties were dished out by the men in my own family, if I go back as far as that generation. These really were very cruel times. Violence was meted out as a parenting tool. But it took a few generations to change. Both Lily and Marjorie have failed to break the cycle of abuse regarding their own sons. (Neither has daughters.)

Cultures are still wrestling with the idea that children belong to the parents, the ideology at the heart of the so-called “Parental Rights Movement”.

The parent does not have an absolute right to control a child. Rather, the child has a right to the parent’s guidance and support, and the parent has a duty to offer that guidance and support.

“I OWN MY CHILDREN”: THE PARENTAL RIGHTS MOVEMENT AND HOW TO CHALLENGE IT“

These are the tools you need to understand where the “parental rights” movement comes from, what its goals are, and what you can do to challenge it. From AntiHate.ca

October 4, 2023

IRENE

A plucker. Irene is shown to have some emotional intelligence because one day in the toilets she saves the young narrator from an intrusive question from Gladys.

Irene is only about sixteen at the time, already married, already pregnant. She could be a younger version of Marjorie, who was also married off at sixteen. She has long red hair, which in a working class girl would mark her out as a harlot, undeserving.

Marjorie and Lily despise Irene for her so-called loose morals. The young narrator understands that Marjorie and Lily are not above Irene themselves as hard drinkers and swearers, but is not in a position to do so.

HENRY STREETS

An elderly plucker who works with Irene.

There was nothing remarkable about him except that he was eighty-six years old and still, as he said of himself, a devil for work. He had whisky in his thermos, and drank it from time to time through the day.

“The Turkey Season”

A man this age in the 1940s was born in the 1860s, during the American Civil War, The New Zealand Wars, The Bhutan War. This guy really is a link to a much earlier time. (As a kid, who was the oldest person you ever met? As a child of the 1980s, I have memories of very old people who had been born in the 1800s.)

Henry is a friend of the narrator’s family and suggested (part joking) that the narrator should come work as a gutter.

HERB ABBOTT

The foreman at the Turkey Barn who attracts attention due to his illegibility.

Tall, firm, plump with thinning dark hair ‘combed straight back from a widow’s peak, and his eyes seemed to be slightly slanted, so that he looked like a pale Chinese or like pictures of the Devil, except that he was smooth-faced and benign.’

Works on boats in the off-season. Has quick, economical movements when he works, which shows how closely the young narrator is watching his every move. Lives above the poolroom on the main street.

MORGAN ELLIOTT

Owner and boss of the Turkey Barn.

Treats his son roughly.

MORGY ELLIOTT

Morgan’s son. Kills the turkeys with his father. Goes to the same school as the narrator, where the narrator considers him ‘stupid and despicable’. At school she is smarter. But at her job at the Turkey Barn, Morgy Elliott is weirdly above her in the hierarchy, as boss’s son.

GLADYS

Morgan Elliott’s sister. Works slowly, goes home if she isn’t feeling well. She is a little friendly to the narrator though not to Marjorie and Irene. Worked as a bank teller in Toronto for years before returning to the small Ontario town where this story is set.

Rumour has it that Gladys suffered a nervous breakdown and came home to live with Morgan and be cared for by his family. Later in the story she tells the narrator that her periods are ‘profuse and painful’ — a taboo subject back then. I suspect Gladys suffered from endometriosis or similar. Her ‘breakdown’ may have come from the epistemic injustice of not being believed whenever she tried to tell people how much pain she was in. In fact, the ‘breakdown’ may be the painful episodes themselves. Each of my grandmothers was said to have suffered a ‘nervous breakdown’, which was the name given to all manner of ailments, especially relating to women. I wonder what we would call such events today. In one grandmother I suspect postpartum depression, due to its timing. She’d ‘had to get married’, as people euphemistically put it in those days, and was brought up in the Catholic tradition, later rejecting it. The other grandmother had a ‘nervous breakdown’ between her first husband dying of cancer and her marriage to the second husband. The stress of being an unmarried woman was too much for a woman who townspeople had considered ‘a lady’, yet now she was seeing a butcher.

That said, Gladys is depicted as a bit of a hypochondriac. Aside from her menstruation issues, Gladys talks about her sensitive scalp, her cracked and red hands, how she can’t use ordinary soap. This woman sounds to me like someone who has been medically gaslit her entire life, and is looking for someone — anyone — to give her some understanding. Failing that, a random 14-year-old who, only by circumstances, is obliged to listen.

Lily and Marjorie start a rumour that Gladys is interested romantically in the foreman, Herb Abbott.

Gladys is thorough but not fast at turkey gutting. Not as old as Lily and Marjorie, but old in the eyes of the young narrator. Over thirty. She wears make-up which doesn’t match her skin tone. Puts her hair in rollers because her skin is too sensitive for the chemicals of a permanent.

She seemed offended by everything that went on and had the air of keeping plenty of bitter judgments to herself.

“The Turkey Season” (Don’t you just know exactly what that looks like in a person?)

Across various stories, Alice Munro broaches what is lately called “aesthetic labour” required of women, which can transform into excessive care of one’s house once looks wane (“Wigtime“, “Winter Wind“). In this story Munro makes an interesting distinction between what modern feminists might say is “choice” versus “obligation” around personal up-keep, and also makes the link between feminine work on the body and work on the house:

There are different ways women have of talking about their looks. Some women make it clear that what they do to keep themselves up is for the sake of sex, for men. Others, like Gladys, make the job out to be a kind of house-keeping, whose very difficulties they pride themselves on.

“The Turkey Season”

BRIAN

The new guy who shifts the story from iterative to singulative. “Every day at the Turkey Barn… [iterative]. Then one day… [singulative].”

He’s mean.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE TURKEY SEASON”

Alice Munro’s narrator introduces the characters at her seasonal job at the Turkey Barn via a series of character sketches with the nuance of someone literary, smart and thoughtful (indistinguishable from the author herself). However, there are things she didn’t understand about her co-workers which she has come to understand now that she is older, filling in some gaps.

This story is set in the real town of Logan, on the hock of a dog-leg about equidistant between Goderich and London (both of significance to the author).

“THE GLASS CLOSET”

“The Turkey Season” shows what it was like to be queer in the late 1940s. There’s a phrase “in the glass closet”, meaning a person is so visibly queer they cannot possibly hide it, yet they are not out. This person may not even be out to themselves, because they don’t have the words to describe themselves, let alone community.

I’m not a fan of this phrase because it flattens the complexity of what it means to be visibly and legibly queer. When I say ‘flattens’, I mean any man who presents effeminately is labelled gay (even if he’s straight, or asexual, or bisexual, or Autistic, or disabled, or speaks with an impediment…). Any woman who presents butch is labelled lesbian (even if she’s straight…). This is a nuanced take, because although gaydar is a thing, I don’t believe it’s possible to look at someone and know how their attraction works. To say someone is ‘in the glass closet’ is an example of a thought-terminating cliché. Edward Gorey’s biographer uses this phrase to describe his subject, and concludes Gorey must have been gay. While doing this, he ignores all other possibilities, including the most likely: That Gorey was asexual.

I quivered in curious expectation, as Lily and Marjorie did. We all wanted to see the flicker of sexuality in him, hear it in his voice, not because we thought it would make him see more like other men but because we knew that with him it would be entirely different. He was kinder and more patient than most women, and as stern and remote, in some ways, as any man. We wanted to see how he could be moved.

“A Turkey Season”

Munro’s narrator is more overt and pedagogical than most of the author’s other narrators. She is teaching a 1980s audience something about how it was to be queer a generation earlier.

The author handles it with nuance, I think. This snapshot of characters working at the Turkey Barn conveys the issues of identity labelling.

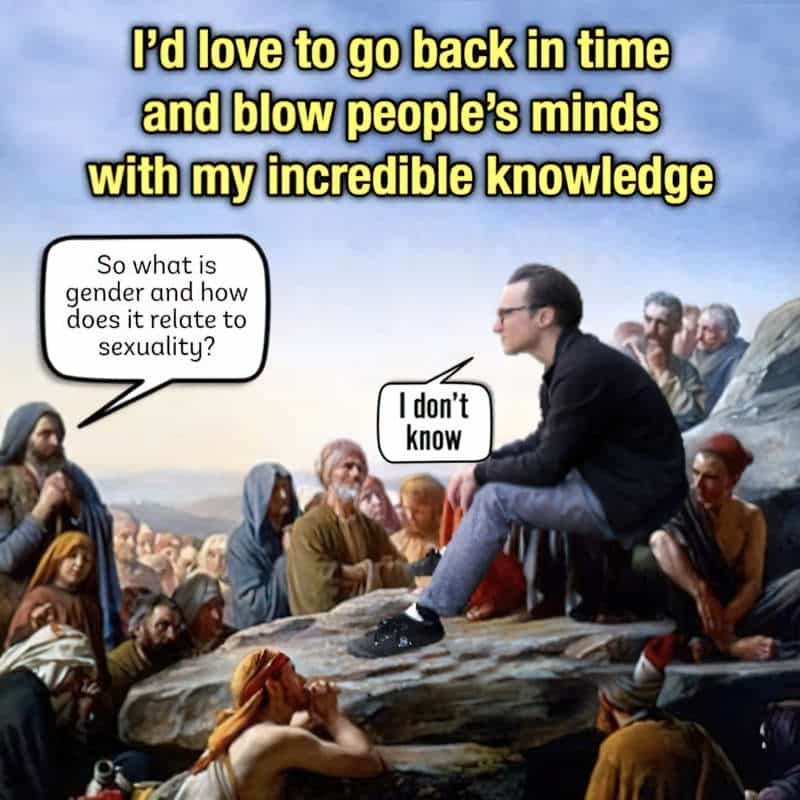

In the 1940s there was no distinction between sex and gender, let alone gender identity, gender role and sexual attraction:

They really seemed to believe–the women did–that it was the penchant for baking or music that was the determining factor, and that it was the activity that made the man what he was, not any other detours he might take, or wish to take. A wish to play the violin would be taken as more a deviation from manliness than would a wish to shun women. Indeed, the idea was that any manly man would wish to shun women but most of them were caught off guard, and for good.

“The Turkey Season”

Come the 1980s, more people understood what it meant to be gay. But increasing visibility has its upsides and its downsides. Munro is careful to limit her summary of gay attitudes to women (–“the women did”–). She exemplifies how Nice White Ladies (TM), and also hard-living working class women of the 1940s limited their imaginative scope when it came to sex. By the 1980s, the gay movement was marketing “love is love”, emphasising the love aspect of gayness to the straights. There was a reason for this. Gay people everywhere have always had to fight hard to get the sexual aspects of their identities accepted. The fight is ongoing.

In the 2020s, different letters in the LGBTQIA+ acronym are still fighting to be accepted. Bisexuals and asexuals are still fighting against invisibility. Trans and genderqueer communities are stuck with the never-ending fight against the widespread conflation of gender identity and sexuality. (An unintended consequence of shoving both orientation and gender identity labels into the same acronym, partly.)

HERB’S MYSTERIOUS MASCULINITY

The narrator remembers Herb the foreman as a man cloaked in some kind of mystery. As a 14-year-old, the narrator fancied Herb herself. It is only looking back, when she has the queer literacy of the early 1980s, that she realises he was probably gay.

That said, this 1980s narrator refuses to speculate about whether Herb was homosexual or not. In the early 80s, to speculate on someone’s sex life was very much still taboo. (It still is, for many of us who were around back then.) Unfortunately, the taboo around sexual orientation only applied to non-straight orientations, and evinces a sense of shame applied only to non-straight orientations. This is what I call toxic taboo — it would be a mistake to think it is borne of etiquette and ‘minding one’s own business’.

Lily and Marjorie were street smart compared to the young narrator, but there was a hard limit to their emotional literacy. Taking a prurient interest in Herb’s sexuality, they took any opportunity to think about it. Noticing how the young narrator had a thing for Herb, they teased her about liking him.

Marjorie and Lily talked about marriage. They did not have much good to say about it, in spite of their feeling that it was a state nobody should be allowed to stay out of.

“The Turkey Season” — a beautiful sentence illuminating the compulsory obligation of marriage

Munro elucidates beautifully the fairly common phenomenon in which adolescent and young teenage heterosexual girls can be romantically interested in gay boys and men. It’s not just because the gay boys are ‘safe’, meaning a safe target due to their permanent lack of reciprocal interest (not always true, but that’s the idea). No, Munro goes further than that, and describes how a young woman might be (inadvertently) smitten with a gay man because the masculinity of a gay man ignores women entirely, in contrast to hegemonic (fragile) masculinity, which is too often predicated entirely upon distancing masculinity from femininity:

He aroused this feeling by being circumspect and not making the jokes some men did, and at the same time by not being squeamish or gentlemanly. Some men, showing me the testicles from the turkey, would have acted as if the very existence of testicles were somehow a bad joke on me, something a girl could be taunted about; another sort of man would have been embarrassed and would have thought he had to protect me from embarrassment. A man who didn’t seem to feel one way or the other was an oddity–as much to older women, probably, as to me.

“The Turkey Season”

THE PROBLEM OF ILLEGIBLE MASCULINITY AND PRURIENCE

To use less poetic wording, Alice Munro has described two different types of hegemonic masculinity:

- the overtly misogynistic, taunting kind

- the benevolently sexist kind

Both types of men are already familiar to the 14-year-old girl narrator. The gay man evinces another kind of masculinity which is far more gentle and attractive for being neither of these. However, Herb’s queerness is not legible to any of these women in this era (the late forties). Even the rough-talking middle-aged gutters who would pride themselves on being down-to-earth about sex and childbirth and what-have-you are baffled and thereby intrigued.

Eventually, the mystery of Herb all comes to a head when the young narrator is witness to another adult conflict she does not fully understand at the time.

BRIAN THE NEW GUTTER

In the lead up to Christmas, the Turkey Barn gets a new gutter. Brian is in his late teens and very handsome. Perhaps a relative of Herb. They worked on a lake boat together last summer. In any case, he is staying with Herb over the poolroom.

However, the others don’t like Brian due to his crudeness. No one complains to Morgan (the owner) about Brian, though, not even Gladys, who bears the brunt of his bullying.

After a while he seemed just like somebody with a bad case of hiccups–his insistent sexuality was that monotonous and meaningless.

“The Turkey Season”

Lily and Marjorie protect the narrator from his advances, but he especially likes to bully Gladys. She deals with this by retreating into the bathroom, but can’t do that and also earn her pay.

The young narrator can’t understand why Gladys doesn’t complain to her brother, who is the boss. But she doesn’t. Looking back, she can’t understand why none of them complained to him.

WHY DOES NO ONE SAY ANYTHING?

I’ve had a few epiphanies like that myself in the post #MeToo era. Why did everyone think it was okay to install a security camera in the women’s locker area at the supermarket where I worked, which was also the same place where teenage girls had to get changed after coming in to work for the after school shift? I never got changed there, fearing that camera. Instead, I had to wear my bottle-green Pak n’ Save smock while riding my bike to and fro — an uncomfortable garment which then needed to be laundered and ironed at my own house rather than me just throwing it in to be laundered by the dedicated washing woman. I could have got changed in a toilet cubicle like some of the girls did, but I didn’t feel safe getting changed in that place at all.

One day I heard the widely disliked male assistant manager speaking lewdly about a particularly good-looking young co-worker who had just left to take up a job at the pizza restaurant. It was then that I understood what I had always suspected: That he was in the habit of leering at the security cam in the women’s changing area whenever certain teenage girls came in. He had access to everyone’s shifts. This disturbed me greatly.

Did I say anything to anyone? To him? No. The power imbalance was too great. I figured if I knew, everyone knew. It must be just me who was offended by it, and too prudish to get changed in a fluorescently-lit room opening onto a high-traffic corridor with a very obvious security camera installed in a high corner. Besides, this man widely put it about that “check-out chicks were stupid”. No one would have taken me seriously. My main regret is not getting out of there sooner. They paid double at McDonalds across the carpark.

THE CLIMAX OF THE TURKEY SEASON

It’s the last day of school before Christmas. The narrator of “The Turkey Season” gets an early mark from school. She goes to the Turkey Barn, and is surprised to find no one working. However, someone is yelling their head off.

It’s Morgan, the shouty boss, yelling at Brian. Something something “perv3rt”, something something “filthy”. Morgan also tells Brian he has to get out of town that same day.

Brian does as he’s told. The narrator hears that Gladys is ‘recovering’, but no one ever tells the narrator what happened, probably thinking her too young for such details. The narrator assumes he assaulted Gladys.

THE VISIBILITY TRAP

One of the things I admire the most about Alice Munro is her ability to make use of symbolism and metaphor at a level which is barely perceptible to the reader. Oftentimes I’ll do a close-read of an Alice Munro short story and then several days later I’ll realise something else she was doing.

It took me another few days to work this out, but remember how Herb was left out of the photo? On the surface level of the story, that’s because someone needed to take the photo, and that person was Herb. At a metaphorical level of the story, Herb is not in the photo because in some ways he remains illegible and invisible to the narrator. In other ways she knows exactly who he is, and she is sure to tell us that she doesn’t need a photo to remember him by. His image is so clear in her memory.

These days, the queer community talks about the so-called ‘Visibility Trap’.

There are many ways to engage in visibility politics. But we have to be aware that visibility can sometimes have its drawbacks or be dangerous. There’s a lot of discussion now in trans discourse about the trap of visibility. Visibility can lead to folks advocating against. This is something I don’t have an answer for, but there is a power in making yourself invisible. This goes back to the fifties, the homophile movement, their interest in respectability and saying, “We’re just like you! We’re just gay!” But there have been many different ways LGBTQ people have advocated for visibility across the 20th century — longer than that.

Margaret Galvan, author of In Visible Archives: Queer and Feminist Visual Culture in the 1980s,

To give a very real example of this, Torrey Peters, author of the bestseller Detransition, Baby (which I love), wrote transgender literature for years before realising that she might as well just write for herself and her friends because the publishing industry wasn’t genuinely interested in promoting trans voices. Until suddenly they were. In an interview I remember her talking about the day she went to her transgender writing group. Caitlin Jenner had just come out as trans. Peters describes the pall of anxiety which settled upon them all. Someone pointed out that everything would change now. A whole lot of crap was coming their way. And they were right. (The double-edged sword? Suddenly the publishing industry became interested in publishing trans literature.)

Another example of the visibility trap: With increasing visibility the aspec (asexual and aromantic) community is now subject to much of the same bigotry as the trans community, including the allegation that there’s no such thing as asexuality, only asexuality as a cover for p*dophilia. (The very same doctor promoting this misinformation is a longterm and notorious trans bigot as well.)

However, we are now at a part of history in which individuals often feel obliged to disclose every aspect of their sexuality (orientation, attraction and also gender identity) before people feel they can ‘know’ and ‘trust’ them sufficiently to do a good job, or be a good friend, or even be a reliable and trustworthy work colleague. Individuals who work in creative fields are especially targeted.

THE NARRATOR’S GRADUAL EPIPHANY

Years later, the narrator remembers Herb’s look of shame at the time, and concludes Brian had been caught having sex with Herb that day.

Prompted by a photo which she has kept all these years, she describes her evolution in thinking. If you’d like to know how to write an ekphrastic photograph scene in fiction and do it well, the ending to “The Turkey Season” makes for an excellent model.

The older narrator now understands that Lily and Marjorie never really thought that Gladys and Herb would get together. They just thought ‘single people ought to be teased and embarrassed whenever possible’. For a long while she assumed Herb was having sex with the young man but she has since pulled back on that, content now to accept that she will never know. If you like, this epiphany was “the last part of the turkey to cook”.

THE TURKEY METAPHOR

It seems logical to me that women writers who spend much of their lives doing housework and cooking and preparing the traditional celebrations will come up with different literary symbolism from male counterparts. Alice Munro, as a home cook, would understand that turkeys take a long time to cook, and different parts of the turkey cook sooner than other parts. So for me the turkey is a metaphor comparing cooking speed to processing something unknown over decades and still not being certain your ideas are ‘fully cooked’.

I may be drawing a long bow with the turkey metaphor. Either way, Alice Munro seems to be teaching readers something here: We must all learn to sit with not knowing the details of other people’s private lives, however curious we are, however driven we are to understand the workings of other people’s sexualities.

This lack of knowing is symbolised by the maimed turkeys the workers are gifted for Christmas. These turkeys cannot be sold at full price, but the boss tells everyone that the maimed turkeys sometimes offer the tastiest meat.

Similarly, sometimes we’re all better off when we don’t know the full story. Cf. the storytelling technique of mystery boxing, or the ancient art tradition of leaving part of an interesting something out of frame.

As ever, Munro asks us to hold two contradictory ideas at the same time:

- Other people’s sex lives are none of our business.

- When we can’t get a grip on other people’s sex lives, this is the very thing that makes us really want to know more.

FURTHER READING

Alice Munro shows great empathy for people who are not romantically inclined. In this story she describes the prurient interest people take in the sex lives of the long-term single ‘a voluptuous curiosity’.

Her story “A Real Life” is a great example, and she gives the ‘chronically single’ woman in that story the last laugh while illuminating the ridiculousness of what has more recently been called compulsory sexuality.

RESISTING LABELING

In “The Turkey Season”, Alice Munro seems to fall on the side of, “nobody needs to know your identity labels”. Readers never know for sure if Herb and Brian even used labels to describe themselves, and the narrator ultimately resists labelling them in hindsight, even with access to the words.

The queer community continues to discuss the question of ‘How many distinct labels are actually helpful?’

Philosopher Alyson Escalante wrote about ‘the proliferation of identity’ and gender nihilism. Writers such as Kravitz M. have responded:

Continuously breaking labels down and creating terminology for each facet of one’s identity shrinks communities until it’s just one person convinced that they’re the only one who relates to their experiences. It isolates people and ignores the importance of individuality within a collective identity.

On Hyperpersonalized Sexual Identity

EMBRACING SOME FORMS OF LABELLING

Sometimes I think about microlabels vs macro(??)labels. About how I think people should have both, as they are valuable in different aspects of life.

Macrolabels are stuff like queer, lgbt+, bisexual, lesbian, trans, etc. They can mean wildly different things to different people, and two people with the same macrolabel can express it in massively different ways.

Macrolabels are for community. For solidarity. For planting your flag in the ground going “this is me, this is us, I belong with them and they belong with me”. A united front against the oft-terrible other, common ground in others. Macrolabels are what we need for introductions for those Not In The Know, for political rallies, for group meets.

Microlabels are for individuals. They’re for finding those conjunction of words that just fit you perfectly isn’t that amazing? For knowing yourself thoroughly and specifically, for letting others know how you feel and how you view the world on a deep level. These aren’t for introductions, these are for conversations. These are more intimate, more unique. These are not labels to rally behind as banners to show solidarity, but to keep close to heart, and warm in your heat. As valuable as macrolabels in my opinion, but for different reasons.

nymph1e

OTHER SHORT STORIES IN THE MOONS OF JUPITER (1982)

In case you have access to The New Yorker archives, five of the Moons of Jupiter stories were published in The New Yorker between 1978 and 1981.

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings I: The Connection“

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings II: The Stone in the Field“

- “Dulse” also in the July 21, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Turkey Season” also in the December 29, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “Accident“

- “Bardon Bus“

- “Prue” also in the March 30, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Labor Day Dinner” also in the September 28, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd“

- “Hard-Luck Stories“

- “Visitors“

- “The Moons of Jupiter” also in the May 22, 1978 edition of The New Yorker

This time of year, turkey gets a lot of attention. But let’s be real, turkey is massively overrated. It’s dry. It’s flavorless. And cooking it wrong can burn down your house.

Enter: ham, the oft-forgot holiday centerpiece that packs a hardier punch when it comes to flavor, juiciness, and color.

The Most Delicious Holiday Meat Is A Miracle of Modern Science