**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Winter Wind” is a coming-of-age short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. Find it in Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You (1974).

As I read this Canadian narrative, here in Australia we are experiencing the hottest spring on record, with headlines such as:

- New overnight record temp set

- Fire ban in Queensland over record temps

- Qld braces for record temps

- fire danger; 2023 on track to be world’s hottest year on record

- temperatures exceed 1.5C above pre-industrial levels for first time

- East coast on storm alert with possible damaging winds, hail forecast, as near-record heat builds in West…

So a low-stakes 20th century story about a snow blizzard is as hygge as hygge gets right now. I don’t want summer. I want to sit at a table with my older female relatives, doing my high school homework by lamplight while outside a snow blizzard rages on.

Except, is this story that, though? Cosy and comfortable? Mmm…

“Winter Wind”, like other stories in Alice Munro’s Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You collection (notably “The Found Boat“), takes the reader on an unsettling arc as the emotional valence of the narrative changes from cosy to downright ominous.

Also like “The Found Boat”, this short story could (almost) be about Del Jordan from Lives of Girls and Women. It’s not Del, because Del Jordan during her high school years had moved in to town with her mother and a housemate, away from the family farm at the bum end of town.

But since it’s a pain to structure sentences when writing about unnamed characters, Im’ma call the girl in this story Del anyway. Note that Alice Munro hasn’t named her, though.

“WINTER WIND” AND THE FAIRY TALE TRADITION

Turns out I’m in the habit of linking Alice Munro short stories to classic fairy tales e.g. “The Red Shoes“, “The Little Mermaid“.

This time I move away from Hans Christian Andersen and into the German tradition. The Grimm Brothers took ominous pop culture tales for a general audience and repackaged them for children (a process known as ‘bowdlerisation’.)

I’m not suggesting that Alice Munro consciously wrote fractured fairy tales; rather, fairy tales speak to deeply held human fears using universal symbolism, and Munro does that also.

THE TALE OF A VULNERABLE GIRL AND HER TWO-SIDED GRANDMA

“Winter Wind” gives me “Little Red Riding Hood” vibes. Note that this European fairy tale, also known as “Little Red Cap”, was originally an oral tale told by and for women. It was only after the Grimm Brothers got hold of it that it became a patriarchal story about a man (the woodcutter) stepping in to save a vulnerable, naughty little girl from deserved death for daring to fail instructions.

Similarities between “Winter Wind” and “Little Red Riding Hood”:

- The main character is a young woman on the cusp of adulthood (though your childhood picture books may depict her as a much younger child)

- The young woman takes a trip to her grandmother’s house.

- But when she gets to the grandmother’s house there’s a kind of duplicity. In the fairy tale, the grandmother is not the grandmother (but the wolf). In “Winter Wind” the grandmother has a different kind of duplicate in the form of her sister (the main character’s great aunt).

- There’s also the spectre of the other older female relatives, who form a chronological chain leading into dementia and eventual death. (Both stories feature female death as inevitable backdrop.)

- The outdoors is considered dangerous for girls, and Red Riding Hood goes into the wild at her peril. In “Winter Wind”, the example of the woman who dies while milking her cow during a blizzard serves as reminder that nature is murderous. It’s no accident that the person who died is a woman, not a man (who we might consider either more hardy or more expendable as a necessary labourer, or both).

- In “Winter Wind” Munro takes the reader out of linear time by presenting us with an older woman looking back on her young life while contemplating other relatives who have already died. To make use of Greek terminology, this ‘timelessness’ is known as ‘mythos’ (in contrast to ‘chronos’) and is a feature of fairytale settings in general.

“WINTER WIND” IN A NUTSHELL

You know, I’ve decided to call this young woman Del, but we might also call her Alice.

The biographical relevance: Alice Munro, the author, herself took on the household tasks as a young woman when her own mother suffered from Parkinson’s disease.

Likewise, the young first person narrator of “Winter Wind” (okay, “Del”), is doing the same here. This is familiar psychological ground for Alice Munro, and “Winter Wind” is just one of numerous stories about caregiving across her corpus.

ALICE MUNRO’S FICTIONAL CAREGIVERS

- “The Peace of Utrecht“

- “Images“

- “Memorial”

- “The Ottawa Valley”

- “Winter Wind”

- “Spelling”

- “Friend of My Youth”

- “Wigtime“

- “Accident”

- “Chaddleleys and Flemings: Connection”

- “Family Furnishings”

- “Soon”

- “The Ticket”

BIOGRAPHICAL SETTING

Munro, like this narrator, lived just outside a rural town growing up (in Munro’s case, on a fox farm), while attending school. She visited relatives who lived in the town and also went to school in town.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “WINTER WIND” BY ALICE MUNRO

In “Winter Wind”, an older woman narrator looks back on her own high school years and remembers a particular day when she sought refuge from a blizzard at her grandmother and great aunt’s house rather than going all the way home after school was let out.

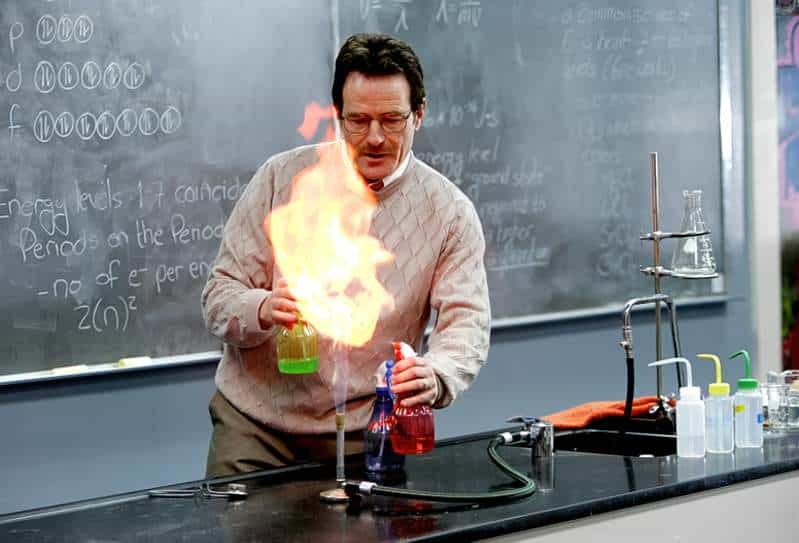

Significantly, Del is in a Chemistry lesson when the blizzard started up. If I’ve learnt anything from Breaking Bad, it’s the symbolic significance of chemical reactions and character change. (Like “Winter Wind”, Breaking Bad also goes from hygge to ominous — it’s right there in the title.)

Del’s elderly relatives’ house is a quiet, clean and cosy respite—a stark contrast against Del’s bustling, hectic home life, where this high school girl does the bulk of the household tasks due to her mother’s degenerative illness. She is often annoyed by the rest of the household, in which keeping the place anywhere near clean is a Sisyphean task.

At this time in her life Del is also frequently annoyed by her mother. They frequently argue, but I get the impression that they argue because it is safe to argue.

Today at her relatives’ house, Del does her homework at their kitchen table—a rare luxury. Normally she’d be doing housework, getting the dinner ready.

Using this visit as the framework for the story, this older woman narrator reflects on a generational chain of various other relatives. The reader can assume that, at time of writing, the other characters mentioned are dead and gone, so this is an older woman reflecting on her dead female relatives, making connections to herself, looking ahead to her own end-of-life as much as looking back on it. (Time folds in on itself, loses its linearity, à la fairytale time.)

The young narrator ends up spending several days with her relatives as the blizzard gets worse. Despite the cosiness of her extended relatives’ home, and their unwelcome (slightly judgey) offers to help with the housework at home, the young woman has a strong hankering to return to her own house, where she is free to be herself and do as she pleases, precisely because she takes care of the household.

This desire to leave this cosy but uncomfortable house even with a blizzard in progress upsets her grandmother and great aunt, ostensibly because someone they have heard a friend of theirs just died in the snow while out milking the cows, but there’s more to their desperation than that.

Now that the narrator is getting older herself, she can understand how the two old women might have felt: Generally ignored by everyone, thankful for the presence of youth, and saddened at how everyone who visits the old women seems to visit out of obligation. Visitors stay for as little time as possible and then can’t wait to leave.

Although the narrator had her reasons for wanting to leave that wintry day, and is fair to her teenage self*, she also seems to feel a sadness and a measure of guilt for wanting to scarper out of there when her grandmother and great aunt were doing their best to make her comfortable.

The sad reality: Because of their acculturation as women, the old ladies were always going to fail at making a (young, female) visitor feel welcome.

*Note that this is one of those Alice Munro stories in which an older woman is old, middle-aged and young all at the same time.

Inside, we are ageless and when we talk to ourselves, it’s the same age of the person we were talking to when we were little. It’s the body that is changing around that ageless center.

David Lynch

ANALYSIS OF “WINTER WIND”

This short story has me thinking about:

- Western notions of ‘the true self’ and the guilt we feel when we start to feel our socially differentiated ‘selves’ slipping (hence the connection with the duplicity in “Little Red Riding Hood”)

- Michelle Gelfand’s research around ‘loose’ and ‘tight’ societies (and contexts)

- A famous 1980 essay by feminist Marion Young about how female bodies are constricted in space

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE TRUE SELF

Readers crave certain things from stories. One thing we like to see: A differentiation between how a character acts around others, and who a character is in private.

In “Winter Wind” we see Del struggle to reconcile who she is expected to be at her grandmother’s house and who she is at her own house. She hasn’t yet realised that everyone has what Japanese people call an ‘omote’ (front) and an ‘ura’ (back).

(Modernist short story author Katherine Mansfield was also concerned with the difference between multiple selves. We know this from her diaries and fiction, especially in the short story “Prelude“, with the character of Beryl, and in the poem she called “The Gulf”.)

THE TRUE SELF AND THE WEST (WEIRD COUNTRIES)

Westerners aren’t taught to accept these different sides of ourselves. Children’s literature is full of plucky heroes and heroines in search of the ‘(one) true selves’. We urge our young people in various subtle and non-subtle ways to discover who we really are, then go for it. To take one modern example, an unexpected outcome of increasing LGBTQ acceptance is the pressure to disclose at an ever-decreasing age how your attraction and sexuality works. And keeping these things private is less and less acceptable, because everyone must be legible now, to be accepted.

When we convey to young people the idea of the ‘one true self’, it can be more difficult to accept difficult feelings as part of the natural ebb and flow of life:

In the West, we nurture the fantasy that a ‘healthy psychology’ requires a flowering of what we have decided to call ‘the true self’, or ‘true colours’, or ‘integrity’.

If you, too, have a concept of ‘the true self’ you probably come from a WEIRD culture (Western, educated, industrialised, Rich and Democratic). As evinced by the reality that Japanese language has words to describe different sides of oneself, non-Western countries around the world tend to be more accepting of how one is expected to act is different from who one is. Are you Chinese? You’re probably fine with the rule that you simply don’t say certain things at grandma’s house.

LOOSE AND TIGHT SOCIETIES

This cultural difference is probably connected to what Michelle Gelfand has termed ‘loose’ and ‘tight’ societies.

For more on this concept see: Individuality, The One True Self and Social Norms In Literature. Japan is a tight society. New York City is a loose society. The distinction depends on expected conformity, tolerance of difference. Tight societies were much quicker to adopt mask-wearing and social isolation measures during the 2020 phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, it’s more difficult to live as a minority identity in a tight society. Each type of culture has its pluses and minuses.

LOOSE AND TIGHT CONTEXTS

Contexts as well as countries sit on a spectrum between loose and tight. A university lounge is probably loose. A council library is probably tight (no food, no talking etc.).

In the case of “Winter Wind”, Del’s grandmother and great aunt’s house is a tight context. The teenager is required to do much of what psychologists call ‘self-monitoring’. There’s even a barrier between herself and the table: To avoid damaging the wood, Del is required to do her homework on top of a protective barrier of newspaper. Her grandmother’s house is cosy, but it is not comfortable. Del must be on her best behaviour. This is tiring, and she knows she can’t keep her best self on display forever. That’s why she’s desperate to return home, even in a blizzard.

When Del is at home, she is comfortable. for all the hard-work she’s required to do there (due to her mother’s illness), the beneficial trade-off is that Del is fully in control of her environment, which is ‘loose’. Nothing can ever be perfect at home, due to illness, a big messy family and Del’s time constraints.

ALICE MUNRO AND HOUSEWORK

Housework is most often construed as a burden on women and girls, but Alice Munro has recapitulated it in this story as a type of freedom. To be fully at home in your own house is a freedom that not everybody enjoys.

Now I remember something Alice Munro has said in interview: Until moving to be near her daughters as an older woman, Munro spent her entire life taking responsibility for households. But even as a teenager doing all the housework, she didn’t resent it. As an adult and a writer, Munro utilised housework time to dive deep in her own thoughts. A low-stress, low-brainpower job can be an ideal occupation for a career author.

Q: So, if cleanliness is next to godliness, and women spend so much of their time furiously trying to get rid of dust, the vacuum cleaner must have seemed a very good idea.

A: If only it had. Of course vacuum cleaning cuts down the amount of actual physical sweeping time people had to [do]. The problem was the standards of expected cleanliness rose to fill the time available. God forbid women might actually get some time to do other things with their day. Moral panic in the 1920s and 1930s as these technologies became available was pushing for standards of cleanliness to become more important. The expectation was to Hoover daily [with] elaborate cleaning routines [for example] brushing down your curtains, using this gadget to achieve a standard of cleanliness that had not yet been achieved. So the workload stayed rather the same, it’s just that standards rose.

Humanity’s long and often futile battle against dust, ABC, Late Night Live with Jay Owens, author of Dust: The Modern World in a Trillion Particles published by Hachette

THE REQUIRED ‘TIGHTNESS’ OF FEMALE BODIES AND MOVEMENT

Whereas Michelle Gelfand has studied loose/tight societies and loose/tight contexts within those societies, let’s go back to a feminist paper from 1980. When girls become women, their entire bodies ‘tighten up’, due to the extra self-monitoring required of women and girls.

In a famous 1980 essay called “Throwing Like A Girl”, Marion Young explains how changing from girl gender to woman gender requires a young woman develop a double sense of oneself. She learns that she is both a subject and an object “to be gazed at and decorated”.

A main point of the paper: to become an object is by definition to become vulnerable, because a subject acts whereas objects are acted upon.

[T]he modalities of feminine bodily existence have their root in the fact that feminine existence does not experience the body as a mere thing—a fragile thing, which must be picked up and coaxed into movement, a thing which exists as looked at and acted upon. To be sure, any lived body exists as a material thing as well as a transcending subject. For feminine bodily existence, however, the body is often lived as a thing which is other than it, a thing like other things in the world. To the extent that feminine existence lives her body as a thing, she remains rooted in immanence, is inhibited, and retains a distance from her body as transcending movement and from engagement in the world’s possibilities.

Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality, Iris Marion Young, Human Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1980), pp. 137-156 (20 pages)

Immanence: the state of being present as a natural and permanent part of something. (into + to dwell) (Not at all related to the word imminent meaning soon—intrinsic-ness would be a synonym.) Transcendence: existence or experience beyond the normal or physical level. (beyond + to climb)

BODY IMPROMINENCE AND SEDENTARY LIVES

Men have more of what has been called ‘body prominence’:

Fisher finds the most striking different between men and women in their general body image is that women have a significantly higher degree of what he calls “body prominence,” awareness of and attention to the body. He cites a number of different studies which have come to the same results. The explanation Fisher gives for this finding is that women have a higher degree of body awareness because they are socialized to pay attention to their bodies, to prune and dress them, and to worry about how they look to others.

Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality, Iris Marion Young, Human Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1980), pp. 137-156 (20 pages), from the footnotes

Basically, in writing that essay, Marion Young pushed back against male academics of the time who noted differences between men and women/boys and girls when navigating the world, and stupidly put any differences they saw down to biology. (Penises point outwards, vaginas are internal—yes, that is what some of them actually said.)

Young noted the same differences, but attributed them instead to the fact that ‘girls and women are not given the opportunity to use their full bodily capacities in free and open engagement with the world; nor are they encouraged as much as boys to develop specific bodily skills.’ It’s the old nature/nurture thing. (We now know that it’s never nature VERSUS nurture, but a constant and complex interaction between the two, with social, political and emotional influences thrown into the mix.)

Young also noted the enforced sedentary lives of women from girlhood:

Girl play is often more sedentary and enclosing than the play of boys. In school and after school activities, girls are not encouraged to engage in sport, in the controlled use of their bodies in achieving well-defined goals. Girls, moreover, get little practice at “tinkering” with things, and thus developing spatial skill. Finally, girls are not asked often to perform tasks demanding physical effort and strength, while as the boys grow older they are asked to do so more and more’

Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality, Iris Marion Young, Human Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1980), pp. 137-156 (20 pages)

Del is expected to sit still at the table. She is expected to sit still inside the house for days on end. Would the old ladies have expected the same of her brother, even though sitting quietly to do homework might also be considered a privilege?

HOUSEWORK AS (IRONIC) BODILY FREEDOM

But in “Winter Wind”, housework is a type of bodily freedom. We see Del stretch out her legs in front of a fire she has built herself. This is of course ironic, given that it also constrains women to the home. Alice Munro has never shied away from broaching difficult contradictions, and this is one of them: Housework as both freeing and constrictive. For the grandmother and aunt, housework constricts their lives. This is partly of their own doing, since not all women in the same cultural milieu are quite so keen to keep their own houses pristine and also to inadvertently express judgement about the cleanliness of other people’s houses.

The grandmother and great aunt surely imagine how their house must look to others: a progression from the teenage preoccupation with how one’s body must look to others. In another short story from the same collection, “Wigtime“, a middle-aged woman has ‘let herself go’ but, as part of this process, has transferred the same objectifying concerns to the house. Such women are never free. First it’s a preoccupation with the body, then, after marriage and middle-age desexualises women’s bodies and renders them invisible, the same limiting mindset can shift onto the house. Woman as house; house as body.

The source of [a woman’s] objectified bodily existence is in the attitude of others regarding her, but the woman herself often actively takes up her body as a mere thing. She gazes at it in the mirror, worries about how it looks to others, prunes it, shapes it, molds and decorates it.

Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality, Iris Marion Young, Human Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1980), pp. 137-156 (20 pages)

Perhaps the grandmother and great aunt have never been able to live ‘in unity with themselves’ because they are constricted by their housework.

Feminists are starting to name these types of invisible labour. I’ve heard the labour of maintaining the body ‘aesthetic labour’.

The Hustle of Being Beautiful

How can we interrogate the problems with beauty culture…while still enjoying our face masks and lip gloss?

The Waves podcast, Slate, June 2023

This discussion is nuanced, because taking care of one’s body and house can be a soothing and pleasurable act, done for the self. Alice Munro does not pass overt judgement on these elderly women and, considering the biographical material I’ve read about the author herself, I suspect Munro would be open to the idea that a house spent doing housework, keeping your wooden table nice, the hearth burning, is one way of living a perfectly good life. I believe she is saying it’s not for everyone, and like Michelle Gelfand has more recently said about loose and tight societies, each of these modes of living has its ups and downsides.

WOULD THIS STORY HAVE WORKED HAD DEL BEEN A BOY?

Not at all, I don’t think so. If women offered to ‘help’ a boy with housework, he would never have taken it personally. But more fundamentally, a boy of that era would never have had his personal freedom constrained, at least not in the way of girls. (Being sent to war as sacrifice for country is a different kind of bodily ‘constraint’.)