When writing about different temporalities in children’s literature, academic Maria Nikolajeva makes a useful distinction between ‘iterative’ time and ‘singulative’ time. These words come from Gerard Genette, who also came up with useful terms to describe story pacing.

Genette talks about three modes of time an influential book called Narrative Discourse:

‘Singulative’ (telling once what happened once), ‘repetitive’ (telling many times what happened once), and ‘iterative’ (telling once what happened several times).

Iterative Time

In an iterative sentence, it is assumed that whatever is happening has always happened and will continue to keep happening.

Iterative: ‘In the winter time the Rat slept a great deal, retiring early and rising late. During his short day he sometimes scribbled poetry…there was a good deal of storytelling.’ (In which storytelling is a ritual act). There are a lot of iterative sentences in circular stories such as Anne of Green Gables, as well as in The Secret Garden.

Singulative Time

A singulative sentence applies to an action in this particular story. Stories for children often start in the iterative then switch to the singulative.

All over town, from basket and bowl, he pilfered and pillaged, he snitched and he stole. (ITERATIVE)

He pulled them, he dragged them, he HEAVED them until… he’d carried them home to his house on the hill. (ITERATIVE)

One rascally night between midnight and four, Slinky Malinki stole MORE than before.(SINGULATIVE)

from Slinky Malinki by Lynley Dodd

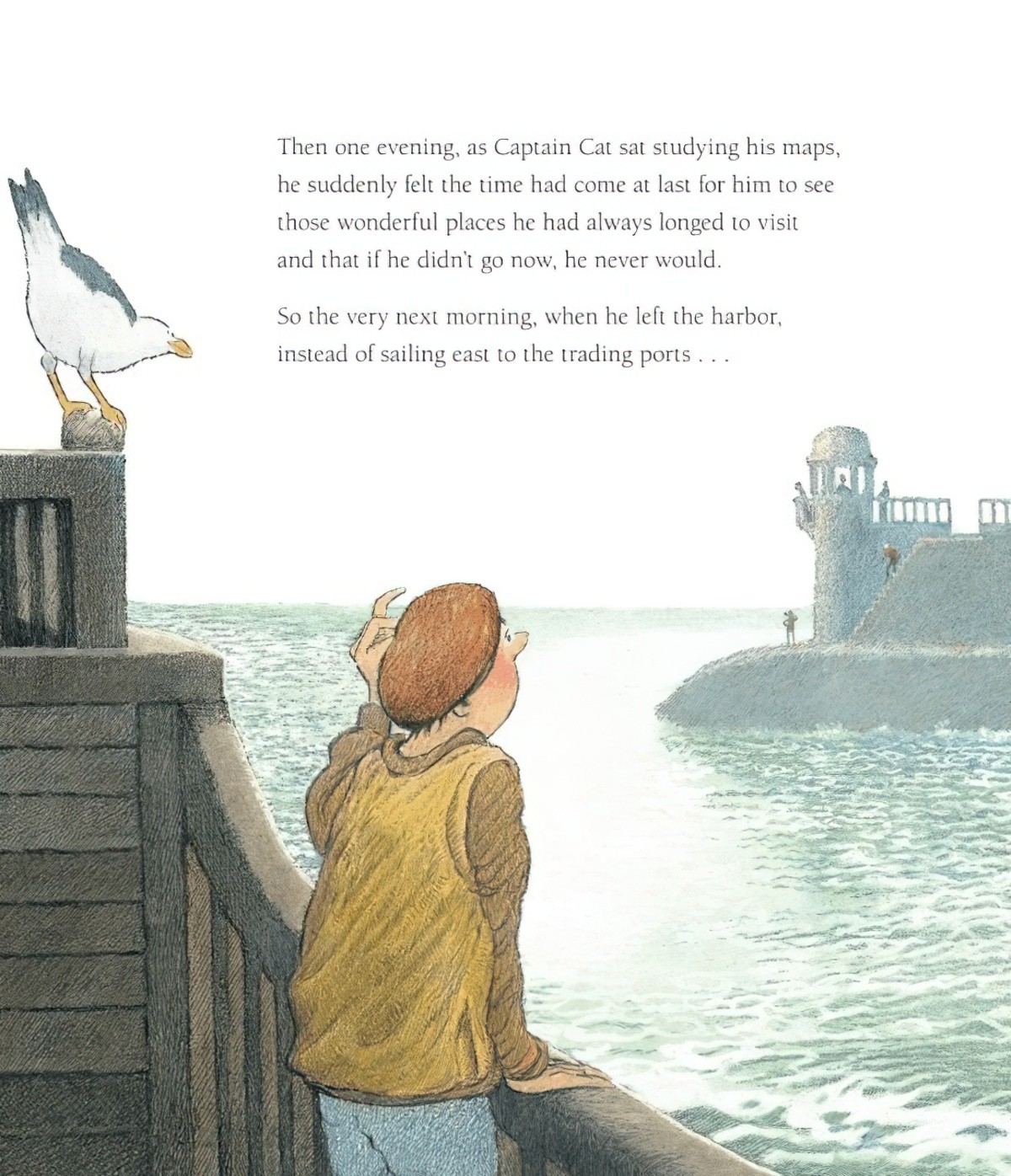

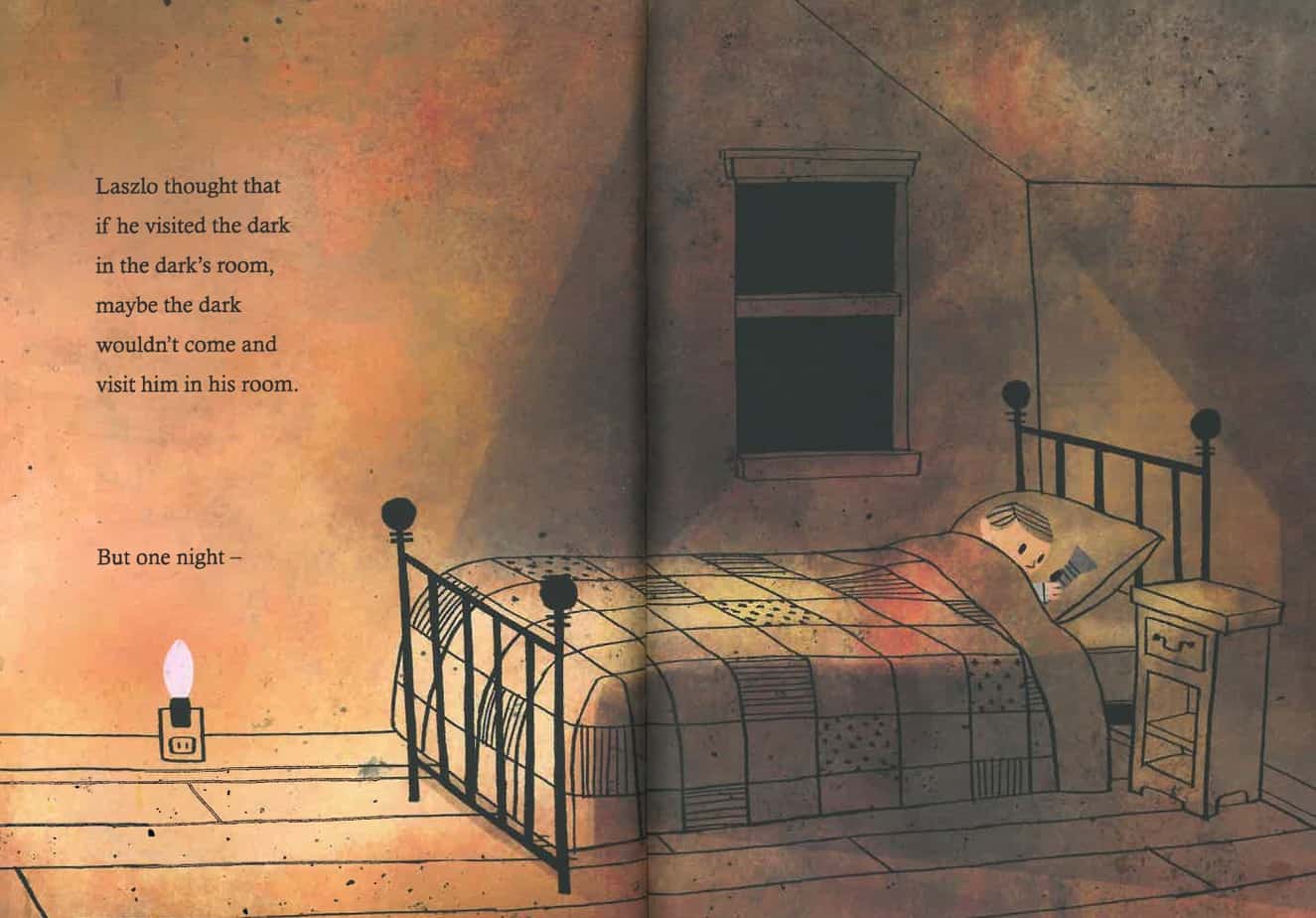

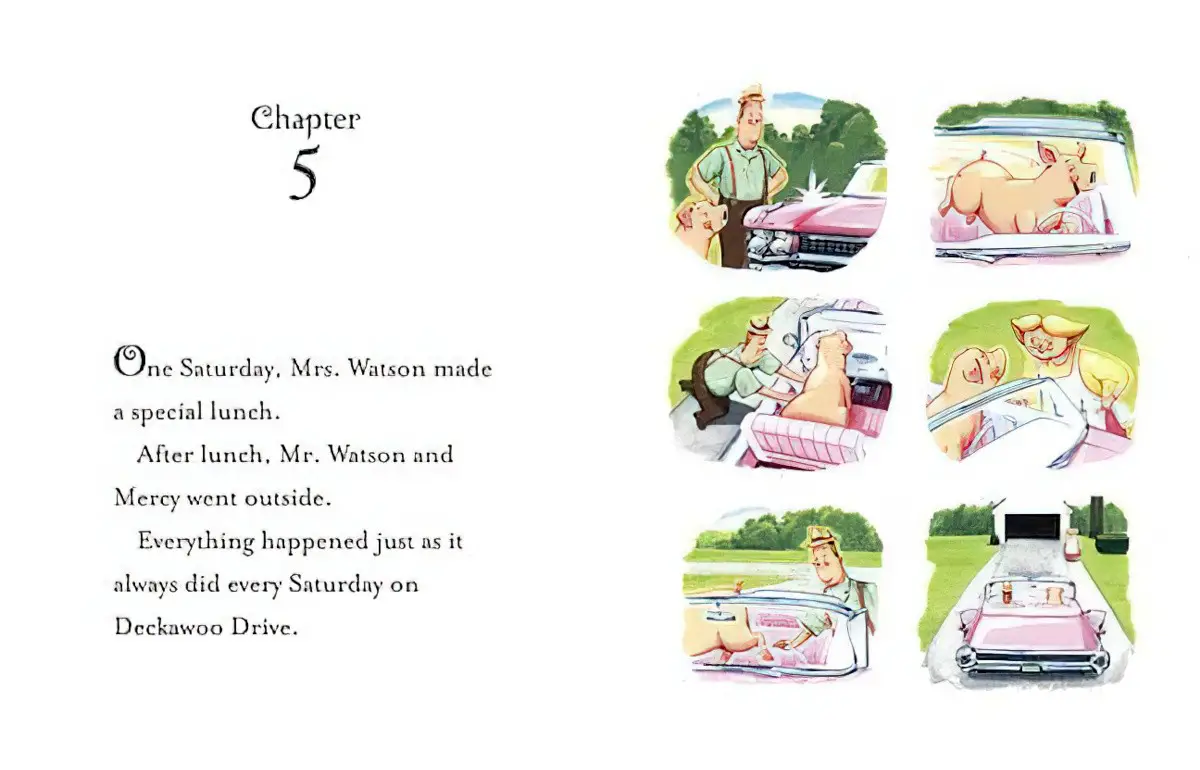

In picture books the switch to the singulative part of the story is often marked very clearly with a phrase such as ‘But one day’ or ‘However, on her fifth birthday’ or any similar variation.

You may have heard a related term: Discriminated occasion.

DISCRIMINATED OCCASION IN STORYTELLING

A specific, discrete moment portrayed in a fictional work, often signalled by phrases such as “At 5:05 in the morning . . . ,” “It was about dusk, one evening during the supreme madness of the carnival season . . . ,” or “the day before Maggie fell down. . . .”

When we read about routines in fiction, or in any kind of story, most if not all the pleasure we get from the experience derives from our anticipation of seeing the routine shattered, or, at the very least, disrupted.

Peter Selgin

EXAMPLES OF THE SWITCH

Below is the switch from iterative to singulative in The Dark by Lemony Snicket and Jon Klassen:

How The French Do It

Note that this division doesn’t necessarily hold for all languages. As James Wood writes in How Fiction Works, grammar works differently in French:

French verb forms allow [Flaubert] to use the imperfect past tense to convey both discrete occurrences (“he was sweeping the road”) and recurrent occurrences (“every week he swept the road”). English is clumsier, and we have to resort to “he was doing something” or “he would do something” or “he used to do something”—”every week he would sweep the road”—to translate recurrent verbs accurately. But as soon as we do that in English, we have given the game away, and are admitting the existence of different temporalities.

Speaking of France, there is (a translation from French) by Gerard Genette.

Genette says all sorts of things about narrative, but one thing he does in that book is he talks about ellipsis — an especially massive topic in film studies. Every story deals with ellipsis differently. Broadly, modern audiences are very used to ellipsis and will put up with more of it. Until the end of the 1800s, authors padded their novels out with a whole lot of summary between scenes, in case readers got lost along the way.

Technically, ‘degree of ellipsis’ exists on a continuum, but Genette worked out there are four main ways of dealing with a certain subcategory of ellipsis: That which concerns a story’s capacity for repetition.

GENETTE’S FOUR MAIN WAYS STORYTELLERS DEAL WITH ELIDED REPETITION

- Narrate once what happened once

- Narrate n times what happened n times

- Narrate n times what happened once

- Narrate one time what happened n times Genette calls it the Iterative, but others have called it the Frequentive. A single utterance describes several occurrences of the same event. “For a long time I used to go to bed early.” This is what we see so often in the opening of children’s books.

For more on that, see this article.

Iterative vs Singulative in Stories For Adults

While this distinction is particularly obvious in picture books for children, might we also see it in all stories?

Yes, because this phenomenon is wide in its application.

In a picture book, you can pretty reliably expect the first few pages of the book to be in the iterative, especially if the author is introducing a new character. Then, after the switch to the ‘story at hand’ (the singulative), there’s no switch back.

In a novel for sophisticated readers, there is a constant switch between iterative and singulative and the reader copes with this no trouble at all. In genre fiction such as thrillers and crime, rather than starting with the iterative, the modern requirement is for the story to grip the reader, so stories often begin in medias res. In contrast a novel which begins in the iterative lets the reader know that they’re in for a quieter, less disturbing read. Unless you get someone like Stephen King, who likes lengthy set-ups just so he can lull you into a sense of security before knocking you upside the head. It is perhaps psychological thrillers which are more likely to make use of this particular technique, since the setting is very often domestic, and domestic life is by its very nature iterative.

Consider this as an example of how widely we can utilise the terminology proposed by Genette:

The montages of nightclub signs and clinking champagne glasses in romantic comedies are iterative in function.

Film Quarterly

Incidentally, in case this is useful to you, Genette makes a distinction between ‘external’ and ‘internal’ iterations:

If they stand for a series of such evenings, they are what Genette calls generalizing or external iteration; if for one of them, what he calls synthesizing or internal iteration.

Film Quarterly

RELATED TERM

DISCRIMINATED OCCASION

A ‘discriminated occasion’ is a specific, discrete moment portrayed in a fictional work, often signaled by phrases such as:

- “At 5:05 in the morning . . . ”

- “It was about dusk, one evening during the supreme madness of the carnival season . . . ”

- “The day before Maggie fell down. . . .”

When a storyteller discriminates occasions, they lend verisimilitude to a work. The more outlandish the plot, the more useful it is to give specific times, dates and places (even if those places are fictional).

Header painting: Charles Edward Wilson – What O’Clock