**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Moons of Jupiter” is a short story by Canadian Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro, first published in the May 22, 1978 edition of The New Yorker. This short story is also the title of Munro’s 1982 collection. (In case you have access to the archives, five of these stories were published in The New Yorker between 1978 and 1981.)

We continue to find more and more moons of Jupiter. The latest were found using telescopes in Hawaii and Chile in 2021 and 2022. After follow-up observations, now we’re sure (until someone finds even more):

Astronomers have discovered 12 new moons around Jupiter, putting the total count at a record-breaking 92.

That is more than any other planet in our solar system. Saturn, the one-time leader, comes in a close second with 83 confirmed moons.

Jupiter’s moon count jumps to 92, breaking Saturn’s Solar System Record, 04 Feb 2023

This is important to our understanding of the Alice Munro’s short story: We keep having to revise what we think we know about Jupiter. (A truism which applies here on Earth, even to the people we think we know best in the world.)

In her introduction to the collection, Lorrie Moore writes that “Moons of Jupiter” has this to say about the human condition:

- people circle one another

- people are an admixture of lunacy and hard intelligence

- our various pasts revolve simultaneously around the present

- children are always in a parent’s gravitational pull, even when out of sight

- filial love has an infinitude of stories

In February 2023, Munro’s “Moons of Jupiter” was chosen by Clare Sestanovich to read and discuss with Deborah Treisman at The New Yorker Fiction podcast. (Their analysis begins at 39 minutes.)

I am reading the version which appeared in The New York Times, which has minor differences from the story as it appeared in the collection. For instance, the narrator was changed from a painter to a writer. Why? Not clear, though I did think as I read The New Yorker version that Janet could just as easily be a writer, and that Alice Munro would know how it feels to be a painter, because fame ambivalence does a number on your psyche, no matter the branch of art.

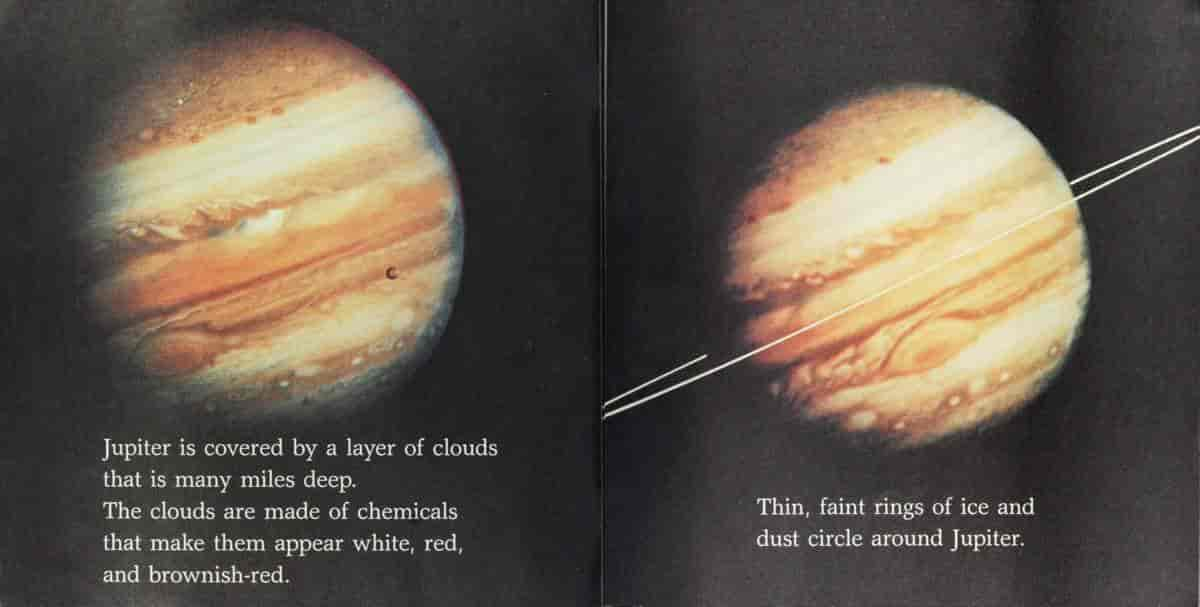

“MOONS OF JUPITER” BY ALICE MUNRO AND THE VOYAGER EXPEDITIONS

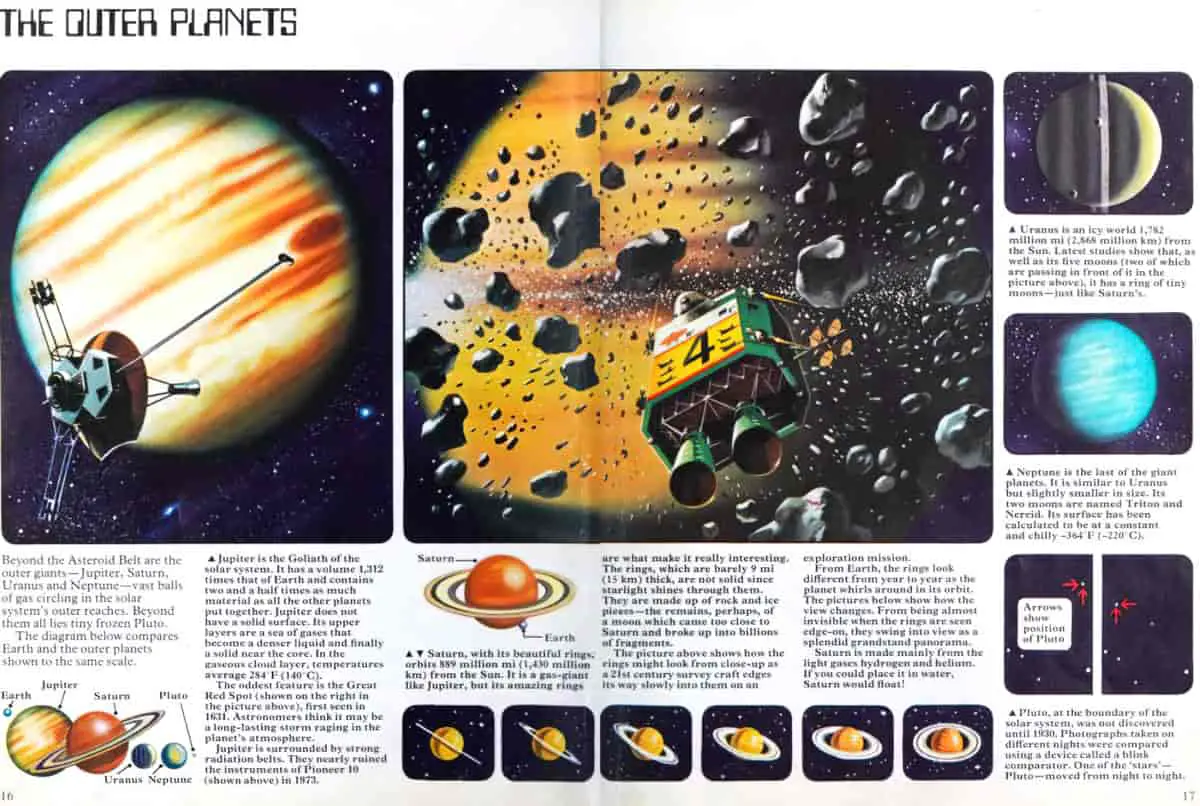

NASA launched the two Voyager spacecraft to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune in the late summer of 1977, which is no doubt why people (including writers such as Alice Munro) were thinking more closely than usual about the planets in our solar system. In 1973, Pioneer 10 had already crossed the asteroid belt and past Jupiter. Of course, the ancients knew about Jupiter because it’s visible to the naked eye. Galileo made the first detailed observations using a telescope in 1610, and it was Galileo who discovered Jupiter had moons. He was able to see four of them: Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto.

Voyager 1 reached its closest position to Jupiter in early April of 1979, about a year after this short story was first published. Voyager 1 took almost 19,000 pictures.

Voyager 2’s closest approach happened in July that same year. People now saw Jupiter like they’d never seen it before.

Fast forward to 2023, The JWST has taken even more astounding (composited, digitally deciphered) images of Jupiter with its Near-Infrared Camera, which is able to see through space dust and detect details beyond the visible light spectrum. Now we can see Jupiter’s faint rings of space dust and much tinier satellites.

Remember that word, ‘detect’. It comes in handy when deciphering the symbolic layer of Alice Munro’s short story, “Moons of Jupiter”. Jupiter’s actual moons were in the early stages of closer human detection as Munro wrote it.

WHAT DID WE KNOW ABOUT JUPITER IN 1978?

Although it took a while for Voyagers 1 and 2 to reach their closest position to Jupiter, they had already sent back some enticing images the previous year. Alice Munro’s story was published in May 1978, but on March 5, 1977, the Voyagers had sent back photos of highly detailed photos of the surface of Jupiter and its satellites. We’d suspected Jupiter had a ring system, and now we knew for sure. These rings are mainly made of dust from collisions that occur on Jupiter’s moons.

The biggest surprise discovered by the Voyager flybys: Active volcanism on Jupiter’s moon Io. Until that moment, we only knew for sure that volcanoes happened on Earth.

WHAT ALICE MUNRO CAN’T HAVE KNOWN ABOUT JUPITER WHEN SHE WROTE “MOONS OF JUPITER”

In 1995 we learned just how massive those volcanoes are on Io. Io’s volcanoes are similar to what would have been happening on Earth at the beginning of Earth’s existence. Jupiter therefore connects us to our own planet’s deep past.

The 1995 Galileo mission alerted us to salt water below the surface on Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. These moons also have an atmosphere, of sorts.

We learned that Jupiter has ammonia clouds in its atmosphere.

We started to wonder more about whether Jupiter’s moons might harbour life, in a possible habitable zone in the salt water/slush. (Gravity from Jupiter and Saturn could cause flexing in the mantle, which would generate heat and keep some of the water liquid.) Just in case, Galileo was sent on a suicide mission into Jupiter. (Ditto for the subsequent Juno probe.) We didn’t want a probe from Earth to contaminate the atmospheres of the Jovian moons with our bacteria.

Of course, we still don’t know if Jupiter’s moons harbour lifeforms, but as of 2023, the most likely place for extra-terrestrial life in our Solar System is thought to be under the ice on Europa, Jupiter’s fourth largest moon. We can’t easily see through this ice, as it’s 10 miles thick. Perhaps life is supported by hydrothermal vents. Earth examples include crabs and tubeworms. We do have plans to tunnel down there and have a looksee.

Jupiter’s largest planet Ganymede may also harbour life. However, if Ganymede has a subterranean liquid ocean, it’s not 10 miles below the surface but 60. That would be quite a drill. No wonder scientists are more interested in starting with Europa first.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “MOONS OF JUPITER” BY ALICE MUNRO

As usual, a simple plot summary does no justice to an Alice Munro short story:

Middle-aged Janet’s father is in hospital in Vancouver with heart trouble, so she travels from Toronto to see him. She finds him hooked up to a machine which prints out his heart activity.

The father first avoids, then subsequently decides to undergo surgery for a damaged valve. This is a highly risky operation at his age.

Father and daughter talk together in his hospital room. They discuss Janet’s daughters, Judith and estranged daughter Nichola, and various things to do with child-rearing and about death, including connections the mind makes to remember things you thought were forgotten.

Janet realizes that the gap between herself and her father endures between herself and her daughters. The years a child remembers best are a blur in the mind of a parent.

The day before her father’s operation, Janet visits the local planetarium. When she tells her father about it, he is able to name the moons of Jupiter from memory.

A SPIRAL (ORBITING) PLOT SHAPE WITH A SLOW BUILD

See this post on plot shapes. About spirals in particular:

I wonder if first person retrospective narratives — especially obsessive ones — might naturally follow a vortex. It’s how I’ve found lyric memoir to work; maybe it’s true of fictive versions of retrospection, too. A preoccupied (haunted?) narrator turns around and around in her hands the most potent moments of her past, gazing at repeating patterns and shapes as she spins.

Jane Alison, from her book Meander, Spiral, Explode (talking about a different story)

The spiralling has something to do with Munro’s treatment of time.

Treisman uses the phrase: ‘constant non-chronological movement’.

Why does Munro mess with time? ‘So readers get their [father and daughter’s] relationship in a decontextualized way before we are bombarded with the parallels [between Janet’s relationship with her daughter and her relationship with her father]’. Readers see the parallels; it’s unclear how well Janet sees the parallels herself, though she seems to be telling this story as a means to understanding her father and the time around his death.

Alice Munro is famous for messing with time (in her super-controlled, adroit way). That’s why a Munro short story feels as as expansive as a novel. But why has she temporally disoriented the reader in this particular story?

Perhaps to meld and merge generations. The old and the new are not as distinct as Janet thinks they are: Information on Mercury is updated when Janet visits the Planetarium. Also, father and daughter share a joke near the end about information on Jupiter’s moons being “new to us”. (Astronomers have continued to discover more and more Jupiter’s moons, to the point where they gave up naming them after mythological characters years ago.)

CHARACTERS IN “MOONS OF JUPITER”

JANET THE FIRST PERSON NARRATOR

Janet lives in Vancouver. Says her ‘headquarters’ are there. She has two grown daughters. She is a painter, with an uneasy relationship with her level of fame. She has been brought up to chase fame and then apologise for it, mostly by her father.

Her own kids, likewise, have issues with how she brought them up. On the page: The younger daughter feels the older daughter gets all their mother’s attention for living a precarious life.

The narrator feels uncomfortable with the likelihood that her daughters, partners and friends have been discussing her among themselves, no doubt airing complaints.

They would have talked about me. Judith and Nichola comparing notes, relating anecdotes; analyzing, regretting, blaming, forgiving. I wished I’d had a boy and a girl. Or two boys. They wouldn’t have done that. Boys couldn’t possibly know so much about you.

Alice Munro, “The Moons Of Jupiter”

Do you agree with Janet about the difference between sons and daughters? I’m always leery around broad gender statements, but I can understand why a mother of daughters might idealise having had sons instead (or why a mother of sons might idealize having had daughters).

JANET’S FATHER

The father’s self-deprecation and unflappable mien has translated into his daughter never feeling quite good enough.

Janet speaks in terms of her father’s ‘younger selves’, in acknowledgement that we do not remain the same person across a lifetime. It is mildly shocking to her, to see her father’s naked torso which, unlike his face, arms and hands have never been exposed to the sun and appear to belong to another, unfamiliar body.

The father had a materially poor and precarious childhood (like many of his generation), spent his life working in a factory, toiling in his garden and reading history books. Like anyone who spends their life working in a 20th century factory, his brain was severely underutilised. Reading was his mental stimulation. He is an expert on Roman emperors and the Balkan wars. This aspect of his character is important for the whole moons of Jupiter metaphor, when we are not at all surprised to learn how many of the moons this fellow can name. He has also read the books by his astronomer son-in-law.

“He never made a fuss.” Janet has inherited/learned some of his emotional reserve.

Has Janet been clinging to the wrong version of her father and estranged daughter? Even Janet’s father doesn’t seem to know himself particularly well. This seems to be a man who distracts himself with external facts and information rather than turning inwards.

It’s always interesting in fiction to observe characters who think they know themselves, then do something to show that they don’t know themselves at all. The information is still useful: Any declared self-assessments prove people have an idealised version of themselves. As an example in “Moons of Jupiter”, Janet’s father contradicts himself by saying he stayed out of his children’s business, which is good, and then immediately gets into his daughter’s business by offering a (possibly) deathbed opinion on her marriage split.

In other Alice Munro stories, girls are expected to self-efface, to remain invisible. The father of this story stands out as a bit different. He expected his daughter (not his son) to become famous, though also? He expected her to apologise for it. Jupiter is big; Janet is expected to become big, yadda yadda, rather than some satellite to a man.

JUDITH

The narrator’s younger daughter. Grown, living with her partner, whose name is Don. She is clearly used to her mother seeming more interested in the health and safety of big sister Nichola than about her. Judith considers her older sister the baby of the family. The sisters are sometimes on good terms, sometimes not.

NICHOLA

The narrator’s older daughter by four years. Nichola “used to be a student at the Conservatory”, which I’m guessing refers to The Toronto Conservatory of Music established in 1886 with a name-change in 1947. The school expanded hugely in the post war period.

Anyway, Nichola was subsequently a cocktail waitress and is now out of work.

Nichola has moved out of her run-down apartment and announced herself incommunicado for a while. Family estrangement is more common than fiction would have us believe but Alice Munro doesn’t shy away from it. Another example of a child who has inexplicably removed himself from his mother is “Deep Holes“, which Munro wrote decades after this one. In that story, the mother must learn to come to terms with her grown son cutting her off for ambiguous reasons — a loss psychologists might call ‘ambiguous loss’ (a term which comes from Dr Pauline Boss, coined around the time this story was written). “Silence” (2004) also deals with estrangement.

TOM

Janet calls Tom at one point — a former lover — and although they had no appointment together, she feels strangely annoyed at him for not being there for her when she wants him. She recalls a time when he stood her up in a restaurant.

What is the story reason for the existence of Tom?

Tom may tell us something about Janet’s psychological need to take a breather from being the ‘Jupiter’ of a sandwich generation, holding two generations on either side of her together, yet watching them slip from her grasp.

At different points in the story, both father and Nichola are described as an ‘escaped child’. Tom, a former lover, is alluring because he let Janet go.

As an aside, for this same reason, the con-non-con fantasy is thought to be so popular with women is as follows: The Bad Boy (TM) is alluring (in fantasy) because this archetype is not needy. He takes control. ‘Needy’ is associated with children, and there’s no turn-off as powerful as children (by evolutionary design, surely).

IN-LAW TROPES IN FICTION

Alice Munro fills a gap in popular culture regarding the relationship between grown children and their parents. As evidence of in-laws in pop culture I offer examples of pages from TV Tropes, in which the most common in-law stories are told from the point of view of the younger generation:

Stories about what it’s like to be an older adult navigating sons- and daughters-in-law are far less common, partly due to whose voices the dominant culture thinks worthy of telling.

Ground covered in “Moons of Jupiter”: How it feels to have grown children, to see them partnered up, to see your children navigate adult relationships with each other and judge your parenting lacking. What do your children’s partners know — or think they know — about you?

To cover this ground, Alice Munro has given us a woman who we would now say is “the sandwich generation”, navigating relationships with her own parent as well as with her grown children. This offers readers a double perspective. As our narrator comes to terms with how she sees her father’s separate selves, she reckons with how her own children see her own selves — a view not based on some objective reality, but rather on a disturbingly random mish-mash of what is remembered, and where her daughters happen to be in their lives right now. Her daughters will never see her objectively. It’s impossible.

A recent Australian example of a story written from the mother-in-law’s point of view is crime novel The Mother by Jane Caro, in which a coercively controlling son-in-law separates the mother’s daughter from her family as part of his abuse. It’s up to the mother to get her daughter back.

Just like the garden, the fuse box, the bills, bin night and blown light bulbs, this was just something else she’d now have to take care of herself.

Recently widowed, Miriam Duffy is a respectable North Shore real estate agent and devoted mother and grandmother. She was thrilled when her younger daughter Ally married her true love, but as time goes by Miriam wonders whether all is well with Ally, as she moves to the country and gradually withdraws, finding excuses every time Miriam offers to visit. Their relationship has always had its ups and downs, and Miriam tries to give her daughter the distance she so clearly wants. But is all as it seems?

When the truth of her daughter’s situation is revealed, Miriam watches in disbelief as Ally and her children find themselves increasingly vulnerable and cut off from the world. As the situation escalates and the law proves incapable of protecting them, Miriam is faced with an unthinkable decision. But she will do anything for the people she loves most in the world. Wouldn’t you?

“I went to the show at the planetarium,” I said to my father. “It was very exciting—about the solar system.” I thought what a false and silly word I had used: “exciting.”

“Moons of Jupiter” by Alice Munro

I’ve heard it said that there’s no common word for ‘exciting’ in Swedish, who have a deserved reputation as a reserved culture (except when you meet them in a sauna).

SYMBOLISM OF THE HEART MONITOR

Janet’s father is hooked up to a heart monitor, exposing that which should, by rights, be hidden. The metaphor is useful: The exposing of something normally hidden away.

THE MOTIF OF DETECTION

Clare Sestanovich figures we’re not supposed to know what it is being exposed, and it’s this Unknown Thing which is frightening. Janet ‘can’t quite figure out her relationship to intimacy’. Words throughout the story like ‘detect’ and ‘detach’ form a motif to illuminate how we are always striving to monitor and detect other people, ‘without ever quite seeing clearly’.

In the hospital, Janet and her father clearly know each other very well, but their interactions suggest a careful remove. Treisman calls their conversation a ‘badgering cheerfulness.’ Father and daughter are formal with each other, ‘trying to negotiate the comfortable distance to keep [separate] from somebody’.

Writers are told to make conversations oblique to keep them interesting. Meaning, every conversation should really be about something else. Alice Munro is a master of that, exemplified by the conversations Janet has with her father as he prepares for death.

This theme is explored further in the scene with Nichola: ‘Nichola would never know.’ Even if she did have leukemia as a child, young Nichola would never have been told her diagnosis. ‘The cruel irony there is that the narrator herself will never know (the details of Nichola’s life, due to estrangement).’ (Sestanovich)

In each scene, something threatens to be exposed. Janet fears the loss of her father. She also fears the loss of her own daughter, not through death this time, but due to a deliberate removal on the daughter’s part.

Deborah Treisman says, ‘Anticipating loss, she withdraws love, and goes through the motions of [grief] so that the person isn’t supposed to be aware that she’s withdrawn [her love]’.

Janet’s emotional hurdle: Just as she accepts her father’s imminent demise, he decides to go ahead with the surgery anyway.

There is one jump forward in the text, alerting readers to the reality that the father has already died at time of writing. But we never know when exactly this happened, or whether he came through the operation alive. We must sit with this ambiguity ourselves.

SYMBOLISM OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM IN “MOONS OF JUPITER”

Jupiter, home to the first moons discovered in our solar system, functions in some ways like a mini solar system.

NASA

BASIC FACTS ABOUT JUPITER

- Jupiter is HUGE (318 Earths, and 2.5 times the size of all the other planets combined)

- If it got any bigger it would literally start to get smaller. Jupiter can’t get any bigger than it is without increasing in density.

- Astronomers have called Jupiter a ‘failed star’. Like a star, Jupiter has plenty of hydrogen and helium, but it doesn’t have enough mass to trigger a fusion reaction in its core. (That’s how stars generate energy.) It would actually need to have 70 times the mass to do that. (In the story, Janet isn’t a failed anything, but this doesn’t stop her feeling that way at times, if she judges herself by someone else’s standards.)

- Made of gas (“a gaseous giant”)

- Has rings around it but they’re not especially visible

- Fifth planet from the Sun

- The fastest spinning planet in the Solar System (A day is just under 10 Earth hours long)

- One Jupiter year is almost 12 Earth years

- Cloaked in mystery (there’s much we still don’t know — a perfect metaphor for this story)

- Named after a sky-god who Romans believed oversaw all aspects of life. He is thought to have originated from the Greek god Zeus.

- Of all the planets in our Solar System, Jupiter has had the most probes flying by over the decades. Every expedition goes past Jupiter, sometimes utilising its mass for gravity assist. (Gravity Assist: Harnessing gravity to speed up or slow down a probe.)

MYTHOLOGY OF THE PLANETS

By most counts, Jupiter has between 80 and 92 moons, but neither number captures the complexity of the Jovian system of moons, rings and asteroids. The giant planet commands thousands of small objects in its orbit. Scientists are getting so good at spotting tiny moons orbiting distant, giant planets that the International Astronomical Union has decided the smallest will no longer be given mythological names unless they are of “significant” scientific interest.

NASA

What else is Janet losing, aside from her father? Sestanovich says Janet is losing ‘the conviction that she ever knew him to begin with’. The mythology Janet has built around her father is less robust and self-sufficient then previously thought.

Alice Munro writes a dialogue between father and daughter in which they talk about the Roman and Greek mythology in regards to the planets, but Munro is also teaching us how to read her story: She is getting readers to think about the mythology of the characters in our own lives, and the stories we tell ourselves about those closest to us.

In stories, the characters who are not on the page can be as significant as those who are. Sestanovich says, ‘You can be having an effect on people who are not right there in your orbit.’ Not on the page: Nichola, the former lover, the former husband. All of these people have a continued influence on Janet as she goes about her day-to-day life.

I’m sure there are some gravitational metaphors to be had there, plus dark matter and dark energy.

THE PLANETS, CHOICE AND FATE

Clare Sestanovich points out that this is a story about choice. Like planets and their moons, we, too, are locked into a system, unable to escape from our set orbits. Janet has no choices to make in this story. She goes to the Planetarium for lack of other ideas; perhaps she tries on a dress as a way of trying on a different self, she eats in a restaurant and laments not having a different plan with her former lover.

This lack of plan-making is striking because characters generally do have and make choices in fiction — often in the form of a moral dilemma with no clear-cut good choice.

This doesn’t hold true for melodrama, interestingly. In melodrama (a legitimate and popular paradigm in fiction, not an insult), characters are locked into their lives and must deal with crap that comes their way. (This explains why melodrama has historically been more popular with women — women have historically enjoyed less self-determination, locked in by their reproductive biology and by a gender hierarchy with men at the top. When this story was published, women had only been allowed to acquire credit cards separate from their husbands for four years. In America, the sexual harassment act had only just been passed.)

WHY DOES JANET VISIT THE PLANETARIUM?

What is the narrative reason for this visit?

While there, Janet learns that something she thought she knew about Mercury turned out to be wrong. As astronomers learn more about the Solar System, we must update our knowledge. She gets irrationally angry about this. Feels lied to. Something else is going on there: Her father, too, is not the uncomplicated, non-regretful man she always assumed him to be. He has many selves, just like everyone, and she can’t begin to know them all, just as she can’t begin to know all that is out there in the wider universe.

The Planetarium, though, is a contained microcosm of all that is out there, and when leaving such a place, it’s comforting to feel you know quite a bit about it. But it’s all an illusion. A Planetarium is a heterotopia. As Foucault used it, a heterotopia describes a space which has more layers of meaning or relationships to other places than immediately meet the eye. The Planetarium contains the universe for us in such a way that existing in the outside (non-Planetarium) world is a bearable vastness.

But leaving the utopian container of the Planetarium risks opening Janet’s eyes to things she isn’t ready to deal with: Not just the utter vastness of the universe, but the vastness contained in us all, with our multiple selves, our contradictions, our lapses in memory melding and merging into (and shaped by) the clearer memories of our own children.

By the way, when describing the concept of heterotopia, Foucault used the example of a garden, which is now the go-to example: Gardens contain vegetation from far and wide in the same space (regionally and globally). The act of gardening is an act of organisation. Your favourite flowers/bushes go in a favoured spot. This leads to incompatible elements but a sense of trying to establish order.

[Gardens] exclude much, not least time and change … Indeed they have more in common with aquaria and terraria than with nature.

Ian McHarg, “Nature Is More Than A Garden” in The Meaning of Gardens: Idea, Place, and Action, Mark Francis, 1990

A STORY OF EXQUISITE AMBIVALENCE

Connected to the theme of choice (or lack thereof), Sestanovich also considers “Moons Of Jupiter” an ‘exquisite story about ambivalence’. Via Janet’s backstory we learn that she has most certainly made dramatic choices in her life:

- becoming a professional painter

- leaving her husband (or perhaps he left her — the default assumption in a break-up is that the woman has left the man, I find.)

Janet must sit, too, with the ambivalence of not minding that her daughter has become distant from her, but also willing to reco11nnect should she be offered the opportunity. She avoids calling Nichola herself, but hopes every phone call is her.

What about the sheer size of Jupiter? When writers choose Jupiter, as opposed to other planets in our solar system, we must assume they have chosen it partly for its mass.

This is a very difficult position for women to be, and actually, as someone born the year this short story was published, I had thought our (Gen X) generation of women and non-binary femmes most affected by dint of straddling rapidly changing gender expectations. But no, it was felt earlier, by women Janet’s age —Alice Munro’s age, The so-called Silent Generation a.k.a. the Traditionalist Generation. The generation is generally defined as people born from 1928 to 1945. Munro was born in 1931, which makes her at the older end of it. She’s actually closer to earlier, spectacularly named The Greatest Generation. I appreciate, as a young Gen Xer, that when you’re close to the cut-off, you do feel on the border of two generations, because such borders are naturally fuzzy.

Anyway, why is Alice Munro’s generation called the Silent Generation?

Unlike the previous generation who had fought for “changing the system,” the Silent Generation were about “working within the system.” They did this by keeping their heads down and working hard, thus earning themselves the “silent” label. Their attitudes leaned toward not being risk-takers and playing it safe.1

Wikipedia

IS “JANET” ALICE MUNRO?

As I read, I consider Janet a bit of an Alice Munro stand-in, for better or for worse. (We tend to do this to woman writers more than to men, which can be a problem.) Janet is astute, self-aware, reflective, which is why Alice Munro could get away with turning her into a writer in The Moons of Jupiter collection. Alice Munro is herself a writer, herself got divorced during the Second Feminist Wave, had two children in Vancouver. Significantly, her own father died after heart surgery in Toronto in the 1970s.

Many decades later, Alice Munro has undergone heart surgery herself, but doctors have come a long way with heart health and Alice’s surgery was successful.

Was this story a young Alice Munro reflecting on her father and reckoning with her own future? Surely the death of a parent always provokes some of that.

“Moons of Jupiter” feels autobiographical in the way Margaret Atwood’s Moral Disorder collection: The main characters are fictional, but anyone who knows about the author can hardly avoid reading the stories as semi-autobiographical, at least. ♦

FURTHER READING

Gas giants like Jupiter may be more common than we thought, at least in some parts of the galaxy.

For a long time, we assumed that our Solar System was the very model of what a star system should look like: a few rocky little planets orbiting moderately close to the Sun, with giants of gas and ice farther out. But we were wrong. Many of the star systems we know of have “hot Jupiters,” gas giants orbiting perilously close to their stars, even closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. It’s rare to find a gas giant like Jupiter in the outer reaches of a star system.

THE UNIVERSE MAY BE TEEMING WITH JUPITER-LIKE GAS GIANTS, NEW STUDY SUGGESTS

THE MOONS OF JUPITER (1982)

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings I: The Connection“

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings II: The Stone in the Field“

- “Dulse” also in the July 21, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Turkey Season” also in the December 29, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “Accident”

- “Bardon Bus“

- “Prue” also in the March 30, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Labor Day Dinner” also in the September 28, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd“

- “Hard-Luck Stories“

- “Visitors“

- “The Moons of Jupiter” also in the May 22, 1978 edition of The New Yorker