**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

If you’re still in high school or college, visualise your best friends as middle-aged adults. How do you think their lives will turn out. If you’re long past high school and college (like me), how did the lives of your young adult friends pan out?

Have you ever met a friend from your youth after a decades of estrangement and been surprised at how their lot in life feels somehow, at the same time, both inevitable and surprising? If our childhoods map out our futures, they do so in unexpected ways.

Tim Winton’s short story “Big World” explores these themes in a masculine way and in an Australian setting. For a story of two female high school friends reuniting for the first time after many years, let’s take a close look at “Wigtime” by Canadian writer Alice Munro.

WHERE TO READ “WIGTIME”

“Wigtime” first appeared in the September 4, 1989 edition of The New Yorker. Find it also in Friend Of My Youth, Munro’s 1990 collection, or in The Best American Short Stories 1990, edited by Richard Ford.

SETTING OF “WIGTIME”

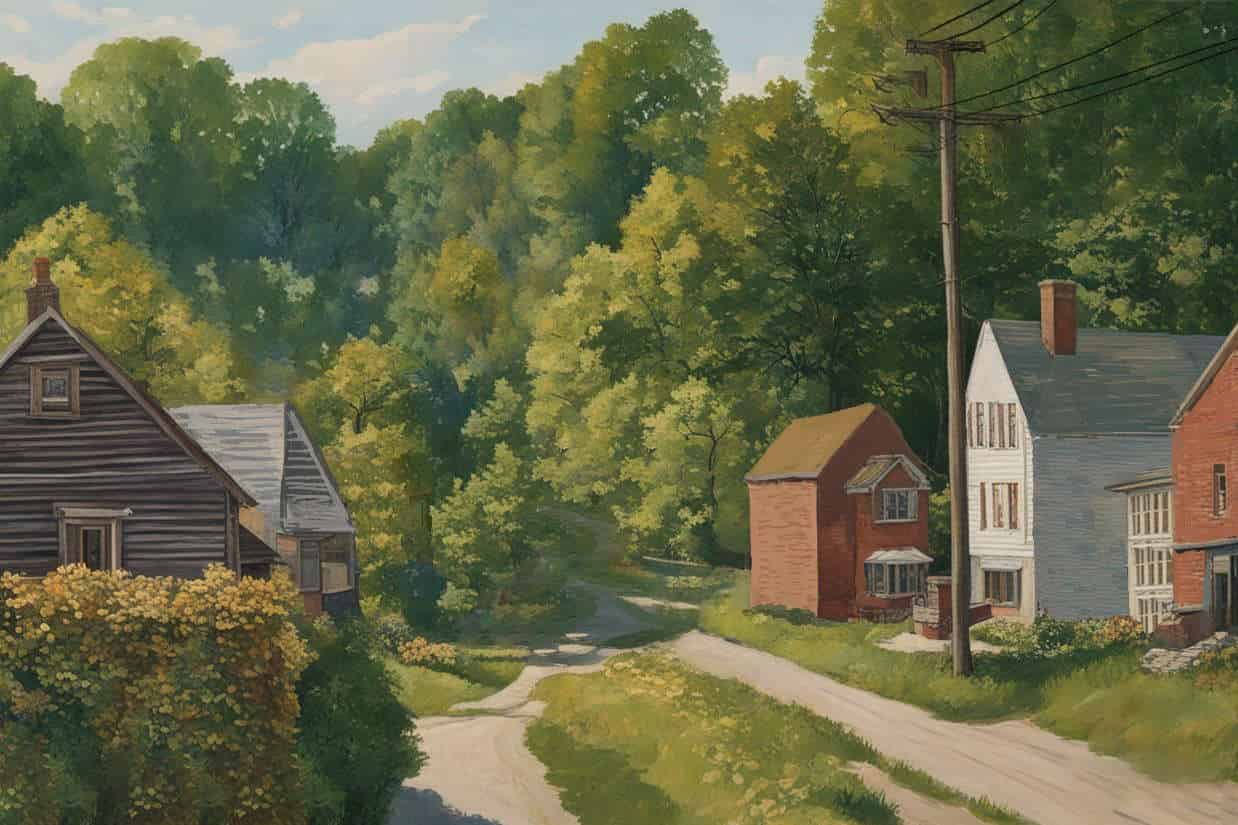

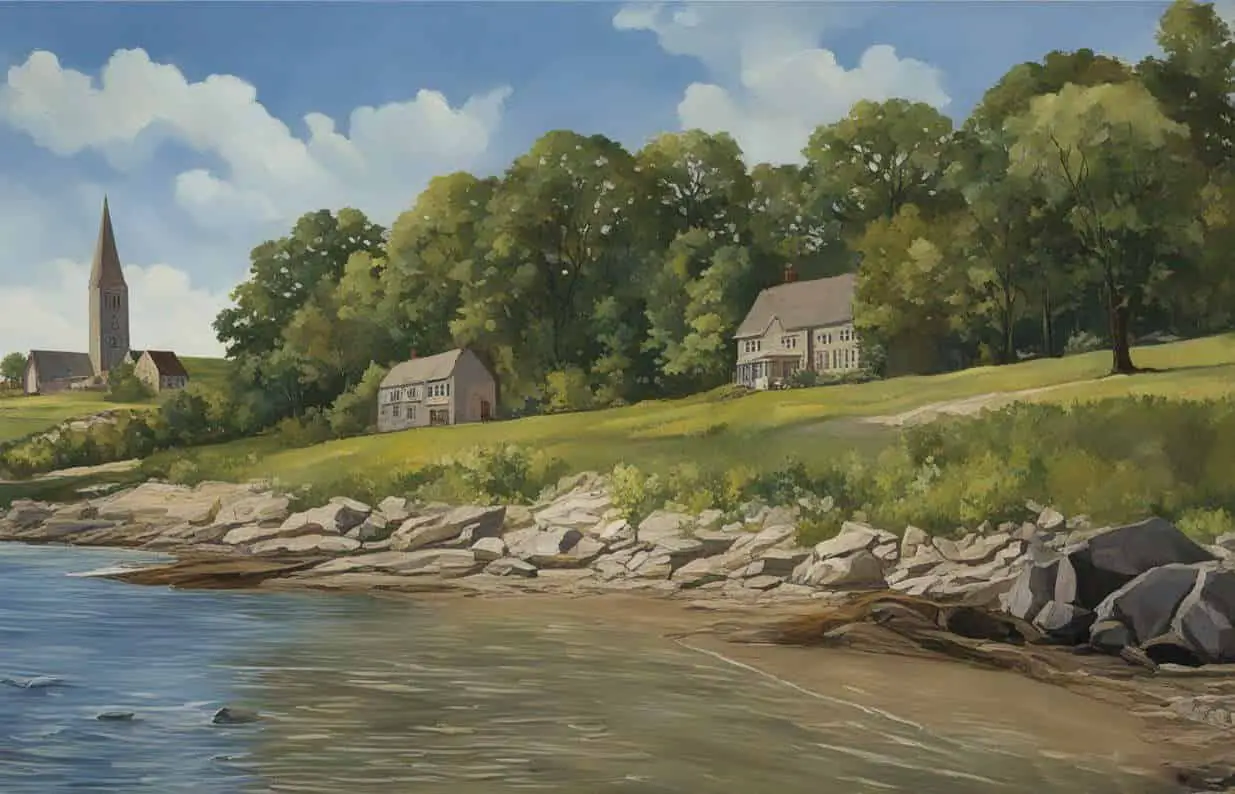

“Wigtime’ is set in a very small fictional town called Ashfield, nearest town Walley. Walley is also a fictional town and is understood to be based on the real town of Goderich in Huron County, Ontario. Munro based many of her fictional towns on Goderich, naming them Tupperton, Tiplady, Wawanosh or Mock Hill.

GODERICH

Goderich is a “water town”, sitting on the eastern shore of Lake Huron and at the mouth of the Maitland River. It has been voted Canada’s Prettiest Town and is notable for its beautiful sunsets. Today the population is ~8,000 and tourism is the main industry. The bay features a great swimming spot due to its shallow, reasonably warm water.

We might expect the population to be bigger than 8000 today, except for its relative remoteness (even for a Canadian town).

Historically the main industries were fishing, salt mining and flour milling. A modern rail station built near the harbour helped Goderich to become a thriving shipping location.

Goderich is exposed to wind coming off the lake which can turn the weather quite chilly even in summer. Ontario gets a tornado on land about once every eight years and in 2011 Goderich was in the firing line. The famous town square had to be rebuilt.

The Canadian army opened one of its big air training facilities in Goderich in 1939 at Sky Harbour, which operated until about six months before the end of the war.

Goderich also has its dark history, with an historic jail which was the site of Canada’s last public hanging in 1869. (Here in Australia, we were much slower to understand the barbarity. Our last hanging happened uncomfortably recently, in 1967, despite protests. Capital punishment wasn’t abolished in all Australian states until 1985.)

ALICE MUNRO’S FICTIONAL CAREGIVERS

Munro famously wrote a lot (actually a proportionate amount) about women in caregiving roles. Munro was herself in a caregiving role as a teenager and young woman because her mother lived with a form of Parkinson’s disease for years before she died.

Aside from “Wigtime” Alice Munro used her own experiences to write the experiences of fictional caregivers in:

- “The Peace of Utrecht“

- “Images“

- “Memorial”

- “The Ottawa Valley”

- “Winter Wind”

- “Spelling”

- “Friend of My Youth”

- “Accident”

- “Chaddleleys and Flemings: Connection”

- “Family Furnishings”

- “Soon”

- “The Ticket”

WHAT HAPPENS IN “WIGTIME”

“Wigtime” opens with a woman called Anita who has returned to her hometown of Walley after an adult lifetime away.

Anita is no longer a nurse but has returned from somewhere else to keep an eye on the care of her ailing mother. At the story’s opening the mother has since died.

While at the hospital, Anita reconnects with another middle-aged woman she was very friendly with in high school. Margot has heard that Anita’s back in town. Anita hasn’t seen Margot since they were seniors back in 1948-49. Margot invites Anita to her beautiful house by the lake and the pair of them drink sangrias on her deck.

Margot now has five children, and by Anita’s estimate, spends all of her energies on her beautiful, “long and low” house with grey brick, overlooking the lake.

There’s a bit of passive-aggressive tension between the two women when Anita asks Margot if she “works”. The 1980s were a turning point for women, who were told they could now “have it all”: the career, the home, the family, the husband. But men had not picked up the slack in the house. So when Margot is asked if she “works”, she’d know exactly what Anita means, but takes the opportunity to remind her friend that keeping a beautiful house and feeding hungry sons is a job in itself. Via the narration, we learn that Anita is somewhat dismissive of Margot’s house proudness. Readers are also invited to judge Margot, who is very proud of her living room, yet the whole room is staged to the point where Anita understands it isn’t a room that is used. It is only for admiring. Likewise, she feels mildly chastised and also amused when she gaffes by calling ‘almond’ paintwork ‘cream’.

Anita has already heard that Margot’s husband has done well. He runs a tourist bus company with a fleet of vehicles.

Through Anita’s eyes the reader is also invited to judge Margot in her home. Unlike her house, Margot is showing her age:

Margot was wearing green flowered shorts and a matching top. Her legs were thick and marked with swollen veins, the flesh of her upper arms was dented, her skin was brown, mole-spotted, leathery from lots of sun.

Wigtime

At this point the reader is yet to get a description of Anita herself, but we can already deduce that, unlike Margot, Anita has no time for fripperies such as home décor. She also seems to feel that some of Margot’s energies should be expended on her body rather than on her home and family. By her body language, Margot has shown us that Anita looks younger, and perhaps because Anita has remained childfree, is less mature as well. Anita now feels there’s a gap between them, which isn’t justified. After all, the two women are the very same age. She doesn’t need to be talked down to.

This dynamic reminds me of Marilla Cuthbert and Rachel Lynde a la Anne of Green Gables, though the friendship between these two unlikely best friends is better explored in Anne With an E, I feel. Rachel Lynde positions herself as the expert on all things child-rearing as she has a large number of grown children herself. (I find it strange that we never meet any of them.) Not only that, but Rachel considers herself more of a rounded person — an adult, and world-wise in a way that Marilla could never be, not as a single woman living in her natal home with her brother. However, it is shown across the story that Marilla is equally adept at the parenting role as Rachel, and in fact Marilla comes to understand Anne at an emotional level which Rachel has probably never managed with her own children.

Back to “Wigtime”. Note that when Margot leans forward to flip Anita’s hair, Alice Munro is introducing us to the motif of hair which begins in the title. Readers still have no idea what “wigtime” could refer to.

ANITA AND MARGOT AS GIRLS

After a double carriage return Munro takes us on a flashback to their youth, where we learn that Anita and Margot each had very different home lives as girls. In many ways the two young women were very close and talked easily. Their backgrounds were identical on paper, both growing up as girls on a farm in the township of Ashfield, which readers can deduce is nearby. (They’d have bussed in to Walley for their high schooling.)

Alice Munro herself grew up on the outskirts of a town (on a fox farm) and she has written a number of girls whose social capital was limited by her coming in to town from out of town. Anita and Margot feel less privileged and wealthy than their Town (Walley) counterparts. (We see this also with Helen in “Day of the Butterfly“.)

The two young women fooled themselves into believing they shares everything, but they each held important things back. Namely, Anita didn’t realise at the time how much her best friend was affected by the domestic violence of her father. Margot wanted to be a nurse so she could leave Walley for good. Margot’s appearance of fortitude derived from wanting to avoid ending up like her mother, who she considered pathetic and weak for crying. Many readers will also either have endured a violent father themselves, or else had a friend with a scary father, such is the ubiquity of domestic violence.

Despite Margot’s father having plenty of energy to hit his family, he left it up to Margot and her mother, the women of the family, to do the hard manual labour of milking the cow and forking hay (as well as all the interior housework, we can assume).

Meanwhile, Anita had a more fortunate home life with a seldom violent father (typical of the era), and enough support to at least dream of becoming something great — an archaeologist or else a fashion model. (This speaks to a beauty differential between the two girls.) But Anita knew it was above her station to admit to wanting those things, so kept such thoughts to herself. Her brothers did the heavy barn work, leaving her with enough time to study, and dream.

It will be ironic to readers at this point that Margot never did leave the area, and has instead built a decent life for herself in Walley. Despite the more fortunate upbringing, it was Anita who managed to get out. We don’t yet know where she’s been all this time, though we will later learn that Anita married a doctor while working as a nurse in Yukon and has since divorced. Anita has no children of her own and has recently completed a doctorate in anthropology at the University of British Columbia.

WHAT’S REALLY GOING ON?

At this point in the story, Munro has primed readers to expect that not all is as it seems with Margot. Like Anita, we are suspicious of her beautiful house near the lake, with its perfect décor and its perfect living room which cannot be used. Even the sangria feels like an affectation — an exotic drink from Spain and Portugal, when the pair of them grew up drinking strong tea typical of country folk, as Munro is sure to mention later in the narrative.

Another irony: Despite Margot dreaming of becoming a nurse as a means of getting out, it was Anita who became one, as a means of getting out.

Note the stark difference between Margot’s childhood house — a duck farm with its constant reminder of death — and the beautiful house she has made for her adult self. Anita remembers the ‘horrible smell of feathers’ — part of the symbol web concerning hair.

PROSPECTS FOR WOMEN OF ANITA AND MARGOT’S GENERATION

Historically, the nursing trajectory of both girls speaks to the lack of opportunities available to young women of the era. For those coming of age in the post WW2 years, middle-class women all over the West were being pushed back into the home to free up Jobs for the Men, or else into the limited caring roles of teaching and nursing, which they were expected to quit once they became mothers. Nations were all about restoring the population. The burden of making humans fell mostly on women.

Biology is destiny for 1940s young women. Also, upbringing is destiny. It’s not as easy to escape your socioeconomic class as ‘work hard and succeed’ folk would have us believe.

TERESA AND ALSACE-LORRAINE

Readers are introduced to the character of Teresa Gault, who both girls knew from their teenage years. Teresa was an immigrant from Europe who ran the local highway store where Anita and Margot used to seek refuge after trudging through the snowy fields in winter. Also, coffee was a reminder that there’s more to life outside their limited lives of strong, country tea. Once entering the store, they could briefly imagine other lives.

Locals find Teresa to be a chronic oversharer. Readers can deduce that Teresa is desperate to be included in the community and, unfamiliar with rural Canadian conservatism, isn’t reading the room when she tries to force friendships with other women by telling them private things about her sex life with her husband. She came to Canada as a war bride from a place called Alsace-Lorraine — once part of the German empire, now region of modern France.

The term “war brides” refers to women who married Canadian servicemen overseas and then immigrated to Canada after the world wars to join their husbands. The term became popular during the Second World War but is now also used to describe women who had similar experiences in the First World War.

War Brides: The Canadian Encyclopedia

Historically, German and France have fought over who should claim the region of Alsace-Lorraine. Many terrible things happened there under Nazi invasion during WW2, which is less than a decade ago within the earlier setting of Munro’s narrative. Long story short, we can deduce that a woman in Teresa’s position would of course take the opportunity to leave by marrying a Canadian if she could. She must have been desperate. She had believed there was nothing but polar bears in Canada.

Via Teresa, readers are encouraged to consider what it means to ‘run away’ from your home. For different reasons, this is playing out again with Margot in particular. Margot wishes to run away from her violent father; Teresa ran away from Nazi invasion, mass murder and the banning of the French language.

For the record, France took it back in 1919 after WW1, Germany took it again in 1940, then France got it back again in 1945 at the end of WW2. They’re had it ever since. Might Munro be using the recent history of a faraway country to illuminate a similar state of affairs? Namely: An older woman marries a younger man who then marries a younger woman, and then much later in life, a younger woman again (the babysitter). Historical events don’t map perfectly onto the characters in Munro’s story, but the general gist is reminiscent. After all, Munro utilised a similar writing technique in “The Peace of Utrecht” which is also about a woman who has returned to her hometown to care for an ailing mother after a long time away. (In that story, conflict with another woman concerns a sister rather than a childhood friend.)

Also with Teresa, Munro once again draws readers’ attention to the difference between appearance and reality. It is said by the townsfolk that Teresa is much older than she looks, and significantly older than her husband. She dyes her (thinning) hair, wears make-up and dresses exotically in a femme fatale sort of way.

The young women look carefully at her face and accoutrements. Perhaps Teresa was so desperate to leave Alsace-Lorraine that she lied even to Reule about being younger than her age? After all, women have a use-by date. The baby-making functionality of women comes to the fore when Teresa worries if the cold Canadian weather might freeze the girls’ eggs.

REULE

Readers do not yet know that Teresa’s husband was Reule — the very same man Margot later married, and who remains married to her to this day. This connection is left as a reveal.

At the close of the 1940s, the girls know 28-year-old Reule as their school bus driver as well as Teresa’s husband. These days, school bus drivers are charged with a duty of care, but Reule keeps order on his 1940s school bus by threatening to throw students off if they misbehave, and he sometimes does just that, even during the freezing cold Canadian winter. Anita remembers discussing with Margot whether Reule counts as handsome. They have many such conversations — intimate on the surface. Together they divide Reule’s body into composite parts and decide that he is not handsome, though it is clear that he has a sexual pull on Anita. We can assume he had this effect on them both, though Margot’s public persona was that of an independent woman with a contempt for men.

[W]hen Anita was anywhere near him she had a feeling of controlled desperation along the surface of her skin. It was something like the far-off beginning of a sneeze. This feeling was at its worst when she had to get off the bus and he was standing beside the step. The tension flitted from her front to her back as she went past him.

“Wigtime” by Alice Munro

Part of Reule’s pull comes from the fact that the girls are privy to details about his intimate life, which comes via the oversharing Teresa — ostracised by the married women of the community, turning instead to very young women for company. (It’s clear from Teresa’s contempt for women who refuse to groom themselves to her own high standards that she has partly ostracised her own self.)

As 18-year-olds, Anita and Margot are brand new to conversations between adult women about their husbands, fertility and sex lives. To know so much about this man in particular is novel and exciting, and imbues Reule with more allure than he would otherwise garner.

Although Margot does not admit to liking Reule at the time, Anita knows her friend well enough to understand that Margot’s macho attitude doesn’t entirely match her feelings, and that although she’s not classically pretty, her defiance is itself a drawcard for a certain type of man. She understands what so many young women take a while to see: Pretty isn’t everything. (Perhaps it takes a pretty girl to see it.)

MARGOT, ANITA AND MOTHERS

Readers don’t see much of Anita’s ailing mother but we are told she had ambivalent feelings about her daughter: She feels Anita’s life has been a waste, presumably because she never lived a normative life by providing grandchildren. At the same time, she is grateful to have a daughter who is available to come back and care for her. The reader can fill in the gaps: If Anita had indeed provided grandchildren, she may not be as available to care for her own mother, especially if, say, one of her children were themselves disabled.

Back to the scene in Margot’s beautiful house, where the two women have been drinking sangria, several of Margot’s sons arrive home with their friends and the house turns to chaos. Margot must have had a late-in-life baby because Debbie is only ten, dressing up as a dragonfly. Margot makes a snide remark about her daughter’s weight: “A hefty dragonfly”. There is no real peace between any of these mothers and daughters.

Margot has no real opinion when Anita shares that she recently finished her PhD in archaeology, only to enquire what she might do with such a thing. This will be familiar to any woman who chooses a life of the mind, and no doubt comes from Alice Munro’s personal experience of sharing with women that she’s a writer. Some women are admiring, others dismissive. Another group can’t quite figure out why you’d do such a thing. Margot is one such person — utilitarian in nature, in her element when surrounded by the bustle of family life.

Surely those grown sons could be more independent. They still rely on their mother to find things around the house, provide the food information, know the family schedule. When we watch Margot in progress, it’s easy to conclude that Margot in complicit in their learned helplessness. When Anita notices that she doesn’t have the same reaction around Debbie, this is partly because Debbie has been brought up differently. Note that Debbie has arranged her own dragonfly costume. But when she comes in to show it off, her mother delivers a snide, unnecessary comment (completely reminiscent of boomer parenting of the 1980s and 90s, I might add).

Do mothers like Margot at times despise their daughters precisely because they have parented their girls to more independent than the sons? (It likely started the other way around, resulting in a cycle.) Let’s not forget, Margot was a neglected girl herself, and I’d imagine she’s the sort of mother who’d say, “You don’t know how easy you have it, my girl.”

Now the story flashes back to the late forties, when Margot and Anita decide to stop frequenting the coffee shop. They have several reasons for avoiding the place, but chiefly, they’re “sick of Teresa”. Through the window, Teresa waves at them as if playing peek-a-boo. Munro is reminding us that Teresa is stuck in a childlike stasis. Margot and Anita are sick of her because they have matured. Munro writes a paragraph about the changing of winter to spring — the girls have metaphorically come into bloom. Teresa’s oversharing and her strange ideas have lost their novelty. We can deduce that Teresa will move on to a younger pair of high school girls who will embrace as their “sophisticated” adult bestie for a while.

Straight women can be immune to other women but not to the same sorts of men. So it is in the case of Margot’s reaction to Teresa versus Teresa’s husband, Reuel. Reuel is every bit as immature as Teresa. Anita is starting to see that, despite her inconvenient attraction to him, especially after Reuel chastises them for singing the very same slightly ribald song he sings himself on the bus (in front of children, no less). The double standard irks Anita, but she is surprised to learn that Margot has fallen under his spell, suddenly intent on impressing him.

1940S MISOGYNY

Small gender injustices are peppered all through the work of Alice Munro:

Anita woke up in the night with amazing pain … Her father did not think it proper to phone the doctor before daybreak, but her mother phoned him anyway.

“Wigtime”

Note that untreated appendicitis is a life-threatening event which justifies waking a doctor, who is presumably on call. Three weeks in hospital is an extraordinarily lengthy stay and it would seem her appendix ruptured. Note, too, that women’s pain is regularly dismissed, especially when the woman is young (or Black or queer…). Everything abdominal in a biological female is first attributed to “women’s troubles”. Only once that “likelihood” is crossed off do doctors move on to asking what else might be wrong. Too often they don’t move on, with catastrophic results for women and girls.

Munro turns this event into a character arc for Anita’s mother, who learns not to take her husband’s advice and gets her driver’s licence.

Later, an aunt visits with the terrible news that “after an operation like this one always gets fat”. What could possibly be worse for a young woman than getting fat? Even for teenage girls, the spectre of impending demise looms large, and it’s all about appearance to others. Paradoxically, when the terrible thing is internal, and might really kill you, women have trouble being believed. Her father never does understand — or acknowledge to himself — that his daughter came perilously close to death and that she really does need to be in hospital. Alice Munro describes all of this in such a mundane, straightforward way it’s difficult not to be enraged by it. This is everyday misogyny, 1940s version.

Alice Munro’s voice can seem deceptively direct, but it expresses an elliptical and poetic sort of vernacular realism in which the ceaselessly analytic voice appears to be utterly natural, as if it were the reader’s own.

Joyce Carol Oates, 2009

Is it worse when a woman is a misogynist? I don’t believe so, not in a moral sense, though it certainly feels worse. Especially when that woman is your own mother. Anita’s mother arrives at Anita’s bedside to break the salacious news that Margot has run off with the bus-driver, proving the mother correct all along about Margot being an oversexed homewrecker.

A MASTERFUL WRITING TECHNIQUE

Deep sigh. Contemporary readers will have a different response — a response not yet ubiquitous when The New Yorker first published this story in 1989. Now, I’d wager most of Munro’s readers are able to articulate exactly how the vulnerable teenager with an abusive father fell for the only man in her life who paid her any attention.

Anita’s mother is ostensibly angry because Margot has been ‘sneaky’ about it. A true friend would have told Anita what she was up to with a married man. I am highly suspicious that this was the mother’s chief concern. Aside from the pleasure of Being Right, Anita’s mother is concerned about the stigma of Margot sticking to Anita due to their close friendship. Sure enough, further down, Munro confirms my suspicions. She has managed my reader response perfectly:

Anita had a feeling that her mother was angry at her not only because she’d been friends with Margot, a girl who had disgraced herself, but for another reason as well.

“Wigtime”

However, my take is different from Anita’s 18-year-old take: That she wishes her own daughter could be the centre of some drama. Again, Alice Munro has managed this like the pro that she is:

- Describe a situation

- Let the reader suspect a different interpretation

- Confirm via the viewpoint character that there is a different interpretation

- Offer, via a more naïve viewpoint character, a different interpretation which is still not quite right.

This leaves room for the young Anita’s character arc. Of course she doesn’t understand the full story as an 18-year-old who has just had the terrible realisation that her own father would have sacrificed her life for the sake of saving money on hospital fees, or bothering the on-call doctor. She’s not exactly high in self-esteem. To make matters worse, she’s just realised she’s lost her best friend. Her own mother is on a completely different emotional level, chiding her for her choice of language rather than listening to the emotion behind Anita’s words.

YOUNG WOMEN AND STIGMA

Alice Munro explored stigma in a story from her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades. In “An Ounce of Cure” we meet the stigmatized character as an older woman and, by this time her life, she realises the singular incident which led to her stigmatization as a “loose girl” was the best thing that could’ve happened to her.

Let’s see if we get any such insight from the older Margot, who we mostly only see via the viewpoint character of Anita.

Oh yes, Reuel’s wife Teresa tried to poison herself by drinking undiluted household bleach, though I guess she didn’t drink much of that if she neither killed herself nor wound upp in the same hospital where Anita stayed. On the other hand, Alice Munro’s phrasing suggests that Teresa drank bleach — separately, on another occasion — as an abortifacient.

The news was that Teresa had tried to poison herself. She had recovered. The store was closed. Teresa was still living there, but Reuel had taken Margot with him and they were living here, in Walley. In a back room somewhere, in the house of friends of his. They were living together. Reuel was going out to work at the garage every day, so you could say that he was living with them both. Would he be allowed to drive the school bus in future? Not likely. Everybody was saying Margot must be pregnant. Javex, was what Teresa took.

“Wigtime”

What a masterful writing technique. Alice Munro conveys the frenetic speech patterns of the outraged mother and also leaves us with the view that, for Teresa, drinking bleach is a thing she does now and then, because these are the awful moral decisions women face when there’s no control over their own bodies. The positioning of that final sentence regarding the Javex could be referring back to the first sentence of the paragraph as antecedent, or it could be Anita thinking to herself, “If my best friend is pregnant, she could maybe do what Teresa always does in these situations: drink Javex.”

More generally, poisoning and womanhood go together, in contrast to other forms of violence more commonly associated with men.

Another example of an Alice Munro story featuring women and poison: “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You“, which also happens to feature a man who runs a tour bus company.

ANITA’S UNEXPECTED REACTION

When writing a story, it’s easy to skip steps 2 and 3:

- How would I react to this story event?

- How is my character different from me?

- In which ways might my character differ from me in their reaction to this story event?

Unless we go through this process we’re unlikely to write interesting, realistic and rounded characters, or rather, we’re missing out on that maestro level of characterisation.

It is surprising to me — yet completely believable — that Anita is lying in her hospital bed while the entire town gossips about Margot, and she still wishes she were Margot. Given her lack of maturity and her low self-esteem, it does make sense that she’d wish such a scandal for herself.

See also: Unexpected Emotional Responses In Fiction, in which I include another Alice Munro example.

How did Margot end up with the beautiful house?

As a story-within-a story, related to readers via a mixture of narrative summary and dialogue, Margot explains to Anita over sangria that five years ago she received a phone call from an unknown woman that her husband Ruele was seeing another woman.

Margot had ideas about who, and set about finding out. She purchased a set of clothes which made her look like a different sort of female archetype altogether. Note that there are only a few main archetypes for women to choose from:

- The Good Girl

- The Bad Girl

- The Wife

- The Witch

As a 1980s take on Teresa’s 1940s femme fatale look, Teresa disguised herself using make-up, tight clothing and an expensive wig. She drove in a rented van to the beach resort where Ruele was staying. She was shocked to discover him not with a woman, but with the high school girl who babysits their kids — the girl she always felt sorry for.

Note that this is history repeating itself. Margot was once the girl who people could legitimately feel sorry for (though they mostly blamed her). She then became the ‘homewrecker’ girl. Some of Margot’s notes are directed at the girl, though she must understand deep down that this is all on the husband.

Rather than confront her cheating husband directly, Margot left her aggrieved notes where she knew Ruele would be sure to find them. The notes warned him to watch out for the ‘vice squad’. She knew this got to him because he takes tablets when he has an upset stomach, and upset stomach is caused by stress.

Importantly, Margot was in no a position to divorce her husband, not with five children together. So in a pragmatic view of the marriage contract, she used her husband’s infidelity as bargaining power and that’s how she got him to build their beautiful house which overlooks the harbour. These days, whenever Ruele steps out of line, all Margot needs to say is, “Wigtime” and this shuts him up.

Having shared a story about personal tragedy and drama — with a hefty dose of comedy — Margot requests information on how Anita’s marriage ended.

Anita is unable to be so forthcoming. Presumably this is because she’s not so practised as Margot in telling her own tragic tale.

Note that Alice Munro lampshades the fact that this sequence of events sounds like a scene from melodrama by telling the reader that it sounds like something you might see on screen.

THE HAIR MOTIF

Let’s list the times hair has come up, or something ‘hair adjacent’:

- Margot has gone grey whereas Anita’s hair has kept its colour. (More likely she colours it.)

- There’s the horrible smell of feathers burning in Margot’s childhood farmhouse at the duck farm.

- Teresa’s thinning hair

- Margot’s complaint about all the grotty houses she had to live in until she felt she could petition for the beautiful house beside the lake — houses with horrible brown hairy material underneath the horrible carpet.

- Margot’s expensive wig as disguise

Note that Alice Munro is well-known for her linoleum. As Katherine Mansfield is known for writing about ‘the snail under the leaf‘, Alice Munro asks us to consider the rot beneath the linoleum in her domestic dramas about ordinary lives. In this story she asks us to take a peek at what’s ‘under the carpet’ — it’s something hairy. She’s talking about felt underlay which, in the 1980s, was revealed to frequently be a source of asbestos. I’m also thinking at this point about Angela Carter, and her re-visioning of the ‘Little Red Riding Hood” fairy tale: “hairy on the inside”.

But what do this hair symbolism add up to in “Wigtime”?

In most of these instances the hair has something to do with falsity.

- Anita colours her hair so that her appearance is more in line with her youthful, single woman’s outlook on life in which education never ends.

- Teresa pretends to be younger than she is, though is betrayed by her thinning hair.

- Carpeting hides the horrible, hairy material which reminds Margot of the skin of some beast.

(I’m now unsure whether I should include the feathers in Munro’s symbol web of hair as that is doing something a bit different.)

When Margot puts on that wig, she is reclaiming the falsity of everything. The wig empowers her. Note that when she throws the disguise away in a roadside bin, she does this with some regret. (Munro’s exact phrasing made me laugh out loud.) But the wig — functioning metonymically as ‘disguise’ and also for ‘the life a housewife imagines she might have led’ — has done its job.

Just as Anita’s mother was forever changed by the event of saving her daughter’s life during a ruptured appendix, this event changed Margot’s life forever. In both cases, individual empowerment did not exactly turn them into feminists. Far from it. But, each in their own way, both of these mothers — divided by a generation — managed to claim something for themselves.

Margot has transformed herself from a Wife to a Witch (Burlesque Witch subtype).

Rather than explain what I mean by Burlesque Witch, I’ll let you read what I already wrote. (Long story short, she’s a modern, comedic spin of The Wife of Bath.)

THE ENDING

Like a number of stories (e.g. “The Wind Blows” by Katherine Mansfield) this one ends with a ship metaphor. When Margot tells Anita about Teresa’s dementia, and her belief that she is still on the ship full of war brides, she uses a phrase which is similar to the oft-repeated mantra: “We are all in the same boat”.

Who is “all” in this paragraph? I believe Margot is speaking specifically about women, or about the women in the story. Each woman has a life which went very differently, but underneath the carpet, the woolly felt looks just the same.

STORIES IN FRIEND OF MY YOUTH (1990)

- “Friend of My Youth” in the January 22, 1990 edition of The New Yorker

- “Five Points” in the March 14, 1988 edition of The New Yorker

- “Meneseteung” in the January 11, 1988 edition of The New Yorker

- “Hold Me Fast, Don’t Let Me Pass“

- “Oranges and Apples” in the October 24, 1988 edition of The New Yorker

- “Pictures of the Ice“

- “Goodness and Mercy” in the March 20, 1989 edition of The New Yorker

- “Oh, What Avails” in the November 16, 1987 edition of The New Yorker

- “Differently” in the January 2, 1989 edition of The New Yorker

- “Wigtime” in the September 4, 1989 edition of The New Yorker