“The Signal-man” (1866) is a ghost story by iconic English author Charles Dickens. If you’ve ever fantasised about leaving your open office or customer service job to work alone in a tiny box in the middle of nowhere, unbothered and free to get on with your straight-forward but very necessary job, this might be the story for you.

WHERE TO LISTEN

HOW DO I GET A JOB IN THE MIDDLE OF NOWHERE AS A SIGNALMAN?

First, the bad news. You’d have to travel back in time.

A signaller is an employee of a railway transport network who operates the points and signals from a signal box in order to control the movement of trains. Some signallers are women. The job of signallers in boxes next to railways started in the early 1800s. At first they were called the Railway Police. They were as important as air traffic controllers today.

Early signallers would hang out in their signal box until a train passed by. Then they would check for the red tail lamp on the last carriage of a train to ensure nothing had fallen off. Then they’d write it down in a Train Register Book. These books were pretty large and heavy. Signallers recorded train movements and every communication that happened between other signallers at different boxes. They didn’t actually talk to anyone. They communicated via bell codes.

Sounds pretty cruisey, but this was a stressful gig! You had no computer back up. Keeping trains on the right tracks and apart from each other was entirely up to you and you had to stay awake.

Since the early 1800s, the job description of a signaller has changed a lot due to computerisation. Centralised Rail Operating Centres now do the work originally conducted in signal boxes. Old buildings are often repurposed by communities (e.g. for cafes or community projects) if they’re sufficiently distant from a working railway line.

You can still find many signal boxes throughout Britain and other British colonies, notably India, South Africa and along the three east coast states of Australia. (The Australian signal system is especially ridiculous because the signal colours weren’t shared between states!)

Oh, there was no good news, by the way. Death comes to us all.

Oftentimes in stories and metaphor, the train track symbolises our linear human experience of the passing of time. (Astrophysicists tell us that’s not actually how time works; none of the pop science communicators has ever managed to help my brain understand how space and time are the same thing. Congratulations and a stiff ticket if you are one of the few who can get your brain around that.)

What else do you associate with trains? Tunnels, probably. Tunnels (man-made caves) have a whole symbolism of their own. Train tracks are also frequently set either above or below the surrounding land. In this case, the narrator must go down a steep slope before reaching the train track. He descends into the underworld.

To get a sense of the setting, there’s a 1976 BBC adaptation of “The Signalman”.

Charles Dickens was himself in a railway accident. He was lucky to survive. This story is certainly an outworking of the trauma he experienced after that experience, and from which he never recovered. It is extremely creepy (though a coincidence nonetheless) that Dickens died five years to the day after the accident.

The Signalman by Charles Dickens

WHAT HAPPENS IN A NUTSHELL

When you first start reading, you might have a little trouble figuring out where you are. This is deliberate disorientation on Dickens’ part. He wants the reader to feel as weirded out as this guy does, simply out for a stroll. Imagine a railway line set deep in a cutting, leading into a tunnel. The signalman’s box is down there right next to the track, near the entrance to the tunnel. There’s a red light at the tunnel entrance. (In this story it’s referred to as a ‘death light’.) The signalman is a middle-aged guy who carries a white light. The narrator doesn’t seem to be carrying a light of his own. At least, that’s not mentioned.

It’s mid-1800s in England. A learned guy, maybe a doctor, is staying at a country inn. We don’t know what he’s doing there. This guy is presented in statu nascendi (without backstory). Because who cares. This is cosmic horror. He might die anyway so don’t get too attached. Also, he could be any of us. We’re meant to paste our own selves onto him.

There’s not much in the way of evening entertainment out in the countryside. So our unnamed narrator goes for an after dinner stroll. He catches sight of a signalman standing on the tracks. For some reason he can’t quite explain he’s wanting to know more about this guy. So he calls out.

The signalman looks at our narrator like he might be a ghost.

But our narrator is not a ghost. ON THE PAGE. (I THINK HE’S A GHOST. Real people have other things to do than wander around bothering people trying to do their jobs.) He decides to spend the evening, and a number of evenings after, hanging out in the signalman’s box, learning what he does for his work, coming to the conclusion that he’s a smart guy and definitely not got a screw loose.

Eventually the signalman finds the words to confide in him. There was an accident on that thar line and ever since he’s been seeing ghosts of the killed. They call out to him from inside the mouth of the tunnel, in exactly the same way as the narrator just did.

The narrator decides to come back at 11pm one evening. Logical though he is, now he’s starting get the spookies. This signalman seems perfectly sane and intelligent, and the narrator can’t find an excuse to disbelieve the guy’s ghost story, not even when he says the ghost’s been ringing his bell (but not so as others could hear it, or see it moving). You know, in a ghostly kind of way.

Nek minnit, our narrator returns to the signal box to a grisly scene. The signalman is dead on the tracks. He’s been called by a ghost into the tunnel just as a train was coming. Those ghosts were playing Grim Reaper.

By the way, one hand across the face serves as a motif throughout this story. I didn’t have it clear in my head exactly what this looked like until I saw the short 1976 film. But here’s something similar, involving unappealing cats rather than ghosts but heigh ho:

‘Halloa! Below there!’

When he heard a voice thus calling to him, he was standing at the door of his box, with a flag in his hand, furled round its short pole. One would have thought, considering the nature of the ground, that he could not have doubted from what quarter the voice came; but, instead of looking up to where I stood on the top of the steep cutting nearly over his head, he turned himself about and looked down the Line. There was something remarkable in his manner of doing so, though I could not have said, for my life, what. But, I know it was remarkable enough to attract my notice, even though his figure was foreshortened and shadowed, down in the deep trench, and mine was high above him, so steeped in the glow of an angry sunset that I had shaded my eyes with my hand before I saw him at all.

‘Halloa! Below!’

From looking down the Line, he turned himself about again, and, raising his eyes, saw my figure high above him.

‘Is there any path by which I can come down and speak to you?’

He looked up at me without replying, and I looked down at him without pressing him too soon with a repetition of my idle question. Just then, there came a vague vibration in the earth and air, quickly changing into a violent pulsation, and an oncoming rush that caused me to start back, as though it had force to draw me down. When such vapour as rose to my height from this rapid train, had passed me and was skimming away over the landscape, I looked down again, and saw him re-furling the flag he had shown while the train went by.

I repeated my inquiry. After a pause, during which he seemed to regard me with fixed attention, he motioned with his rolled-up flag towards a point on my level, some two or three hundred yards distant. I called down to him, ‘All right!’ and made for that point. There, by dint of looking closely about me, I found a rough zig-zag descending path notched out: which I followed.

The cutting was extremely deep, and unusually precipitate. It was made through a clammy stone that became oozier and wetter as I went down. For these reasons, I found the way long enough to give me time to recall a singular air of reluctance or compulsion with which he had pointed out the path.

When I came down low enough upon the zig-zag descent, to see him again, I saw that he was standing between the rails on the way by which the train had lately passed, in an attitude as if he were waiting for me to appear. He had his left hand at his chin, and that left elbow rested on his right hand crossed over his breast. His attitude was one of such expectation and watchfulness, that I stopped a moment, wondering at it.

I resumed my downward way, and, stepping out upon the level of the railroad and drawing nearer to him, saw that he was a dark sallow man, with a dark beard and rather heavy eyebrows. His post was in as solitary and dismal a place as ever I saw. On either side, a dripping-wet wall of jagged stone, excluding all view but a strip of sky; the perspective one way, only a crooked prolongation of this great dungeon; the shorter perspective in the other direction, terminating in a gloomy red light, and the gloomier entrance to a black tunnel, in whose massive architecture there was a barbarous, depressing, and forbidding air. So little sunlight ever found its way to this spot, that it had an earthy deadly smell; and so much cold wind rushed through it, that it struck chill to me, as if I had left the natural world.

Before he stirred, I was near enough to him to have touched him. Not even then removing his eyes from mine, he stepped back one step, and lifted his hand.

The story opens in medias res with a snippet of dialogue. Although it seems throwaway, this dialogue is important. (See the repetition in paragraph three.)

It’s not clear until the second sentence of the second paragraph that this is a first person narrative. This storyteller is an intradiegetic narrator. What’s he even doing out here? Who knows, but there wasn’t much doing in 1866. Later it becomes clear that he’s out on an after-dinner stroll. He goes for long walks, and this signalman captures his attention. Is he a flaneur? He is staying at an inn, so perhaps he is visiting the countryside as a tourist.

“Something remarkable”, something the narrator cannot quite put into words, despite having had time to reflect on the strange incident. This trick is used by writers of cosmic horror. It is effective when the reader is able to imaginatively fill in this verbal deficiency of the narrator.

With people on train tracks there’s always that ticking clock threat of the next oncoming train.

When we address people and they don’t reply, this is a specific kind of loneliness. We can feel solipsistically as if we are surrounded by automatons. (Or ghosts! Notice the ‘vapour’.)

“Precipitous’ is more common these days. (Both mean ‘steep’.) Don’t you love the word ‘oozier’?

Something tells me ‘dark and sallow’ isn’t meant to be a compliment.

Dickens makes full use of the symbolism of altitude. The narrator begins high then descends to a lowly place, into Hell, basically. In storytelling, the tunnel is often a portal to another world. (Tunnels and caves are symbolically similar. One is manmade.)

The narrator is making use of all senses. Before electricity proliferated after sunset, people really were better at navigating the dark. In the work of Charles Dickens, and also of Thomas Hardy, characters regularly demonstrate after-dark skills lost to those of us muddling our way blindly through dark nights, forgetting to look up at the sky for navigation, or feeling about with our hands and feet. Unfortunately, even for the darkness-adept, the sky cannot be seen when in a tunnel. For a mid 1800s person, the tunnel is the scariest kind of dark — the kind of dark which discombobulates even the most adept navigator of the night.

This was a lonesome post to occupy (I said), and it had riveted my attention when I looked down from up yonder. A visitor was a rarity, I should suppose; not an unwelcome rarity, I hoped? In me, he merely saw a man who had been shut up within narrow limits all his life, and who, being at last set free, had a newly-awakened interest in these great works. To such purpose I spoke to him; but I am far from sure of the terms I used, for, besides that I am not happy in opening any conversation, there was something in the man that daunted me.

He directed a most curious look towards the red light near the tunnel’s mouth, and looked all about it, as if something were missing from it, and then looked at me.

That light was part of his charge? Was it not?

He answered in a low voice: ‘Don’t you know it is?’

The monstrous thought came into my mind as I perused the fixed eyes and the saturnine face, that this was a spirit, not a man. I have speculated since, whether there may have been infection in his mind.

In my turn, I stepped back. But in making the action, I detected in his eyes some latent fear of me. This put the monstrous thought to flight.

“I said” could have been edited out, but Dickens wants us to remember that this is a narrated story, told by a regular (though learned) guy, not by an adept storyteller. Therefore, I guess, we should believe him. He’s hardly in the business of spinning yarns, right? (Unlike the author himself…)

Again, we are reminded that this is a regular guy telling a story. (He tells us he’s a bit shy. I’m not convinced about that.) He can’t remember the exact words. Of course he can’t. He’s too spooked.

The blood symbolism of the red light is probably so obvious it doesn’t need mention.

Originally, ‘saturnine’ related to lead. Later it meant gloomy or melancholy.

They each suspect the other of being a ghost. At this point in the story, the reader also doesn’t know if either of them is a ghost. Is this a Sixth Sense situation?

“You look at me,” I said, forcing a smile, ‘as if you had a dread of me.’

‘I was doubtful,’ he returned, ‘whether I had seen you before.’

‘Where?’

He pointed to the red light he had looked at.

‘There?’ I said.

Intently watchful of me, he replied (but without sound), Yes.

‘My good fellow, what should I do there? However, be that as it may, I never was there, you may swear.’

‘I think I may,’ he rejoined. ‘Yes. I am sure I may.’

His manner cleared, like my own. He replied to my remarks with readiness, and in well-chosen words. Had he much to do there? Yes; that was to say, he had enough responsibility to bear; but exactness and watchfulness were what was required of him, and of actual work–manual labour he had next to none.

At this point I’m really wondering if the narrator himself is a ghost.

How do desk workers feel about this narrator calling ‘manual labour’ ‘actual work’? Wasn’t Dickens himself a desk worker? Even the narrator seems to be a scholar or doctor. One thing I’ve learned about life is that everyone always underestimates the requirements of everyone else’s actual job.

To change that signal, to trim those lights, and to turn this iron handle now and then, was all he had to do under that head. Regarding those many long and lonely hours of which I seemed to make so much, he could only say that the routine of his life had shaped itself into that form, and he had grown used to it. He had taught himself a language down here–if only to know it by sight, and to have formed his own crude ideas of its pronunciation, could be called learning it. He had also worked at fractions and decimals, and tried a little algebra; but he was, and had been as a boy, a poor hand at figures. Was it necessary for him when on duty, always to remain in that channel of damp air, and could he never rise into the sunshine from between those high stone walls? Why, that depended upon times and circumstances. Under some conditions there would be less upon the Line than under others, and the same held good as to certain hours of the day and night. In bright weather, he did choose occasions for getting a little above these lower shadows; but, being at all times liable to be called by his electric bell, and at such times listening for it with redoubled anxiety, the relief was less than I would suppose.

He took me into his box, where there was a fire, a desk for an official book in which he had to make certain entries, a telegraphic instrument with its dial face and needles, and the little bell of which he had spoken. On my trusting that he would excuse the remark that he had been well-educated, and (I hoped I might say without offence), perhaps educated above that station, he observed that instances of slight incongruity in such-wise would rarely be found wanting among large bodies of men; that he had heard it was so in workhouses, in the police force, even in that last desperate resource, the army; and that he knew it was so, more or less, in any great railway staff. He had been, when young (if I could believe it, sitting in that, hut; he scarcely could), a student of natural philosophy, and had attended lectures; but he had run wild, misused his opportunities, gone down, and never risen again. He had no complaint to offer about that. He had made his bed and he lay upon it. It was far too late to make another.

All that I have here condensed, he said in a quiet manner, with his grave dark regards divided between me and the fire. He threw in the word ‘Sir’ from time to time, and especially when he referred to his youth: as though to request me to understand that he claimed to be nothing but what I found him. He was several times interrupted by the little bell, and had to read off messages, and send replies. Once, he had to stand without the door, and display a flag as a train passed, and make some verbal communication to the driver. In the discharge of his duties I observed him to be remarkably exact and vigilant, breaking off his discourse at a syllable, and remaining silent until what he had to do was done.

In a word, I should have set this man down as one of the safest of men to be employed in that capacity, but for the circumstance that while he was speaking to me he twice broke off with a fallen colour, turned his face towards the little bell when it did NOT ring, opened the door of the hut (which was kept shut to exclude the unhealthy damp), and looked out towards the red light near the mouth of the tunnel. On both of those occasions, he came back to the fire with the inexplicable air upon him which I had remarked, without being able to define, when we were so far asunder.

Said I when I rose to leave him: ‘You almost make me think that I have met with a contented man.’

(I am afraid I must acknowledge that I said it to lead him on.)

‘I believe I used to be so,’ he rejoined, in the low voice in which he had first spoken; ‘but I am troubled, sir, I am troubled.’

He would have recalled the words if he could. He had said them, however, and I took them up quickly.

‘With what? What is your trouble?’

‘It is very difficult to impart, sir. It is very, very difficult to speak of. If ever you make me another visit, I will try to tell you.’

‘But I expressly intend to make you another visit. Say, when shall it be?’

‘I go off early in the morning, and I shall be on again at ten to-morrow night, sir.’

‘I will come at eleven.’

He thanked me, and went out at the door with me.

‘I’ll show my white light, sir,’ he said, in his peculiar low voice, ’till you have found the way up. When you have found it, don’t call out! And when you are at the top, don’t call out!’

His manner seemed to make the place strike colder to me, but I said no more than ‘Very well.’

‘And when you come down to-morrow night, don’t call out! Let me ask you a parting question. What made you cry ‘Halloa! Below there!’ to-night?’

‘Heaven knows,’ said I. ‘I cried something to that effect—-‘

‘Not to that effect, sir. Those were the very words. I know them well.’

‘Admit those were the very words. I said them, no doubt, because I saw you below.’

‘For no other reason?’

‘What other reason could I possibly have!’

‘You had no feeling that they were conveyed to you in any supernatural way?’

‘No.’

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very disagreeable sensation of a train coming behind me), until I found the path. It was easier to mount than to descend, and I got back to my inn without any adventure.

Punctual to my appointment, I placed my foot on the first notch of the zig-zag next night, as the distant clocks were striking eleven. He was waiting for me at the bottom, with his white light on. ‘I have not called out,’ I said, when we came close together; ‘may I speak now?’ ‘By all means, sir.’ ‘Good night then, and here’s my hand.’ ‘Good night, sir, and here’s mine.’ With that, we walked side by side to his box, entered it, closed the door, and sat down by the fire.

‘I have made up my mind, sir,’ he began, bending forward as soon as we were seated, and speaking in a tone but a little above a whisper, ‘that you shall not have to ask me twice what troubles me. I took you for someone else yesterday evening. That troubles me.’

‘That mistake?’

‘No. That someone else.’

‘Who is it?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Like me?’

‘I don’t know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face, and the right arm is waved. Violently waved. This way.’

I followed his action with my eyes, and it was the action of an arm gesticulating with the utmost passion and vehemence: ‘For God’s sake clear the way!’

‘One moonlight night,’ said the man, ‘I was sitting here, when I heard a voice cry “Halloa! Below there!” I started up, looked from that door, and saw this Some one else standing by the red light near the tunnel, waving as I just now showed you. The voice seemed hoarse with shouting, and it cried, “Look out! Look out!” And then again “Halloa! Below there! Look out!” I caught up my lamp, turned it on red, and ran towards the figure, calling, “What’s wrong? What has happened? Where?” It stood just outside the blackness of the tunnel. I advanced so close upon it that I wondered at its keeping the sleeve across its eyes. I ran right up at it, and had my hand stretched out to pull the sleeve away, when it was gone.’

‘Into the tunnel,’ said I.

‘No. I ran on into the tunnel, five hundred yards. I stopped and held my lamp above my head, and saw the figures of the measured distance, and saw the wet stains stealing down the walls and trickling through the arch. I ran out again, faster than I had run in (for I had a mortal abhorrence of the place upon me), and I looked all round the red light with my own red light, and I went up the iron ladder to the gallery atop of it, and I came down again, and ran back here. I telegraphed both ways, “An alarm has been given. Is anything wrong?” The answer came back, both ways: “All well.”‘

Resisting the slow touch of a frozen finger tracing out my spine, I showed him how that this figure must be a deception of his sense of sight, and how that figures, originating in disease of the delicate nerves that minister to the functions of the eye, were known to have often troubled patients, some of whom had become conscious of the nature of their affliction, and had even proved it by experiments upon themselves. ‘As to an imaginary cry,’ said I, ‘do but listen for a moment to the wind in this unnatural valley while we speak so low, and to the wild harp it makes of the telegraph wires!’

That was all very well, he returned, after we had sat listening for a while, and he ought to know something of the wind and the wires, he who so often passed long winter nights there, alone and watching. But he would beg to remark that he had not finished.

I asked his pardon, and he slowly added these words, touching my arm: ‘Within six hours after the Appearance, the memorable accident on this Line happened, and within ten hours the dead and wounded were brought along through the tunnel over the spot where the figure had stood.’

A disagreeable shudder crept over me, but I did my best against it. It was not to be denied, I rejoined, that this was a remarkable coincidence, calculated deeply to impress his mind. But it was unquestionable that remarkable coincidences did continually occur, and they must be taken into account in dealing with such a subject. Though to be sure I must admit, I added (for I thought I saw that he was going to bring the objection to bear upon me), men of common sense did not allow much for coincidences in making the ordinary calculations of life.

He again begged to remark that he had not finished.

I again begged his pardon for being betrayed into interruptions.

‘This,’ he said, again laying his hand upon my arm, and glancing over his shoulder with hollow eyes, ‘was just a year ago. Six or seven months passed, and I had recovered from the surprise and shock, when one morning, as the day was breaking, I, standing at that door, looked towards the red light, and saw the spectre again.’ He stopped, with a fixed look at me.

‘Did it cry out?’

‘No. It was silent.’

‘Did it wave its arm?’

‘No. It leaned against the shaft of the light, with both hands before the face. Like this.’

Once more, I followed his action with my eyes. It was an action of mourning. I have seen such an attitude in stone figures on tombs.

‘Did you go up to it?’

‘I came in and sat down, partly to collect my thoughts, partly because it had turned me faint. When I went to the door again, daylight was above me, and the ghost was gone.’

‘But nothing followed? Nothing came of this?’

He touched me on the arm with his forefinger twice or thrice, giving a ghastly nod each time: ‘That very day, as a train came out of the tunnel, I noticed, at a carriage window on my side, what looked like a confusion of hands and heads, and something waved. I saw it, just in time to signal the driver, Stop! He shut off, and put his brake on, but the train drifted past here a hundred and fifty yards or more. I ran after it, and, as I went along, heard terrible screams and cries. A beautiful young lady had died instantaneously in one of the compartments, and was brought in here, and laid down on this floor between us.’

Involuntarily, I pushed my chair back, as I looked from the boards at which he pointed, to himself.

‘True, sir. True. Precisely as it happened, so I tell it you.’

I could think of nothing to say, to any purpose, and my mouth was very dry. The wind and the wires took up the story with a long lamenting wail.

He resumed. ‘Now, sir, mark this, and judge how my mind is troubled. The spectre came back, a week ago. Ever since, it has been there, now and again, by fits and starts.’

‘At the light?’

‘At the Danger-light.’

‘What does it seem to do?’

He repeated, if possible with increased passion and vehemence, that former gesticulation of ‘For God’s sake clear the way!’

Then, he went on. ‘I have no peace or rest for it. It calls to me, for many minutes together, in an agonised manner, “Below there! Look out! Look out!” It stands waving to me. It rings my little bell—-‘

I caught at that. ‘Did it ring your bell yesterday evening when I was here, and you went to the door?’

‘Twice.’

‘Why, see,’ said I, ‘how your imagination misleads you. My eyes were on the bell, and my ears were open to the bell, and if I am a living man, it did NOT ring at those times. No, nor at any other time, except when it was rung in the natural course of physical things by the station communicating with you.’

He shook his head. ‘I have never made a mistake as to that, yet, sir. I have never confused the spectre’s ring with the man’s. The ghost’s ring is a strange vibration in the bell that it derives from nothing else, and I have not asserted that the bell stirs to the eye. I don’t wonder that you failed to hear it. But I heard it.’

‘And did the spectre seem to be there, when you looked out?’

‘It WAS there.’

‘Both times?’

He repeated firmly: ‘Both times.’

‘Will you come to the door with me, and look for it now?’

He bit his under-lip as though he were somewhat unwilling, but arose. I opened the door, and stood on the step, while he stood in the doorway. There, was the Danger-light. There, was the dismal mouth of the tunnel. There, were the high wet stone walls of the cutting. There, were the stars above them.

‘Do you see it?’ I asked him, taking particular note of his face. His eyes were prominent and strained; but not very much more so, perhaps, than my own had been when I had directed them earnestly towards the same spot.

‘No,’ he answered. ‘It is not there.’

‘Agreed,’ said I.

We went in again, shut the door, and resumed our seats. I was thinking how best to improve this advantage, if it might be called one, when he took up the conversation in such a matter of course way, so assuming that there could be no serious question of fact between us, that I felt myself placed in the weakest of positions.

‘By this time you will fully understand, sir,’ he said, ‘that what troubles me so dreadfully, is the question, What does the spectre mean?’

I was not sure, I told him, that I did fully understand.

‘What is its warning against?’ he said, ruminating, with his eyes on the fire, and only by times turning them on me. ‘What is the danger? Where is the danger? There is danger overhanging, somewhere on the Line. Some dreadful calamity will happen. It is not to be doubted this third time, after what has gone before. But surely this is a cruel haunting of me. What can I do?’

He pulled out his handkerchief, and wiped the drops from his heated forehead.

‘If I telegraph Danger, on either side of me, or on both, I can give no reason for it,’ he went on, wiping the palms of his hands. ‘I should get into trouble, and do no good. They would think I was mad. This is the way it would work:–Message: “Danger! Take care!” Answer: “What danger? Where?” Message: “Don’t know. But for God’s sake take care!” They would displace me. What else could they do?’

His pain of mind was most pitiable to see. It was the mental torture of a conscientious man, oppressed beyond endurance by an unintelligible responsibility involving life.

‘When it first stood under the Danger-light,’ he went on, putting his dark hair back from his head, and drawing his hands outward across and across his temples in an extremity of feverish distress, ‘why not tell me where that accident was to happen–if it must happen? Why not tell me how it could be averted–if it could have been averted? When on its second coming it hid its face, why not tell me instead: “She is going to die. Let them keep her at home”? If it came, on those two occasions, only to show me that its warnings were true, and so to prepare me for the third, why not warn me plainly now? And I, Lord help me! A mere poor signalman on this solitary station! Why not go to somebody with credit to be believed, and power to act!’

When I saw him in this state, I saw that for the poor man’s sake, as well as for the public safety, what I had to do for the time was, to compose his mind. Therefore, setting aside all question of reality or unreality between us, I represented to him that whoever thoroughly discharged his duty, must do well, and that at least it was his comfort that he understood his duty, though he did not understand these confounding Appearances. In this effort I succeeded far better than in the attempt to reason him out of his conviction. He became calm; the occupations incidental to his post as the night advanced, began to make larger demands on his attention; and I left him at two in the morning. I had offered to stay through the night, but he would not hear of it.

That I more than once looked back at the red light as I ascended the pathway, that I did not like the red light, and that I should have slept but poorly if my bed had been under it, I see no reason to conceal. Nor, did I like the two sequences of the accident and the dead girl. I see no reason to conceal that, either.

But, what ran most in my thoughts was the consideration how ought I to act, having become the recipient of this disclosure? I had proved the man to be intelligent, vigilant, painstaking, and exact; but how long might he remain so, in his state of mind? Though in a subordinate position, still he held a most important trust, and would I (for instance) like to stake my own life on the chances of his continuing to execute it with precision?

Unable to overcome a feeling that there would be something treacherous in my communicating what he had told me, to his superiors in the Company, without first being plain with himself and proposing a middle course to him, I ultimately resolved to offer to accompany him (otherwise keeping his secret for the present) to the wisest medical practitioner we could hear of in those parts, and to take his opinion. A change in his time of duty would come round next night, he had apprised me, and he would be off an hour or two after sunrise, and on again soon after sunset. I had appointed to return accordingly.

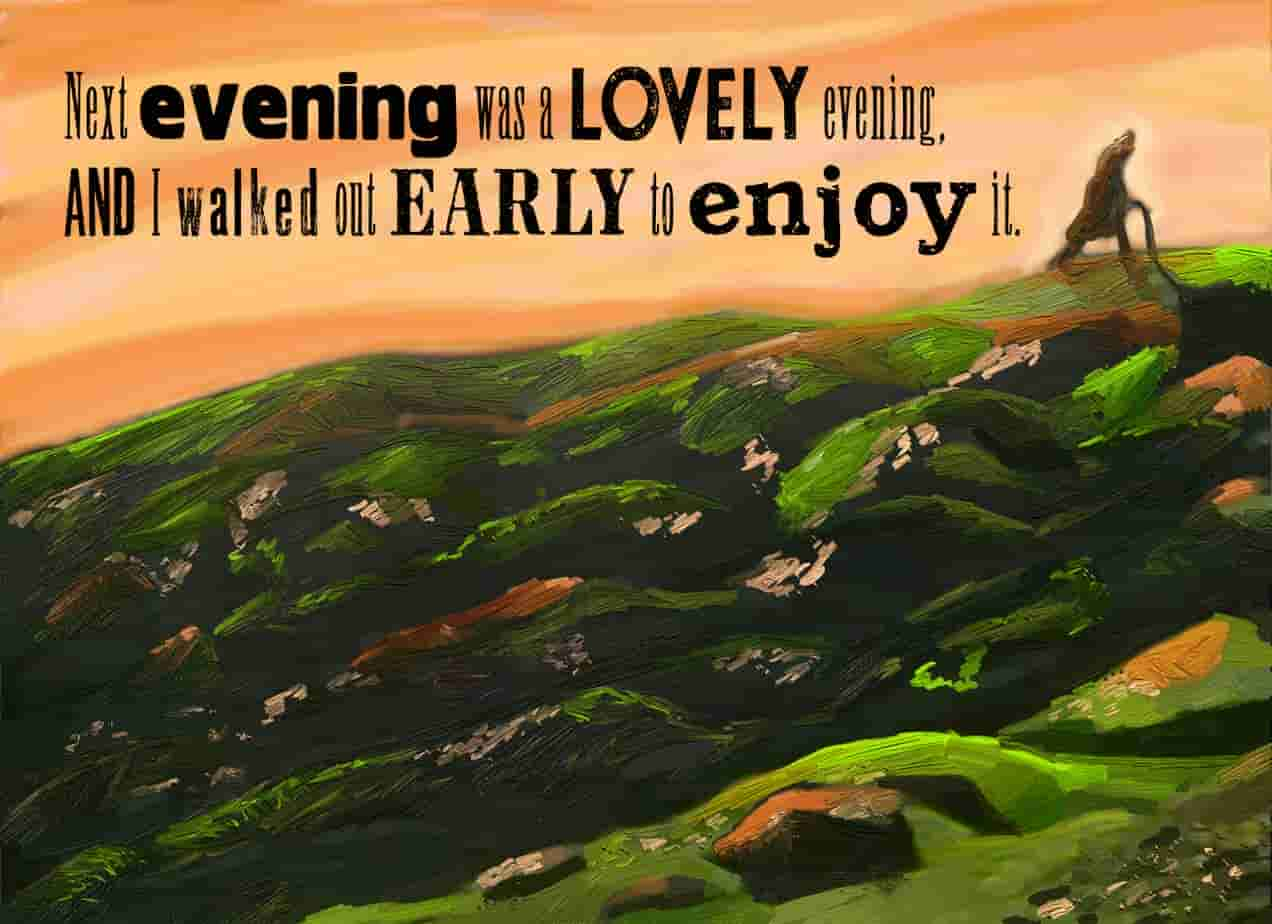

Next evening was a lovely evening, and I walked out early to enjoy it. The sun was not yet quite down when I traversed the field-path near the top of the deep cutting. I would extend my walk for an hour, I said to myself, half an hour on and half an hour back, and it would then be time to go to my signalman’s box.

The narrator gives no thought to this man perhaps having a family life. For the narrator, he lives down here 24 hours a day, so very alone that he pretty much invents his own language.

Clearly the narrator has been chatting to this guy at length and has come up with a synopsis of his entire life. But why would the signalman necessarily talk to a random dude walking by about anything other than his job? This story has me wondering if, in the mid 1800s, with nothing much for entertainment, people were in the habit of going out for strolls, meeting someone doing their work, then hanging out with them for the evening. Health and safety measures dictate that we no longer bother people trying to do their work. But maybe this was a thing? Like, see you later this evening my love, I’m off to hang out with the local signalman!

In the 1976 television adaptation, the signalman speaks with a working class accent and the narrator with an educated accent. This is the part which gives this away.

Again, Dickens’ narrator assumes the job of signalman wouldn’t benefit from education. Yet he’s a little self-conscious in saying this, so he’s clearly aware of his snobbery (or Dickens is).

This may sound like something out of the 1800s, but in the mid 00s I found a temp job in a basement in London. If the pay had been better I’d have loved it. I worked with one older guy who had emigrated when young the Dominican Republic and worked for a while as a bus conductor. He made us listen to the church radio station, until I bought in some Louis Armstrong, which he loved. He told me he’d been good at maths when young and squandered his talent. Now he’d spent the bulk of his working life sorting mail in a basement for six quid an hour.

That was a lot of words to tell us, “This guy may have had a no brainer job, but he was pretty fucken far from crazy.”

If there’s one thing creepier than a mechanical bell ringin out in the night it’s a mechanical bell not ringin out when you’re expecting it to.

There’s a clear palette to this story: the desaturation of night with red and oranges as accent colour. First the red light, now the fire.

Again, the narrator can’t quite ‘define’ this ‘inexplicable’ event drawing him to this random railway worker.

Dickens’ background editing a journal comes to the fore here. Or perhaps this is the mark of any storyteller.

‘Rejoined’ is one of Dickens’ favourite words, but it stands out if modern writers use it.

This trick, in which a character is unable to express something supernatural until they’ve had time to think about it, is a useful way to draw out suspense but is a cosmic horror trick which doesn’t work for contemporary readers (unless it’s a spoof).

For us, ‘witching hour’ is midnight, but for earlier audiences, this magical period occurred between 9pm and 3am.

Later we learn that the ghost also uses the same greeting. Is this a coincidence? Or is this a circle of life kind of thing? The narrator as ghost because death is coming to us all, and we should all therefore start thinking about our relationships with those on the Other Side.

I’d be inclined to start this paragraph with ‘Next night…’ to let readers know immediately that there’s been a gap in the time. Not Dickens, though. He plonks it mid-sentence. The clocks striking eleven provide a soundtrack to the story, along with the sound of the signalman’s bells and the oncoming steam train.

No! Don’t do it! Don’t run into a tunnel, ever! Especially if you suspect ghosts, dammit! Wet stains, too? Trickling down the walls? OMG. (See the film Dark Water for excellent trickling water horror, the Japanese version if you can.)

Writers of children’s books must lampshade why kids don’t tell adults about their problems. Likewise, writers of supernatural fiction lampshade why adult characters don’t bother telling other adults about their visions and it is usually this: “No one would believe me anyway.”

This narrator is one of those annoying guys who uses logic to explain everything. The logic and stats guys usually get their comeuppance. I’m a fan of scientific literacy, but some people refuse to believe lived experience unless there are stats and figures to back it up. This endures until they themselves have a lived experience. Eye roll.

The rest of this paragraph suggests this narrator is a doctor, or medical adjacent. Or fancies himself a doctor. We all know many of those in these times of social media and plague.

“This unnatural valley” is an interesting description of the manmade cutting of the railway line, playing on a collective fear that by utilising life-changing tech, we are interfering with the will of God. This is the Industrial Revolution, after all. Previously quiet towns now had these noisy, deadly machines punctuating the quietude. Train tracks make an excellent setting for a scary story.

Is there significance to the numbers six and ten? Six is a multiple of three, which is important in witchcraft. In the Bible, the sixth day happens right before the day of rest (here, eternal rest?) Maybe I’m stretching. The number ten is clearly significant to humans because of ten digits on each hand, meaning perfection (in the ‘complete’ sense).

When making use of coincidence, writers will often point it out via their narrator to pre-empt the same question in the mind of the readers, and to keep readers in the story.

The story is an allegory for Charles Dickens’ own PTSD after his own train accident. Of course, the diagnosis didn’t exist back then, there was no counselling (except perhaps from the clergy) and in any case, men were expected to be stoic.

What is it about being touched with a forefinger which is so very different from being touched with the entirety of the palm? One is accusatory, the other comforting. In any case, we associate the prod strongly with the touch of ghosts.

We are still collectively captivated by the murder of ‘beautiful young’ (white) ladies, in fiction and in the media. Society both objectifies and valorises this demographic of person when she dies, which is simply a different take on what beautiful young women experience while alive.

When the narrator ‘involuntarily’ pushes his chair back he experiences some kind of revelation. Ghosts might be real after all.

Pathetic fallacy of the auditory kind.

He is seeing the Grim Reaper, of course. This is a slightly different take on Mr Reaper, as he’s not dressed in black, nor is he carrying a scythe. This is the horror-railway version for modern audiences of the 1860s Industrial Revolution. This Grim Reaper is using modern technology of the day to warn the signalman of his own impending death. These days we call this trope Ghost in the Machine.

The signalman is using his sixth sense to detect the ghost ringing the bell. The most logic driven guy can’t really argue with someone who is using their sixth sense. But this logic driven narrator has been getting the heebie jeebies for a while now. He’s primed to hook into this other realm himself. Now he might see if he only looks, like some Magic Eye illustration.

“Dismal mouth of the tunnel”. We commonly talk about the mouths of tunnels, so it’s easy to forget that this is a cannibalistic example of personification.

That was what we’d now call a jump scare.

The narrator is now sure that he doesn’t know everything after all, and that not everything can be worked out via his powers of deduction.

Humans are primed to interpret unexplained phenomena as warnings. This has served us well throughout evolution. It’s perfectly possible, of course, that a phenomenon simply is; no apotropaic purpose intended. In ghost stories, however, spectres do tend to have a purpose. Otherwise the ghost story is a bit of a flop. (Opponents need to have their own desires and plans.) Occasionally (especially in a kids’ story) you get a ghost who is simply hanging around minding its own business but this is a subversion on the Dickensian ghost story.

“Wiped the drops from his heated forehead” manages to combine both the damp dripping down the walls of the tunnel and also the red heat of the (hell)fire and the death-light. If reading this story symbolically, this is the part where we know this guy is dead meat.

In psychological horror others commonly think the person who sees the ghost is mad or crazy. These characters are generally disempowered in some way. Often they’re not believed because they’re young and female. In this case, the signalman does not have a powerful status and he is also a night-worker. I’m guessing night-workers are lower status again, if only because their assumed tiredness would make them less reliable as witness.

Here Dickens shows empathy from the narrator.

These questions relate at a surface level to the spectre in this story, but speak to more general existential* matters. If ghosts give us warnings, why not be more specific, dammit? Either tell me the whole story or none at all. This speaks to Dickens’ view of how we ascribe apotropaic powers to strange phenomena. The same frustration can be applied to notions of an interventionist God: If you’re looking out for me, Big Fella, why not really look out for me? Why all this half-arsed fiddle-fannying about, dropping hints and tests but never stepping in when I need you most?

Compose the signalman’s mind, or his own?

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Dickens’ train crash was due to some work on the railway line remaining incomplete. A signalman and/or linesmen had not done their job. Dickens must have reflected on how reliant we all are on other people doing their jobs properly. Contemporary readers are used to this, but as people entered the Industrial Revolution, powered by machines they did not understand and did not own, this must have been a common fear.

The narrator sort of does believe the ghost story, but also kind of doesn’t. Now he wants the advice of a medical man.

“My” signalman now.

Before pursuing my stroll, I stepped to the brink, and mechanically looked down, from the point from which I had first seen him. I cannot describe the thrill that seized upon me, when, close at the mouth of the tunnel, I saw the appearance of a man, with his left sleeve across his eyes, passionately waving his right arm.

The nameless horror that oppressed me, passed in a moment, for in a moment I saw that this appearance of a man was a man indeed, and that there was a little group of other men standing at a short distance, to whom he seemed to be rehearsing the gesture he made. The Danger-light was not yet lighted. Against its shaft, a little low hut, entirely new to me, had been made of some wooden supports and tarpaulin. It looked no bigger than a bed.

With an irresistible sense that something was wrong–with a flashing self-reproachful fear that fatal mischief had come of my leaving the man there, and causing no one to be sent to overlook or correct what he did–I descended the notched path with all the speed I could make.

‘What is the matter?’ I asked the men.

‘Signalman killed this morning, sir.’

‘Not the man belonging to that box?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Not the man I know?’

‘You will recognise him, sir, if you knew him,’ said the man who spoke for the others, solemnly uncovering his own head and raising an end of the tarpaulin, ‘for his face is quite composed.’

‘O! how did this happen, how did this happen?’ I asked, turning from one to another as the hut closed in again.

‘He was cut down by an engine, sir. No man in England knew his work better. But somehow he was not clear of the outer rail. It was just at broad day. He had struck the light, and had the lamp in his hand. As the engine came out of the tunnel, his back was towards her, and she cut him down. That man drove her, and was showing how it happened. Show the gentleman, Tom.’

The man, who wore a rough dark dress, stepped back to his former place at the mouth of the tunnel!

‘Coming round the curve in the tunnel, sir,’ he said, ‘I saw him at the end, like as if I saw him down a perspective-glass. There was no time to check speed, and I knew him to be very careful. As he didn’t seem to take heed of the whistle, I shut it off when we were running down upon him, and called to him as loud as I could call.’

‘What did you say?’

‘I said, Below there! Look out! Look out! For God’s sake clear the way!’

I started.

‘Ah! it was a dreadful time, sir. I never left off calling to him. I put this arm before my eyes, not to see, and I waved this arm to the last; but it was no use.’

Without prolonging the narrative to dwell on any one of its curious circumstances more than on any other, I may, in closing it, point out the coincidence that the warning of the Engine-Driver included, not only the words which the unfortunate Signalman had repeated to me as haunting him, but also the words which I myself–not he–had attached, and that only in my own mind, to the gesticulation he had imitated.

The narrator relates his tale as though he were no longer in full control of events. ‘Mechanically’, ‘seized upon me’. Dickens is tricking us here, though not for long. In the following paragraph we learn it’s not a ghost he has seen but a real man. This momentary lull in supernatural events makes the reveal more thrilling.

Now it is confirmed by a third party that the signalman killed was definitely not a madman. Dickens takes us back to the beginning of the story, in which the narrator calls to the signalman and the signalman is facing the wrong way. This is how the spectre gets him.

A perspective glass is also called a zograscope or a vue d’optique and was used by mapmakers. It’s basically a tabletop magnifying glass/mirror combo on a stand. The magnifying lens allows mapmakers to see a map placed on the table and the mirror reverses this image.

Together, the magnification and reflection created an illusion of greater distance from the image, and the curved lens made the center of the image appear farther away than the edges. These optical effects lent depth and realism to the image, giving the viewer a sense of immersion in the depicted scene.

The McAllister Perspective Glass: A Lens on 19th-Century Optical Entertainments

The description of the perspective glass tells us something about the themes of this story. Although the story predates Modernism by quite a bit, the Modernists were interested in how there’s no such thing as ‘reality’, it all depends on your perspective. Reality actually changes depending on where you view it from. In the context of a ghost story, the slipperiness of ‘realness’ can apply to anything, even to supernatural phenomena. Even if it’s not real, the experience is real to whoever bears witness.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The Missouri-Pacific Railroad Depot-Gurdon is a historic railroad station building at North 1st Street and East Walnut Street in Gurdon, Arkansas.

The area is thought to be haunted. Look in the swampy woods near the town of Gurdon.

Gurdon, Arkansas is located about 75 miles south of Little Rock on Interstate 30 and is located just east of the Interstate on Highway 67. The light is outside of town and along a stretch of railroad tracks. It takes a couple of hours to reach the location. You can ask for directions in Gurdon. Ask at any gas station. Everyone in this small town knows what you mean (they call it “ghost light bluffs”). There is a similar light with a similar story in Crossett. Crossett has lots of quartz too.

Trip Savvy

For almost ninety years people have been seeing there a glowing orb that is said to be a ghost of a railroad foreman that was killed at this spot in 1931.

The art in this post was inspired by screenshots from the 1976 short film. Bear in mind that the film sets the story in the 1900s, whereas the story is set in the 1860s. You can see this in the clothing if you’ve made a study of fashions over time.