I’ve been meaning to take a closer look at the picture books of Australian Shaun Tan for a long time. But when I sit down to do just that, in the face of Tan’s work I sometimes draw a blank. This is odd for me, who can generally knock out a few thousand words on a picture book no problem. Why do I lose words when it comes to Shaun Tan? Perhaps because there’s nothing more to be said? His pictures and text says it all?

Surely not! If I’m reluctant to delve into Tan’s work, that’s probably because whatever I say, it doesn’t make a dent in all that can be said.

If The Lost Thing makes you question, The Red Tree make you feel, and The Arrival make you empathize, then Tales from Outer Suburbia should make you think.

The Book Wars

Tales From Outer Suburbia is a collection of various stories. Some are published independently e.g. Eric, which exists as a miniature stand-alone book. (I’ve previously written about Eric here.) The common thread between stories in this compendium: All stories are set in the same, off-kilter suburb. Some of the stories have no words, and might consist only of a single frame of narrative art. Creative Arts teachers find this really useful in the classroom because these images can ostensibly work as story starters, though I do wonder if students might experience the same awe as I do when confronted with these pieces, unable to come up with anything at all!

The Academy Award-winning team behind The Lost Thing, Shaun Tan and producer Sophie Byrne (Highly Spirited), has joined forces with Barbara Stephen and Alexia Gates-Foale from award-winning animation studio Flying Bark Productions to develop an animated series based on Tan’s bestselling illustrated book Tales from Outer Suburbia.

Flying Bark Adapting Oscar Winner Shaun Tan’s ‘Tales from Outer Suburbia’ to Series (August 2022)

CREATIVE LEARNING IDEAS: ART OF YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD

- Using “The Water Buffalo” as mentor text, students write a story about a wild creature they find somewhere in their house, yard or street.

- Find something around your house which is old or dilapidated or broken and make a still life sketch of it a la “Broken Toys”.

- Using “Distant Rains”, and an opening that goes: “Have you every wondered what happens to [X]” students create a poster sized collage using scraps of paper from around the classroom and house.

- Also using images from “Distant Rains”, students use a Google Maps or Google Street View aerial shot of their suburb to recreate the double page spread using dark pencil, turning a daytime view into night. Insert a creature into an aerial shot of a house/suburb, a la the dugong on the front lawn in “Undertow”.

- Online art teacher Aaron Blaise sells a lesson which teaches you how to create creatures out of clouds. Requires Photoshop or Affinity Photo, but could be adapted for open source GIMP. (I suggest this course because results remind me of Shaun Tan Surrealism.)

- If students have Google Drive (with space to spare and access to good, modern computers), they can use a free AI art generator such as Disco Diffusion to create Shaun Tan-esque images of their own. These can be used as a base for creating realworld artworks, or as prompts for their own stories.

This short YouTube video should be enough to get students started.

SUBURBAN SETTINGS IN STORYTELLING

THE CHANGING NATURE OF SUBURBIA

When I think ‘suburbs’ today, I think of an outlying residential district of a city, but one where residents aren’t necessarily connected other than by coincidence of proximity. At the beginning of the 20th century, people’s perception and experience of suburbia looked a little different.

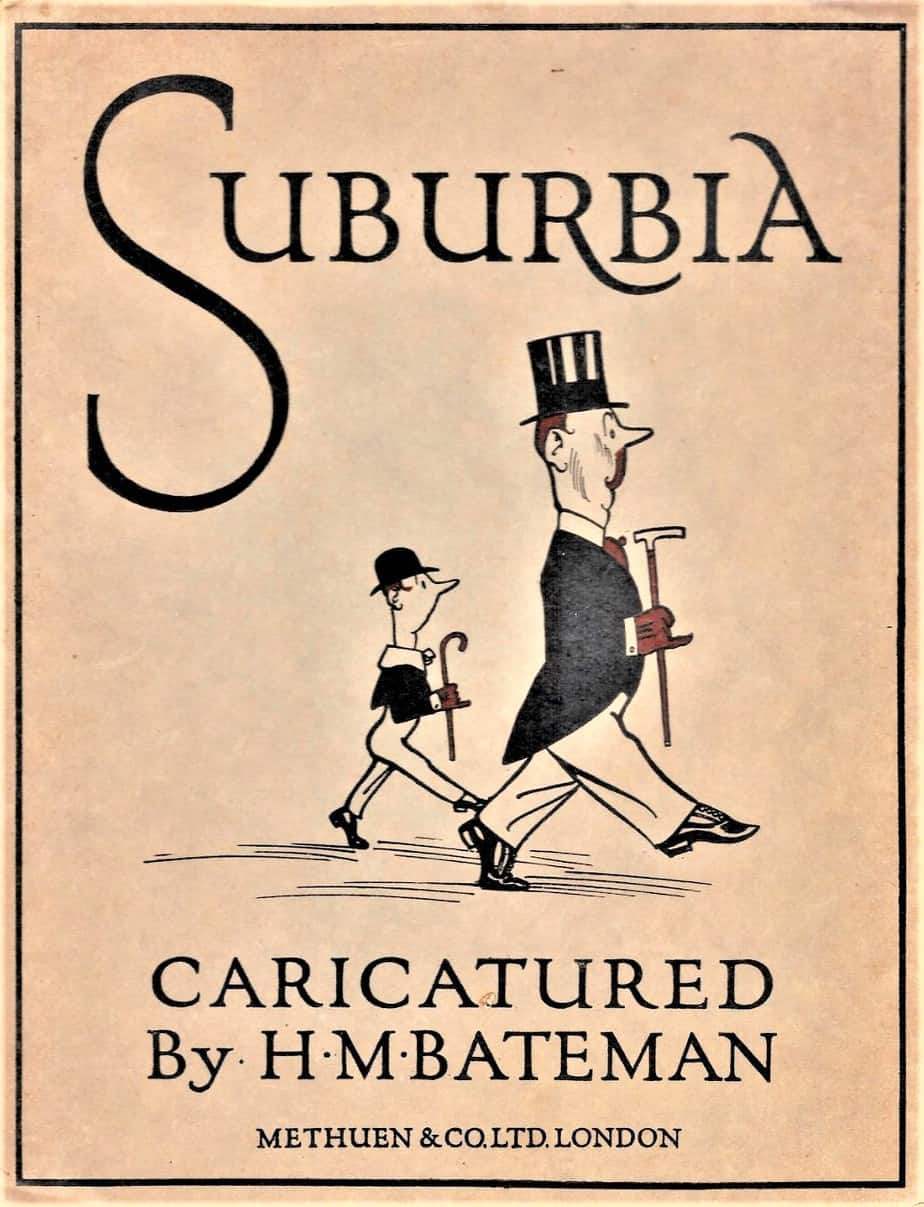

This short book of captioned caricatures and cartoons appeared in 1922. Much of the humour will be lost on a modern audience (or on me, at least) and suburbia of the 1920s looked quite different from today’s suburbia, more akin to a rural village, where everybody knows everybody. Cars have changed the meaning and experience of suburbia, as people no longer tend to live their lives there, travelling to and from a nearby city, or to another suburb, for work, and for a chance at ‘better’ schooling.

SHAUN TAN’S SUBURBIA

Which suburbs influenced Shaun Tan? Well, Tan grew up in the northern suburbs of Perth, Western Australia.

[Tan] gives more weight to living in Hillarys, a far-flung coastal suburb of Perth [than to his Chinese Malaysian heritage] — “not quite as bland as the pastel suburbia of Edward Scissorhands but not too far from it either”. Now more urban but then very much on the city’s periphery, Hillarys supplies the atmosphere that pervades two of Tan’s more recent books, Tales from Outer Suburbia (2008) and Rules of Summer (2013). The feeling they convey is one of nature pushed back unceremoniously but incompletely; of freeways and cul-de-sacs freshly bulldozed from a bush that “rolled and twisted like an unmade bed”. (Tim Winton, the novelist whose line this is, spent his boyhood in nearby Karrinyup, and was read voraciously by Tan when he was a teenager.)

Financial Times

THE SUBURBS AND AMERICA

Let’s talk about suburbs in storytelling more generally. I tend to associate suburbs with America, as I associate the Road Trip story with America. Both types of story are equally relevant to Australia, but the United States feels like the home of both genres.

Stories set in suburbs have an intimate connection to road stories, not least because the development of America’s highway network led directly to the proliferation of suburbs. This happened in the middle of the 20th century. In the space of about 20 years, the majority Americans migrated in to suburbs. In the 1950s alone, 19 million Americans moved to the suburbs surrounding the six major cities.

Suburbs became the theatre stage of social conformity and hives of social interaction. In this context, ‘theatre’ refers to a ‘safe’ setting where things play out predictably, in contrast to the wilderness. Artists and storytellers have been working ever since to remind us that there is no escaping the harsh realities of life, not even for white people wealthy enough to buy a home in the suburbs. The creation of suburbia has always been a method of making the rich richer and the poor poorer. In the mid-20th century, U.S. highway planners sometimes purposefully destroyed Black communities by routing highways through them.

AUSTRALIAN SUBURBS

Here in Australia, planners continue to destroy land and trees with Aboriginal significance, prioritising the convenience of arterial routes for the masses.

The Victorian government has cut down a tree that was culturally significant to Australia’s Indigenous Djab Wurrung women to make way for a highway in the state’s west.

‘Chainsaws tearing through my heart’: 50 arrested as sacred tree cut down to make way for Victorian highway

Suburbia is where the developer bulldozes out the trees, then names the streets after them.

Bill Vaughan

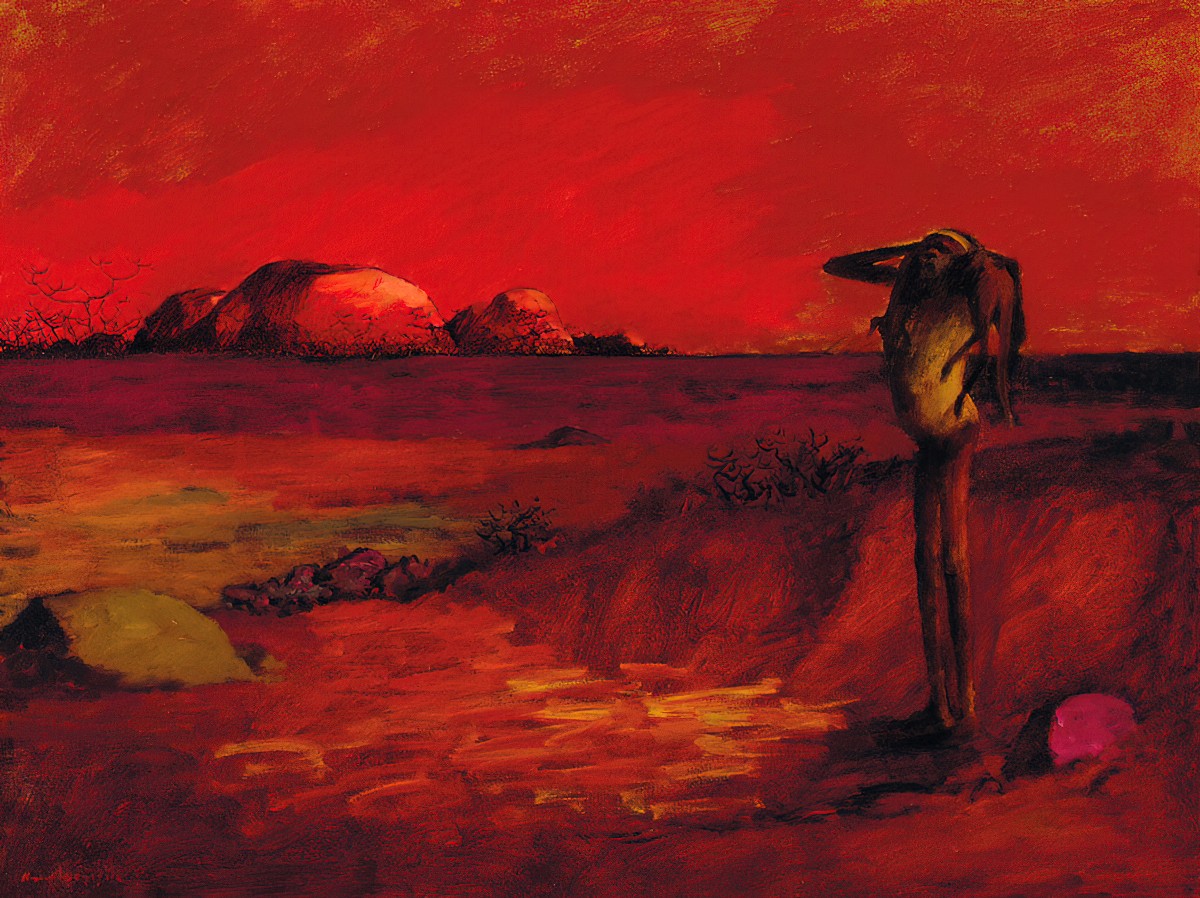

Are Shaun Tan’s suburbs have distinctively Australian? I’m probably not in the best position to tell. However, the frontispiece of Tales From Outer Suburbia is a double spread, high angle view of a street with a definite reddish cast, which may be a simple fact of sunset, but this redness is also a feature of the Australian landscape. Grass on the verge looks mostly dead despite being hand-watered by a man holding a hose. A man hand-watering his lawn is a feature of Australian summer with lowered water restriction. (Sprinklers are pretty much always banned everywhere now, and even when they’re not banned, the culture has moved away from them.)

THE EERINESS INHERENT TO SUBURBIA

Suburbs have an eeriness about them, especially as they emerge. Before greenery has a chance to grow, the houses look same-same but not quite the same at all. (This technique has been used for centuries by artists aiming to create a sense of the uncanny.)

SUBURBS AS DEATH

These days, if you encounter a story set in the suburbs, chances are it won’t end well for the characters:

Happy endings are famously rare in literature. We turn to great books for emotional and ethical complexity, and broad-scale resolution cheats our sense of what real life is like. Because complex problems rarely resolve completely, the best books tend to haunt and unnerve readers even as they edify and entertain.

This is especially true in writing about the suburbs, perhaps because that setting has served as a symbolic happy ending to the broader American cultural narrative. It’s no accident that the best-known stories about the upper middle class—books like John Updike’s Rabbit, Run; Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road; Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm, to name a few, and films like American Beauty—tend to have exceptionally brutal finales. These works, in their final moments, devastate and eviscerate their characters—and with them the notion that suburban living is the proper happy ending for the American life.

The Atlantic, How To Write A Believable Happy Ending

Speaking of The Ice Storm movie adaptation (1999), I didn’t understand the plot. Later I realised Tobey Maguire and Elijah Wood are meant to be two separate dudes.

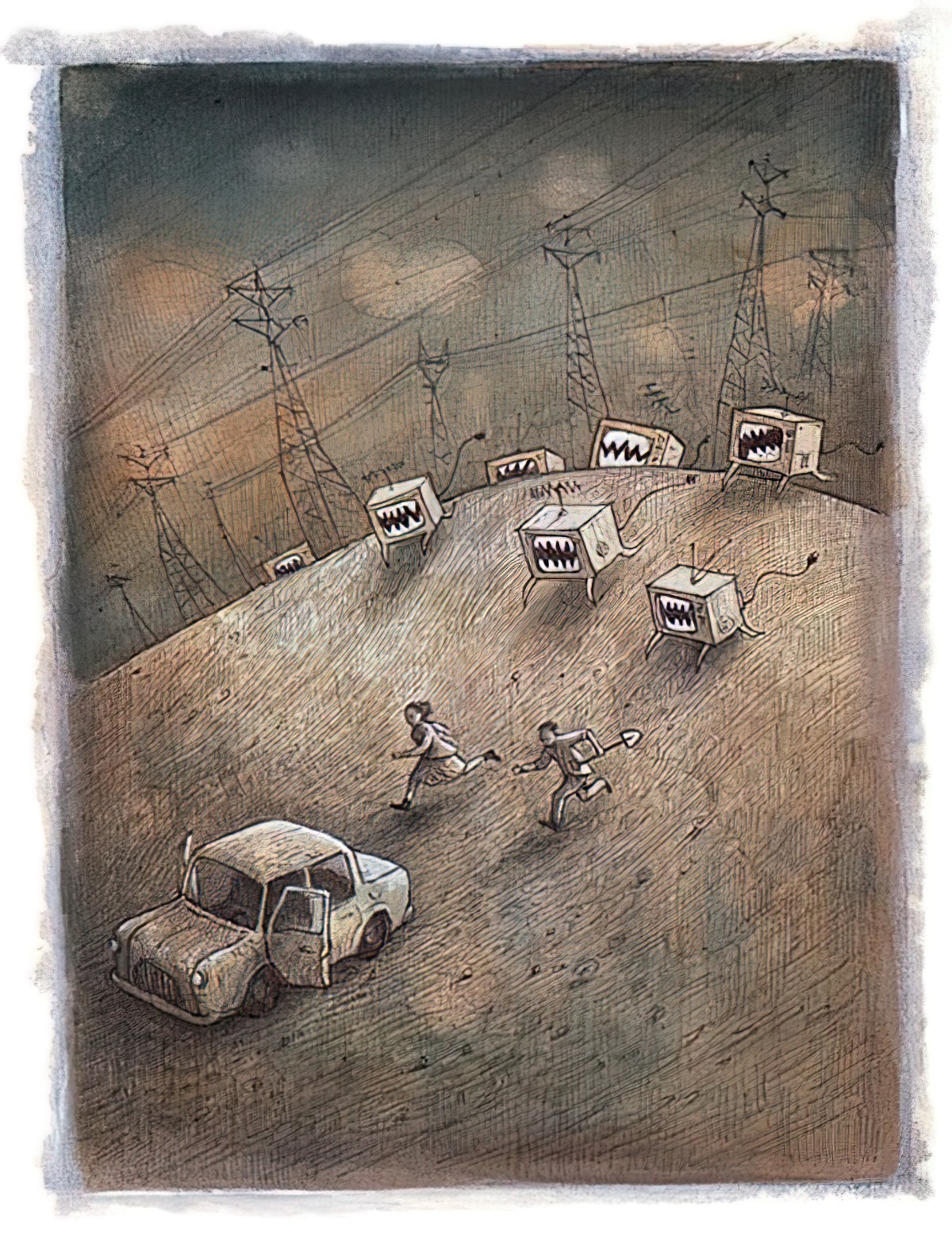

Suburbs have an apocalyptic vibe. Francois Ascher coined the word ‘Metapolis’, literally meaning ‘post-city’. The post-city requires suburbia:

‘Metapolis’ is the new urban form comprising vast networks of cities and towns. The original metropolis now extends beyond its suburbs and its sphere of influences extends to financial activities, social practices and cultural symbolism of people living far beyond its centre. The concept of “commuting” now also includes the abstract notion of tele-commuting as well … Through the use of cellular phone networks and internet superhighways playing the role of ‘spokes’ in a network of sparsely placed ‘hubs’, people can actually partake in the life of a metapolis and influence its functions, without being physically present in it. … it is getting more and more difficult to define the frontiers of this new urban form currently emerging.

The archetypal road-myth: from the highway to the Matrix

The liminal space between cities is the new ‘No-man’s Land’. No one needs to go there when tele-commuting. It’s as if we’ve passed through a tunnel — the spaces between are invisibilized. We rarely give these spaces a second thought. Suburbs are for nights and weekends. Life happens elsewhere, except for the children who spend their lives there, mostly between home and school.

TM: Maybe people are trying to escape the suburbs psychologically.

KB: Yeah, it’s like they’re so bland they can’t be mythic.

TM: Cheever made them mythic. It’s a liminal place, the hybrid city-country.

KB: There’s some French word that I can’t think of at the moment, where city bleeds into countryside, that edge of town. It’s a kind of nowhere land, with odd tensions from either side pulling. Nothing as eerie as walking around a suburb at 4 a.m. on a summer-night morning with nobody around and just a little bit of wind in the trees and leaves. And falling in love or out of love with some girl, and you’re 17. Those moments stay with you, in the sodium [silvery-white] light.

You Can’t Lie in Fiction: An Interview with Kevin Barry

However, Shaun Tan is drawing our attention back to the invisibilized parts of the suburbs, the in-between spaces. He does this overtly in The Lost Thing. Bring that same sensibility to this collection. It will serve you well.

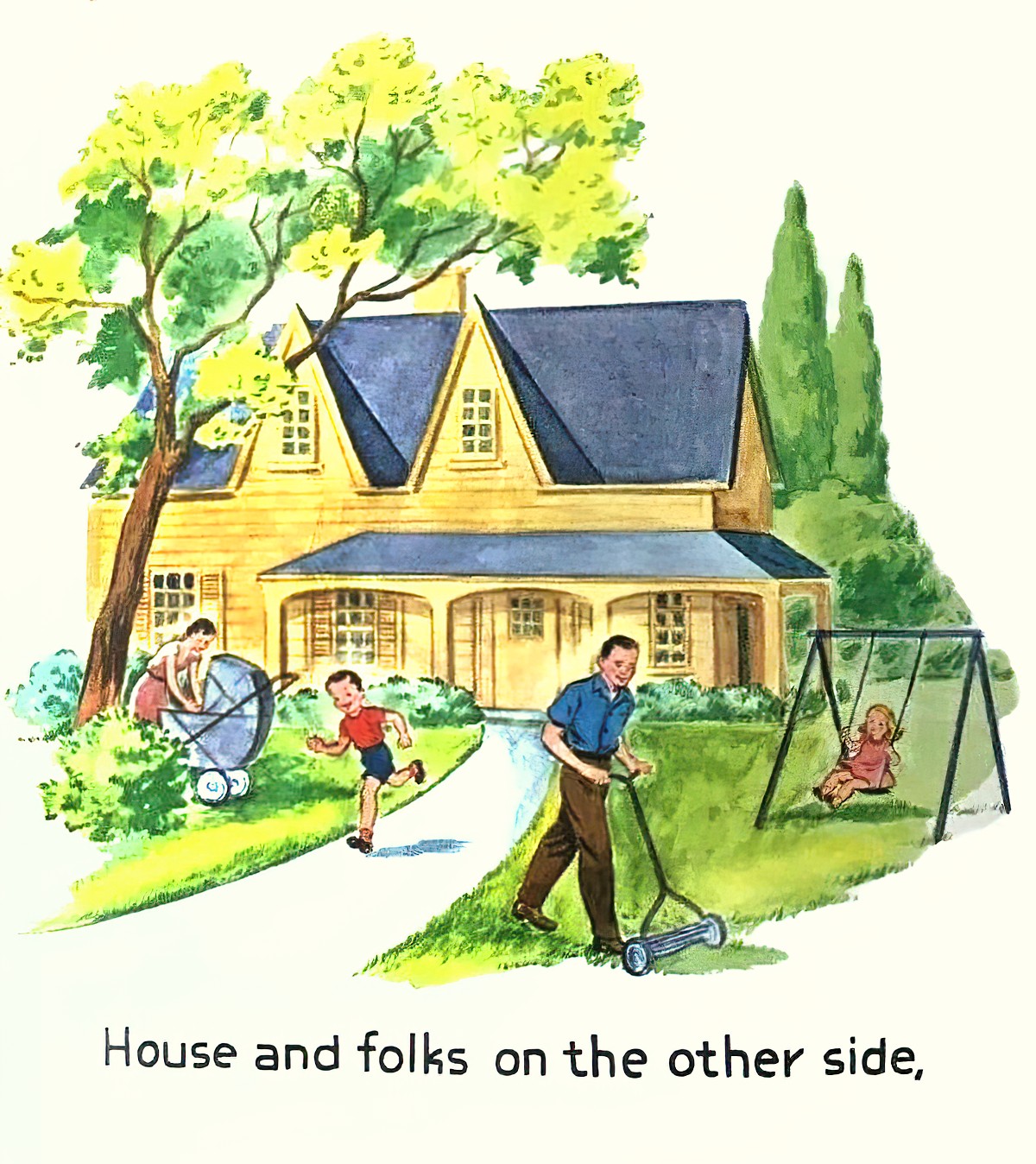

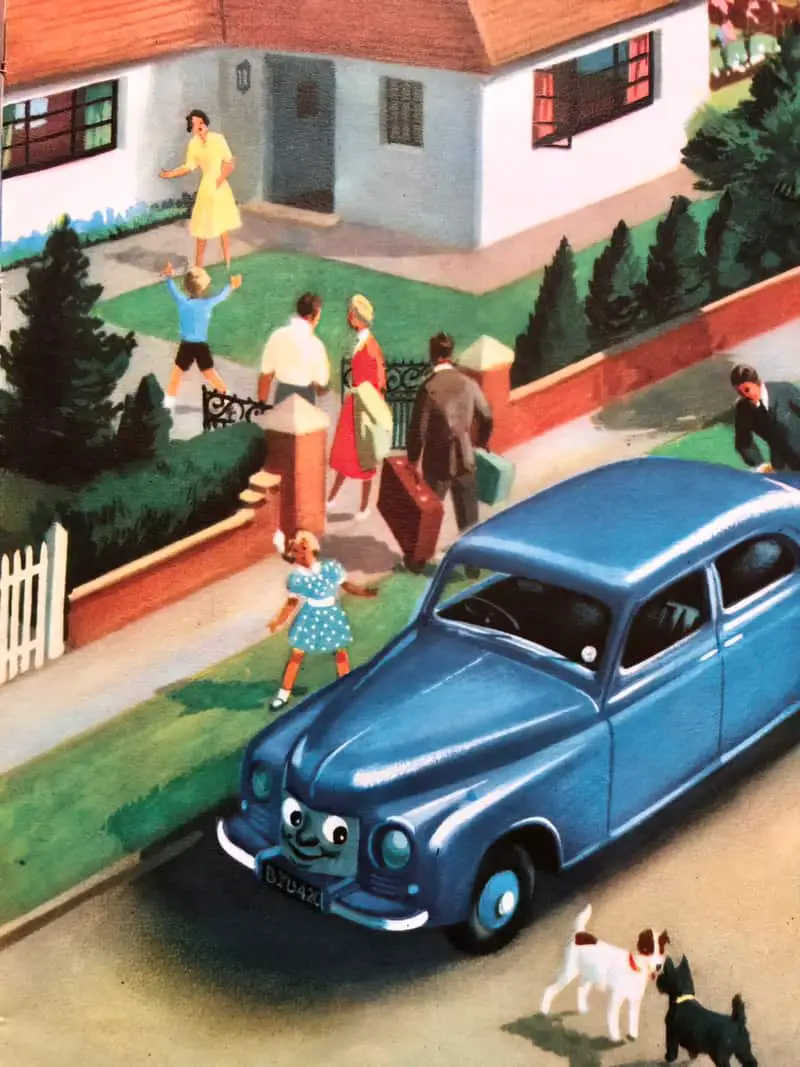

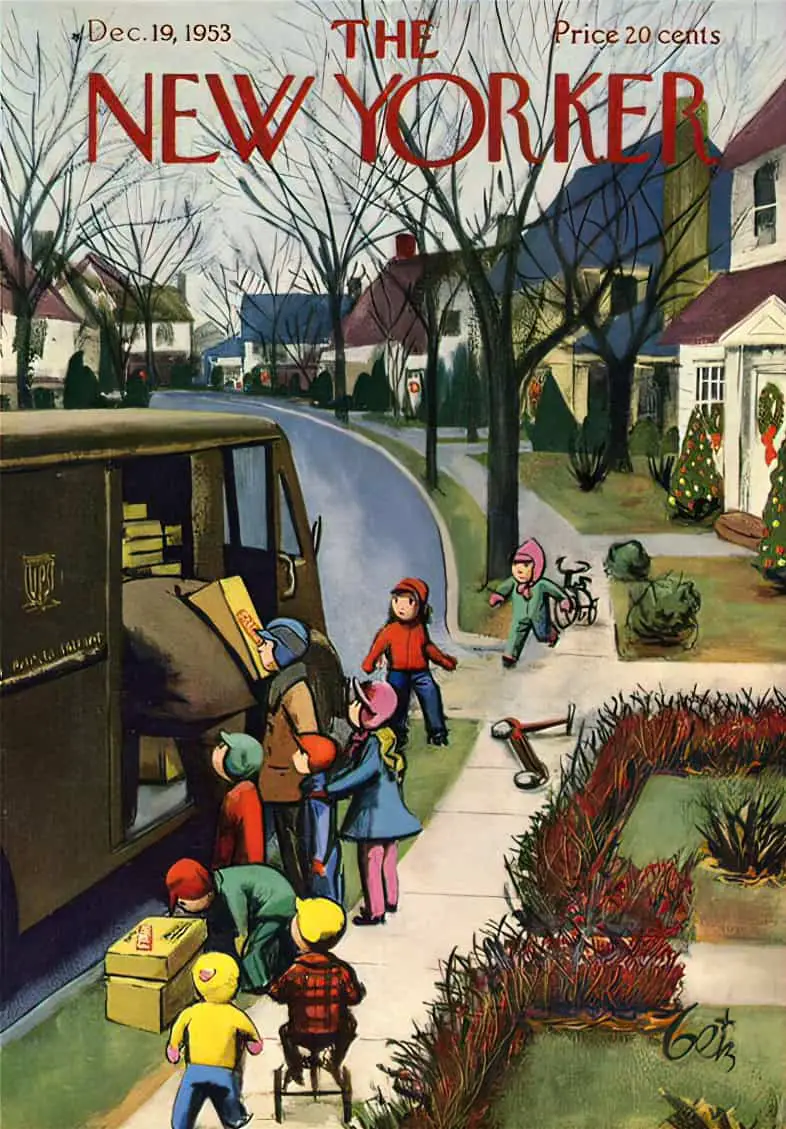

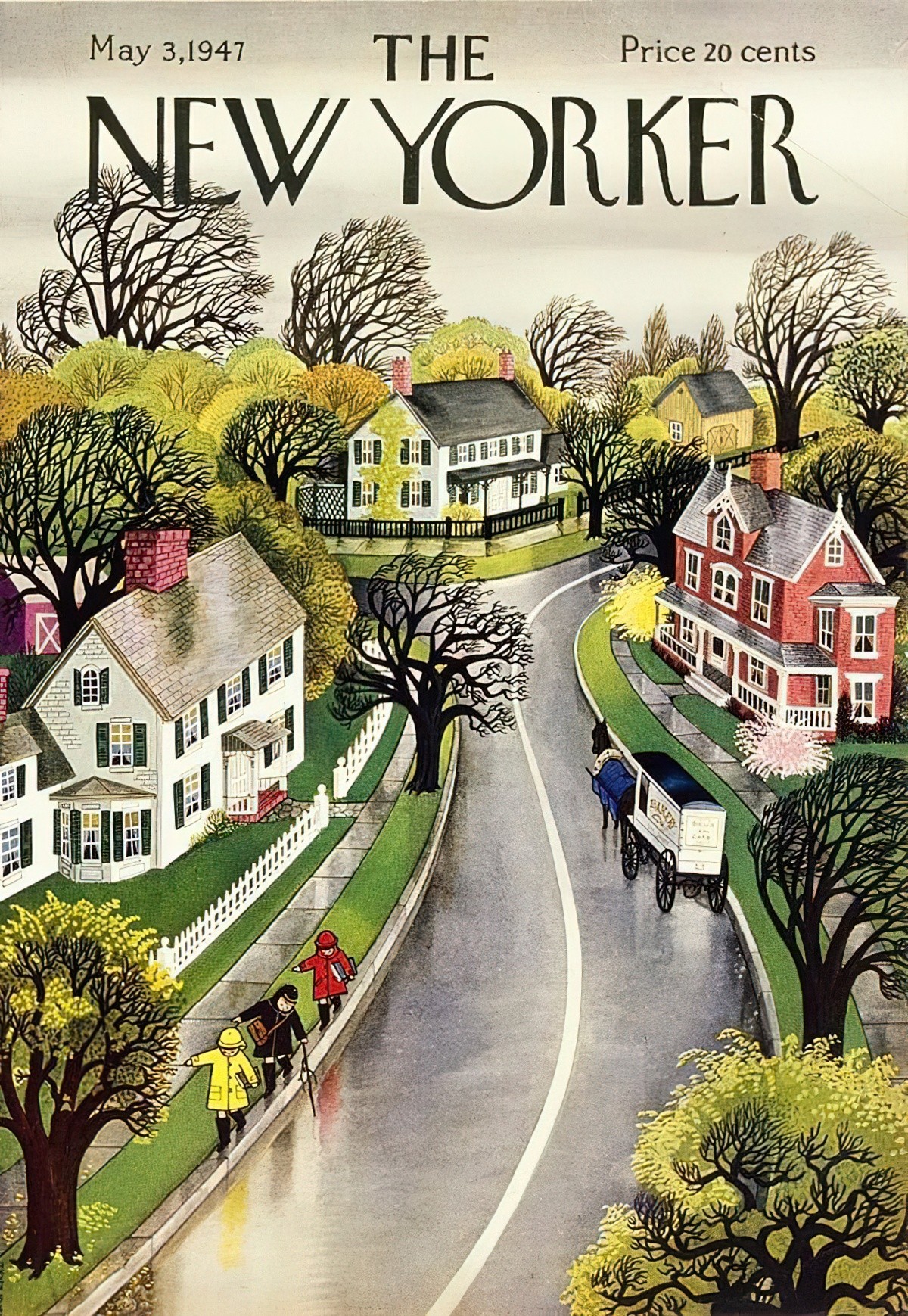

UTOPIAN SUBURBIA OF CHILDREN’S STORIES

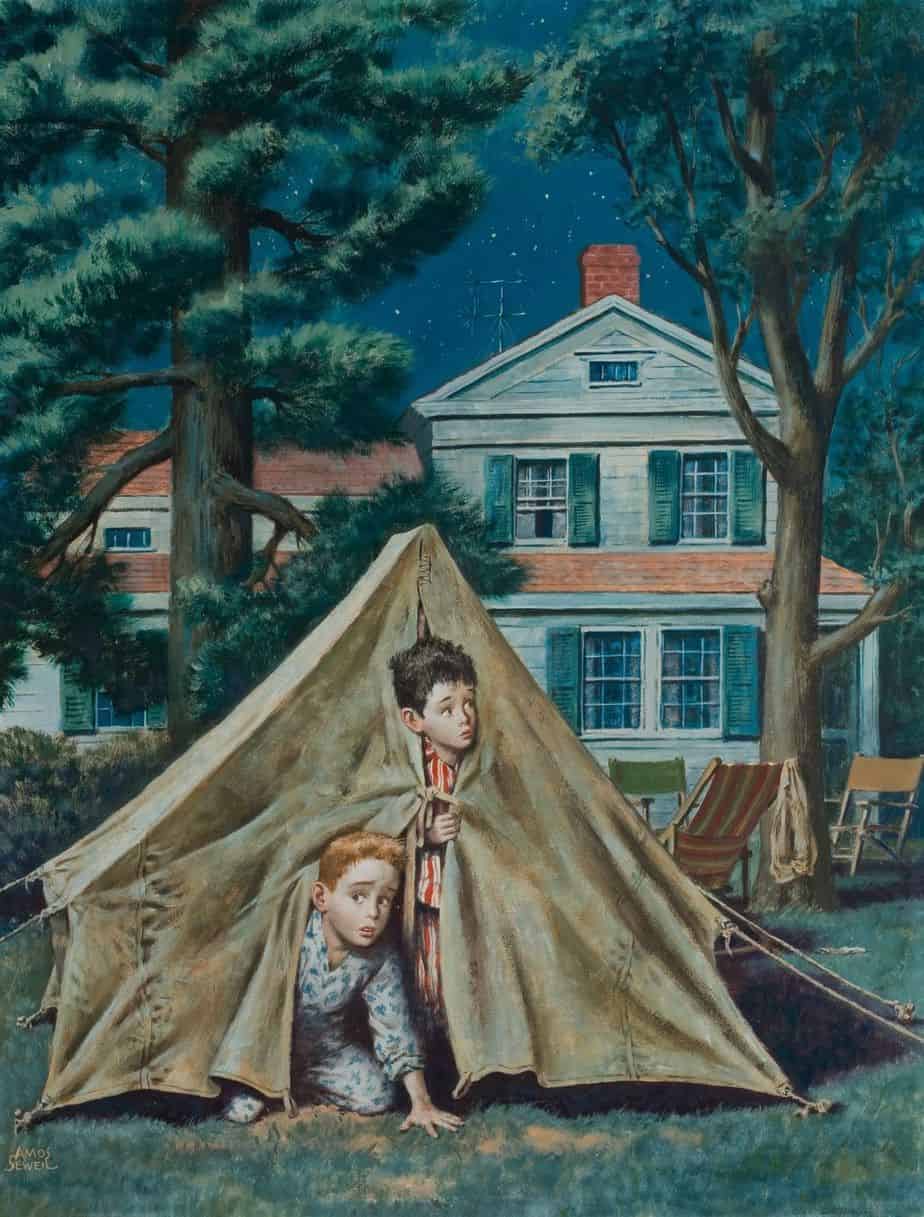

Stories for children frequently idealise the suburbs, though images like “Backyard Campers” by Amos Sewell (for nostalgic adults) depict ‘safe horror’ experiences. The suburbs exist on the edge of civilisation. What are these boys looking at?

SUBURBIA AS SAFE HORROR SPACE FOR PROTECTED CHILDREN

THE ANTI-UTOPIA

In stories for adults, the suburbs are almost always an anti-utopia. Suburbs are a ‘snail under the leaf setting‘, and juxtapose against death.

“The Haunted Boy” by Carson McCullers features a suburban Transylvania. As is the case for Count Dracula’s castle, there’s a ‘lunatic asylum’ nearby, looming over horrors happening inside a house.

Like Carson McCullers, Shirley Jackson is another 20th century author who created the horror of suburbia in fiction. No coincidence how woman (and femme) writers utilised the suburbs as a main fictional setting. Women were expected to spend days in the home. The twentieth century took women from wider communities and deposited them one at a time, each in a separate house. For many, this was a dehumanising and lonely existence.

Again and again, [Tan’s] stories introduce a lonely character in an alienating landscape and then, often by concentrating on some previously overlooked detail, transmute the feeling of isolation into something more like an artist’s sensibility: a more purposeful and yet more playful state infused with an intensely observant appreciation of the secret beauty of life.

Shaun Tan’s Wild Imagination, NYT Magazine

[Shirley Jackson] embodies the midcentury housewife, an idealized and expected role, with plotlines and characters moving beyond societal expectations into a sinister and magical territory: Themes like murder, witchcraft and alienation appear in a discomfortingly combined setting with casserole laden kitchen scenes, dinner parties, and child rearing. There is a place for everything, and everything is in its outwardly maladjusted place.

“Homespun” Horror”: Shirley Jackson’s Domestic Doubling

Below, Claire Messud describes an American suburb in a way that brings even a prosperous suburb to life in the most ominous fashion:

Skandar offered to walk me home. It was only about six blocks, across the slope of the most prosperous stretch of Cambridge, past the dark, still gardens with their looming snow-tipped trees, past cavernous houses in which a single upstairs window shone yolkily out, illuminating a small swath of icy lawn; or past others, shrouded entirely by the night, like sleeping ogres.

Claire Messud

Shaun Tan illustrates with pictures the kind of eerie desolation that is much explored by others in literature. I particularly like Peter Cameron’s description of an American suburb:

It was eerily quiet on my grandmother’s street. She lives in the kind of neighbourhood where the kids are too rich and privileged to do something as simple as play outdoors. They were all at their violin or judo lessons or had been packed off to equestrian or theater camps. The only animate things were the sprinklers, the clapping spigoty kind, spewing shimmering jets of water low over the perfectly green lawns. The sidewalks were old and made of separate plates of concrete, which were cracked by tree roots and the constant shifting of the earth. They were warm and dusty. I thought about the sidewalks in the city, about how mostly gross they were, how you would never want to lie down and rest your cheek on them. But the sidewalks on my grandmother’s street were different, they were like the ruins of ancient Rome, purified and ennobled by time, baked clean by the sun.

Peter Cameron from Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You

To take a random, more contemporary example, Unhinged is a 2020 film. After a confrontation with an unstable man at an intersection, a woman becomes the target of his rage. This version of suburbia utilises the mythic symbolism around crossroads. Suburbs are full of intersections; it’s how they’ve been designed.

When designers try to maximize the number of cul-de-sacs in an area, they create a dendritic—or treelike—system of roads that feeds all their traffic into a few main branches. The system makes just about every destination farther away because it eliminates the most direct routes between them. Connectivity counts: More intersections mean more walking, and more disconnected cul-de-sacs mean more driving. People who live in neighborhoods with latticeworklike streets actually drive 26 percent fewer miles than people in the cul-de-sac forest.

We are pushed and pulled according to the systems in which we find ourselves, and certain geometries ensure that none of us are as free as we might think.

Why cul-de-sacs are bad for your health, Slate

Halloween horror stories for adults and teens turn suburbia into a horror space, upending the notion that our neighbours are trustworthy. When communities disintegrate, we get the feeling our neighbour could be a psychopath for all we know.

MYTHIC TIME IN THE WORK OF SHAUN TAN

Time is not generally linear in these stories. Shaun pulls us into kairos, which is ‘fairytale time‘, compared to chronos, linear time, as we experience it in our daily lives.

For starters, the table of contents is a page of stamps. The stamps are not arranged in any way that will help you locate the story within the book. (Just as well it doesn’t matter which order the stories are read in!) Time is also played with on the back end papers. (A library card suggests your copy is due back on 31 Feb 2056. It’s confronting to realise I’m statistically likely to die around then.)

Within the stories themselves characters will regularly be baffled about how more time has passed than expected. A boy can’t understand how the grass has died beneath a front-lawn creature which had only been there for a few hours. Grandpa tells a story of his disastrous honeymoon. The spare tyre has ‘somehow rusted’.

The style of narration plays into this fairytale dreamspace, with some details remembered as clear as yesterday, while other details have faded away, forgotten forever.

STORIES IN TALES FROM OUTER SUBURBIA

THE WATER BUFFALO

Had to look this up: Australia has two types of buffalo: the river type from western Asia, with curled horns, and the swamp type from eastern Asia, with swept-back horns. I’ve never seen one. The closest I’ve come to buffalo is buying buffalo meat from the eco butcher. (It’s gamey.)

Needless to say, you don’t find buffalo in the Australian suburbs (though you do quite frequently see wallabies and sometimes kangaroos). Tan’s huge creature is alarmingly out of place, though the girl is hardly perturbed by it.

As in many children’s picture books, this buffalo could be real within the world of the story, or it could be a figment of the girl’s imagination.

This is a short allegorical story: People like to have direction. Even if we’re pointing in a random direction, better to have somewhere than nowhere. When life turns good again, we’re likely to assume it’s because we were given good instructions, even if the instructions came from an unreliable source (such as a non-speaking buffalo). A cognitive bias.

I think he went away some time after that.

“The Water Buffalo”

A classic Shaun Tan ending. If Shaun Tan’s stories were songs we’d say they end on a classic fade out. More than that, Tan’s stories are based on recollection, and memory is fickle. Narrators remember the set pieces of some distant childhood, but forget details such as what happened after the resonant event.

ERIC

BROKEN TOYS

Narration breaks the fourth wall; the writer is talking to ‘you’. This is a story by your childhood best friend. Obviously, you don’t remember this story so the narrator is reminding you of it. Has a childhood friend ever told you about an event you were there for, but you don’t remember it at all?

This situation is parodied in Season One, Episode Two of This Country. As the conversation progresses, it becomes clear Kurtan was basically obsessed with a guy his cousin, Kerry, can’t remember:

Kurtan: You don’t remember Robert Robinson?

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: He was in our class in Year 6 for, like, two terms and he just vanished. No-one ever heard of him again. He had… Instead of a rucksack, yeah, he had a suitcase on wheels. And you started his nickname, which was Terminal Three. You started that. That was brilliant. You don’t remember that?

Kerry: Robert Robinson.

Kurtan: You don’t remember? Year 6 camping trip, he brought in an old army camp bed and it had blood on it.

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: We used to bog-wash him so much, the bleach in the toilet actually turned his hair white.

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: Oh, my God! He had about three unruly deaf brothers, yeah?

And he used to get picked up after school in a dirty old Land Rover full of flailing arms.

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: You don’t remember that?

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: He used to write everything out in that calculator font cos he thought it was really cool.

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: We made him eat a fucking bark sandwich, for fuck’s sake.

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: You don’t remember that?

Kerry: No.

Kurtan: Nothing?

Kerry: Nothing.

Back to “Broken Toys”. Random things happen. The story never connects anything for us. We must make connections ourselves:

- A guy in an old-timey underwater suit wandering around the neighbourhood, and who speaks Japanese. (助けて — Help me!)

- Toys which seem drawn to the yard of an old Japanese woman, and which always end up broken.

- The old woman knows the guy, but we never find out how.

- After reuniting with the man in the suit, she seems much happier.

- The narrator and you feel almost sorry for her when she breaks down with emotion.

Broken toys as metaphor for broken heart? Man in heavy suit metaphor for the experience of immigrant dislocation? Is this too easy? Too broad?

In typically Tan style, the story ends on a fade out: ‘We never found out who the diver was, or what happened to him.’

Wait, what is the Japanese connection to broken toys? It took me a while to come to this, but “Broken Toys” is a story about wabi-sabi. Shaun Tan has created a still life painting of a broken toy plane, which means the artist wants us to gaze upon the brokenness. Brokenness as art.

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi (侘寂) is a world view centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of appreciating beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete” in nature. It is prevalent throughout all forms of Japanese art.

Wabi-sabi, Wikipedia

Importantly, the toy plane is a war plane. When reading a Shaun Tan illustration, pay particular attention to the shapes. Those red dots (“solid roundels”) on the wing indicate a Japanese plane, of course. (Also seen on the Japanese flag.)

Japan famously adorned its aircraft with the iconic red disc known as a hinomaru or “circle of the sun.”

Flying Colours – A Short but Vivid History of Warplane Insignia

The circle shape (though not the colour) repeats on the double page spread, though this time the “solid roundel” is the circle of the suit, obscuring the man’s face.

The outtake image is a toy horse, which has been broken and put back together. Another Japanese aesthetic is kintsugi. The word generally applies to smashed lacquerware and ceramics which has been glued back together with the gold seams showing, creating something new and even better than before. Notice, too, the tiny insignia decorating the horse.

It’s too small to make out (at least with my eyes), but could it be the Australian RAAF roundel? I feel like Shaun Tan is making me work for this, because other patterns on the kintsugi-ed horse look like fried eggs (ostensibly barnacles — the toy horse belonged to the barnacled dude).

However I fill in the gaps of this short story, I circle back to death, WW2 and Australia’s relationship with Japan. Kintsugi is such a useful metaphor. It applies to so many stories in which horrible things happen, things are never the same, just a new kind of different.

A mystery I can’t work out: The double page spread contains two kanji which look like an artist’s signature.

甬刀

Is this someone’s fictional name, invented by Shaun Tan? Search engines are no help.

The word would appear to be pronounced ‘youtou‘ (going with the kan-on reading) or ‘yuutou‘ (going with the go-on reading). Youtou would be homophonous with ‘magical sword’. The second character is common and definitely means ‘sword’. (You may even be familiar with the loanword, borrowed into English: ‘katana’, referring to a Japanese single-edged sword.)

However you’re meant to pronounce it, that first character has an interesting standalone meaning:

A ‘road with walls on both sides’, huh? Well, that must be symbolically significant. I know enough Japanese to avoid taking English translations of kanji literally, because it all requires cultural context before the fullness of meaning can be understood. Still, I’m fascinated in how the English translation matches what Shaun Tan has created here: A literal road, and callbacks to a war in which both sides did wrong. Shaun Tan only shows us one side of that road, with a ‘wall’ of suburban houses.

Anyway. After trying to look this up, I only have further questions. The more the search engine tells me, the less I understand. Some things are like that…

UNDERTOW

This story has a realism layer and an allegorical layer, recreating the hopelessness we all feel when whales beach themselves. We don’t know why they do it, or how to help them. The sea creature in this story is even more confronting, as it beaches itself on a boy’s front lawn.

This happens to a backdrop of marital discord. The boy’s parents argue. When we are kids we never know the full story around why parents argue. The reason for his parents’ argument is as baffling as the lawn creature. The feeling of helplessness and overwhelm is the same for each thread of the story, as is the feeling that a massive thing just happened to your household. So why does everyone around treat this as a workaday event? Your parents shouted at each other. Hasn’t the world just shifted forever?

In this two-track way, “Undertow” is an excellent example of a story with a realism thread mirrored by a fantasy/speculative thread. As far as plot goes, the two threads have nothing in common. But when it comes to emotional response, the threads are identical for the boy. One is allegory for the other.

When the parents find their son lying in the shape of dead grass, left behind after people came to take its body away, they seem to be affected by the sublime, just as the boy is. Unexpectedly, they carry their son silently to bed without scolding him.

Both images are high angle. One is a bright image, under harsh Australian sunlight, the other is of the same view but at night. This time the boy lies where the creature was earlier, perhaps trying to imagine what was going through its mind, perhaps spiriting himself away.

Are the two plots really so disparate, though? Let’s go back to the title. Undertow. Look up a dictionary and the polysemy of words becomes apparent. (Polysemy: The coexistence of many possible meanings for a word or phrase.)

Undertow:

- a current of water below the surface and moving in a different direction from any surface current. “I was swept away by the undertow.”

- an implicit quality, emotion, or influence underlying the superficial aspects of something and leaving a particular impression. “there’s a dark undertow of loss that links the novel with earlier works”

The concrete* meaning concerns bodies of water. The metaphorical meaning concerns human psychology.

*Linguists talk about concreteness vs. metaphoricity. ‘Concrete’ doesn’t mean ‘you can touch it’. Something with a ‘high concreteness rating’ can be experienced by any of the senses, not just touch. It’s not binary, either. Words get a rating, and sit along a spectrum between concrete and metaphorical/abstract.

GRANDPA’S STORY

[T]here are … stories like “Grandpa’s Story” that takes the hero’s quest to find the magic token in order to marry the princess, and subverts that sexism by presenting the feminist story of two equal fiancées on a dangerous, life-threatening scavenger-hunt as part of their marriage ceremony. This is a story that can thrill young children, but also intellectually stimulate older readers.

The Book Wars

Shaun Tan is making use of the plot points straight out of fairy tale, as described by Vladimir Propp. How many can you find?

The style of the illustrations in this story remind me very much of the creepy trees of Arthur Rackham.

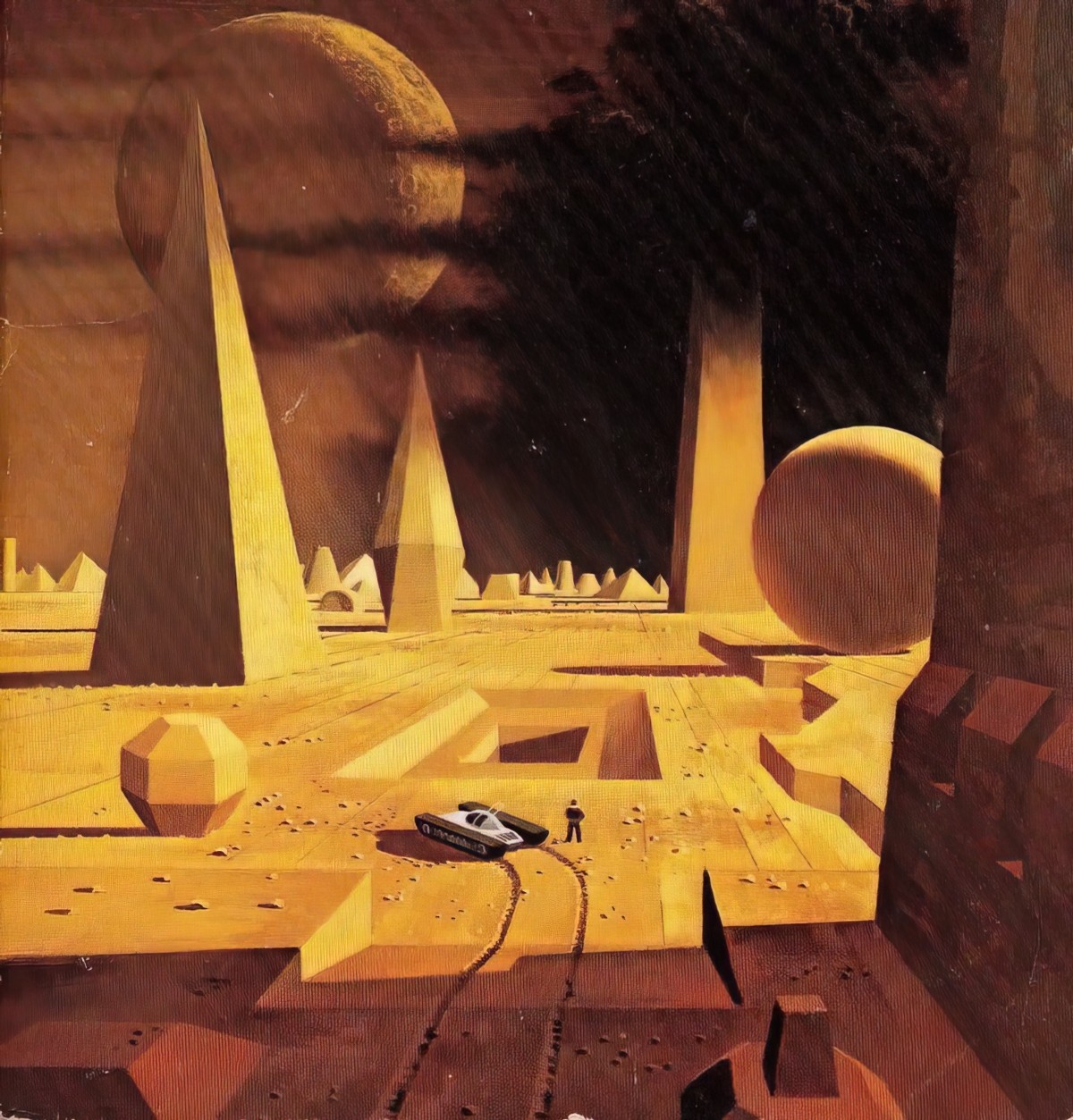

In a number of Shaun Tan’s stories, including in this one, cityscapes appear as unwelcoming, sharp-edged concrete blocks.

[G]igantic, imposing buildings made of concrete.

Some people refer to this building style as “Brutalist architecture,” but Brutalism is a big, broad label that’s used inconsistently in architecture, and architects tend to disagree on a precise definition of the word. Furthermore, the word “brutalism” has intense connotations, even though it’s not actually related to “brutality.” The word comes from the French “béton brut,” which means raw concrete.

The Smell of Concrete After Rain from 99% Invisible

(Melbourne, Australia, is one of the Brutalist-architecture capitals of the world.)

Concrete presented the most efficient way to house huge numbers of people, and government programs all over the world loved it—particularly Soviet Russia, but also later in Europe and North America.

Philosophically, concrete was seen as humble, capable, and honest—exposed in all its rough glory, not hiding behind any paint or layers. Concrete structures were erected all over the world as housing projects, courthouses, schools, churches, hospitals—and city halls.

The Smell of Concrete After Rain from 99% Invisible

NO OTHER COUNTRY

“No Other Country” is a re-invention of the portal-quest fantasy (a subgenre more typically for children, such as Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), though this story features far less adventure and a lot more peace.

The Book Wars

Every story with a portal is compared to the Narnia Chronicles. I’m reminded of Tom’s Midnight Garden. Like “Eric” and “Broken Toys”, this is a story of Australian immigration. The images are reminiscent of medieval paintings, but with the addition of contemporary Australiana, notably the Hill’s Hoist clothes lines.

Hills Hoist: The Iconic Rotary Clothesline That Shaped Australian Suburbia from 99% Invisible

STICK FIGURES

These stick figures are literally made of sticks (more like branches) from trees. They’ve come alive and walk around the neighbourhood with clods of tussock for heads. Gangs of ‘older boys’ attack them.

The illustrations are framed like Polaroids — a bus stop, a carpark, non-descript except for a stick figure in the frame, or just out of it, casting long shadows in the evening light.

Polaroids are an example of objects which have come and gone from our lives throughout history, mostly because something new has been designed to fulfil their functions more efficiently. See more examples of so-called ‘extinct’ objects which were either imagined and never in use, or which existed but are now unused in Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects (Reaktion Books, 2021). (Interview with several of the authors at New Books Network.)

The story ends with questions rather than providing any answers:

It’s as if they take all our questions and offer them straight back: Who are you? Why are you here? What do you want?

Stick Figures

That paragraph could be a part of almost any story by Shaun Tan.

THE NAMELESS HOLIDAY

A plot description of this tale would have you think it’s a Christmas story, but Christmas is not mentioned. Traditions around leaving cookies and milk out for Santa and his reindeer form a direct link to this story, but instead of leaving food, children leave their favourite things for one enormous reindeer.

We only see its shadow, reminiscent of England’s Uffington White Horse, except this reindeer appears on the hill leading down from an ominous playground. The only sign of life: One black bird.

This illustration is one of the few etchings of Tales From Outer Suburbia.

THE AMNESIA MACHINE

Designed to look like a newspaper article, “The Amnesia Machine” features a black and white “photo” of townspeople looking up at a feat of human engineering in the sky.

After reading the story, I realise how many of the people in the crowd are not looking at the amazing giant object at all. Like the narrator, whose reason for writing is presented in a slightly different font, they soon lose their sense of wonder and instead turn to the small, near and relatable: The flavours of their ice-creams.

For me this story is an allegory about how we take massive breakthroughs in science for granted, impressed one day, taking it for granted the next.

This newspaper article is surrounded by others, which are mostly unreadable because the sentences and paragraphs end where the page ends. Still, there’s enough to provide basic themes, which only prove more relevant to society as time goes on. Australia is not quite living in a post-truth world, but when this book was published in 2008, truth and journalism was an increasing concern. “Meltdown Not So Bad After All”, we can deduce from another headline.

We don’t just fail to appreciate the good things in life. We underestimate the bad. So much is going on, we have no idea where to place our attention.

ALERT BUT NOT ALARMED

In another genre of story, a ballistic missile in everyone’s yard would lead to societal collapse. But in the hands of Shaun Tan, we get a gentle ending.

Turn the page for a magnificent vista of repurposed violence, with beautiful colours reminiscent of Australian birds (also in the picture).

See also: Artest palettes of Bright Sunny Days.

MAKE YOUR OWN PET

There’s a word for digital art which emulates the look and feel of hand-made, real-world materials: Skeumorphism. The torch function on your phone, with its satisfying ‘click’ sound on the button is an example of ‘haptics’, but it also emulates how old-style switches had to work. That’s skeuomorphism.

Likewise, we see skeumorphism in graphic design. In “Make Your Own Pet”, Shaun Tan has designed the page to look like someone has cut scraps out of a magazine, The headline is supposedly constructed from individual words gleaned from other headlines. There’s a ransom-note vibe going on whenever that happens (though I wonder if that association remains for a younger generation, who grew up in the age of computers).

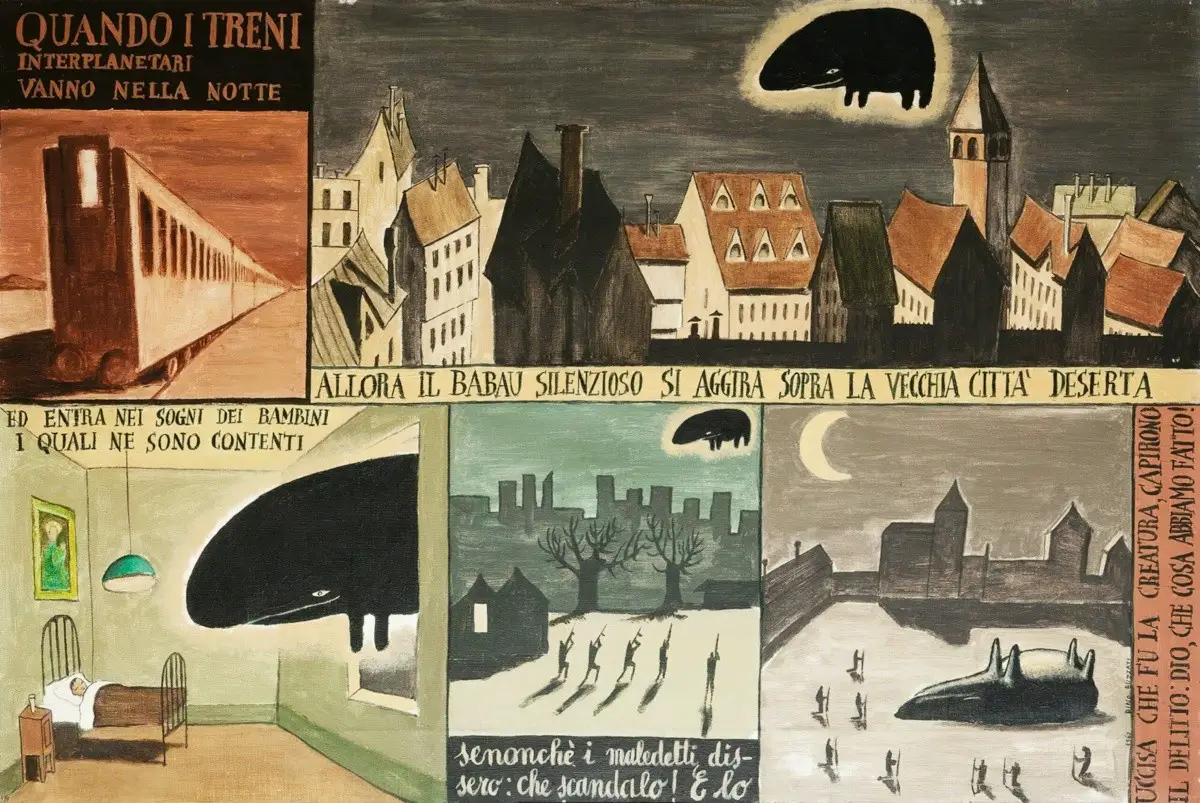

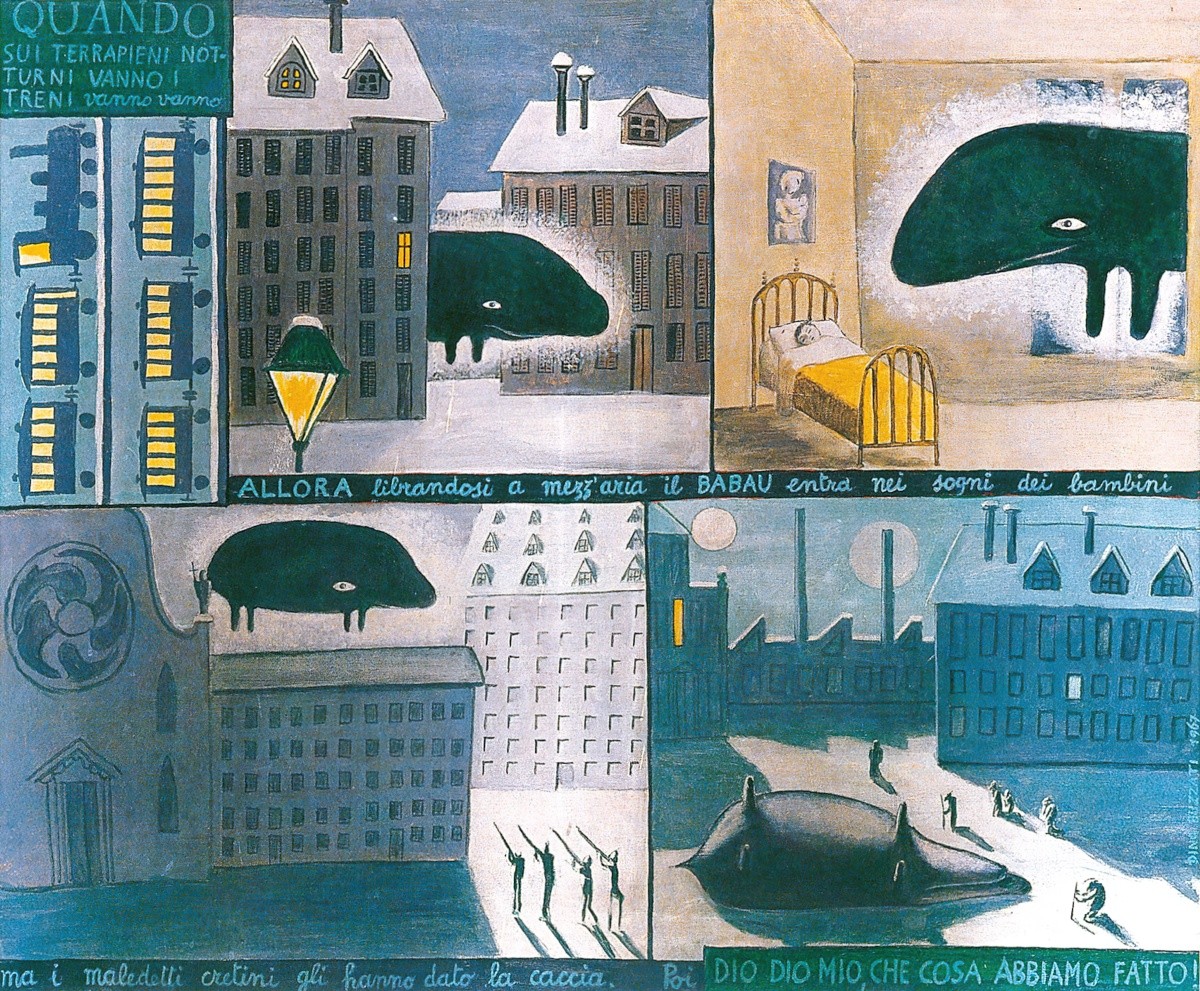

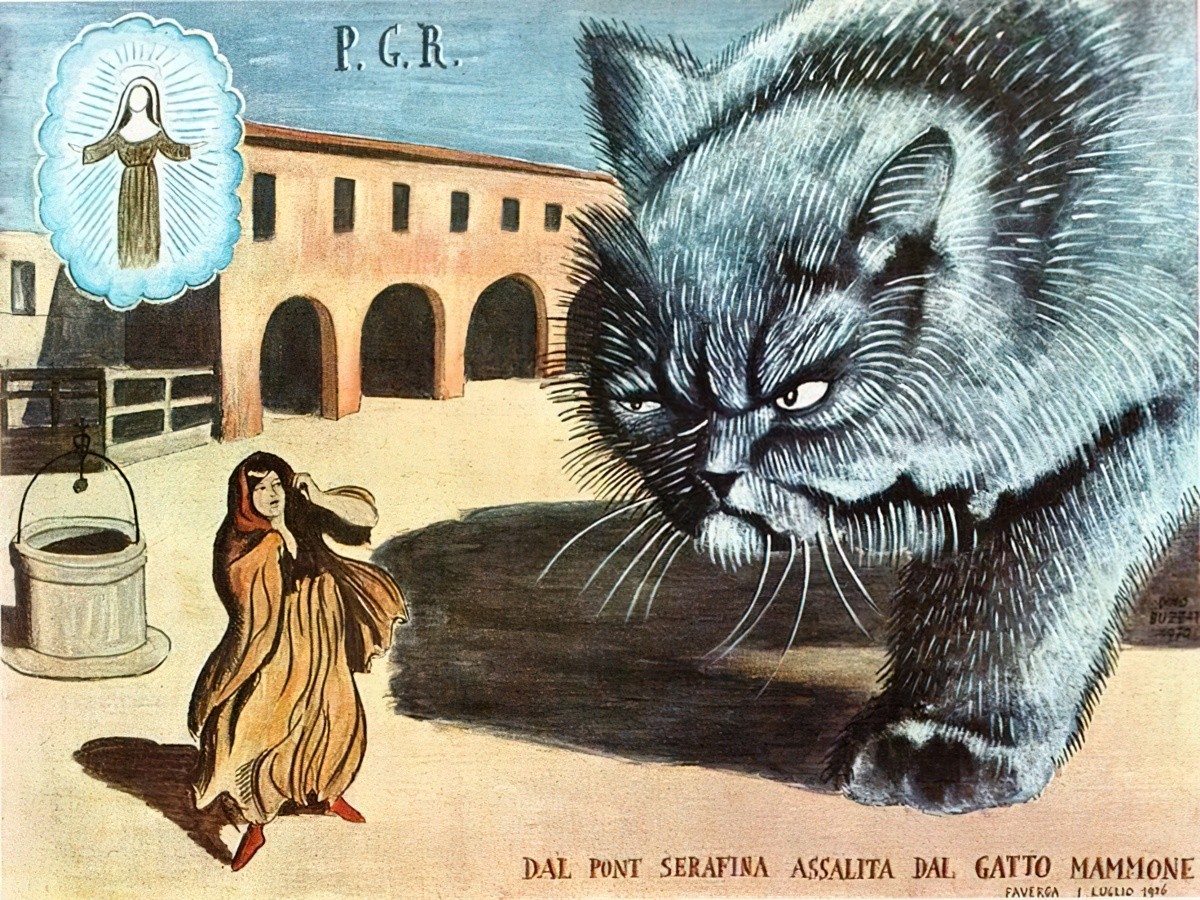

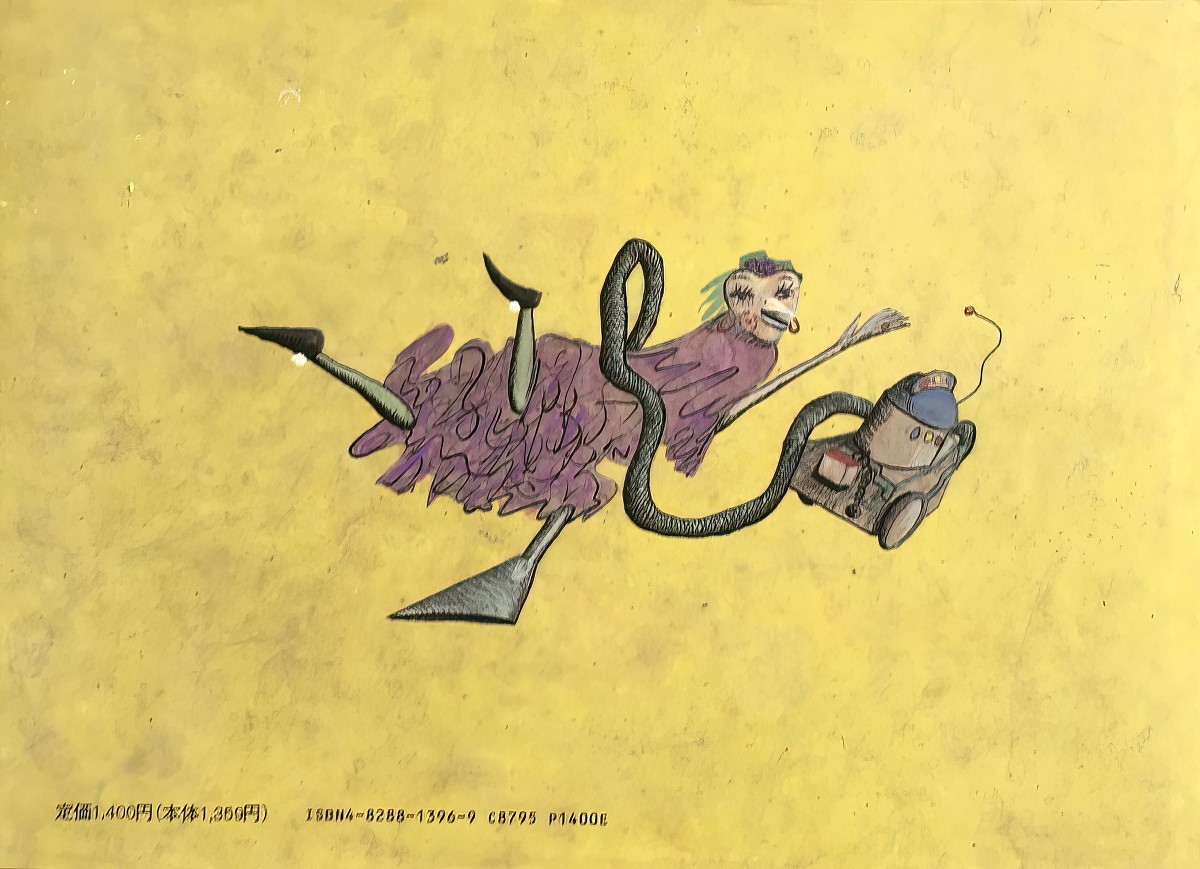

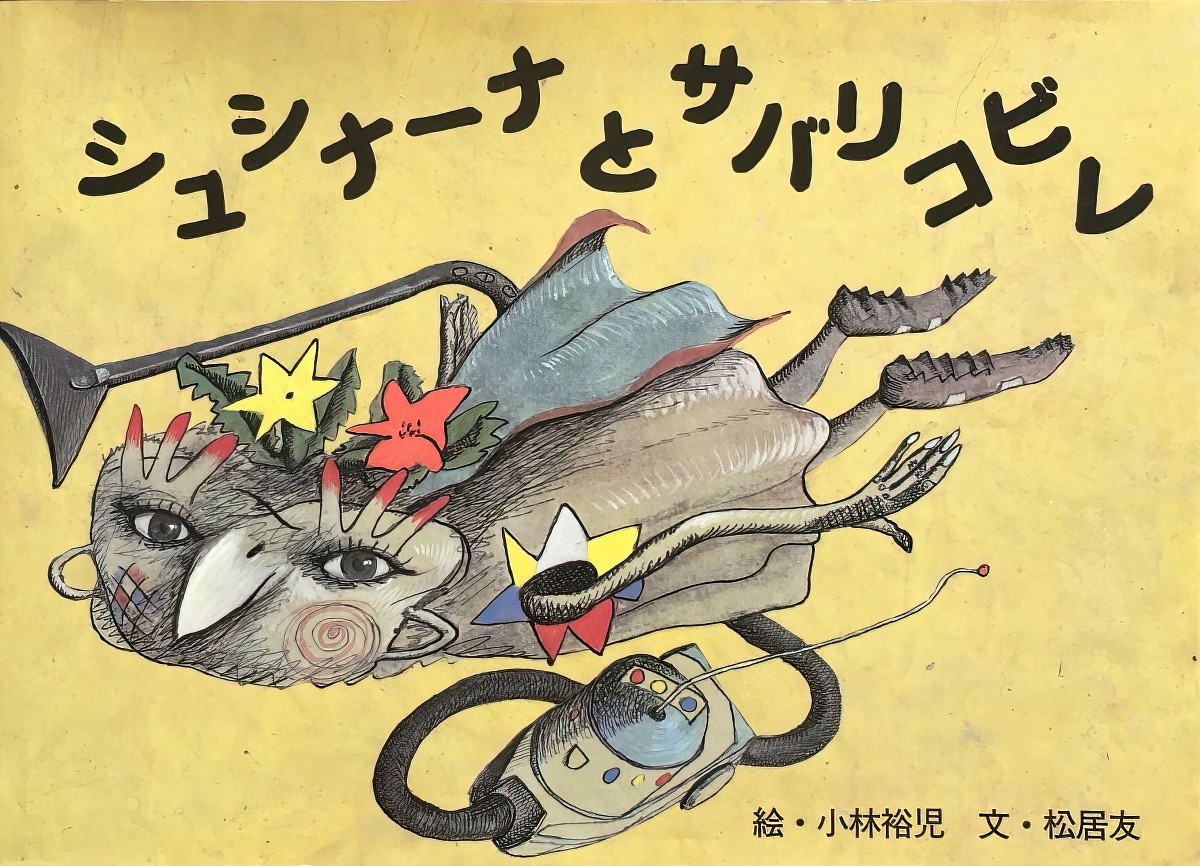

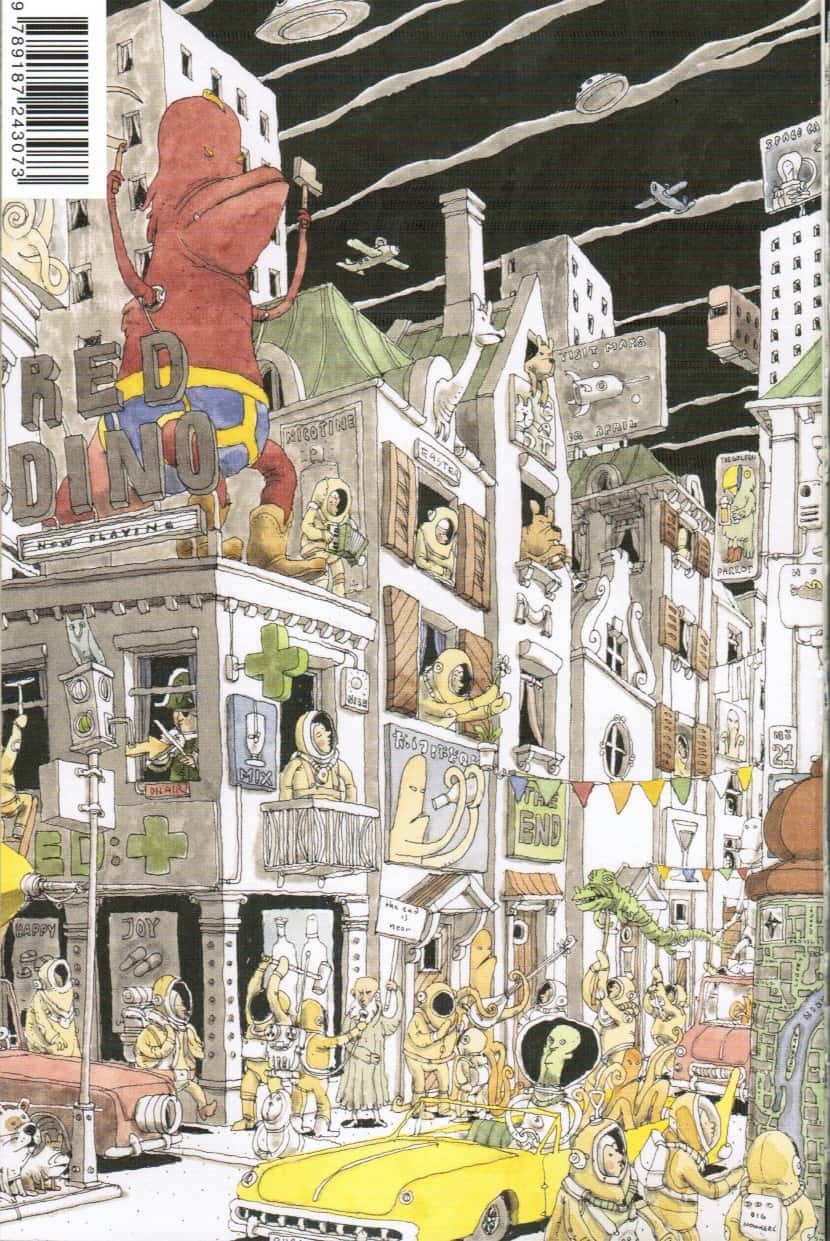

Take a look at “Make Your Own Pet” Next look at the image below. Dino Buzzati was an Italian Symbolist Surrealist painter, and Shaun Tan’s work reminds me of his. Like Tan, Buzzati had multiple ways of telling story. He was a novelist, short story writer, painter and poet, as well as a journalist.

Here’s a similar layout utilising a cool palette.

If you enjoy Shaun Tan’s “Make Your Own Pet”, I recommend an odd but beautiful speculative picture book called Aviary Wonders, Inc.

WAKE

This is a revenge tale, and one of the angriest and confronting of Shaun Tan’s stories that I’ve read. Fortunately the killing of the dog happens off the page at the start. Dogs hold a wake at his house.

OUR EXPEDITION

Two young brothers walk along suburban roads past malls and streets identical except for their names, scaling multilevel parking garages to get their bearings and making notes in an exercise book. At sunset, they reach the limit of their map and, apparently, of the world. In the story’s final image, they dangle their sneakered feet over the sheared-off edge of a road into a great pink-tinged void with puffy white clouds and a single black bird. Down below, water cascades from projecting drainage pipes into the unknown.

“When we were growing up, a lot of the area around Perth was still under development,” Tan’s older brother, Paul, told me. “Now it’s sprawl, but we were on the fringes then, and there was a lot of bush. We would walk a long way, all the way to the beach.” Paul, who grew up to be a geologist, collected rocks. Shaun collected shells, among other things, and drew them.

Shaun Tan’s Wild Imagination, New York Times Magazine

As the boys continue to explore the never-ending loop of suburbs, each with recognisable riffs on big brand names, the camera zooms up and out.

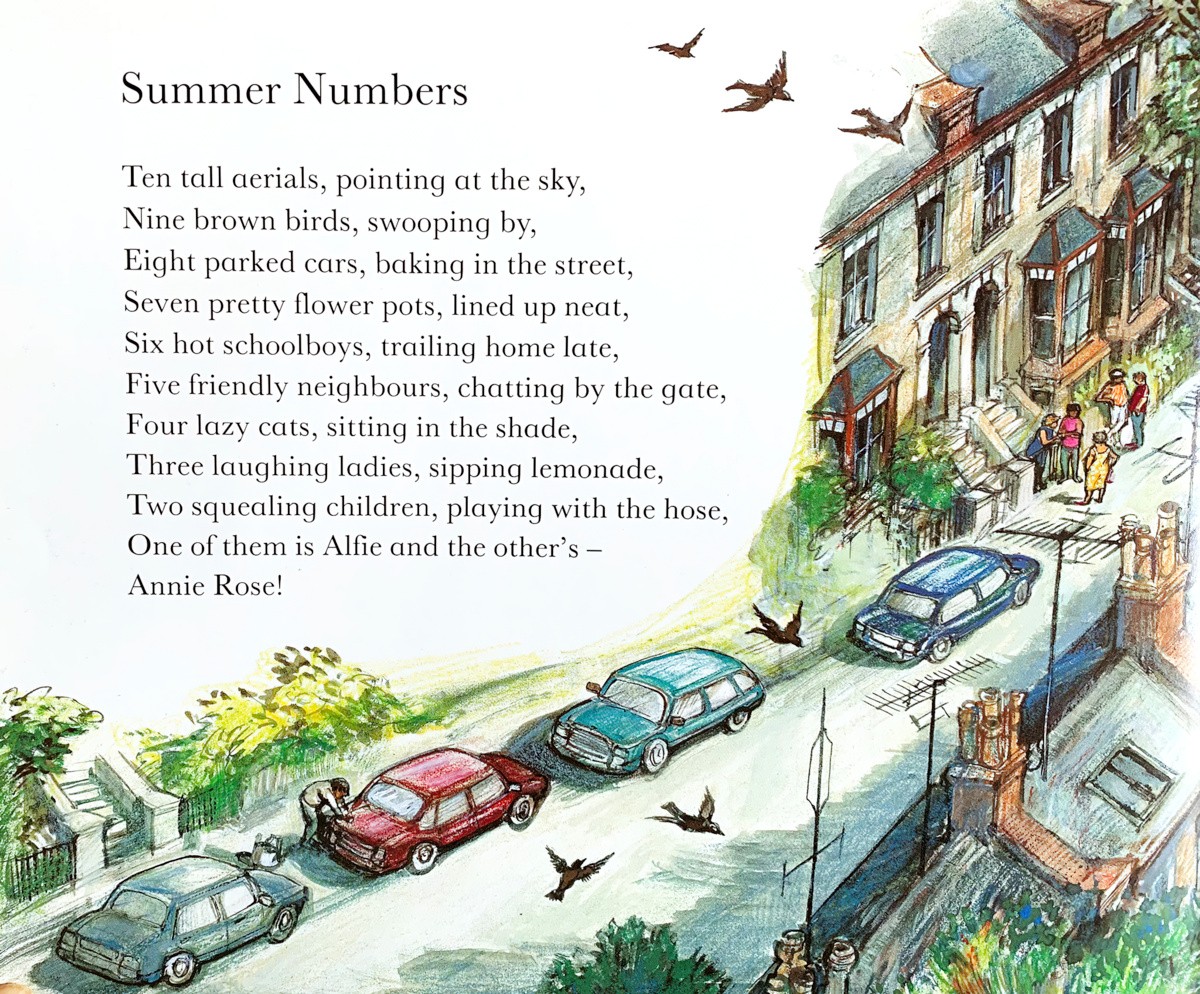

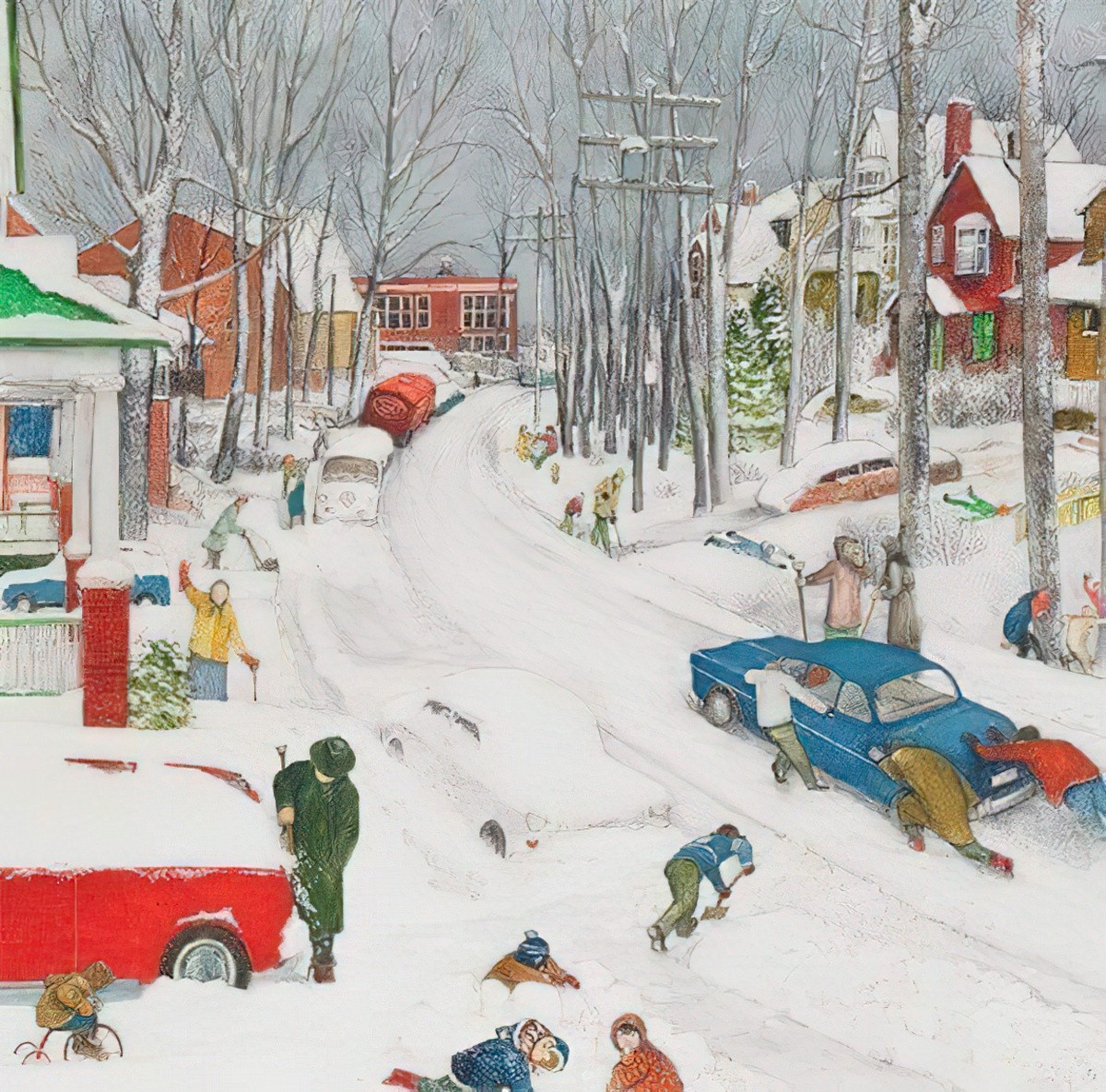

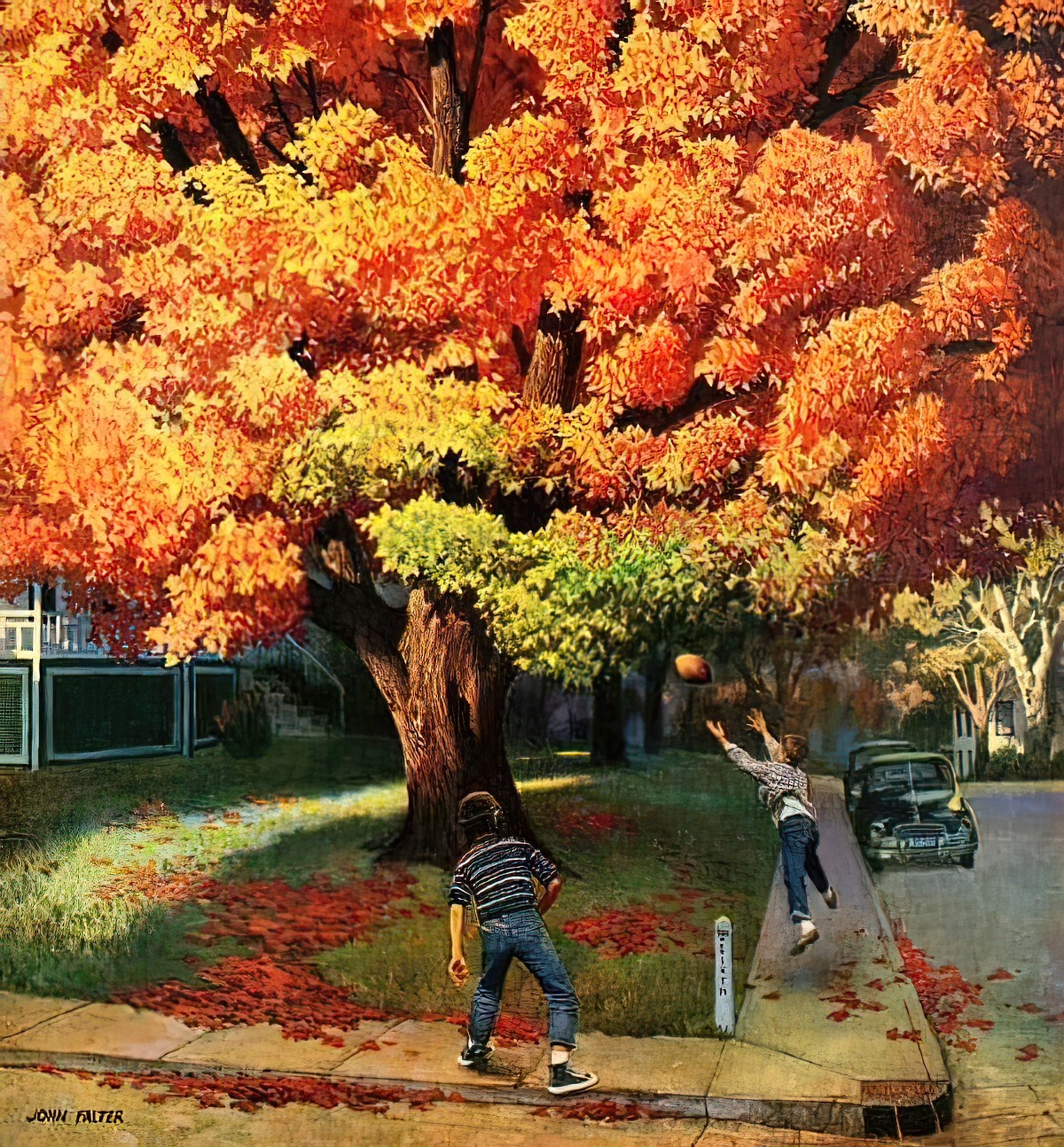

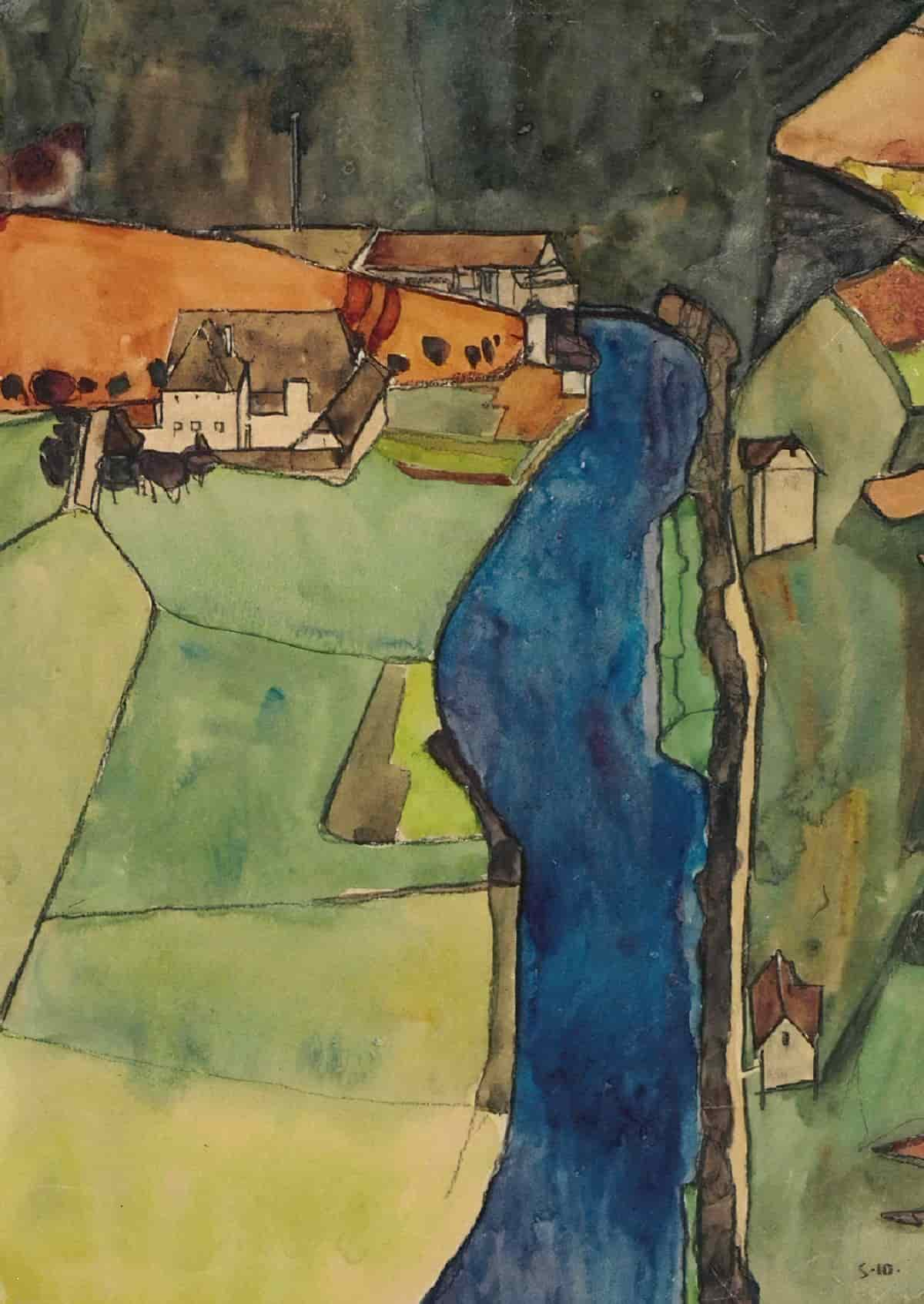

More top-down views of suburbia:

NIGHT OF THE TURTLE RESCUE

One paragraph of story fades from white on black into grey. On the recto, a utility vehicle with turtles rescued from death on a labyrinth of stacked freeways. The dimming of the text mirrors the way headlights work when driving at night.

The ironic gap between text and image: The turtles know what the driver of the vehicle does not: They are being chased along the freeway by a pack of wolves.

Or was the narrator really describing wolves when the title led us to believe he was describing turtles?

OTHER SHAUN TAN-ESQUE IMAGES TO FEED THE IMAGINATION

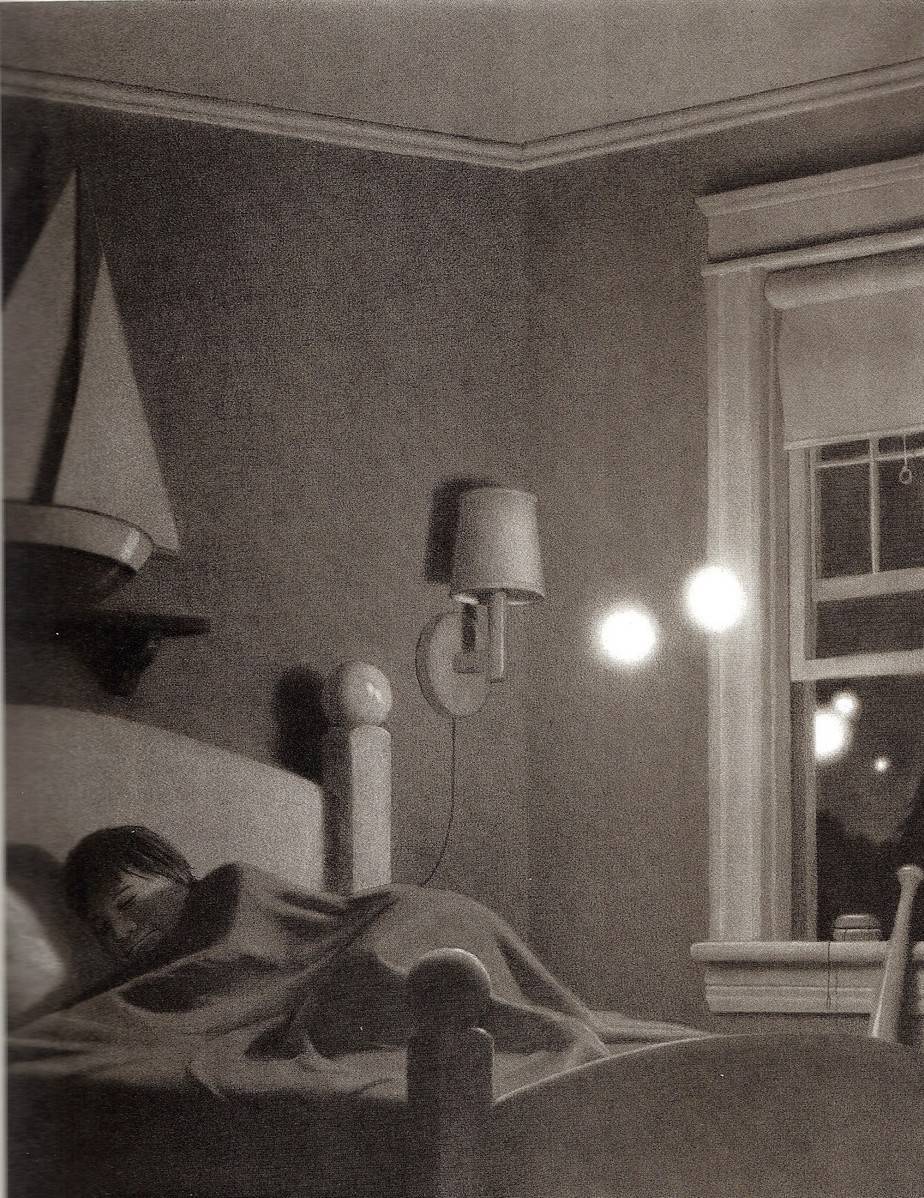

- Photographs by Gregory Crewdson are highly staged and a lot of work goes into the post-processing as well, to create eerie stills of the suburbs, often at night at on dusk.

- Another photographer of the (American) suburbs: William Eggleston. Eggleston has a much brighter palette, reminiscent of the 1960s. He has an interesting way of framing still life. Strong shadows are a distinctive feature.

- Simon Stålenhag is a Swedish artist. Like Shaun Tan, he creates his images from scratch (digitally, rather than from photography). Also like Shaun Tan, his suburbs contain speculative elements. Check out his books, e.g. The Electric State.

FURTHER READING

…for those of us both writing and illustrating our own books. This conversation between Neil Gaiman and Shaun Tan was published a while ago, and has helped me edit my own work:

I usually refine the text last, partly because pictures are harder to do so it’s easier to edit words – I use text as grout in between the tiles of the pictures. I always overwrite, really awful, long bits of script and then I trim it down to the bare bones and then add a little bit to colour it in. At the end of all of my stories I test for wordless comprehension. So I remove the text and see if it works by itself. And if it does I feel that that’s a successful story. I don’t know if that’s an important principle but it’s helped me structure things.

RELATED TO SUBURBIA

How People Live In The Suburbs, A Vintage Gem, shared by Brain Pickings

Post-boomer generations tend to think of suburbia as conservative, well-manicured and relentlessly boring. But our suburbs can offer the ideal medium between city and country living: proximity to all the cultural, business and career opportunities of cities with more space and more quiet for less money.

The reason why suburbia in Australia never appealed to me is that these spaces are often infrastructure deserts and therefore essentially unliveable without a car. Moving around any other way feels unsafe and wrong – like scuba diving in a busy shipping port. Australians, like North Americans and increasingly Europeans, accept this as a given – a trade off you have to make for gaining more space.

The Dutch show us, however, that suburbs can be more human-friendly and accessible without giving up car ownership completely. This excellent comparison between Dutch and Canadian suburbs by YouTube channel Oh The Urbanity! makes a very appealing case for suburbia.

Issue 244 of Dense Discovery newsletter

A SIMILAR PICTURE BOOK

Chris Van Allsburg’s picture books work in a similar way: Postmodern and Surreal, they appeal to adult and children alike.

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick is a collection of pictures which do not form a sequential narrative in their own right. Each picture tells its own story. This would be a wonderful way to inspire a class of students who are about to embark on a creative writing exercise.

FURTHER READING

[Shaun Tan] says people often make the mistake of calling him a children’s creator.

Author and illustrator Shaun Tan on seeing the world through children’s eyes and the importance of doubt