Duel is a 1971 TV movie, which became a feature film and launched the career of American director Steven Spielberg.

“Duel is basically Jaws on land. I really think it qualified me to direct Jaws.”

Steven Spielberg

Less well-known: The film Duel is based on a short story by Richard Matheson (1926-2013), who also wrote I Am Legend. He also wrote a number of episodes for The Twilight Zone, and many other things, some you’ll have heard of. Matheson himself wrote the teleplay and screenplay for Duel from his own short story. After all, the guy was an experienced screenwriter as well as a fiction writer.

Find the short story in Matheson’s Duel: Terror Stories.

The film was originally made for TV. TV movies have a shorter filming schedule. Duel took no more than 3 months to make. It was shot on location in less than 2 weeks. This is an amazingly tight schedule by any standard. Spielberg’s passion for the project helped spur the team along.

The film was made on a very low budget, especially considering how much it made at the box office. 25-year-old Spielberg never looked back, and over his career garnered the reputation for finishing movies before the deadline. But perhaps his main talent is surrounding himself with wonderful crew.

PARATEXT

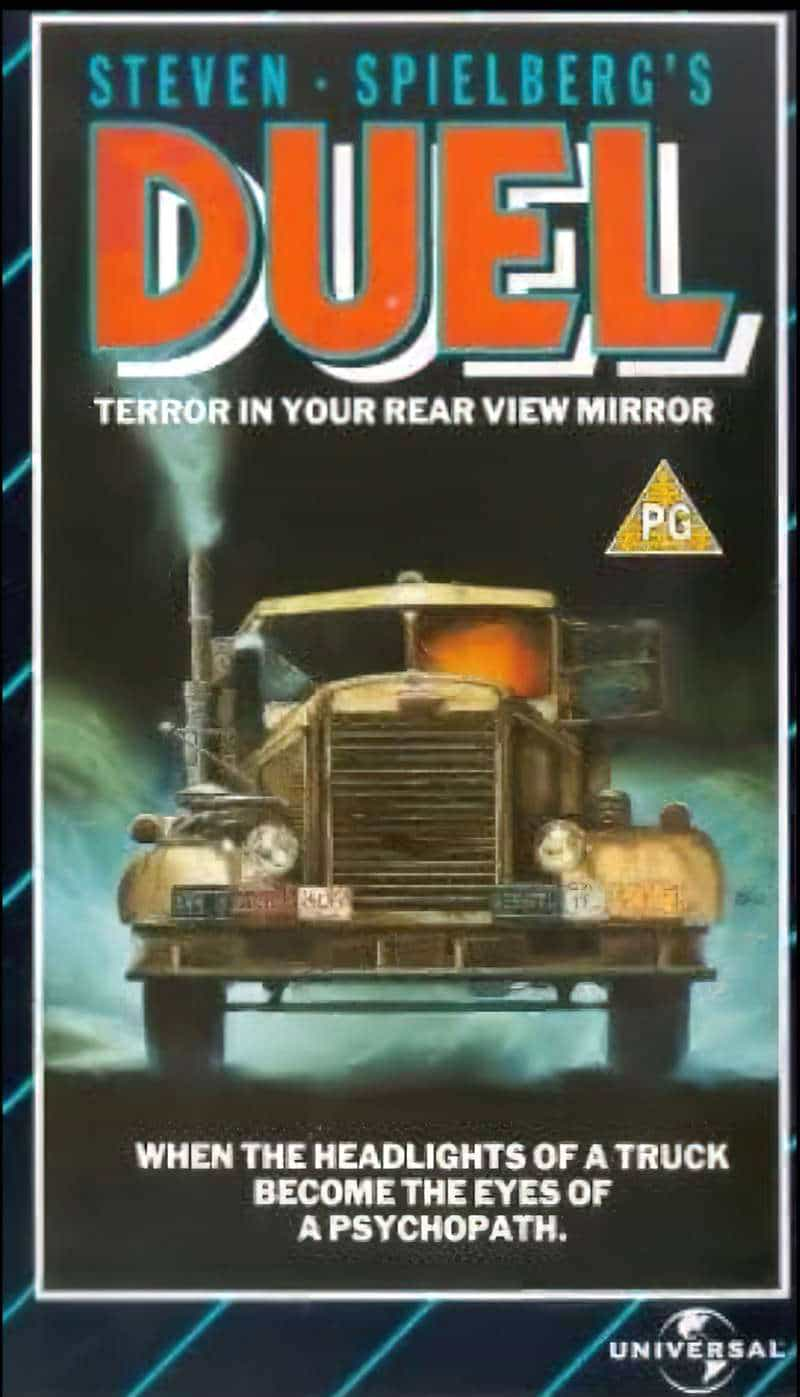

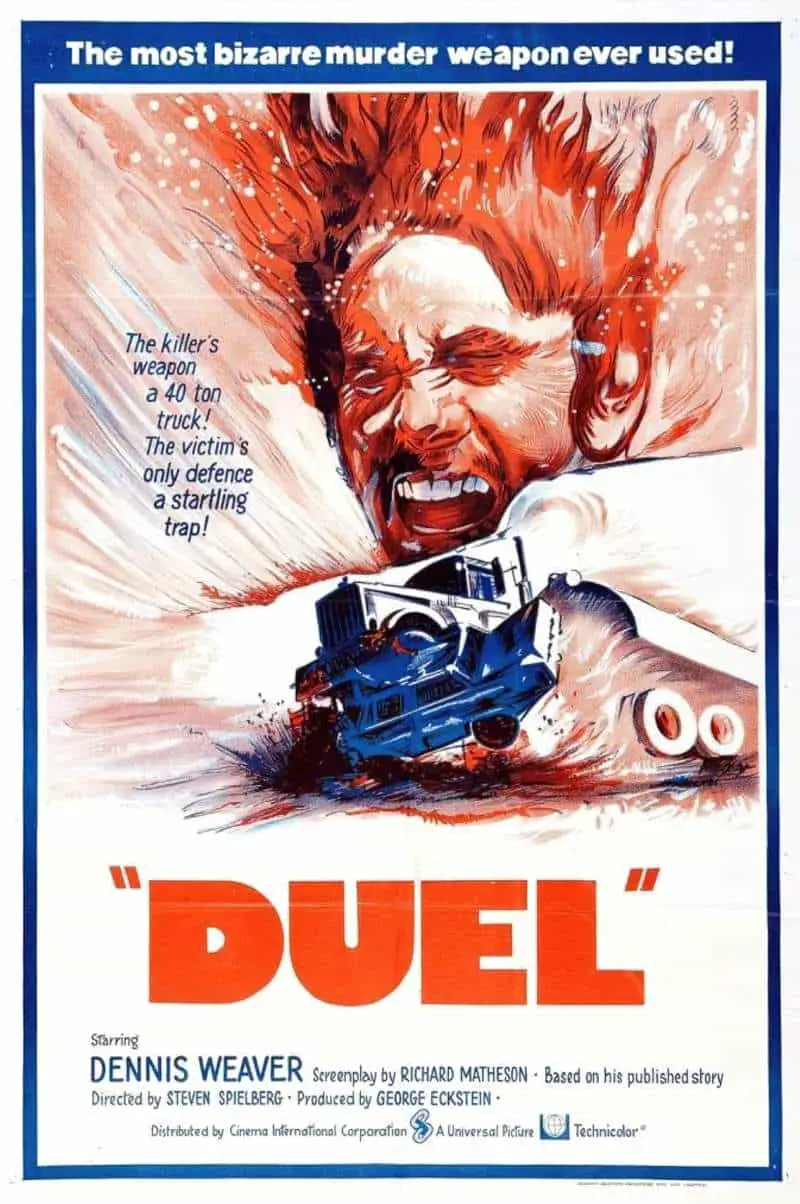

DUEL MOVIE POSTERS

TAG LINES

- When the headlights of a truck become the eyes of a psychopath.

- A duel is about to begin between a man, a truck and an open toad. Where a simple battle of wits is now a matter of life and death.

- The killer’s weapon a 40 ton truck! The victim’s only defence a startling trap!

GENRE

Audiences loved Steven Spielberg (and others like George Lucas) because this new breed of director blended drama with other genres which offered brilliant spectacle.

RESONANCE

The fear of sharing the road with trucks is evergreen, at least until the world switches over completely to self-driving vehicles. (And I have no idea how that switchover will be managed, when some vehicles are driven by AI, some by more fallible humans.)

Australia is very similar to the USA regarding the reliance on road transportation of goods. We don’t have a good train network here, so if you don’t have and drive a car, outside the cities you’re basically isolated. If you drive any of the main roads at night, you’ll meet mostly trucks. Some Australian trucks — the ones which deliver goods to the Northern Territory — are so big they’re known as ‘road trains’.

TRUCKS ON THE ROAD

Trucks are involved in a disproportionate number of road fatalities. About fifty percent involve a truck. If drivers of private vehicles find trucks ominous, there’s a good reason for it.

Sometimes it’s because drivers are impatient to pass them, as they block field of view. Oftentimes it’s because truck drivers at at fault. They may have been driving too long without a proper break, their health disregarded by corporations who employ them.

SETTING OF DUEL

PERIOD

The 1970s

The model of the red Plymouth Valiant, the bowsers at the petrol stations, cement the story in its era. (The main guy’s sunglasses have come back into fashion since.)

DURATION

The film is basically isochronical, meaning it seems to happen in real time. However long it takes you to watch this movie, that’s how long the battle goes on for.

Spielberg had his start in TV, and his TV career was short but very successful. He had an eye for screen direction even in his early 20s.

A 74-minute version of Duel was originally made as a TV movie. Spielberg added 16 more minutes to make it feature film-length. (Matheson wasn’t involved in the expanded part with an extra four scenes, two written by Spielberg, the other two written by producer George Eckstein.) Unfortunately, the only version of Duel available now is the theatrical version. The original teleplay has never been released for purchase. (It has occasionally played on TV in the United Kingdom.)

To coax viewers into feeling as if we are the man driving the car, Spielberg first lulls us into that super relaxed almost meditative state you can find yourself in when you’re driving long distances on an open highway in light traffic. This affects the pacing.

OTHER FILMS KNOWN FOR THEIR SLOW PACING

Films known for their deliberately slow and contemplative pacing include:

- Barry Lyndon (1975) – Directed by Stanley Kubrick, this period drama is known for its slow, deliberate pacing and stunning cinematography.

- Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) – Directed by Chantal Akerman, this film is renowned for its extremely slow and methodical portrayal of a woman’s daily life.

- The Turin Horse (2011) – Directed by Béla Tarr, this Hungarian film is celebrated for its extremely slow and minimalistic style.

- Satantango (1994) – Another film by Béla Tarr, “Satantango” is famous for its long takes and patient storytelling.

- Stalker (1979) – Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, this science fiction film is known for its contemplative and unhurried pace.

- La Soufrière (1977) – Directed by Werner Herzog, this documentary captures the eerie stillness and tension of an impending volcanic eruption.

- The Assassin (2015) – Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, this Taiwanese martial arts film is renowned for its slow and deliberate action sequences.

- Gerry (2002) – Directed by Gus Van Sant, this minimalist film follows two friends as they get lost in the desert and features long, uninterrupted shots.

- Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011) – Directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan, this Turkish film is celebrated for its slow and deliberate storytelling as a group of men search for a buried body.

- A Ghost Story (2017) – Directed by David Lowery, this film explores themes of time and existence and features long, uninterrupted shots and a slow, methodical pace.

- An Elephant Sitting Still (2018) – Directed by Hu Bo, this Chinese film is known for its extended running time and unhurried storytelling.

- Certain Women (2016) – Directed by Kelly Reichardt, this film weaves together the lives of four women in rural Montana with a patient and reflective pace.

- Silent Light (2007) – Directed by Carlos Reygadas, this Mexican film features long, slow takes and a contemplative narrative.

- Cemetery of Splendor (2015) – Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, this Thai film is celebrated for its dreamlike, slow-paced storytelling.

- In the Mood for Love (2000) – Directed by Wong Kar-wai, this Hong Kong romantic drama is known for its lush cinematography and deliberate pacing.

- Stellet Licht (2007) – Another film by Carlos Reygadas, this Mexican drama is marked by its slow and immersive style.

- The Tree of Life (2011) – Directed by Terrence Malick, this film combines a slow and contemplative narrative with stunning visuals.

Although audiences have become accustomed to a faster pace in all media, films with a deliberately slower pace continue to get made, and enjoyed. The meditative pacing of Duel isn’t a 1970s thing. There is an argument to be made that Duel doesn’t benefit from the extra 16-minutes which were added for largely bureaucratic reasons rather than storytelling reasons.

THE INFLUENCE OF JOHN FORD

Of course, ‘slow’ movies are only slow when you’re not picking up on one of the layers. This is how one person can find a film exhilarating, another person would rather watch paint dry. If you find Duel too slow, but are interested in watching it anyhow, it helps to be interested in how film-makers frame their shots.

Spielberg is known for shooting action sequences a lot like John Ford. Both directors like to push information out of the frame, for instance. He composes and recomposes inside a contiguous shot.

John Ford directed 150 films over his career and is remembered for his Westerns and wartime documentary work. He eschewed the Hollywood lifestyle, was often grumpy when interviewed and rarely attended awards ceremonies. His influence on Steven Spielberg is well-known.

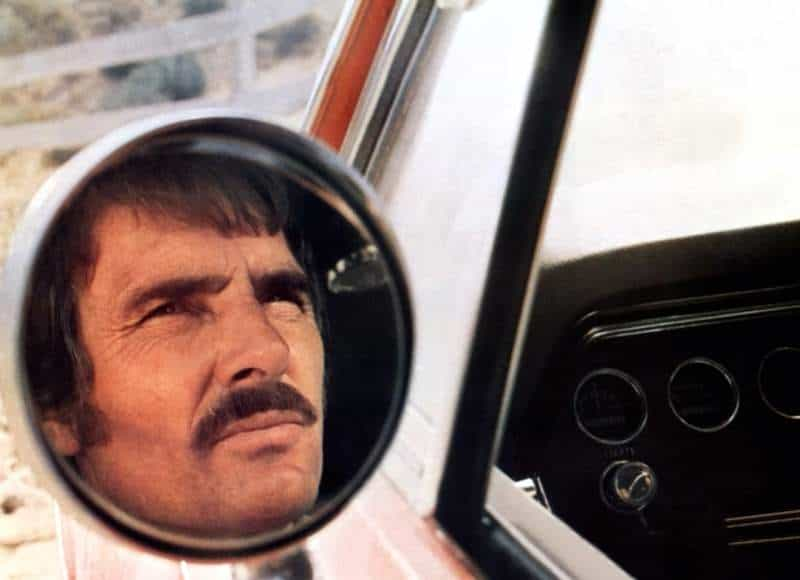

‘Reflections in mirrors’ is a recognisable John Ford influence.

Also keep an eye out for:

- The camera zooms in for a close-up on a character’s face at a dramatic moment

- John Ford’s famous chase sequence in Stagecoach (1939) is now considered textbook cinema. Spielberg inherited the smoothness of the camerawork.

- Conveying story without reliance on dialogue. Steven Spielberg wanted even less dialogue in Duel but the network insisted on having more. Spielberg was as sneaky as he could be and cut more than was originally ‘agreed upon’. International versions of Duel cut out even more. (Dialogue is preferred by viewers who aren’t reading the visuals, but film buffs generally prefer less.)

Listen, smile, agree, and then do whatever the fuck you were gonna do anyway.

Robert Downey Jr.

- Any dialogue scenes are followed immediately with something very nice/interesting to look at, a visual scene of some sort.

- Where there is violence, it’s over very quickly. The suggestion of violence is the real terror.

- Close-ups mean something. Most of the shots are long shots and mid-shots.

- John Ford was known for his fade to blacks and dissolves, not used much in modern cinema. These days it draws too much attention to itself.

- John Ford believed that the ‘quiet little man’ has more guts and courage than the big noisy blowhard. That worldview is shown at the ending of Steven Spielberg’s Duel. Ordinarily, a car has no chance against a murderous truck.

Spielberg took these John Ford tricks to a whole new level, utilising new technologies such as the much lighter cameras of the 1970s. Younger directors go further with this again, and modern movies have much more ‘staccato’ editing, partly because they can. Steven Spielberg has directed Duel in that old, classical style.

John Ford’s films featured a number of insignificant woman characters. Women just weren’t important to him. I feel Duel inherited this unfortunate aspect as well. When the story cuts to the wife at home, this is clearly designed to up the stakes for Mr Mann and his survival. Audiences are supposed to care for him more because he is a Family Man. (Single people are given less value, by society as well as in film.) The wife on the end of the phone has no backstory of her own, which means she comes across as whiny.

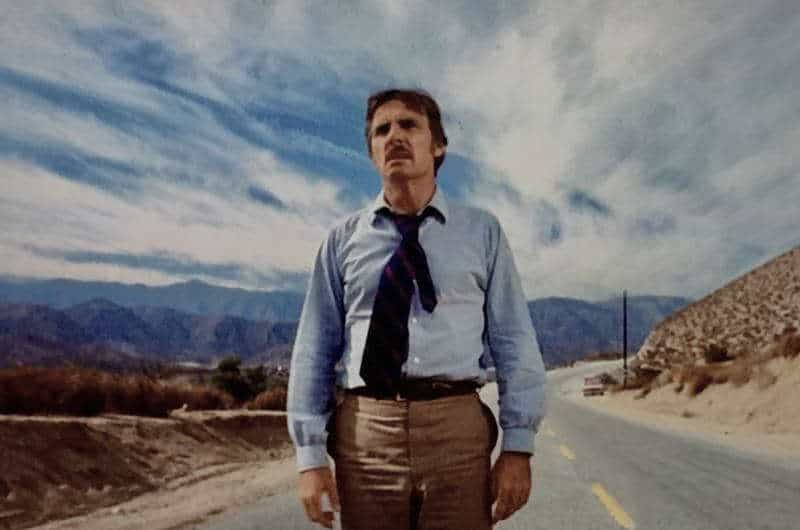

LOCATION

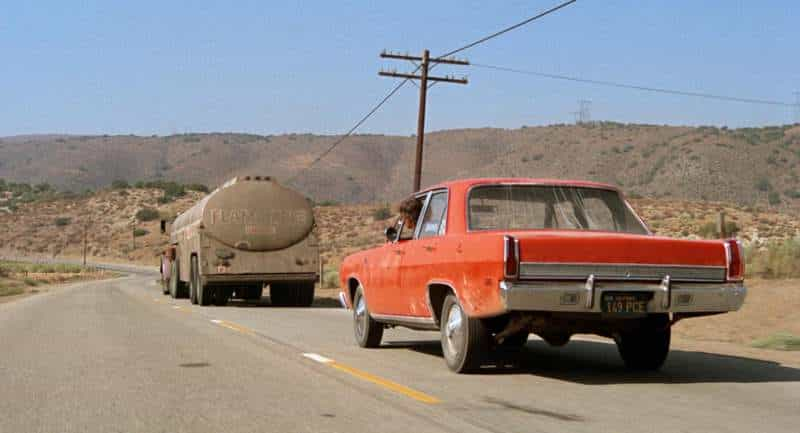

Northeast from Los Angeles, California. Thelma & Louise country. Even those of us who have never set foot in the USA recognise this distinctive landscape from movies alone.

- Canyon Country, Agua Dulce

- Acton, California

More specifically: Agua Dulce Canyon Road, Soledad Canyon Road, and Angeles Forest Highway.

The film-makers were going for a film which had the feel of Road Runner, the Looney Tunes cartoon which first aired in 1949, featuring a very smart bird and the ever-suffering Wile E. Coyote.

MANMADE SPACES

How to achieve visual interest in such a flat, same-samey landscape? Even at the edge of the desert, there’s plenty to work with:

- The gas stations

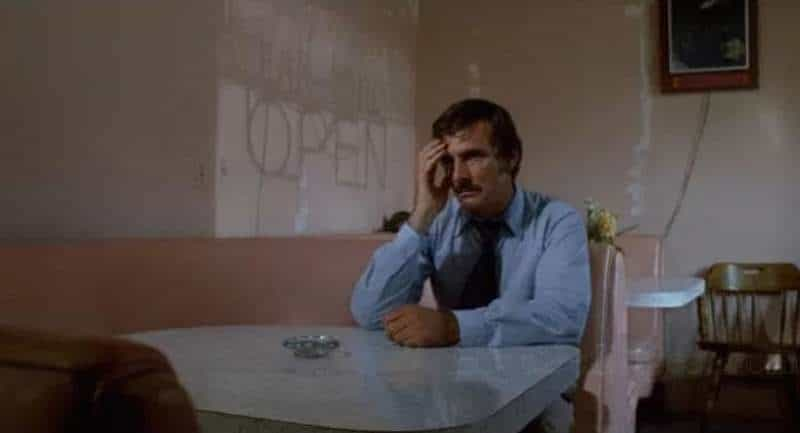

- Chuck’s café (in which signage provides the narrative device of the ticking clock).

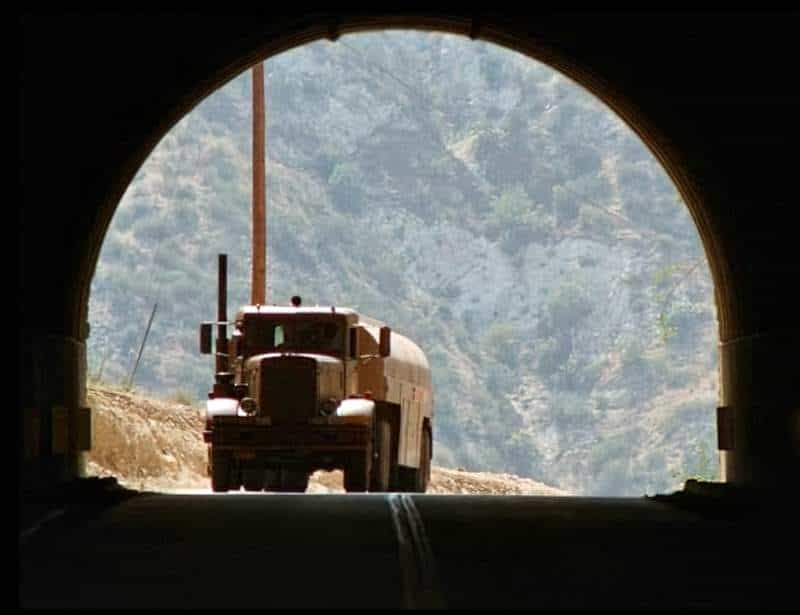

- An ominous tunnel (See: The Symbolism of Tunnels)

Spielberg is well-known for bringing suburban life into his films (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., Poltergeist). The commute by car is also a big feature of suburban life and although Mr Mann isn’t driving through suburbs, the experience is suburban-adjacent.

Matheson and Hitchcock also created stories about strange experiences interrupting the experiences of regular people. There’s no reason why the truck is targeting this guy and not some other guy.

NATURAL SETTINGS

A road heading into the desert

WEATHER

Sunny, glary, dry.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

After going to all the effort of constructing rail across the continent, the USA switched almost entirely to private vehicles as their main mode of transport.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

This is a story about road rage. More broadly, it’s about how people manage to rub along in life while forced to share the same facilities as people we don’t know. When we get into our vehicles, we become somewhat anonymous. More importantly, we feel anonymous, which can change our personality.

STORY STRUCTURE OF DUEL

SHORTCOMING

The ‘victim’ is The Everyman Archetype, as only American white men can be in Hollywood. Even his last name is Mann.

HE LOOKED BACK

But Lot’s wife, behind him, looked back, and she became a pillar of salt.

What does the Bible say about looking back?

Black feminist bell hooks (who recently died) wrote in 1992 about the “oppositional gaze”, which describes an act of rebellion in which a Black person stares back at an enslaver. Because slaves were not allowed to look at their owners, to simply look at them was a charged act.

Whereas hooks was writing specifically about the Black experience in the context of white colonialism, this white man also makes the mistake of making eye-contact with the psychopath driving the truck.

DESIRE

Mann just wants to get to where he’s going, then return home safely to his wife. Eventually, his wish is to stay alive. When he realises the stakes are this high, he makes the decision to sacrifice his car. By this point he’s worried about being killed.

OPPONENT

We never see who is driving the truck. What’s left off the page is more terrifying than what we see. (I believe Wile E. Coyote is driving the truck.)

PLAN

We see Mann struggling to come to terms with his plight. It takes him a while to realise he’s not going to lose this truck. The truck has him in its sights.

Mann will eventually make a plan to destroy the truck, but doesn’t convey this to the audience. We know he’s got something in mind. In audience inferior position, we watch him carry it out. Some versions of this film feature a voiceover in which we hear him thinking, but including this ‘dialogue’ isn’t Spielberg’s choice.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This is, at heart, a cat and mouse story. Almost all drivers have had the experience of passing someone on the highway who doesn’t want to ‘lose the race’, and then makes it their mission to pass you in turn. Then they slow down. If you pass them again, the pattern repeats.

A related phenomenon: Driving below the speed limit, but increasing speed once entering a passing lane, making it more difficult for the cars behind you to finally get past. Most of the time, I don’t believe this behaviour is deliberate, however annoying it is. Rather, entering the passing lane reminds slow drivers just how slow they’re going, and that they could be going faster. So briefly, they do.

This must be such universal highway behaviour, the fight in Duel feels highly relatable, just taken to the utmost degree.

ANAGNORISIS

Sometimes evil has no reason behind it.

Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men has a similar morality. There’s just no stopping some people, in which case, the best you can do is outwit them.

Once Mann realises who he is dealing with, the story can be wrapped up.

NEW SITUATION

Matheson himself changed to ending of his original short story when adapting for teleplay and film.

In the film adaptation, the truck more or less kills itself after Mann drives towards the cliff as a decoy, then jumps out at the last moment, sacrificing his car but not his life. The tanker is unable to stop because of its size, and flies into the cliff, exploding into flame.

The tanker says ‘flammable’ on the back, which viewers see over and over. That it ends in flames feels both inevitable and yet, still, a little surprising.

Influenced by John Ford, Spielberg wasn’t interested in a Big Movie Explosion. The violence should be over in a flash. He wanted a more poetic ending, and that’s what we got.

Spielberg makes use of slow motion to depict this sequence. That’s not what Hollywood wanted, and Spielberg had to fight hard for this lyrical rather than genre ending.

The ending sequence is the only part of the film that Spielberg storyboarded. These days it would be highly unusual for a director to skip the storyboarding part of the process, but that’s not how Spielberg worked. He set cameras along the highway then built the scenes in editing. He also made use of the so-called Bullitt-cam — a specially modified Ford Mustang covered in cameras which was made for a Steve McQueen movie called Bullitt. They were able to manoeuvre this thing between the car and the truck to create some visually exciting sequences.

I’m reminded of Japanese film-maker Hayao Miyazaki who — amazingly — doesn’t know how a film is going to end until he gets there, creating the animation as he goes. I believe this way of working has a palpable effect on audiences.

How to describe the difference? Highly storyboarded work has a deliberateness about it, a technical prowess. Since real life is not storyboarded, directors who simply ‘sit back and go with gut instinct’ manage to create something which feels less fatalistic, less like Hand of God, and less moralistic as a result.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I guess he made his way back home somehow. In the 1970s it was still fairly common to hitch-hike due to the unreliability of cars in general.

I’m guessing the police investigated at some point.

I think Mr Mann will buy a new car. Maybe a smaller one, but still red. To never forget.

REFERENCES

Steven Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film

Steven Spielberg’s long career as a filmmaker began with television. In addition to episodes of popular TV series, he also directed one of the most popular made for television movies of all time, Duel. In Steven Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film Career (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), Steven Awalt describes how the film was made, from its beginnings as a Richard Matheson short story, through its quick production schedule and its popularity on both TV and home video.

New Books Network

Why Every Film Director Owes John Ford

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

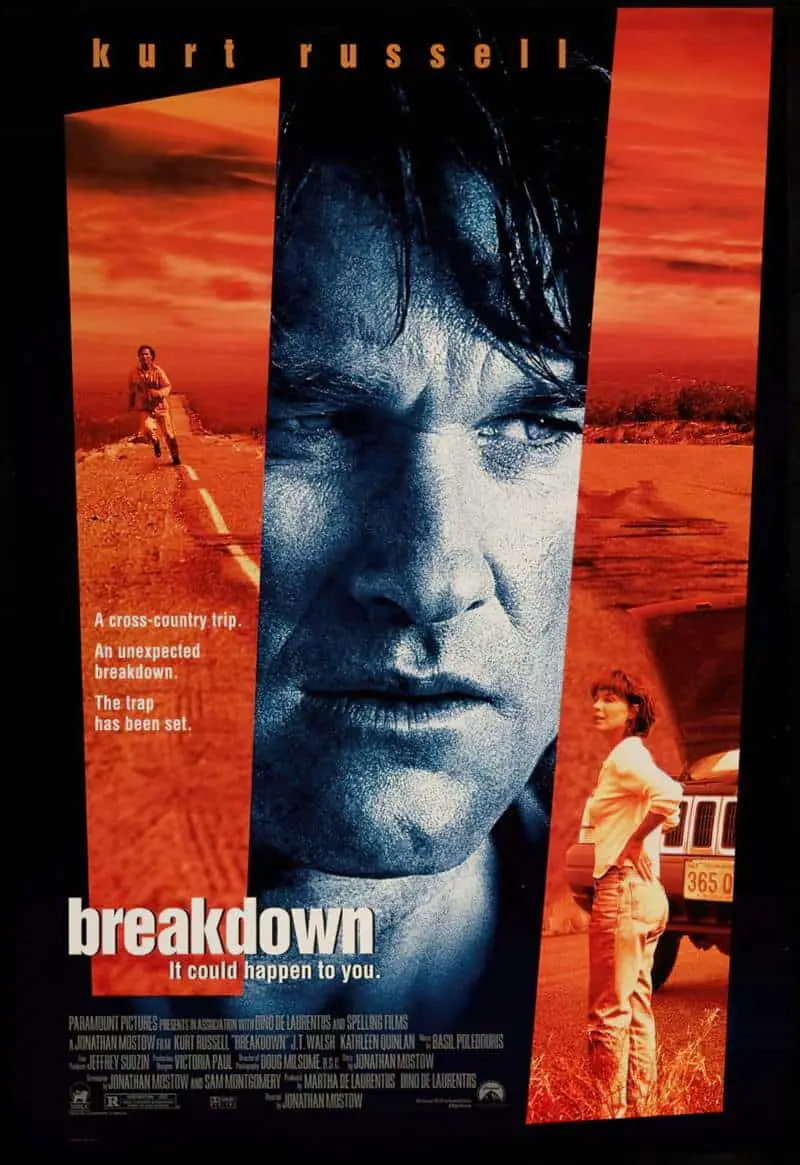

Many movies remind me of Duel, especially the road trip thriller of 1997, Breakdown.

The victims’ car in Breakdown is a red Land Cherokee. The car in Duel is also red. There’s a reason why Little Red Riding Hood was also dressed in red as she made her way out into the big, wide world: Her redness marks her out as a target for predators. Sure enough, when the Breakdown couple is targeted, it is because of their perceived wealth. A couple driving a car like that must have means, and if the wife is kidnapped, the husband will respond to a bribe. Unfortunately for everyone concerned, this couple have overextended their finances and this car is about the only thing they own.

Sometimes it’s just a sequence, like the truck driver scene in Thelma & Louise, which culminates in the duo shooting up the guy’s truck. That sequence is like a mini-Duel plot in its own right. More unfortunately for me, any big rig driving like a nutter also reminds me of Duel.