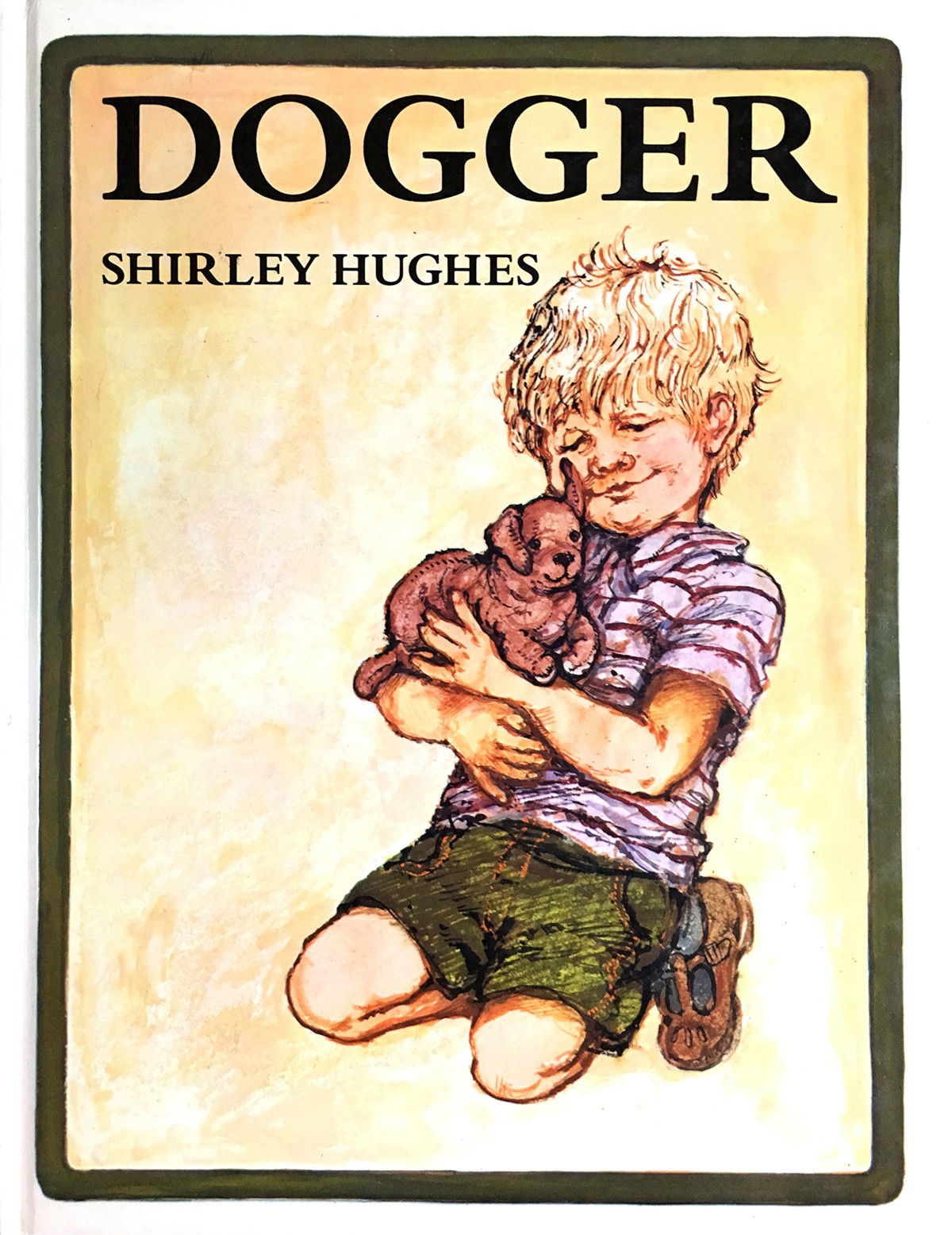

I don’t remember seeing a pristine copy of Dogger, ever. Our own copy as a child had been cancelled from a local library and was covered in yellowing sellotape. I still have that copy. Many years later, this is one of my six-year-old daughter’s favourite books. It is also the number one favourite book of the now 13 year old who waits at the same bus stop. In short, Dogger by Shirley Hughes is a timeless classic. What makes it so good?

PLOT OF DOGGER

The plot of this story is surprisingly complex, though 100% pulled off by Shirley Hughes: A boy goes with his mother to pick up his big sister from school, loses his precious toy dog, then when he goes back to school the following day for the fundraising fair, he sees the dog for sale at a toy stall. Before he can buy the dog back a little girl buys Dogger and takes off with him.

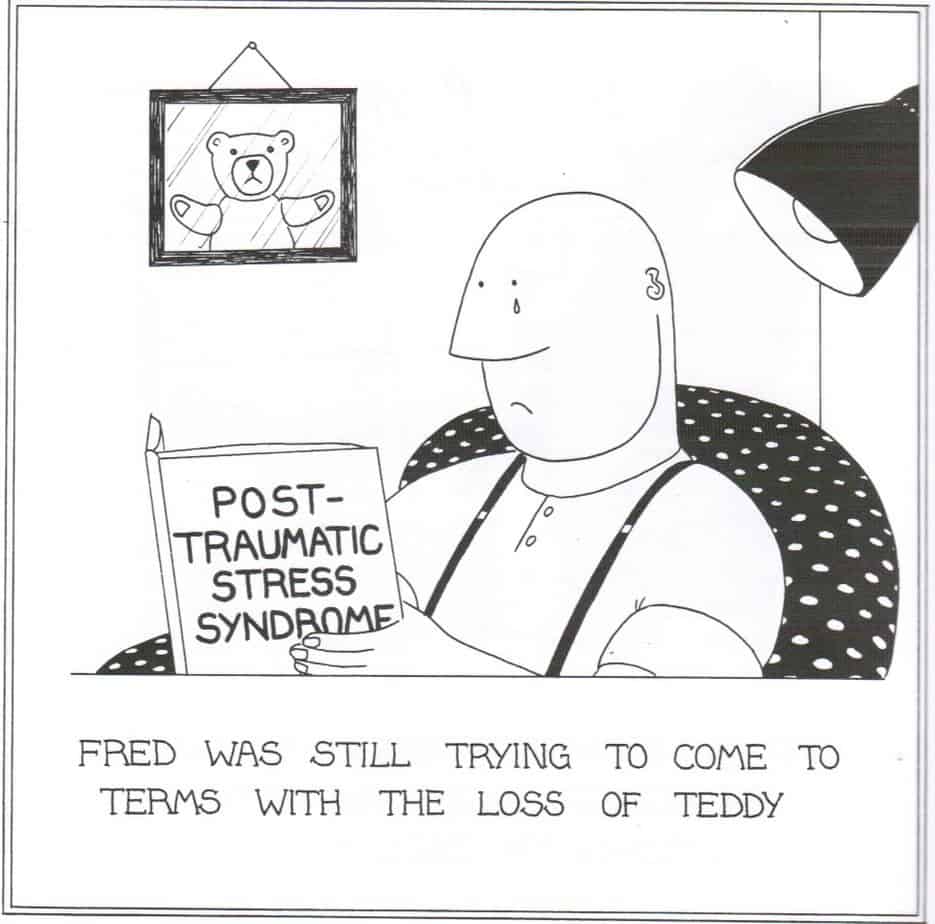

Meanwhile, Davey’s big sister Bella has won a beautiful big teddy. She manages to persuade the little girl to swap Dogger for the big teddy. That night in bed Dave expresses his gratitude to his big sister and his big sister says she didn’t have any room for any more teddies anyhow. All is well with the world.

WONDERFULNESS OF DOGGER

What impresses me is how easily young readers are able to grasp this slightly complex story. What did Shirley Hughes do that a novice writer might forget to do? First of all, the importance of Dogger is established for the reader. Dogger is introduced before any of the characters are introduced.

Next, the full page of illustrations which show Dave tenderly caring for his dog. (I also love this because there are few examples of little boys caring for ‘dolls’ in children’s stories without it somehow being ironic or a reason for being bullied.)

Next the reader has to see that Dave took Dogger to school. Note that the reader is both told and shown the way Dave ‘pushed Dogger up against the railings to show him what was going on’. As small as these details seem, this is the sort of thing that readers absorb subconsciously. We know on subsequent readings that this is how Dave lost Dogger. (By dropping him, or something.) Not only is Dogger’s presence underscored in both the text and in the illustration, the sentence about Dogger being pushed up to the fence is the last sentence on that page. Sentences which come last inevitably carry the most weight.

Next is the scene in which the ice-cream van pulls up. Bella is excited and the children are bought two ice-creams, which Dave must share. Not only has the fictional Dave been distracted — the young reader has been, too. We are now fed detail which is important in the moment: ‘Joe didn’t have a whole ice-cream to himself because he was too dribbly.’ Apart from providing a lovely distraction to both character and reader, this detail is just the sort of thing a child like Dave would remember. ‘Joe kicked his feet about and shouted for more in-between licks.’ I love the phrase ‘in-between licks’ — a neologism coined by a youngster, because to him it is a thing.

Expressed in few words, the realisation that Dogger has gone dawns slowly on Dave, which avoids the need for that dreaded word ‘Suddenly’. The slow realisation fosters more empathy, somehow:

At tea-time Dave was rather quiet.

In the bath he was even quieter.

At bed-time he said:

“I want Dogger.”

But Dogger was nowhere to be found.

The look on Dave’s face is a mixture of bewilderment and distress.

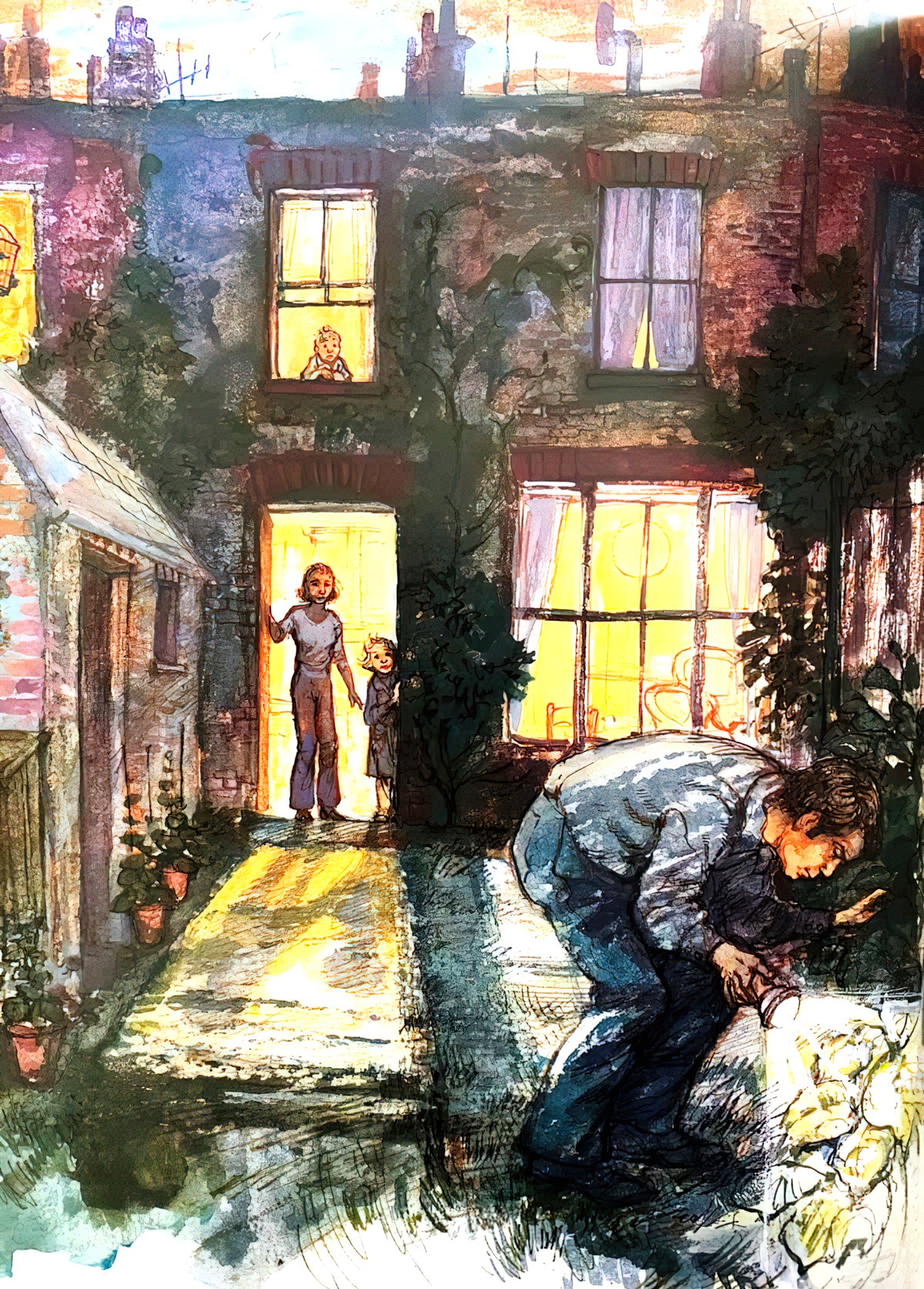

Next we see a variety of scenes in which the whole family looks for Dogger. Something I learned from writing The Artifacts is that both child and adult readers of picture books very much expect the adult caregivers to be kind people. The fact that the whole family is prepared to look for Dogger shows that Dave is cared for by a loving family.

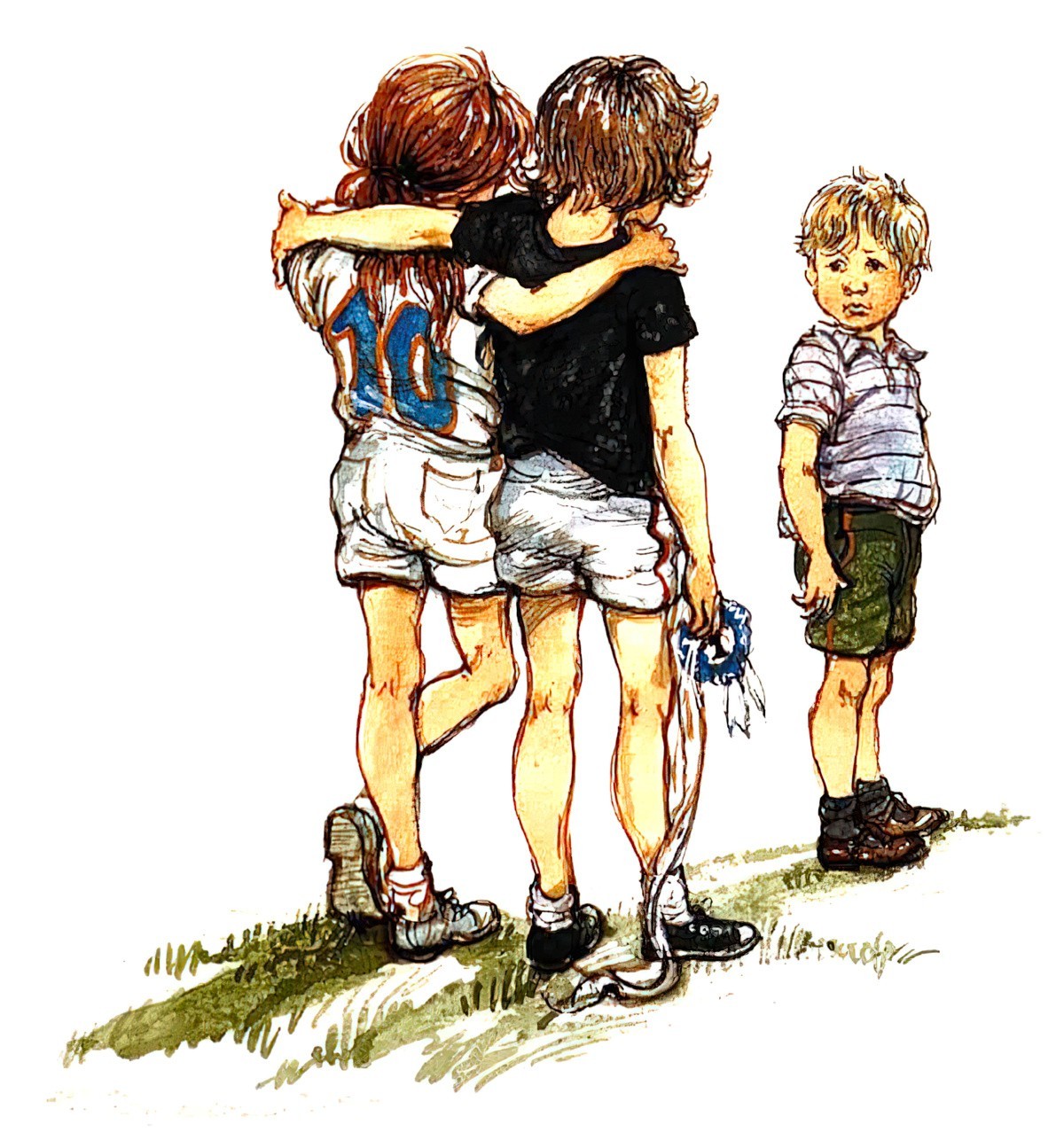

Whatever other calamity has befallen him, this is fundamental, and important when writing marketable picture books for the youngest children. The kindness of Bella is introduced here when she spends time looking through her toy box, then lends Dave one of her own stuffed toys.

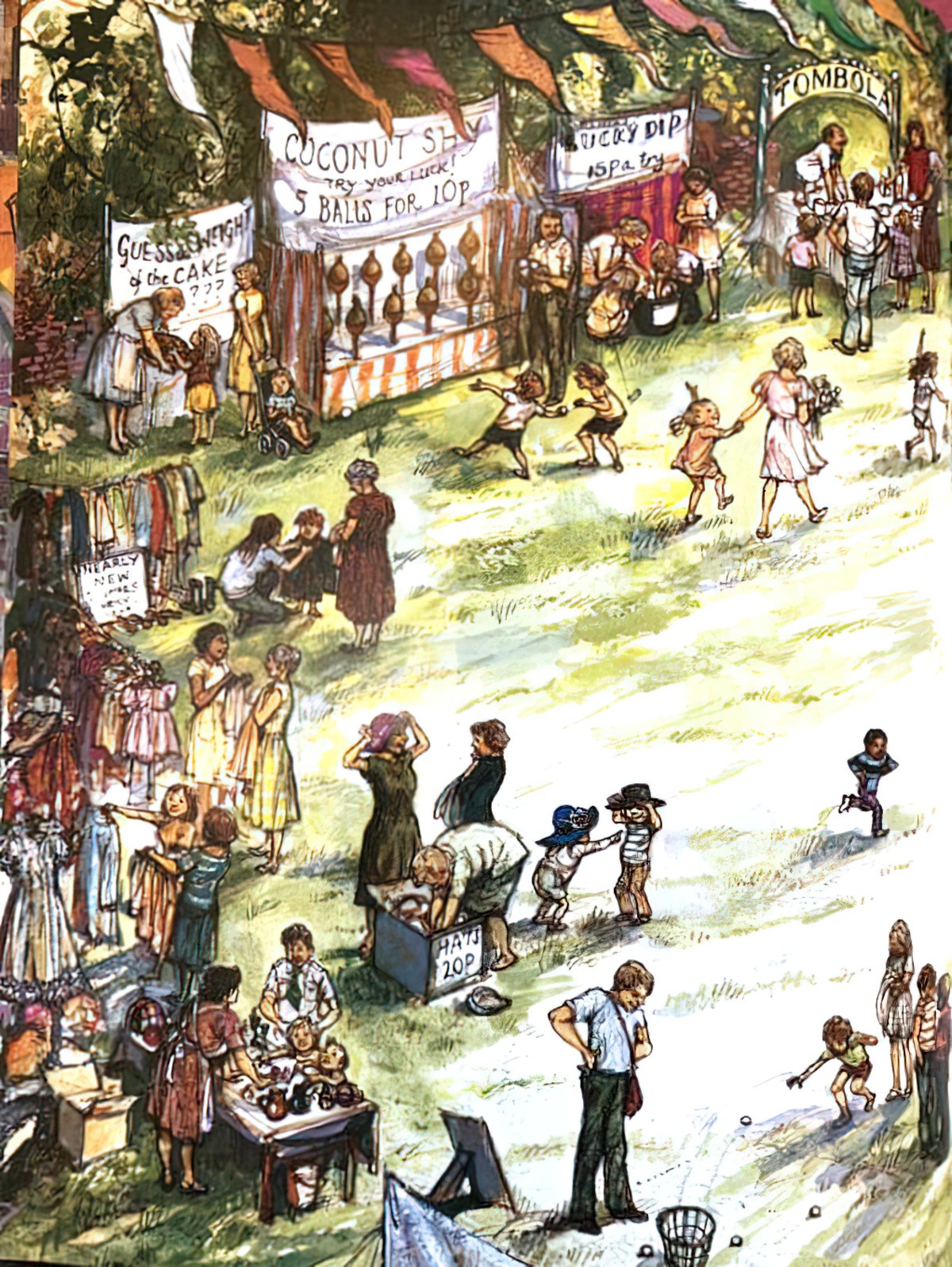

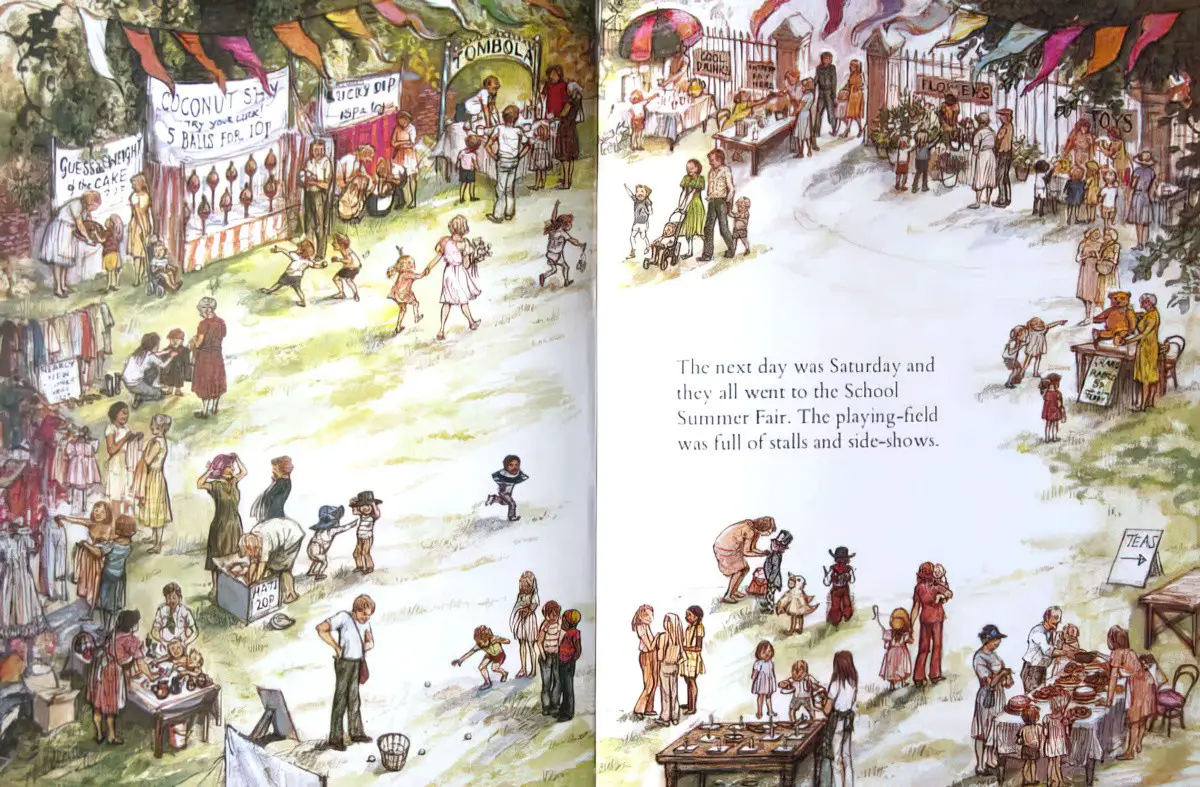

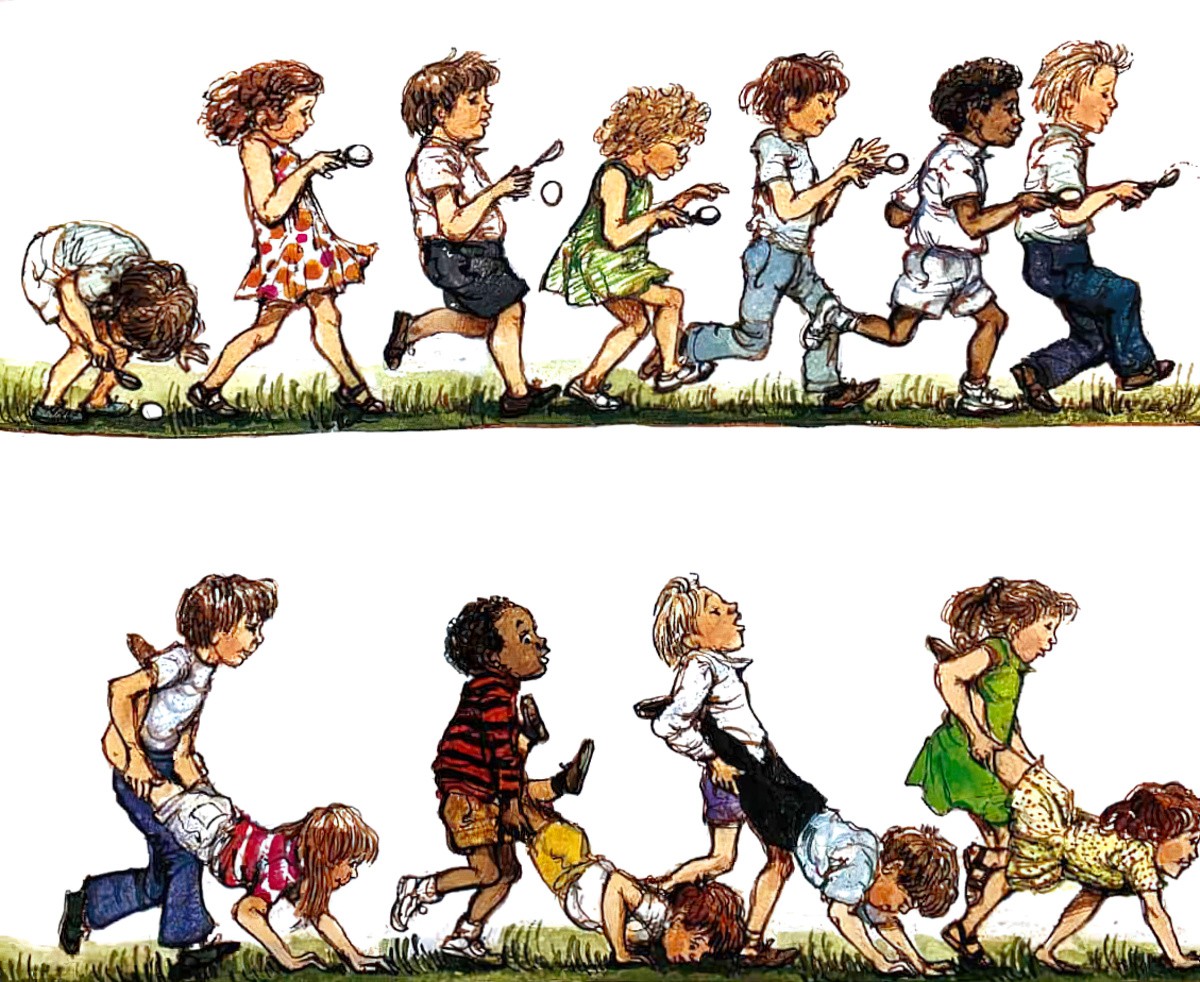

Now that the story is set up, Shirley Hughes makes good use of the rule of three, with a sequence of three embedded into another sequence of three. The family goes to the fair:

There was a Fancy Dress Parade.

(Turn the page)

- Then there were Sports, with an Egg-and-Spoon Race—

- a Wheelbarrow Race

- and a Fathers’ Race.

Bella wins a race

Bella wins first price in a raffle

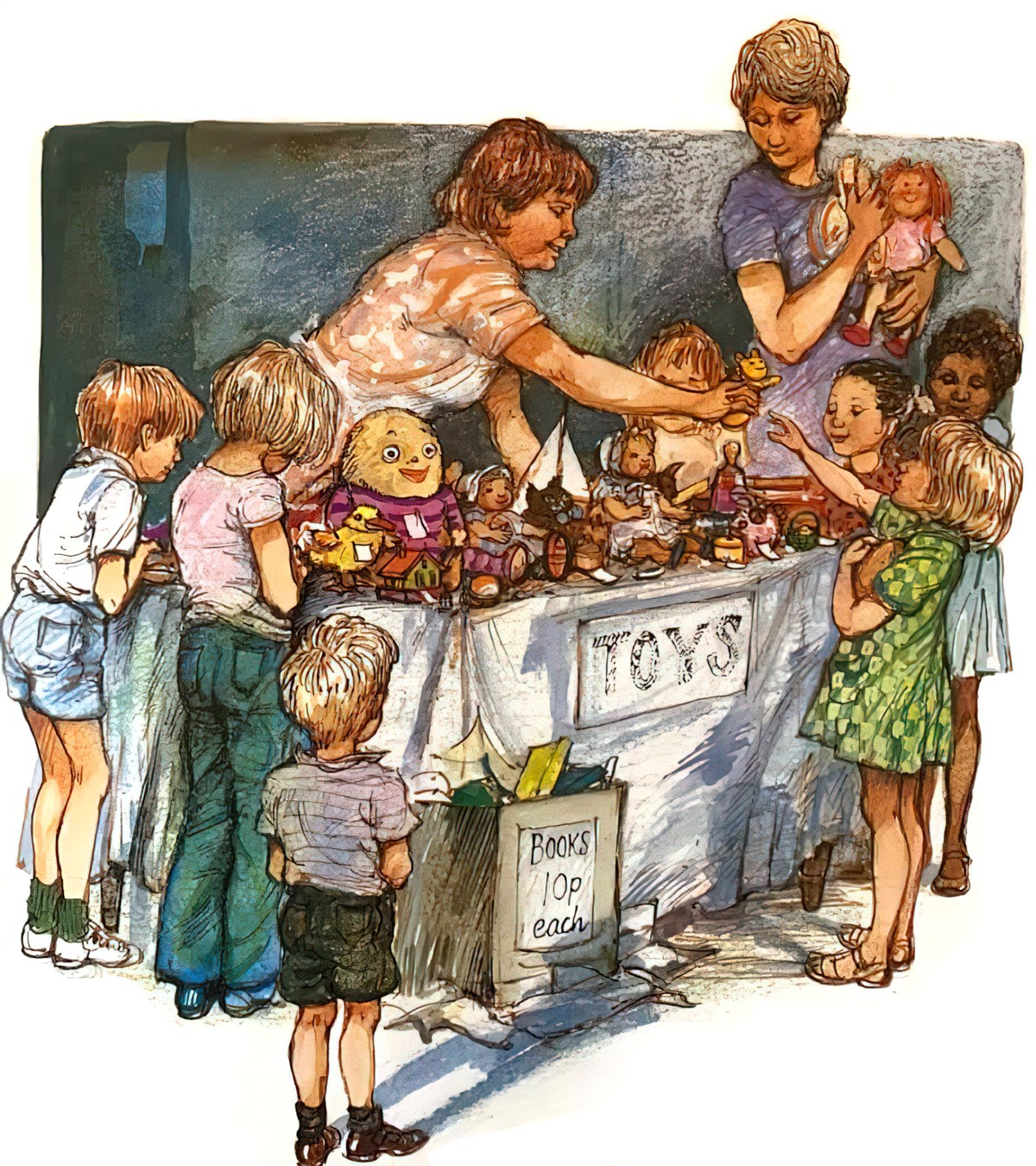

Then Dave comes to the toy stall, which kicks off another sequence of three. After seeing Dogger for sale he is thwarted in his attempts to get Dogger back:

The lady isn’t listening to Dave trying to explain

He doesn’t have quite enough money to buy him back

When he tries to find his mother and father he can’t find them in the crowd.

Each of these events will evoke a lot of empathy for Dave. Three is a perfect number of obstacles, because by the third obstacle the reader is clear that getting Dogger back is going to be no simple matter. (After all, that would make for a lesser story.)

So Bella saves the day, and the reader is taken back to the bedroom we saw at the beginning of the story.

This makes for a perfectly circular plot and an excellent bedtime story. Bella is turning somersaults, endearingly, and reassures Dave that she didn’t like that big teddy anyway because ‘his eyes were too staring’. Again, this is a beautiful use of childlike vocabulary, and the reader is left with warm feelings towards both Bella and Dave. The wordless final image shows the bedroom from the very same angle as the first view of the bedroom, with both children fast asleep. Dave is cuddling Dogger.

Note that at no stage did an adult jump in to save the day. Nor was an adult unrealistically cold — the lady at the toy stall genuinely didn’t understand what Dave was trying to tell her. This is a beautiful example of a story about an everyday event and everyday children. Although a possible moral might be, ‘Be nice to your brothers and sisters,’ Hughes avoids painting Bella as some sort of self-sacrificing do-good character by having her say that she never really liked the big teddy anyway.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF DOGGER

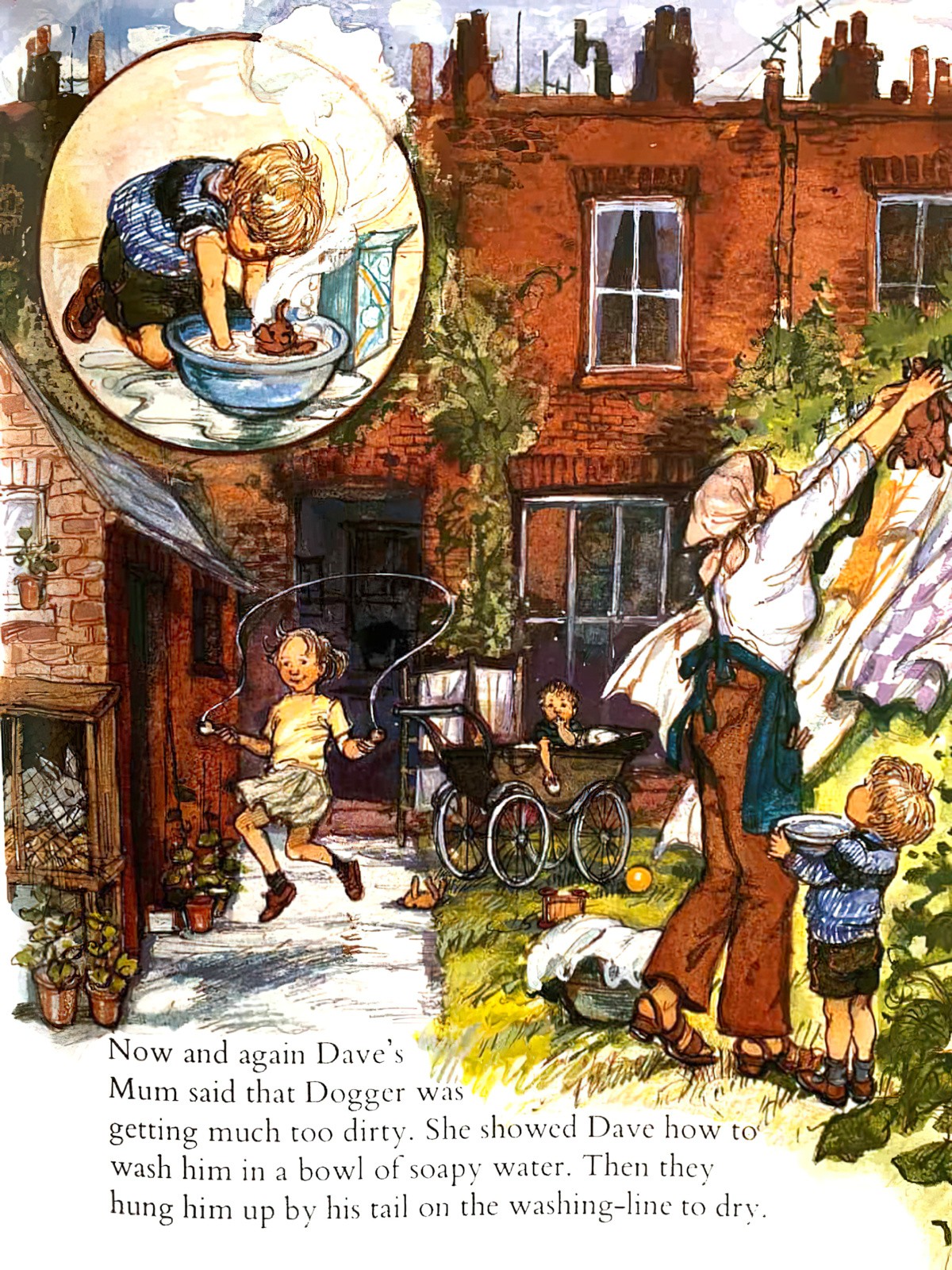

An aspect I appreciate about Shirley Hughes’ illustrations is that they have an ‘everyday griminess’ to them. The children’s bedroom is ‘lived in’, with toys and clothes strewn onto the floor. The homes of Hughes’ characters are the sorts to have overflowing baskets of laundry sitting on the floor, the dishes waiting to be done, toys lying around to be stepped on. Reading this story as an adult, it’s reassuring to see my own house depicted in literature, and the thing about child readers is they tend to love their own homes and don’t aspire for Pinterest levels of perfection.

Hughes’ characters, too, have a ‘homely’ look to them. Even the faces of the children are rendered with inky lines that almost makes them look like old people. Hughes was definitely not a part of the new media trend, in which it is thought that children are drawn irresistibly towards characters with big eyes. What stands out to me reading this story from 1977, the height of second wave feminism, is that the character of Bella — apart from her feminine name and use of ‘her’ — looks no different from a boy. Comparing Bella to modern depictions of girlhood in picture books, today’s young readers are used to the convention that girls must look a certain way: They’ll probably be wearing an article of clothing that is pink. If represented by animals, the female animals will have heavier eyelashes, redder lips or a bow on their head. Yet apart from pink pyjamas, Bella is dressed androgynously — her femaleness is not important to the story — she is first and foremost a kindly older sibling, and I really appreciate this about the character.

As a counterpoint, the little girl with the bow in her hair and the dress behaves like a spoilt brat, with no empathy for Davey who has lost his precious toy. This little girl is a Spoilt Brat Trope, drawn to pretty and new things, and therefore assuaged with the promise of owning a brand new teddy bear. It does concern me slightly that the spoilt brat trope is usually a girl dressed like this which — Bella notwithstanding — can sometimes morph into femme phobia. This is a minor concern.

Shirley Hughes is especially adept at drawing complicated, crowded scenes from a birds’ eye perspective. She demonstrates her skills here by offering readers a view of the fair from above. I’m not sure why birds’ eye views of scenes are so intriguing, but it may partly because children see the world only from a very short position. Seeing more, even from the shoulders of a parent, is a novelty.

The passing of time is often depicted in words, even in picture books: After dinner, before bed, and indeed that technique is utilised here: ‘Now and again Dave and Bella’s mum said that Dogger was getting much too dirty./One afternoon Dave and Mum set out to collect Bella from school.’ But Shirley Hughes also makes use of the visual chronotope, in which the reader sees several scenes, like different frames in a film reel, and is expected to understand that these are not the same-looking characters doing different things, but the very same characters depicted at different times. Below is a visual chronotope of Dave playing with Dogger, quickly establishing to the reader how very important this toy is to his young owner.

Notice, too, the use of an inset image. This is a useful technique to be aware of when needing to create stories for print books, in which stories must fit onto exactly 32 pages. But there’s more to it than that. The inset image of Dave washing his dog links the idea to the mother hanging Dogger on the washing line. Like a paragraph explaining a single idea, this page depicts the single idea of Dogger being washed.

SEE ALSO

If you enjoy the illustrations of Shirley Hughes, you may like to check out watercolours by John Lovett, Australian artist.

If you enjoy the loose watercolour work of Shirley Hughes, check out illustrator Victor Ambrus, whose village below reminds me somewhat of a Shirley Hughes high angle view, as seen in many of her picture books.