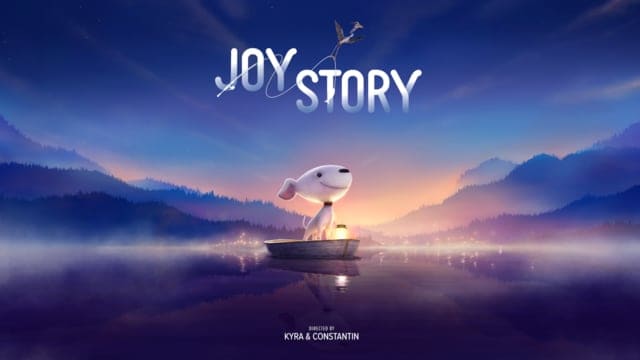

Joy Story is the perfect short film to teach kids story structure, focusing on character empathy and anagnorisis. This story is also interesting in the way it handles gender.

Story Structure Of Joy Story

SHORTCOMING

This story has a clear main character — the dog. I guess the dog’s name is Joy. Which in the West, at least, codes her as feminine. Interestingly, Joy doesn’t have any clear feminine markers. (I suspect Disney/Pixar and Dreamworks would have given her thick eyelashes and ‘feminine’ shaped eyes.)

As Joy steps onto the fishing boat, she shows caution. Her psychological shortcoming is that she’s a little scared of being on boats. While this doesn’t directly relate to her character development (the shortcoming usually does), this makes Joy relatable to viewers.

DESIRE IN JOY STORY

Joy — like most dogs — wants to please her owner. This means guarding the fishing bait worms from the heron.

OPPONENT

An audience is like ducklings — we tend to fall in love with the first character we see. With Joy set up so swiftly and clearly as the main character, the appearance of the heron marks Heron out as opponent. Joy wants to protect the worms. Heron wants to take the worms. Their desires are in direct opposition, making them ‘opponents’.

We do see the heron very early, but it’s easy to miss. The birds fly past in the distance. We’re not supposed to focus on the birds at this point — nor are we supposed to be surprised when a heron turns up. Casual mention of an opponent before the opponent is properly introduced is a good technique, and one much used in murder mysteries.

The camera work helps the audience to regard Heron as the baddie. The camera pans from the feet, sliding up, gradually revealing more as if in a horror film. The low-angle shot of Heron, seen from Joy’s point of view, makes the bird seem powerful and scary. The character design, too, encourages empathy with Joy — while the heron is more naturalistic in proportion, Joy’s head is literally more massive than her entire body. The heron’s eyes look scary. Both characters have ‘humanised eyes’, but the heron’s pupils are very small and instead of white around the pupil, she has yellow. Less human means more scary, to human viewers. Joy has large pupils, with white around the iris so we can tell where she is looking. In lots of character designs with dogs, dogs are given eyebrows. Joy has an expressive brow, but without actual brow hairs. She does have an unusually human mouth, however, with a full set of human teeth and lips which smile and frown.

On the topic of character design, notice the owner has no eyes at all, hidden beneath his bushy brows and a cap. This is a clear signal that the fisherman owner does not play a big role in the story.

PLAN IN JOY STORY

Joy’s plan is to protect the worms from the heron.

The heron has a counter-plan which is in direct opposition — heron plans to steal the worms from Joy.

BIG STRUGGLE IN JOY STORY

After a rule of threes battle, with the final ending in a tug of war, the heron departs, having lost. It seems Joy has ‘won’ and the story could be over. Of course, if the story ended there, it would feel incomplete and unsatisfying. That’s because stories aren’t about winning or losing a big struggle — they’re really about the anagnorisis, and that comes next.

ANAGNORISIS IN JOY STORY

First there is a simple revelation (not the self revelation). The revelation is shown to Joy and to the audience at the same time — another trick writers use to keep empathy with the main character.

Revelation: The heron doesn’t just want the worms. She needs the worms, and they’re not for herself. She is not being selfish after all. She’s not simply stealing worms in order to have fun. This is a life and death situation for her chicks, who can’t swallow big fish. They need smaller food or they’ll go hungry (and die).

At this point, the audience sympathy expands to the bird. Heron and Joy remain in opposition, but the heron is no longer the baddie/villain. Another interesting story technique: Because most baddies are male, and most characters without distinct female markers are considered ‘neutral’ (ie. still male), when we see the heron with babies it functions as a reveal. “Oh, it’s a mother!” we think. Suddenly her badness is downgraded.

(Perhaps people who really know birds may tell the difference immediately, but it’s not easy to sex a heron. The only real difference is in size, and when there’s only one heron, it’s even harder.)

This is an interesting subversion of typical gender roles in story, and only works because audiences have been so thoroughly conditioned to consider any character male, unless specifically told otherwise.

Now for the SELF-revelation. This doesn’t happen until the heron delivers the fish in exchange for Joy’s gift of worms. This is the part where the audience also experiences an anagnorisis, which links beautifully back to the moral argument: Small acts of generosity will be returned to you ten-fold. So be generous, and you’ll get what you desire in the end.

NEW SITUATION IN JOY STORY

Joy only ever wanted to please her owner. When the owner turns round and sees she’s somehow managed to ‘catch’ all those fish, he pats her on the head and she has achieved her original goal. Joy and Heron and owner are happy.

Laughter is not an emotion. Joy is an emotion. Laughter is a criticism we hurl at something we find ridiculous or outrageous. It may occur inside any emotion, from terror to love. Nor do we laugh without relief. A joke has two parts: setup and punch. The setup raises the tension in the audience, if only for a moment, through danger, sex, the scatological—a host of taboos—then the punch explodes laughter.

Robert McKee, Story