“Cosmopolitan” is a short story included in The Best American Short Stories 1998. Author Akhil Sharma (born 1971) was only 27 at the time, so this is an example of an author writing about older characters than himself.

Born in Delhi, India, [Akhil Sharma] immigrated to the United States when he was eight, and grew up in Edison, New Jersey, where he graduated from J.P. Stevens High School. Sharma described experiencing racism in school and in the city: “people cursing at us in the street, and being spat at at school.” Sharma’s teenage brother was in a pool accident, that left him in a thirty-year coma, an incident that forms the basis of Sharma’s semi-autobiographical novel, Family Life.

Wikipedia

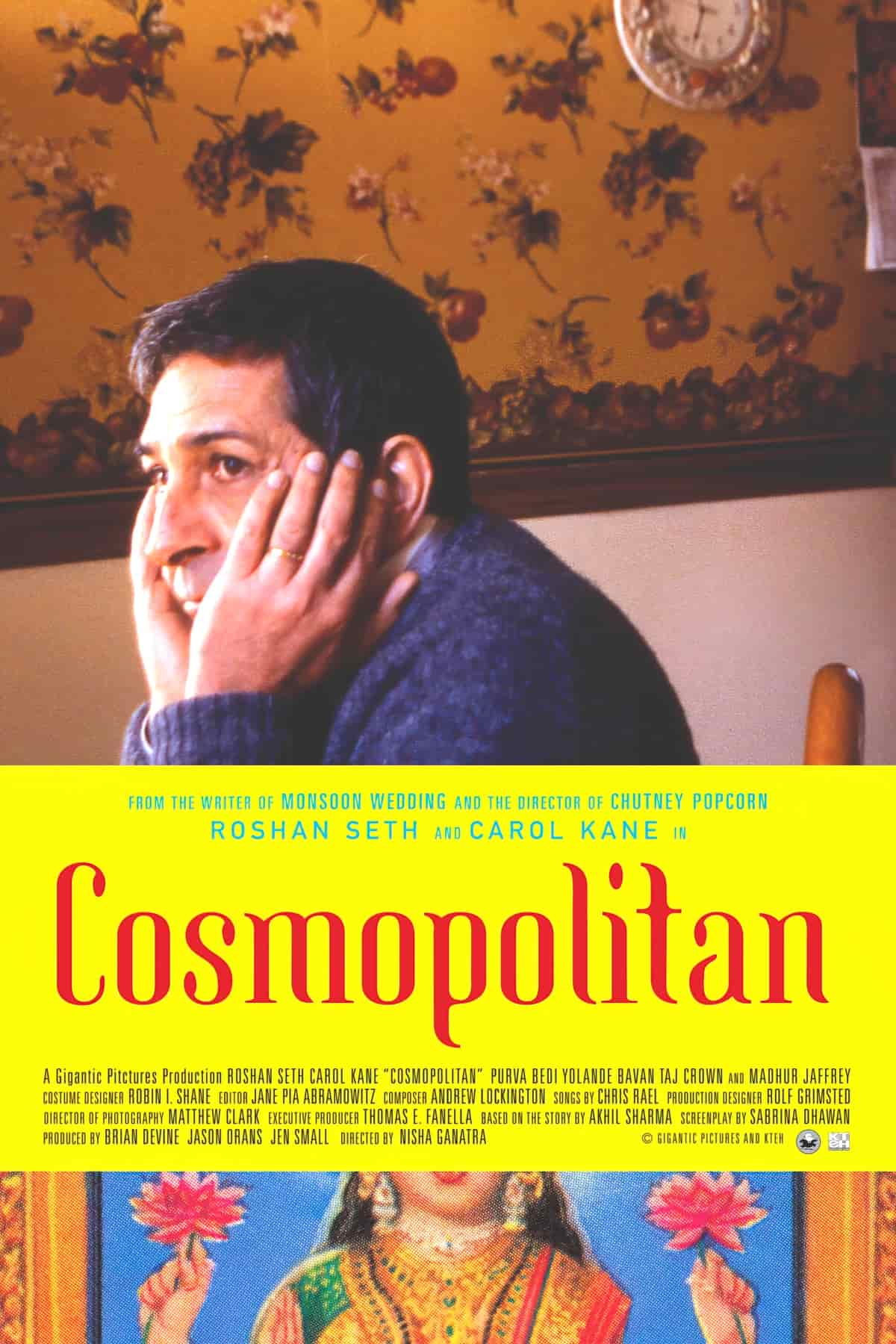

“Cosmopolitan” was made into a 2003 film, and if you’re after a basic plot summary of this story you can find it on the Wikipedia page which describes the film.

SETTING OF “COSMOPOLITAN”

PERIOD

1990s

DURATION

a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

LOCATION

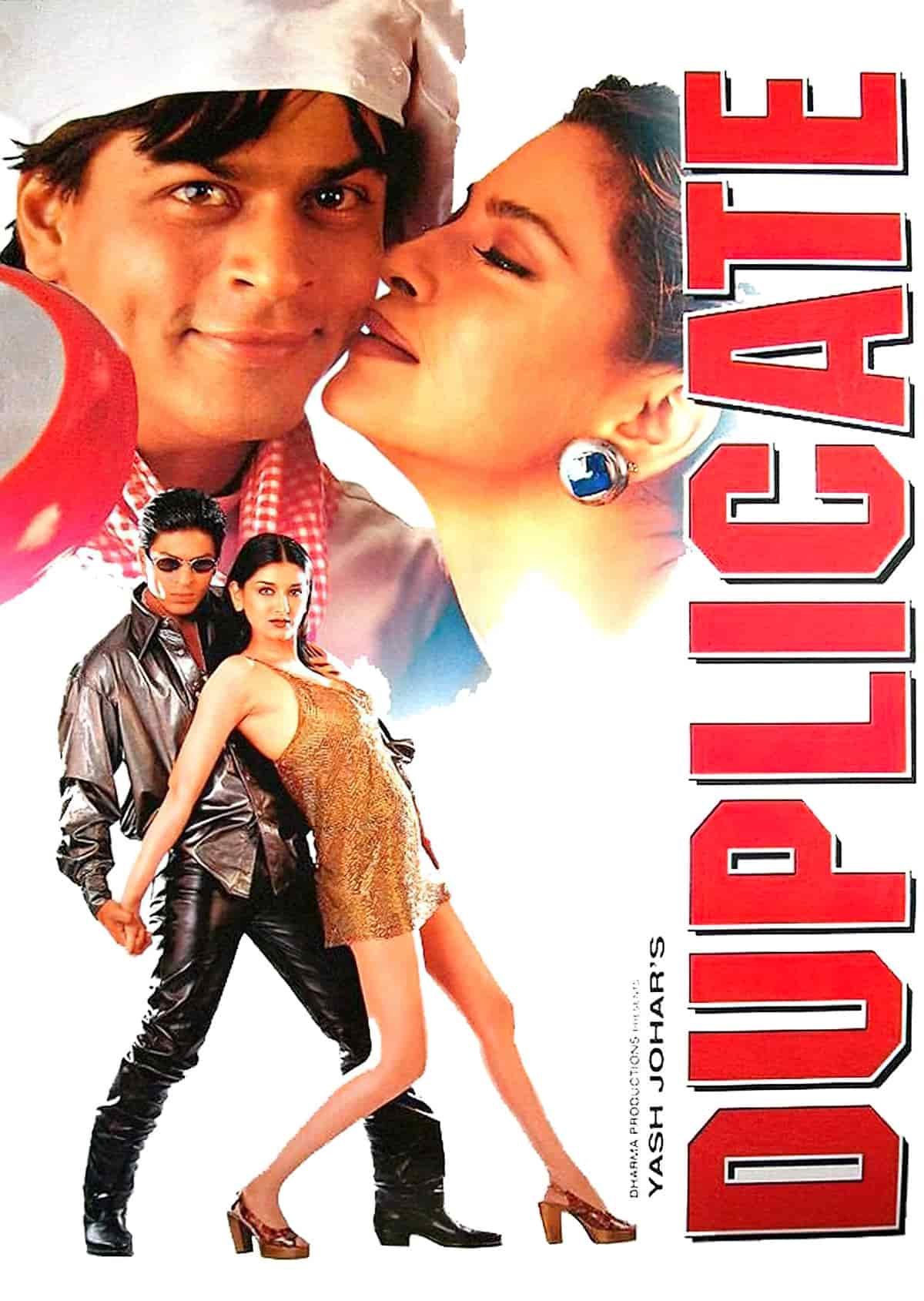

“Cosmopolitan” is set in suburban America. The film adaptation of Cosmopolitan ‘pays homage to classic Bollywood cinema’. So although this story is set in America, it stars a main character who is an immigrant from India. He exists in the middle of two cultures.

Film adaptation aside, how much of the short story is itself a homage to Bollywood? Let’s take a look at some main features of Bollywood comedy:

- Sit-coms dominated from the 1950s to the 1980s.

- Leading men were blundering, relatable characters (low mimetic heroes on Northrop Frye’s scale).

- Frequently, these blundering men tried desperately to appeal to far more sophisticated and beautiful women.

- Stories contained life lessons such as the importance of family.

- Comedies of errors were popular in the 50s-80s era (mistaken identities, often with twins and triplets).

- By the 1990s (and by the time this short story appeared) Bollywood humour had started to change. It follows that audiences were newly attuned to what had previously been normal (and therefore unremarkable) comedy tropes.

- The 1990s featured what some have called ‘harassment comedy’.

- In ‘harassment comedy’, a blundering man harasses a woman and the audience is encouraged to see his unacceptable, stalky interest as love. Akhil Sharma wrote this story around the same time as Judwaa came out (1997). Judwaa is a stand-out example of a Bollywood movie which turns creepy romantic behaviour into comedic fodder. Bear in mind, the same thing was happening in America’s Hollywood. Revisit teen movies from the 1990s and observe a raft of stalking behaviour. Whether comedic or dramatised, harassment as comedy has the same social effect (of normalising problematic behaviours and upholding the gender hierarchy a.k.a. misogyny). Chasing Amy (1997), Never Been Kissed (1999), Can’t Hardly Wait (1998), American Pie (1999), She’s All That (1999)…

- Certain audiences seem to love these kinds of story, which explains why many of those 1990s problematic storylines from Bollywood and Hollywood have become ‘cult classics’.

- Both Bollywood and Hollywood moved away from such overt creepiness at the turn of the millennium. In Bollywood, sit-coms with more family values made a comeback.

ARENA

Two houses, near enough so occupants can see each other. Gopal drives to the mall for a haircut, but instead of going straight there, takes the long route via ‘the lake’.

I interpret this laughable circuitousness as commentary on the outlandish plots of Bollywood film.

MANMADE SPACES

The American suburbs, which often includes a trip to the mall when the author intends to emphasise the ‘suburban-ness’ of the setting. Gopal buys a Cosmopolitan magazine at a CVS (Consumer Values Stores). CVS is a pharmacy which sells a lot of other items besides.

NATURAL SETTINGS

The lawn is the suburban proxy for a natural setting (not natural at all, but nature is held up as ideal). Similarly, sex is often said to be a natural act. (It’s not.)

If sex were so natural, it’d be ironic that magazines such as Cosmopolitan (and Bollywood/Hollywood films) exist to show and tell their massive audiences how sex and romance is done.

WEATHER

The inside of Gopal’s house is dark. Yet when he looks through the peephole, outside is bright and sunny. Note the various juxtapositions that run through this story, not least the juxtaposition between dominant Indian vs American cultures.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

To non-Westerners, the lawn (and the lawnmowing) must seem like a ridiculously extravagant thing that rich Westerners have (and do). Why ridiculous? You pay all this money to keep space which is basically a useless monoculture of grass, then once you’ve paid all that money, you have to do work to keep it in check. A lawn is a part-time job, yet Westerners seem to need it. The ritual of lawn maintenance must keep our anxieties in check. (If all is well with my personal lawn, all is well with the world.)

The lawnmower of this story functions as a comedic and American motif and draws attention to the lawn, of course, a motif which relates to the unnatural naturalness of sex and romance.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

By the beginning of the story, the main man’s family have already left him on his own. It’s not immediately clear that they’re not dead. It is later revealed that his wife and daughter have moved away.

This particular story is one of romantic conflict but it’s noteworthy that Gopal Maurya’s family is a wife and a daughter (no other boys or men). He has been let down by women, specifically.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “COSMOPOLITAN”

PARATEXT

TITLE: COSMOPOLITAN

- including people from many different countries.

- (of a plant or animal) found all over the world.

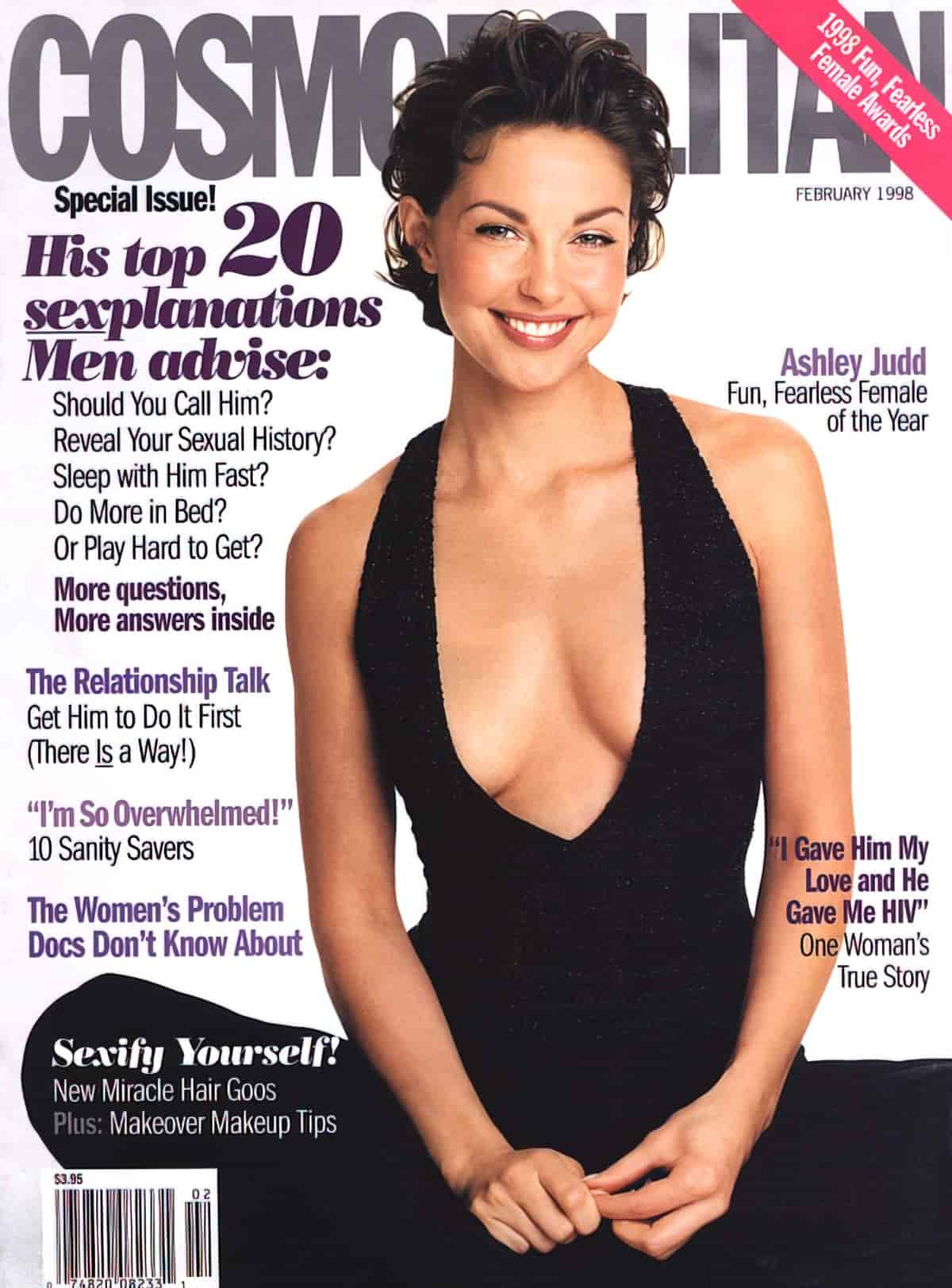

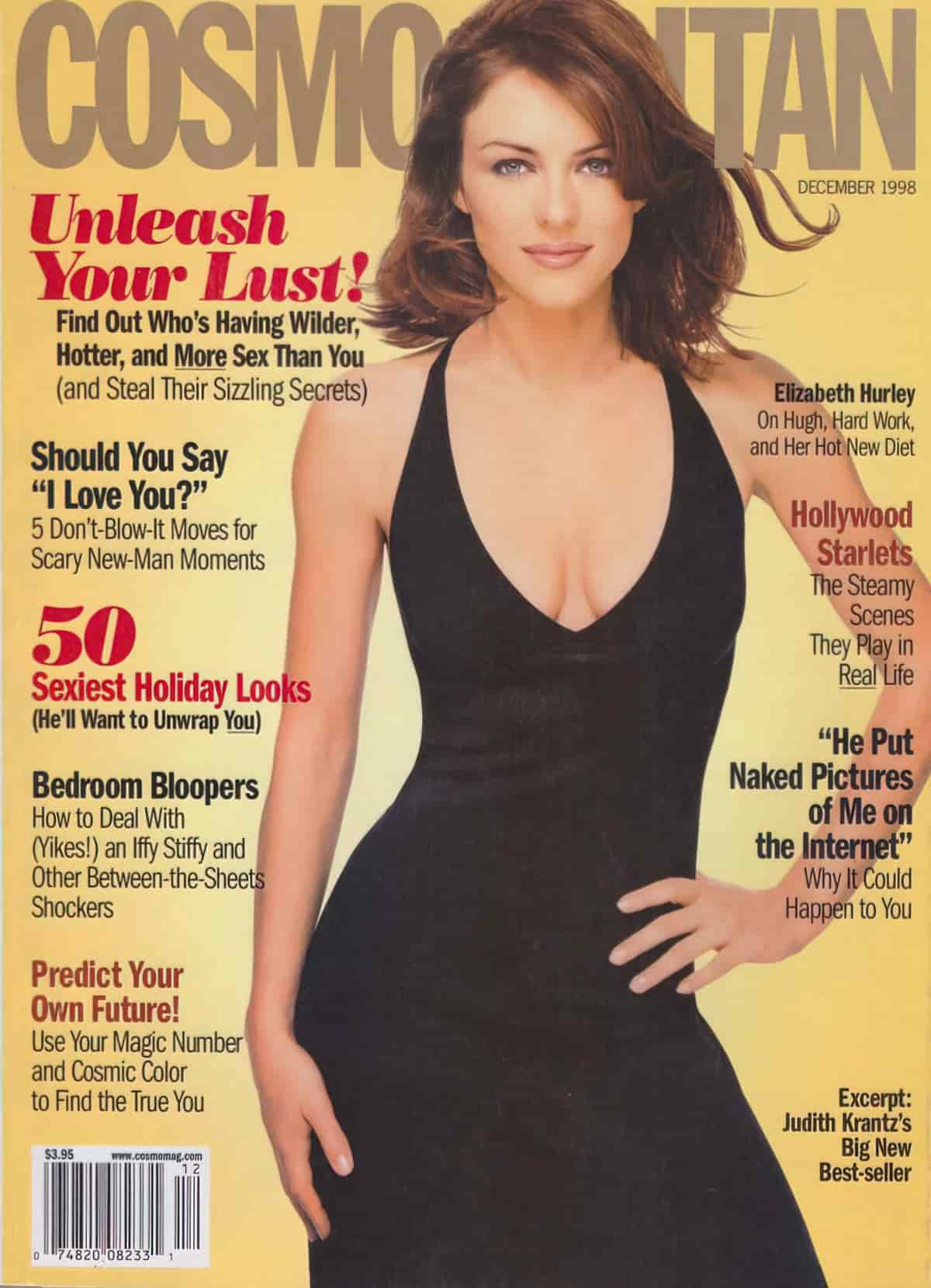

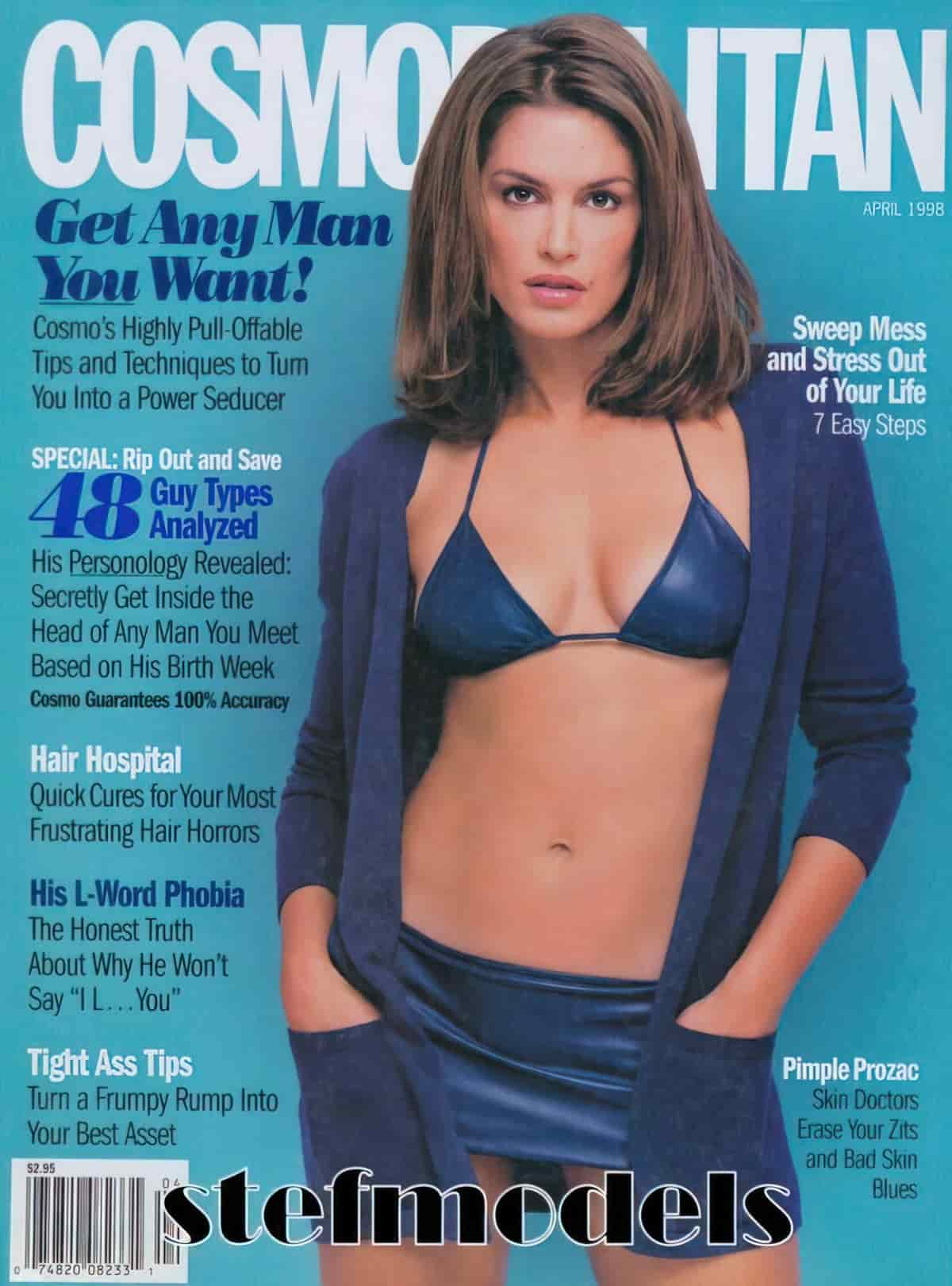

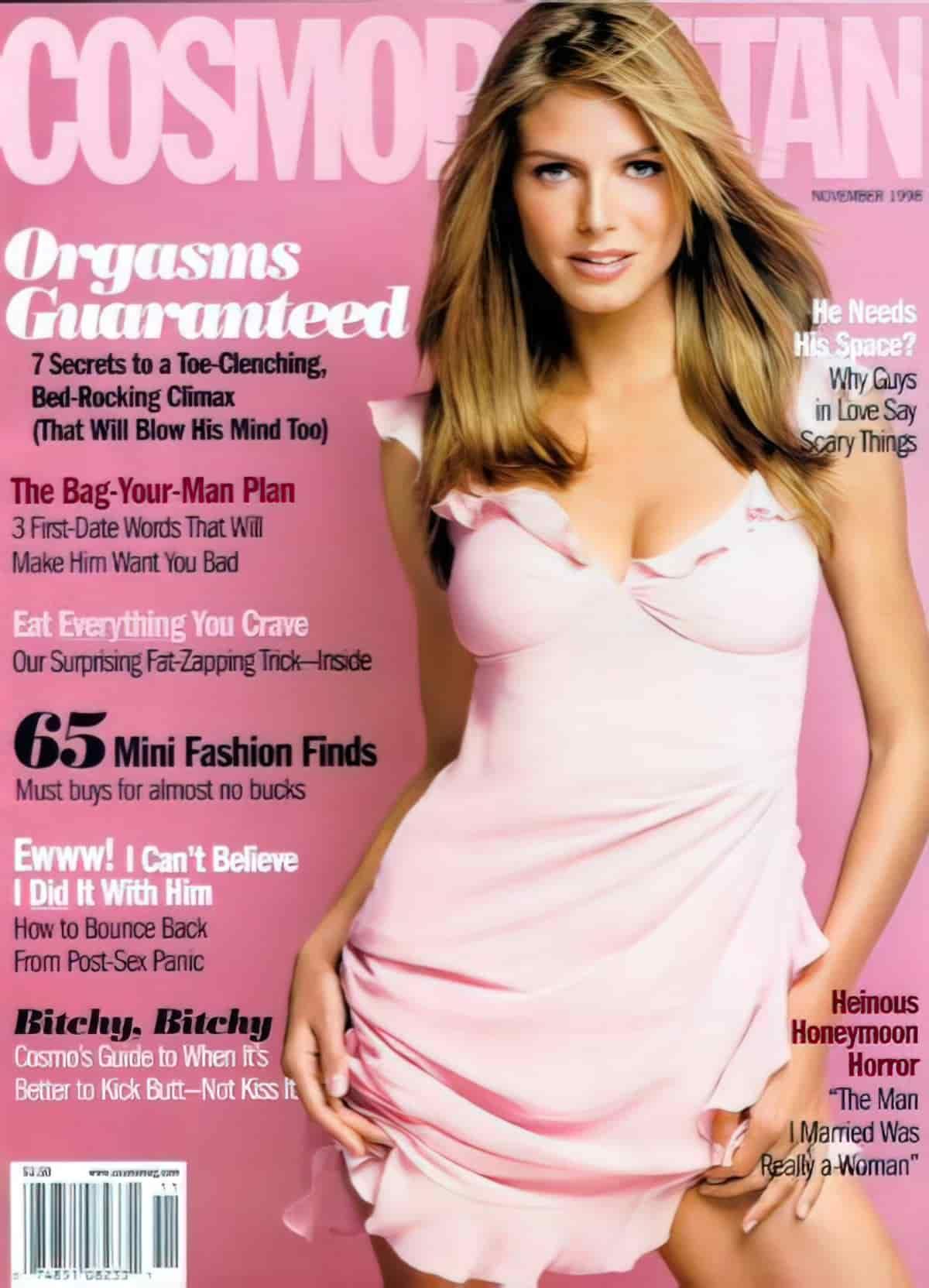

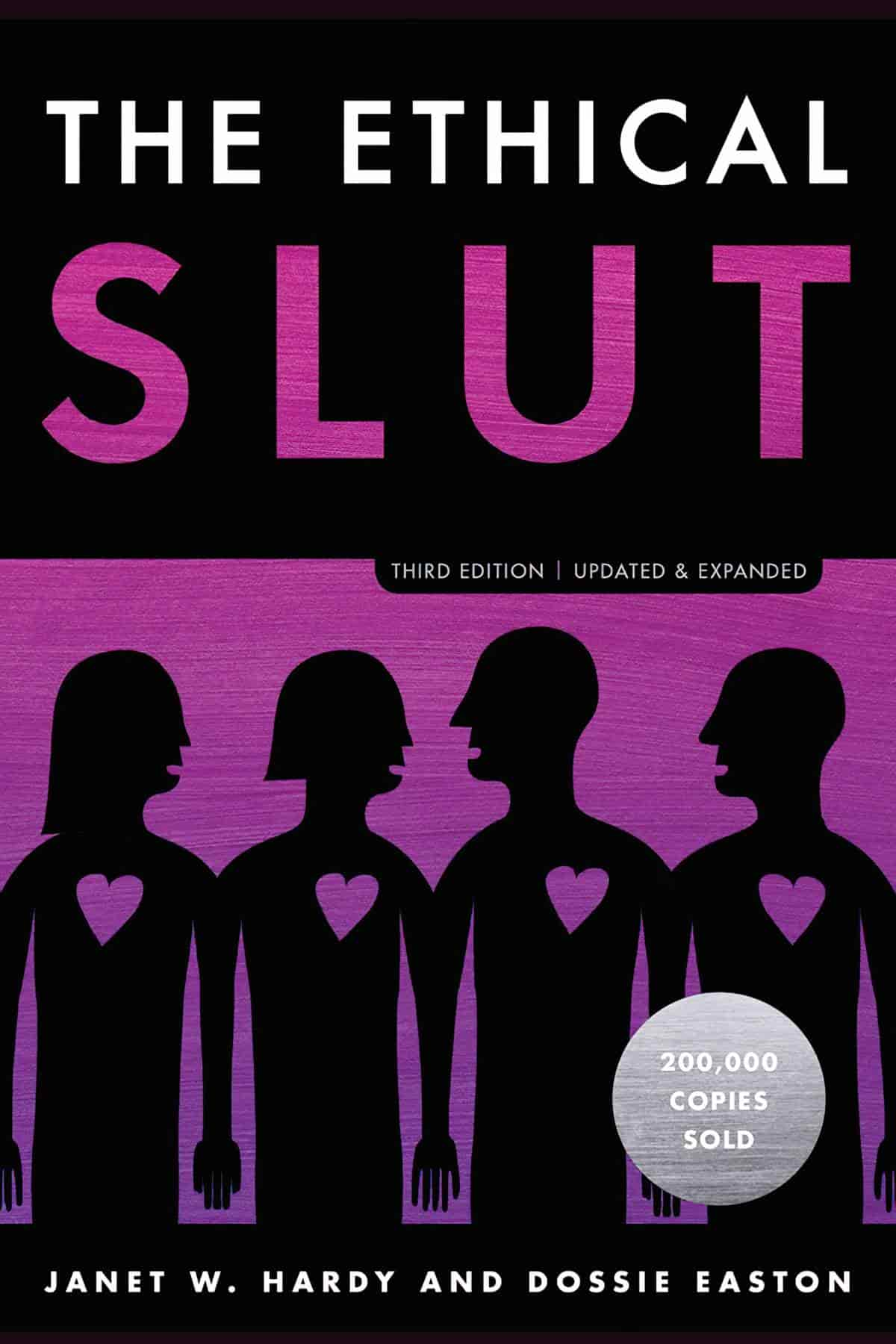

- an American monthly fashion and entertainment magazine for women. Cosmopolitan (often shortened to Cosmo) was first published in New York City in March 1886 as a family magazine. It later became a literary magazine. Cosmopolitan has been aimed at ‘modern, single career women’ since 1965 under the direction of Helen Gurley Brown.

Cosmopolitan is a divisive magazine, lauded by some feminists for acknowledging women as sexual beings, and by some feminists for ultimately being unhelpful to full emancipation by contributing to impossible standards of beauty. Cosmopolitan has also been accused of targeting girls while pretending to attract young women.

In this way, the magazine is as divisive as those 1990s Harassment Plots. Audience members tend to love them or hate them. Then there’s the segment who knows full well how problematic they are, but enjoys them anyway, often arguing that audiences should be treated with respect. (I.e. trust audiences to know misogyny, racism, ableism, homophobia and transphobia when they see it.) Complicating matters: Audiences of primarily women are infantalised more often than audiences of primarily men.

Akhil Sharma utilises both main meanings of Cosmopolitan in this story, and creates a comedic juxtaposition; in this case, the magazine for young women is read by an older man.

SHORTCOMING

When we first meet Gopal he is sleeping during the day and is wearing only underwear and socks. He’s stripped of dignity. This is the author teaching us how to read him: As the classic Bollywood low-mimetic hero.

This is ultimately a story about loneliness. Like boredom in children’s stories, loneliness is the mental state which propels the main character into action. Gopal starts a relationship with someone he ordinarily disrespects.

I’m not sure if the following reads differently due to the #MeToo movement or if readers of the 1990s would have interpreted the following as inappropriate:

Gopal wanted to put his hands on her waist and pull her toward him. And then he realised that he had.

“Cosmopolitan”

There’s a plot line in one of the earlier Desperate Housewives seasons in which a man (only later shown to be harmless) breaks into Gabrielle’s house. Eva Longoria, who played Gabrielle Solis, found this scene far more alarming than the writers did, but played it nonchalantly, as instructed.

Writers don’t always understand a more typically female experience. When Gopal makes his first move (physically) on Mrs Shaw while Mrs Shaw is alone with him in Gopal’s garage, she simply responds with “No. No,” and then laughs.

Is this scene a spoof of the inappropriate forwardness of the bumbling leading men of 1990s Bollywood movies? Gopal’s romantic lunge is certainly reminiscent of the over-the-top physical comedy of Bollywood movies (and also of Desperate Housewives, most notably in the character played by Teri Hatcher, Susan Mayer).

When Mrs Shaw says “Not now” she could be letting him down lightly. She could be giving her neighbour a gentle “No”. But Gopal (correctly, as it turns out) interprets this as a yes, ‘as if the two of them had already made some kind of commitment’.

The third person narration explains Gopal’s ability to switch one woman (his wife of 30 years) out for another. To Gopal, women are switchable. Note that the old switcheroo is straight out of a Bollywood film.

The women of those stories aren’t supposed to care. Therefore, the audience does not empathise with the plight of the women. To the audience, as well as to the leading, bumbling men, the women of these stories are switchable. ‘Womanliness’ becomes the defining (and only) characteristic of any woman character.

Contributing to Gopal’s loneliness:

Most of Gopal’s acquaintances had come by way of his wife.

“Cosmopolitan”

This is surely a critique of the gendered way our society is set up, in which women are charged with the task of maintaining social bonds outside the workplace.

DESIRE

When a woman shows up on his doorstep — a woman he doesn’t know or respect — he is so desperate for female companionship that he immediately sees himself and Mrs Shaw together for the rest of their lives.

‘From behind the curtains he would stare at Mrs Shaw’. This furtive (pervy, stalky) behaviour is also a Bollywood trope.

OPPONENT

ROMANTIC OPPONENT: MRS SHAW

Her colouring juxtaposes against Gopal’s in the most dramatic way possible for a white person:

She was short and red-haired and wore a pink sweatshirt and gray jogging pants.

“Cosmopolitan”

As in many stories, the houses are proxy for the personalities who inhabit them. Gopal at first sees her as ‘dissolute’ due to the various male visitors who come and go.

Although he did not dislike Mrs Shaw, Gopal was irritated by the peeling paint on her house and the seeds sprouting out of her broken asphalt driveway, as if by association his house were becoming shabbier.

“Cosmopolitan”

In Bollywood, as well as in Hollywood, women are distinguished by ‘womanliness’, and secondarily, by ‘what kind of woman’ they are, always in relation to a man: Whore, Mother, Wife.

PLAN

Gopal springs into action as soon as he is presented with a woman, any woman. He makes a move on her (not exactly planned, but driven by his libido and loneliness).

Next he plans to become the fully-functioning adult he was before his wife and daughter left him. He makes an elaborate meal for himself of ‘three dishes and a mango shake’. This, too, is reminiscent of Bollywood. Food serves an important function in Bollywood films:

The meals in many Bollywood flicks serve as important subtexts to stories about identity, place, and family. Or, in other cases, food functions as a straightforward plot device meant to ground an otherwise absurd story (all too common in the world of Bollywood).

Saveur

He buys a copy of Cosmopolitan: Mrs Shaw is American, the magazine is American, and since ‘women’ are switchable and a monolith, he only needs to read an article or two in here and he’ll secure the affections of this stranger. The scripted ease with which Bollywood couples get together is spoofed with the line, ‘All you had to do was listen closely and speak honestly.’ (Note the specifically American twist: Utter honesty in spousal relationships is a Western ideal.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

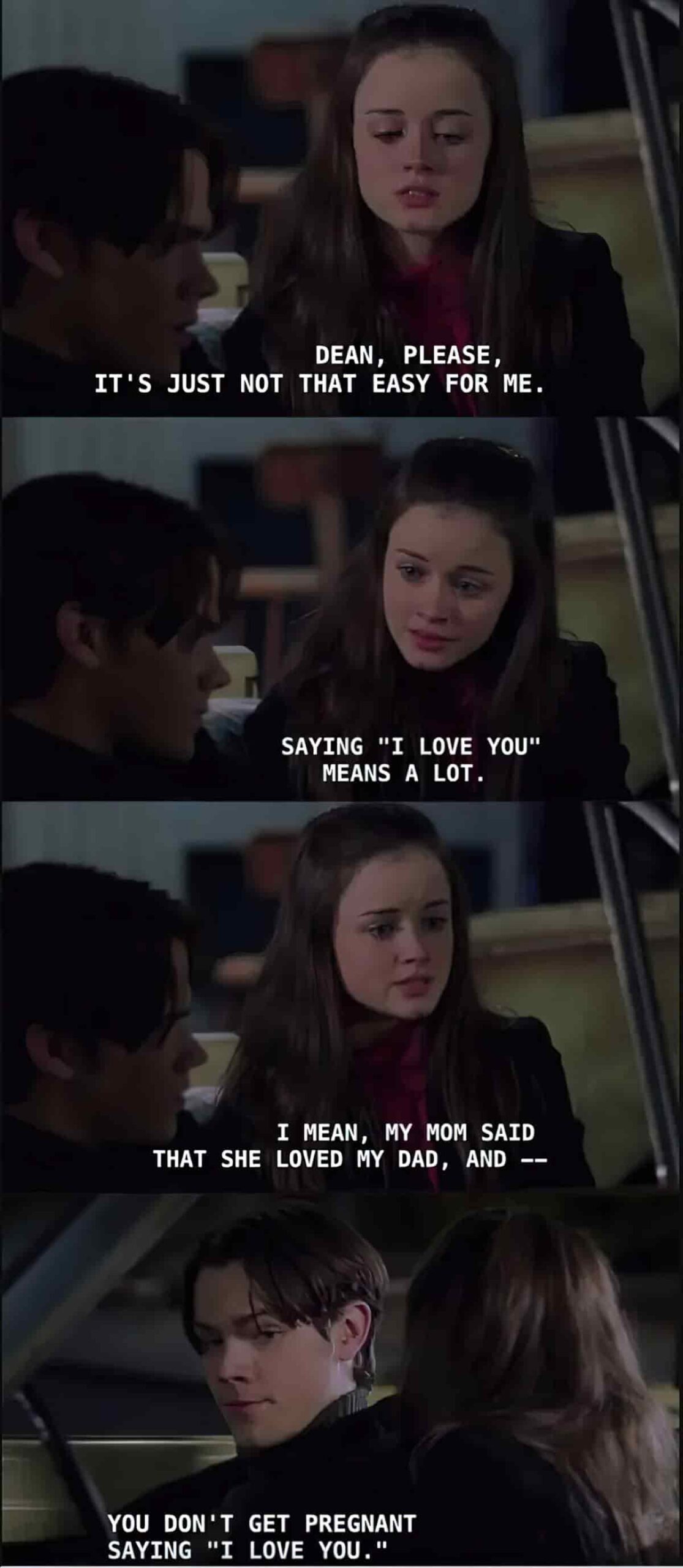

Gopal tells Mrs Shaw he loves her, even though he’s not sure that he does. Mrs Shaw is unable to reciprocate in the moment, then explains why Gopal should not take her reply personally:

To fall in love I think you need a certain suspension of disbelief, which I don’t think I am capable of.

“Cosmopolitan”

Now I think about it, Dean of Gilmore girls is another outworking of the performative romanticism we also see in Gopal. Perhaps you can think of more fictional examples, or examples from life.

Although Mrs Shaw has always been honest about Gopal regarding what kind of relationship she wants, Gopal has been acculturated by a specific kind of Bollywood romance, which we see also in self-help romance magazines such as Cosmopolitan. The narratives around romance — and how things are supposed to pan out — are cross-cultural.

Meanwhile, Helen Shaw seems to have read this book (or could have written it).

ANAGNORISIS

This part of the story starts to flummox and frustrate me.

Gopal continues to feel jealousy. There’s no point at which his jealousy abates. That said, the author keeps readers in audience superior position regarding Gopal’s state of mind, and by the end of the short story, Gopal is more emotionally literate. He is able to name his own jealousy, which is something.

Perhaps this is all the self-revelation we might expect. I feel surprisingly frustrated by it, knowing that in short stories characters don’t necessarily change much.

What frustrates me the most is the scene where Gopal visits Helen after one of her lovers leaves in the middle of the night. When Helen opens her door to him, she recoils, as if expecting to be hit. This is surely a clue that she has just been hit by another man. Also, mascara is running down her face.

Gopal has gone to Helen out of jealousy, and a desire to claim her for himself but he ends up being her saviour — some welcome company after an altercation with a physically violent man.

This reads to me like punishment for Helen, the whore-woman archetype. (If you’re going to have sex with more than one man, you can expect one of them to be violent to you… That sort of thing.)

Is this a continued spoof of the bumbling Bollywood man, who ends up rescuing a damsel in distress entirely by accident and then winning her for himself? If so, there’s no subversion on the highly problematic plots of the stories this one spoofs.

NEW SITUATION

The happily ever after part is, thankfully, lopped off.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

If these people were real, I don’t think Gopal and Helen are an enduring match. Helen is too street smart. She is also streets ahead of him in the emotional literacy department.

RESONANCE

However, audiences clearly enjoy the dynamic of the emotionally adept woman with the inept man (who these days is often coded by audiences as autistic).

To take another example of this gendered romantic dynamic from contemporary pop culture, we have Constance Tucker (Meemaw) and her relationship with Dr. John Sturgis from Young Sheldon.

Helen Shaw and Gopal of “Cosmopolitan” have a very similar relationship. Like Helen, Constance of Young Sheldon likes her hard liquor and her men. She’s quick-witted and highly attuned to other people. She knows exactly who she is and what she wants. More importantly, both of these characters know what they don’t want from a man.

It’s difficult to find examples of romantic couples in which the man is constantly making up for the social shortcomings of his female romantic partner. The reasons are clear: Women are expected to be good at this stuff, whereas men are let off the hook, so long as they’re well-intentioned.

A true subversion of this old story might just be as simple as a simple gender subversion of awkwardness, followed by a happily-ever-after in which the man compensates rather than the other way round.