The Lost Daughter is a 2021 film directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal, based on the novel by Italian writer Elena Ferrante (2015). This is Gyllenhaal’s debut as feature-length film director. I look forward to seeing what she does next.

There’s a great soundtrack, composed by Dickon Hinchcliffe. Gyllenhaal has said that working with Hinchcliffe felt more like working with an actor.

This film also exemplifies why we need more women making films. The Lost Daughter zooms in on the psychological load borne by mothers.

The story asks:

- What makes for a good mother?

- What does mother-guilt feel like, and what sort of outworking might mother-guilt have in a person when left to grow and fester?

- How does society idealise motherhood?

As a concrete example of something Maggie Gyllenhaal did to make the film more relatable to mothers: In the fraught beach scene with the lost little girl, Gyllenhaal pushed her sound designer to make the crying of the child overbearing for the audience. He was tempted to keep it quiet, and unrealistically unobtrusive. Yet every involved parent understands that overwhelming urgency of their own child’s cry. Strangers can block it out, but parents (including highly involved caregivers) cannot. This detail about the perceived volume of crying cannot be known unless you’ve loved, and been responsible for, a child. (Or probably a puppy, to be fair. I feel the same about my puppy’s crying.)

There are various other tiny details in the film which exemplify the experience of being a mother, including:

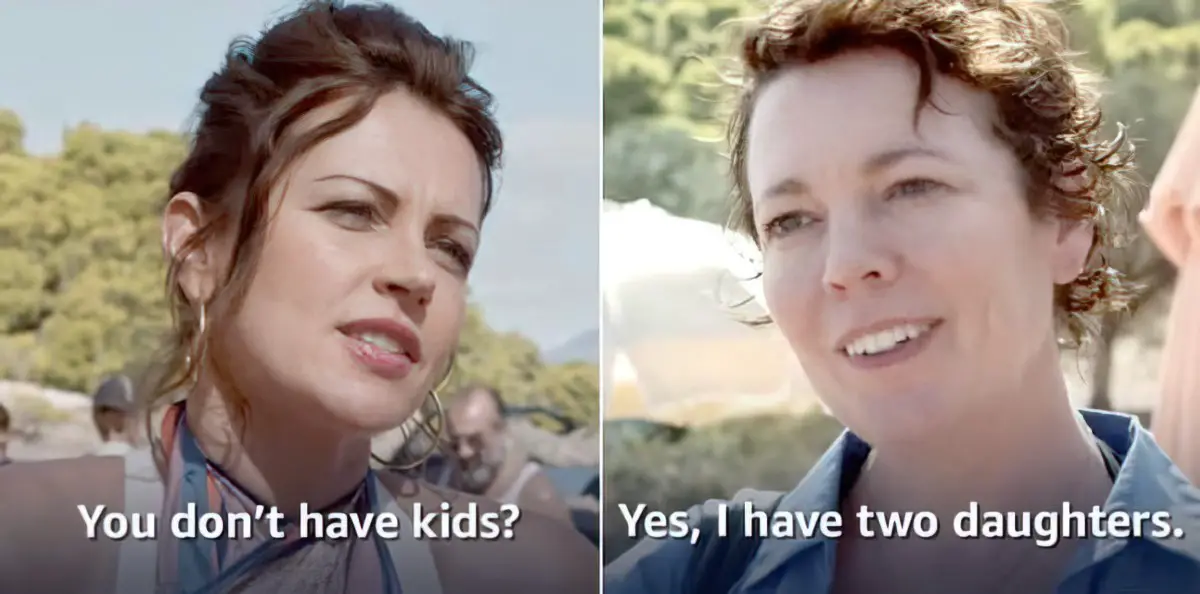

- The assumption from a stranger that you can’t be a mother because you don’t have your children with you at that particular moment.

- The way a mother turns by instinct even when someone else’s child (in another country, in another language) rushes past you calling for their ‘mama’.

- The things people say — husbands, lovers, strangers — which shape mothers’ self-perception of their own parenting ability.

- The invisibility of the middle-aged woman, past her childbearing years, and past her usefulness in the eyes of men. Her complete lack of power to do anything about a rude group of teenage boys in a movie theatre. These boys only listen when a man of equivalent age steps in.

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

WHO IS ‘THE (REAL) LOST DAUGHTER’ OF THE TITLE?

tl;dr: The lost daughter is Leda herself.

Below, my reasons.

MOTHERING AS VERB

Consider the English words ‘mother’ and ‘father’. The nouns form a neutral pair — gender differentiated parents, that’s all. But once you turn this pair of words into transitive verbs, it becomes clear how the culture which made the words sees mothers and fathers as roles with completely different responsibility loadings:

- to mother (someone): to nurture

- to father (someone): to provide semen for

Traditionally femme coded jobs (‘vocations’) are especially prone to romanticisation. Teaching carries the same high expectations: You must love your kids and love your job. This is a dangerous idea. Can’t teaching (and parenting) sometimes be just a job? If we acknowledged care work as real work (appropriating a sex work phrase), women might be less critical of themselves, on days when these very difficult jobs aren’t going well, and they often don’t.

INTERTEXTUAL INTERPRETATIONS OF THE LOST DAUGHTER

Those who’ve read Elena Ferrante’s book say the film and book are quite different, so I’ll be treating the film as a work in its own right. And by the way, Maggie Gyllenhaal had Elena Ferrante’s blessing to do her own thing with her book. Ferrante wrote a newspaper column as permission: “It’s her story to tell now.”

It’s important for me – for her, for all women – that her work be hers and turn out well. Mine already exists, with its strengths and defects. In the great warehouse of the arts, set up mainly by men, women have for a relatively short time been seeking the means and opportunities to give a form of their own to what they have learned from life.

Elena Ferrante, doing feminism.

Those familiar with Greek mythology, specifically the story of “Leda and the Swan”, will bring an extra dimension of intertextual experience to Gyllenhaal-Ferrante’s story. The main character is a literature professor named Leda. But like the young man in the film, I’m not familiar with Leda and the Swan outside what I just read on Wikipedia. (That said, Leda the character talks a few times about her name within the world of the story, so you’ll pick up the basics.)

Insofar as it’s possible (it’s not), my interpretation of The Lost Daughter (the movie) is that of a standalone work.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE LOST DAUGHTER

A 48-year-old college professor of comparative literature, originally from Leeds, England, now working across the Atlantic in the Cambridge near Boston, America, arrives alone to a Greek island where she will rent a small house and enjoy a holiday alone, to read and think and relax. Her name is Leda Caruso.

The men who run her accommodations (one much older, one much younger) are both very welcoming. They seem to enjoy hosting a woman on her own. The young man reminds her there are ice-creams as she relaxes alone on the beach. Next we see Leda eating an ice-cream at sundown, suggesting she’s been eating ice-creams all afternoon, haha.

But now a large group of gregarious teenagers arrive to disrupt Leda’s peace.

The teenage boys are interested in a young mother whose bikini-ed body sets her apart as the object of interest here. Leda, too, is interested in her. Perhaps some viewers will pick up a homoerotic vibe, but it will later become clear that Leda is interested in her role as a young mother.

On her way back to her room one evening, Leda accepts a call from someone clearly close to her. The person on the other end is wanting hair advice, as she’s done something to mess up her hair. Leda mentions she’s on holiday and right now is looking out onto a– the person on the other end hangs up and we can deduce she’s been talking to a young adult child with an interesting life of their own.

When Leda catches sight of the beautiful young mother’s little girl playing with her doll beside her sunbathing mother, Leda wells up with tears and must retreat from the beach. She asks the young man who works there, Matt, for a glass of water.

Next arrives the rest of this large, Greek family, the New York side. The pregnant 42-year-old matriarch of this crowd expects Leda to move down the beach so her family can properly spread out. It’s her birthday party, you see. More than an ‘opponent’ in the traditional sense (a character who stands in the way of whatever the main character wants), this woman is more of a ‘reflection character’ (a character designed by the storyteller to exemplify another sort of person with an alternative worldview).

Leda refuses to move down the beach as brusquely requested. The birthday woman, called Callie, clearly feels entitled to the entire space. Incensed, Callie glares. This scene exemplifies the realism of The Lost Daughter, where glares are far more common than fisticuffs and retribution… though the retribution may be coming. For storytelling purposes, Leda’s proximity to this birthday party and to these people is useful because the story plays out through Leda’s eyes, and now we have a wider cast of interesting characters.

Later, Callie regrets her rudeness and offers the nearby Leda, all alone, a piece of her birthday cake. She ‘offers’ the cake in the way she ‘offered’ Leda the chance to move down the beach. She’s not taking no for an answer until Leda eats at least a few bites. While this happens, Callie quizzes Leda for her backstory (by this time the audience is after some, too) and we learn about Leda’s two grown daughters.

As you watch this film, look out for the various types of reflections which lurk inside the symbol web.

For example, on her way along the dirt track, which leads from the beach to her accommodation, Leda is hit on the shoulder by a large pine cone, leaving a large, visible bruise. This is the ‘fall’ which contributes to her later recollection of the doll which fell out of the window and smashed. (She threw it in a rage after her daughter drew on it with pen.)

Leda — or the audience — may interpret the bruise of the inanimate pinecone as divine retribution for defenestrating her doll in a violent-adjacent act, which in turn may bring to mind the other famous Fall — the one kicked off by Eve in the Garden of Eden: the fault of the woman, even though Eve wasn’t even told by the serpent not to eat the apple, and Adam didn’t think to pass that tidbit of information on. (Didn’t I tell you it’s impossible to leave intertextuality at the door when attempting to understand a new story?)

An event such as a falling pinecone in the present time of the story initiates a thread of interweaving memories and thoughts. In what ways are women blamed for failing? Can mothers (women, the Eves, the Pandoras et al.) really be blamed for starting everything bad in the world, however indirectly, simply by dint of being mothers, and thereby responsible for everyone’s earliest, most formative moments?

Another symbolic reflection can be found in the hotel manager, the older man (Lyle) who, like Leda, carries the burden of parental regret. Lyle contrasts with Leda (note their names both start with the same letter — writers of lyrical works often do this). Lyle also contrasts with Matt, the young university student who works at the resort over summer. Like Alice Munro does frequently in her short stories, the older woman main character of this story co-exists with her younger self, reminded of her younger self by the co-existence of young and old characters who populate the present. Time seems less linear. Our older selves co-exist with our younger selves because the past informs the present. We can never escape that fact. This storytelling trick makes a story feel circular, round like a femme-coded (pregnant) circle.

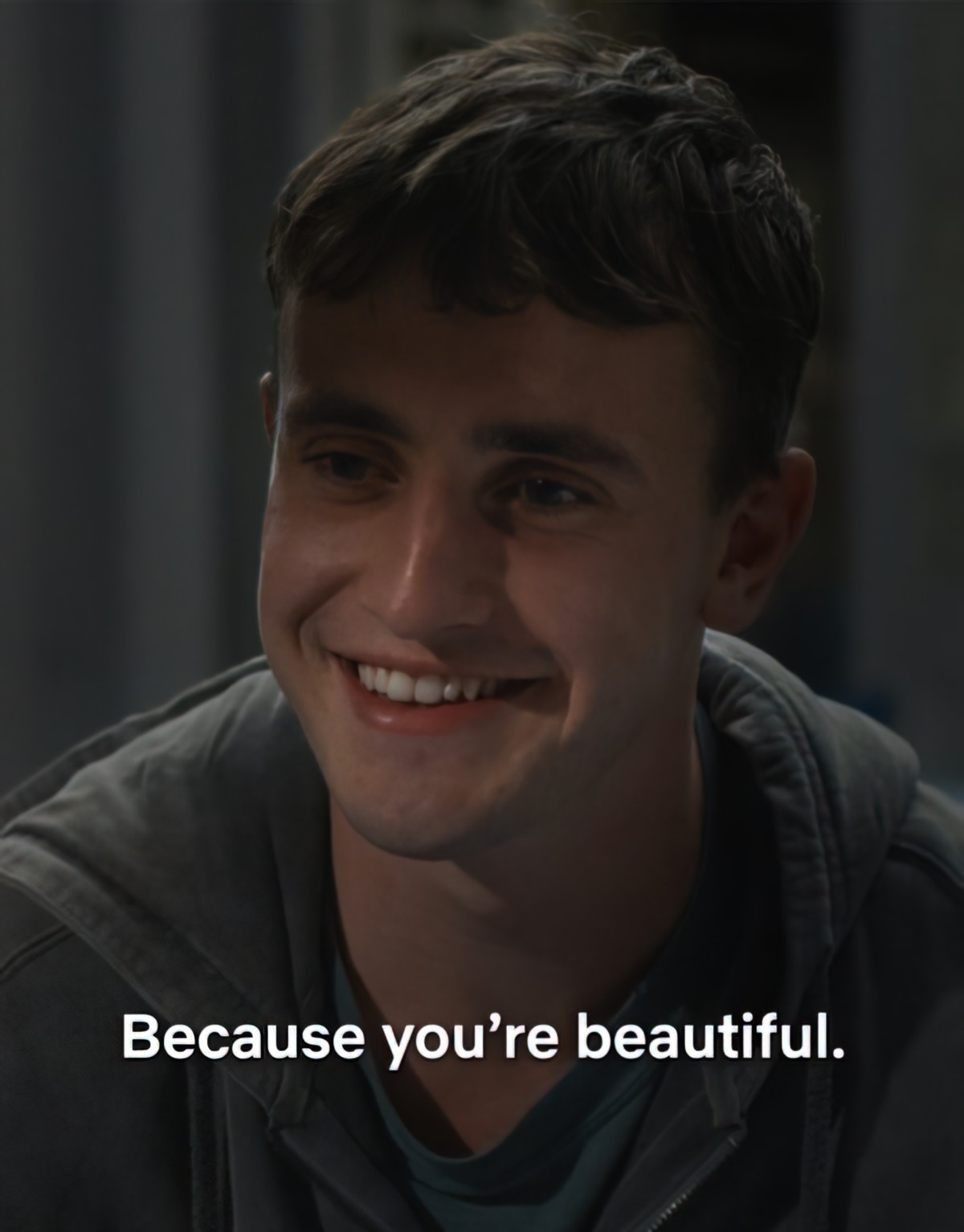

When she invites the younger man to dinner (and pays for him), he indulges in safe flirting. He’s giving Leda the gift of a revisit to her youth. Leda is too savvy to accept at face value the young man’s compliments regarding her beauty. But she appreciates his gift nonetheless.

Matt is played by the same actor who played Connell in Sally Rooney’s Normal People. I was surprised to hear him string more than three words together. His character juxtaposes against the age and experience of Lyle, who also expresses interest in Leda, but perhaps only because he sees in Leda a deep loneliness, one which he has experienced himself. Leda, alone at a bar, has earlier brushed him off quite rudely, “Do you mind if I finish my meal?” then, after finishing, makes an awkward attempt to flirt with him.

But she has lost the knack. She has misinterpreted his intentions. All her life, a seat at a bar and her existence as a woman gives out a certain signal: Now, as a woman nearing menopause, there’s no such signal. Now, a woman sitting alone at a bar attracts an offer of sex-free company. She fails to realise this. Haunted by the past, which lingers into the presents, Leda, unlike the rest of the world, cannot simply cast aside her younger, sexual (and sexually-objectified) self. It’s still there, even if people can’t see it.

Back to the very good looking member of the Greek family: Nina, mother of Elena, about four years old. When Elena goes missing, Leda joins the search party and it is Leda who finds the little girl, wearing her mother’s massive hat, digging in the sand behind trees. It is Leda who reunites the girl with her mother; Nina and Leda speak for the first time. “I love your swimming costume,” Nina says to Leda, meaning “I love you at this moment.” (The actors have explained the subtext of this line of dialogue.)

It is soon revealed to the audience that Leda has kept (or taken) the little girl’s precious doll. Earlier she told Nina that she had one just like it as a little girl.

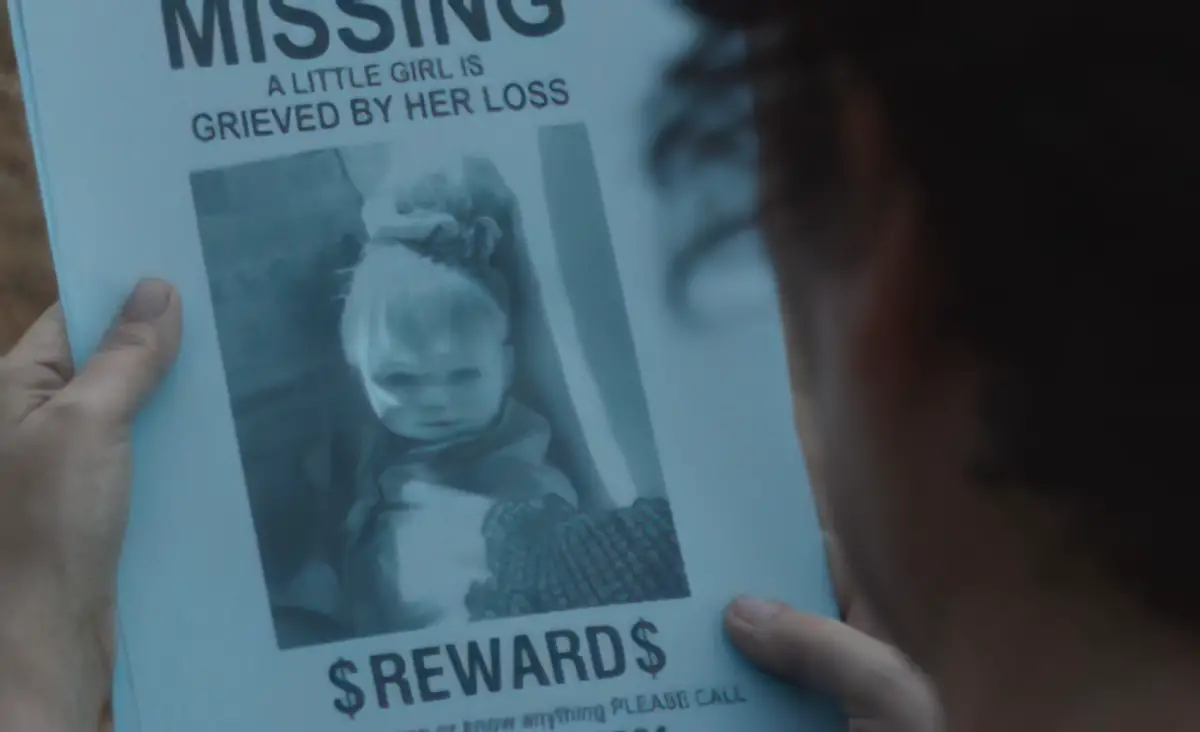

Turning the doll into a creepy plastic version of a real child, Nina and Callie plaster ‘missing doll’ posters all over the village. The little girl is distraught.

Meanwhile, in her own accommodation, Leda is nurturing the doll. It even ‘spits up’ on her shirt (mud). Leda goes to the nearby toy shop and is buying some doll-sized clothes for it when Nina and Callie happen to enter, with an unsettled and very annoying young Elena in tow. Callie and Leda have a fraught conversation about motherhood (Leda makes the point that Callie knows nothing about it yet, since she’s pregnant with her first child). Nina confides to Leda that she’s finding parenting difficult.

Lyle brings fresh-caught octopus to share with Leda. Leda still interprets this as a romantic gesture but Lyle isn’t comfortable with her using his shoulder as a pillow and gently suggests she lie down. He’s caught her by surprise, with the doll in full view on the deck. When Lyle goes out to the balcony for a smoke, he sees the doll but only comments that it’s full of water.

On a walk, Leda happens to catch sight of Nina kissing Matt in a private spot near the beach. Matt has already told Leda about this family, how they’re “not good people”, and how dangerous they are if they don’t get what they want. Next time they make a request of her, he advises, do as they ask. Yet here Matt is, cuckolding Nina’s volatile husband, who we have seen in action on the beach. He’s handsy and possessive and shouty.

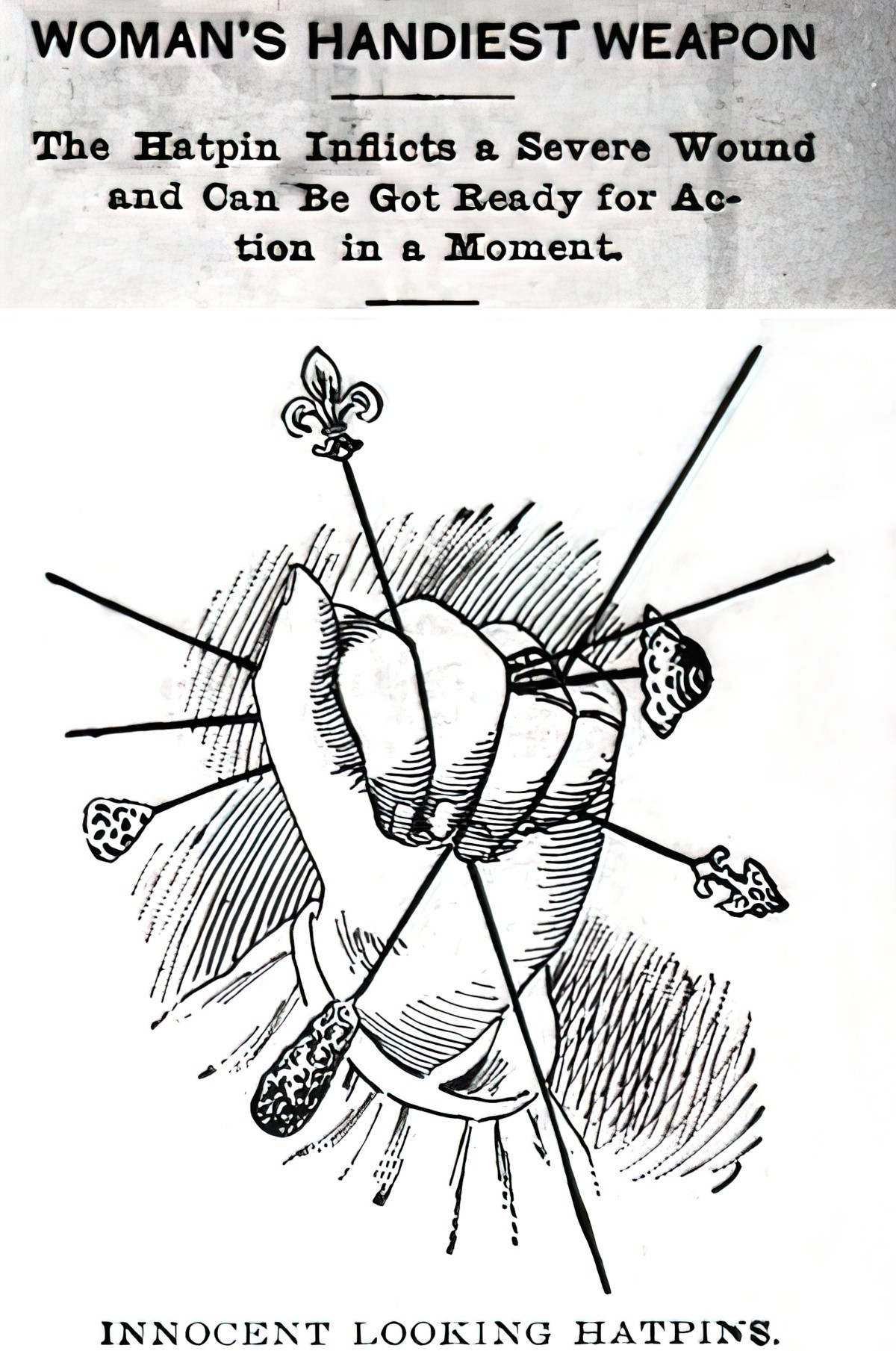

Nina and Leda encounter each other again at the street market, where Leda buys a hat pin for Nina so that her massive hat can’t fly away in the wind.

Nina knows that Leda saw her with Matt, and asks her the favour of keeping it quiet. She also shares with Leda that she knows Leda is a good person, and not the judgmental type. Leda agrees that she’s in no place to judge, and will keep that information to herself.

The audience might be wondering at this point: Does Nina know Lena took the doll? The little girl seems to. But no.

One evening Leda sees a movie alone, when the theatre is invaded by the hoarde of teenage boys who keep invading her space. She asks them to be quiet, they get worse. She asks the younger woman who works at the theatre to sort out the situation, but the boys are playing a game with her, too. It is only when an older man known to the boys enters the theatre that the boys calm down, but they have spoiled Leda’s evening. Why? What is this really about? Not just the movie, and the anger of intrusion and rudeness. It’s the utter lack of human respect afforded to an increasingly invisible middle-aged woman. As far as the young men are concerned, she doesn’t exist. There’s a freedom in this, but there’s also a downside.

Leda becomes more and more paranoid, and even imagines(?) she hears someone knock on her door in the middle of the night. The strobes of the lighthouse seem to be looking right into her soul, judging her.

All of this stuff happening on the Greek island has framed the backstory of Leda, which is basically this: She gave birth to two daughters very young, in her early twenties, and didn’t enjoy motherhood. We see her unable to kiss her daughter’s finger, we see her cast a doll out of a window, and break the glass of an internal door (accidentally) while in a frothy, but mundane, rage. We also see her being a perfectly good mother.

But the standards of ‘good mother’ are so high, some mothers internalise a heartbreaking shame and need to get away. To stay, for Leda, would be a type of death.

So when Leda is offered the opportunity to exercise the academic side of her mind, she takes it.

While away on a lecture tour of some sort, she has an affair with an older, beguiling professor, and takes the opportunity to leave again. She doesn’t see her daughters for three years. In the meantime, her male partner (husband?) and mother have taken good care of them. Although Leda resumed her role of mother upon return (we don’t know the details of that), she will always bear the guilt of that three years in which a mother abandoned her daughters.

Matt visits Leda at her accommodations one evening and asks to come up. Leda declines. What’s he here for? He’s come to ask a favour on behalf of Nina. The two of them would like to borrow her rooms for a few hours, for obvious reasons. Leda tells Matt to send Nina round herself. It’s unclear how Leda feels about this favour. Is she jealous about Matt, about their youth? Or is she regretful about her own extramarital relationship all those years ago? Is she feeling guilty for enabling this pair, or simply annoyed that they’re possibly putting her in danger by implication? We don’t know. Likely: Leda couldn’t tell us, either. She’s not someone attuned to her own emotions.

This becomes apparent when Nina does come to see her. Leda brusquely offers her the house keys, but Nina needs more of a connection with this older woman. Nina needs someone to know her, to really know her, or perhaps, selfishly, she simply needs a confidante.

At this point, annoyed, and not valuing the nascent friendship she’s striking up with this younger mother, Leda produces the precious doll. If Leda didn’t want to cause pain and put a full-stop on this short-lived friendship, she could simply accept Nina’s praise for finding the doll. But instead she confesses to taking it. She was… “playing”. Nina interprets “playing” as a vindictive act as in “playing with a little girl’s emotions”, whereas Leda meant it in the most literal way. She has been playing with the doll, as little kids play with dolls.

Nina switches modes from friendly, quiet and confessional to angry and threatening. As she leaves, she stabs Leda in the stomach with the hatpin Leda bought for her.

Leda pulls the hatpin out of her stomach, drives almost fainting to the sea, and collapses where sea meets the sand. This is where the story opened.

Waves wake her up the next morning, lapping at her face. She returns a call to one of her daughters — both are at the other end, worried about her.

One reading is that the daughters have an emotional connection with their mother and sensed something was wrong.

Psychologically, Leda has returned to motherhood. We might deduce that, this time, she will have the strength to offer her grown-up daughters more of herself.

But Leda has not benefited from any new insight about herself. It’s just as likely she won’t change. She won’t feel any less mother-guilt. This holiday has afforded her space, and time, and for Leda, space and time to think has proven dangerous. She does strange things. We can deduce that she’ll return to her busy life as a professor and function as a busy and normal person.

Does Leda as a character feel authentic in this regard, as a literature professor who can interpret a fictional character in great depth, but who does not turn the gaze upon herself? At first I thought this messes with the realism, but then I thought of Leonardo Da Vinci, renowned polymath, influential artist and autodidact. From his mid-thirties, Da Vinci kept copious notes. We know from those notes that despite his deep curiosity about many things, he did not show the same curiosity for himself. He did not introspect. Some people are just like that, geniuses included.

WHY DID LEDA STEAL THE DOLL?

When asking this specific question of a story, we may be asking one of two things:

- Why did the character Leda steal a little girl’s doll?

- Why did the storyteller decide to make Leda steal a little girl’s doll?

In fandom, the first question is after a Watsonian answer; the second a Doylist answer. (The terms come from Sherlock Holmes, in which Dr Watson is the fictional character in a work deliberately plotted and crafted out of nothing by Arthur Conan Doyle.) Other terms making the same distinction: in-universe and real-world perspective.

I’m interested in the real-world, Doylist take on this story: Why did the writer create such an unlikeable character as Leda? Wouldn’t the story have been more pleasant if Leda hadn’t stolen that thing? What’s the story purpose?

Of course it’s easier to write a story about a likeable character. Writers use many tricks to create such characters, and once you know what those are, they stand out like a sore thumb. Save the Cat, I’m looking at you.

Writers use these same tricks on steroids to create anti-heroes such as Walter White or Tony Soprano.

Then you get characters like Leda, who tend to attract a narrower audience, because people will say things like, “Gah, I couldn’t stand any of the characters, especially the main character. Why the hell did she have to steal that doll!”

At this point, I request of everyone a self-check, because the standards for “likeable” female characters are higher in fiction as they are in real life. If you “liked” Walter White but hated Skyler, or “liked” Tony Soprano” but hated Carmela, I’m talking to you.

We expect great things of mothers. Impossible things. The internal reality of being a mother does not map perfectly onto the external romanticisation of this role imposed by society. That’s the whole point. Of course Leda isn’t “likeable”. She exemplifies the part of a mother which longs to recover her own body, her own sense of self. The storytellers present audiences with the challenge, the spectacle, of a non-motherly mother. Most people find a non-motherly mother terrifying. Hence the terror of a fairytale such as “Hansel and Gretel“, in which ‘mother’ becomes bowdlerised to ‘step-mother’ precisely because the prospect of an unmotherly actual blood mother is beyond comprehension. That, of all terrors, will give the kiddos actual nightmares.

THE DOLL AS PORTAL TO LEDA’S EARLY MOTHERHOOD

The character of Leda longs to enjoy the years of early motherhood she never enjoyed as they were happening in real time.

The doll provides a link to the framing story of Leda’s early motherhood in which she gifts a doll to her daughter. This doesn’t go well, in which case the doll is a metonym for how mothering went for Leda more generally (not well).

THE DOLL AS PORTAL TO LEDA’S OWN EARLY CHILDHOOD

The doll Leda gave to her daughter was a doll from her own childhood, which connects Leda to her daughter, and also connects Leda to her young self.

There’s nothing like parenting to take you back to your own early years. In this way, ‘The Lost Daughter’ of the title is Leda herself, as well as the daughter briefly lost on the beach, as well as the daughters she has lost due to them growing up and leaving her behind.

As evidence I offer you the setting of the seaside. Since ancient times, the sea has been symbolically linked to the womb.

The theory of evolution only bolstered this connection, as it is now widely accepted that our ancestors emerged from the sea. The film opens with Leda collapsing on the beach. This body of water bookends the framing story of Leda on holiday.

The movie begins and ends with Leda passing out right in that liminal space where sea meets the earth, where people are neither here nor there, stuck, and vulnerable to magical powers (or revelations).

In order for Leda to become the sort of mother who is acceptable to herself, she has had to regress to her baby-self, nurturing herself before she could possibly nurture her own offspring. Parents who haven’t been nurtured cannot nurture others.

Though Leda’s childhood backstory is apparently more fleshed out in the book, the film audience gets only a glimpse of how Leda’s childhood may have been traumatic: When the father of Leda’s daughters “threatens” to take them back to Leda’s mother so she can help share their care, Leda calls her family home a ‘shit hole’. (We learn this is exactly what he does.) How can a father possibly be expected to look after two little girls on his own? he pleads, literally on his knees.

Fair point? Yet we expect this of mothers all the time. Society is set up in such a way that we expect mothers to work outside the home as well as doing the full-time work of mothering. Fathers are not expected to do both, at least not to the same extent. But when a mother abandons her own children, expecting a single father to do what hundreds of thousands of single mothers do every day, he literally crumples, shrinking to the size of a child. When asked to do the nurturing work ascribed to mothers (‘mothering’), this father, who left the bulk of the parenting work to Leda, suddenly understands what an impossible task mothering is. He has collapsed into his own helpless babyhood.

This pleading obviously won’t work on Leda, who is leaving, because this is precisely the childlike helplessness she can’t be dealing with in her own actual children.

In one flashback, the well-known academic Leda has fallen for (played beautifully by typecast sleaze Peter Sarsgaard, also Maggie Gyllenhaal’s real life husband) chides her (literally smacks her) for expressing honesty about not wanting to talk to her own children on the phone.

The Most Selfless Thing I’ve Done Was Admitting I Hate My Children

The Atlantic Pitchbot on Twitter

“Don’t say that,” he warns as he sits paternally on the side of the bed. He admires Leda’s mind, and has made a name for himself for speaking the unspeakable, shocking conservative academics, yet even a man like this, who considers himself so renegade, cannot bear to hear the truth of mothering when it comes from a mother.

“What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?

Famous question asked by feminist poet Muriel Rukeyser in her 1960s tribute poem to the German artist and sculptor, Kathe Kollwitz

The world would split open.”

Everyone likes the fantasy that their mothers loved every minute of their childhood development. People who have never been a full-time parent themselves (mostly men) are particularly motivated to hold onto this fantasy. Oh, we’d all like this fantasy, it’s just that mothering shatters the illusion that you’d be the perfect, loving parent… if only you had the chance to be a parent yourself.

It is only by regressing to her babylike self herself that Leda, while on holiday, lying on that shore with the waves lapping at her face, is able to accept her own version of mothering. On the page, she suffers from an unnamed disorder wherein she’s prone to fainting if she stands up too quickly. Symbolically, this disorder allows the storyteller to place her back inside the symbolic womb. This mother, too, is a human with her own needs, and she did the best that she could with the resources she had at the time.

We know she’s experienced a measure of self-acceptance when she finally returns her daughter’s calls. The daughters thought she was dead. In storytelling terms, that’s exactly what happened. Characters, across all stories, must come close to (symbolic) death before experiencing anagnorisis.

DOLL AS SYMBOL OF THE UNNATURAL

The doll is made of plastic, which Leda at one point stuffs into the kitchen tidy. The toy was already ‘spewing’ up mud, and when she retrieves it from the kitchen rubbish, a grotesque, wormy insect emerges from its permanently open mouth. This doll is now your classic horror trope.

Horror loves dolls because fake babies live in uncanny valley. To emphasise the uncanny aspect of this doll, the camera zooms in on Leda pressing its head in, trying to get the goop out. Its face morphs grotesquely. This plastic object can never pass for anything like ‘natural’. Therefore, in this particular story, the doll is not simply a horror prop. It extends the theme of ‘unnaturalness’. The doll is not a real baby as Leda fails to think of herself as a real mother. By cradling it, hugging it, sleeping alongside it, Leda attempts to bring this unnatural baby to life. She is really trying to coax her ‘unnatural’ self to life, not that she ever realises this about herself.

Leda never achieves the psychological insight. “Why would you steal the doll?” she is asked. When she says, “I don’t know. I was playing.” Book smart though she is, I believe the character when she says she doesn’t know. This is one of those stories in which the anagnorisis is experienced by the audience, not by the character. These stories require a bit more work. There’s no pithy speech, summing everything up for us at the end.

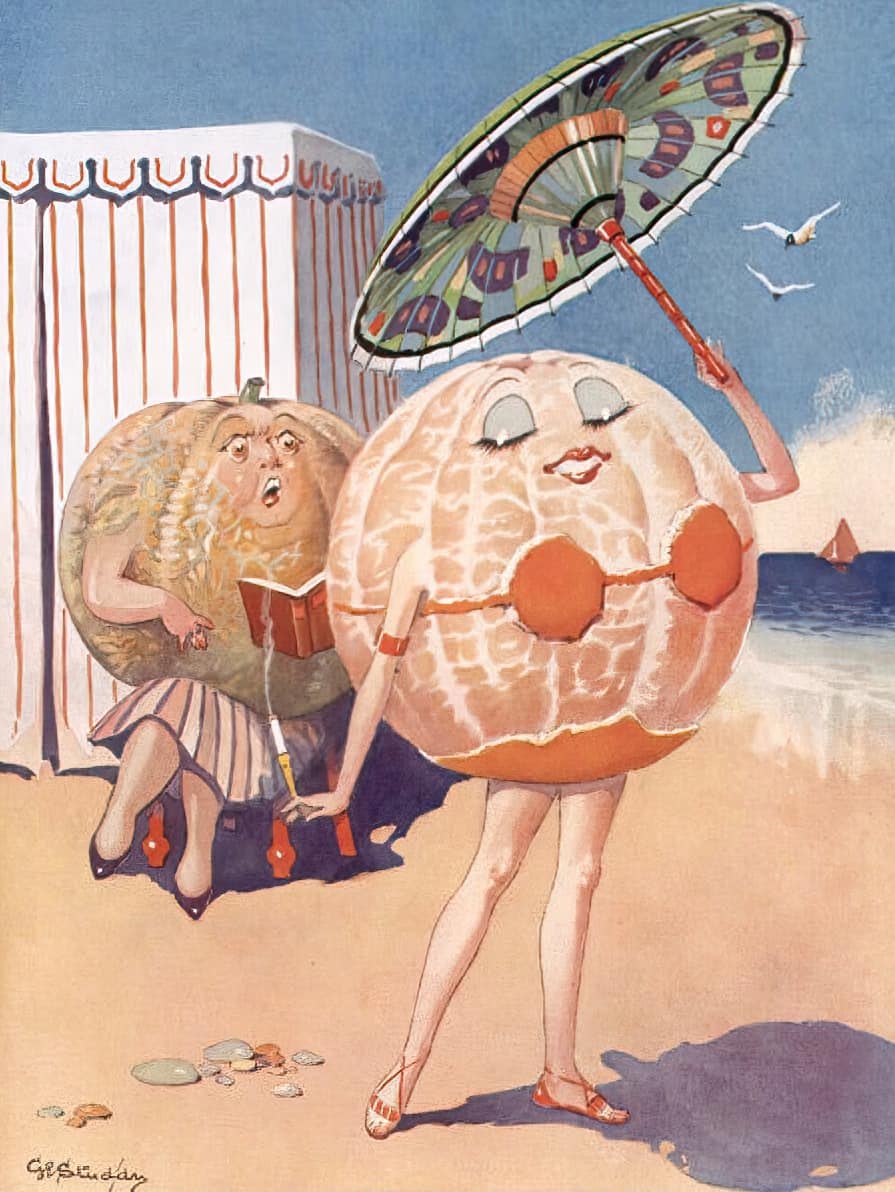

DOLL SYMBOLISM BOLSTERED BY THE MOTIF OF THE NAVAL ORANGE

Speaking of pithy, what’s with all those oranges? Rotten oranges, peeled oranges…

The Lost Daughter utilises fruit, specifically the orange, as a motif, meaning the orange functions symbolically, but in a way that is specific to the telling of this particular story.

When Leda discovers the complimentary fruit in her accommodations is rotting from the bottom and needs to be thrown out, it’s unlikely the viewer will think much of that. But after a while, after numerous scenes featuring fruit, we’ll likely wonder, “What’s going on here?”

At a plot-development level, the fruit of Leda’s holiday reminds Leda of how she used to peel oranges for her daughters, aiming to cut off the skin in one long strip. (I’m sure this is a motif within a motif — the linearity of grand-mothering which becomes mothering.) This links the framing story set at the beach to Leda’s years of young mothering.

Attempting to cut a long strip of orange strip unsupervised, one of Leda’s young daughters cuts herself with the knife, which creates an unpleasant mothering memory in which Leda cannot find it in herself to kiss her daughter’s finger better. She is totally, utterly emotionally spent.

The final memory Leda recalls, before leaving her young daughters for three years to work as an academic across the Atlantic in America, is of peeling them an orange for them then walking out the door. “Where are you going, Mummy?” the daughters ask as the door closes on them. This may or may not have really happened within the world of the earlier story. The scene could be symbolic: a neatly fabricated package of guilt.

Gyllenhaal herself offers an alternative reading of this film (“but not really”) in which Leda imagines this entire movie while passed out on the beach. She and the editor inserted a ‘subliminal’ image of Leda passed out on the beach in the midst of the frenetic search for Nina’s daughter, in which Leda, in parallel, recalls losing her own daughter on a beach, many years ago.

Back to the fruit. The symbolism of that orange becomes fully apparent in the final scene. Leda has just been stabbed in the naval with a hat pin she purchased herself as a motherly sort of gift for another woman. (The irony of this exemplifies how mothering can feel — giving everything of yourself, receiving back a stab in the ‘womb’.)

“What’s a naval?” Leda’s young daughter asks as Leda sits up from her liminal bed on the beach. Leda explains that a naval is a belly button, and I hadn’t picked up until she said this: Those oranges are naval oranges.

Why are naval oranges called naval oranges?

The navel orange actually grows a second “twin” fruit opposite its stem. The second fruit remains underdeveloped, but from the outside, it resembles a human navel—hence the name. Navels are part of the winter citrus family. They’re seedless, peel easily, and are thought to be one of the world’s best-tasting oranges.

The Fruit Guys

A tiny second self inside the mother fruit? Well, doesn’t that just tie together neatly with that parallel symbol web of the doll, and how Leda needs to mother her own self before she can be a mother to other adult women, two of whom are her own, grown-up offspring.

Maggie Gyllenhaal did not choose a Greek island as filming location for storytelling reasons. During covid, many other considerations came into play. (Ferrante’s book is set in Southern Italy.) But by complete coincidence, we might draw another parallel between the Greek island and the navel: A well-known island from Greek mythology is Ogygia, considered ‘navel of the sea’. A happy storytelling coincidence, and proof positive that not every connection made by an audience was intended by the storyteller.

THE LOST DAUGHTER AS “PSYCHOLOGICAL HEIST”

Gena Radcliffe at The Spool queries whether this film should really be marketed as a (psychological) ‘thriller’, but acknowledges that the story makes use of some classic thriller tropes e.g. the freaky lighthouse:

There’s a fascinating sense of unease to everything that perhaps earns it its “thriller” description. A lighthouse casts a constant beam through Leda’s apartment, as if watching her. Callie seems to look right through Leda with an almost knowing smirk on her face, asking prying questions and positing herself as some sort of expert on what a “good” mother is, even though she’s only pregnant with her first child. Even the overly friendly Lyle grins at Leda like he knows something she doesn’t. It is, of course, Leda’s own paranoia causing this, as if her status as an “unnatural mother” is written on her forehead for everyone to see.

The Spool

Unfortunately this term has already been taken, to describe psychological thrillers with heist sequences in them (e.g. Trance, directed by Danny Boyle) but I’m trying to describe something different here, something which describes the slightly unusual plot delivery of The Lost Daughter.

In a heist plot (a subgenre of crime), criminal characters carry out a crime with the audience in audience-inferior position, meaning we watch the crime unfold without knowing what they planned. Heist is a genre in its own right, but also describes an ‘unfolding of plot’ which you see in many stories. Breaking Bad and Animal Kingdom make much use of heist sequences. The first part of each season starts with all sorts of problems and issues, as the characters try to problem-solve, but as the season finale draws near, the audience doesn’t get to see exactly what they’re planned; we enjoy seeing them carry out their plans. The heist sequence is therefore an enjoyable reveal.

Can a quiet story such as The Lost Daughter be considered a heist story? Well, I think so. It does contain a crime at its core, though Leda hasn’t stolen a million dollar painting or broken into a jewellery store. She’s stolen a little girl’s doll.

And very deliberately, the storytellers are not showing the audience why she’d do such a thing. Not right away.

I’m calling The Lost Daughter a ‘psychological heist’ because regular crime genre heists work like this: The storyteller withholds the part where the main character makes plans to carry out their crime.

In this case, however, the storyteller withholds a different part of the basic story structure: the psychological shortcoming which prompts Leda to steal such a thing from a little girl. If this were a regular (albeit low stakes) heist plot, the audience would:

- understand that Leda wants the doll.

- We’d see her planning to steal the doll.

- We’d enjoy the suspense as she sneaks into the little girl’s bedroom (or whatever)

- and for sure she’d almost get caught as the mother comes into the dark bedroom to check the noise Leda created as she pushed the rusty window up in its casing…

But that sort of heist would be ridiculous. In this work of realism, Leda’s theft of the little girl’s doll can only ever be opportunistic, because despite being a professor of literature, this main character doesn’t understand herself. She hasn’t turned her analytic lens inwards, focusing instead on characterisation in classic works of literature.

So, typical heist plots reveal how their main characters carry out complex crimes, almost getting caught, narrowly escaping. In this ‘psychological heist’, however, the storyteller offers the audience a different sort of revelation: The gradual unfolding of life history which leads to a middle-aged woman stealing a little girl’s doll while on holiday alone at the age of 48. How does the unfolding play out? The beach holiday becomes the framing story, with flashbacks to Leda’s years of young motherhood. Another long essay would be necessary to describe the camerawork of this film, but I only encourage you to take notice of when the camera zooms in close, and how characters are introduced in extreme close-up first (and keeps returning to most intimate of shots).

Normally in film, longshots become mid shots which become close ups. This film inverts that, reminding us that this is a psychological exploration. We see via these close up views how young Leda’s not coping with motherhood, how emotionally distant she is from her partner and daughters, losing herself, losing her self-control. This is a woman plagued by guilt.

In this interview, director Maggie Gyllenhall explains that she wanted to avoid objectification of Nina. She was careful to introduce Nina on screen as a character with her own needs (another word for psychological shortcomings) and desires. She’s also very cognizant of her use of noir/thriller shots. (Noir isn’t a genre, it’s a way of shooting a film.) Even noise can sound like it’s of a thriller genre. For instance, the tense beach scene in which Nina reunites with her young daughter was built entirely in ADR (in a studio, after the fact, with ‘automated dialogue replacement’).

We might say The Lost Daughter pulls off a heist on its audience. Some might say it steals something from us: a tied-up plot featuring familiar, comfortable archetypes, and a main character who learns something about herself. But this is a character who doesn’t learn much about herself, because those people exist, too. Leda never understands why she kidnaps that doll. There’s nothing neat and tidy about a lyrical Postmodern work such as this. These stories expect their audiences to contribute part of the story, based on the Postmodern ideology that there is no one true reading of anything anyway, so who is the storyteller to enforce a certain reading?

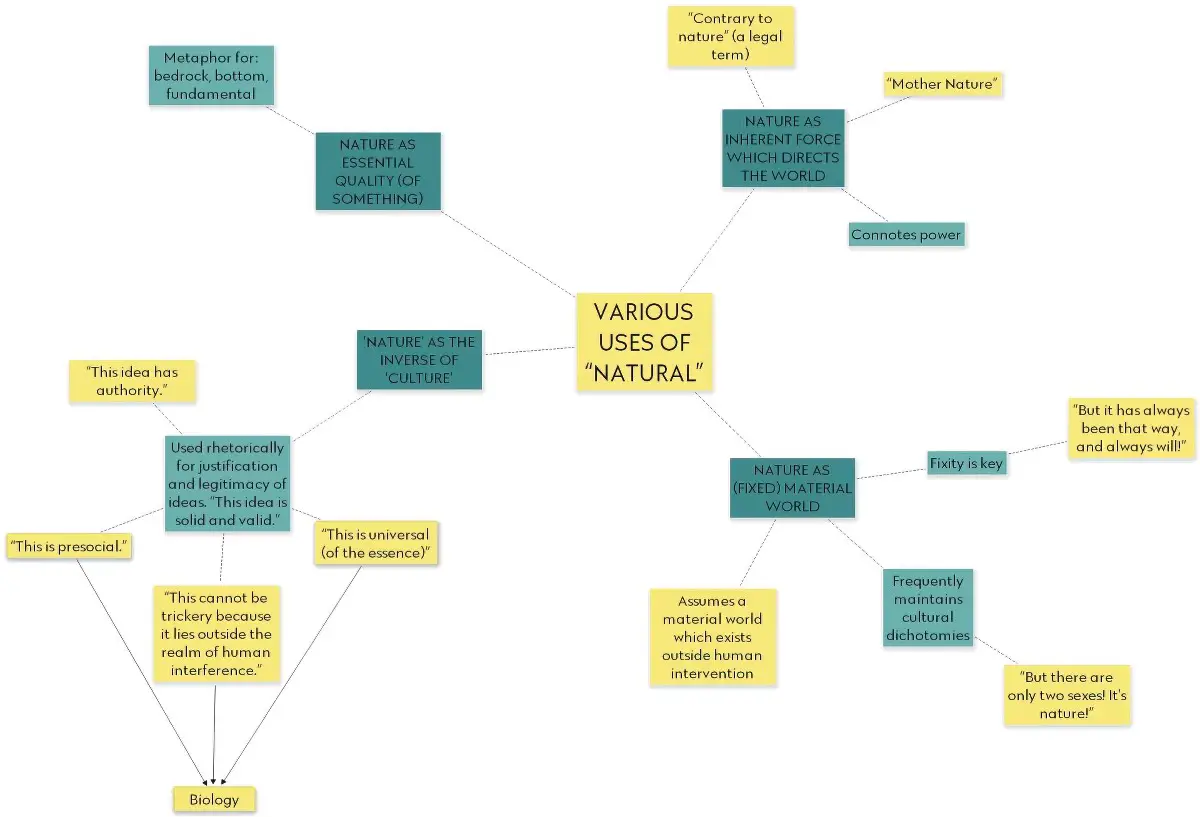

Likewise, there is no real-world binary of ‘good mother/bad mother’, however real the culturally imposed division. Mothers internalise this binarism, and apply it to themselves, because there’s a conceptual gap of ‘okay mother’. All mothers are either excellent or terrible. At one point, Leda says at her confessional unmasking: “I’m an unnatural mother.” This is binary thinking.

Instead of ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ mothers, The Lost Daughter interrogates the dominant culture’s ‘natural’, ‘unnatural’ dichotomy. Both fulfil the same social function (of tying womanhood to motherhood).

Note that the word ‘natural’ should always be approached with caution.

[Nature is] perhaps the most complex word in the language.

Raymond Williams, 1976, in Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society

Let’s talk about how the term “natural” is weaponized against women and trans people. 1) hormones/birth control: it’s “poison.” It shouldn’t be taken because it messes with our “natural” cycle and adds hormones into our bodies we don’t “need.”

2) pregnancy/childbirth: make sure it’s natural! Don’t take drugs! Women have been giving birth for centuries! They didn’t need any intervention or pain management! 3) breastfeeding: breast is best! It’s natural why do you need to feed your child anything else!

4) Pain management: oh a little period pain is normal! Just deal with it! 5) SSRIs: it’s just anxiety! Go for a walk and exercise!

6) makeup: why would you wear all that?! It’s so unnatural. I like you without makeup! 7) hair color: I only like NATURAL hair! None of those crazy colors like blue and pink and purple – I really like that blonde with the dark roots! NATURAL!

8) Any kind of cosmetic enhancements: I don’t want you to have any cosmetic surgery or fillers! You don’t need that! You’re beautiful just the way you are!

And to be clear: I’m not talking about your choices in doing what you want with your body. I’m talking about how many people (mostly cis men) weaponize the term “natural” against women and trans persons.

@_celia_bedelia_

Traditionally women have been identified with nature, a convention which has effectively precluded … the possibility of female protagonists interacting with nature in the way male protagonists have.

Jean Kennard, “Convention Coverage or How to Read Your Own Life.” New Literary History 13, 1 (1981).

LEDA’S PSYCHOLOGY

The days are long but the years are short.

Told to every young mother, everywhere, exemplifying the universality of sentiment among older mothers: I know this feels like drudgery now, but in hindsight you’ll long for this precious time.

Audiences must interpret for ourselves how Leda is feeling inside, and how her past affects her present. Especially at this point, interpretations will vary.

I see a mother who, only in hindsight, sees she had a small window of opportunity to establish a lifelong relationship with her daughters, now grown and emotionally distant. Instead, thick in the weeds of parenthood, she was unable to cope with motherhood let alone enjoy it. Now she’s in a much better space, she wishes she could do it all again. At the same time, she knows this is impossible, because if she were forced to do go back in time and do it all again, she wouldn’t cope next time, either. Instead she’s stuck in this loop: Only when free of the day-to-day drudgery of young motherhood is she free to romanticise it. The romanticises with extreme caution. She doesn’t want a mother-to-be to have unrealistic expectations of herself.

She steals the doll as a baby stand-in (this is hardly a mental leap) and she takes it now, while on her middle-aged holiday, because it is only when she’s truly alone that she is able to revisit the idealised landscape of motherhood romanticised by society.

Motherhood is romanticised — perhaps most obviously of all — by women who haven’t (yet) had children, acculturated by a society which rewards femininity, and controls fertility by making sure this prized version of femininity remains contingent upon a self-sacrificing form of motherhood.

LEDA’S REFLECTION CHARACTERS

CALLIE

In a time when audiences seem to demand that filmmakers carefully delineate which characters are “good” and which are “bad,” the characters in The Lost Daughter all exist in a far more realistic gray area. Callie could easily be set up as a one-note villain to Leda’s heroine, with Nina the innocent they fight over. But, as it turns out, Callie’s role in everything ends up being almost a red herring.

The Spool

Callie is the entitled, pregnant 42-year-old from New York, who first clashes badly with Leda, then apologises. These two women can never really be in psychological union because they represent two disparate categories of women: mothers and not (yet) mothers. Despite never having parented, the pregnant woman has firm opinions. “A mother never forgets things about her children,” she declares. “Based on your own experience, is it?” Leda replies.

Did this story need the characte rof Callie? Yes, because Callie’s storytelling function is to push Nina and Leda together because neither Nina or Leda like her very much. She also represents that in-between state of motherhood. There are non-mothers, mothers, and then there are pregnant women. All of these states of being are different experiences of the world.

YOUNG MOTHER NINA (CALLIE’S SISTER-IN-LAW)

Dakota Johnson (who plays Nina) says ‘you don’t really get to see two women so fascinated with each other’ in fiction, and points out that the two women have ‘a little obsession with each other’.

By my reckoning, this isn’t brand new territory. I can name other examples in which this dynamic plays out. In fact, I think it’s having a moment. TV series Killing Eve (2018-) explores this femme-coded, obsessive dynamic across several seasons (so far).

The lyrics to Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” (1974) seem regressive now, and speak to the weakest place in a woman. But they strike me as the meditation of a woman who is far more interested than this other woman than in… ‘her’ man.

Adrienne Rich* described the institution of ‘compulsory sexuality’ as a political structure that compels all women, straight and gay alike, to regulate their relations to other women in a way that is congenial to patriarchy. One of its mechanisms is the tacit instruction of women in how they should feel, or interpret their feelings, about women they admire. The appropriate response is envy, not desire. You must want to be like that woman; it could never be that you simply want her. But when it comes to the men they find compelling, the opposite applies: it must be that you want him, it can’t be that you want to be like him.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021) p138

The lyrics of “Candy” by Doja Cat come from a harsher, dirtier narrator, but I notice similarities to the older “Jolene”:

She’s just like candy, she’s so sweet

But you know that it ain’t real cherry, know that it ain’t real cherry

She’s just like candy, she’s so sweet

But you know that it ain’t real, know that it ain’t real can be your sugar when you’re fiendin’ for that sweet spot

Put me in your mouth, baby, and eat it ’til your teeth rot

I can be your cherry, apple, pecan, or your key lime

If people take any chapter from my book I hope it’s Envy because it’s the gateway to the other sins. What happens with women, and what we perceive in culture as ‘woman on woman hate’ or the way that we’re hard on each other, is typically undiagnosed envy. So when we see another woman and we have this rage towards her, annoyance, irritation, it’s this, “I don’t like her” or “Who does she think she is?” or “She rubs me the wrong way”. That woman is doing something or has something that you want for yourself. And she is pushing on a dream that you have for yourself.

Elise Loehnen Walked Away From Fame & Money For A Smaller (Better) Life, and is now author of On Our Best Behaviour

WOMEN WHO ‘DECIDE’ TO BECOME PARENTS

I mindfully avoid using phrases such as ‘women who decide to become mothers’, ‘mothers who decide to work’ and similar phrasing.

A gendered linguistic pattern has emerged in which the words ‘decide’ and ‘opt’ are used far more frequently when describing women than men, incorrectly suggesting that women are more in control of their own life choices than other genders.

Lynne Murphy also points out that deciding to do something does not mean actually doing it, and that ‘deciding’ to do something is the precursor to both succeeding AND failing at it.

Also, when we say a woman ‘decides’ to do something, rather than saying she ‘does’ something, the wording undercuts her achievement.

This example reminds me of the phrase ‘who identifies as X’, suggesting, for instance, that a trans woman who ‘identifies as a trans woman’ is not, in fact, a trans woman, let alone a woman of any kind.

*Because I have mentioned Adrienne Rich

what I’m trying to tell you is that there’s a very influential book that argues for the “mandating” trans people “out of existence” (verbatim) and that this book was edited by Adrienne Rich

what I am not telling you is that Adrienne Rich is a “complicated figure.” this is not some Gloria Steinem apologizing blandly in the 2010s type situation. what I am telling you is that Adrienne Rich edited a book that calls for the mandating of trans people out of existence

what I am telling you is that this book has had enormous consequences for trans people, particularly trans women, particularly in north america and the UK

I live in a poetry community where you mention her name to me and you don’t mention this

I live in a poetry community where you mention her name in public where you know I sometimes am and you do not mention this

and yes, you are right, she is a “complicated figure.” I also enjoy the poetry and have been influenced by the thought of Adrienne Rich

we would like to talk about Adrienne Rich. you are a feminist poet, or a feminist critic, and you have an investments in what is called “feminist thought.” but somehow, you are concerned only w rehabilitation. you have no interest in accounting for The Transsexual Empire.

this is not a part of your feminist project

so if I have ever seemed, at times, a little too angry, paranoid, or resentful, it is because you mentioned, in front of me, sometimes to me, many times, many times, a woman who had edited a book that says I should be mandated out of existence

and you did not mention that fact, and many times you did not know it, and when I told you you became upset, and I comforted you

so I live on another planet from you I guess, and I will not be meeting you, because how can I? how can I do what you’ve asked of me? if I did what you are asking of me, I’d go mad from a deficit of dignity

@supermattachine, Stephen Ira, who wrote a poem about this.