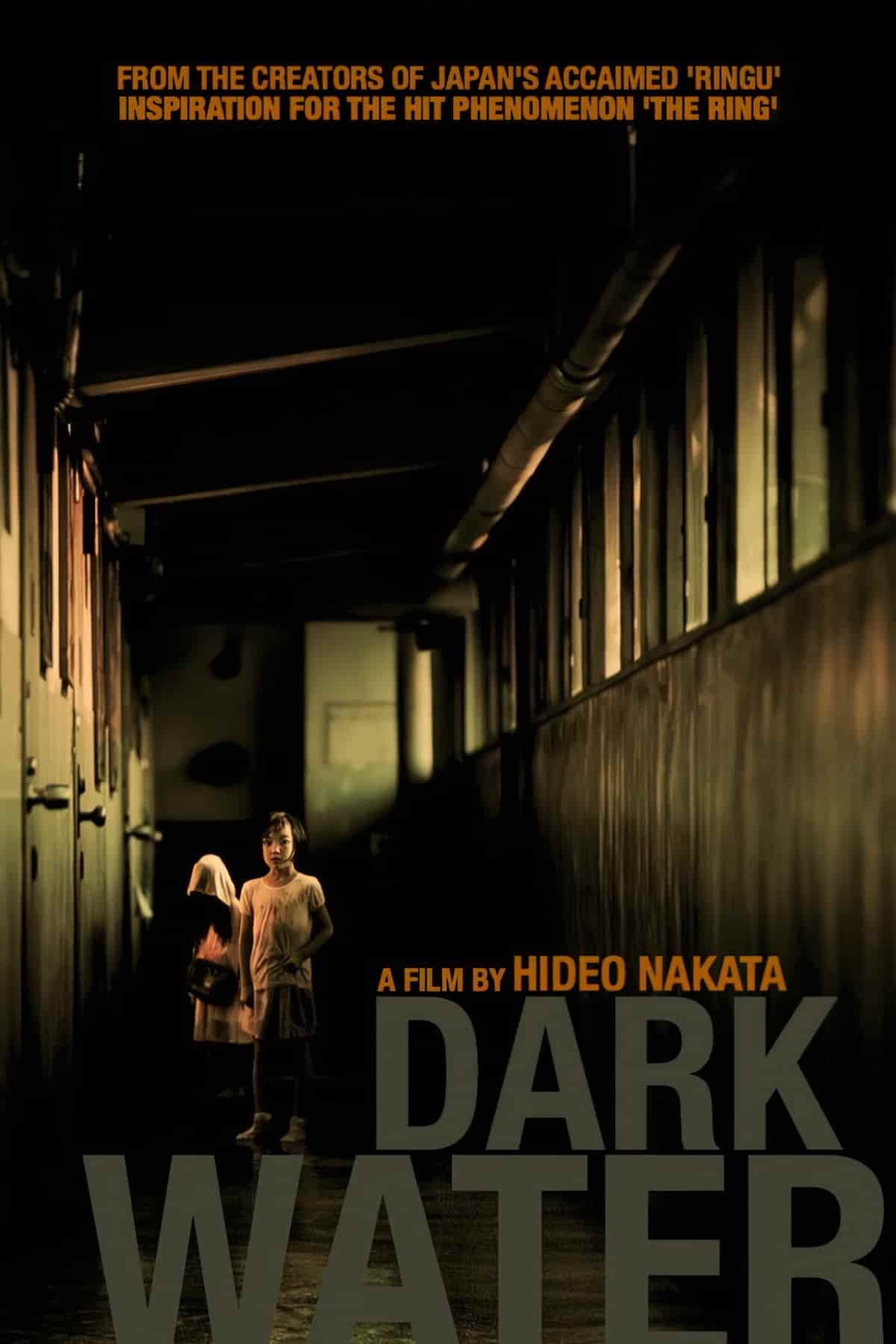

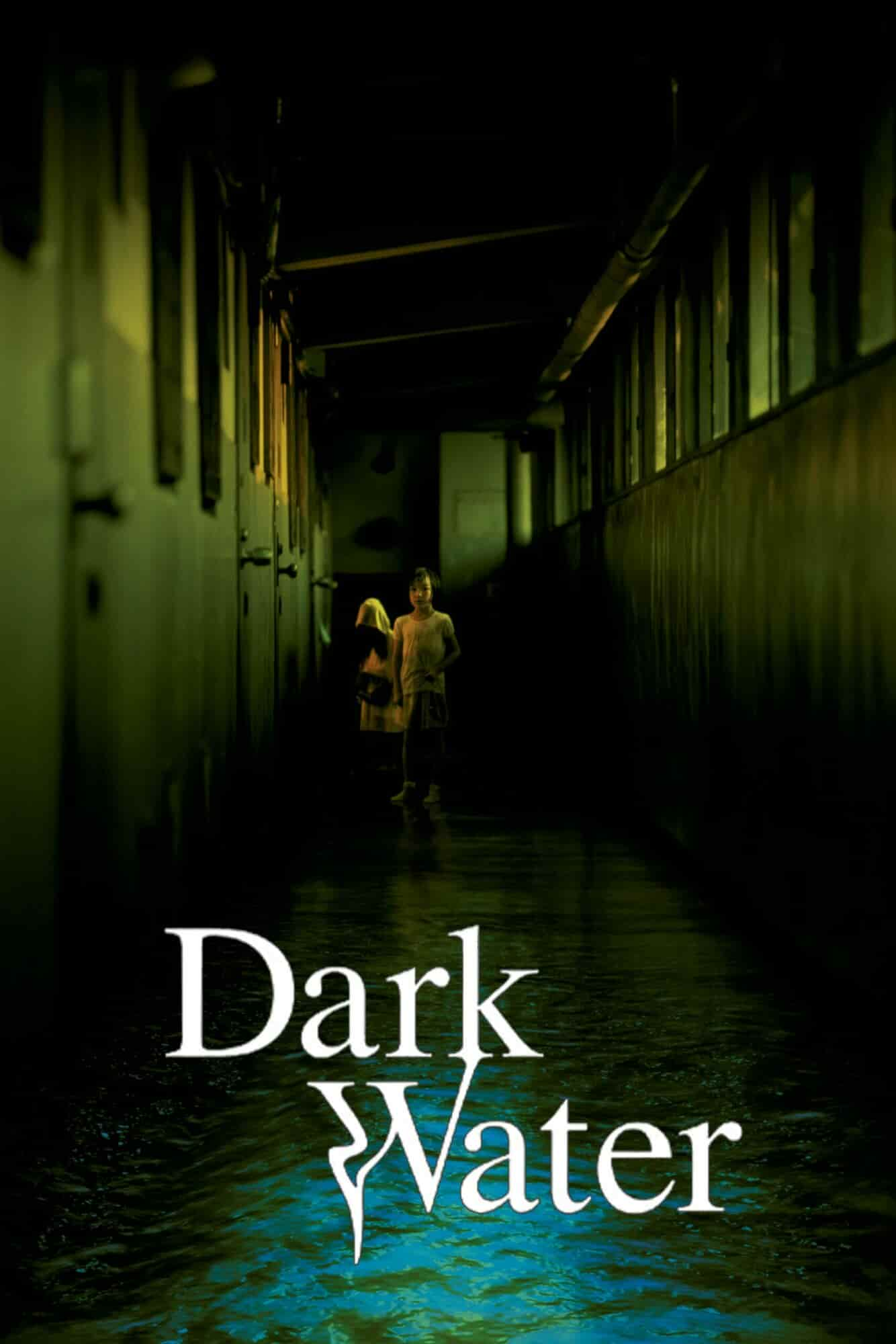

Today let’s talk about an excellent Japanese horror film (J-horror) directed by Hideo Nakata based on a short story by author Kōji Suzuki, who also wrote The Ring.

Content note for child drowning.

If you’re looking for a useless but cool gift for the lover of J-Horror in your life, a tiny ornament of a Japanese girl emerging from a refreshing cup of water might be the way to go?

THE STEPHEN KING OF JAPAN?

Kōji Suzuki is said to be the “Stephen King of Japan”, an uncomfortably racist take. Not everything originates with a white person.

over the last decade Mr. Suzuki has written a series of horror novels and short stories that have earned him the title — one that alternately annoys and flatters him — of the Stephen King of Japan. He has sold more than 10 million copies of his books in his native country. But much more so than Carrie or Cujo or Christine, Mr. Suzuki’s most frightening creation — Sadako, a demonic, hermaphroditic girl at the center of his 1989 book “The Ring” and its sequels — has pervaded Japanese popular culture, becoming a boogeyman used to scare children and, for adults, a metaphor for everything corrupt, cruel and frightening about modern society.

Bringing Out the Horror of What He Knows Best, a 2004 profile in the New York Times

When I lived in Japan, I noticed the extent to which Japanese artists are widely dismissed via analogy to some more broadly well-known Western creator. Perhaps we just need to even things up, and start calling Stephen King the “Kōji Suzuki of the USA”.

Like, if a Japanese pop musician produces a hit which sounds familiar to a Western audience, they’re said to be copying a Western artist. Accusations of mimicry don’t happen to the same extent with Western artists, who are also ‘copying’ each other because no artist is a standalone entity. Everyone draws from a connected creative well. Everyone has inherited the same cultural history and we are all riffing on that.

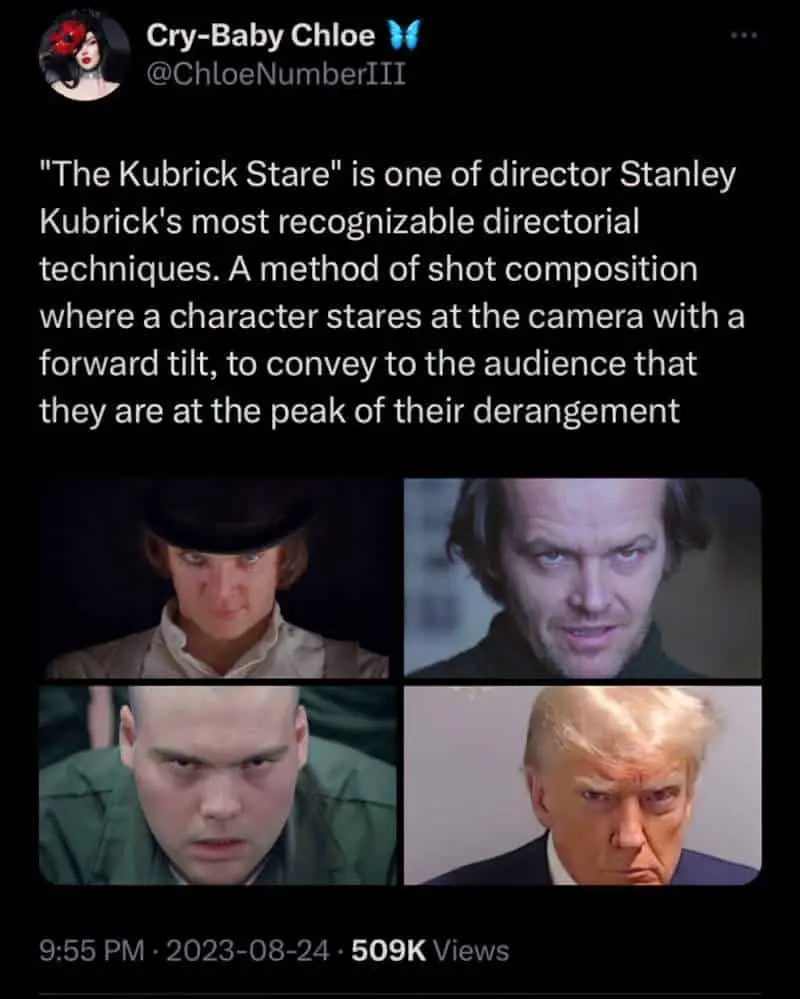

That said, similarities between Stephen King and Kōji Suzuki can absolutely be drawn. A famous scene in Stephen King’s The Shining depicts elevator doors opening to let loose a river of watery blood, filling the hotel corridor. In the West, more people have seen The Shining than have seen Dark Water.

But horror around water, especially bodies of water such as wells, is a Japanese horror trope from antiquity. Fear of water doesn’t belong to any specific culture.

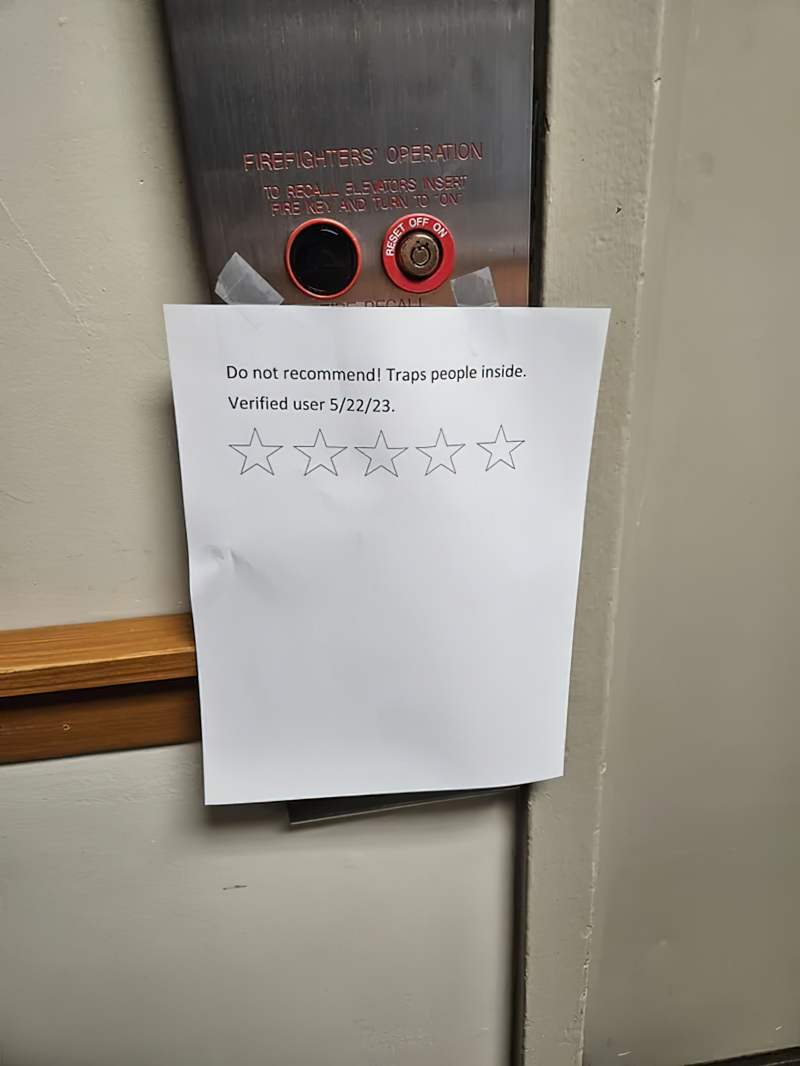

THE HORROR OF ELEVATORS

Elevators make a frequent appearance in contemporary Japanese horror. Elevators are inherently scary contraptions which tick all the everyday-horror boxes: They trap you inside, the doors seem to function like jaws, you’re beholden to technology (such as snappable pulleys, and electricity, which sometimes fails).

Even if technology goes well, you must share airspace standing uncomfortably close to complete strangers without seeming to look at them. These strangers could be serial killers for all you know. We’re told to avoid elevators in emergencies, adding to the horror. (When will there by an emergency? Anytime!)

Elevators function like portals, dispatching us to other worlds (floors), and always within large, labyrinthine buildings which in turn have their own horror associations. They are frequently lined with mirrors which create a mise en abyme effect. The muzak which often plays only seems to magnify the unpleasant whir of those unseen contraptions saving us from death.

EVERYTHING HORRIFIC CAN ALSO BE COMEDIC

Okay, so there’s a fine line between horror and comedy:

Do dogs understand elevators or are they just like ‘Ok it’s time to get into the world changer’?

@ronnui_ on Twitter

OUR ELEVATOR IS HAVING SOME ISSUES by ALEX BAIA at McSweeneys, dedicated to ‘anyone who has ever tangled with an elevator’.

Aside from Stephen King’s The Shining, many film-makers have utilised the horror of elevators, though only non-white creators are accused (benevolently, but powerfully) of appropriation. Aside from the many East Asian horror films themselves (e.g. in The Grudge, The Eye), among the numerous other Western examples we’ve got:

- the elevator chase scene in Silence of the Lambs

- another dangerously transphobic film Dressed to Kill (1980)

- Elevated (1996)

- employees trapped inside an elevator in Resident Evil (2002)

- From Dusk til Dawn 2 (widely regarded as an unnecessary sequel)

- Final Destination 2, which alludes to urban legends about men with hook hands

- The Cabin in the Woods (not where you’d ordinarily expect to find an elevator network)

- Annabelle (prequel to The Conjuring)

- The Night Chronicles 1: Devil (2010) by M. Night Shyamalan

- and numerous others

Perhaps the Stephen King analogy will persuade larger Western audiences to check out the work of Hideo Nakata, if they haven’t already. If you’re brand new to J-horror (Japanese horror), Dark Water is a good place to start.

EXPLAINING THE TITLE “DARK WATER”

- The film is based on a short story called 浮遊する水 in a collection by author Kōji Suzuki. All of the short stories feature water in some way.

- Read: Fuyū Suru Mizu

- Literally, Floating Water

- The short story was adapted for film in 2002: 仄暗い水の底から

- Read: Honogurai mizu no soko kara

- Literally, From the depths of dark water

- Shortened to Dark Water when adapted in 2005 for English speaking audiences by Walter Salles

- There’s also a manga adaptation of the short story collection, illustrated by Meimu.

THE MOTHER AND MOTHERING IN DARK WATER

Before we talk about the depiction of mothers in Dark Water, I feel it’s important to point out that the author Koji Suzuki is not just famous for writing horror fiction in Japan, but also for writing about fatherhood e.g. Kazoku no Kizuna 鈴木光司 (1998), available only in Japanese. He is himself the father of two daughters (now grown).

Centralisation of the mother in Dark Water was novel at the time:

[T]he female hero in [Dark Water] and other films associated with this horror cycle (i.e. the Ringu films, Ju-on and others) is a recent feature of Japanese film culture. In Suzuki’s original novel for the Ring series, the investigator was male. The decision to change to a female investigator was made because the main audience for the cinema in Japan is younger and more used to Hollywood movies.

The Case For Global Film

But is a story feminist simply for putting a mother front and centre?

The primary conflict of Dark Water is that inadequate mothering, brought on by the disruption of divorce or the heroine’s excessive or inappropriate focus on a career, leads to neglect, and possibly irreparable loss. In some ways, the film suggests a certain amount of cultural nostalgia for the past that imagines a mother of myth rather than reality. Its vision of mothering has not adapted to the changes brought on by the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the 1990s, which compelled many women, including mothers, to enter the workforce. As Ruth Goldberg claims, quoting Masami Ohinata,

Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media“When Japanese hear the word mother they do not call to mind the real flesh-and-blood mothers of their personal experience but, rather, see a personification of ‘devotion to children, parental affection, and self-sacrifice.’ … People’s devotion to the concept comes close to that of religious faith.”

The non-supernatural trauma of this film derives from mothers who are not their for their children at all times, and the catastrophic effect of parental divorce.

THE FATHER IN DARK WATER

The actor who plays the horrible father — Fumiyo Kohinata — is a well-known Japanese actor who also makes an excellent job of portraying the very cranky Japanese Prime Minister in The Days (2023), about the days immediately following the Fukushima nuclear disaster of March 2011. He’s also in The Ring films.

This father is fighting for full-time custody of his daughter.

Meanwhile, Yoshimi’s lawyer tells her numerous times that, when it comes to child custody, mothers are always favoured by the courts over fathers, but she is warned that this ‘favouring’ will go against her if she starts acting crazy, basically. The father has gone out of his way to paint his ex-wife as crazy — an accusation levelled against women for centuries. When Yoshimi is cautioned to calm down, she is not psychotic or delusional — she is expressing verboten sadness and rage, stemming from injustice and fear.

DARK WATER AND… KAWAII CULTURE?

Note that the red child’s handbag is an example of a kawaii artifact. Kawaii does not simply translate to ‘cute’. Kawaii has a dark side, which makes kawaii artefacts perfect for utilisation in horror.

Kawaii items are “cute”, sure, but also menacing, unnerving and uncanny. Why? Because cute things beguile us, rather like something offered by a witch. Note that the epitome of kawaii, Hello Kitty, has no mouth and no voice. Like the white rabbit on the red handbag of Dark Water, Hello Kitty is basically hobbled and deformed.

Another feature of kawaii is that we can’t pin it down. What are we looking at here? Kawaii artefacts transgress expected boundaries.

Of course, the West also repurposes items associated with childhood for horror purposes. (There’s a word for that: appurtenances. Meaning, accessories or other items associated with a particular activity or style of living.)

But kawaii artefacts are so much more powerful in this regard.

In America and Europe most horror movies tell the story of the extermination of evil spirits. Japanese horror movies end with a suggestion that the spirit still remains at large. That’s because the Japanese don’t regard spirits only as enemies, but as beings that co-exist with this world of ours.

Kōji Suzuki

THE ARCHETYPE OF THE JAPANESE GIRL (SHOJO)

The shōjo has a special iconic status in Japan. Shōjo can be equated with the Japanese psyche.

Traditionally, liminality has been associated with both [sic] sexes, from young male heroes such as those described in Joseph Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces who undergo various forms of initiation rites, to the Bacchae of ancient Greece or the shamannesses of premodern Japan who exist for sporadic periods outside of mainstream culture.

Recently, however, the notion of the female rather than the male as a conduit into liminality has become more ubiquitous, especially in Japanese culture, with the ascendance of the figure of the shōjo.

The shōjo, as John Treat describes her, is a “barely and thus ambiguously pubescent woman” … who is attached to what could well be called a “betwixt and between culture” — what Treat describes as so-called “kawaii” or “cute” world made up of “cousins, boyfriends, and favourite pets,” as well as stuffed animals and related paraphernalia such as “Hello Kitty,” whose cuteness has taken on almost iconic significance in the leisure world of young Japanese.

Susan J. Napier, The Journal of Japanese Studies Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 2006), pp. 287-310

See: John Treat, “Yoshimoto Banana Writes Home: The Shōjo in Japanese Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan and Popular Culture, 1996

J-HORROR AND THE SHōJO

Susan Napier goes on to say:

While the shōjo has become a ubiquitous cultural staple in Japanese society and literature over the last two decades, she is a particularly crucial figure in the related media of anime and manga, both of which contain genres specifically devoted to the shōjo. Treat’s article, written in the late 1980s, discusses treatments of the shōjo figure that seem essentially positive since they situate the shōjo as a liberating site of play and joyous consumerism, offered as an alternative to the pressure-cooker existence of the ordinary Japanese male’s existence. More recently, however, anime and manga have treated the shōjo in infinitely darker and more complex terms, from the battling shōjo (sentoobi shōjo Utena who wants to change the world in Revolutionary Girl Utena (Shojo kakumei Utena, 1977; dir. Ikuhara Kunihiko), to the haunted, death-ridden figures of Asuka Langley and Ayanami Rei in Neon Genesis Evangelion (Shinseiki ebuangerion, 1996; dir. Anno Hideaki).

Susan J. Napier, The Journal of Japanese Studies Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 2006), pp. 287-310

Napier also offers the example of Serial Experiments Lain (1998) directed by Abe Yoshitoshi. The English-language theme song contains the lyrics “I am falling/I am fading. But Napier is writing a paper on Spirited Away (2001) directed by Hayao Miyazaki for family viewing. This ‘disappearing trope’ happens to Chihiro, too, when her body begins to disappear even as she watches. To save herself she must eat something from this fantasy world.

This is a problematized treatment of the shōjo. Why? Napier offers a theory:

I would suggest that it has to do with an increasing sense of vulnerability and fragility on the part of the Japanese toward their own culture in the 1990s as the economic juggernaut that had powered Japan through most of its postwar years began to sputter and collapse. In this climate of social, economic, and political instability, the iconic figure of a vulnerable young girl, either fighting back or internalizing various dark psychological problems, may have had particular cultural resonance. Furthermore, the liminal condition of the young girl may be seen as a metaphor for Japanese society which, over the last decade, seems to be increasingly in limbo, drifting uneasily away from the values and ideological framework of the immediate postwar era.

It might also be noted that the image of the young girl evokes certain crucial aspects of Japanese cultural tradition. The tenth-century Genji monogatari, the most important text in premodern Japanese literature, is dominated by images of young girls on the cusp of adolescence and ends with a vision of a troubled young girl casting herself into the waters of the Uji River, another liminal image. In the indigenous Shinto religion, especially before the introduction of Buddhims, shrine maidens (miko) had an important shamanic function as mediators to the gods.

Susan J. Napier, The Journal of Japanese Studies Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 2006), pp. 287-310

THE MOTIF OF WATER IN DARK WATER

There’s no water dripping through the ceiling in the original Dark Water short story. This was a motif inserted into the film. However, another short story in the same collection does feature water dripping through the ceiling (“Watercolors”).

Note the importance of seasonality: The story is set during rainy season (tsuyu), when you’d be silly to leave the house without your umbrella because it’s definitely going to rain, and the rain will absolutely soak you. This cycle is very regular — at least historically — and happens between May and August (in notable peaks between June and late July)

As Dark Water opens, there’s a yellow tint to the sky hanging over the preschool — a site of trauma for at least two little girls. As rain falls, note that everyone is wearing light clothes.

Tsuyu in Japan is wet, but it’s also warm and muggy. Mould can be a problem, and presents an especial problem for those charged with the task of cleaning and maintaining bedding and clothing (namely, women). If housewives don’t keep on top of this, mould can literally breakout overnight.

So I feel the horror of humidity plus rain is a specifically feminine horror trope.

But there’s also a historical link between women, girls and drowning in wells…

IS DARK WATER BASED ON A TRUE STORY?

The phrase “based on a true story” is thrown about fast and loose in movie-marketing world.

See also: Episode 9 of the Then Again Podcast, “Based on a True Story”: the ethics of telling true stories in movies. When you see the words “based on a true story” in the opening credits of a film assume that’s Hollywood-speak for “mostly lies”! Using the film “Green Book” and the discussion its Oscar-winning generated as a springboard, in this episode Ken and Glen delve into truth, seeming truth, and cinematic responsibility in film.

THE HISTORICAL REALITY OF GIRLS AND WOMEN DROWNING IN WELLS

In Early Modern England, we know how children died because there are records. While boys were allowed to stray away from the domestic sphere they were therefore more likely to drown outside the home. Meanwhile, girls were more likely to die either by scalding (inside the home) or by drowning in a body of water near the home. Girls were charged with the task of carrying water, even while still very, small, even while malnourished.

In north Wiltshire in 1753 the coroner recorded the death by drowning of two two-year-old boys, one in a ditch, the other in a tub of wort; the following year there were two more such deaths, one in a well and one in a brook. Boys were also killed by carts. The number of girls drowned was smaller, and they most commonly died by falling into buckets and wells rather than into ditches and rivers, suggesting that they stayed closer to home.

Women in England 1500-1760: A Social History by Anne Laurence

Work to do with water was also the main killer of adult women:

A study of accidental deaths recorded in the coroners’ inquests for the later Middle Ages gives a fascinating insight into the way in which real women spent their days. Morning accidents were commonly associated with fetching water and preparing meals, working with livestock and brewing. The number of accidents rose as noon approached and women became tired and hungry. Afternoon accidents were predominantly concerned with laundry or seasional agricultural work. Drowning and burning, and accidents connected with fetching water, and with laundry and cooking, were much the commonest causes of accidental death for women. They took place both in their own homes and in the homes of neighbours.

Women in England 1500-1760: A Social History by Anne Laurence

See also: The Symbolism of Water Wells.

Now let’s look to Japan.

THE ANCIENT JAPANESE LEGEND OF BANSHU SARAYASHIKI

Acourt lady named Okiku who is the victim of an unjust plot to assume the lordship of Himeji Castle. When the castle lord is sick and dying, his villainous chief retainer, Tetsuzan, plans to eliminate a rival heir with the help of Okiku. He tries to seduce her and then blackmail her by framing her for the theft of one of ten treasured dish plates that the heir has earmarked as a succession gift. When that doesn’t work, Tetsuzan decides to suspend Okiku over a well and torture her.

Tetsuzan repeatedly lowers and raises Okiku from the well, deriving sadistic pleasure from striking her with his bokken (a wooden sword used in kendo and other martial arts). The phallic shape of the sword and the whole exercise of moving Okiku in and out of this hole in the ground lends the scene twisted psychosexual energy as if it were a bit of early torture p*rn like Saw.

Okiku refuses to give in and become Tetsuzan’s lover or help assassinate his rival, so he finally knocks her down into the well. Before long, he hears a voice counting plates from the bottom, and Okiku’s spirit rises from the mouth of the well.

Down the Well: The Real Ghost Story That Inspired ‘Ringu’

Although this article describes how the legend of Banshu Sarayashiki inspired Ringu, it’s clear to me that Koji Suzuki was also inspired by the drowning in the well aspect. The ancient well becomes a water tank on the roof of an apartment block just as the spirit of Okiku comes out of the modern technology of a television set in Ringu.

Unfortunately, the link between women, girls, wells and death continues. Let’s take a look at terrible events which have happened even in the years since Dark Water was made.

THE DEATH OF ELISA LAM (2013)

On February 19, 2013, the body of Canadian tourist Elisa Lam (Chinese: 藍可兒; born Lam Ho-yi) was recovered from a large cistern atop the Stay on Main hotel in Downtown Los Angeles, where she had been a guest. She was last seen alive on January 31 and was reported missing by her parents on February 1. Her body was discovered by a hotel maintenance worker investigating complaints of flooding and low water pressure.

Interest in Lam’s disappearance increased on February 13 when the Los Angeles Police Department released security camera footage of her behaving erratically in a hotel elevator on the day she was last seen alive. The video went viral. While an autopsy performed on February 21 was inconclusive in determining the manner of Lam’s death, the Los Angeles County Coroner’s office subsequently ruled the death an accident with bipolar disorder being a significant contributing factor.

Wikipedia

THE DEATH OF DELTA MEGHWAL (2016)

Seventeen-year-old Delta Meghwal was found dead in a water tank at her school in Rajasthan in 2016. The previous day, she had told her parents she’d been raped by her teacher. Her death received far less attention than other high profile Indian murders of young women due to her caste. Men tried to control the story by saying that Delta killed herself after being caught “in a compromising position” with the physical training instructor. No water was found in her lungs. Injuries to her body were inconsistent with suicide. Moreover, Delta’s body was found after a guard opened the tap on the tank.

Delta was a brilliant student and talented artist.

There’s a 2021 Netflix docuseries by the creators of The Ted Bundy Tapes called Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel which over four episodes takes a detailed look at the death of Elisa Lam.

Of course, the Internet noticed the similarities between Lam’s death and the 2002 J-Horror Dark Water. There’s nothing prescient about Dark Water, which instead taps into an ancient reality: Male violence inflicted against women. Women are killed in all sorts of ways by men, so it’s not difficult to find examples of murder which happen to involve water tanks.

Let’s not forget that Lam was a real person as we milk her story for entertainment.

Lam’s death, combined with a long history of stories about girls and young women drowning in wells, has been used as inspiration for further works of horror, notably the “Watershed” episode of Castle (2013). The following year, How to Get Away with Murder used a similar storyline. Also in 2014, the Murphy brothers sold a horror script called The Bringing which is about a detective’s descent into madness as he investigates a death similar to real-life Lam’s. They were criticised for making entertainment by utilising details from a real person’s death so soon after it happened.

The dead-girl-found-in-a-hotel-well plotline has been used nearly every year since Lam’s tragic death and this narrative continues to find popularity with writers and audiences alike.

MORE FILMS AND TV FROM KOJI SUZUKI

- Ringu — The Ring franchise is probably the best-known J-horror in the West. If you’re a big fan of The Ring you may want to check out Suziki’s short story collection called Birthday (1999). Some of those stories are prequels and sequels to The Ring.

- Rasen — based on a 1999 novel. This one gets a pretty high rating from the critics even though it’s been largely forgotten now. This time it’s a professor who gets caught up in a video tape horror by the relentlessly malevolent spirit called Sadako, and if that sounds similar to Ringu, consider this story a sequel to Ring: Final Chapter. It was released at the same time as Ringu in Japan, though the directors and screenwriters are different people. In this one the hapless characters are lucky — they last a full 13 days after viewing, not just a stingy 7. You don’t need to have seen Ringu to understand Rasen as it functions as a standalone story. Rasen means spiral in Japanese. The film also goes by the name Spiral when marketed to English speakers.

- @beibimeru — In this very low-rated film, a woman is found with her abdomen cut open. The umbilical cord can still be seen. That same night, Akemi receives a strange email. A few days later she finds out that she is pregnant, but she knows that this is impossible. Her husband, who is a teacher, is then told a strange story about cursed emails. Beibimeru is the Japanese way of pronouncing “Baby Mail”. (Mail — meeru — specifically means email when borrowed into Japanese.)

- Asoko no seki — In this 2005 film, transfer student Kana Seto is ostracised by her entire class after accidentally sitting in what is called the “Cursed Seat”. In the past, whenever students sat in that particular seat they ended up ending their own lives or becoming neurotic. Kana starts receiving silent phone calls and is sent weird pictures every day. The title means “The Seat Over There”.

- Suzuki Koji: Real Horror — a 2015 limited TV series based on Suzuki’s novel of the same title. Similar to a series like Black Mirror, each episode is based on a different short story. Each story makes use of everyday horror combined with existential dread. A different adaptation of Dark Water is one of the episodes.

- Open Water — Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler) directed another short story from the same Kōji Suzuki short story collection as Dark Water: “Adrift”. The film is only a loose adaptation. In Adrift, fishing boat discovers an abandoned yacht with a strange distress call. A deckhand agrees to take lone control of it while it’s towed into port, but soon he discovers why it is called it a “Ghost Ship.” (Not to be confused with the film based on a true story, starring Shailene Woodley.)

- Eyes — a 2015 film based on a short story. A student is haunted by chilling visions surrounding her, leading to sinister acts that put her own life and those around her in danger.