Where were you when you first watched The Silence Of The Lambs? I was about fifteen, mid-nineties. The film had made it to midday TV. It was a rainy, wintry day outside and my mother sat knitting in the recliner chair. I was on the floor making flashcards for high school Japanese, but as relaxing as I found this task, the film won out that day. The cosiness of my environs juxtaposed against the content of the film stands out in my memory.

Some years later, on a fine Monday morning, I was walking to work and saw a man struggling to put a sofa into a van. He didn’t accept my help as it happens, but I remember thinking to myself, “Don’t actually get inside the van.” Sometimes films do that to you. I can’t see a glass of water wobbling without thinking of Jurassic Park. I can’t see a man loading furniture into a van without thinking of Buffalo Bill.

The Silence of the Lambs mostly holds up to multiple viewings, and maybe even requires it. It took me a while to work out exactly how Clarice got to the right house before her colleagues did, and I’m still not sure I’m meant to know exactly what went wrong there. Here’s the thing about rewatching in 2017, though: It’s clear this film has not helped dominant attitudes towards gender non-conforming people. In 1991 the film-going public didn’t really know the difference between transvestite, transgender, gay and transsexuality. We certainly didn’t give that community a second thought.

Some has been written on this topic already. Key points:

- The Silence of the Lambs demonizes and delegitimizes transgender individuals by portraying the serial killer as a psychotic transgender person. (Hitchcock’s Psycho was bad in a similar way.)

- Transgender women are often represented as psychotic killers as a lazy method of responding to mainstream society’s fear of gender nonconforming people.

- This trope promotes fear by reinforcing the idea that being transgender is unnatural and perverted, and pathologizes gender fluidity.

- In reality, transgender people are far, far more likely to be killed than to be killers.

- In addition to crazed killers, Silence of the Lambs portrays transgender women as imposters. Any story with an emphasis on the transition — the close ups of her putting on lipstick and so on, is pretty much guaranteed to be emphasising an ‘imposter’ view of transsexuality. This is specifically transmisogynist, as trans men are not picked on in quite the same way.

- The writers try to lampshade the transmisogyny by explaining that Buffalo Bill isn’t a real ‘transsexual’ and that real transsexuals are generally gentle people. (I’ve seen this referred to as Jonathan Demme’s fig leaf.) Clarice says to Hannibal, “Clarice explicitly states that, “there is no correlation between transsexualism and violence. Transsexuals are very passive,” expressing one of the sexist requirements to access a diagnosis. Rather than proving the killer here is not transgender, this highlights the reality that transwomen have to conform to feminine stereotypes in order to be granted gender reassignment surgery. Transgender people have also been denied surgery because they have been abused. Many have been abused because they are gender non-conforming, as has Buffalo Bill. This remains the reality for transgender people seeking reassignment surgery today.

- Hannibal replies to Clarice, “Billy hates his own identity, you see, and he thinks that makes him a transsexual, but his pathology is a thousand times more savage and more terrifying.” This quote enforces the idea that other people can determine a person’s gender identity. If Jame Gumb identified as a woman, she was a woman. If a person thinks they are transgender, they are. Hannibal Lecter’s use of the word “more” before “savage” and “terrifying” implies that there are savage and terrifying elements to actual transgender people.

- Though the term isn’t mentioned it’s clear Buffalo Bill is meant to be what’s known in some circles as an ‘autogynephile’. This pathologises transgender women, and describes a ‘disorder’ in which a man is sexually aroused by dressing up as a woman. (The gender inverse here is called autoandrophilia’.) Many people would like to see Transvestic Disorder taken right out of the DSM, but unfortunately that would lead to even less funding for gender reassignments, so other groups oppose its removal at this point in history.

- If we consider this character as a man who inhabits a woman’s body after killing her, this is the ultimate, most heinous form of rape. This character is an extreme representation of ‘male’ violence. That is perhaps the intention, but not the way the character is read.

- Buffalo Bill is supposed to be scary not only because she murders and skins her victims, but because she is male-bodied in women’s clothing. The “cross-dressing” is portrayed as especially sinister and perverted, but to stand or dance in front a mirror with one’s penis tucked between her legs is an exercise many transgender women actually perform. This scene is often touted as the film’s most disturbing moment. In short, a man dressing and posing as a woman is more terrifying for an audience than actual scenes of murder, torture and dead bodies.

- The Silence of the Lambs idealizes normative gender expression. Conformity to gender roles is seen as innocent, an antithesis to gender variance.

- This film is often hailed as a feminist film because of the strength of Clarice Starling, but trans women are women, and need feminism even more than cisgender women.

HISTORY OF THE STORY

The Silence of the Lambs is a novel by Thomas Harris, originally published in 1988. It is the sequel to Harris’ 1981 novel “Red Dragon” and the second book by Harris featuring the cannibalistic serial killer and brilliant psychiatrist, Dr. Hannibal Lecter. The film follows the book quite closely, but one aspect missing from the film is Buffalo Bill’s infatuation with his mother. Despite the fact that his mother abandoned him, Jame Gumb feels an attachment to her. The novel depicts scenes of Jame Gumb watching a video of his mother participating in a beauty pageant. He ritualistically watches the video, rewinding and re-watching certain parts again and again. We see Jame Gumb dancing in front of the TV but we don’t know exactly what he’s watching.

By the early 1990s, audiences had seen a lot of slashers and remakes. They were totally ready for something new and the adaptation of The Silence of the Lambs came along at the exact right moment. Compared to similar films, this story has little in the way of gore and violence. We don’t see Buffalo Bill actually killing anyone. When Clarice is shown what Dr Lecter did to someone, she sees the photo but we only see the look on her face. There’s a post-mortem scene, but we don’t get the same level of gory detail that is often indulged in today. The camera is mostly on Clarice, not the dead body. We do still see the head in the jar. We still see the dead women. But this is not slasher material.

OVER-MOTIVATION OF CHARACTERS

Another big difference between book and film: In the book Clarice Starling is fired from her task. She goes to Ohio on her own dime to catch the killer, sure of where he is. She’s right.

This is Hollywood ‘over-motivating’ its characters. What does that even mean? Writers don’t let the characters of thrillers become intrinsically motivated over the course of a story. Even in the third act they’ll be forcing their heroes to do something even when in the real world of the story, the hero would be doing these things anyway. The screenwriter of The Silence of the Lambs was advised to remove this bit of over-motivation, and he did. The film is better for it. More modern stories such as Homeland and The Killing are still over-motivating their detectives by getting them fired from their jobs.

Be mindful that if you are writing a crime story and you get your detective fired, you’re using an overdone trope. Ask: Is my character already sufficiently motivated to solve this mystery even if they don’t get fired?

AN AWARD WINNING HORROR FILM

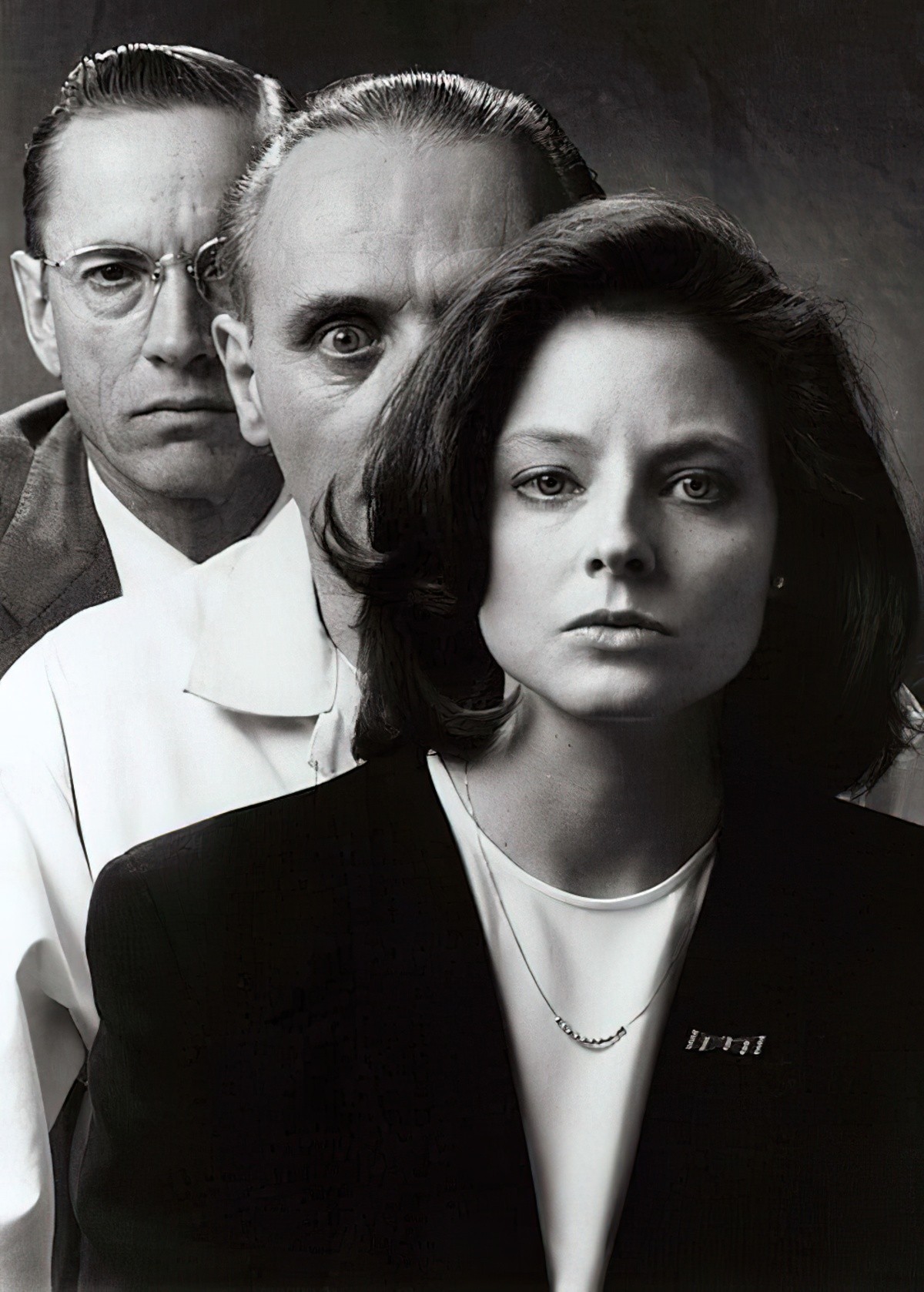

The Silence of the Lambs is said to be the only horror film to win the Best Picture Oscar. And it won a lot more than that: it’s only the third film in Oscar history to take home wins in the Big Five categories, a.k.a. Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay (Adapted Screenplay, in Silence’s case), Best Actor (Anthony Hopkins), and Best Actress (Jodie Foster.)

It’s a bit of a stretch to call this a horror, though. The Silence Of The Lambs is a subcategory of thriller with crime and drama thrown into the genre mix. Award seasons still don’t think much of horror, though this might change. Come 2017, horror looks set to save cinemas from bankruptcy.

INSPIRED BY TRUE EVENTS

Buffalo Bill was based on an amalgamation of a number of high profile killers.

One was Ted Bundy. Theodore Robert Bundy was an American serial killer, kidnapper, rapist, burglar and necrophile who assaulted and murdered numerous young women and girls during the 1970s, and possibly earlier.

Another was Ed Gein — a man who stole corpses from cemeteries, skinned them and cured the skin in order to wear it. Psycho and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre are also inspired by this person.

WHYDUNNITS REPLACING WHODUNNITS

A whodunit (whodunnit) is a type of mystery best described as a ‘mind-riddle’. The reader is encouraged to put pieces together themselves.

A whydunit (whydunnit) is a type of mystery where the audience knows who did it from the outset. Emphasis has now shifted onto how the situation got this bad. In this type of mystery we’ll generally be introduced to the criminal at the outset.

Although it’s easy to dismiss The Silence of the Lambs as a run-of-the-mill whydunnit, it was the first of its kind, breaking new ground in the crime thriller genre in the late 1980s. Until The Silence of the Lambs, readers were used to whodunnits, but not whydunnits. In this new kind of story, the audience knows from (near) the beginning who is committing the crimes — instead, the intrigue comes from why s/he is committing the crimes. There are more whydunnits around now and some have been hugely original and successful e.g. Fargo by the Coen brothers.

FAIRYTALE AND LEGEND AS UR-STORY

The Silence of the Lambs functions as a myth or fairy tale. We have a small society set against the deep, dark woods (which functions the same as a forest). Clarice is the good princess. Beautiful and capable, she has no real moral shortcoming — she only wants to do good. She has a psychological shortcoming — her vulnerability — but apart from that she’s almost a blank slate.

What specific stories were the most influential on The Silence Of The Lambs?

Stories in which good characters make deals with evil characters are preceded by Faust, the main character of a classic German legend. According to this legend, Faust is a scholar who is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life. This leads him to make a pact with the Devil, exchanging his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. “Faust” and the adjective “Faustian” now refer to a situation in which an ambitious person surrenders moral integrity in order to achieve power and success.

In The Silence Of The Lambs, the danger is that Hannibal Lecter will get into Clarice’s head. While there’s nothing supernatural about this, it might as well be — Hannibal has the power to destroy someone’s career at the outset if she does not have sufficient mettle.

TAPPING INTO AMERICAN FEARS

Underworld narratives also formed part of Hollywood’s response to widespread moral panic around ritual abuse and child murder that spread throughout America in the 1980s and 1990s. The horrific sprees of society’s new apex predators like Ted Bundy and John Wayne Gacy, linked to hysterical rumours of organised child sacrifice, inspired a film cycle fuelled by pervasive anxiety that children could be snatched up and borne away to horrible fates in hidden lairs. When Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs swept the 1992 Oscars it was our neighbours or the corner grocer – not the government – preying on our fears.

Demme’s film deftly refashioned the myth of Theseus and the minotaur into a race-against-time manhunt. Cadet FBI agent Clarice Starling pursues a serial murderer who has abducted a Senator’s daughter. To track the beast, Clarice must descend into the den of captured cannibal monster Hannibal Lecter for clues to slay the monster at large, Buffalo Bill. For this underworld quest, Lecter is the pedagogue, not the monster. His role isn’t to eat Clarice (he passes up that opportunity when she ventures within striking distance) but to prepare her for her journey. Lecter provides the ball of string enabling Clarice to venture into the minotaur’s labyrinth and return.

Paul Salmond

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS

Silence of the Lambs is an example of a paranoid thriller. This genre was especially popular in the 1970s, due to living in the aftermath of Watergate. In America there was general disillusion with the government. The stories which emerged were about conspiracies taking place in the shadows. One of the most famous paranoid thrillers is The Conversation (1974).

The paranoid thriller has the same basic structure as a conspiracy thriller.

In a conspiracy thriller, the main character will be a lone person, sometimes part of a very small group, who notices something dodgy, putting them on the trail. Our hero might be a reporter/small time cop/private investigator. They have no clue at first what they’re getting themselves into but they get more and more intrigued. When they do realise the extent of the conspiracy they toughen their resolve, double down and risk life and limb to expose the secrets of the government/corporation. There will be a ticking clock element, as this person races to expose the truth before getting found. These heroes aren’t always successful.

Silence Of The Lambs is the daughter of this movement, written in the 1980s. Clarice Starling is not exactly amateur but she is naive because of her freshness and youth and because she is still a graduate student. These stories are conservative in their message (like all thrillers): Bad people cause bad events. Good people identify and defeat them.

Broken down into steps, the story structure of a conspiracy thriller goes like this:

- Starts with an injustice which is externally motivated rather than internally — Clarice receives a call to action. She is being sent on a mission by a man she must obey, though she doesn’t know exactly what the mission is at first. The mission is to stop serial killers, and one in particular. The injustice is clear: women are being tortured then murdered.

- Overconfident investigation — Clarice has shades of overconfidence. She is a proud graduate of UVa, so she tells Hannibal’s slimy doctor, but this is tempered by the fact she is being objectified because she is a young woman and the man deserves what he gets. I put it to you that female characters can’t be written to be as cocky as male characters without losing likability.

- Midpoint disaster — Hannibal murders two guards, the ambulance staff, a tourist and makes a clean escape.

- Overconfident Investigative Crusade — The FBI are confident they have cracked Hannibal’s code and blunder overconfidently towards the killer. Clarice’s boss even calls her to tell her everything has been solved, counting his chickens before they’ve quite hatched.

- Disaster — The FBI goes to the wrong house which almost leads to Clarice Starling’s death.

- (External) Betrayals, in which the hero learns who their real friends and foes are — Hannibal reveals convincingly that he won’t come after Clarice. Clarice knows that he respects her too much. This foe is just as much friend as he is foe, which is an interesting and novel take on the basic friend/foe dichotomy.

- Revelation — Hannibal Lecter has left the country and is not only starting a new life for himself but is back to his evil, cannibalistic ways.

Other Storytelling Techniques

- Clarice Starling has a clear ‘ghost‘. The death of her father and the subsequent experience of being unable to save the lambs.

- The desire lines of both Clarice and Hannibal are equally strong. These goals are articulated clearly. Hannibal tells us Clarice wants ‘advancement’. He is correct, though as Clarice doubles down she also wants to do good. Hannibal wants to escape Dr Chilton who makes his life a misery. He also wants a window, but his unstated desire is to play psychological games with people. What Hannibal says he wants is only his most surface level desire. Clarice’s supervisor points out what he really wants by explaining Hannibal’s psychological profile.

- As soon as the audience knows exactly what each wants, it’s only then that the film switches point of view and we’re taken to the scene of Buffalo Bill’s latest crime, where he lures the woman into the van.

- There is a strong character web around Clarice, who faces multiple opponents of different kinds. There’s the slimy Dr Chilton, Hannibal himself, who is in some ways more like a fake opponent ally. Then there’s the untamed monster out there in the wild, Buffalo Bill.

- The Silence of the Lambs doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test — Clarice is shown to have a close female friend (whose name I can’t easily find), though they’re only ever shown talking about a man — Hannibal. Which is fine. The main function of the female best friend is to fulfil the part of the story where a mentor/friend character asks the main character if what they’re doing is really such a good idea. This is the part where an ally becomes the conscience of the hero. The BFF asks Clarice, “How do you know he won’t come after you?” She’s actually lampshading the conscience of the audience. This is what we are wondering. Clarice then has the opportunity to reassure us that he won’t.

- The big audience revelation comes pretty early, which is what marks out a whydunnit from a whodunnit. We see Buffalo Bill. So what keeps us watching for the second two thirds of the film? What revelation are we rewarded with? We learn before Clarice the true power of Hannibal Lecter when he escapes from that high security facility. We also know a few moments before Clarice does that she has made it into the monster’s lair and is in great danger.

- Sure enough, the writers take Clarice right to the edge of death. She literally has a gun pointed and cocked at her back. She saves herself only by her quick reactions. (“If you’re gonna shoot, shoot!” This is a well-worn trope in film, where someone can easily shoot someone but hesitates for unclear reasons and then ends up being shot themselves.)

- When Clarice receives kind words from her supervisor we know she has made it as an FBI agent now. She has what it takes. She knows it, too.

THE CHARACTER OF CLARICE STARLING

Clarice Starling has had an undeniable influence on female heroes in pop culture in general. She is said to be a feminist character. But Clarice is not a ‘feminine’ character. She is the same male hero we’ve seen many times before, only in a female body. Clarice in fact follows the mythological hero’s journey in fairly traditional ways, though it is a woman here descending into hell – Bill’s basement – to rescue the damsel in distress. This story is the classic Hero’s Journey. It is not an example of a Female Myth. We are only just getting those kinds of stories now.

Main Character Description: “This is CLARICE STARLING – mid-20’s, trim, very pretty.”

This video by Now You See It talks about the opening scene of The Silence Of The Lambs. We see Clarice Starling emerge up the middle of the screen from the bottom. This is Clarice pulling herself out of a rut. We see from the outset that this character is trying to overcome a personal hurdle on her own. Notice the rope beside her. Not everybody has made it as far as she has. Once at the top of the incline she pauses to hear birds fly and to watch them. Birds flying symbolise freedom our hero has achieved by making it to the top.

Clarice has a symbol attached to her character: Lambs. Lambs are a symbol of innocence. Starling’s inability to save them and her subsequent nightmares are manifestations of her guilt. The film’s title is a reference to the end of Starling’s nightmares, when the screaming lambs become silent, ideally through her solving the Buffalo Bill case and saving his living victim, Catherine Martin.

The problem for writers when creating a paranoid/conspiracy thriller is that the main character is often too passive. Everything happens to them. It’s a very tricky genre to write for this reason. These heroesare the most alien to human nature of all the story types. e.g. Someone wants to kill me; I’m going to kill him instead. In real life that doesn’t happen. You’re going to call the cops. So you have to spend a lot of time coming up with reasons why they can’t call the cops. However! This hero does not suffer from that problem. Monster movies do not suffer from this problem either, and Hannibal Lecter is a monster by any definition. Everything Clarice Starling does feels like a natural consequence of the position she finds herself in. Clarice is intrinsically motivated to solve the mystery of Buffalo Bill’s identity. Her backstory of the screaming lambs is improbable as a motivation that lasts a lifetime, but works well enough for story purposes. (I’ve heard a flock of chickens being murdered by a fox, but this hasn’t provoked me to want to join the police force and hunt down serial killers.)

In his book The Secrets of Story, Matt Bird advises writers to give main characters a false statement of philosophy at the beginning of a story (if any is given at all). This is so we can see how much they change between the beginning and end.

Silence of the Lambs is an example of a character who doesn’t have a false statement of philosophy but accepts a false piece of advice. Clarice’s boss, Crawford, gives her one cardinal rule for dealing with Hannibal Lecter: “Don’t let him get into your head.” In the end, she will realize this is precisely what she needs to do.

THE CHARACTER OF HANNIBAL LECTER

REFLECTION CHARACTERS

Hannibal is Clarice Starling’s ‘reflection character‘. This is David Hauge’s term for ‘the character who is most closely aligned with your hero –- the best friend, partner, mentor or spouse whose primary function is to help the hero achieve the outer motivation and to urge the hero toward transformation.’ The reflection character, by this definition, is an ally.

A typical role for a reflection character is that of mentor to the hero – a teacher, trainer, coach or therapist whose job is to give the hero the skills necessary to achieve her goal. Hannibal is very clearly a mentor to Clarice, even more than her designated supervisor at the academy.

Reflection characters who are teachers are usually introduced after the beginning of the story – often around the first key turning point: the 10% opportunity. This allows the reader and audience to become acquainted with the reflection as the hero does, rather than having to fill in the blanks of an existing relationship, as with a “best friend” reflection who has been aligned with the hero for some time. The writers followed this guideline when introducing Clarice first, then Hannibal later. We meet him when Clarice meets him.

The reflection character’s primary goal is to help the hero achieve the outer motivation. But does Hannibal really want Buffalo Bill to get caught? I believe he does. If Hannibal himself has to spend years in prison, why shouldn’t Buffalo Bill? Also, I’m sure Hannibal wants to see this hunt to its conclusion as much as we and Clarice do — if only for his own amusement. In this respect, the audience is more like Hannibal than like Clarice. We are here for amusement purposes. We are actively enjoying Hannibal Lecter’s immorality, just as he enjoys the crimes of Buffalo Bill.

Hannibal is an excellent reflection character because here is another hard and fast rule for reflection characters: There must be lots of conflict between the hero and this character. The reflection character pushes the hero beyond their limits. At some point in the story, the hero must reject the reflection character completely. Despite rejection, the reflection character must remain loyal to the hero. Clarice Starling (a character herself) understands and relies upon this rule of characterisation in storytelling. When she says Hannibal respects her too much to come after her we know that she is right, because we’re subconsciously primed to expect this from a reflection character in stories. As you can see, Hannibal fits this character pattern perfectly.

When the mentor is a male and the mentee is female, this is often a take on the Pygmalion story. A man creates a woman into the perfect image and falls in love with her, not because she’s a person in her own right but because he is proud of his creation. We rarely see the gender flipped in a Pygmalion story.

HANNIBAL AS TRICKSTER

Audiences love tricksters. Hannibal is a classic trickster, laying down little puzzles and offering anagrams. He is also a deadly trickster, somehow doing magic with the key to his handcuffs in a Houdini-like act. Despite his immorality, it is satisfying to see Hannibal get out of that prison. It is equally satisfying to see Clarice solve his puzzles, and we see how clever she is. She therefore deserves to succeed.

WHAT MAKES HANNIBAL SO SCARY?

(Apart from Anthony Hopkins’ acting, of course, when even had an impact on the actor’s personal dating life.)

We know right from the start that Hannibal eats people in Silence of the Lambs. It’s why he’s been locked up for eight years. Clarice Starling is more than prepared to deal with a monstrous cannibal killer, because this aspect of Hannibal isn’t a secret. He eats people. That’s not the scary part. That’s not what instills a sense of dread in us.

A lot of modern horror relies on the jump scare, the unknown, the mystery. Hannibal, in all his iterations, has never been this way. We know exactly what Hannibal is capable of, and that heightens the horror in a different way for us. There’s fear of the unknown, and then there’s fear of knowing exactly what to expect, and when it’s something as gruesome as having your face eaten off, the distinction is minimal.

Beyond the fear of the known and the dread of a cannibal killer mastermind, the strongest aspect of horror Hannibal’s character holds for us is how much he is needed throughout The Silence of the Lambs. Clarice goes to him to learn more about Buffalo Bill, enlisting his help. The idea of us needing the monster is nothing new, but when that monster is a man who would cook and eat your delicious organs if given the chance, having to trust him to deliver valuable information does give one pause. What are we doing if we are relying on the kindness of monsters? Trusting the information of supposed pure evil? What does that make us?

New Media Mayhem

A STORYTELLING LESSON ON THE LIMITS OF SYMBOLISM

The symbolism in The Silence Of The Lambs is all extremely obvious. From the way Clarice squeezes into that storage facility, lifting the door herself with no help from the men standing nearby, going in ‘from the bottom (ranks)’, giving herself a minor wound in the process, to the heavily symbolic names (Starling = bird = flight = freedom).

Obviousness in itself is not a bad thing. Opaqueness is in fact overrated in storytelling.

However, in this particular story, symbolism is used not only to convey character motivation but also as a bandaid to cover what is otherwise a problematic trope. Moths. Men acting as women. The symbolism has its limits. The moth is not trying to become ‘something it’s not’ when it matures. It is becoming what it was always destined to be. The message about this man dressing as a woman, however, is very much the inverse — Buffalo Bill was never meant to be a woman, so we are told.

The book especially, but also several parts of the movie, expose that Jame Gumb hates him/herself and desires change, which inspires his obsession with moths. S/he breeds Death’s-head Hawkmoths in the basement, frequently observing them. S/he then inserts a moth chrysalis into the throat of each of the victims.

Dr. Lecter explains to the audience what this obsession is meant to represent: “The significance of the moth is change. Caterpillar into chrysalis or pupa. From thence into beauty. Our Billy wants to change too.” Lecter spends the majority of the movie subtly expressing Jame Gumb/Buffalo Bill’s intense self-loathing and desire for complete metamorphosis.”

As you can see, there’s nothing deep and obscure about this symbolism. It’s right there on the page and screen. The audience does not need to remember anything from high school English before understanding the connection between the moth and the man transforming into the body of a woman. Here’s what director Jonathan Demme said about criticism of his film from the LGBTQ community, many years later:

So, Gumb is not gay, but there is a reference to a homosexual experience he had which is attributed to this quest. We were all banking a little too much on the metaphor of the Death’s-head moth—that Gumb is trying to achieve a metamorphosis through making his human suit. We didn’t fortify and clarify that enough.

director Jonathan Demme

I disagree with Demme on this point. It’s not that he didn’t clarify the metaphor enough. All this ‘change symbolism’ could not have been more obvious. The problem is with the entire trope of Buffalo Bill, as outlined above.

By the way, it wasn’t just the moth which symbolised transformation. Buffalo Bill’s tattoo is another attempt at reinforcing the symbolism of dichotomy: the tattoo is Jesus’s side pierced by the Spear of Destiny, where blood and water supposedly flowed out of him separately.

Symbolism, even in its most obvious form, won’t get you out of a hole if your story serves to reinforce problematic tropes which marginalise entire groups of people.

MONOLOGUE AS COMPLETE STORY

The trick to writing a good monologue? The monologue itself has to be a complete story in its own right.

Take Hannibal’s monologue in which he delivers his first string of insults to Clarice.

1. Shortcoming

Afraid of being disrespected. “You think you can dissect me with this blunt little tool?”

2. Desire

To play a game with Clarice for his own amusement, unsettling her like this to see if she’s up to the challenge of finding Buffalo Bill.

3. Opponent

Clarice is a fake-opponent.

4. Plan

He plans to really upset her to see if she’ll stick around for the long haul.

5. Battle

He’s dishing out nothing but insults the entire speech.

6. Anagnorisis

It’s Clarice who has the anagnorisis — she realises who she’s dealing with.

7. New situation

Clarice can now start to interact with Hannibal knowing more about the way he operates.

PACING AND SUSPENSE IN SILENCE OF THE LAMBS

This film is held up as an excellent example of suspense. But is that what really makes this film so enjoyable, or is it something else altogether?

There’s an argument to be made that The Silence of the Lambs is not all that suspenseful:

The Silence of the Lambs is that it is almost totally lacking in suspense.

Suspense was deliberately sacrificed on the altar of momentum. “Again and again,” according to the film’s writer Ted Tally, “both during our script work and later, during editing, [Demme] emphasized the supreme value of narrative momentum. ‘Better,’ he said, ‘to risk confusing the audience for three minutes than to let them get ahead of us for one second.’”

The Silence of the Lambs tells its story at two speeds, fast and faster, and when it gets faster, it’s usually trying to paper over a hole in the plot by misdirecting the audience. Such tactics, while diverting on the first bounce, just seem protracted and uninspired in a repeat viewing, and they drastically harsh the film’s overall tempo.

Nicole Gagne

The scenes cross-cutting the FBI raid into an empty house with Clarice’s entry into the lair of Buffalo Bill is held up as an excellent example of cross-cutting. But is it really all that masterful? Would Hitchcock have done it better?

The swift becomes sluggish: Once you know you’re watching people on a wild goose chase as they climb down an elevator shaft or surround the wrong house, those cutaways seem tedious. But you can’t ask an audience to believe that one lone FBI agent can find the killer’s house in Ohio, walk up to it, and knock on the door by herself, after everyone’s been knocking their brains out searching for him. It would come off as the last-reel cheat that it is, without the distraction of intercutting the FBI’s erroneous raid on a house in Illinois.

Even worse is the way Hannibal Lecter escapes from incarceration – the film’s shakiest example of velocity over intelligence. Lecter has (off-camera) killed his guard, switched clothes with the dead man, peeled off his face, and deposited the corpse atop an elevator. He is found lying on the floor, assumed to be the wounded guard, and removed in an ambulance while the police hunt the elevator shaft for the corpse in Lecter’s prison uniform. The audience doesn’t know what has actually been going on until Lecter, inside the ambulance, removes his face mask and leans in to eliminate the EMS attendant.

Nicole Gagne

FURTHER READING

REFRIGERATOR MOMENTS

Refrigerator moments are not actually a problem. They don’t stop an audience from enjoying a thriller in the moment. This is a Hitchcockian term which refers to when someone from the audience grabs a drink from the fridge after the film has ended and realises that one of the plot points doesn’t add up.

How long would it take an EMS attendant to realize that the patient isn’t hurt? Eight seconds? 12? So the film dodges the issue by accelerating the tempo and intercutting the red-herring search.

But again, would Hitchcock have done the ambulance sequence better?

Alfred Hitchcock always insisted, “You can only get the suspense element going by giving the audience information.” The first thing Hitchcock would have done would have been to let the audience know that it’s Lecter, not a wounded guard, lying on the floor. Then Lecter’s journey from the floor to the ambulance could be mined for two levels of suspense: the killer’s jeopardy at being discovered, and the cops’ and the EMS attendant’s jeopardy at being so close to this homicidal maniac. […] If intercut with this new scene of Lecter on the floor, all that [police raid] footage could contribute its own suspense: How soon before these cops realize the corpse is the guard and Lecter is still in the building?

Nicole Gagne

Tonight, I talk about our love for horror and true crime, and ask: what makes a story truly frightening, instead of just entertaining? What kinds of movies or books, or ways of storytelling, take us beyond entertainment to true horror, to actual fear? For instance, how does the disturbing story of Ed Gein end up, filtered through convention and expectation, as “standard” (even if classic) movies like Psycho, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and The Silence of the Lambs?

Human Voices Wake Us