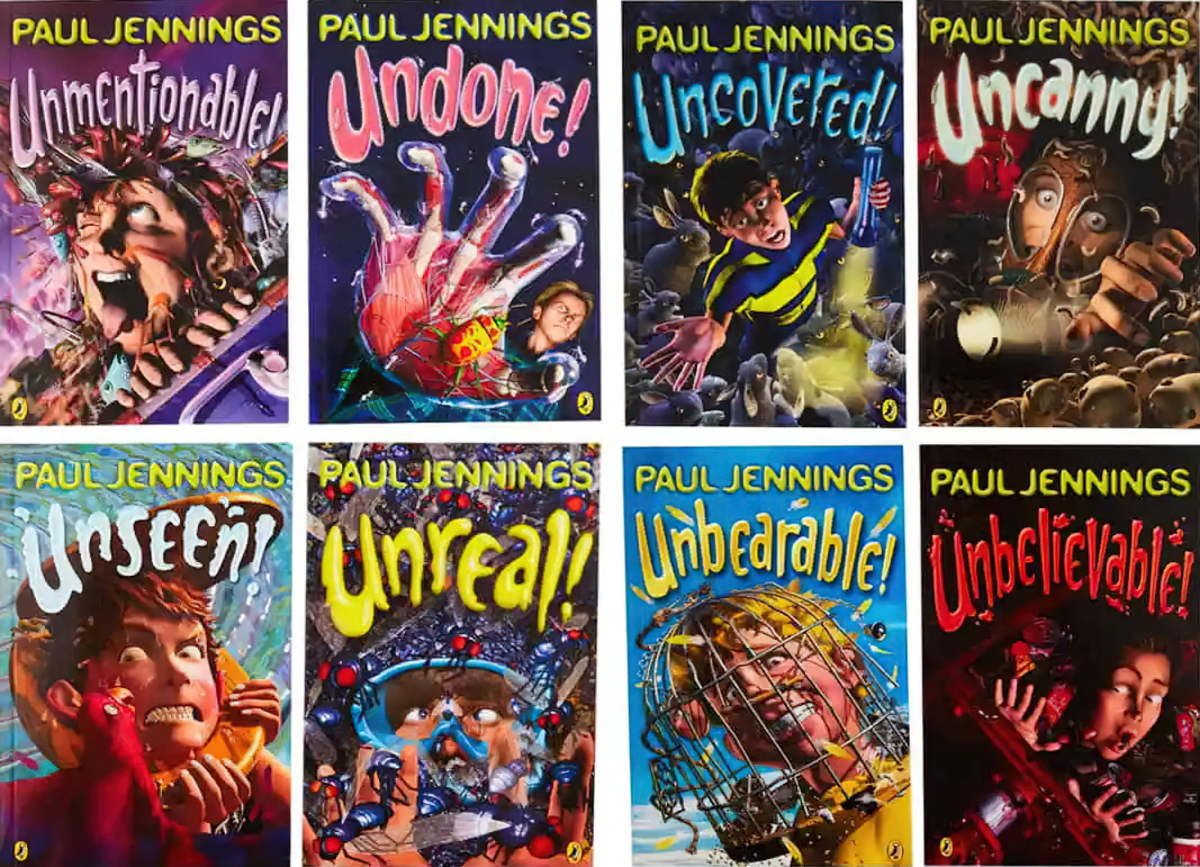

Paul Jennings has been an influential children’s author in Australia and New Zealand since the 1980s.

A PUBLISHING SUCCESS STORY

The Un-series took off internationally, became a TV series, the rest is history. Many people my age grew up with Paul Jennings. Schools across Australia and New Zealand all have (or had) multiple copies, sometimes class sets for study in class. I have taught Paul Jennings stories myself. These are considered texts to draw the reluctant reader in.

After revisiting the tales this year, I realised something else. Jennings’ stories serve to uphold a system of misogyny and sexism typical of the 1980s. Paul Jennings stories served a specific purpose in a specific era, but it’s now time to retire these books from the classroom. Childhood is very short, in comparison to the sheer volume of reading material available. We desperately need contemporary, woke, diverse, feminist hi-lo readers with fun, twisty endings to fill the Paul Jennings space.

Jennings has recently written a memoir. He has this to say about his own work:

[T]he themes of his own childhood have crept into his work, even against his own will at times.

Bullies often get their comeuppance, for example.

Grifters, narcissists and conmen also cop it.

Perhaps more tellingly, parenting crops up a lot.

“There’s a theme which comes up all the time, which is the separation of the parent and the child,” Jennings says.

“And it’s an incredibly powerful thing, because the loss of a child is enormous to a parent. And the loss of a parent is enormous to a child.

“That theme, I realised after a couple of years, it was poking its nose up quite a bit. And I kept saying to myself, ‘I’m never doing that theme again’.”

ABC News

There is also a story Jennings wishes he hadn’t written. “No Is Yes”.

The fact is, culture changes, authors change. This is not the only story I personally wish Jennings hadn’t written.

All that said, Paul Jennings is a master storyteller who cracked the difficult knack of genuinely writing for children, not for a dual audience, nor for advanced middle grade readers only. There’s a lot to learn from Paul Jennings in that regard.

FEATURES OF PAUL JENNINGS SHORT STORIES

STORY STRUCTURE AND NARRATION

- Titles often have a pun element, not obvious until after the twist.

- Opening sentences often introduce intriguing high concepts.

- Or, the story will open with a character in a scary/impossible situation e.g. perched high on a ladder (“Eyes Knows”). In other words, Jennings is making use of in medias res. We continue reading to find out how they got there.

- Or, there will be a weird scenario (a character has a huge nose) and the backstory that follows will explain how this happened.

- Or, the story will begin with a boy having just got himself into trouble with an authority figure (“UFD”).

- Many of these stories are tall tales, and use the techniques of that genre.

- Some are retellings of classic stories or a new spin on an old yarn. “Ice Maiden” = the Greek myth of Pygmalion. “Greensleeves” is a spin on “Jonah and the Whale”. “Know All” is a new spin on Pandora’s Box.

- A lot of Jennings’ stories are bookended. He loves the story-within-a-story structure. To use the terms of narratology, Jennings makes use of two diegetic levels — diegetic and metadiegetic. This conjures the ambience of a ‘storyteller around a campfire‘. Either an interesting adult tells a tall story to a child viewpoint character, or the child viewpoint character themselves launches into some wild backstory to explain the situation at hand. The stand-out example is the standalone story illustrated by Terry Denton, called Sucked In. The story’s title comes from the fact that a group of kids have been taken in by a tall tale… or have they?

- The bookend story has a story structure all of its own. (Its own opponent, plan, big struggle etc.) Because we have two of everything, this packs a lot into a short story and creates a fast-paced reading experience.

- The Battle sequences are especially fun for the audience of these stories, with massive high-octane, ridiculous hilarity and plenty of revenge against authority and outright villainy.

- Stories are written in first person, unless there’s some reason to write in third. For instance, the story will be written in third person if the first person viewpoint character isn’t going to be sticking around for the entire story. (“One-shot Toothpaste”) Stories are also written in third person if there are two main characters instead of one (e.g. “Birdscrap”), or perhaps if the story is about an adult rather than a child (“The Velvet Throne”).

- Jennings doesn’t care that his Chekhov’s Guns are wholly unsubtle. If a character mentions a valuable painting, you can be sure that valuable painting will be found at the end of the story (“Skeleton On The Dunny”). A young reader is in the moment. Unlike a more sophisticated audience, they are not picking up the Chekhov’s Guns and making predictions.

- It’s interesting to see which dots are joined for the young reader. Paul Jennings likes the reader to piece together their own endings. But everything else is handed to them on a plate. For instance, if there is a ghost, the reader is told there is a ghost. (Jennings avoids what some writers call Mystery Boxing.) There’s no doubt about it (to my mind) because Jennings is using all the ghost tropes. But Jennings never forgets: He’s writing for eight year olds. Eight year olds haven’t got a long history of hearing ghost stories. Eight year olds don’t have a long history of anything. They’re eight. This is why, in a story like “Lighthouse Blues” we have sentences like ‘It had to be ghosts. The ghosts of Captain Rickard and Alan Rickard’. Any adult reader has already worked this out by section five. And so have the young readers, probably. But young readers like this confirmed. They were right! They feel smart. In a story for older readers, this sort of explanation might be considered ‘overexplanation’, and edited out.

Don’t play it too cool. Don’t trust us to figure it out if you can’t trust us to figure it out. Always try to think of any other interpretation that your reader may have. When in doubt, spell it out.

Matt Bird

- Paul Jennings doesn’t lampshade coincidence. He makes the most of it. That is a feature of the tall tale. Almost all of his stories contain an element of unbelievable coincidence. Or, to be kind, we could call it ‘non-mimetic’ coincidence. (Events in a story don’t even try to emulate how the real world works.) The events of “Greensleeves” rely heavily on comical levels of coincidence, reminiscent of a fairytale.

- Jennings is using “fairytale logic” and also fairytale archetypes. Mothers are often dead. The boy main character is most often reminiscent of the underdog third son. Virtue is richly rewarded by some unseen force.

- Oftentimes the Battle sequence is a prearranged competition (“Birdman”, “Wunderpants”, “Little Squirt”) in which boys big struggle for prestige and dominance. The underdog will win after previously stumbling upon some magic. It might be a speech in front of the class rather than a competition (“Without A Shirt”), but the story structure is the same.

- Ticking clocks come in various forms, but Jennings likes to make use of a magical piece of equipment which only lasts for a certain number of times or a certain length of time. (Super glue which only sticks for two hours; a lie detector that only works seven times.) This, too, is from fairytales. A genie grants three wishes, etc.

- If a ghost is going to appear, often there’s a character who appears first to explain the backstory of the ghost. (The police officer in “A Good Tip For Ghosts”, the annoying girl classmate in “Cracking Up”.) This utilises the trick of having characters talk about an intriguing character before that character appears on the scene.

- In a Paul Jennings story the planning step isn’t necessarily an obvious step in the direction of fulfilling the main character’s desire. For instance, a boy wants to prove a flying dog exists. Instead of making a plan to that effect, he goes along with his father to buy ice-cream. A boy wants to get out of trouble for ruining his mother’s precious notebook. The grandfather just happens to turn up so he goes along on a frog-finding mission with him. This goes against how most writers cover the plan phase of a story. But in a way, it’s more mimetic for a child audience. A low mimetic child hero doesn’t have great executive functioning, and neither does the typical reader. Kids like this aren’t up to making plans. Instead, everything fits together as if by fate. The boys in these stories fulfil their desires, but often it’s through no good planning of their own. These white boys get what they want through sheer ‘dumb luck’, as Professor McGonnagal might say. (And I do say ‘white boy’ for a reason. We accept that kind of privilege in white boy characters.)

SETTING OF PAUL JENNINGS SHORT STORIES

- Magical items appear without explanation. Magic simply is. In common with fairytales, we are given the very basics, then left to imagine the rest. In “Birdscrap”, Jennings doesn’t bother going into backstory of why a pair of rubies are significant. They just are. We know they are special precisely because the main characters are looking for them. The item with magic attached is common in fairytale and children’s stories but we sometimes see it in stories for adults, such as Annie Proux’s “A Pair of Spurs”.

- A magical item will help the main character achieve their goal, but first they need to learn how to use it. The magical item will lead them through a series (probably two) humiliating gag scenes before helping with the goal. (“Birdman”, “The Mouth Organ”, “Spaghetti Pig-out”). This avoids the trap of magical items all writers need to skirt around — the character needs to save the day, not the magic. This magical item might be a machine typical of 1980s technology, like the VCR of “Spaghetti Pig-out”. A modern audience may not have seen the rewind function in action. More to the point, many modern remote controls (e.g. PS4) don’t need to be pointed directly at the machine.

- Fantasy creatures appear, special rubies exist, and mundane objects have a fantastical backstory. In this respect, Paul Jennings is the kiddie equivalent of Stephen King. For instance, both Jennings and King made use of a monster inside a drain, around the same time. The everyday world is simply a veneer masking terror below. They both make use of the snail under the leaf setting.

- Jennings tends to give a ‘standout detail’ rather than creating a rounded picture. One of the more lengthy examples is the description of the annoying little helper called Snookle, who turns up inside a milk bottle. ‘All I could see was a large pair of gloomy eyes. He must have had a body but it was nowhere to be seen. The eyes simply floated in the air about fifteen centimetres above the bottom of the bottle.’

- Overall, there’s a distinctly Australian feel to the settings (of course). This mapped equally well onto my New Zealand childhood, with its strong beach culture and houses which tend to be near the sea. Beaches hide buried treasure. Where the land meets the sea is often used in stories to evoke that liminal sense of where fantasy meets reality.

- A form of magic beloved of Paul Jennings is the magic which takes over control of a boy’s body. (“Without A Shirt”, “Birdman”)

- A similar form of magic is when a boy feels compelled to do as a magic item tells him. (“On The Bottom”, “Eyes Knows”)

CHARACTERISATION

- The typical reader is an 8-10 year old, and the typical age of a main character is 14-16. This affords the characters more freedom. Some characters are younger than that. It seems to depend on whether there’s a romantic element. If Jennings needs a romance plot, he’ll age the main character up.

- Wish fulfilment in Paul Jennings stories cover a large repeating territory: the wish to be respected (especially by girls), the wish to have money or treasure, to fly, to solve a mystery by your very own detective work, to have super powers, to find a magic item which solves a large problem.

- Main characters are overwhelmingly boys. These boys are low-mimetic heroes according to the scale proposed by Northrop Frye. These boys are slightly more hapless, stupid, unobservant than the reader. This creates empathy, and we also laugh at them. We feel smarter than they are for working things out before they do.

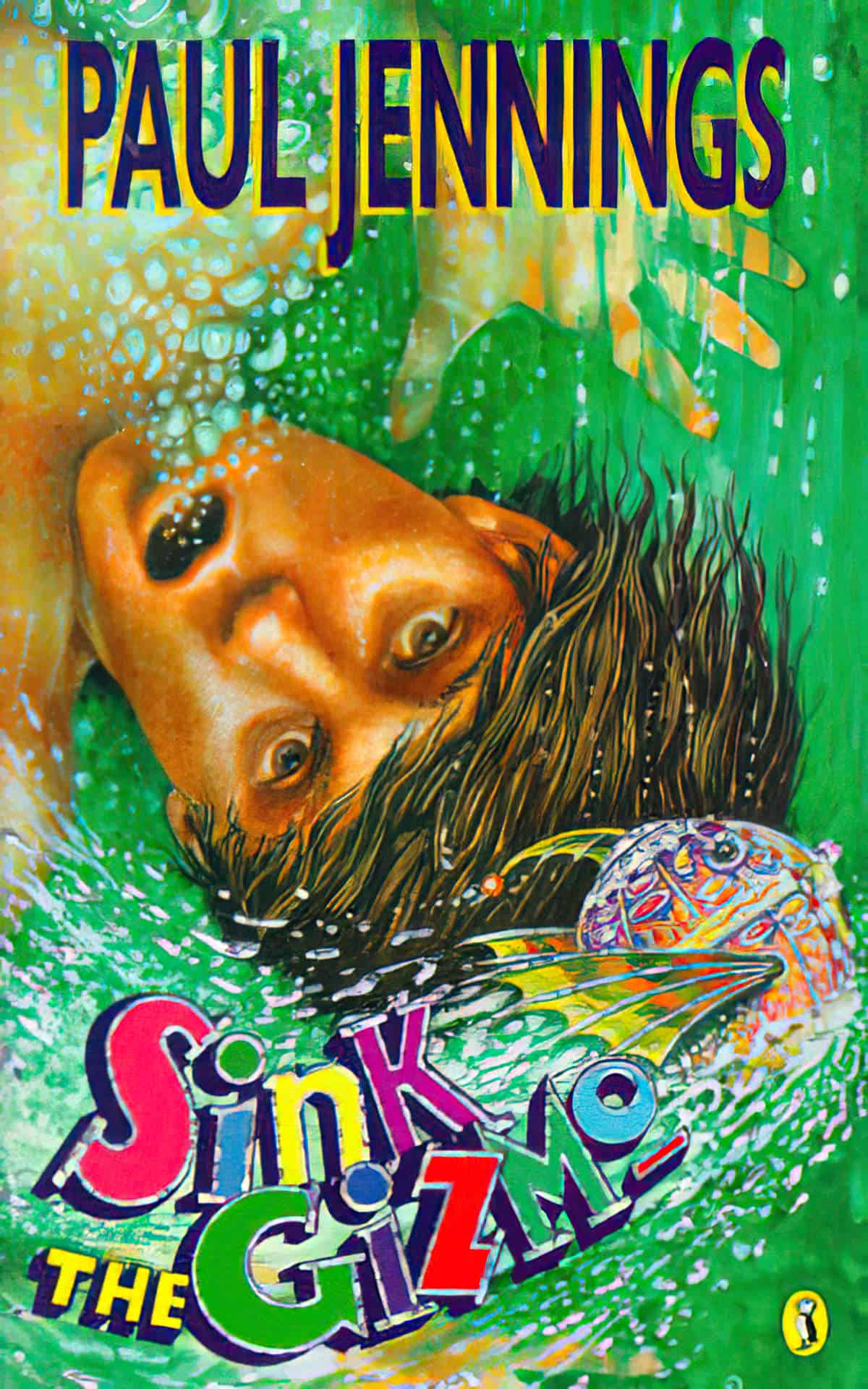

- Paul Jennings gets the parents out of the way and he doesn’t care how he does it. (The parents in Come Back Gizmo have gone out and haven’t even told their son where they’ve gone.) Jennings can get rid of adults suddenly with a one-sentence explanation. Or, we simply accept that parents aren’t there. In fairytale tradition, parents might have died in a car crash.

- Adult opponents are often authority figures (principals, teachers, mean nurses, cranky neighbours). The meanest will receive punishment at the end, with vengeful plot ‘twists’.

- Nasty opponents are both nasty and illogical. For instance, a nasty teacher has a precious plant, yet entrusts the care of it to his students each night so it doesn’t get covered in dust while the cleaners are doing their jobs (“Cracking Up”).

- Jennings likes the archetype of the “little man” (described thus) who appears out of nowhere to serve whatever purpose Jennings sees fit. The “little man” in Come Back Gizmo appears to say the main character’s dog has been found. The “little man” in “Box Strap Flyer” appears as a trickster to outwit another trickster. Why does Jennings describe these men as “little”? Because they are meant to work mostly invisibly, behind the scenes, popping in occasionally to interfere with the machinations of a mystery.

- When girls appear, they are most often girl archetypes (beautiful bitches, blonde sexual objects, wimpy, annoying sisters). They are therefore most often an opponent, romantic or potentially romantic, despite lack of interest on their part. When there are no girls at all in the story (“The Paw Thing”) Jennings doesn’t have the opportunity to muck it up.

- Even adult women are a continuation of the female maturity principle, in which men and boys embark on these wacky, dangerous plans while the women tut-tut, oblivious to the fantasy world around them. In “Birdman” the mother is in a strop with the father because she thinks the flying competition is too dangerous. In “Spaghetti Pig-out” the mother gets into a strop because the father has bought a dodgy video down at the pub, but the father is always vindicated, because these machines and tricks always turn out to fix a big problem. Crazy dads are rewarded. Sensible mums are proven wrong to be sensible, every time.

- Because this is the 1980s, the mothers are the ones calling their kids in for tea. The dads are the ones going out to work. This is believable for the 1980s, but my own mother went out to work in the 1980s, and so did the mothers of most of my friends. So Jennings was still behind in his parental gender roles.

- Characters are often symbolically named e.g. a dog called Ripper who rips holes in your pants, or Chomper, a ghost who (it is revealed) searches the tip each night in search of his false teeth. The big, bad opponent in a story is most likely to be symbolically named in this way. The Every Boy gets more of a classic white boy name.

- The son or daughter of the mayor is likely to be corrupt.

IDEOLOGY

- Inversions are utilised as gags. For instance, a boy and dog switch bodies (Gizmo Come Back) or a father and dog switch bodies (“Birdman”). (See also: Inversion does not equal subversion.)

- Typical of men of his era, Jennings fails to subvert some troubling, misogynistic tropes. Instead, his stories serve to keep girl characters subdued and under control. Yet he is able to subvert other kinds of authority by making the most of the carnivalesque. (“Lucky Lips” is perhaps the worst of the lot, with a carnivalesque, gross-out and also rapey set of scenarios leading to a disturbing climax, not dissimilar to the controversial pilot episode of Black Mirror.)

- Paul Jennings uses fat kids as the bully character. This was very common in the 1980s. Fat boys were either enemies or pathetic. In modern stories, the fat boy is still sidekick to the main character Every Boy, though he’s often a nicer person than everyone else. This isn’t really an inversion until fat boys get to be the stars of their own stories, which aren’t about the experience of being fat. In The Cabbage Patch Wars, two dads with beer bellies engage in a weight loss competition, in an era before Biggest Loser was a thing.

- There’s a disproportionate number of redheaded kids in Paul Jennings stories. Like most children’s writers, he tends to use red hair as a ‘stand out’ attribute — by giving a kid red hair he is saying ‘keep an eye on this character’. Jennings uses a red headed kid for the bully in “A Good Tip For Ghosts” but the red headed kid is a main character in “Ice Maiden”, and despite hating red hair himself, he ends up falling in love with a red headed girl. Also, his red hair saves his life. So Jennings is trying to tell us that red hair isn’t so bad in one story, yet uses red hair however he sees fit in other stories.

- If an evil person is introduced, and that evil person is mistreating others you can bet Paul Jennings will exact punishment on that character, even if it requires a final section of the story to do just that. In other words, he ties off every other strand in the story, and it might end there, but then he goes back in for the punishment. These stories are famous for being about anarchy and fun, but they are conservative in their values.

- Look closely at these stories and you’ll find they are basically very conservative, and sometimes clearly didactic. “The Busker” is about how you can’t buy friendship. Yet in “Spaghetti Pig-out”, the main character buys friends with a magical device. So stories contradict each other in their moralism.

- The idea that bad people do bad things and also get away with it is not part of the Paul Jennings setting, although it is part of real life.

- Stories which revolve around a reordering of hierarchy are so common, not just in the Paul Jennings oeuvre, that we rarely stop to think about how to completely subvert the hierarchy itself. As Matt Bird says about Battle sequences in general, at first the main character is socially challenged (usually via humiliation). This is absolutely true of Paul Jennings stories. We are lately starting to see a pushback on this fundamental idea. Australian feminist philosopher Kate Manne says it best in her critique of Jordan Peterson’s viral “12 Rules For Life”:

Critiquing these hierarchical structures and finding, when possible, a way to live outside of them in more co-operative ways are obvious alternatives for human beings about which Peterson says little.

- I have exactly the same thing to say about Paul Jennings, who has nothing to say about how to live outside hierarchies, or about dismantling the hierarchies altogether. Instead, story after story fulfils the wish to move from underdog to king pin, often by dumb luck and with magical help rather than by achieving any special insight.

WRITING STYLE

- The writing style is conversational rather than literary.

- A strong 1980s, 1990s Australian voice comes through, in emulation of the ‘True, blue Aussie’ which certain politicians like to emulate, even today. This voice is in itself a kind of fictional caricature, which isn’t to say that certain people don’t make full use of it as a character gag. Mick Gould who stars in Australia’s 2019 Married At First Sight also uses this distinctly Australian larrikin persona for enduring comic value and audience empathy, so it hasn’t gone away. This voice is full of idiomatic expressions, mixed metaphors for comic effect, telling it like it is, positioning oneself as hapless and unpretentious, and making use of borderline inappropriate language (insofar as a children’s book will allow, hence “Birdscrap”, which can be explained away as “Bird Scrap” rather than its real meaning of “Birds’ Crap”).

- Emotions are described matter-of-factly in a single sentence e.g. ‘I felt embarrassed,’ ‘I felt silly‘.

HUMOUR

- A useful taxonomy of humour in children’s stories. Paul Jennings makes heavy use of slapstick.

- Physiological reactions are comical — they could easily happen in a Cartoon Network show. Knees knocking, obvious blushing, teeth chattering.

- Titles such as “Birdscrap” are word play and also taboo.

- Readers take delight in upending authority. This kind of carnivalesque humour is utilised across many picture books, which makes these hi-lo readers a natural progression for young readers. This type of humour is still very popular here in Australian children’s publishing, with the Treehouse creators saying that children crave ‘irreverent’ humour. Irreverent is another way of saying the same thing. Terry Denton and Andy Griffiths also talk about the importance of ‘anarchy‘, and this applies equally to Paul Jennings, who has surely been influential on their work.

- Humour has been classified into ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. Men and boys are more likely to use ‘negative’ humour — to belittle, to humiliate etc. Paul Jennings stories are far more likely to belittle and humiliate, with a few exceptions e.g. “The Mouth Organ” (in which, no coincidence, he chooses a girl for his narrator).

- Jennings makes use of gross-out elements. (A sea of bird poo, a creature picking a boy’s nose for him, being stuck in a skip full of rubbish, a dug up skeleton etc.)

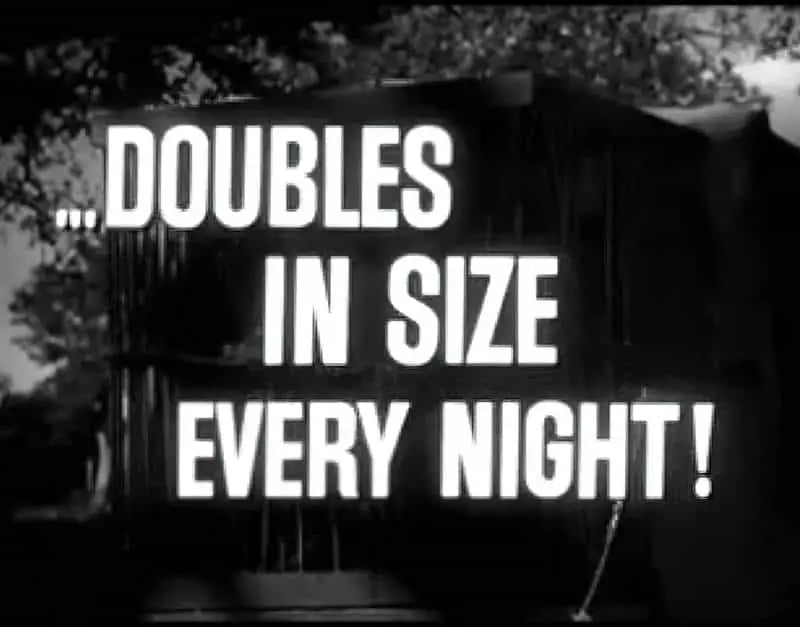

- In tall story tradition Jennings plays around with scale and size. (This is also a feature of myths e.g. Greek myth.) For example, a shack is surrounded by a sea of seagull poo, a tooth grows bigger than the man to whom it belongs. Jennings understands that by playing around with scale, he creates resonant imagery for the reader. Other examples: ‘A pumpkin so big it took four men to lift it’, ‘peas as big as golf balls’, ‘beans were as long as your arm’, so many flies they black out the sun. Extreme stench is utilised in several different stories. In the humour taxonomy, this is gross-out overlaid with hyperbole.

- Related to big things as small, small things as big, creatures and things operate in the way we don’t expect. Oftentimes, it’s a simple inversion. For instance, in Sucked In, we are led to expect that a cat is about to eat the escaped appendix. The illustration shows a massive cat (so massive the cat is partly off the page) with the much smaller appendix in a vulnerable position beneath the cat. But turn the page and the appendix eats the cat. This is ‘man bites dog’ humour, funny because it subverts expectations.

- Bad smells are a common feature of Paul Jennings stories, especially if they overwhelm an entire town. (“Greensleeves” is one example)

- Humiliation of the main character is often a large component of the humour. We empathise with the main character because he is in an underdog embarrassing situation. He comes up trumps at the end, not because of his own superpowers coming to the fore, but because the gods are smiling upon him. He remains a low-mimetic hero (Northrop Frye’s classification).

- Disembodied body parts are commonly utilised throughout Paul Jennings stories. False teeth are the star of several different narratives (“A Good Tip For Ghosts, The Cabbage Patch War). In Sucked In, an appendix in a jar is the star. We have a dismembered finger in “On The Bottom”.

- Nudity is both funny and humiliating (cringe humour). Bums especially so (“On The Bottom”). Mention of exposed genitalia would be considered inappropriate for this age group, but we do have an entire story about a pissing contest.

HOW DOES JENNINGS TWIST HIS TALES?

The big selling point of a Paul Jennings collection is the twist-in-the-tale. You’ll find this promise on the advertising copy. This seems to be what impresses readers the most.

Some of the stories contain two twists: One in the Level 0 story, another in the Level 1, meta story.

Some of the ‘twists’ only work on a child audience. The sophisticated adult reader sees them a mile out. Paul Jennings does not attempt a dual audience, and that largely explains his success: His stories for kids are really for kids. On the other hand, sometimes the reward is in knowing exactly what’s coming. There’s a visceral delight in that.

Christopher Vogler has pointed out that ‘twist endings’ are most often sardonic, bitter, wry and I would add ‘vengeful’. It is much more difficult to write a twist ending that does not invoke these negative (but satisfying) emotions in us. A rare exception is the famous short story by O. Henry, “The Gift of the Magi”. Paul Jennings doesn’t do ‘kind’ twist endings. (Twist endings which say something lovely about humankind are very hard to pull off.)

Another twist Paul Jennings does NOT do: The scary supernatural creature turns out to be no such thing. Once Jennings creates his scary opposition, that opposition is real within the setting. The ‘and it wasn’t really real’ twist is not satisfying. It’s a close cousin of ‘And then I woke up and it was all a dream‘.

- Jennings reveals that an authority figure has the same desires as the kids, proving himself not so high and mighty after all. (“Pink Bow Tie”). This is a carnivalesque trick because it upends the adult-child hierarchy.

- A storyteller spins a yarn which the young viewpoint character fully believes. The twist is that the storyteller is full of yarns, and the existence of the second yarn disproves the veracity of the main yarn. (“One Shot Toothpaste”.) This is a tall tale trick.

- A character with a certain strong character trait (e.g. fearlessness) goes through an experience which serves to invert that trait (e.g. he is now scared of not scary things) (“Inside Out”). This draws on the mechanism of irony. The reader expects a character arc to be: Child learns to conquer his fears.

- A mysterious storyteller who tells his tale in third person is revealed to have been telling the story about himself all along. (“The Busker”)

- A fantastic tale is not fantasy at all, then leaves off with a detail or explanation that suggests the fantastic tale might be fantastic, or it might not. (“Souperman”)

- A situation is resolved, seemingly forever, but then it is revealed in the final paragraph that this is a repeating story and is likely to happen again. Paul Jennings gets a lot of mileage out of this one. (“One Shot Toothpaste”, “The Gum Leaf War”, “Come Back Gizmo”, Sucked In) Often, the first and main story happens to a boy, then the next (untold) story is about to happen to a girl. DreamWorks did the same in its movie adaptation of Boss Baby. (They probably think this counts as gender diversity.)

- A Holy Grail object of desire is revealed to have been right there, staring them in the face all along. (“Birdscrap”)

- A villain opponent is revealed to be more of an ally, and ends up helping the young character get with they want. Sometimes this is a ghost, who seems scary at first but is revealed to be kind. (“Birdscrap”, “Skeleton On The Dunny”)

- An opponent with a formidable reputation turns out to be much less scary once met face to face (“A Good Tip For Ghosts”).

- An opponent for the child viewpoint character turns out to be an ally for another character, because everyone’s needs are different. (“Snookle”)

- A weird situation is revealed to be supernatural in origin, and has a classic horror story resolution (“Without a shirt”)

- A smart trickster outwits an evil trickster (“Box Strap Flyer”, The Paw Thing)

- The reader thinks the worst that could happen has already happened, but then something outrageous and unimaginable is about to happen next. This scene may be so risqué it is left entirely for the reader to imagine. (“Lucky Lips”). This is a popular type of humour shared by many comedians, e.g. by Oliver Jeffers in his picture book Stuck.

- An object which is terrible turns out to have a silver lining for the main character. (“Cow Dung Custard”)

- A character accomplishes something using a certain trick which is not revealed to the reader until the final sentence. (“Wunderpants”) This is how heist stories work. The character makes plans behind the scenes. The character has a realisation midway through the story and this is not related to the audience.

- Rather than a twist, Jennings sometimes uses the inverse: Everything in the story leads to an expected and satisfying payoff… or rather, payback. In “Birdscrap”, the story ends at the point where the highly unempathetic opponent is about to land headfirst in manure. In “Spaghetti Pig-out” we wait for the magic remote to work against the bullies.

- After a psychological horror sequence, a character realises what they need to do to get themselves out of a horrible situation, so they do it and it works via off-the-page magic. (“The Velvet Throne”)

- To emphasise his twist, Jennings sometimes gives us the ‘twist’, swiftly followed by the answer to a mystery he has set up. This feels extra satisfying, and can make up for a less-than-stellar twist. He does this in The Cabbage Patch War. We learn in quick succession that the person accused of stealing the cabbage is not the real thief. Then we learn that one character won a weightloss competition by removing his false teeth.

- A character is killed, then brought back to life with hitherto unseen magic (“Frozen Stiff”).

- Sometimes a main character works something out before the reader does, then sets about to fix a situation. (Russell works out his mean teacher’s smile has been stolen before we do in “Cracking Up”, “Know All”.)

THE ILLUSTRATORS FOR PAUL JENNINGS

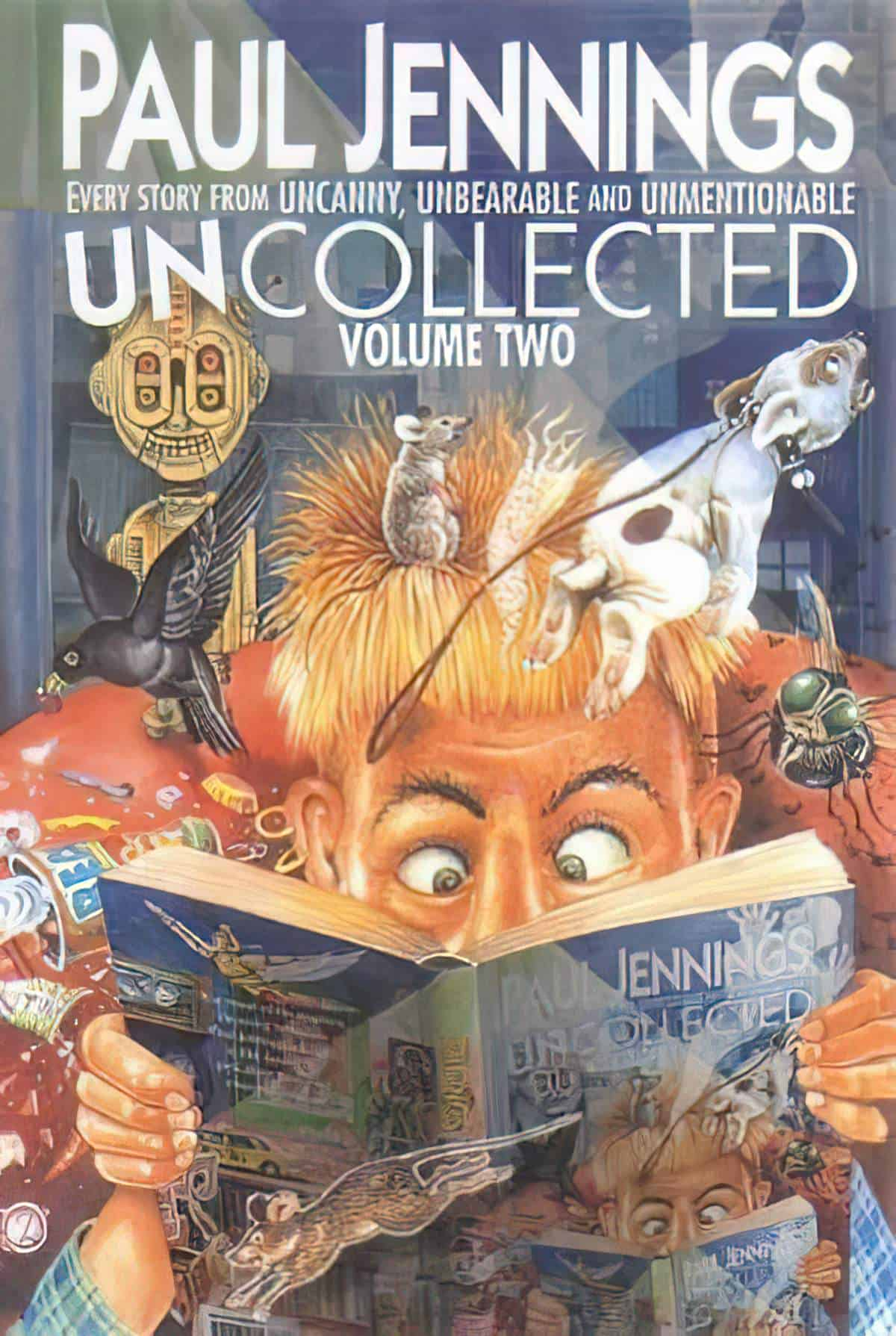

More than Goosebumps, the stories of Paul Jennings (and Morris Gleitzman) were influential for Australian and New Zealand kids of the 1980s.

- EPS template

- PSD file

- Affinity Photo file

- PNG overlays:

Who really created the artwork for Paul Jennings children’s books in the 1980s? Many illustrators have collaborated with Paul Jennings over the years.

BOB LEA

- Rascal at the Show

- Rascal and the Cheese

- Rascale and Little Flora

- Rascal and the Hot Air Balloon

- etc.

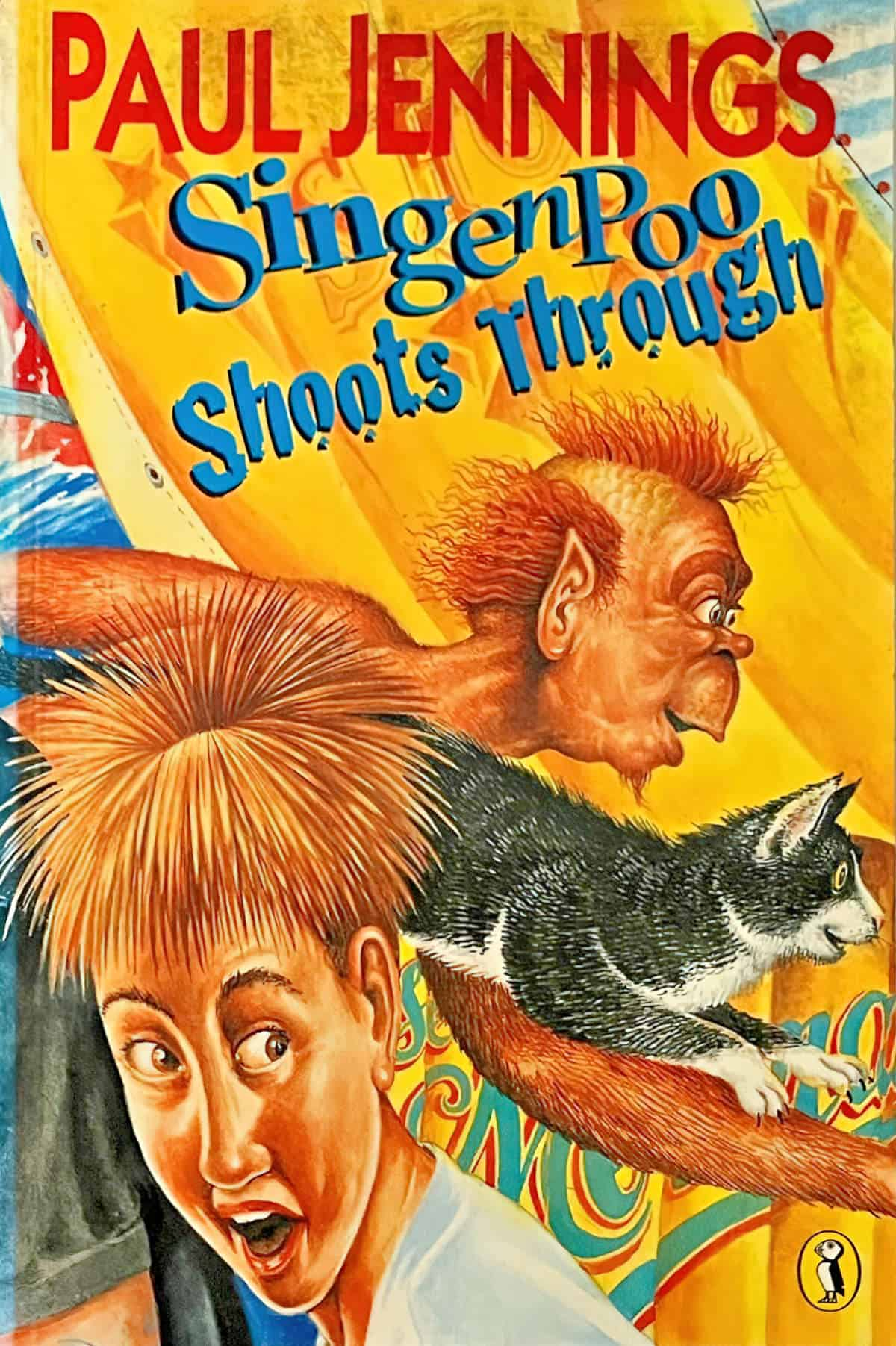

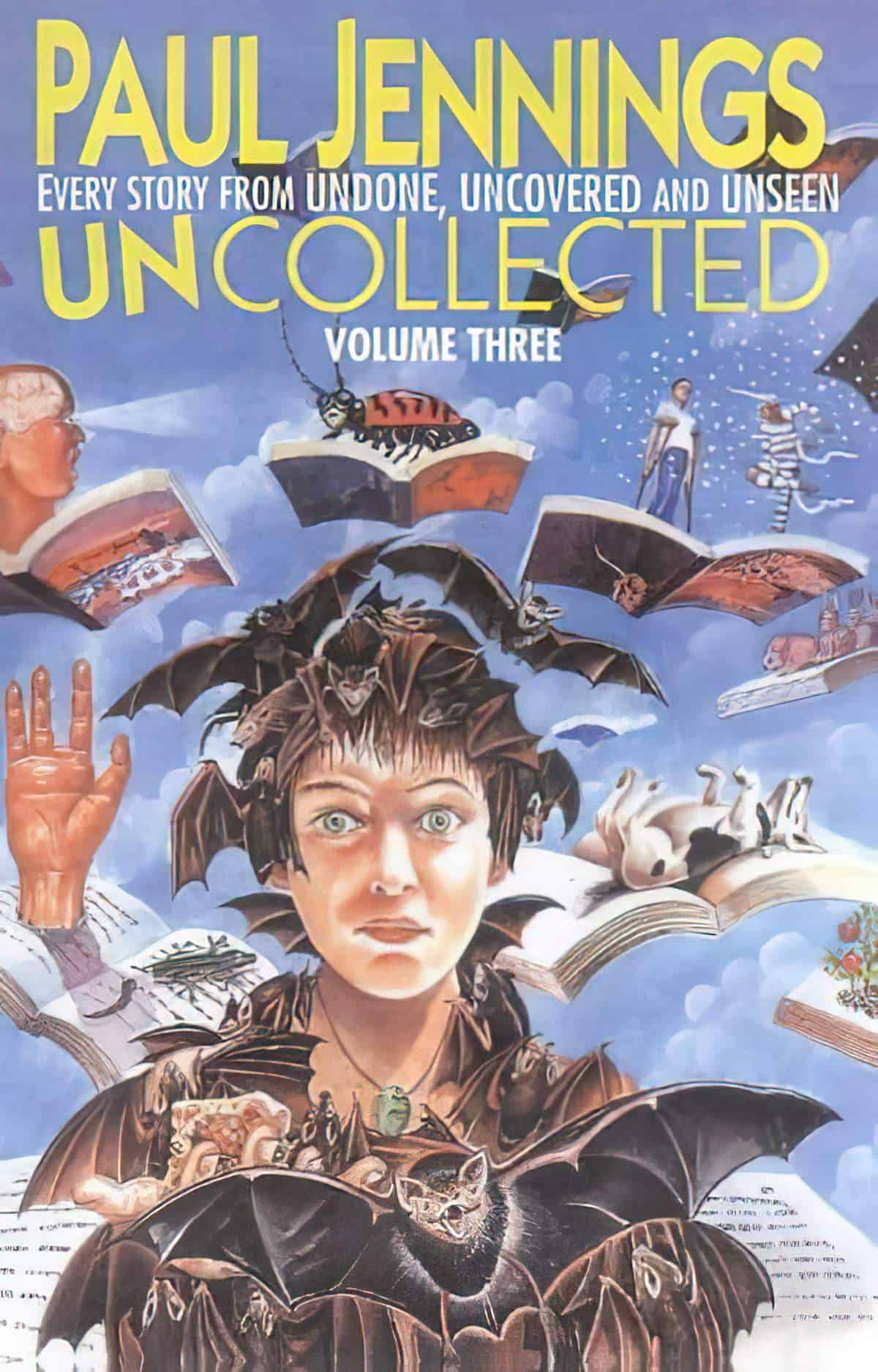

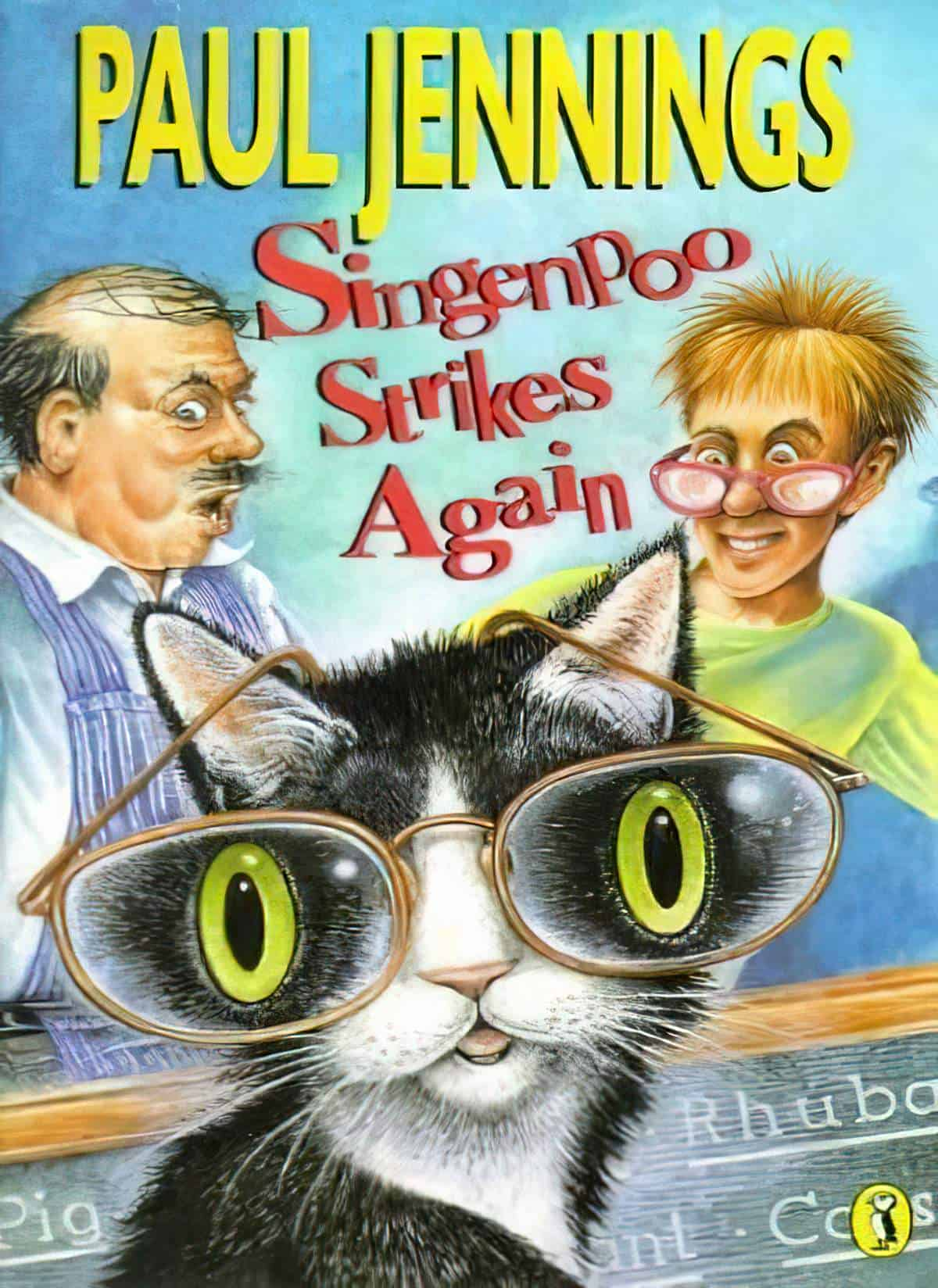

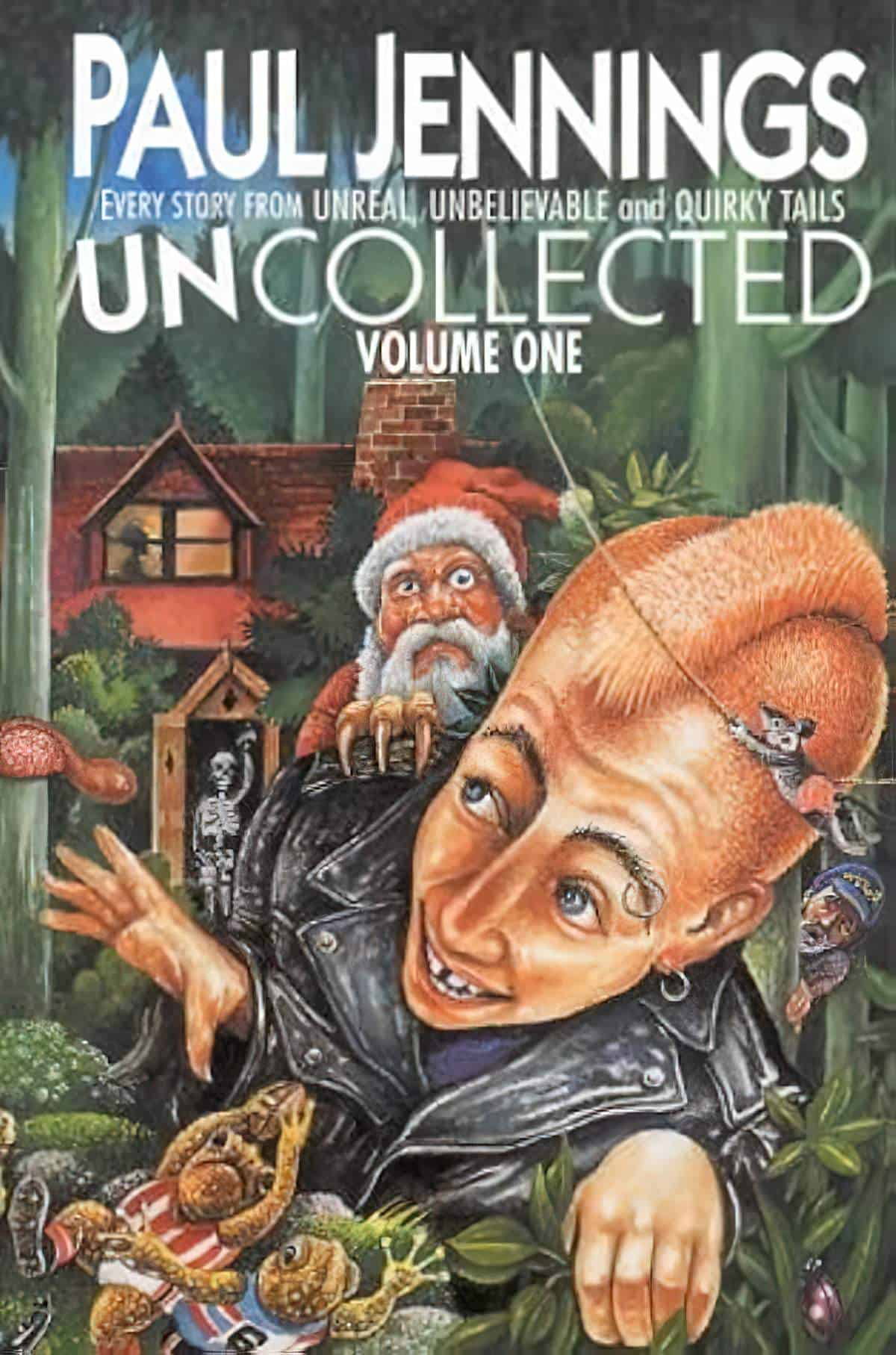

Keith McEwan

- The Paw Thing

- The Gizmo

- Singenpoo Shoots Through

- Singonpoo’s Secret Weapon

- Unreal

- Unbelievable

- Undone

- Uncovered

- Unseen

- etc.

Jeanette Rowe

- Teacher Eater

Peter Gouldthorpe

- Grandad’s Gifts

Terry Denton

- Spooner or Later

- Sucked In

- Spit It Out

- The Treehouse books

Glen Lumsden

- Round the Twist Graphic Novel

David De Vries

- Round the Twist Graphic Novel

Jane Tanner

- The Fisherman and the Theefyspray

TED GREENWOOD

- Duck for Cover

Craig Smith

- The Cabbage Patch Curse

- The Cabbage Patch Pong

- The Cabbage Patch War

- The Cabbage Patch Fib