Nomadland is a 2020 film directed by Chloé Zhao, starring Frances McDormand, David Strathairn and real people engaged as temporary actors, playing a version of themselves.

If you’ve seen American Honey directed by Andrea Arnold, you’ll have seen this done before, and done very well. In these stories, the actors are authentically from the environment, but their narratives are fictional. For instance, the character Swankie is a real nomad called Swankie, who has been living the nomadic life for over a decade. But in the film, fictionalised Swankie has terminal lung cancer which has spread to the brain. This is not the story of the real Swankie, who is alive and well.

- Frances McDormand as Fern

- David Strathairn as Dave

- Charlene Swankie as Swankie

- Gay DeForest as Gay

- Patricia Grier as Patty

- Linda May as Linda

- Angela Reyes as Angela

- Carl R. Hughes as Carl

- Douglas G. Soul as Doug

(Actors ‘playing themselves’ were paid to be in the movie, though some of them did not expect to be at the time.)

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

PARATEXT OF “NOMADLAND”

After losing everything in the Great Recession, a woman embarks on a journey through the American West, living as a van-dwelling modern-day nomad.

Marketing copy

The film is based on Jessica Bruder’s award-winning ‘gonzo investigation of transient American seniors who follow seasonal employment while living out of their vans‘.

The inspiration for Chloé Zhao’s 2020 Golden Lion award-winning film starring Frances McDormand.

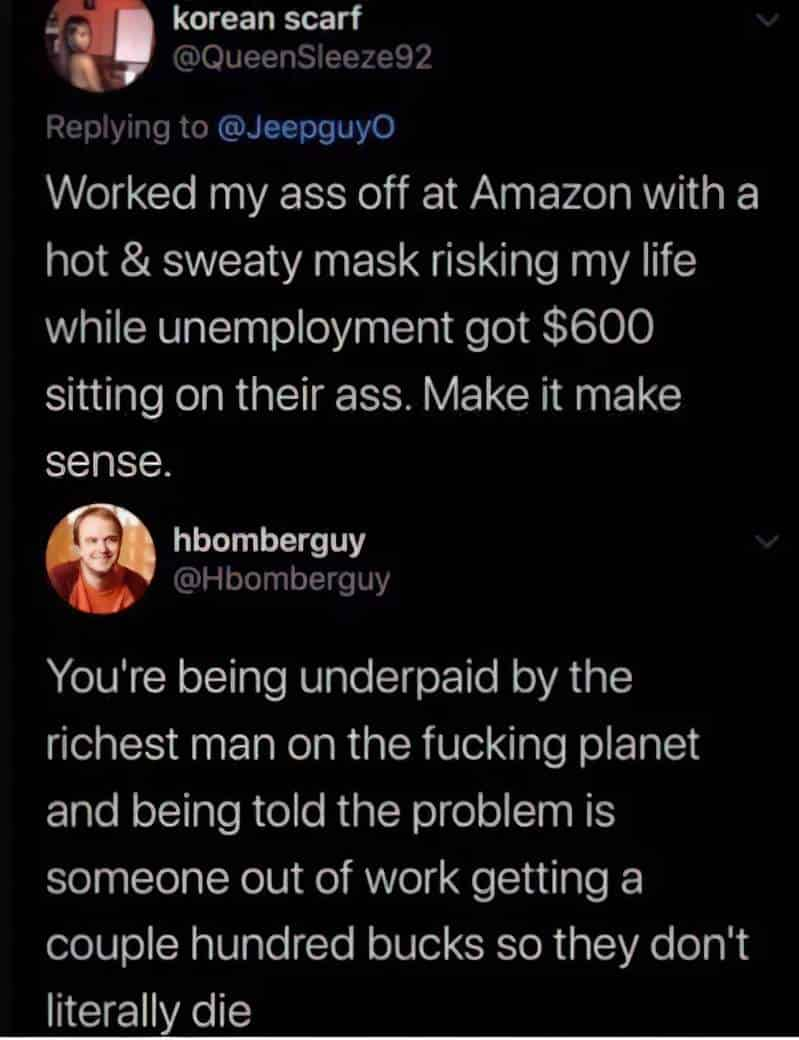

From the beet fields of North Dakota to the campgrounds of California to Amazon’s CamperForce program in Texas, employers have discovered a new, low-cost labor pool, made up largely of transient older adults. These invisible casualties of the Great Recession have taken to the road by the tens of thousands in RVs and modified vans, forming a growing community of nomads.

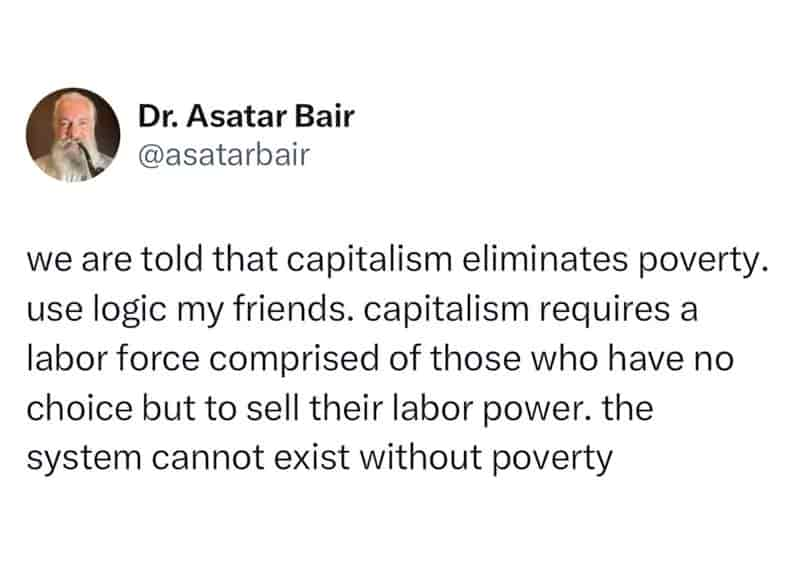

Nomadland tells a revelatory tale of the dark underbelly of the American economy—one which foreshadows the precarious future that may await many more of us. At the same time, it celebrates the exceptional resilience and creativity of these Americans who have given up ordinary rootedness to survive, but have not given up hope.

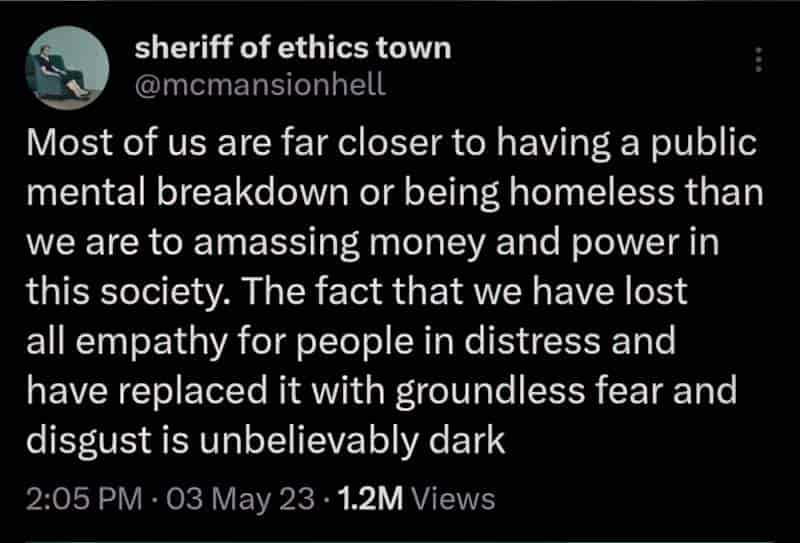

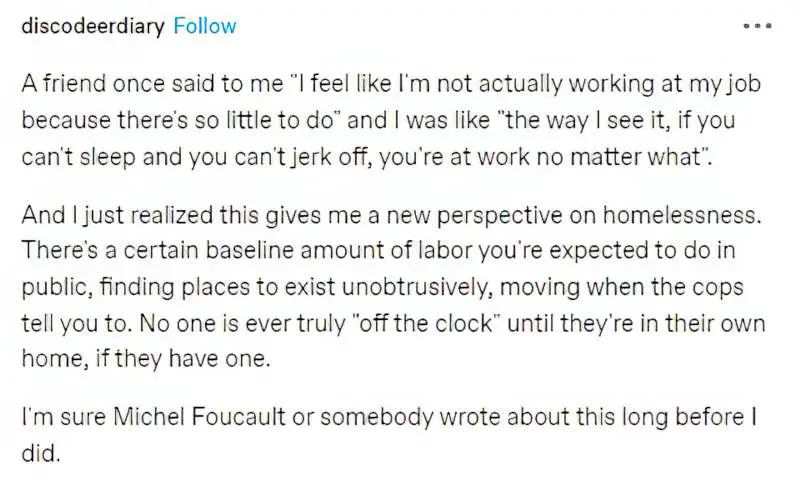

AUDIENCE REACTIONS TO STORIES ABOUT HOMELESSNESS

Nomadland concerns the societal issue of enforced homelessness, so I’ll state my position on that topic up front. A strange thing happens whenever someone critiques an economic system which divides its citizens so starkly, between homeowners and non-homeowners: Some people (themselves comfortably housed) fail to draw the distinction between a critique of the system which created this bifurcation, and a critique of the temporary dwellings themselves. Fiction teaches us all to conflate character with housing. How many stories can you think of in which audiences are encouraged, nay pushed, towards considering a character’s home an outworking of themselves? All of them, you say? Like, every single one, maybe? A chaotic desk for a chaotic mind, a wall of glass for a cold, distant relationship, a house full of antiques for a character stuck in the past… the list goes on.

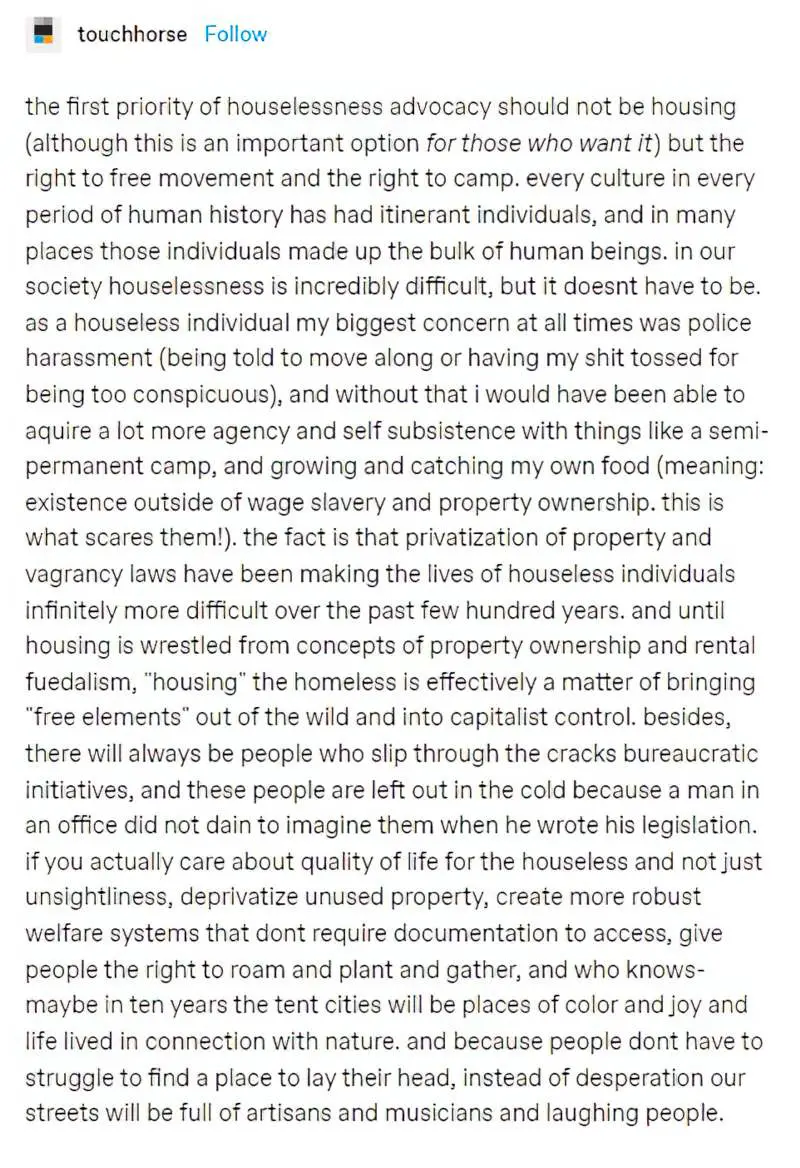

Rarely do we find a story which asks us to think hard about whether housing situation really does reflect character (and morality). Nomadland is a story which unlinks character and housing, because this is a story of realism: the ultimate realism, straddling fiction and documentary. The houses people live in is far more an outworking of socioeconomics, not of personality, not of morality.

An irritating argument will likely kick off around a story such as Nomadland: The main character, Fern, experiences a psychological arc from imperilled displacement to embracing freedom. In audience members, I’ve noticed this arc elicits two incompatible interpretations:

- Homelessness is terrible, but homeless people themselves have dignity, courage and strength and are sometimes able to make the best of a tenuous situation.

- Homelessness isn’t so bad, actually. In fact, it’s a type of freedom. I was actually quite jealous of Fern by the end.

Some call them “homeless.” The new nomads reject that label. Equipped with both shelter and transportation, they’ve adopted a new word. They refer to themselves, quite simply, as “houseless”.

[…]

The truth as I see it is that people can both struggle and remain upbeat simultaneously, through even the most soul-testing of challenges.

[…]

Sameer and LaVonne were not naive. They know that, in the eyes of the law, they are homeless. But who can live under the weight of that word? The term “homeless” has metastasized beyond its literal definition, becoming a terrible threat. It whispers: Exiles. The Fallen. The Other. Those Who Have Nothing Left. “Our society’s untouchables,” LaVonne suggested on her blog.

Jessica Bruder, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century

Daddy had been away for two long years, and now he was back again! Mummy smiled all day long, and the three children were happy too.

Soon Daddy and Mummy began to talk about where they were going to live. “We can’t live with Granny any more,” said Daddy. “We must have a home of our own.”

“A dear little house in the country!” said Mike, the eldest.

“Called Cherry Cottage,” said Belinda, who was next.

“And let’s keep cows,” said Ann, the youngest.

“We’ll try and find all you want,” said Daddy, and he laughed.

So they tried. They heard of cottages here and houses there, but oh dear, when they went to see them, they didn’t like them a bit!

“Well, whatever are we to do?” said Mummy. “We really can’t all live at Granny’s for the rest of our lives!”

Then they found one dear little cottage with roses growing all the way up the walls. It was set on a hill and had a lovely view.

“We’ll have this!” said Mummy. But the price was very high, and Daddy hadn’t enough money to buy it. So that was no good either.

They came away from the cottage feeling rather sad. “We shall never find a home,” said Mummy, and she looked so miserable that Daddy put his arm round her and gave her a hug.

“Don’t give up hope!” he said. “Why, you may find a home round the very next corner!”

“Things like that don’t happen, Daddy,” said Mummy, but she laughed.

“I wonder what’s round the next corner,” said Belinda. “It would be funny if Daddy’s words came true!”

“We’ll see what houses there are when we come to the next corner,” said Mike. So they all looked hard when they came to it.

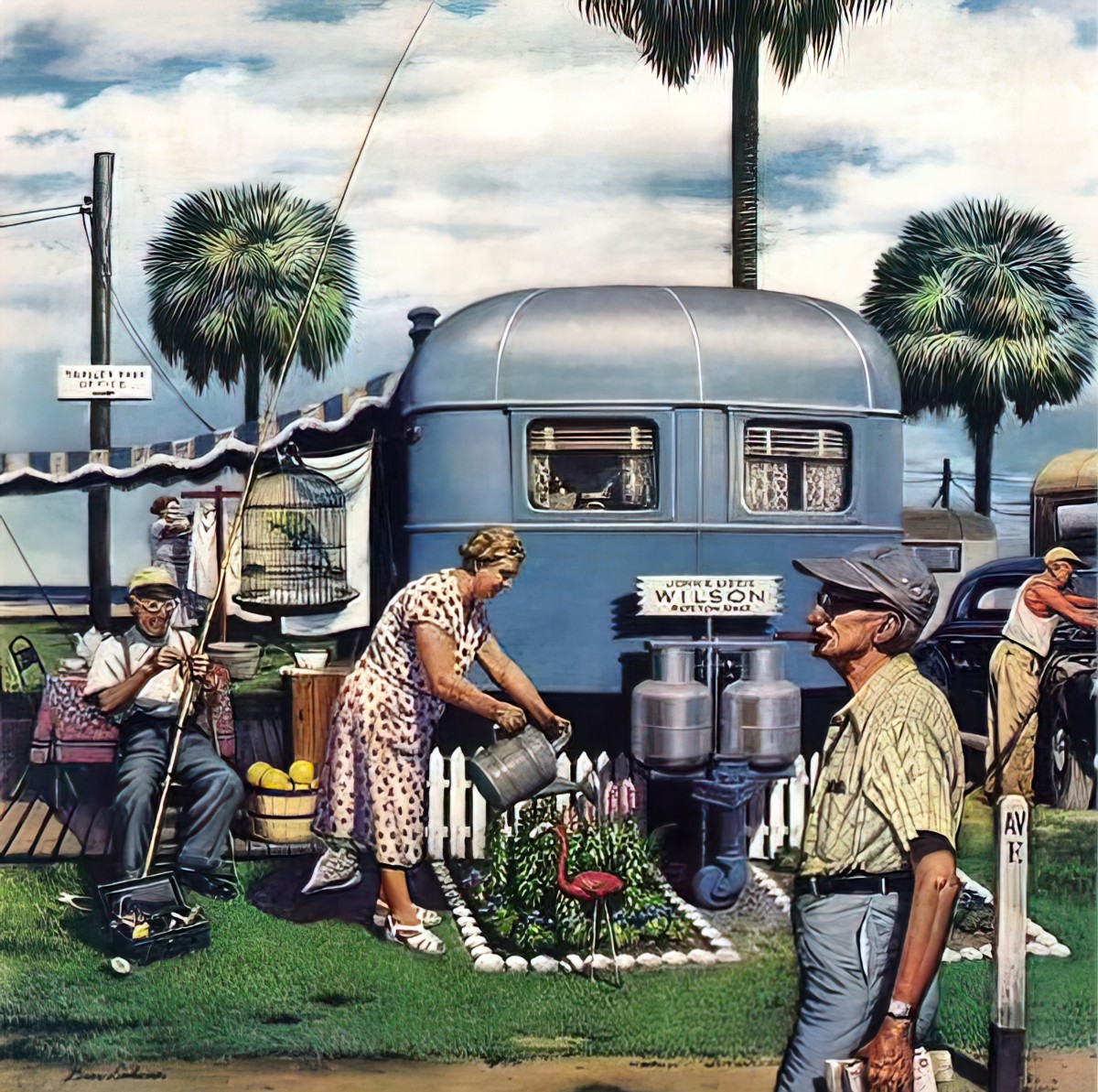

There were no houses to be seen at all—only two old caravans, set in the corner of the field!

The Caravan Family by Enid Blyton, 1945, opening page

FREEDOM IS A TROUBLESOME WORD

Here in Australia, Gruen is a comedy show which critiques advertising efforts here and across the globe. Season 13 Episode 9 is called “Selling Summer”. The panel discusses an unusual — but very timely — 2021 marketing decision on the part of BCF (a Boating, Camping and Fishing retail chain).

In this advertisement, a young couple miss out on buying a house because investors are snapping it up as an investment property. The real estate agent encourages this young couple to keep their spirits up. He rips off his suit to reveal a Steve Irwin costume. Next, he shows them that although they cannot compete in the suburban housing market, they can use their hard-earned deposit to buy camping gear instead. In the tradition of a typically Australian children’s picture book, this campaign makes heavy use of designated Australiana, but has a disturbing message for us all: These young people may not ever own their own home, but hey! At least they can enjoy two weeks of annual summer holiday inside their very own tent, complete with port-a-loo, which they’ll own freehold. Ergo, young people have nothing to complain about really. Shut the hell up about intergenerational wealth transfer.

Only one expert on the Gruen panel critiqued the late capitalist environment which gives rise to pseudo-happy advertisements like this. Despite being a safely housed Gen-Xer myself (at least, for now), this is the most depressing damn “fun thing” I’ve seen in my life.

Deduce for yourselves how I feel about Nomadland as a feelgood ode to the freedom of the road. “But she chose it! Fern’s is the ultimate dignity! Hell, I might even donate my own house to a worthy cause and go permanent freedom campin myself!”

No. No one does this by choice (except Chris McCandless, but he’s so unusual he had a movie made out of him. Also, this freedom killed him).

Nomadland is an excellent insight into the politics of homelessness. The story avoids black and white depictions, includes a wide variety of people from many different backgrounds and interrogates common assumptions.

In an outdoor store, Fern runs into a former student, who asks if she’s ‘homeless’ now. Fern rejects the word ‘homeless’. “Just house-less,” she says. “Not the same thing, right?” This marks a more general shift away from the word ‘homeless’ to ‘unhoused’, which, for now at least, is a description of circumstance without the negative connotations.

SETTING OF “NOMADLAND”

Setting is everything in this story.

PERIOD

For 63 years, from 1948 to 2011, Empire was a company town of the US Gypsum Corporation, a manufacturer of gypsum based construction sheetrock, and once had a population of more than 750 people. US Gypsum closed the mine and the town in 2011; the mine and town were bought in 2016 by the Empire Mining Company (EMC), a manufacturer of gypsum based agricultural and construction additives. […] The film is set in 2011 and 2012, and its script intentionally omits any reference to the 2016 re-opening of the town, ending the film’s story line apparently sometime before the 2016 re-opening.

Nomadland opens around Christmas. This is why Fern has been employed by Amazon, to deal with Christmas demand, we deduce. As soon as Christmas is over, Fern is out of a job. No one mentions Christmas. For those away from family, without material means, without a religious tradition, Christmas is a non-event.

On New Year’s Eve, Fern eats alone in her freezing cold van. The only (subtle) indication of high spirits: Fireworks popping off in the background.

DURATION

I’m not sure from watching that the story covers a single year. It may cover two or three? I’ve seen it three times and I haven’t noticed any concrete clues. Others may have watched more carefully for it, but I believe the imprecise time is a deliberate experience created by the director.

More importantly, audiences feel a story which comes full circle. Nomadland is an example of a circular-linear plot. (Linear because all road trip stories are, and circular because it begins and ends in the abandoned town of Empire.)

I’ll see you down the road.

Nomadland tagline, Bob Wells of Cheap RV Living

One big issue facing storytellers crafting a road trip journey (or any kind of Odyssean myth): fragmentation. Pretty much the only way to get around this is to have the main characters encounter minor characters time and again. See the epitome of this technique utilised in this story which is about finding a community, but while travelling.

The tagline reaches beyond the here and now, right into the afterlife. ‘Down the road’ refers to the afterlife for the character who came up with the phrase, having lost his son to suicide.

LOCATION

Various popular RV spots across the USA, e.g. the famous Quartzsite, Arizona (‘Rock Capital of the World’).

Although this story focuses on the demise of Empire, Nevada, ‘it’s based in reality — though it could pass as allegorical, with so many towns and cities across America suffering similar fates in the wake of the country’s post-industrial, post-GFC decline.

ABC

ARENA

When three main characters board a luxury RV for sale in a yard and imagine what it’d be like to own such a beauty, one of them suggests they drive it to Hawaii. They are joking, of course, since ‘there’s water between’. Swankie points out that they should avoid the East Coast because a vehicle of this magnitude would never find anywhere to park. Nomadland concerns the wide, open, vast spaces of the USA, which make you feel tiny simply to exist in that space.

MANMADE SPACES

Nomadland is a road trip story, so the road is of course vital. America’s vast network of highways changed all American lives forever.

Also, the characters in the story are a mixture of those there by circumstance and those there by choice (though even choice is a spectrum). The main character, Fern, is not there by choice. She drives a cheap, self-modified vehicle which will eventually break down. When she imagines herself driving the luxury RV, the story gives us a beautiful contrast between the haves and the have-nots.

There are other contrasts:

We see [Fern] employed first in an Amazon warehouse. It’s a cavernous hangar that rings with the endless beeping of barcode scanners, and which blights the surrounding Nevada desert like some kind of bleached alien monolith.

ABC

NATURAL SETTINGS

The cinematography of Nomadland is beautiful. It is so beautiful, in fact, audiences will want to inhabit the same spaces as Fern. We marvel at the sunsets and sunrises. Of course, Fern is must be up early to see that beauty because she works long hours.

Rocks. Highly symbolic.

I’m reminded of Annie Proulx, and I hope that’s not just because Charlene Swankie bears an uncanny resemblance to Annie Proulx the author.

Annie Proulx makes frequent symbolic use of rocks in her stories, and connects the landscape beautifully to character. Here’s just one example:

Atoms of this granite whirled in his body. Its stony, obdurate qualities passed up through the soil and into plant roots. Whenever he took potatoes from the heat-cracked bowl, his bones were hardened, his blood fortified. But Maureen, he knew, was shot through with some wild astral substance so hard and dense that granite powdered into dust beneath her blows.

Annie Proulx, “Bedrock“

The rock symbolism of Nomadland is there from the beginning. Empire Nevada was all about the gypsum based construction sheetrock. Dreadlocked nomads collect rocks to sell for subsistence living via small landscaping businesses. Swankie is an expert on the different types of rocks.

Somewhere near the mid-point of the film, Fern encounters Dave who is working as a tour guide at a site famous for its rocks with airholes in them. Fern leaves the group and wanders through the rock-scape. You just know this scene is highly symbolic, right?

For me, this tourist site resembles a miniature of a much larger landscape. Walking through, Fern looks gigantic. Storytellers frequently make use of the miniature in fiction. A gigantic Fern walking through a miniaturised landscape shows the audience that she now considers the big, wide landscape her home.

This wasn’t the case earlier in the film, when she’d rather put down roots in a terrifyingly cold town rather than travel south. She wanted to find a home and stay put. But now we see Fern encountering the same nomads on her journey. Although this is not a stationary troupe, she has found her people. She is no longer afraid of the wilderness. Later, when Fern revisits Empire and tells the guy storing the rest of her stuff to just get rid of it, this character arc is complete: She has turned the road (and the vast rocky landscape) into her home. She’ll never be back.

WEATHER

The narrative begins in the lead-up to Christmas, in a town where snow has settled. It is bitterly cold, and dangerous to the unhoused population.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

There may or may not be some technology which your plot will rely on. In some genres (especially science fiction) this technology will be central.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Writers are frequently advised to include conflict in every scene, though this advice can be used in a very annoying way: Constant bickering. Another annoying interpretation: Every single person a main character meets is an adversary. Sometimes for no reason. This turns me off. Constant conflict feels contrived, and is not pleasant to watch.

In Nomadland, conflict comes from the socio-political post GFC circumstance. In reality, adversity binds people together. So it makes perfect sense that Fern encounters people who are basically kind. When characters are kind to each other, especially when the degree of kindness is unexpected, this provokes pathos in an audience.

with the warm wind in their hair, but they can have fun in a golf cart.

When you’re old, you get personality.

Linda May

Note that even when people mean to be kind to each other, conflict will naturally arise. The character of Dave becomes the love opponent. Dave wants to settle down with Fern, whereas Fern is still emotionally connected to her dead husband and also, she doesn’t want to be tied down, emotionally, physically or otherwise. Fern herself has been shaped by individualism. She does not like to receive help from others. She is far more comfortable giving it (e.g. by walking around a campsite offering morning coffee). When Dave buys liquorice sticks for her she doesn’t want them. Note that Dave buys them because he wants her to quit smoking. Fern (correctly) interprets this as Dave’s wish to control.

In contrast, when Fern visits Dave in hospital after a bout of diverticulitis, she brings him a variety of heavily processed food of the sort she is able to afford, but also brings him a can of kippers. She has noticed kippers are his favourite. Is there any better signal of “I understand you” than a gesture which says, “I saw this and thought of you?”

Despite the will-they-or-won’t-they love plot, it is refreshing that Fern and Dave do not settle down together. Since Fern’s character arc is all about embracing freedom, to settle down with a man in a house (Dave’s son’s house) would feel wrong to an audience. Instead we must rest with the knowledge that Fern and Dave will be together, in a way, continuing to cross paths, but each on their individual journeys.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

This refers to the land which lives inside the main character.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

NEW BOOKS NETWORK Bonus Episode: “Nomadland”

One of the most-nominated films at this year’s Oscars is “Nomadland,” adapted from a book of the same name by journalist Jessica Bruder. “Nomadland” is about a 21st-century American phenomenon – the post-2008 increase in (mostly elderly) people who practice “vandwelling,” living in vans, trucks, or other mobile housing and traveling the country in search of seasonal jobs. This episode talks about the characteristics of this nomadic community, how they adhere to an anthropological definition of the term “nomad,” and nomadism in US history.

NEW BOOKS NETWORK Bonus Episode: “Nomadland”