Content note: This Little Red Riding Hood fractured fairytale contains off-the-page sexual violence.

Story by Lynley Stace and Elizabeth M. Phillips

Illustrations by Lynley Stace

There are a few things I’d like to get straight. Born to the largest man in our village, I was never what you’d call ‘little’. My name is Lotta. And my riding hood was not red.

It’s true that mama did not want me to walk alone through the forest that day.

She pointed from the kitchen window to a patch of sky. Snow looked imminent. “Lambert needs his foot seen to,” she said, “and the journey to Gran’s would take so long if you walked.”

I thought of a few things that might reassure my anxious mother: I would be taking the less populated route. Less chance of meeting against foul, so I reasoned. Besides, I had reached my full height that summer. With my long hair concealed beneath the hood of Papa’s riding-cape, anyone gazing on from a distance would assume from my heft that I was a male hunter, and therefore armed. My own concern was limited to my boots, and the way my toes had started pushing up against the leather.

Every small thing felt significant in those days. I sensed that if Mama should not grant my freedom that very morn, with Gran in urgent need of care and Mama herself occupied with horse business, then I would remain housebound until marriage, whenever that should be. I longed to leave our single-room cottage, to stretch my magnificent limbs every which way, to leap over creeks and swing on low-hanging branches, testing the endurance of my newly adult body.

“At least you won’t dawdle,” Mama said eventually, familiar with my long, swift stride. I grabbed the basket with glee and about knocked Mama off her feet with a bearhug. She would be sure to catch me up, she said, embarking upon horseback just as soon as the farrier had finished with our gelding.

“What were you doing waltzing though the woods unchaperoned?”

Wicker receptacles filled me with joy back then: Gingham-lined baskets were the enduring prop of picnics with friends and evening bonfires. The basket smelt of medicinal herbs. I’d made the bread rolls myself, proud of their rise. Mama had stewed the most tender portions of varmint and made a pasty, binding it inside layer upon layer of cloth so as not to attract wild predators. Mama had also baked a fruit cake which turned out dry as usual. “But Gran could moisten it sufficiently with a few dregs of wine.”

“I’m to take the wine? Really, Mama?” I never did enjoy the taste of toddy and Mama refused to drink alone. And she was always alone now that Papa had gone. I thought Mama would always keep his pretty bottle on our mantle as a remembrance.

“That wine might be the spoiling kind. In any case, Gran can keep the vessel as a vase.”

That’s when I decided to collect a posy of flowers along my journey. In fact, it may have been Mama’s idea.

“Why did you leave the path? Were you really just picking flowers?”

“You were wearing tight jodhpurs. The silhouette of a womanly figure is sure to get them going. Surely you were trying to attract attention.”

I’d been wearing Papa’s leather riding-cape since autumn. I loved every scuffed inch of it. And when I wrapped his scrim net scarf around my head I could enjoy his lingering scent. I was terrified a shower of rain would wash Papa’s smell clean away. I would have to beat the snowfall. And if I didn’t beat the snowfall, I’d have to beat the melt. I remember kissing Mama goodbye and striding out the door, just as Papa would have done. His riding-cape billowed as I rounded the corner at the foot of our property and for a moment I felt as large and powerful as he had been.

I wasn’t as wary as I’d promised I’d be, more intent on scanning the ground for those tiny blue flowers that grow throughout winter despite the frost — the ones with long green leaves, which look like comets streaking behind them. I picked the most perfect specimens for a posy, thinking all the time about my grandmother and how she, too, always managed to delight in the small things. Despite her ailment, I was sure she’d be grateful for flowers.

The woodland was crisp and still, punctured occasionally by an unidentified creature scrabbling among the undergrowth. I strode along the most oft-trod path. I have always enjoyed any opportunity to crane my neck upwards, and I did so now, marvelling at the height of the ash trees. As my boots felt tighter and tighter, I focused on the steady crunch of my footsteps. I had not yet lost my childhood sense of wonder and mimicry. I saw my own breath puff and dissipate in the chill air, so found a short stick about the size of a pipe. How manly and powerful I would look from a distance, with a pipe between my teeth! I imagined I could smell Papa’s tobacco.

“Do you have a father? What about boyfriends? Have you ever known a man?”

I could definitely smell tobacco. Not the inoffensive, floating-past kind, but the heavy, acrid kind that clings to your lungs. I’d smelt that somewhere before, but not on Papa.

I stood still for a moment, scanning the forest all around. There was nothing but darkness in there.

So I continued on, quickening my pace. I soon reached a clearing. The tobacco smell intermingled with the aroma of sawdust. These logs had not fallen; they had been felled. I sat on a stump for a few moments, heart quickened, inexplicably frightened by the solitude. I told myself that I was simply on the recent trail of a friendly huntsman, or perhaps even a merry family collecting kindling before the snowfall. On reflection, it was the silence that unsettled me. I heard no footsteps, no childlike laughter, no felling of trees.

“Why would he have waited? Why not pounce upon you in the solitude of the clearing?”

Youthful fancies ran away on me. I remembered tales of wild beasts — of witches and werewolves — recounted around campfires by village elders. Those tales were certainly exaggerated for the frisson, or to frighten us into blind obedience.

A movement caught my eye. It might have been a black deer, or else my imagination. Oh, but another one. Closer this time, I was certain. I had made it through the felled clearing now, and reluctantly re-entered the dark woods on the other side. I could no longer see any sky. I started to wish for the snowfall, which might at least lighten the landscape.

Then I remembered about wolves, and the hunter who had returned with a pelt just three months prior, and this after swearing they’d been hounded out of the area. If I was now caught on the scent-draught of a wolf, she might be stalking me from any direction. There may even be a pack of them. That’s when I started to run.

Above the sound of my own boots pounding against peat, I listened in vain for Mama, who had promised to join me on horseback. I had traversed this very wood many a time, but never alone. The trees looked so different now. Every slender branch, graceful and delicate just moments ao, now resembled the muzzle of some leaping predator, ready to sink its teeth into my ample flesh.

Faster and faster I ran. I considered ditching the heavy wicker basket, thud-thud-thudding against one thigh. Perhaps my pack of stalkers would make do with the stew and I would live another day.

And then, at last, with my chest cavity burning, the path widened and the trees thinned out. I had reached the edge of the terrible, wicked wood I’d been warned about since birth. Outside the dark of the forest, I found it had been snowing for some time.

Grandma’s rear field, even with the cherry morello naked for winter, had never looked so inviting. I considered sprinting across the white, propelling myself over the picket fence, and bursting in through Gran’s back door. But I didn’t. I needed to catch my breath. I wanted to show Gran that I had walked calmly through the forest alone, and could be trusted with any sort of adult responsibility. I would enquire after her health, peck her on the cheek, and insist on completing the day’s chores. In my calmer state, I noticed the lack of shimmer above Gran’s chimney. Her hearth would need attention. I decided to collect an armful of kindling before going inside.

Again, the smell of a pipe, both familiar and strange.

“Little Lotta,” he said, emerging from behind the woodshed. I could not tell you his name these days, or if I ever knew it. He had delivered a load of kindling for Gran. He’d been a frequent visitor to our own cottage, on the same business. I’d ofttimes seen him emerge from the village tavern and once, soon after Papa had gone, he insisted on walking me home from church. My mother followed close behind, and I own that I enjoyed the bulk of him ambling along beside me — a reminder that there are, indeed, marriageable men in the world who match me in height and exceed me in girth. He was the only man who could call me ‘Little’ without irony.

“You say you weren’t scared at first, that you’d spoken to him — many times before — that he’d even been to your house. Misunderstandings happen. Perhaps you gave him the wrong idea…”

He said he’d spied me, running through the woods. He told me about the huntsman and the wolf pelt, though I’d heard the story already. He embellished the details somewhat, and I laughed at his hyperbolic ferocity.

“Did you flirt with him? After all, do you not find the athletic build of a woodcutter attractive?”

But he wasn’t sharing any joke. “You should be careful,” he said, lowering his voice despite our solitude. “You might wear the riding hood of a man, and that military weave as camouflage, but you can never disguise your womanly opulence.”

I wished now for a smaller woodcutter, and one without an axe.

He stepped forward, lifted one flap of my basket, let it fall. He swung the splitting axe before him, between us, impressing upon me his danger and skill.

The axe dropped; his hand caught my wrist.

I’d always felt strong, but until that moment I did not know the meaning of brute strength.

I watch as the axe lies helpless against the ground.

After a while I close my eyes.

I have dropped the basket of goodies, and I know the bottle of wine has fractured, because a trickle of brownish-red stains the pure white snow.

Footsteps retreat.

Snowflakes melt on my face. I think only of the snow, and how it will cover his tracks. How if his tracks can disappear, and eventually the snow, perhaps I can imagine that he, too, has evaporated into the ether.

“Did you scream or say ‘no’? Did you offer any resistance? You say this happened right outside your grandmother’s cottage. You say she was in bed, right inside the cottage. So why did she not come to your aid? You must understand, it’s your word against his.”

“Lotta? Oh, Lotta!” Mother appeared above me. Thinking of nothing at all, I had not heard her approach.

I remember sitting wedged between Mama and Gran in front of a blazing fire. Gran had been ill and sleeping, though I saw a healthy fury that day, behind her wolflike eyes.

“I should have listened to those terrible tales. I shouldn’t ever be alone.”

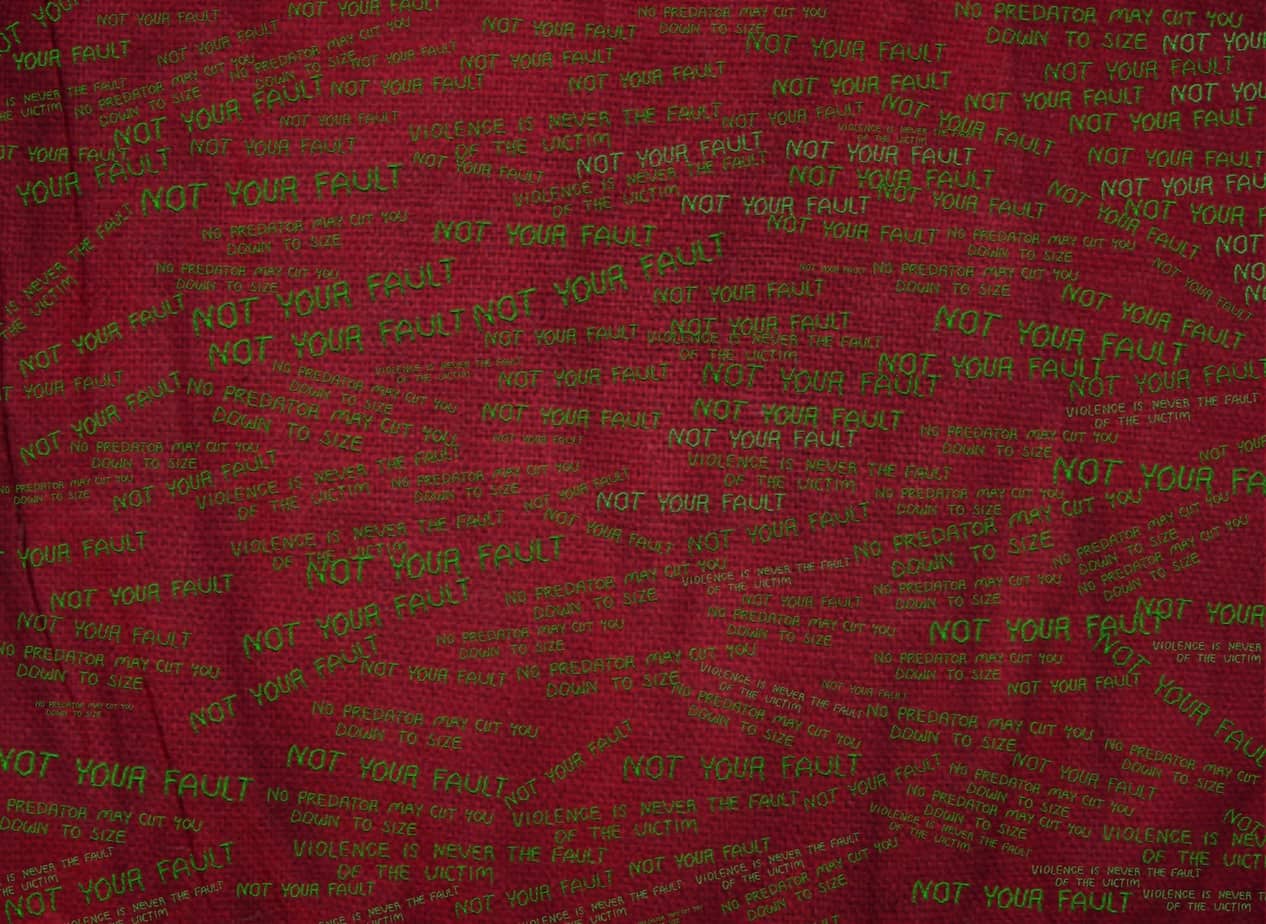

That was the winter Gran grew worse. As her eyesight weakened, knobbled fingers sewed for me a double-milled scarlet chaperon.

Mama helped with the embroidery.

Perhaps you’ve seen me, during decades since passed, traversing the woods without fear. The forest is dark, and I am a red blaze against it, and I will not become invisible. All the better to see me with, my dear.

I am not little. No woodcutter, no malicious predator — one at all — can cut me down to size. These days I wear a riding hood of the brightest scarlet, sewed for me by my grandmother as she convalesced in her bed.

When co-writer Liz first saw my illustrations she asked, “Why is the character of Lotta drawn on crumpled paper?” I figure she wouldn’t be the only one to wonder that. My answer is that because Lotta has all these rules placed upon her daily movements, she is highly restricted and therefore not fully integrated (or accepted) into the story environment. But that changes. Her response to trauma is to push herself fully into the world rather than retreating from it, which is partly what assault (and threat of it) is designed to do. In the final image, Lotta is fully integrated into the background.

I did a lot of research before co-creating this story. For more on the history and influence of Little Red Riding Hood see my collected notes in this post. I came to believe all versions of Little Red Riding Hood are about women and girls and predators outside the home. The bowdlerised versions for modern kids are ostensibly not about that, but Little Red Riding Hood changed once the Grimms got hold of it and promoted a patriarchal version. It was previously a ‘spinning tale’, created by women, told among women.

For as long as women have been sewing, they’ve been using embroidery to tell their own stories—often in societies that refuse to hear them otherwise.

Mark My Words: The Subversive History of Women Using Thread as Ink by Rosalind Jana