I’ve previously taken a close look at wolves in literature, specifically in children’s stories. Werewolves are a separate archetype from wolves and play a different storytelling role. In folklore and fairytale, werewolves are lunar figures which stand in for cyclic time, alongside. dragons, serpents and related creatures.

oh no you’re suddenly a werewolf! Except you’re not a wolf, you’re the a were-last wild animal you’ve seen on TV/read about/seen in real life

Elle Has Cats (and ADHD) (@ellle_em) February 15, 2021

THE HISTORY OF WEREWOLVES IN A NUTSHELL

Werewolf literally means ‘Man Wolf’. Were is from Old English ‘wer’ meaning ‘man’. The maleness of ‘were’ has since been lost in modern English, but if we wanted to seem technically accurate, the female equivalent would probably be ‘wifwolf’, and that’s not ideal in an age where women don’t always appreciate being referred to in relation to men. (Wif is the Old English word for ‘wife’, in an era where women did not exist as autonomous human beings, belonging only to fathers, husbands and sons.)

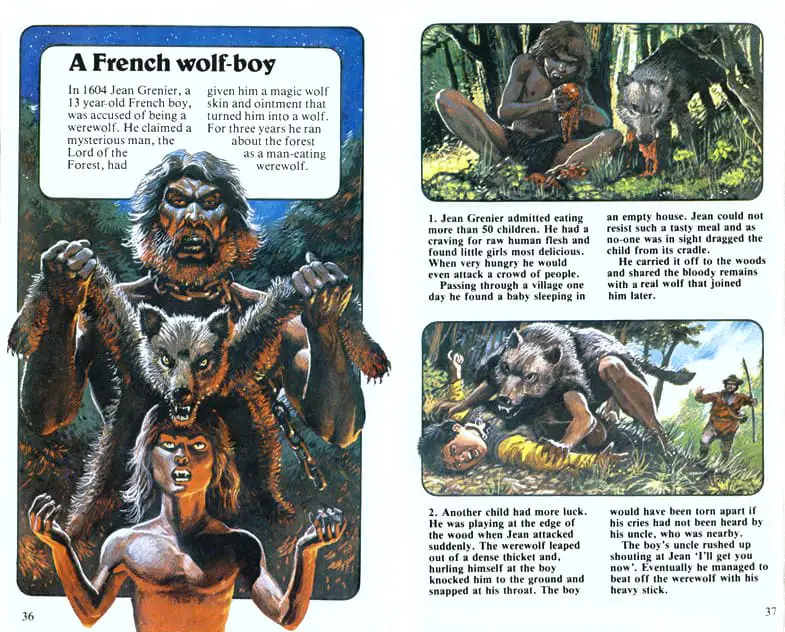

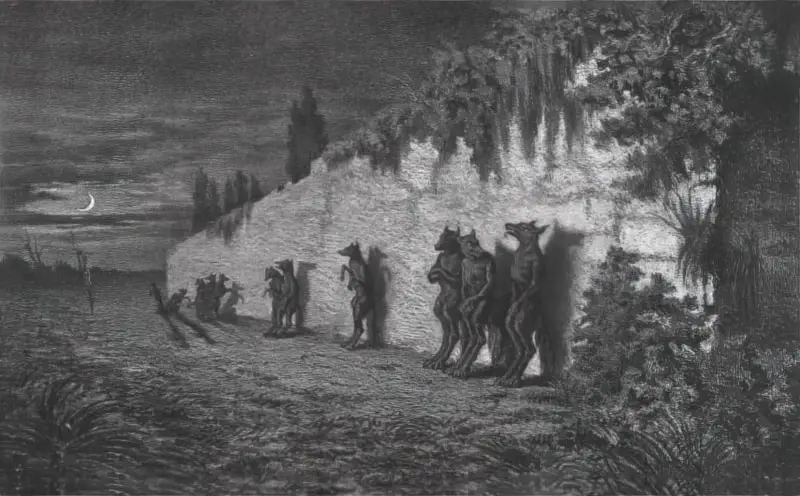

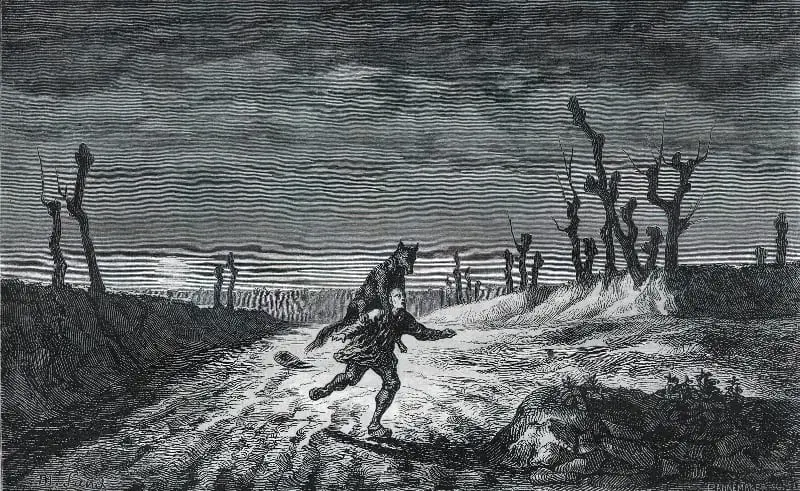

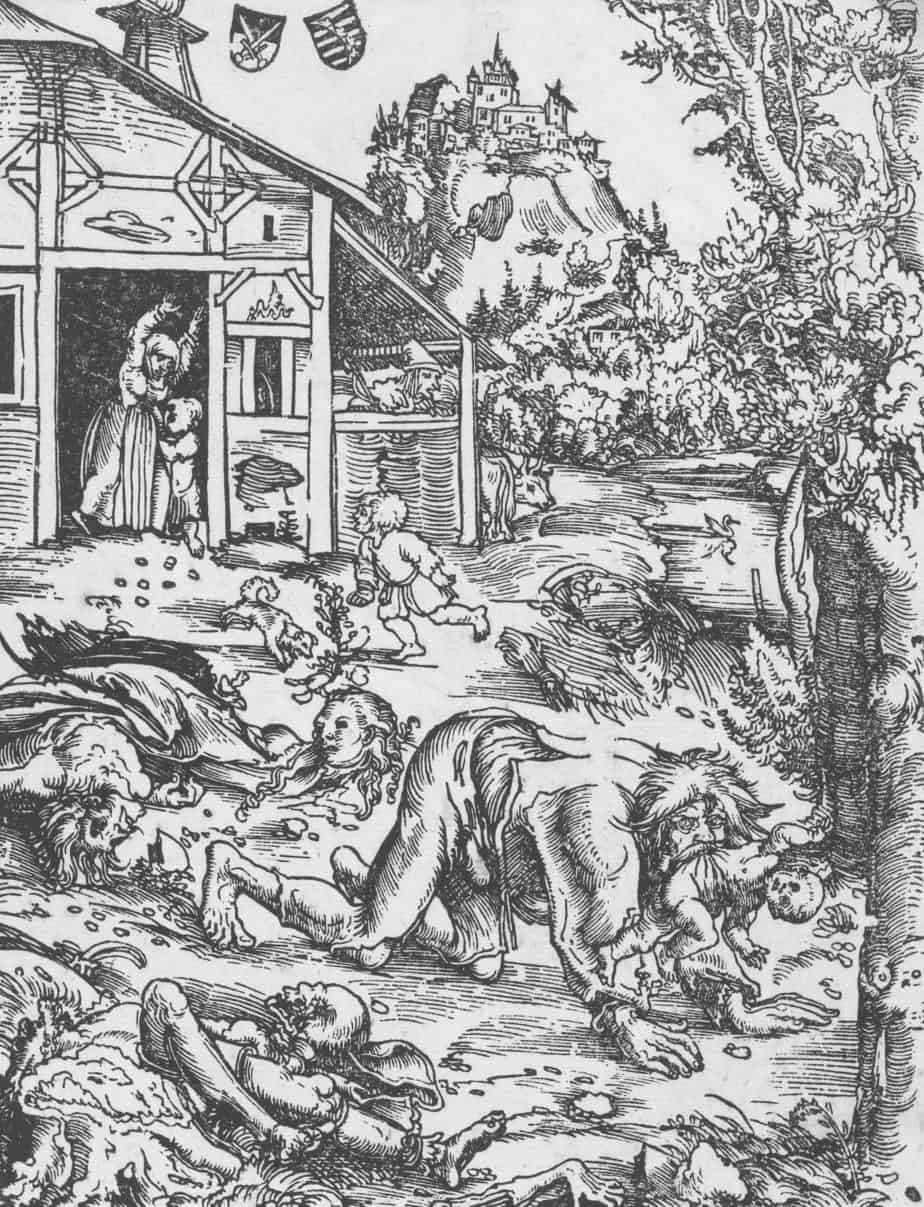

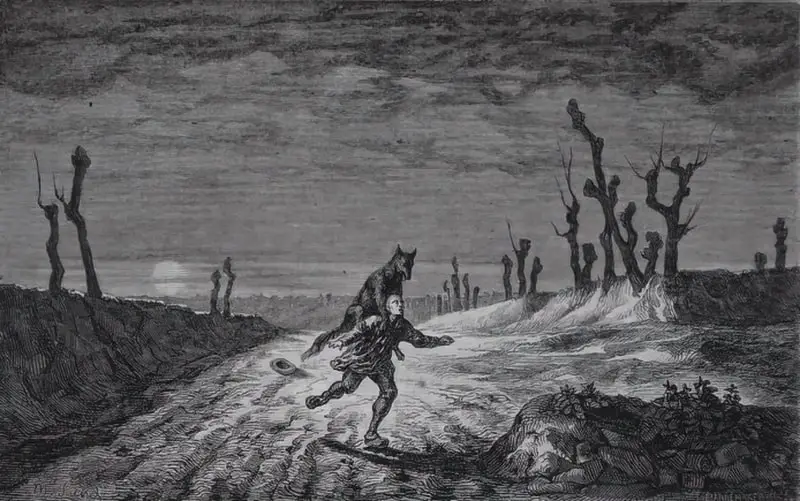

In Europe, people really used to believe werewolves were a thing. Imagine believing that. Imagine thinking that, if you weren’t careful, you yourself might turn into a werewolf. How would you regard the moon, if this were your worldview? Don’t know about you, but I’d stay inside on moonlit nights.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, reports of werewolves pervaded much of Central Europe and sections of France along the Swiss border, notably the Jura and the Franche-Comfte. The surgeon Johann Dietz witnessed a crowd of villagers in the northern German town of Itzehoe chase a werewolf with spears and stakes. Even Paris suffered sporadic attacks. In 1683, a werewolf on the Notre-Dame-de-Grace road supposedly saved a party that included several priests.

At Day’s Close, A. Roger Erkich

This dynamic picture book from an award-winning art director shows how feeling hangry can turn even the sweetest kid into a Wolfboy!

Wolfboy is hungry!

WEREWOLVES ACROSS CULTURES

Something about wolves that leads humans to think, across largely unrelated cultures, that people can turn into them. Horror storytellers have since turned all number of creatures into were-creatures, from horripilating to comedic effect and everything in between. Wallace and Gromit gave us the Curse of the Were-Rabbit, for instance, comedic because rabbits are not naturally terrifying (on their own).

The ‘were’ of ‘werewolf’ originally meant ‘man’ (man-wolf). This gendered meaning has largely been forgotten in contemporary English. We can therefore have female werewolves.

werewolves and the moon

There is a long history connecting moon cycles to changes in the human body:

Best known of the many “planets” said to influence the rhythms of everyday life was earth’s closest neighbour, the moon. While a welcome source of light, the moon reputedly affected the internal workings of the human body much as it did the flow and timing of ocean tides and the course of the weather. France’s “first philosophe”, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, was one of many learned authorities to perpetuate the medieval theory stressing the moon’s importance to physical health: “As it passes through its phase, it exerts a great influence for better or worse over the course of illnesses.” So potent was its power that the moon could alter the amount of moisture within a person’s body, including the brain, thereby driving some individuals insane or “moon-struck.” Observed the authors of Maison Rustique, or, the Countrey Farme (1616), the moon was the “governesse of all such humidities as are in earthly bodies.” When the moon was full, women were thought at particular risk to become “lunatics.” Some victims died on the spot. In London’s St. Botoloph’s Parish between 1583 and 1599, as many as twenty-two deaths were attributed to planetary influence.

At Day’s Close by A. Roger Ekirch

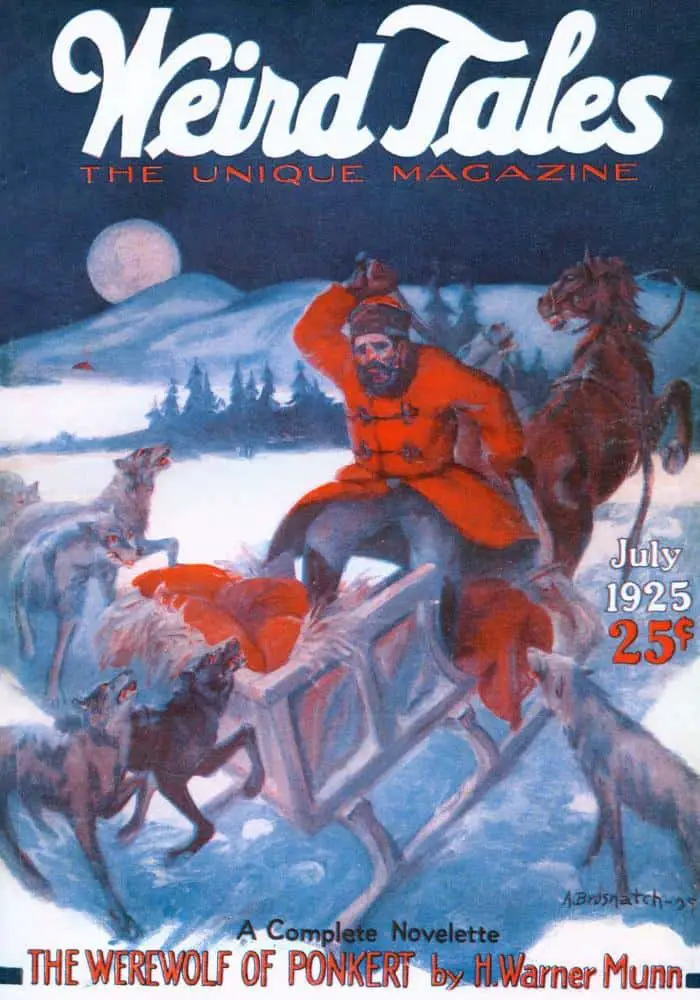

But the story which connected the moon so closely to werewolves for a modern audience was the 1941 Wolf Man movie. Earlier werewolf stories were more fairytale in nature. The person turning into the wolf tended to put on a certain item of clothing such as a magic belt or coat.

WEREWOLVES IN MODERN STORIES

When it comes to werewolf tropes, the tropes differ depending on the medium. Movie werewolves are most often supernatural horror villains, there for the gore and slashing, and could be swapped out with many other horror villains. For this reason, these werewolves are not particularly interesting.

Twilight shifted the status of werewolves — the character of Jacob paved the way for a modern werewolf who is also a potential love interest.

Werewolves can be used to convey many things, depending on the ideology of the storyteller. One common use of the werewolf (among various other wild animals) is as a proxy for overwhelming teenage sexuality:

It can be a hard thing to be a teenage girl. You face pressure from both your peers and society at large to rush into sexual activity you may not be ready for. You’re judged for your clothes, your makeup, your interests. You have to navigate that blurry line between childhood and adulthood, exemplified by physical changes that can make your body feel like it’s not your own.

Also, you might turn into a werewolf.

Or a mermaid.

Maybe a succubus.

At least that’s the case in the movies, where there exists a long and storied tradition of associating of female puberty with the supernatural.

Or, if you’re not into the whole brevity thing: “Help, I’m a teenage girl coming into my own as a sexual creature, while also turning into a literal creature who transforms into a deadly animal/can control objects with my mind / has an all-consuming hunger for human flesh / bites dudes’ junk off with my vagina” (circle where applicable).

Supernatural sexuality is nothing new at the movies.

It’s a horror subgenre that’s shown its face time and time again throughout the decades. In 1942’s Cat People, a sexually repressed young woman refuses to be intimate with her husband due to her (justified, as it turns out) fear that doing so will cause her to turn into the killer cat that looms so large in her people’s mythology.

Mashable

As such, the werewolf as sexual beast trope can be used to try and suppress sexuality, or to encourage readers to embrace it.

PROBLEMATIC WEREWOLF TROPES

The problem with many werewolf stories is that the wolf is based on inaccurate, outdated science, in which wolves were studied in captivity, not in the wild. When studied only in captivity, scientists came up with the following:

- In each pack there is an alpha male and an alpha female running things.

- The alpha male is more powerful than the alpha female.

- There will be wolves at the bottom of the hierarchy (omegas).

- Wolves mate for life.

In the wild:

- The parents are in charge of the pack. ‘Alpha male’ and ‘alpha female’ are mum and dad taking care of the teenagers. (Not so sexy now, right?)

- Wolves don’t mate for life.

- The ‘males are stronger than females’ thing is never so simplistic, whether we’re talking about animals or humans. It is a fantasy to imagine that men can protect us all. To take an example from a different species, it was only recently that researchers shared that male, alpha chimpanzees are only the alphas of the other males, and that an alpha male chimp can easily be dethroned if all the females decide to reject him. It is certain that the sexual hierarchy of wolf packs is equally nuanced and complicated as it is in chimpanzees.

If storytellers go with the captivity inaccuracies, this results in a romantic view of the (human) patriarchy, which is intimately connected to the One True Love story. We see this in Twilight, in which werewolf Jacob’s One True Love is Bella’s baby.

Consent is a complicated topic in storytelling because sexual fantasies are somewhat separate from what an audience will accept in reality. Or is the line really so clear? The very definition of ‘fantasy’ becomes muddied when narratees live in the real, non-fantasy world in which non-consensual activity happens to people frequently. Werewolf stories set up under the (human) patriarchal system require ‘underdogs’ do as they are told. While this hierarchy can pave the way for con-non-con fantasies, is it still a fantasy when the characters within the setting are unable to give their own consent? Con-non-con activities are in fact consensual. There is a dearth of stories modeling conversation which needs to take place beforehand. To what extent should stories model good behaviour? Does there need to be that wrapper story in which readers are gradually immersed further into the fantasy world?

As mentioned above, the alpha werewolf in a patriarchal werewolf story is more powerful than the alpha female. This is an uncritical presentation and serves to reinforce ‘the natural order of things’ (for humans).

Some werewolf stories present werewolf as analogue for disease. J.K. Rowling has said that in the Harry Potter series, the werewolf part stands for AIDs. Even if readers are supposed to get the message that ostracising werewolves (diseased people) is bad and we shouldn’t do it, the very act of writing a diseased character as a supernatural monster is in itself problematic, and perhaps relies too heavily on the audience’s ability to see the storyteller’s intent. Zombies are also used in this way.

Werewolves in modern stories are sometimes presented as protectors of nature, which is not problematic in its own right. It can become problematic once non-native writers include tokenistic, appropriated indigenous cultures and transfer those symbols onto wolves.

WHAT MAKES FOR A PROGRESSIVE WEREWOLF STORY?

In better stories, a werewolf can make for an interesting, rounded character in its own right. An adept storyteller can almost transport us into a canine body ourselves and send us running through the forest.

Modern werewolf stories tend to say one of the following:

- Friendship makes you stronger. The metaphor here is the wolf pack. Teen Wolf is a good example of that, with the additional message that ‘those in your pack don’t have to be wolves’, which conveys a message of diversity and ‘chosen family’.

- Werewolf stories can say something interesting about anger management, and the struggle to control one’s emotions.

- Werewolf stories can more generally be about Being Different — this plot is certainly not limited to werewolf stories.

WOLVES, TRANSFORMATION AND SEXUALITY

One modern and interesting way writers are using werewolves: As symbols for how hard it is to fit into the rules of the patriarchy.

The following example makes use of wolves rather than werewolves, but these wolves are functionally ‘were’- wolfish:

“St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” by Karen Russell is […] about a pack of wolf-girls sent away to live with nuns so they can transition into normal young women. I think Russell uses animals in this story as a symbol for the wildness in young people and how there is an expectation, especially for girls, to abandon rough or wild behaviour as they mature. It is about societal pressure, but it is also about the kinship people feel toward animals, and similarly the divide between animal and human that we can never traverse. Pulling from this set of examples, what are some of your favourite short stories and in what ways are animals used in them?

“Dear Amelia” by Anne Valente, explores a similar transformation in reverse. The story is narrated by a group of girls that is turning into Maine black bears, a secret that they keep to themselves. To me, this story is so much about the private discovery of the self as you come of age, an experience that is at once mysterious and magical. What better way to enact that than through this literal transformation?

The Masters Review

In the wilds of the Northern California mountains, all the inhabitants of a small town have gone missing. It’s as if the people picked up and left everything they owned behind. Fearing something supernatural might be going on, the FBI taps a source they’ve consulted in the past: the werewolves Charles Cornick and Anna Latham. But Charles and Anna soon find a deserted town is the least of the mysteries they face.

Death sings in the forest, and when it calls, Charles and Anna must answer. Something has awakened in the heart of the California mountains, something old and dangerous — and it has met werewolves before.

As night fell, something stirred the darkness. Birds shrieked, rising into the air as the peace cracked and fell apart. Flashes of crimson uniform cut the smothering black of the woods. The smell of smoke lifted through the boughs and choked the leaves. A drum beat out a steady pulse as soldiers tore over the dead leaf matter, hacking their way through the web of forest.

The prisoner ran.

When Lowell Sencha finds the strange girl lying as if dead on the riverbank, he is startled to find that she is like them: waer. Human, but able to assume the form of a wolf. The Sencha family’s small community has kept itself sequestered and unnoticed, free from persecution. The arrival of a fellow traveller, and a hunted one at that, threatens their very survival.

Sure enough, the soldiers of the blood-purist Daeman Leldh soon descend on the village searching for her, burning and slaughtering. Lowell and the mysterious stranger are among the few to escape. And now they must find their way to the city of Luthan where, she says, they will find people to help them bring down Daeman Leldh.

If she can persuade them not to kill her.

MORE ON WEREWOLVES

- A Goodreads list of the most popular Werewolf novels recently. Maggie Stiefvater’s Shiver series is near the top, and definitely the most popular young adult werewolf series. There is another entire list dedicated to Werewolf Erotica. Anyone who has read Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden may not be surprised at werewolf erotica because dogs make a surprisingly frequent appearance in female sexual fantasy.

- Review: Werewolves, Wolves and the Gothic from The Dark Arts Journal

- A lot of my ideas on werewolf tropes come from this Dirty Old Ladies podcast.

- The Dangers of Straying from the Path and Tales of Lycanthropy Part 1 – The Cautionary Warnings of Little Red Riding Hood and The Company of Wolves: Wanderings 38/52 from A Year In The Country