Once upon a time there lived three bears. They decided to live in a house after simply stumbling upon a cute cottage one day, in a wood. Also of note: They weren’t really bears. But they did look ursine from a distance. They looked ursine right now, in fact, setting out from their suspiciously acquired home in the early morn, wrapped in their thick fur coats—Papa, Mama and Baby in front, squealing at the white carpet of snow which had settled overnight.

“I brought a carrot for the nose!” said Papa Bear in his rough, gruff voice. “Keep watch for two round stones. We’ll use those for eyes!”

Nearby, Goldilocks shrank smaller into her scrubby hiding place. She no longer lived in a house of her own, though she did inhabit the wood.

She knew all who lived in the wood, though they did not know her. She had memorised their habits and their faces. Without introductions, she gave them her own poetic names.

The Bears had found her cart once, before she learnt to hide it in a pile of leaves. They wondered where it had come from and riffled through her things. Their excitement waned as they listed her worldly possessions: Three worn blankets, two darned socks, a skillet. Acorns, sticks, a blunt paring knife.

“A child must have left it,” they said.

After that, they seemed to sense her presence. They shuddered at the unwashed smell she left behind in their house. They scared the young one with tales of a stranger who peeped in through windows at night, and threatened him into compliance with tales of what she might do.

“I’ll heat you a bath, Baby. Aren’t you a wee willy stinky!”

“I don’t want a bath, Mama!”

“Goldilocks will come to get you! Do you want a new, wild mother? Do you? Do you, wee willy stinky?”

But they didn’t really seem to believe in her existence. The Bears half-wondered who used all the kindling. A long discussion ensued about who had stoked the fire that time when neither Mama nor Papa had lit it.

“Perhaps this cottage contains spirits,” said Mama, for they had not lived here long and did not know its history. “But sing out if you find anything gone.”

Nothing was gone. Nothing they’d notice.

The trio of Bears disappeared along the woodland trail. Goldilocks avoided the common paths but knew where the Bears were headed—to the clearing. They would build a snowman and hurl friendly balls of packed ice. Goldilocks knew to avoid such missiles. She had dodged flying objects before, but not because it was fun.

Next the Bears would visit the frozen lake. They’d taken a wicker basket and dangled their knife-soled boots as they wandered away from the cottage along the forest path. They would frolic until dusk, hollering all the while. They’d return in the late afternoon, hungry for a home-cooked meal.

When they were properly gone, Goldlilocks walked up to the house.

Out of habit, she made a fist and rubbed a circle into frozen glass. Next she peeped in at the keyhole, though she knew they were gone, all three. They hadn’t locked the door. They never locked it. She lifted the latch. The door creaked open.

The fire burned warm but would not last the day. She wanted to keep it alive. If she tended the fire, the cottage would remain toasty for the family’s return. She’d be doing a silent favour, but then they’d know someone had been there. And Baby had learned to fear ghosts. He woke at night screaming, and Goldilocks heard him. The whole wood heard him.

The breakfast table had been cleared and wiped. But a pot of slops sat near the stove—an evening gift for the pigs. One clean dollop of oatmeal could be rescued from its nest of potato peelings. Goldilocks took the lump and filled her mouth.

But these slops were a few days old. The cream had turned quite sour. Goldilocks swallowed anyhow, because porridge lined her stomach.

Then she spied a fresh bowl of oats, half eaten, with a small spoon sunk into it. Baby had left most of it, excited for a big day out. Surely they weren’t saving it for later.

Waste not, want not.

Goldilocks gulped Baby’s leftovers, using the bowl like a drinking mug. His porridge was a little on the cold side, but Goldilocks could not remember her last hot meal, so it felt just right to her. She was reminded how warm food feels, filling a chilly gut. She considered licking the bowl, partly to keep it from setting hard on ceramic, but she restrained her voracious, cold-weather appetite. With restraint, she’d leave a little for pigs. Then she’d replace the spoon and put the bowl back where it was.

She poked the fire, hoping to stir it up. Evidence be darned, she planned to spend a warm day sitting quietly, belly full and thinking about happier times passed. She could enjoy the dream of home, probably until vespers. How nice it would be to stay inside a warm cottage for an evening as well, to eat roast meat and potato on a middling-sized plate of her own. She could help with the mending and put Baby to bed. Oh, she knew plenty of bedtime tales. She could spin epic stories of chase, and of hide and seek. She’d warn him of predators, and he’d learn that anyone, anytime, can always lose their home. That’s the thing about lullabies—the words are lumpy but the tunes are treacle sweet.

Such was her dream. She’d be long gone by nightfall, of course. Meanwhile, she’d spend the day on restless alert, listening for voices and footfall.

One chair belonged to Mama, closest to the hearth to allow for sewing by night. Mama used a cushion for her bony rump. Papa required a sturdier construction, close to the ashtray, the Bible, the matches. Between them, nestled safely, would normally sit the Baby chair, though babies rarely need chairs, preferring floors for rolling around on and for stretching out long. He’d upturned his wee chair and there it propped, topsy-turvy, up against the wall.

This is not how Goldilocks remembered the arrangement. So she took the Baby chair and she set it upright for now, between Mama and Papa, safe as can be. She imagined her own Mama on one side, Papa on the other. She loved the smell of pipe. She detected the wraith of it lingering now. Papa Bear must have smoked one this morning, just as her own Papa did.

Lately, Goldilocks grew shorter as Baby grew taller. He’d grown too big for his child-sized chair. Goldilocks preferred it still—her swollen feet could rest flat on the floor. She so rarely got to sit like a lady. She normally squatted—an unladylike resting position in common with defecation. So she hitched up her long skirt of rags and sighed and she sank onto the little seat.

She didn’t sit; she sprawled.

It was not Goldilocks who broke it last night. Goldilocks had been nearby, sheltered by a hut of branches when Baby’s chair broke, trying to sleep through the cold. But inside the house, in front of the fire, there had been swinging and leaning, followed by cautions and admonishments. Baby Bear smashed his wee chair after leaning back hard. Mama tied its pieces together with twine, waiting for firmer nailing. The chair looked complete at first glance. But when Goldilocks sat, a leg splayed out and the bottom came free.

The old wee woman would have trouble getting up. If only she were young again, she could spring up like a startled rattler. She said a wicked word about the pain. She lay there for a very long time, taking inventory of her injuries. Pains were not new. She refused to dwell on those and made an escape plan.

First she would roll onto her left side. Next, rise upon all fours. From there she would grab the sturdy big Papa chair. She’d grasp its nearest leg with one gnarled fist, then heave-ho, up we go!

She rehearsed this manoeuvre in her mind. From the floor she could see through spicules decorating the front window. Snow whorled and the wind whistled. Goldilocks started to worry. With the sudden change of weather the Bears may cut their excursion short.

Eventually, after much effort, and far too long on the very hard floor, the old woman made it to her feet. She fell heaving and near sobbing into the big chair and realised she had collected a new pain after all—one dominant ache along her right side. She winced as she reached up to tighten her bun, which was always coming loose. White wisps glowed yellow against the embers. For a moment, lit by the fire, she wore the golden halo of childhood.

The fire made everything better.

But the big Papa chair felt hard as the floor. This damaged hip would require padding. If she were very careful, she might make it over to the Mama chair— the one with the cushioned seat. She could lurch over, almost, but then she’d sit upon knitting needles. It was no good. A chair wouldn’t do.

She could reach the poker from here. She snatched at it like it might attempt a quick getaway. Poker to floorboard, she hoisted herself up from the hard chair, off her agonising hip, and hobbled—thud, thud, thud—into the bed-chamber, poker as walking stick. She had no time to survey the arrangement of beds, but flopped, without really meaning to, onto the short mattress by the window.

The bed head was different and the linen fresh, but the view remained unchanged. From her pillow, the old woman gazed up at a familiar childhood view. Through the misty squall she counted the hilltops. She counted them as she had, many years ago: One two three, one two three, before she’d learned numbers to six.

Her bed was just right.

It was soft as cloud. A bony elbow would never gain purchase to prop up her back. Life is short but the nights are long. If only she’d spent more of them soft and warm like this.

She should have asked for more. She should have rattled the pots, washed in the tub and eaten her share of the meat. They would have noticed her then, with their wide red mouths and their flapping, furry coats. She should have stood her ground. She should have screamed to the hills.

They’d find her this time, where beginning meets end. She knew not to worry. Cold was setting in, and soon they’d all be home.

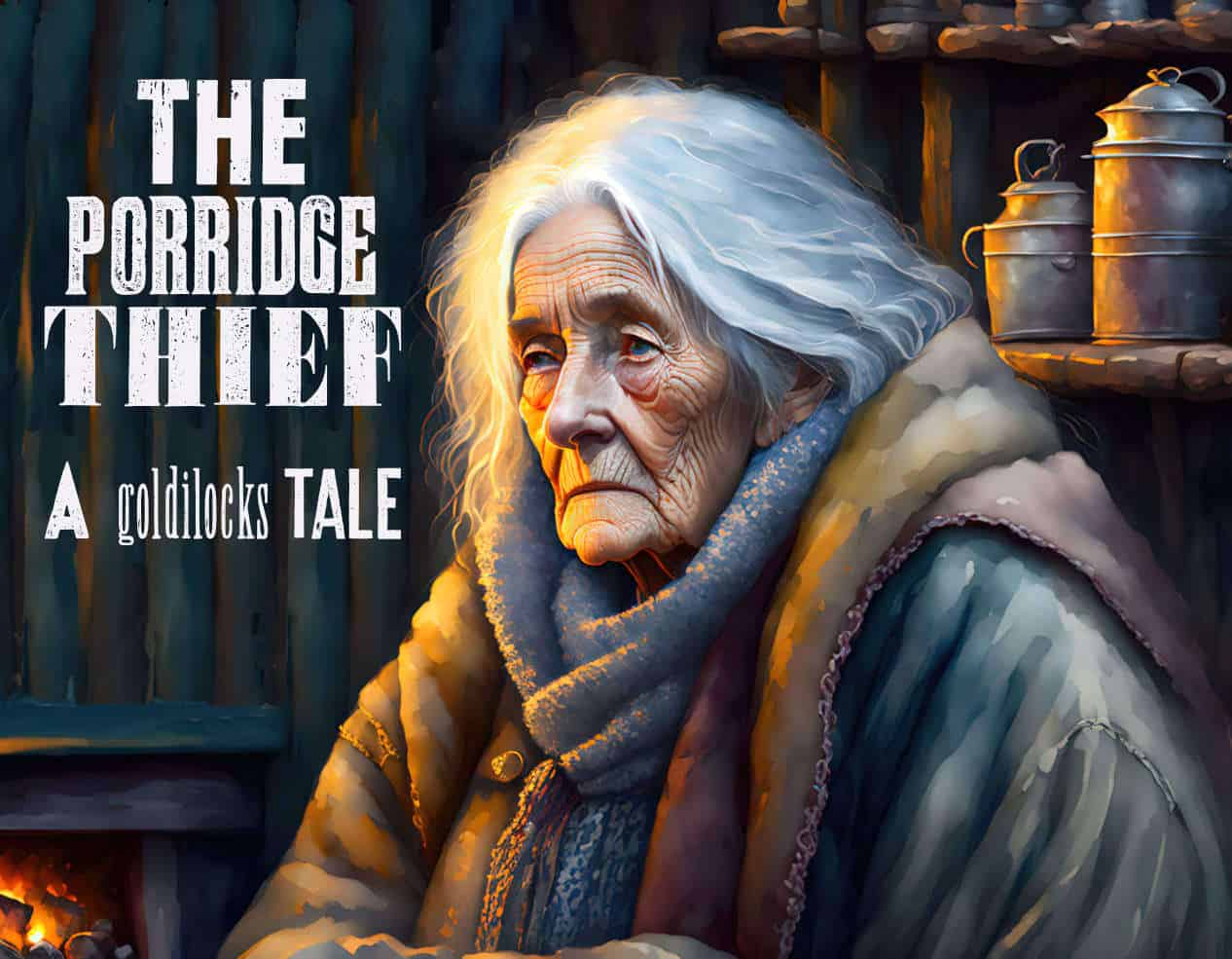

In earlier versions of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the person who breaks in to eat porridge is an elderly woman. How would the experience of breaking and entering be different if one were very old? This is basically a tale of homelessness. Older women have always been vulnerable to homelessness, invisibilized to the point where they may as well be ghosts.