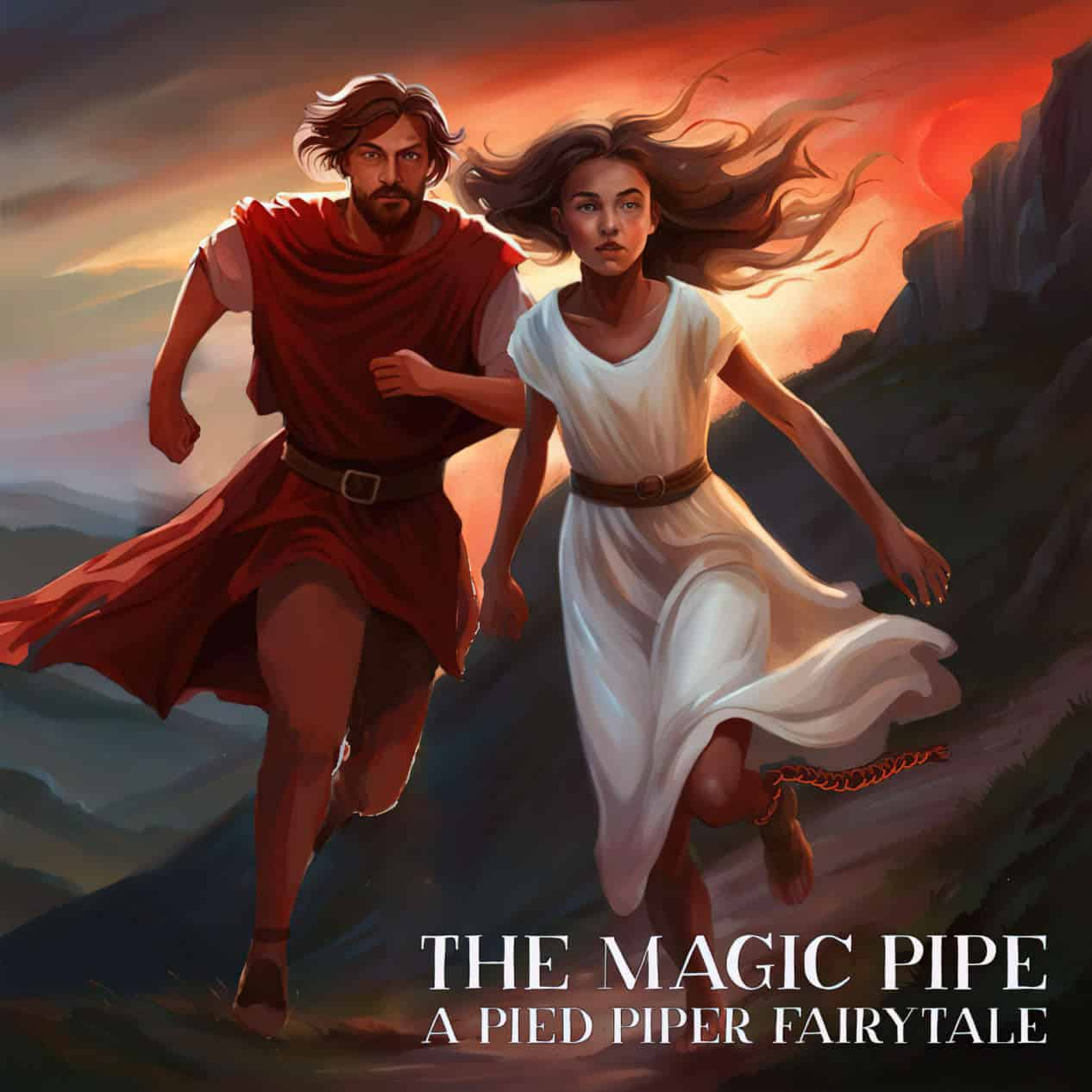

At least the girl wore white. The bright night-gown shimmered as she ran. The heavens thundered, and glowed as if burning.

In this early dead of morn, thunder woke him first. Then he heard the bells. Alfhelm had not stopped to fasten his footwear, which threatened to fly free as he pounded the ground. Despite this impediment he gained on the child as she crested the rise, toward the cavernous mountain. She glanced back at him with dark, cunning eyes, seeming to shrink even as he approached. She scrabbled up a steep bank, dropping to all fours; lithe, rat-like, and he did know rats. The whole of Hamelin knew rats.

Like the others, the child displayed uncanny agility. She clawed at the gravel, grasping with small, pink hands at deep-rooted plants as if she knew weeds, and had tasted their bitter roots.

But Alfhelm was bigger, faster, stronger. He caught the girl-rat by her tail of rope which trailed, half-chewed, from her left ankle. He wrapped it quick round his wrist and yanked her down hard, onto a flat of grass. He wrestled her onto her knobbly back. He pressed her sinewy arms to the earth and straddled her narrow waist. Like this she might not escape.

Oh, others had. Others had transfigured and squeezed free, even from death grips like this. Or the earth had revealed its ghostly portal, right there, right then, and Alf had seen it himself. He’d seen the earth open to trepan the children, leaving the grown behind to mourn.

But if Alfhelm were to wail a sleepsong, one he had learned in church, he might drown out the pipe. So he sang to the beat of a distant gong. He heard only church bells himself. At twenty-nine years of age, Alf was too old to hear the pipe spell himself. Men with beards and women with blood were immune from the tune; or such was the calculation.

Alfhelm wept as he sang to his captive.

“Lullay, lullay, la, lullay…”

The creature kept struggling, though her face resumed its human form.

Only then did he recognise the child—a young woman, he had thought—a talented spinster and companion to his wife.

“Fräulein Fischer?”

She gnashed and she squealed. This might have disturbed him greatly, and it had the first time he bore witness, running after children, who ran after night-music. But little could shock him now.

“Fräulein! Come back to us!” He wanted to slap her from her nightmare, but that did nothing; it only left marks. He had to stay like this, straddling and struggling, until the girl’s head-music abated.

Alf’s wife, encumbered by bawling babe, came panting up the incline. Other grim faces followed. They brandished sticks of fire.

“Blitza, you say?”

“Young Fräulein Fischer?

“Is that Blitza Fischer you saved?”

Alf let them see the girl for themselves.

Marlein covered her mouth in shock.

Alf addressed the small group. “How old is Blitza? Has she not been spinning for three full years? Has this one not come of age?”

Husband and wife locked shining eyes.

What more could be said? The Pied Piper had cleared Hamelin of rats. But then he returned for the children. They disappeared as the rats had, few by few, in the hours before dawn, when guardians fell into deep slumber.

Parents roped their young to their beds, but rat-children gnawed and they tore. They bit at their strongman keepers with jagged teeth, never to be worn smooth by a lifetime of grainy broth and grit bread.

Parents bolted the doors and stopped the windows, but rat-children still found gaps.

They sent their children to the monastery in a last-ditch attempt to save the remaining few.

“Grab them! Down them!” shouted the monks, startled from unintended snores.

“No, no, let the devils go!”

The monks stood frozen like altarpiece figurines as the last of Hamelin’s children scrambled from makeshift cages and shimmied through cracks out of the abbey. As sure as dawn swallows shadows, the mountain gobbled them up.

The Pied Piper took every last child. He took little deaf Poppo, who pressed his belly to the ground and drummed the dirt with backhands, as if he felt the terrible tabor. Right, left, right-right he paradiddled, faster and faster, then up he leapt, mountain-bound, on his dancing feet.

The pipe took little Albert, who followed the music as if it granted sight.

The pipe took Petrissa, who cast aside her cane and sallied forth toward the mountain portal as if propelled by the whip and lash of a proxy appendage.

And now the piper had come for a maiden, of sixteen years and four plus moons.

The enemy was expanding his range. Next he would come for them all.

The dwindling town of Hamelin comprised marauders and mourners; most were a little of both. A gaggle of old men hiked to the monastery to smash its stained glass windows. The monks were long since gone, selling their thoughts and prayers to a more auspicious town.

Mothers had little to occupy their hands—no mash to prepare, no children to clothe, no rooms worth sweeping.

Old women gathered around the fire pit in the village square. They chanted all the livelong day, hoarse and cracked, as if to draw the children back from their holes.

Alas, they weren’t witches. But one old hag, excluded from social gatherings, came in useful now. She stood on a box near the fire and repeated her night visions in well-rehearsed prose.

“First he sends his rats. The rats eat the grain, then we all are rats. I seen him.”

“What does he look like, old woman?”

“The terrible murrain wears piper’s robes, holed by rats but lined with ermine. He hides in the nearby woods, always waiting, always watching. Then he strikes again.”

“Where in the woods, exactly?”

“Oh, you’ll hear him before you see him.”

She said no more than that.

With nothing left but desperation, the strong young men of Hamelin divvied themselves in two. One cohort scoured the woods for the rag-tag jongleur, listening in vain for his pipe and tabor. The rest kept vigil in town, leaping after escapees whenever the church bells tolled and the sky thundered red.

Another three moons waxed and waned, against redder and redder skies. Still the huntsmen did not return with the Piper. Night-watch had not saved the children. Not a single, Godforsaken one.

But there was a twinkling of hope, in the shape of a newborn; Alf and Marlein’s babe, who squalled extra shifts in the night, tormented by music but unable to run on his rolled-pancake legs. Robust and kicking, the baby needed constant feeding and soiled his cloth as ever. For this reason, Marlein alone had not lost hope. She knew what she must do.

First, she must leave the baby with Alf.

“Don’t nod off,” she warned, knowing he’d been charged with vigil all night, all season. She’d seen what babies could do. One day they’re bleating blobs of flesh; the next they’re toddling toward the well, wondering how deep it goes down.

She knew not what the Piper could do. His magic remained mysterious. Her baby might break free of his swaddle and somersault up the mountain, or glide away on his blanket, gripping invisible notes in tight little fists.

Nor did she trust the grieving mothers, who might seize her baby as surrogate.

“You hear me, mein Herr? Sit up, now. Sit on the stool, and when you’ve stopped shaking, then you must pack.”

“Where are we going? What’s to be done?”

“I’m off to gather the nubile. The music came for Blitza. Any time now, the pipe may play for Lukas. Lukas is sixteen, I think.” Marlein counted on her fingers. “His friends, Hart and Ruthard. Linda and Nella. Each unmarried and under twenty. Glindis, Oss and Ordulf, too. You and I will lead them into the woods. With luck we’ll encounter the hunters. We’ll camp with them. Even if we don’t find the Hamelin hunters, the cloak of woods might save us.”

“I don’t know about that, my love. They say The Pied Piper waits in the woods.”

“Perhaps he waits in the woods knowing the woods are safe.”

Alf gazed at his son, asleep in his arms.

“There’s something about Hamelin, Alf,” Marlein continued. “This town alone was cursed with the rats, and now with the famine.”

If Marlein was hellbent on taking refuge in the woods, he and the babe would have to go with her. Apart from the pain of leaving his small family, Alf wished he’d been sent on the hunt. “I return no argument. Anywhere’s better than here.

Alfhelm’s boss gave Marlein his horses and cart, not expecting them back. Next, Marlein went to collect Blitza.

Blitza was a sobbing mess. There had been yet another game of chase. Someone else had saved her, just. She’d begged to be tied to the flagstaff, with a ball and chain normally reserved for criminals. Old women held blanket curtains whenever she needed the pot. Blitza refused to be untethered, even for that, lest the pipe start singing and transform her into rat flesh.

“Come with us, Blitza, far far from here.” If Marlein could not persuade her, no one could. Except for perhaps young Lukas, so Marlein went to his cottage.

Lukas threw his sack of worldly possessions onto the cart. Next they gathered the rest of Hamelin’s youth. Marlein crossed her heart and promised forlorn parents a safe and hasty return. She wasn’t sure she meant it, but she managed to sound persuasive.

And when the enchained Blitza saw Marlein pass back through with every last one of her friends, including Lukas, her beau, Blitza joined the troupe after all, as Marlein had predicted.

In sombre procession in front of the cart, Alf and Marlein walked the troupe out of Hamelin. Alf held the baby and led the horses. Marlein held the stick of fire. The in-betweeners strode behind in a funereal procession. All the weeping townsfolk lined High Street as they left. Some clutched onto knotted rags in the shape of malnourished babes. Marlein bid farewell as they passed, because now at least they would hear it from someone.

“Good bye, Mama, Papa.”

“Good bye, Oma.”

“Farewell, Opa.”

They walked and they walked, all afternoon, away from the mountain, away from the dreadful sunset. Weakened by recent events, Blitza lay down in the cart, along with their paltry, black-flecked provisions and nibbled assortment of blankets. Lukas was permitted to join her, threading his fingers through hers, cushioning her head with his concave belly.

When the heavens changed hue, young Blitza sat up in the cart. She was first to cover her ears. Marlein noticed because she’d watched them all closely.

“Do you hear it again, Blitza?”

Blitza wouldn’t answer. She only started to hum.

Marlein had memorised their ages, down to the nearest month. Blitza was youngest, at fourteen and two. Next youngest was Glinda, who closed her eyes and tugged at her earlobes.

Marlein’s heart lurched. “What is it, Glindis? Tell me!”

“I’m imagining things.”

“Maybe.”

They were outside Hamelin now. She’d hoped they’d all find safety here.

“Halt the horses, Alf!”

The clippity-clop yielded to silence.

“Listen, Glindis? Do you hear that pipe? Do you?”

Glindis stumbled in a tight, weary circle, looking back toward the jagged mountain, which met with pinkening sky.

Though impossible to describe to immune elders, Glindis did try. “The tune creeps up on you. It knells indistinct, like a ringing of ears before the hunger-faint. Next it comes with a gush of promise. Then pleasure.” Nature-lover Glindis had been offered a God-yield of sparrows brighter than peacocks, if only she entered the hole in the ground.

“I think I hear it, too.” Seventeen-year-old Hart mumbled and looked at the ground.

“Why didn’t you say something earlier? I told you all to speak up!” Marlein’s anger was borne of desperation. She held fire to each of their faces. Each of them heard it—its ill-will and murmurs—and all wished they could not.

“Get out of the cart, Luke. You too, Blitza.” She huddled them round her, gripping their shoulders tight. “Listen to the tune,” she cautioned, “but not too carefully. You must lead us away from the pipe. Do you understand? There must be a gap in his trap. Lead us through it together. But keep us away from Hamelin. Away from the mountain, too.”

The in-betweeners wondered if it came from the horizon of dark trees. Then they thought they saw a pale buttering of sky as it joined a yonder horizon, beyond rolling pastures and scrub. They linked arms and negotiated a route toward the hope of light. They would try an unexpected loop-route into the trees, away from the mountain, away from the red.

Pa-tum, pa-tum, the world thundered.

The baby began to cry. Marlein passed the fire stick to Alf and walked with babe to breast, though he fussed and wouldn’t latch. She hung back, so the in-betweeners might stealth together and listen close for the safety of silence.

Alf led the horses into the grass. They’d have to ditch their cart if the in-betweeners insisted on traversing ditches and fields.

Marlein tugged at her husband’s cloak. “What are they doing?”

Alf clicked his tongue for the horses and glanced at the elbow-linked youth. “They’re doing as you asked, gnädige Frau.”

“No, look! They’re loping toward the rise!”

Alf peered through the red and saw his wife was right. This wasn’t a mountain, though. Just a knoll. He glanced grimly back at the cart. “Call them back, Marlein. We must each carry our share.”

But Marlein gasped before he could finish his sentence. The in-betweeners had dispersed, and now they were running, scampering, as fast as their legs could carry them, thump, thump, leap, over the grassy dome until only their heads were visible.

Tired though he was, Alf sprang into action. He loped over the knoll, and already he counted some gone. One mis-stepped. He grabbed it by the waist and flung it over his shoulder. Another tripped and he grabbed that, too.

Shielded from view by the rise of the knoll, Marlein hushed her baby, hushed her own self.

Eventually Alf’s rat-captives ceased with the flailing. He’d barely held them both.

“Get off me!” they squealed, baring their pointed teeth.

“You’re safe, I have you.”

“Where am I?”

“Who am I?”

Alf un-kneed them and caught his own breath.

He’d rescued young Glindis, and Blitza twice now.

But the boys had gotten away: Hart and Ruthard and Oss and Ordulf, each in fulsome youth. Lukas, too. They were too fast for Alf, who was older and slower at twenty-nine. The incline licked the boys up. Just like that. Robust Linda and long-legged Nella followed them after, into the terrible void.

The diminished party returned to the cart. The heavens glowed and thundered.

Marlein dropped to the ground and lifted her chin toward Heaven.

“Why us?” she screamed. “Why now?”

No one deciphered the thunderous reply.

The horses needed hobbling. Their spirited eyes whitened and their whinnies pierced the air, so that Marlein wondered if livestock heard the pipe, too.

They dare not go anywhere. Not back, not forth. They might have tried the graveyard, where the dead are buried already, and whose ghosts might protect their own mounds. But the graveyard was too close to Hamelin.

Husband and wife slept sheltered by the cart, halfway between Hamelin and woods, baby between them and two surrogate daughters, the smallest and slowest of the in-betweeners. Marlein wished she could feed them, too. If only the girls were small again, but small in a good way, not in the way of rodents and dearth.

They sobbed all night. All of them cried, including Alf; Alf most deeply, hoping to drown out the pipe, if only to save Blitza and Glindis.

The thunderous flashing gave way to sunlight; timidly at first, then enough to start a fire and a thin breakfast of gruel.

A red sky made for cold mornings. They leaned into each other and passed the sipping pot.

What now? All four thought it and no one dared ask.

They needed a new plan. Something. Anything.

“We’ll finish our meal,” Marlein said, “then we’ll visit the bog.”

No one asked why, but they followed her anyhow, to a place only women knew. Marlein and Blitza and Glindis collected handfuls of moss. Alf watched on as they kneaded the sphagnum like dough between palms, and then he guessed its purpose. Marlein used much of it, especially after the birth of their son, when ten wombfuls of blood unclogged. Blood moss, she called it. It saved her tunics from impossible stains.

Alf turned away from the women’s business. “I’ll meet you back at the woodland path.”

As he waited he stroked the horses and cooed to the baby, and wondered why the girls needed blood moss if they also heard the pipe.

But they had found a new use for it. Now they walked toward him, poking it into their ears, checking it would stay.

“Do you hear me, Glindis?” asked Blitza.

“A little.”

“Here, use more.”

Marlein looked spent. Though blood moss contained its own protective magic, it would never save girls from night-pipe.

Marlein took Alf by the hand and, moss-ears notwithstanding, she led him into the shrubbery so Blitza and Glindis could not overhear. She put one palm to his beard.

“The girls have worked it out,” she whispered. “They discussed it between them yesterday, and now they are sure.”

“What do you mean?”

“They worked out who he’s taking, exactly. The line between young and old.”

“Is it not the beards and the blood?”

Marlein shook her head. “These two have bled with the moon. A handful of times each, before the rats and the sickness. They know what moss is for.”

“Then what divides child from elder?”

“There’s another kind of blood, Alfie. It’s that.”

Alf considered this. “We’ve been wrong about much already.”

“We have.”

Marlein kissed her husband, who pulled away, needing to speak. “What are you asking of me, Liebling?”

Marlein beseeched him with her eyes.

“Oh, no. That’s unholy, that’s wrong.”

“So, so much is wrong. They asked me, Alfie. They pleaded for favour back at the bog. Is it not worth a try? Men giveth, though the piper taketh away. You did put our baby in me, remember? If that’s not counter-magic, I don’t know what is.”

’Twas not yet noon. Alf strode ahead, deep in thought. He’d promised Marlein an answer before nightfall.

But first they’d walk, further into the woods. With luck and prayer they’d encounter the Hamelin hunting party. Many were bachelors. Alf considered the group. His thoughts lingered on one name in particular—his friend Bolt Jäger. At twenty-three, Bolt was already widowed. Experienced, but not too experienced. He lost his wife to the plague but remained strong and healthy himself. Bolt was the quiet type. He spoke kindly of women. Indeed, Bolt Jäger was the clear choice.

He voiced these thoughts to Marlein.

“And you expect to find Bolt Jäger before nightfall?” Marlein seemed angry.

“Perchance we will.”

“In this vast, sprawling greenwood? Really, Alfhelm? We’ll find the Piper first.”

Blitza and Glindis lingered behind, as they had all day, ever since the bog of blood moss. The troupe had long since abandoned their cart. The girls led one horse each. They eyed Alf with… what? He couldn’t fathom. An unnerving admixture of desire and fear? They whispered to each other from a distance and he knew he was the object of their thoughts. He wanted to scream at his wife. How dare she offer him up? How dare she consider lending him out!

In the late afternoon, Marlein demanded Alf’s answer, either way. “We’ll never find the hunters,” she said. “Not before sundown.”

“The dark of trees makes the day seem later. Let’s wait.”

“It is late, Alf. It’s late, it’s late, and the girls are terrified.”

“They’re terrified of me,” he spluttered. “To them I’m as bad as The Piper. Don’t you see that? You haven’t thought this through. What if I put babies inside them? What then?”

“We’ll raise them as our own. Lord knows, Hamelin needs babies.”

“And if the girls wish to mother their own, to build their own families?”

“We’ll live together as family. I accept them as sisters, or daughters. It doesn’t matter. Apart from that, these two haven’t used blood moss in months. I doubt that would happen.”

“But, if?” Alf wished he knew exactly how babies came about. Women seemed to know more on this topic, but kept it between God and themselves. Alf did not know why babies came some times and other times not. He knew his stiff member was key. Without the Godlike intervention of their husbands, women rarely managed it.

“Am I to support three wives,” he whispered, “against the Church?”

Marlein was reassured by this question. “You’re thinking about it, then.”

“By the face of God! I’ve thought of little else.”

“Lend them your night-magic. Please, Alfie. Do it for us. For all of us.”

Alf glanced back at the girls. They held thin hands to their ears. He didn’t want to run anymore. He didn’t think he could. “Talk me through it,” he whispered. “And then we’ll decide together.”

They found a clearing roofed by leaves. A little of the heavenly red fretted through. They built a new campfire.

This took some time. Blitza and Glindis gathered wood while Alf meditated with the flint and fire-iron. No one thought of eating, so they drank from the nearby river and declared the night a fast.

Marlein filled and refilled the flask. She’d use water somehow, as priests do in church. This act, this heathen workaround, required a stopgap ceremony. They’d devise their own ritual, alone as newfound family, sheltered from civilisation in their cathedral of leaves.

Marlein prepared a bed of heather. She made it thick and wide, and then she collected rocks. She enclosed the mattress in a hallowed stony circle.

She held two twigs in her fist. Blitza drew the long one and wanted the whole thing over.

“Alfie. It’s time.”

By rights it should be dark. Diffuse shafts of red peeked through the branches and danced with wicked pleasure.

“My man won’t hurt you,” Marlein whispered, forehead against foreheads. “He is good, he is kind. Close your eyes and think of your own poor beaus.”

Blitza could not think of Lukas. Not without tears and losing herself to nature.

Alf was standing by the heather mattress, facing away. At first she thought he was passing water. Then she guessed he was preparing his equipment. Despite the chill his surcoat was off. So was his tunic. He’d used his garments to cover the heather. He’d done that for her, for Blitza, who’d be pinned underneath against rough spikes; or perhaps Marlein had suggested the gesture.

“Alfhelm?” She tried not to squeak, but it came out wrong.

He turned to face her, though she could not make out his face. He stepped forward, into a shaft of light. His abdomen uncloaked from its deep triangle of shadow.

“Do you hear the pipes?” he asked.

Blitza nodded.

Perhaps Alf also planned to keep his eyes closed. He hadn’t seen her nod. “Do you, Blitza? Do you hear them now?”

“A little,” she replied.

“And you’re sure you want this?”

Why was he asking? What did that mean, anyway? Want, hunger, all the things she’d felt for Lukas… She knew desire and this wasn’t it, exactly. But her friend’s powerful husband had saved her mortal soul, not once but twice, and Blitza had returned both times to the firmness of him, the enchanting smokewood scent of him, pressing her to the ground like a warm and heavy blanket. She wanted him, in a way, but she did not want this. Not with that nightmare pipe as ambience, rising and falling in pitch. Moss in the ears did nothing to quell it. She’d pulled hers out.

“Lie down, then.” He spoke quietly, with resignation.

Blitza suspected he saw the rat in her. He’d seen her at her most base, as she shrieked and scrabbled and ran, knobble-spined and black-eyed and covered in fine, downy hair. She wore the hair still. It covered her arms and her legs, and also her shoulders and back. It grew to warm her bones, her spindly child-like bones, lately lacking in meat. The rats had brought the hunger and now they were all part rat.

Blitza lay on the heather, atop Alf’s clothing. She closed her eyes.

“Hold me down,” she said, “as you did before.”

She only wanted to scamper.

He did as she asked. Then he began his chant, which did not drown out the pipe, but only enhanced it. His deep voice meshed and melded into the screech of it, making it better, making it worse.

“Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace.

Where hate rules, let me bring love,

Where malice, forgiveness.”

“Please just do it, Alf. I’m begging you.”

He didn’t object to her calling him by his familiar name. He gripped her wrists and straddled, only this time he thrusted too.

“O Master, let me strive to comfort others,

To understand others,

To love others, more than to be loved!”

Why was he chanting of love? Blitza felt warm droplets fall upon her cheek. He wept as he pressed into her, and he choked as he spoke, thrusting intermittently.

“For he who gives, receives,

He who forgets himself, find—”

“Finish, Alf. Please finish.”

He slumped on top of her in a heavy, slobbery mess. “I’m sorry, I can’t. I can’t let go, but that should be enough.”

He gathered the strength to roll free of her. Cold and shivering, Blitza reached down with one hand. She felt a new wetness. She held two fingers close to her face, to be sure the moisture was blood. Bright red it was, under the night-red shafts. This was different from moon blood—more like that of a wound. She was safe now—permanently impervious to childhood dangers.

Everything was better.

“Lord have mercy,” she said. “You saved me, Alf. I mean it.”

He hunched naked on the ground and she wanted to stroke his head, to offer comfort. But comfort wasn’t hers to give.

And for Alf it wasn’t over.

Blitza pulled down her tunic and returned to the campfire. She stung a little in the sacred chamber, but he’d done it gently and hadn’t lingered.

Glindis sat alone, hugging herself and scratching at her arms. Marlein was equally unavailable as comfort. Through the trees, Alf’s proper wife waded knee-deep in the river, cradling her baby, drowning out her own bad music. Even from the campfire, over the swiftness of river, Glindis and Blitza could hear her pray.

Blitza whispered to Glindis. “It wasn’t awful. Go to him now, or the devil’s pipe will get you.”

Against the flame, Glindis flickered a deathly hue. But she went to the mattress of heather, ears poked with moss, mouthing her own incantation.

Blitza sat alone. The fire looked the same. It would always remind Blitza of piper’s sky. But now she was immune to it. She would not succumb to the grip of his spell. One earthly man had countered the evil. That’s all it took. A few deep thrusts of manly magic and everything about her was changed forever.

Perhaps relief was meant to be brief. Now she must wallow in sadness; for all the missing children, and for kith and kin who’d died in their beds.

Join us! Join us, they whispered, calling through the trees, for Alf’s counter pipe was not magic after all. The campfire brightened and bulged. Blitza rose up, filled with joy. The trees grew skyward and weeds grew into trees. She tumbled after the whispers; bounding, skittering, careening through woods, twisting into the undergrowth, searching for an earthly escape. Birth must have felt like this. It no longer mattered but now she knew; a man’s sacred pipe is naught but appendage—nothing magic, but a bolt of beautiful flesh.

If you’ve wondered what long-listed Commonwealth Short Story prize entries look like, you’ve just read an example.

I wrote this fractured tale after reading The Legend of the Pied Piper. I wondered at what point adolescents became immune to the Piper’s magic music. Was it when they turned a certain age in years? Or was it when they went through puberty? Puberty takes a while. So there must have been a period during which adolescents were maybe immune to it, maybe not, right in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood.

For girls ‘womanhood’ is clearly marked by the menarche, but what if everyone in your town is starving and you aren’t menstruating because of underweight. What would make you a woman then?

There was one obvious answer to that, and I thought of all those stories, and the dominant cultural narrative, in which a woman’s virginity is marked by one particular act, and this act requires a man.

We’re also living in the era of the Strong Man leader, and I made sure to end this re-visioning to subvert the narrative that a man can save us all. Societal improvement is always, always a community effort.