**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Tell Me Yes Or No” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. Find it in Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You (1974).

This story is a case study of a narrative which may be true at a surface level but, as the story goes on, readers are encouraged to wonder if events really happened. Perhaps they are happening only inside the narrator’s imagination. Once readers start to doubt the veracity of one thing, we start to doubt it all.

Namely, does the narrator really visit the bookshop owned by her ex-lover’s wife? Is there really another younger woman? Wait, does the lover even exist? Maybe the man exists but was never her lover? Maybe she has some kind of parasocial relationship going on with some randomly picked journalist who writes for the paper. Journalists have name recognition but they’re not celebrities, as such. If this narrator is in possession of the journalist’s name and articles and nothing else then she has just enough information to construct a full-blown narrative about the guy without ever having to suffer from the slap-in-the-face that her celebrity crush just got engaged to someone else, or whatever.

Alternatively, she has met the journalist. They were students at the same time, as she says on paper. But they only went on one walk together, back when she was a new mother. Everything after that could be fabricated…

What the hell is going on here?

That’s not the point. Hermeneutical transparency is not the point. This short story is about the emotions of a woman who is coming to terms with some kind of absence in her love life. She may be fabricating some of it (or all of it!) as a coping mechanism.

ON COPING MECHANISMS

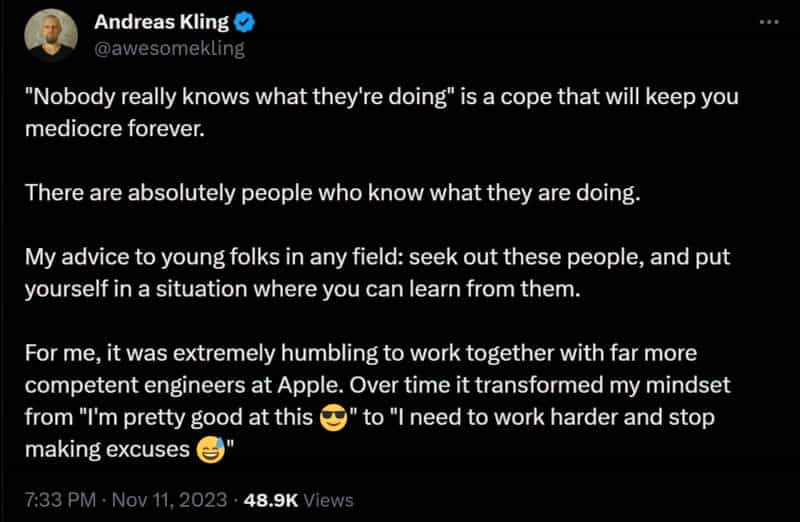

If you’ve been on social media lately you may have noticed young English speakers using ‘cope’ as a noun — a shortening of ‘coping mechanism’ but widening to mean something like ‘excuse’ or ‘deception’. Therapy speak has become mainstream or, putting it more kindly, most people are more emotionally literate these days and this is reflected in our everyday language. Naturally, words which used to mean something specific in the context of academia change meaning as they proliferate (for better or for worse).

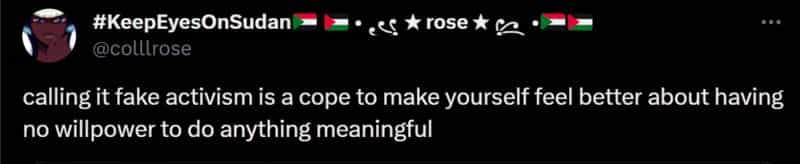

Here are two examples of tweets which use ‘cope’ as a noun:

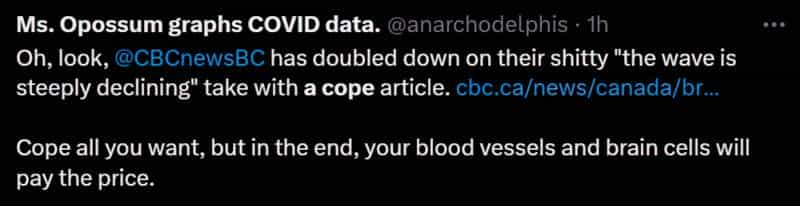

And here is an example of someone using ‘cope’ first as an adjective, then as a verb:

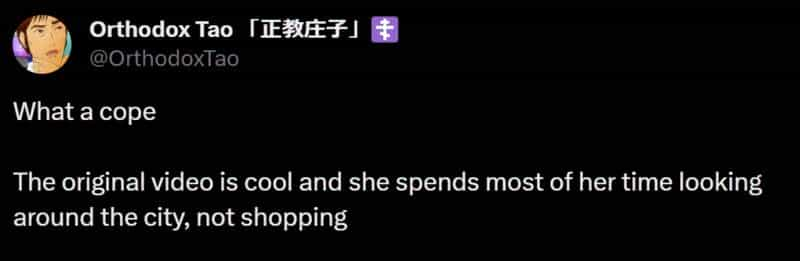

“What a cope” is a general insult, directed at people who say something disagreeable, with the added dimension that the person saying it is only fooling themselves to feel better about something:

THE SURFACE LEVEL READING

Let’s say, for now, that Alice Munro’s bereft narrator has no imagination to speak of and everything she confides here is true.

- The narrator marries while still at university. She has married the man who got her pregnant. They live together in campus accommodation built for families.

- Also on campus: A mature student, a man, who is back at university studying journalism. He later becomes a journalist.

- One day the pair of them go for a nature walk with the narrator’s baby in a pram. It feels like a date.

- The journalist and the narrator start an affair which lasts an indeterminate length of time — probably over years.

- The narrator’s marriage ends. The journalist is married to another woman.

- The narrator briefly sees someone else, but that ends with him telling her she needs to see a psychologist.

- At some point the narrator stops hearing from her lover. She reads in the paper that he has died.

- To cope with the sudden loss, she is drawn to her deceased lover’s home town, where she has no real plans other than to look at his environment and take things in.

- Eventually she finds herself in the bookshop of the dead lover’s wife. She lingers and observers.

- Meanwhile, her presence has been noticed. Eventually, she is approached by the wife who hands her a wad of her own letters. The wife tells the narrator to make herself scarce. Now she has her letters back, she doesn’t want to see her again.

- Mortified, the narrator retreats, but once she reads the opened letters she realises these are not from herself. They’re from some other woman. The other woman has a young child. The letters must be from one of his other lovers. How many are there, and who is this other-other woman?

- Knowing nothing about her other than her name, the name of her daughter and a few other details, the narrator constructs a persona. She basically imagines this other woman as a younger, more sophisticated version of herself.

- She returns to the bookshop and tells the wife that she is not the woman who wrote these letters. But she withholds the truth — that she did write letters, many of them. Just not these particular letters.

- Now it’s the wife’s turn to be mortified. She admits to feeling exposed. This stranger knows more about her life than her own friends and employees. They have no idea the bookshop owner’s husband was a philanderer. If they knew that, she’d suffer shame.

WHAT IS THE NARRATOR COPING WITH?

Who knows, exactly? Including the narrator herself. Sucked into a vortex, the narrator doesn’t have much idea what she’s doing. Perhaps she’s motivated by:

- divorce

- or maybe she never got divorced and is simply lonely within her marriage

- post natal depression which endured

- general loneliness, exacerbated by the fact that her two daughters are now grown

- the ambiguous loss of her university lover, who remained married to someone else

- the loss of her youth

- which is always about coping with our own impending death…

THE TITLE

Let’s think about the title for a moment. At first I was baffled by it. I couldn’t immediately work out the identity of the addressee in this short story. Who is ‘you’? We learn the ‘you’ is the dead journalist, but what of the title? What’s the yes or no question?

I believe the imaginary journalist lover has stopped replying to the narrator’s letters. It’s also possible he never replied to any of them. It’s also possible the narrator wrote them but never sent them. Or the writer thought of things about him, but never wrote anything down. (Basically, this story serves as a mindf*ck for the reader, as we are drawn into the spiralling misery of our narrator.)

It’s also possible the narrator wrote the letters herself but made her life more interesting in a catfishing kind of way. She even invented a different name for herself. Perhaps this was the game she and the journalist played together, or perhaps the journalist had already died… Maybe these letters are designed only to upset the grieving wife?! What the hell. Which part is true? Which part is false? Yes, no, which?

As for the entreating part of the title, I imagine the narrator has sent the journalist a letter asking something like, “Are you officially breaking things off with me? Just tell me yes or no!” But for whatever reason she has not received any reply. This is literally driving her mad.

IT’S GRIPPY SOCK TIME!

- Perhaps she imagines he’s dead.

- She imagines meeting his wife by visiting her bookshop. But maybe the wife doesn’t even have a bookshop. Maybe the narrator is in her local bookshop browsing for reading material (we are told she’s a reader) and she casts the owner of the bookshop as her lover’s wife. There’s something about a bookshop, any bookshop, which encourages flights of fancy. That’s what they’re for.

- While inside the heterotopia of a bookshop, she imagines the journalist has replaced her with a younger model, someone with a young child and dark hair: in short, a replacement model of her younger self.

DARK > GREY HAIR

That dark hair is important. Notice how the narrator mentions several times about how she quit dying her hair. This marked the end of her youth. But like many women coming to terms with middle age, to suddenly start ‘looking your age’ is a massive psychological hurdle. For straight women especially, youth too often require male desire, evinced by the male gaze of a lover.

Not all men are drawn permanently to youthful women, of course, but it is true for a large swathe of men. These types concentrate in the cohort of married men who seek out younger women for extramarital affairs. If this narrator once was the younger woman, then she understands exactly how youth is her currency.

Foolishly, she has fallen in love with the guy, or in love with the idea of the guy, whose main value to her was reinforcing her value as a young person. A young woman. If only she could give up the idea of herself as a young woman, she could give up the idea of him.

Love and hate are at the same end of a spectrum of caring. Either you don’t care, or you have strong feelings for someone. Strong feelings: love or hate, both.

That’s why she wants to kill him. By declaring this wish in the opening paragraph, Alice Munro utilises the technique of a thriller writer. Readers ask, “Just how unhinged is this narrator? Am I about to witness a murder here?”

AMBIGUOUS LOSS

Ambiguous loss is a term which comes from Dr Pauline Boss. Alice Munro has revisited the ambiguity of loss numerous times across her corpus of short stories, for example in “Moons of Jupiter” and in her stories about mothers who have become estranged from their adult children e.g. “Deep Holes“. Munro’s “Silence” is also about ambiguous loss.

A specific form of ambiguous loss occurs when you’ve been having a love affair with someone on the sly. The object of your affection is publicly together with someone else (e.g. married to another woman), in which case you must grieve his death in private, and without emotional support extended to spouses as the community rallies around.

Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain” also deals with this subcategory of ambiguous loss, as does A Single Man (based on a true story). Both of these stories illuminate homophobia, and its impact on gay men whose love is as deep and real as can be.

THE PLOT SHAPE OF “TELL ME YES OR NO”

Stories have shapes. Most stories are linear. Another popular shape is linear circular. But then you’ve got stories which circle round and around as the narrator tries to work out their feelings about something. Or perhaps they’re descending into psychosis. Maybe they’re trapped in delusion. These are spiral or vortex shaped plots.

Some lyrical writers seem very aware of the shapes of their plots. They repeat the macro shape at the micro level e.g. with their use of motif and symbolism. Another short story writer who does this very well is Stuart Dybek. (See “Pet Milk” and “We Didn’t“.)

I wonder if first person retrospective narratives — especially obsessive ones — might naturally follow a vortex. It’s how I’ve found lyric memoir to work; maybe it’s true of fictive versions of retrospection, too. A preoccupied (haunted?) narrator turns around and around in her hands the most potent moments of her past, gazing at repeating patterns and shapes as she spins. I see this happening — almost literally see a narrator turning a magic spindle in her hands — in Kincaid’s Mr. Potter.

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral Explode.

Alice Munro also makes use of the spiral plot shape a later story, “Miles City, Montana“.

In both examples, a woman narrator looks retrospectively at her past trying to come to terms with something. In “Tell Me Yes Or No”, a potential lover tells the narrator she “should see somebody”. Instead of seeing a psychologist she tells her story to us, her imaginary audience. She sees us in her mind’s eye.

YOU SHOULD SEE (IMAGINE?) SOMEONE

But let’s dwell for a moment on that idiomatic expression “You should see someone”. English speakers know that the ‘someone’ is a ‘psychologist’. But if we take it less literally, the narrator of this story is ‘seeing’ a cast of characters in her imagination. To imagine is her therapy. She sees her lover in his married life. She sees his wife working in the bookstore. She even ‘sees’ his new lover — easiest to imagine as a younger iteration of herself, because it’s more difficult to imagine him falling in love with anyone other than her. (A blonde, child-free woman, for example.)

By cloning herself and inserting the younger version into the narrative, the narrator of “Tell Me Yes Or No” creates a spiral. Whereas a ‘circle of life’ is the ‘healthy’ and ‘natural’ way of the world (we live, we procreate, we die), our narrator is caught up in a toxic version which feels out of her control. Sticking with water metaphors, if the ‘healthy circle of life’ can be compared to the gentle cycle of precipitation, the toxic version is a whirlpool. The narrator doesn’t so much choose to visit the bookshop then linger and watch. She’s sucked into it.

On the other hand, we might also argue that there’s a fractal shape to this story. The narrator begins with the story of her younger self having an affair, which leads into another story (the part that happens in the bookshop) and then another story (about the other-other woman). I would say there’s a fractal element to this overall spiralling plot shape. (The shapes overlap.)

WE ALL IMAGINE EACH OTHER

We can never fully know another person. We can’t fully know this narrator, and that is the point. Who, ever, anywhere, is telling us the truth?

Alice Munro explores this idea elsewhere, and even in this same collection, for example in “Material” — another story of a divorced woman who thinks about how her first husband, a writer, constructs a professional persona. Even her second husband may not be the man he says he is. What can we ever really know about someone else, even if they are our lover?

In any relationship, we construct parts of the other person. In romantic relationships, we tend to imagine they are better than they really are. Then, when things turn sour, we imagine they’ve moved on to someone better than us.

Alice Munro isn’t limiting this observation to women who find themselves as The Bit on the Side. She is saying this applies to all relationships, even long-standing marriages. When the narrator visits the wife, the wife admits to this one person in the world that no one else outside the marriage knows what was going on. And it would seem she kept her husband’s philandering to herself. She let him have his secret side, as she perhaps has hers, even if she finds it entirely in the imaginative world of fiction.

There’s an inherent loneliness to this solipsism. If no one is exactly who we think they are, then who are they? Is it enough that we are all in love with self-originating constructions of people?