Princess Cyd is a 2017 independent film written and directed by Stephen Cone. What I love about indie films, alongside the original plots and subversions of yawn-inducing blockbusters: I haven’t usually seen the actors in anything else. When an actor becomes a household name, that pulls me out of the story. I prefer not to recognise Actors.

A 16-year-old girl visits her aunt in Chicago for the summer. While there, she falls for another girl, and she and her aunt challenge each other’s sex and spirit.

log line of Princess Cyd

Young star Jessie Pinnick (born 1993) looks a lot like Florence Pugh. Rebecca Spence plays Miranda Ruth, her aunt. They’re both great.

I first saw Princess Cyd a few years ago but I don’t think I persevered with it. It looked to be something else, something I’m done with already.

This highlights a problem with films which ultimately subvert: The set-up of a subversive story tends to look a lot like… hoary old plot. The set-up to Princess Cyd looks like yet another story about a young, sexually free young person who descends upon her spinster, sexless aunt to teach the aunt a thing or two about loosening up, getting a boyfriend and enjoying life by having partnered sex.

But then I heard Princess Cyd recommended by Dr. Michele Meek, author of Consent Culture and Teen Films: Adolescent Sexuality in US Movies.

[Princess Cyd is] a little bit under the radar. But it’s a film that depicts a girl’s coming-of-age one summer where she goes to visit her aunt. And she has sexual experiences with a boy and with a kind of gender diverse girl. But the whole thing is really, honestly, presented as very normative and affirming. So you get the idea of the span of gender and sexuality in a way that you just don’t see in a lot of films.

Dr. Michelle Meek

Released April 2023, Consent Culture and Teen Films: Adolescent Sexuality in US Movies by Michele Meek chronicles the history of adolescent sexuality in U.S. films. In looking at contemporary teen films, she demonstrates how even films that take consent into account expose flaws in our affirmative consent framework (particularly how it is highly gendered, heteronormative, and cis-centered) , and she highlights how youth sexuality remains so highly regulated in the U.S. that it is often erased.

Teen films of the 1980s were notorious for treating consent as irrelevant, with scenes of boys spying in girls’ locker rooms and tricking girls into sex. While the film industry now routinely prioritizes consent, ensuring date rape is no longer a joke and girls’ desires are celebrated, sexual consent remains a problematic and often elusive ideal.

Since feminists and queer audiences love this film, I decided to give Princess Cyd another go. This time I persevered, and realised exactly why I would have quit watching after the set-up. Only the trusted recommendations spurred me on.

If you’re an adult watching Princess Cyd with a young person, here are some discussion questions for your consideration.

PRINCESS CYD DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Although Jessie Pinnick played 16-year-old Cyd at around the age of 24, it works. Cyd’s dialogue sounds authentically ‘sixteen’. Give some examples in which Cyd sounds like a real sixteen-year-old, showing herself to be naïve compared to the older adults of the film.

- How would you describe Cyd’s aunt, Miranda Ruth?

- How would you describe the interactions between Cyd and Miranda Ruth at the beginning of the film? And when is the turning point?

- Think back to the opening scenes of Princess Cyd. We meet a sexually explorative 16-year-old girl who is confident in her body and ready for a summer of love. We meet her single and ‘spinster’ aunt who has never moved out of the family home and who doesn’t remember she owns a bathing suit. We also meet a potential love interest for the aunt, and see her examining her body in the mirror. Next, Cyd laughs at her aunt for not having had sex in five years. What story arc would be typical in a romantic drama after such a set up?

- Indiewire.com described Princess Cyd as “a lush film about the joys and limitations of intimacy”. What do you think they mean by “the limitations” of intimacy?

- You’ve probably heard of “compulsory heterosexuality”. What is meant by “compulsory sexuality”? How does the film show how Cyd has, like almost everyone, absorbed cultural expectations of compulsory sexuality?

- This film is recommended as a way to teach consent to young people. Audiences are shown what happens when consent is not sought. (Katie’s storyline at her brother’s apartment.) But the sexual assault subplot is not exactly rare in stories. How else does this original and thought-provoking film explore lesser-understood aspects of consent?

- How does Cyd change over the course of the film? At what point can we see a change has happened?

- Does Miranda Ruth also change? How?

- We don’t see Cyd and Miranda saying goodbye to each other. Instead, there’s a phone call from Miranda after Cyd has returned home, which she receives at soccer training. What do you think lay behind the storytelling decision not to show their goodbye?

CHARACTERISATION OF CYD

A young adult asked me recently as we played doubles tennis together: “Are you a religious person?”

The question came at me out of the blue, but I immediately understood why she asked. I know the conservative religious and political stances of her father. Her older brothers have chosen to stay in the church, one vocationally. This seventeen-year-old is wrestling with which way to go now she’s away at college. Having recently graduated from a conservative, straight-laced local high school, she is researching body piercings, contemplating tattoos. Her politics are more left than her family’s politics.

Older adults rarely ask so directly about religion (sex and politics). With experience, we learn how fraught those questions can be, even when asked out of genuine curiosity. The Internet makes it easier to access a wide range opinions — though actually this fixes nothing. Now we all have access to too many opinions. We still crave the honest opinions of adults in our orbit.

I felt privileged to be asked. This young person obviously cares about my answer, because my answer will help her make a decision for herself.

So when Cyd of Princess Cyd asks her forty-something aunt about her religious beliefs, and then challenges them, I understood exactly why Cyd would be asking. I also understood exactly why the aunt was taken aback, how she might wind up slightly irritated with her niece, but also very mindful of the influential role she is playing in Cyd’s life. To older adults, young adults can come across as brashly naïve, but highly vulnerable in that naivety. They remind us of our own younger selves. We try to be the person we wish we’d had at that age.

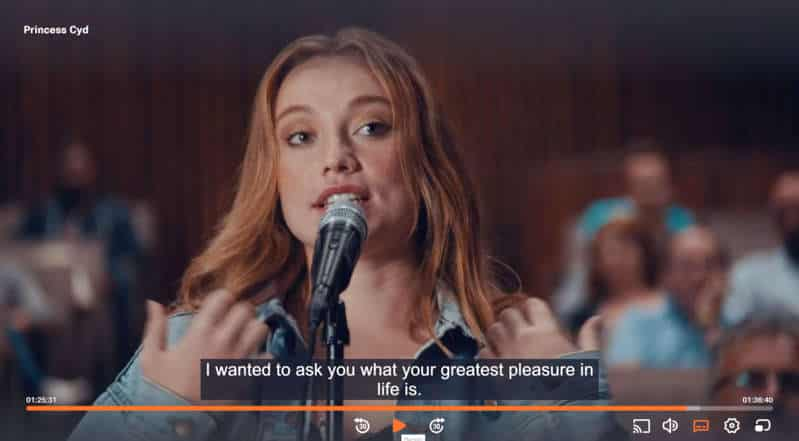

There are numerous examples of Cyd’s brash naivety across most of the film. In fact, she never grows past it. She asks an intrusive sexual question to lesbians she just met at her aunt’s party. She asks another direct question of her aunt at the microphone. The aunt, by this point, sees it coming and has a one-word reply at the ready.

CHARACTERISATION OF MIRANDA RUTH

Miranda Ruth makes a good foil for Cyd in regards to diplomacy because she is the antithesis. We see her welcoming Cyd into her home, and the overly polite awkwardness between them. Miranda Ruth is determined that Cyd feel comfortable. We next see her diplomacy in action when she offers frank but gentle feedback to her journalist/writer friend. She doesn’t hold back in telling the truth, but says it in a palatable way. This is what makes her a good writer as well as a decent human being.

The truth is always something that is told, not something that is known. If there were no speaking or writing, there would be no truth about anything. There would only be what is.

Susan Sontag

Of course, Miranda Ruth knows Cyd’s tragic family backstory before the audience knows, which surely influences her kid-glove interactions. She’s determined to show Cyd a good time in Chicago.

THE AUNT/NIECE RELATIONSHIP

- Cyd questions her aunt’s involvement in the church. When the aunt answers honestly, Cyd dismisses her religious beliefs by referencing her dead mother as evidence of no life beyond death. She’s playing a trump card here, or thinks she is. She silences her aunt, who knows about Cyd’s childhood trauma.

- Cyd convinces her aunt to lay out in the yard with her, quietly accusing her of being too prudish to do such a thing. But the aunt is working to build a strong relationship with her motherless niece, so takes Cyd’s lead and joins her. Now Cyd launches into an inquisition about Miranda Ruth’s sex life.

- The turning point comes in the kitchen as Cyd makes a small effort to help her aunt clean up after the Friday night lit party. Cyd earlier walked out of the room for a very obvious sexual encounter with another young man, just as Miranda Ruth was reading her chosen piece. Miranda Ruth is wrestling with the tightrope of teaching Cyd basic human consideration while also wishing to avoid anything which might be taken for sex shaming.

- But Cyd doesn’t suddenly grow up after the kitchen speech. When Katie finds Miranda Ruth’s book titled Princess Cyd on the shelf, Cyd’s self-centredness shines through when she asks her aunt why she named a book after her. “Check the date,” Miranda tells her. Of course, the book existed before Cyd existed, but Cyd can’t fathom a world which existed before she came into the world. The imaginative leap is just a little too far. Basically, Cyd must learn to develop her imaginative powers, which includes insight into how others experience the world differently. Imagination is required before understanding that people have different needs and desires, sexually or otherwise.

- We do see Cyd’s epiphany. Brash as always, she is questioning her aunt at the microphone. Making light fun of the situation, she takes the floor and asks her aunt about her greatest pleasure in life. The aunt’s answer is the perfect ace easter egg. (If the cake reply isn’t an asexual community reference, this is the most accidental ace line I’ve ever heard on screen.) Right after that, Cyd looks beaten, but then a slow smile crosses her face. The one word reply of ‘cake’ takes Cyd back to a lengthy speech in the kitchen and she gets it now. People are different. And differences are not to be interrogated. The audience stands in for ‘society at large’ and ‘societal expectation’. We should all interrogate societal expectations, and how they have informed our own expectations and desires.

WHICH PLOT DOES THIS FILM SUBVERT?

The plot of Princess Cyd avoids the story of a lonely spinster who learns to embrace life by finding romance and sex, enlightened by her sexually liberated younger relative. Almost every love story ends with characters partnered off, to the point where offering specific examples is fruitless.

But I will give a few examples of stories which could so easily have been done differently.

The first which springs to mind is Shrek, which aims to subvert the idea that you have to be beautiful if you want to find love. (The franchise is significantly different from the original picture book.) I don’t believe Shrek is a subversive story at all. The main message ends up being: Know your level. (If you’re ugly, there’s another ugly creature out there who will still have you.) A truly subversive Shrek would end at the part where Fiona and Shrek each realise that there are more options in life than (heterosexual) marriage, and that happiness lies in finding your people and passion. Of course, this was way too wild for the turn of the millennium, before amatonormativity was even a word. (Amatonormativity was invented by Elisabeth Brake in 2011.)

I’m old enough to remember when Friends aired live in the decade between 1994 and 2004. Across ten seasons, Friends appeared to be a celebration of singledom and, as the title suggests, of friendship. Even in 2004, before the hoardes of allocishet Friends fans were cognizant of polycules and QPRs (queer platonic relationships), many expressed disappointment in the decision to pair off the characters into run-of-the-mill marriages. Was that the best they could do? Must happy endings look like that?

In mainstream storytelling, little has changed since then. In the vast majority of stories, happy endings look like romantic pairings. The only thing that has changed: We now see same sex romantic pairings as well as straight ones.

We far less often see single, well-adjusted adults who take delight in the romantic and sexual explorations of those around them and who are happy to remain single themselves, fulfilled by their friendships, hobbies and vocations. Miranda Ruth is a wonderful rare example of that person in fiction. Yet she is not at all rare in real life. You probably know a few Miranda Ruths.

COMPULSORY SEXUALITY AND THE LIMITATIONS OF INTIMACY

Compulsory HETEROsexuality was popularized by Adrienne Rich* in her 1980 essay titled “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence”. According to Rich, social science and literature perpetuate the societal belief that women in every culture are believed to have an innate preference for romantic and sexual relationships with men.

Compulsory sexuality (without the hetero) is a newer term which riffs on Rich’s concept. Ideas around compulsory sexuality come mainly from the asexual community, who recognise the pervasive cultural assumption—set into relief by the emergence of asexuality and popular responses to it—that everyone is defined by some kind of sexual attraction. (Not true.)

However, compulsory sexuality does not just affect the asexual community. These expectations affect everybody. We all receive the cultural conditioning that to be a sexual being is to be human. This expectation perpetuates insecurity: Am I having enough sex? Is the sex I’m having good enough? Should I be doing/having/receiving more? Early 2000s feminism unfortunately contributed to the idea that, to be a Good Feminist, women must know what they want sexually, then nurture the confidence to proactively get it. This expectation holds even when liberally minded women don’t necessarily want partnered sex, or any sex at all. In conservative circles, sexuality becomes compulsory post-marriage, which presents a different but entirely related set of problems. For men everywhere, sex is a prerequisite to adult masculinity. For many (allosexual) queer people, sex is a huge part of identity. Gay spaces don’t necessarily make room for those who do not appear sufficiently liberal and open to sex.

Everything you know about sex and asexuality is (probably) wrong.

The notion that everyone wants sex–and that we all have to have it–is false. It’s intertwined with our ideas about capitalism, race, gender, and queerness. And it impacts the most marginalized among us. For asexual folks, it means that ace and A-spec identity is often defined by a queerness that’s not queer enough , seen through a lens of perceived lack of pleasure, connection, joy, maturity, and even humanity.

In this exploration of what it means to be Black and asexual in America today, Sherronda J. Brown offers new perspectives on asexuality. She takes an incisive look at how anti-Blackness, white supremacy, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and capitalism enact harm against asexual people, contextualizing acephobia within a racial framework in the first book of its kind. Brown advocates for the “A” in LGBTQIA+, affirming that to be asexual is to be queer–despite the gatekeeping and denial that often says otherwise.

CONSENT

The likelihood of sexual coercion–and sexual violence–is elevated for everyone who has not yet learned about compulsory sexuality, a presence that is rarely challenged.

[…]

Every no is good enough, and that goes for every person. If we believe that people shouldn’t have unwanted sex with strangers and that strangers are not entitled to sex, we should believe that people shouldn’t have unwanted sex with partners and that partners, no matter how loving or good, are not entitled to sex either. As long as people don’t know about asexuality — hell, forget about the label, so long as they don’t know that saying no forever and for any reason and in any context is okay–sex education, sex therapy, and popular depictions of sex are incomplete and people don’t have the relevant information to fully consent.

Angela Chen: Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex (2020)

Note that Angela Chen includes ‘popular depictions of sex’ in that list. Film is especially influential, which I presume is why Dr Dr. Michele Meek wrote Consent Culture and Teen Films: Adolescent Sexuality in US Movies. We need to see more characters on screen not having sex, and being fine with it.

As it happens, I don’t read Miranda Ruth as asexual. She may resonate with grey asexual viewers, but I believe she is canonically a cisallo straight woman who is experiencing the common vicissitudes of sexual desire which, for allosexuals especially, wax and wane over the course of a lifetime. For Cyd, who has only just discovered sex and who approaches it with the fervour of a born-again Christian spreading the Gospel, sex is the centre of her life right now. It’s likely that sex was far more central to Miranda Ruth’s life once, and it may be again someday. But right now, sex is not central or even peripheral to the aunt’s life. And by avoiding the bog standard romantic pairing for Miranda Ruth, audiences see — indirectly — that consent to sex is no such thing unless there remains the right to not have sex with anyone at all.

The asexual community is very articulate on this point, though others are saying similar things in parallel, e.g. writers like Amia Srinivasan, who wrote a book of essays called The Right To Sex, which broadens the conversation to question contemporary cultural conversations regarding consent in the context of p.orn and sex work:

Sex is no longer morally problematic or unproblematic: it is instead merely wanted or unwanted. In this sense, the norms of sex are like the norms of capitalist free exchange. What matters is not what conditions that give rise to the dynamics of supply and demand — while some people need to sell their labour while others buy it — but only that both buyer and seller have agreed to the transfer.

Amia Srinivasan, The Right To Sex, 2021 p82.

The acknowledgement that capitalism affects every part of life expands the conversation which needs to take place around the problematically binary ‘affirmative consent’ model, which doesn’t work for (sexually active) asexuals and doesn’t work for sex workers either, alongside everyone else. Sexual consent is not binary, is not always ‘enthusiastic’ and doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

Princess Cyd only touches the side of this issue, but Miranda Ruth’s kitchen speech to Cyd shows audiences very clearly that one can lead a happy, fulfilling life surrounded by people who love you, even without sexual intimacy. This is not a message anyone is getting in large doses, whether conservative, liberal or somewhere in between. Before we even ask ourselves, “What kind of sex do I want, and with whom?” the first question should be, “Do I want any sex at this point in my life? If I don’t have sex, do I believe this will make me a lesser person?”

If the answer to that last question is yes, ‘consent’ to sex is muddied.

CYD’S CHARACTER ARC

Cyd’s coming-of-age arc is mostly a sexual awakening. But beyond the discovery that she’s interested in girls as well as boys, and beyond the more practical aspects of sex, she learns from her aunt that sex is great, but it is not the be-all and end-all, not for everyone, and not at every life stage.

Initially, Cyd positions herself as matchmaker, like a modern Emma (cf. Jane Austen). She assumes her aunt to be repressed and lonely. First she questions her aunt about the handsome journalist friend, then she awkwardly interrogates the journalist friend himself.

More broadly, Cyd will learn that people are different, and we must respect each other’s differences. Sometimes, this means learning to mind your own business.

MIRANDA RUTH’S CHARACTER ARC

Miranda Ruth is surrounded by found family, but her sister has died young (and we can assume also the parents). She is unused to forging a relationship with a family member. This is new for her. She isn’t new to interacting with young people, as a professor at a nearby college. But this is high stakes.

Is this a double character arc? Does Miranda Ruth learn anything from Cyd?

I believe she does. As a reflective person, Miranda’s interactions with the brash young niece cause her to reflect on her own values and morals. All parents of teenagers go through this same thing. Where do we stand on drugs? Perhaps we’re okay with others smoking pot, but where do we draw the line? Miranda seems to realise for the first time that she draws the line at teenagers smoking pot inside her own house.

Many (most?) of Miranda’s friends are queer. But where does she stand regarding her sixteen-year-old niece having sex with a boy and a girl (separately but concurrently) under her own roof? She decides she will be fine with that part. No one has made anyone any promises; this is Cyd exploring her sexuality over a very short, two-week period. Everyone involved knows this.

In this way, Miranda is forced to face moral issues which were perhaps a little hazy before.

I also sense that Miranda has achieved the next level of self-acceptance via Cyd’s interrogation into her sex life. In the moment, Miranda appears almost ashamed that it has been so long since her last partnered encounter. She takes Cyd’s lead in this shame. Keen to forge a relationship with her high school-aged niece, she momentarily slips into the very high-school mindset that if you’re not having frequent sexual encounters, you should be somewhat ashamed of yourself. This, apparently, says something about you, and your overall desirability.

But later, when we hear Miranda’s speech in the kitchen, we know she has given that conversation great thought. She has no doubt chided herself for falling into the trap of thinking there might be something wrong with her for ‘failing’ to have a romantic partner. She knows she is happy as she is, so why slip into the shame, even in jest? If she weren’t happy, she would have done something to change her romantic situation. This needs to be a teaching moment.

THE ENDING

The final phone conversation shows us that after the compressed and intense two-week parenting experience, Miranda has developed affection for her niece and would love to continue in her mentor role. Audiences can extrapolate that Cyd will be joining Aunt Miranda in Chicago when she graduates high school, and the pair will continue to challenge each other, strengthening their familial bond.

Significant events in real life don’t always need to be turned into a scene for fiction. Goodbyes are one example. Unless the story is about goodbyes, a goodbye scene may not be necessary. Likewise, unless the story is a road trip story, we don’t need to see characters driving from point A to point B. Unless the story is a classic romance, we don’t necessarily need to see the wedding day.

We don’t see Miranda and Cyd say goodbye because this two weeks marks the start of a relationship, not the end. Apart from that, we know how it would have played out. “Thank you so much, Aunt Miranda! I’ll see you again soon! Make sure you keep in touch, now” etc.

More importantly for the messaging in this particular story, it’s vital that we see the interaction between Aunt Miranda and her journalist man-friend, who has met a potential love interest. Audiences should know by now not to try and read Miranda’s face when he confirms interest in a neighbour. Miranda’s love life — or lack thereof — is her own business, and so it’s important we are left with ambiguity. Will they or won’t they? Who cares? Does it really matter? We have seen that Miranda is fulfilled and well-rounded. She doesn’t need a romantic partner to complete her.

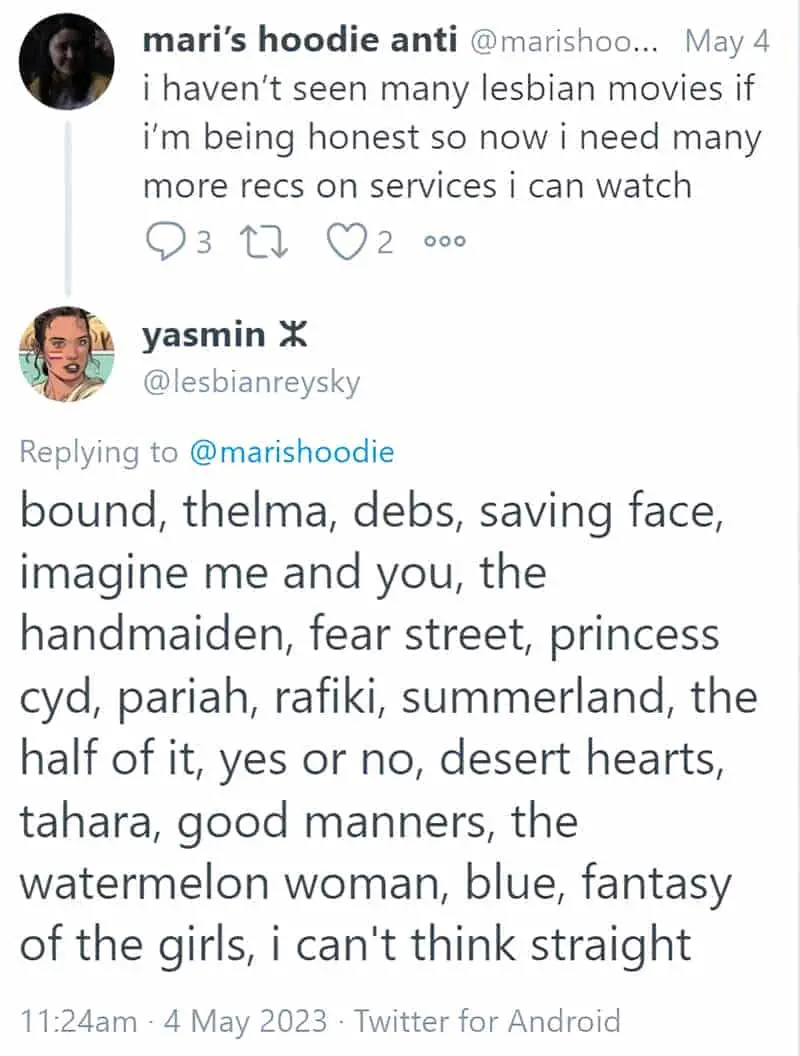

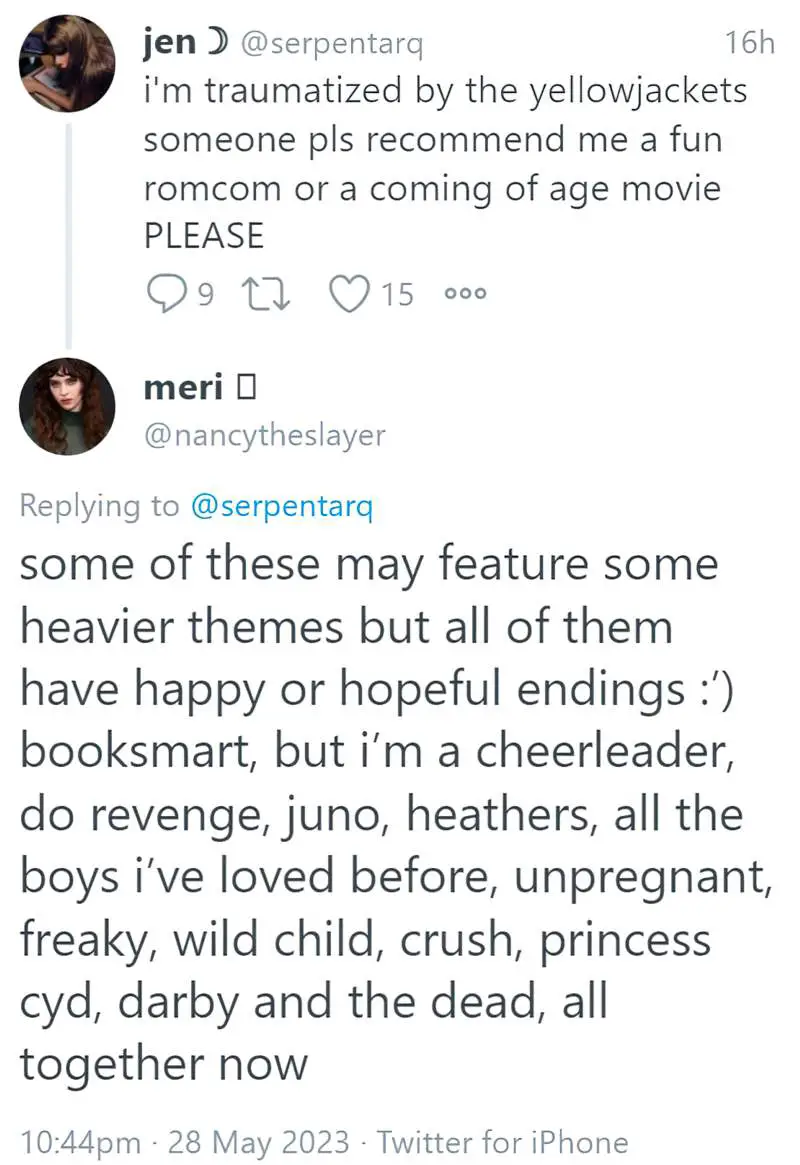

SIMILAR FILMS TO PRINCESS CYD

Princess Cyd is most frequently found on lists of films featuring lesbian love matches, rather than films about nieces and their aunts. But if you’re looking for films about young women and their mother figures, I highly recommend Lady Bird.

*So I quoted Adrienne Rich

what I’m trying to tell you is that there’s a very influential book that argues for the “mandating” trans people “out of existence” (verbatim) and that this book was edited by Adrienne Rich

what I am not telling you is that Adrienne Rich is a “complicated figure.” this is not some Gloria Steinem apologizing blandly in the 2010s type situation. what I am telling you is that Adrienne Rich edited a book that calls for the mandating of trans people out of existence

what I am telling you is that this book has had enormous consequences for trans people, particularly trans women, particularly in north america and the UK

I live in a poetry community where you mention her name to me and you don’t mention this

I live in a poetry community where you mention her name in public where you know I sometimes am and you do not mention this

and yes, you are right, she is a “complicated figure.” I also enjoy the poetry and have been influenced by the thought of Adrienne Rich

we would like to talk about Adrienne Rich. you are a feminist poet, or a feminist critic, and you have an investments in what is called “feminist thought.” but somehow, you are concerned only w rehabilitation. you have no interest in accounting for The Transsexual Empire.

this is not a part of your feminist project

so if I have ever seemed, at times, a little too angry, paranoid, or resentful, it is because you mentioned, in front of me, sometimes to me, many times, many times, a woman who had edited a book that says I should be mandated out of existence

and you did not mention that fact, and many times you did not know it, and when I told you you became upset, and I comforted you

so I live on another planet from you I guess, and I will not be meeting you, because how can I? how can I do what you’ve asked of me? if I did what you are asking of me, I’d go mad from a deficit of dignity

@supermattachine, Stephen Ira, who wrote a poem about this.