What does it mean to be human? Dancing, music, love, sex, cooking, other people… You’ll have heard these answers. Many are problematic.

We’ll talk about ‘what makes us human’ and say it must be ‘language’ or ’empathy’ or ‘culture’ or ‘the capacity for thought’ or ‘the need for stories’ — I could go on. The problem is that every single definition leaves some human beings out, and, as I’ve said again and again, when you are dehumanized, left outside the fold of the first person plural, then you are in danger — of social death, and also of the absolute, physical kind.

Joanne Limburg, Letters To My Weird Sisters, 2023

EXPANDING THE QUESTION

First, this question has various answers depending on context:

- What does it mean to be human and not some completely different animal?

- What does it mean to be genus Homo compared to some other human-like species which came before or branched off?

- What does it mean to live a decent life?

NUMBER ONE: HUMANS COMPARED TO OTHER ANIMALS IN GENERAL

Brian Christian: Philosophers from Descartes all the way back to Aristotle have grappled with this question of what makes human beings special and unique. They approached it largely by writing off everything that other animals can do. We’ve seen in the animal rights movement starting approximately with Peter Singer in the 1970s a much more developed appreciation for just how complex the inner life of many animals really is.

So that was something the philosophers had wrong for about two and a half millennia. We’re only now just coming around. So I think having that same modesty about our claims [about what makes us human] is very important.

Kim Hill: Yeah. What’s it like to be a bat? What’s it like to be a large language model chat box.

Brian Christian: [Laughs] Exactly.

“Brian Christian: how would we know if AI becomes conscious?”, RNZ, Saturday Morning With Kim Hill, Saturday 2 September 2023

The more we learn about animals, the more we realise humans aren’t so unique. This has been happening over centuries and only goes in one direction. At no point do scientists study an animal and find it less complex, less interesting, than previously thought.

The ability to think abstractly about other minds is singled out by many as a uniquely human trait. Now, a study from the Universities of Houston and Vienna have found that ravens are able to adapt their behaviour by attributing their perceptions to others.

Ravens have paranoid, abstract thoughts about other minds, Wired

NUMBER TWO: WHAT MAKES HOMO SAPIENS DIFFERENT FROM SIMILAR SPECIES?

The conversation below exemplifies how difficult it is to determine ‘what makes a species’, and also how the definition changes with scientific advances:

Q: How do we describe the modern human?

A: Right. I didn’t want to put Modern Human in the title because I was scared people would approach it and not know what the book was about. Some people might think it’s about people in the 1950s. An historian might think the book is about people in the sixteenth century. And so I wanted the title Cro-Magnon. No one calls early humans in Europe Cro-Magnon anymore. But I knew the term would be instantly recognisable and people would know I’m talking about human evolution.

I use ‘modern human’ as just a shorthand for homo sapiens, our species. … I discuss how Chris Stringer (the paleo anthropologist) thinks that … the oldest potential [archaeological evidence] of our species is not ‘modern’ in his anatomy. I agree with him. It lacks a lot of features … present in people today. But he does think it’s a member of our species of homo sapiens. The earliest specimens are from Africa. Interestingly, they’re from all over Africa. So if we were conducting this interview, say, 20 years ago, and we were advocates for the African Origin model, we might say, Oh

modern humanity emerged in one spot: East Africa, you know, 100 thousand years ago and then spread to the rest of the world.

The view is a little more complicated now because it looks like we have gene flow, or exchange of genes of different populations across the African continent early on. Some researchers have taken to calling the recent African Origin model ‘African Multi-regionalism’ [but] I don’t want to use that term in my book because I don’t want it to be confused with multi-regionalism in general.

But modern humanity emerges in Africa. It’s a separate species but I don’t think that means we’re reproductively isolated. No one does anymore.

Reproductive isolation is an idea that dates back to Ernst Mayr (pronounced: My-ar). He defined species as groups reproductively isolated from other such populations. When you can see it, [reproductive isolation] defines populations pretty well. Horses and donkeys are members of the same genus but they interbreed to produce mules, for example. Mules tend to not be able to reproduce themselves and as a result horses and donkeys are reproductively isolated from each other. They’re two separate populations.

But biology is really messy … and there are groups I think are separate species but nonetheless retain the ability to interbreed with each other. We know from ancient DNA that Neanderthals and Early Modern humans interbred with each other successfully, and that most people around the world today carry at least some Neanderthal genes.

Trenton W. Holliday, Cro-Magnon: The Story of the Last Ice Age People of Europe (Columbia UP, 2023) episode published Monday 23 October 2023, New Books Network

NUMBER THREE: LEADING A DECENT LIFE

Being human means yearning for more than subsistence. As much as food or shelter, we require hope.

[…]

During one long reporting trip, I had to get a prescription refilled. My doctor called a drugstore. Later he told me that, when the pharmacist demanded my home address, he didn’t know how to answer and blurted out, “She’s living in a van!” The pharmacist let it slide, but the episode made me think. In America, if you don’t have an address, you’re not a real person.

Jessica Bruder, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century

Much of the time, though, ‘what it means to be human’ feels like another way of exploring ‘what it means to feel alive’ or ‘what it means to live a meaningful life’.

…being solitary for a long time and fully attuned to the natural world means risking everything human.

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

To be human we need to experience the end of the world. We need to lose the world, to lose a world, and to discover that there is more than one world and that the world isn’t what we think it is. Without that, we know nothing about the mortality and immortality that we carry. We don’t know that we’re alive as long as we haven’t encountered death: these are the banalities that have been erased. And it is an act of grace.

Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing

The same author understands that humans are far more built for alone time than we modern-times dwellers commonly think:

Our genus, Homo, arose two and a half million years ago, and for more than ninety-nine percent of human existence, we all lived like Onwas, in small bands of nomadic hunter-gatherers. Though the groups may have been tight-knit and communal, nearly everyone, anthropologists conjecture, spent significant parts of their lives surrounded by quiet, either alone or with a few others, foraging for edible plants and stalking prey in the wild. This is who we truly are. The agricultural revolution began twelve thousand years ago, in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, and the planet was swiftly reorganized into villages and cities and nations, and soon the average person spent virtually no time alone at all. To a thin but steady stream of people, this was unacceptable, so they escaped. Recorded history extends back five thousand years, and for as long as humans have been writing, we have been writing about hermits. It’s a primal fascination. Chinese texts etched on animal bones, as well as the clay tablets containing the Epic of Gilgamesh, a poem from Mesopotamia dating to around 2000 B.C., refer to shamans or wild men residing alone in the woods.

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

PROBLEM ANSWER 1: ANTHROPOCENTRICITY

Anthropocentrism is the idea that humans are at the centre of everything on Earth, and that other species exist only to serve and validate us.

Anthropocentrism also gives rise to the idea that humans are superior to other animals. Our own kind of intelligence becomes the very definition of intelligence. And despite all evidence to the contrary, humans are seen as the only species capable of acting morally.

Tropical birds dance. Arguably, most birds are better than most humans at making music. And anyone who has lived alongside a pet dog will know for sure that animals are capable of love. For all we know, some animals love in a way that is more pure than human love.

But there’s more to it than that. The first issue is that humans didn’t branch off from other species because of our amazing ability to walk on two legs and invent language. We branched off because our genes co-evolved with pathogens.

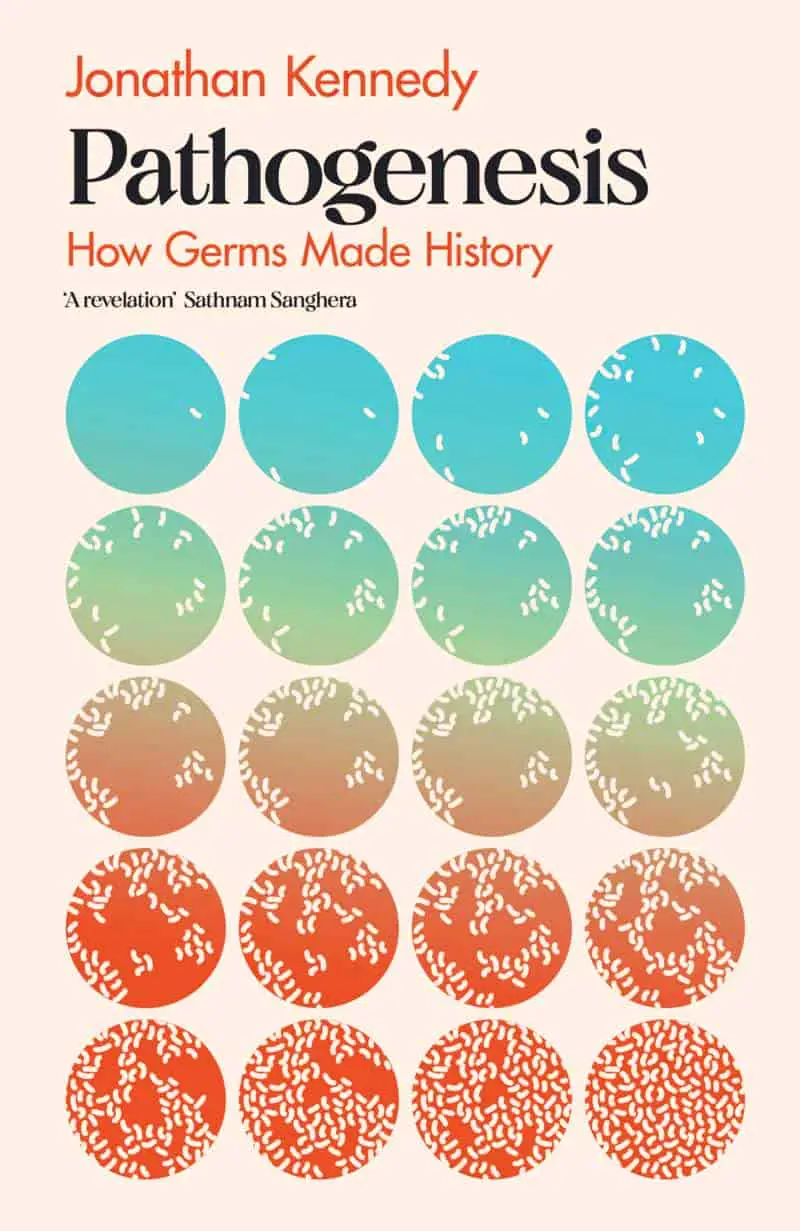

Riffing on Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Jonathan Kennedy’s own description of his book Pathogenesis: How Germs Made History could be titled Germs, Germs and Germs.

By confronting our ongoing battle with infectious diseases globally, Dr Jonathan Kennedy shows how germs have been responsible for some of the seismic revolutions in human history, and how the crises they precipitate offer vital opportunities to change course.

marketing copy

Jonathan Kennedy makes the case that it’s not what humans have done and achieved which separates us from other species, but it is simply our interaction with microbes which led directly to where we are today at the top of the food chain. It’s not because Homo sapiens “out thought” the Neanderthals. It’s because we co-evolved with germs.

[Germs have played a critical role in human evolution] when we think that complex life evolved from single-celled organism that were either bacteria or pretty much like bacteria. The first complex cells emerged when two of these single cells came together and started living in a symbiotic union, which is why, for example, mitochondrial DNA is different from the DNA in our cell nucleus. […] Eight per cent of our DNA comes from these retrovirus infections. They’ve allowed us the ability to perform all sorts of functions that we think of as fundamentally human. But even today, the bacteria in our body are influencing things like our moods, which fundamentally questions what it means to be human. […] If microbes have played such a vital role in our individual bodies, what role do they play when we look at aggregations of bodies (society)? [What happens] when we look at the body politic, the body social and the body economic?

Interviewer: Germs make up 30% of the genetic difference between chimps and us.

When we think of this, it fundamentally alters the way we understand evolution. If we think of Darwinian evolution by natural selection, there’s this idea that you have this big struggle between various species and within various species, and the biggest, strongest, smartest survive. This is the driving force of history. Nature is ‘red in tooth and claw’, as Alfred Lord Tennyson said. Brutal competition is going on between and within species. […] The economics of Adam Smith had a big influence on Charles Darwin. We can almost see this theory of evolution is basically classical economics as applied to the natural world. But when we actually look at the nature of evolution, when scientists have done this over the last few decades, we see it’s not so simple. Where there is competition, often it’s not within species and it’s not competition with apex predators. The biggest driver of evolution is infectious diseases. Therefore, one of the biggest factors that allows people to survive and pass on their genes is their ability to survive infectious diseases and pandemics. […] About a third of genes were selected for because of viral infections.

[…]

Often there’s these really miraculous events that happen in history. They’re kind of hard to explain unless you refer to the role of infectious diseases. […]

The dominant explanation is that Homo sapiens were more intelligent and because of this we were able to out-compete Neandertals. But there’s been a variety of recent research that’s demonstrated Neandertals were capable of all sorts of sophisticated behaviours. We’ve got to the point now where the gap between Homo sapiens on the one hand and Neandertals on the other, in terms of behaviour, is absolutely tiny.

For example, Neandertals were able to sail between islands in the Eastern Mediterranean. They certainly knew how to use fire. They painted basic images onto cave walls. They also appear to have used various medicinal plants to treat maladies. So this explanation that Homo sapiens — which of course means ‘wise man’, or ‘wise humans’ — were more intelligent than Neandertals [is wrong]. One hundred years ago people were calling Neandertals “Homo stupidus”. This Homo sapiens/Homo stupidus dichotomy is no longer viable, so this raises the question, what actually happened?

We should remember that Neandertals were also bigger, stronger and heavier than Homo sapiens. So this adds to the mystery. The most convincing explanation is infectious diseases. For at least five hundred thousand years Homo sapiens were living in Africa and Neandertals were living in Western Eurasia. They occupied a pretty large area all the way from Gibraltar in the West to the Altai mountains in Siberia. We were evolving in different parts of the world with different climates and also different disease environments. Certainly there’s no evidence that we interacted for hundreds of thousands of years. But then, maybe 120-150 thousand years ago we have evidence that humans began to interact with Neandertals. We were pushing out of Africa into the Levant [Middle East], and Neandertals were pushing down from Western Eurasia. We know the two species of human met because…people whose ancestors grew up in Europe, in Asia, or Native Americans have somewhere between 2 and 4% Neandertal DNA. This comes from these liaisons that occurred 60-100 thousand years ago.

The really important thing to remember is that these genes we’ve inherited from Neandertals, they’re not random. We retain certain gene variance because they gave us an advantage as we pushed out of tropical Africa and into more temperate Eurasia where there was a different disease environment. We also have to think what would happen when we first met. Clearly species had sex and reproduced, but also we would have exchanged infectious diseases that would’ve had a pretty insignificant impact on the species that were carrying them, because they’d evolved to deal with them. But the other species meeting these pathogens for the first time would have been absolutely devastated.

[…]

The classic explanation [of why certain humans conquered other humans, as explained earlier by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs and Steel] is critiqued in the book. Diamond argues that as Europeans conquered other parts of the world because we had better technology, but also we were helped along by our germs. When you read Diamond’s book he says the technological advantages Europeans had over Americans were so big that we would have conquered the continent anyway. But we have to realise that, actually, it’s really hard to conquer a foreign country or community that doesn’t want you there. It’s really hard to cross an ocean and impose yourself upon another society. We’ve seen that in the last twenty years with what’s happened in Afghanistan. The Americans and their allies had pretty modest aims, to change the regime. They threw enormous amounts of resources at the problem as they saw it, over a hundred thousand troops at the height, trillions of dollars spent on the most advanced arms ever used in warfare against what was essentially a pretty ragtag book of religiously infused servants. [But America] was no better off after 20 years than they were at the beginning. [This] shows how astounding the Spanish conquest of the Americas was.

The Future of Germs: A Discussion with Jonathan Kennedy at the New Books in History podcast.

The second issue with the “our smarts makes us human” argument: If evoking specific technologies as evidence of our humanity, the tech we choose is subject to cognitive bias. Most of us think of the same few technologies when it comes to boasting human achievements, and forget the many, many others, which we didn’t so much as ‘invent’, but ‘utilise as they came along’:

Creative products without apparent merit, value or utility, but with the power to transform life given enough time, are everywhere, in nature and culture. […] Creating successfully is beyond hard. It is outside the creator’s control.

Sleeping beauties: the evolutionary innovations that wait millions of years to come good

Raymond Tallis echoes the role of “biological luck” in the rise of Homo sapiens, and adds that the rate at which we are diverging from the rest of the natural world is accelerating greatly of late. For Tallis, ‘what makes us human’ is ‘shared consciousness’:

How did we get ourselves so distant from biology? We must have some kind of biological explanation. And there’s all sorts of Just So stories that you could write […] that gives priority to the hand, the upright position, predominance of vision, and ultimately, language. But language is […] a recent arrival. Who knows, forty thousand, one hundred thousand, three hundred thousand years ago. But actually, we were already very different [from every other biological thing in nature] a million years ago. I’ve talked a lot about early tools, axes, pebble choppers [primitive tools] and so on. So the means by which we came to be so different was a bit of biological luck. Then we built on that.

But that process of our becoming different has accelerated enormously in the last, well, one hundred thousand or three hundred thousand years, and particularly in the last thousand years, and particularly in the last hundred years, especially the last ten or twenty years.

One of the keys to our becoming more and more distant from nature, more able to manipulate it, is our ability for us to share our consciousness in an explicit way. Human consciousness is woven out of joined intentionality. And you can see that present very early on in the lives of human beings. […] Those of us who’ve had babies know that […] at least a month or two before language emerges, the child is communicating by means of pointing. It’s sharing its experiences, pointing to a human universal and it’s unique to humans, at least so called ‘declarative pointing’ is. That ability to share our experiences, to acknowledge a common or shared world, to create a public sphere is central to the process by which we gradually become more and more distant from nature.

What it means to be human with Raymond Tallis at Philosophy For Our Times

PROBLEM ANSWER 2: ABLEISM

If ‘dancing makes us human’, what does that mean for people who cannot physically dance? Before we expand our definition of ‘dancing’, no, not everyone can dance.

And not every human points. Raymond Tallis isn’t talking about individuals when he says ‘declarative pointing is unique to humans’. It’s a little more problematic that he says declarative (deictic) pointing is ‘a human universal’, because this is simply not true. It is true for neurotypical, able bodied humans. It is not always true for autistic children.

children with autism produced fewer index finger pointing gestures and fewer no contact pointing gestures than typical controls. This difference in the nature of the gestures produced by the children with autism is thus indicative of a qualitative difference in gesture production.

Different Ways of Making a Point: A Study of Gestural Communication in Typical and Atypical Early Development

(This is not a deficit, but a neurodifference.)

And if “talking” is “part of what makes us human” does it follow that if someone does not talk, then they are less human?

We are social animals and talking is part of what makes us human.

from the marketing copy of Talking Heads: The New Science of How Conversation Shapes Our Worlds by Shane O’Mara

See also: The difference between ‘non-verbal’ and ‘non-speaking’. Definitely worth looking up since the language has shifted over the past decade or so. “The term nonverbal is stigmatized because the general population equates nonverbal to not having or receptively understanding language.”

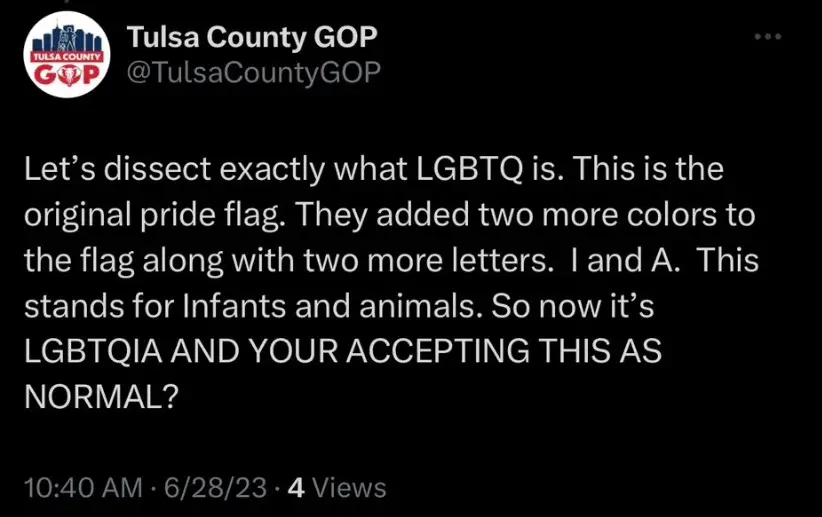

PROBLEM ANSWER 3: ACEPHOBIA

- “Sex is what makes us human.”

- “All humans need sex.”

- “Humans are sexual creatures.”

EXAMPLES OF “SEX MAKES US HUMAN” STATEMENTS

Sometimes it looks like this:

Even in 2023, autistic advocates are writing things like this in books:

People have retrospectively applied tentative diagnoses to their entire ancestry in response to discovering their own autism, based on their memory of how many autistic traits their grandparents, great-aunts and uncles and distant cousins have. It’s often, it seems, a family affair. Now, none of this would be the case if autistic people weren’t having sex.

Autistic people are human, and like all human beings the majority of us have the desire to enter romantic and sexual relationships. Autism does not strip us of that basic human need. Admittedly, there are plenty of aromantic and asexual people in the autistic community, but then this is true in the neurotypical community too. Autistic people date, and flirt, and sleep around, and settle down, and marry, and divorce. It’s just something that’s rarely discussed or considered by the wider public…

Pete Wharmby, Untypical, 2023

Pete Wharmby is committing some basic errors here, as an allosexual autistic. By writing the phrase ‘autistic people are human’, given the context, he makes the classic mistake of conflating sexuality with ‘being human’. This is classic compulsory sexuality.

The rest of the sentence makes no sense due to the two competing phrases ‘all human beings’ and ‘the majority of us’. Is it all, or is it the majority, Pete? (Hint: It’s the latter.)

His subsequent disclaimer about there being asexual people in the autistic community feels like a reluctant add-on. The part where he suggests asexual people exist in the neurotypical community at about the same rate as in the autistic community is also just plain wrong, as if this is an attempt to divorce his own autistic identity from asexuality entirely. “Admittedly” carries freight. Imagine saying “Admittedly, there are people of colour in the autistic community”, or “Admittedly, there are transgender people in the autistic community”. How does that sound? Does that sound wrong? Because it really should. There’s no solidarity in this book.

“Sex is essential to humans! It’s vital to mental & physical health-more important than love! (but some people are asexual)” Misses the point entirely. You shouldn’t expect Aces to be happy with a half-hearted shoutout while you’re repeating the same rhetoric that marginalizes us

The Ace Couple on Twitter 12:46pm · 31 Mar 2023

In the replies:

This is why ace inclusion is too small of a goal. Destroying amatonormativity and seeking collective liberation is the only way out of the toxicity we have built around sex. Sexual liberation rejects these mandates in favor of knowing and respecting our bodies, needs, and desires

Jenna De Witt

Another example of ace invisibility and acephobia comes from an own voices autistic advocate and author Michael John Carley, who writes specifically about sex for the autistic community. His third book, The Book of Happy, Positive, and Confident Sex for Adults on the Autism Spectrum…and Beyond! (2021) does a lot of things right, and has been hailed by reviewers as the most “LGBTQ plus” sex guide of its kind. The illustrator is gay, the bodies are diverse (in skin color, size and age), and the author is trans positive, sex work positive, polyamory positive, po*n positive. (I can’t write that word on my blog and still serve ads.) This American author is clearly driven by a terrible history of autistic desexualisation which, when coupled with conservative right-wing sex negative culture, has resulted in a huge fear around sex for many, especially for Autistic people.

However, an “LGBTQ plus” positive book is no such thing when it erases the humanity of asexual Autistics (many of whom are also trans non-binary). In a podcast interview (at the ironically named Uniquely Human podcast), Michael John Carley opens with the following red flag:

I would hope everybody says this about themselves: I love it [sex]. I cherish it. It is a part of life that is I think one of the most beautiful things that we are all going to be able to experience, no matter what relationship structure we choose.

Uniquely Human Podcast Friday 16 April 2021

Here’s what Michael John Carley fails to understand: The very culture which created the sex negativity he eschews is the very same culture which (again, ironically) makes sex compulsory for everyone, regardless of orientation. This is hugely damaging to asexual people. Try being Evangelical Christian, or any other major religion, and also asexual. Are you allowed to be yourself? Hell no. There are many, many testimonies from asexual people with conservative Christian backgrounds who are as sexually traumatised by the far right as the allosexuals are. The Ace Couple made an excellent episode on that, and continue to speak intelligently about the issue.

SEX IS HARDLY UNIQUE TO HUMANS

First, sexual reproduction was happening long, long before humans popped in. If sex makes us human than flowering plants are also human.

But let’s take it in good faith and assume that “Sex makes us human” is actually short for “loving (partnered) sexual acts” make us human. Even then, an African safari tour during lion mating season will offer a spectacle of just that, and no one is arguing that lions are human. Fortunately, lions don’t care what we think of them.

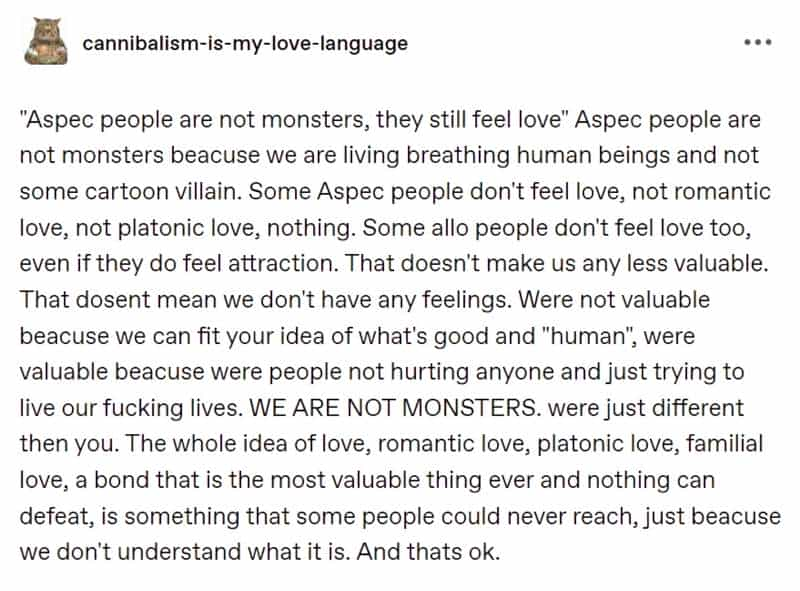

More problematically, there is a large community of very human humans who are affected by this othering language, because not everyone seeks, needs and desires sex. Many in the asexual community are routinely dehumanised by such language, which is everywhere. “Sex is what makes us human” is a prime example of a microaggression. It often comes from within the queer community, and frequently comes from people who have fought hard to reclaim their own sexual identities and sex lives in a culture which makes sexual freedom a hard-won battle.

Part of the reason for this thinking comes from misapplied historical psychology. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs shoulders much of that blame, but let’s not blame Maslow himself. Maslow never made his complex ideas into a pyramid. Instead, the pyramid came from a management textbook publisher who thought business students wouldn’t understand nuance. There’s an apocryphal story that Maslow once saw the pyramid diagram and asked what it was.

So what did Maslow think about sex, and the human need for it? Maslow’s original was called the “Theory of human motivation”. This is far more nuanced than the bastardised pyramid and includes discussion of exceptions. Importantly, needs are not organized in terms of importance, but are instead organised according to which needs will feel louder when unfulfilled.

As an example of this: “imminent starvation” is usually a stronger motivation than need to create art, but some people are willing to undergo deprivation for artistic purposes.

WHAT TO SAY INSTEAD

It’s not usually necessary to make a statement about what makes us human. So often when this comes up, it’s a very minor point made in support of a completely different point.

Unrequited love is one of the most universal and emotional experiences of all. Everyone past puberty has felt it, from time to time. Once I was pitching a teen story about a nuclear apocalypse. The person I was pitching to asked, “And who does the girl like that she can’t get?” I thought surely nuclear apocalypse would provide enough drama in her life, but it’ shard to really identify with that problem, whereas everyone can identify with unrequited love, so that will frequently be your way into a story.

Matt Bird, The Secrets of Character, p92, making an incorrect and wholly unnecessary sweeping statement which excludes many in the ace community. Not everyone past puberty has experienced unrequited love.

Corrected for inclusivity:

Unrequited love is an extremely emotional experience. Since most readers will have experienced this, it’s worth exploring in fiction…

(Frankly, until writing experts move away from expectations of amatonormativity, we’ll keep getting more of the same old, same old plots. No, not every story requires a romantic subplot.)

Often, when a “sex positive” (but not an asex positive) person says “we’re all sexual beings”, they are trying to convey the sense that there’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Below is another unnecessary tossed-off comment which could easily be nixed from an otherwise thought-provoking conversation about a broad range of contemporary feminist issues:

To control populations you need to control things like health, domestic life, deep control over the labour force, which means controlling population, which means controlling the individual at the level of their sexual behaviour. But we do also experience sex as deeply personal, individual and part of what makes us human, who we are. We need to think about how this is used against us, and to think about the possibilities of sexuality as something other than that. Rather than this thing that’s the intrinsic heart of the subject, the truth of who we are, if we could free it from that it could be something much more exciting.

Feminist Dr Sita Balani in conversation at the Novara FM podcast. Author of Deadly and Slick: Sexual Modernity and the Making of Race.

Better instead: Be genuinely sex positive and show by your words and actions that sex is nothing to be ashamed of. In the above example, it was entirely unnecessary to throw in a comment about how sex is ‘what makes us human’. The argument worked on its own.

AVOID DEHUMANISATION AT ALL COSTS

Outside a discussion among evolutionary biologists and similar specialists, it is almost impossible to non-problematically talk about ‘what makes humans human’ without dehumanising a group of very human humans.

Avoiding such statements isn’t simply a polite and inclusive strategy. This isn’t just about being nice. After all, genocide begins with dehumanisation.

RELATED TERM

ANTIHUMANISM

In social theory and philosophy, antihumanism or anti-humanism is a theory that is critical of traditional humanism, traditional ideas about humanity and the human condition. Central to antihumanism is the view that philosophical anthropology and its concepts of “human nature”, “man” or “humanity” should be rejected as historically relative, ideological or metaphysical.

Wikipedia, which cautions against confusing this term with misanthropy.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Gender Nihilism by Alyson Escalante (2015). Find it at The Anarchist Library. (Writes about antihumanism as it relates to gender.)

Radical Animism: Reading for the End of the World

Jemma Deer’s Radical Animism: Reading for the End of the World (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2020) invites the reader to take a moment and to ponder on the way of reading. In her book, the author challenges the narcissistic position of the human being: a status that has been established for some time and which has already been challenged before but does not seem to be changing quickly. The Anthropocene reveals the dangers which are connected to the human centrality and power; on the other hand, it requires new ways of engaging with the environment. These new ways are not limited to the gestures of consideration in relation to the profound changes that led to climate change in particular. They ask for a new mode of thinking when the inanimate is part and parcel of the human being. In this regard, Jemma Deer draws attention to reading and writing as ways and modes of engaging with the inanimate and with the environment that serves as a habitat for the acts of reading and writing. The book offers strategies for reading literary texts across cultures and times: the works by Shakespeare, Lewis Carroll, Virginia Woolf reveal new echoes in the context of the Anthropocene. Radical Animism is a gentle invitation to abandon human superiority and to explore the ways that subvert a conventional hierarchy of the human and the non-human.

New Books Network

Listen to this interview of James Gee, Regents’ Professor and Mary Lou Fulton Presidential Professor of Literacy Studies at Arizona State University. We talk about too much communication, about too much specialization, and about too much narrativization. We also talk about his books Introducing Discourse Analysis: From Grammar to Society (Routledge, 2018) and What Is a Human?: Language, Mind, and Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

James Gee : “It is absolutely crucial that the early-career researcher, that is, the person who is new to a field and also new to the community of that field — it is absolutely crucial that this researcher know the language of the group. In fact, I asked a biologist once — a very good one, by the way — I asked her, ‘How much biology do you need to know to be in your lab?’ And she said, ‘Not much. You just need to know the beginnings of the language. Then we will sit around a table and talk, and you will learn the language and you will learn biology.’”

New Books Network

BEHAVE: THE BIOLOGY OF HUMANS AT OUR BEST AND WORST

Cara is joined by famed neuroendocrinologist Dr. Robert Sapolsky, author of the new book “Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst.” They discuss the interplay between neurobiology, environment, development, and evolution in our decision-making processes, for better or worse. In seeking to understand why we do what we do, Dr. Sapolsky describes the very essence of what it means to be human.