When writers choose to tell a story via first person or deep third person narration, they frequently add depth to the character by conveying the idea that what happened isn’t necessarily the truth. Why? Because memory is imperfect. Today I’m taking a close look at examples of fictional narrators who know their memory may not be accurate.

WHY TELL THE READER ABOUT POSSIBLY FAULTY MEMORY?

- By admitting to readers that their memory may be wrong, they assure us (or attempt to trick us) into believing that the story is being told to the best of their ability.

- When events happened a long time ago (in retrospective narrative), it is only natural that memory leaves out some details while highlighting or conflating others.

- This blurring of events creates the word equivalent of shallow focus in photography, with some details crisp and clear, the rest blurred out, perhaps to the extent of creating a bokeh effect. This is the author managing which details (from many) are important to the story.

- A narrator who admits to possible memory lapses and failures generally comes across as reflective, emotionally mature

- and also quite detached from the self they were at the time of events, drawing a line between their intradiegetic self and their extradiegetic (narrating) self.

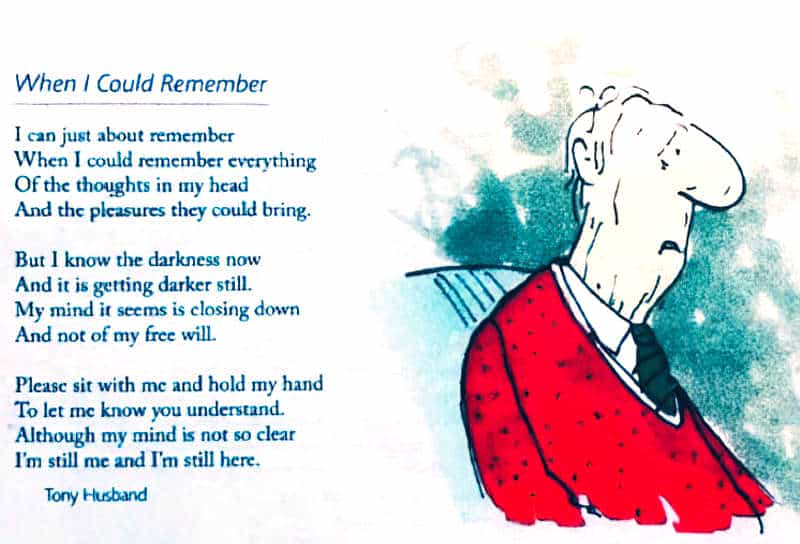

- A faulty memory may also indicate the dementia of old age

- or perhaps brain injury or trauma.

WE REMEMBER THE CONTENTS BUT NOT THE SOURCE

One of the most common types of faulty memory: We remember the contents of something we’ve heard, but we forget where we heard it from. This is how sometimes you find someone telling you a story that you know you already told them last month. This is why authors sometimes accidentally plagiarise. They forgot they read something written by someone else and truly believe it to have come from their own minds. This form of memory lapse is known as misattribution.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s butler narrator in Remains of the Day is an excellent example of a narrator who understands he may be misattributing dialogue:

“The evening before last I watched your father proceeding very slowly towards the dining room with his tray, and I am afraid I observed clearly a large drop on the end of his nose dangling over the soup bowls. I would not have thought such a style of waiting a great stimulant to appetite.”

But now that I think further about it, I am not sure Miss Kenton spoke quite so boldly that day. We did, of course, over the years of working closely together come to have some very frank exchanges, but the afternoon I am recalling was still early in our relationship and I cannot see even Miss Kenton having been so forward. I am not sure she could actually have gone so far as to say things like: “these errors may be trivial in themselves, but you must yourself realize their larger significance”. In fact, now that I come to think of it, I have a feeling it may have been Lord Darlington himself who made that particular remark to me that time he called me into his study some two months after that exchange with Miss Kenton outside the billiard room.

Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

Later in the book, in the telling of the story Mr Stevens acknowledges that things in his life seem far clearer in hindsight, though they are not at all clear at the time.

In thinking about this recently, it seems possible that the odd incident in the evening Miss Kenton came to my pantry uninvited may have marked a crucial turning point. Why it was she came to my pantry I cannot remember with certainty. I have a feeling she may have come bearing a vase of flowers ‘to brighten things up’, but then again, I may be getting confused with the time she attempted the same thing years earlier at the start of our acquaintanceship. I know for a fact she tried to introduce flowers to my pantry on at least three occasions over the years, but perhaps I am confused into believing this to have been what brought her that particular evening.

[…]

Naturally, when one looks back to such instances today, they may indeed take the appearance of being crucial, precious moments in one’s life; but of course, at the time, this was not the impression one had. Rather, it was as though one had available a never-ending number of days, months, years in which to sort out the vagaries of one’s relationship with Miss Kenton; an infinite number of further opportunities in which to remedy d the effect of this or that misunderstanding.

Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

Writers likewise talk about ‘turning points’ in regards to plotting, so there’s something metafictive about a narrator acknowledging there’s a distinction between the telling of a story and the living of it. The two can never entirely match up. Narrators can never be one hundred percent trusted, however truthful they may aim to be.

One memory in particular has preoccupied me all morning — or rather, a fragment of a memory, a moment that has for some reason remained with me vividly through the years. It is a recollection of standing alone in the back corridor before the closed door of Miss Kenton’s parlour; I was not actually facing the door, but standing with my person half turned towards it, transfixed by indecision as to whether or not I should knock; for at that moment, as I recall, I had been struck by the conviction that behind that very door, just a few yards from me, Miss Kenton was in fact crying. As I say, this memory has remained firmly embedded in my mind, as has the memory of the peculiar sensation I felt rising within me as I stood there like that. However, I am not at all certain now as to the actual circumstances which had led me to be standing thus in the back corridor. It occurs to me that elsewhere in attempting to gather such recollections, I may well have asserted that this memory derived from the minutes immediately after Miss Kenton’s receiving news of her aunt’s death; that is to say, the occasion when, having left her to be alone with her grief, I realized out in the corridor that I had not offered her my condolences. But now, having thought further, I believe I may have been a little confused about this matter; that in fact this fragment of memory derives from events that took place on an evening at least a few months after the death of Miss Kenton’s aunt — the evening, in fact, when the young Mr Cardinal turned up at Darlington Hall rather unexpectedly.

Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

Mr Stevens, the first person narrator, then goes on to write down the events which follow regarding Mr Cardinal’s visit and by the time he has finished writing he is sure that the two instances of Miss Kenton crying are separate incidents.

This tells the reader that there were numerous instances of Miss Kenton crying, but that at the time she worked with Mr Stevens, Mr Stevens hardly noticed their frequency. He has become reflective only in the slowing-down of old age.

At the end of the book, Mr Stevens confesses to a stranger on the pier that he fears he is starting to make mistakes in his work, and laments that he gave his very best to Lord Darlington. The reader might then deduce that Mr Stevens’ memories conflate partly due to time passing, partly due to increasing old age.

Another form of misattribution in memory: believing that you have seen or heard something you haven’t.

Prominent researchers in this area include Henry L. Roediger III, PhD, and Kathleen McDermott, PhD. An illustration of it, said Schacter, is the rental shop mechanic who thought that an accomplice, known as “John Doe No. 2,” had worked with Timothy McVeigh in the Oklahoma City bombing; he thought he’d seen the two of them together in his shop. In fact, the mechanic had encountered John Doe No. 2 alone on a different day.

The seven sins of memory: Convention award-winner Daniel Schacter explained the ways that memory tricks us, the American Psychological Association

High profile crime cases cause issues for police detectives, as members of the public can conflate news stories with personal experience.

Another example: numerous women believe they were almost abducted by serial killer Ted Bundy, but managed to get away. One of those people is singer Cyndi Lauper, who jumped from a moving car in 1972 after being picked up at 3am in New York. I have no idea whether this really happened or not, but police believe Bundy was nowhere near New York at this time. They put Lauper’s story down to a failure of memory. It is perhaps the case that the incident happened, but that the man was not Bundy. This would be another example of misattribution.

MEMORY IS TRANSIENT

Basically, transience refers to the decreasing accessibility of memory over time. This is a natural feature of ageing (or of time passing).

CASE STUDY: BREAKING BAD

In Breaking Bad Season One, Walter White sits with Krazy-8 in the basement, for a time conflicted about whether to kill him or not. Walter learns that Krazy-8’s family own the furniture store where Walt and Skyler have made purchases before. Walt misremembers that he purchased Walt Junior’s bassinette there. Krazy-8 corrects him: “That’s a specialist item.” Walter then recalls that it would have been the cot they purchased there, not the bassinette.

The distinction between bassinette and cot is not important to the plot. Nor is it relevant to the metaphorical of the layer. Instead, this scene lends realism. We’ve all purchased furniture. We’ve all forgotten exactly which furniture was purchased where. Transience of memory is relatable. But few of us have held a local druglord captive in a basement debating whether it’s morally okay to kill him or not.

By the way, I suspect the writing of that Breaking Bad scene was influenced by the actor who plays Hank Schrader. Dean Norris could have brought that extra layer of realism to the script because his father Jack owned a furniture store.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN PAST AND FUTURE

Dementia, brain injury or drug use can illuminate the transience of memory in all of us. According to new research, our ability to remember the past is directly related to our ability to imagine a future:

[In order to converse] we have to know each other, we have to know our personal pasts. And we have to exercise our imagination regarding our futures. All of these come together when we talk to each other. Without memory our conversations would be oriented around the present because we can’t interrogate our past. But paradoxically, we can’t really have conversations about the future because memory allows us to imagine the future.

We know this because people who have damage to the parts of the brain concerned with memory suffer deficits in imagining. So if you ask them, “What are you thinking at this moment?” they’ll tell you and they’ll do this with great ease. Ask them about what they did last week — can’t really remember. Ask them what they’re going to be doing next week, or the week after next, and they’ll say, “Hmm. Pretty much what I’m doing now.” They can’t imagine alternative futures. We need memory in order to imagine different futures. This has only really become understood probably in the last ten years or so.

The Future of Talking: A Discussion with Shane O’Mara at New Books Network

This reality should affect how authors write characters with memory loss. Where authors attempt to get inside the heads of characters with dementia and memory related brain damage, viewpoint is now limited to the present with flashes of insight from the past melding with the present in disconnected ways. The future is wholly unavailable unless pushing out of viewpoint.

An excellent film which explores the confusion and terror of dementia is The Father starring Anthony Hopkins.

BLOCKING

Blocking refers to the temporary inaccessibility of stored information, e.g. “tip-of-the-tongue syndrome”.

THE FREUDIAN SLIP IN COMEDY

The Freudian slip is another related kind of ‘temporary forgetting’, sometimes deployed by speakers on purpose to say something risque while signalling they know it’s not an acceptable thing to say. (This category of joke is a type of paralepsis.)

Before Freud introduced the masses to the so-called “Freudian slip”, ancient authors were making use of the phenomenon in their works.

One example comes from Roman comedian Plautus, who used the device in Casina. His lusty old man character betrays via Freudian slips that he has a “secret” desire to wed Casina himself. In other plays, Plautus frequently has his characters come out with, “That’s not what I meant to say.”

For more on that, see Freudian Slips in Plautus: Two Case Studies by Michael Fontaine (2007)