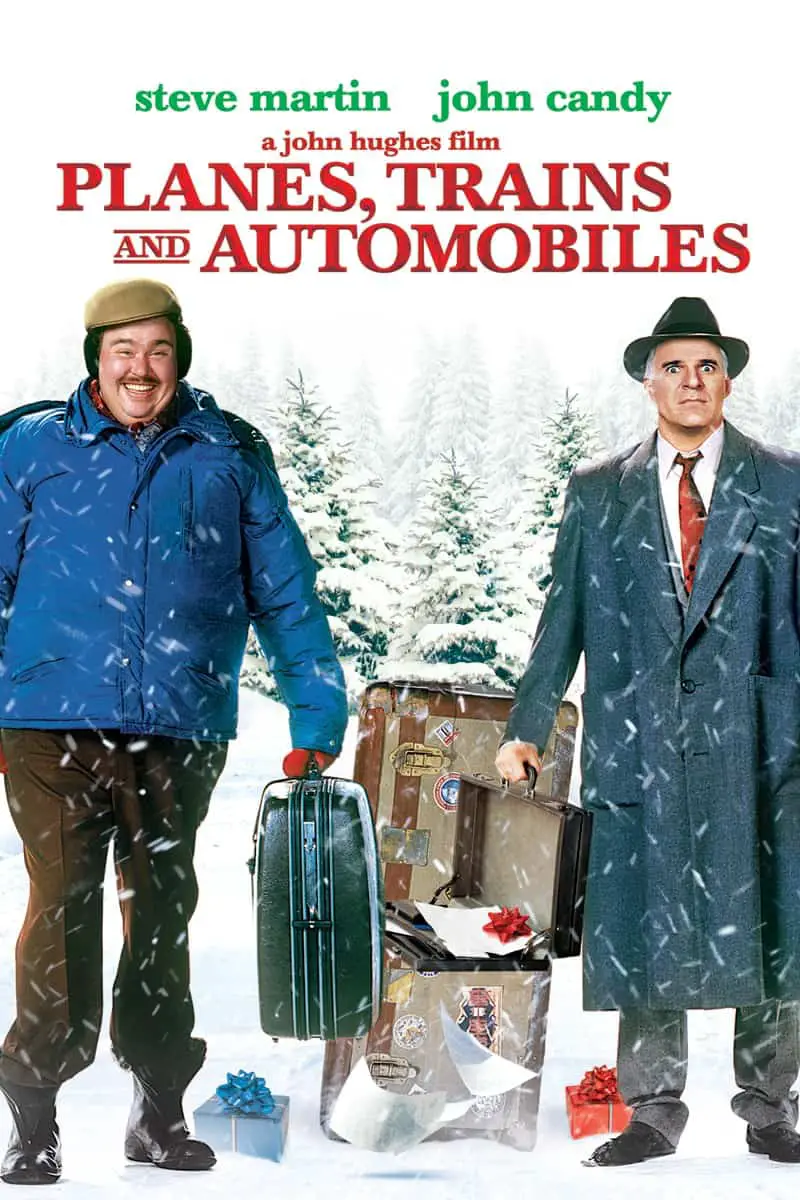

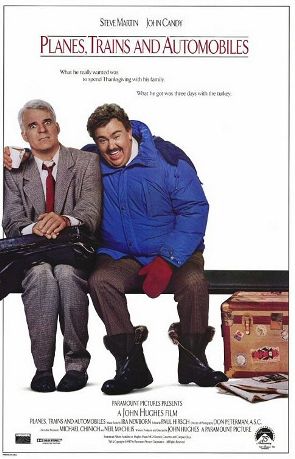

Planes, Trains & Automobiles is a thanksgiving comedy from 1987. The film has been given an R rating — not, as I expected, because of the pillow scene, but because of the cussy airport scene.

[Hughes] is not often cited for greatness, although some of his titles, like “The Breakfast Club,” “Weird Science,” “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” and “Home Alone,” have fervent admirers. What can be said for him is that he usually produces a real story about people he has clear ideas about; his many teenage comedies, for example, are miles more inventive than [more] recent sex-and-prom sagas.

Roger Ebert

Planes, Trains and Automobiles is a very much a movie of the 80s, and the reuniting scene at the end with the tearful wife is a bit eye-rolly to me, but the comedy is still relevant today: If anything, more of us are travelling more often and can relate well to travel delays next to annoying co-passengers.

Good stories don’t need to be complex. E.T. is another example of a film which has a simple story line but which was very popular in the 1980s.

The movies that last, the ones we return to, don’t always have lofty themes or Byzantine complexities. Sometimes they last because they are arrows straight to the heart.

Roger Ebert

Planes, Trains and Automobiles probably works because the holiday itself is not the main action. Instead, we see a man who learns the ‘true meaning of Thanksgiving’. The holiday itself is simply the ticking-clock.

Ticking clocks are often used in other genres such as thrillers and action movies, but the device is also used (less commonly) in comedy journey stories.

‘TRAPPED!’

Public transport is the ideal setting for a narrative because when you’ve got a main character and a main opponent, you have to find a way, as writer, to force them together into the same space. Howard Suber, in The Power of Film, wrote that almost every popular film could be justifiably called Trapped. In Planes, Trains and Automobiles we have a well-off white guy, who is basically living The American Dream, except he is trapped first in his workplace as his boss hems and haws in a board meeting, then we see him trapped in a variety of locations as his transportation continues to let him down.

Sentence Behind The Story: A man learns the true meaning of Thanksgiving when he is forced into the company of a man much less fortunate than he is on Thanksgiving Day one year.

Theme Thread: When you are blessed with good fortune and family you must show charity for those who don’t have what you have.

Setting: A large distance across America, juxtaposed with cramped and unpleasant transportation.

Symbol Thread: The lucky versus the unlucky

SYMBOLISM IN PLANES TRAINS AND AUTOMOBILES

Story Level Symbolism

Christians will recognise that this is a Christian story (insofar as Christians sometimes like to think that being charitable is a specifically Christian thing):

One is reminded of the reluctant Simon helping Jesus carry his cross.

The Imaginative Conservative

See also The Stations Of The Cross, which is a series of pictures often seen decorating Catholic churches. There a few different versions of these steps, and only some are described in scripture. The pictures depict the events on the day of the crucifixion, and as you may notice, there are a few commonalities between this and the 22-Steps of your typical movie:

- Jesus is condemned to death (INCITING INCIDENT — SOMETHING TERRIBLE HAPPENS TO THE HERO)

- Jesus carries his cross

- Jesus falls the first time (FIRST REVELATION AND DECISION)

- Jesus meets his mother (PLAN)

- Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross (HERO MEETS AN ALLY)

- Veronica wipes the face of Jesus (ALLY)

- Jesus falls the second time (SECOND REVELATION AND DECISION)

- Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem (CHANGED DRIVE AND MOTIVE — IF HE CAN’T SAVE HIMSELF HE CAN TELL BARREN WOMEN TO BE HAPPY ABOUT IT)

- Jesus falls the third time (THIRD REVELATION AND DECISION)

- Jesus is stripped of his garments (ATTACK BY OPPONENT)

- Crucifixion: Jesus is nailed to the cross (GATE, GAUNTLET)

- Jesus dies on the cross (VISIT TO DEATH)

- Jesus is taken down from the cross (Deposition or Lamentation)

- Jesus is laid in the tomb. (NEW SITUATION)

Object Symbolism

“Refer and repeat.” The trunk is the main symbol in this film and we see it again and again, as explained over at ScreenPrism:

The trunk is an iconic prop piece from the film, and during the picture serves as the catalyst for a number of jokes. Before the characters of Neal (Steve Martin) and Del even meet, Neal trips over the trunk on the sidewalk while hailing a cab. It’s the first of many trunk-related blunders to come. In the spirit of a Thanksgiving film that doesn’t ignore its holiday associations, the trunk serves as a shared burden and a symbol of budding kindness between the men.

The trunk also becomes a point of mystery as the film moves forward. What exactly is in this thing? We see Del remove a hypoallergenic pillow and a photo of his wife, but what demands the rest of the space within such a large object is never seen. It serves as a nice symbol of a salesman’s life on the road — in one scene Del says he “hasn’t been home in years.” He claims he’s speaking metaphorically, and the inference is that most of his worldly possessions are within the box he transports across the map.

ScreenPrism

“Prelude” by Katherine Mansfield is a completely different kind of story — different era, different place, different form. But Neal and Kezia share in common the feeling of being trapped, which in both stories is symbolised by a container. For Neal it is Del’s annoying trunk; for Kezia it is a wide array of containers — the pill box, the match box and so on.

CHARACTERISATION IN PLANES TRAINS AND AUTOMOBILES

In order for stock characters to be relatable, writers have to ‘transcend stock’.

ImaginativeConserative explain how John Hughes managed to transcend the stock characters of a cynical New York City ad-man and a boorish traveling salesman:

Key to the success of the film is this refusal of writer-director Hughes to make cardboard characters out of Griffith and Page. The shower-curtain-ring salesman, despite his boorishness, is aware that he is a “blabbermouth” who can annoy others. [Neal] Page is also not one-dimensional. He is an everyman in his understandable desire to avoid the loquacious and overbearing [Del] Griffith, yet his face shows the regret he feels when he realizes he has deeply wounded Griffith in the hotel room scene described above.

This is essentially an ‘odd couple’ film, because Neal and Del could hardly be more different.

STORY STRUCTURE OF PLANES TRAINS AND AUTOMOBILES

As Roger Ebert said, this film is ‘soundly constructed’.

Although Neal is clearly the hero, changing the most throughout the story (from entitled cynic to grateful, more positive guy), it is John Candy’s character, Del, who has the interesting ‘ghost‘ (a troublesome part of one’s backstory). Sure enough, the nature of this ghost is fed to the audience gradually via hints, and as is usual for ghosts, the audience finds out what that ghost is about 3/4 of the way through the story. The audience realises there’s something fishy about Del’s so-called perfect life before Neal does. Neal will discover the truth at the ‘anagnorisis’ stage.

Neal’s anagnorisis is shown via Del. Del is the sort of guy who would talk to himself out loud (actually to his dead wife, Marie), so we are shown Del’s transformation as it happens. (Simultaneously with Neal’s, inside the motel he will later share with Del.) John Hughes was not afraid of being ham-fisted. (Comedy seems to be one genre in which we forgive tricks like melodramatic monologues and the over-the-top insights into Neal’s thoughts — via unabashed cuts and flashbacks.

Anagnorisis: By the end of the story Neal Page will be a lot more tolerant.

What he believes about himself at the start: At the start he feels entitled. He has the perfect life in the suburbs with a wife and family. He can afford to travel home first class. Del calls him a ‘cold-hearted cynic’ in the hotel room, putting into words what the audience has already noticed about Neal.

Need: Neal needs to become warmer and less cynical. By the end of the film he will have become more like Del, but not all of his transformation is good. Del is also a little sneaky (using Neal’s credit card, for instance), and Neal, too, chooses to forget he can’t pay for any of the little drinks he took from the bar fridge.

Neal desire is to make it home by 9pm for Thanksgiving. The stakes are upped when we see a cut to his daughter’s Thanksgiving pageant in which she says thank you for her dad coming home.

Del Griffith has the significant ghost – his wife is dead and he is homeless. (I wonder how he ended up homeless. With healthcare the way it is in America, perhaps he re-mortgaged the house to pay for his wife’s medical treatment?)

We are offered hints all the way through, which probably won’t be fully assimilated upon initial viewing. For instance, that huge trunk Del has been dragging around New York.

At first we think he’s just one of those annoying passengers who can’t pack sensibly, or perhaps the trunk is full of curtain rings. He carries his own pillow due to ‘allergies’, but in fact he carries all of his worldly goods with him, and this would include a pillow. His pillow is the extent of his home. Washing his socks in the sink shows that he has come up with a variety of hacks for living on the road; Neal has the luxury of taking his home to be washed by his wife (no doubt).

Setting of Planes, Trains and Automobiles

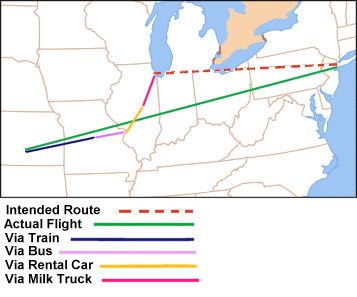

First of all, this story would not work if set in, say, Japan.

America, across large distances, from NY to Wichita to Chicago. When Neal’s flight gets rerouted to Wichita this is funny because it’s pretty much as far away as you can get from Chicago while not actually leaving the country.

But within that vast space there are a number of very small spaces which feel claustrophobic – a plane, a train, and a succession of automobiles. This throws the everyman character and his opponent together.

Neal’s unpleasant setting Neal provides contrast against the peacefulness of his warm, cosy home where his wife is waiting for him with his children. We see how out-of-place Neal is in contrast with Del, who has friends all over the place and can better gauge the appropriate song to sing on the bus.

We are shown nothing about Del. We need to be shown how high the stakes are for Neal, though. Here is the real house filmed in Planes, Trains and Automobiles. It’s a ‘classic colonial’ of the sort I used to think could be found everywhere in America when I was a kid in New Zealand, seeing America only via TV. In movie land, this is the house that denotes success; a family house. You need a good job to live in a beautiful house like this one.

Neal waits for a cab in NYC, as just one of many people just like him, we are shown.

Shortcoming & Need (Problem)

Psychological Need: He has no patience for things that don’t go to plan.

Moral Need: He is a little rude to the flight attendant when he is bumped down to cattle class, but the audience can still empathise with him because he really is having a shitty time.

Inciting Incident

The flight to Chicago gets rerouted to Wichita, where Neal and Del are stuck in bad weather. There are no available rooms by the time Neal has finished calling his wife. So Del and Neal end up in the same bed in the same motel room.

Desire

Del wants only to please. Neal wants only to be left alone.

Roger Ebert

Neal only wants to get home in time for Thanksgiving. Since Thanksgiving with family is an important event for Americans (and anyone outside America can relate to our own special family events), the holiday provides a great ‘ticking-clock’ to the story. The stakes are high and time is running out. Thanksgiving is, of course, about giving thanks, which is the very thing Neal is unable to do. He will actually learn, this year, to be grateful for what he has. So this film supports the philosophy of this holiday rather than challenging it (as some films challenge the meaning of Christmas, for instance).

Ally/Allies

Neal is alone on this trip – Del is an opponent psychologically, though in practical terms he tries to be an ally, offering to share his room, for instance, and finally saving Del by hitching them a ride on a truck, which Neal couldn’t have managed on his own due to being generally unpleasant to people when he’s pissed off. Del is not the company Neal wants, but he’s the company Neal needs, because from Del he’s going to learn to be a nicer person.

Opponent

Apart from Del, the people Neal meets along the road are unhelpful at best and antagonistic at worst, because Neal is the kind of guy who rubs service workers up the wrong way.

Del is a twist on the ‘fake-ally opponent’ in that he is a stumbling block for Neal, but he does have genuinely good intentions. I would call him an ‘ally-opponent’.

Changed desire and motive

Neal’s basic desire (to get home for Thanksgiving) stays the same throughout the story. (A ‘single desire line’, as per the story rules — new desire = new story.) His desire morphs only in that he changes his mode of transportation every time his vehicle breaks down. Can’t take the plane? Take the train. Can’t take the train? Okay, take the bus. Can’t take the bus? Okay, rent a car. Rental car’s not there? Go back to the rental company desk and order a replacement. You threw your papers away in a rage and abuse the woman behind the desk? No problem, hire a taxi. Taxi driver punches you in the balls?

Hitch a ride with the annoying Del. Del’s car burns to a crisp and a police officer orders you to get it off the road? Hitch back to Chicago in the back of a frozen goods truck.

First revelation and decision

There are a number of minor revelations along the way, or red-herrings. For example, Neal’s $700 is stolen at the dodgy hotel by an intruder. Neal thinks it’s Del. (This has been foreshadowed by Del going into his stuff.) But they work out they’ve both been robbed, which restores Neal’s faith a little. Neal can’t fly home because the flights are booked out. So they decide to take the train. But the train breaks down.

Notice the placement of the ornamental fighting animal in the background. (Behind Neal rather than behind Del.) This scene foreshadows the later one, in which Del really is forced to use Neal’s credit card.

Plan

Neal plans to take a cab to Jefferson City.

Opponent’s plan and main counterattack

Del’s plan is to stay with Neal because he likes him (and also probably because he has no money whatsoever) so he hooks up with Neal again and again. Being friendly is what works for Del most of the time, and he can’t quite understand at first why Neal wouldn’t like him also.

Drive

At no point in the story does Neal decide just to give up and spend Thanksgiving wherever he is stuck. At one point he even says, “There’s no way I’m spending Thanksgiving in Wichita”. Everything that happens to him makes him more determined than ever to get home.

Attack by ally

Neal is the opponent and ally rolled into one. They have a series of arguments over the course of the film, all of which lead to Neal’s character change. “Well, there are things I don’t like about you, too,” Del says, after Neal complains about his foot odour in the car. He doesn’t want to say anything really personal, though, because he’s not that kind of guy, so he says, “You’re always playing with your balls.” The thing Neal is learning here is how not to fight dirty. We’ve already seen him in action, in which he attacks Del in the most personal way.

Audience revelation

Cafe lunch scene: The audience can see around this point that Del is homeless. He lets it slip over the lunch that he insists on paying for. Neal queries him on it and he takes it back, saying it’s a ‘figure of speech’ that he hasn’t been home in years. Neal brushes it off but the audience remembers it.

Gate, gauntlet, visit to death

When Neal is rude to the rental car woman she decides not to help him out with another car. A taxi driver outside won’t help him either. He punches Neal in the balls when he’s down on the ground. A cop passes by which saves him from worse.

But he comes even closer to death when Del gets his jacket stuck on the car seat knob while he’s driving. He doesn’t want to wake Neal up because they’ve just had an argument, so he tries to get himself untangled to disastrous consequences. He drives back onto the highway after spinning off the road, but is going in the wrong direction.

After narrowly avoiding two trucks the car catches fire. They’re now stranded in the middle of the highway. Neal’s wallet is in the glove box. His credit cards are burnt to a crisp.

Battle

It emerges that Del has used Neal’s credit card to pay for the wrecked rental car. They have a huge argument about Del using it. Neal is sure that Del has stolen it. The audience knows that the switch up was an honest mistake. There is a literal fight: Neal punches Del in the guts.

First Moral decision

The two of them make their way to a motel where Neal gets to feel what it’s like to be penniless and homeless, because all he has are credit cards that have been burnt to a crisp. He pays with $17 and a watch that is worth a helluva lot more. Del, meanwhile, only has $2 and a (cheap) Casio watch. Neal is Neal’s room is a twin, so after realising how it feels to be poor he lets Del share the room. This is the beginning of his charity towards the less fortunate.

Neal and Del’s Anagnorisis

While he’s deciding to be charitable, in the burnt out car with no roof and the snow fluttering down, Del has his own revelation: Marie, you’re right. I meet someone I really like and I go overboard. I smother the guy. When am I gonna wake up? (Talking to himself, because he’s the sort of character who would talk to himself.) Each of them has a simultaneous revelation, as it turns out.

Del drives the burnt out car for a while, until they’re pulled over by a cop.

After another ride in the back of a frozen goods truck, also set up by the personable Del, who seems to be able to talk his way into anything (except when it comes to Neal), they end up in Chicago. Neal has now learned some gratitude.

“You got me home. A little wiser, too.”

Apparent defeat

By the time they two are in the back of the truck and it’s already the day of Thanksgiving, we all might wonder what else is going to go wrong. Neal has been basically wordless and morose, letting Del lead him home, obviously resigned to fate.

Second Moral Decision

The last scenes of the movie carry the emotional payoff we have been half-awaiting all along. For Neal, they reflect a kind of moral rebirth such as Scrooge experiences in another great holiday tale: He has learned his lesson, and will no longer judge people by their appearances, or by his own selfish standards. There is true poignancy in the scene where Neal finds Del waiting alone on the L platform.

Roger Ebert

This more minor moral decision from earlier precedes this main one: Del’s wife is dead and he is homeless. Neal realises this when he’s on the train back in Chicago almost home and has time to reflect. We are shown what he is thinking – his children, pie coming out of the oven, a turkey, then he thinks of all the times with Del we’ve been shown Del has no wife. He rushes back to the station where he finds Del alone. Del admits that Marie’s been dead for eight years.

New situation

Del has learnt not to be so clingy with people he’s just met, and Neal has learnt to call Del ‘one unique individual’. (“Is that Latin for asshole?”) He’s learnt to take life as it comes.

Together Neal and Del carry the huge trunk down the road leading to Neal’s massive house. This is a visual symbol of their equality as human beings and as friends.

“Boy, you are one lucky guy, Neal. I won’t stay long, maybe I’ll just come in and say hi and then I’ll be on my way, all right?”

We know that even if Del leaves straight after Thanksgiving and the two men never see each other again, Neal’s relationship with his wife has now changed for the better (I hate to think how they argued before), and he will be forever a more grateful man who can roll with life’s transportation punches.

FURTHER WATCHING

Notice how Neal (Steve Martin) initially dislikes Del (John Candy), and considers him an obstacle to be overcome, or at least a pain in the ass. Then, as they are forced to work together to achieve their common goal, Neal eventually grows to like Del, benefit from their friendship, and in the end, generously give him something in return.

This same dynamic occurs in The Heat, Midnight Run, Lethal Weapon, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (plus numerous other Shane Black screenplays), Toy Story, The Guard, Rush Hour, Hot Fuzz, Central Intelligence and an abundance of other comedies and action films.

Michael Hauge